Argumentation Strategies of the Early Childhood Language in the

Gender Perspective

Siti Salamah

1

, Fathiaty Murtadho

2

, Emzir

2

1

Student of Doctoral Program in Applied Linguistics Department, State University of Jakarta, Indonesia

2

Department of Applied Linguistics, State University of Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Argumentation, Gender, Types of Argumentation, Pragmatic Strategy

Abstract: The way children view the world is a process of thinking critically that reflected through language expressions

that can be seen from pragmatic strategy in giving argumentation. To date, the study on child’s language in

Indonesian is only focused on the form and structure of argumentative sentences. Meanwhile, the study that

is focused on child’s language viewed from gender perspective has not yet been conducted significantly,

especially that is related to the argumentation strategy. Hence, the study of this paper will be focused on

child’s pragmatic strategy reviewed from gender perspective. The subject and object of this study covered the

use of sentence on children aged 5-6 years old. The study applied descriptive qualitative method. The data

were collected using participated and non-participated observation methods. The data then were analyzed

using the pragmatic match method. The result of this study shows that there were some differences between

the boys and girls reviewed from the frequency intensity of the uttered argumentation types and the pragmatic

strategy in expressing intention. The girls had better abilities in qualitative and comparison-typed

argumentations. On the other hand, the boys were better in analogy-typed argumentations. Either the boys or

girls had equal ability in argumentations type quantity and expert opinion. In the use of pragmatic strategy,

the boys used more representative strategy than the girls. In contrast, the girls were skilled in arguing using

control, expressive, and social strategies than the boys.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human always think critically in deciding their life

perspectives. The ability to think critically can be

traced during child phase. Children have their own

world and the way children view the world is a

process of critical thinking that expressed in their own

uttered languages. Riley and Reedy (2005) confirm

that children decide their positions and are

collaboratively connected with their surroundings

through expressing ideas. Children always express

something, either when they are playing, studying, or

interacting with their family. Those speech acts (at

least are potential to) play role in the process of

emerging opinion differences (Van Eemeren &

Grootendorst, 2003). This is because every child has

different experience schemes in capturing the world,

one from another. Children start developing verbal

utterance for different purposes and functions.

Utterance that emerges opinion differences is the

form of argumentation. Dowden (2011) states that

argumentation refers to the conclusion of more than

one statement utterance. Child’s argumentation

utterance is reflected in the use of pragmatic strategy

in daily utterance, either when asking questions,

expressing opinions, stating explanations, showing

expressions, and asking someone else to do what their

wants. The argumentation uttered by children is

classified into some types; which are quality type,

quantity type, comparison type for consistency,

expert opinion, analogy, and other types (Bova and

Arcidiacono, 2014). The description of

argumentation type is explained as follows:

(1) Quality-typed argument is an argumentation

viewed from quality aspect of something, for

instance good/bad, light/heavy, and etcetera.

(2) Quantity type refers to the argumentation viewed

from the quantity aspect.

(3) Comparison type for consistency is the

argumentation that refers to the behavior of past

utterance. This type of argumentation holds on to

Salamah, S., Murtadho, F. and Emzir, .

Argumentation Strategies of the Early Childhood Language in the Gender Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0009001304470455

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education, Language and Society (ICELS 2019), pages 447-455

ISBN: 978-989-758-405-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

447

the principle of “affirmation of something in the

past explicitly or implicitly is necessary to be

maintained now.”

(4) Type of expert opinion is defined as the

argumentation that refers to the opinion that has

authority. In this issue, authority can be referred

to the experts or adults who are considered have

further knowledge by children.

(5) Analogy type is the argumentation that refers to

the comparison of two equal things at major

premise when minor premise appears then the

conclusion is taken by referring to major premise

with the following illustration:

Major Premise: Generally, Case C1 is similar to

case C2. Minor Premise: Proposition A is true (false)

in Case C1. Conclusion: Proposition A is true (false)

in case C2.

The pragmatic strategy itself is the way children

deliver their utterance meaning. Next, Owen (2012)

confirms that illocution act has appearance sequence

of intentions that is meant to be delivered. Lakoff (in

Eckert and Ginnet, 2003) argues that the difference of

children argumentation strategy from pragmatic

aspect can be viewed from the aspects of question

mark (pemarkah tanya), sign of certainty/doubt,

reinforcement word, indirect form, meaning-reducing

mark (pemarkah pengecil makna), euphuism, and

politeness. Coates (2013) states that the pragmatic

strategy itself involves responding way, certainty

mark (penanda kepastian), question mark (pemarkah

tanya), question, instruction and direction, swearing

way, taboo language, and praise. While according to

Musfiroh (2017), the type of argumentation strategy

is based on its pragmatic function category, which is

in the form of control, representative, expressive,

social, tutorial, and procedural as depicted in table 1.

Table 1: Illocution Functions Used by Children

No.

Category of

Pragmatic

Function

Initial

Speech Act

Preferred

Intention

1.

Control

Asking the

interlocutor to

do something

Asking

something

Instructing

Protesting/

opposing

Protesting

2.

Representative

Asking

answer

Asking content

Giving name

Giving name

Statement

Answering

Answering

Responding

question

Explaining

Explaining

3.

Expressive

Showing anger

Expressing

attitude and

feeling

Saying

exhaustion

4.

Social

Greeting

Greeting

Saying

good bye

5.

Tutorial

Repeating/

practicing

Repeating/

practicing

6.

Procedural

Calling

Calling

In gender perspective, mindset and way of arguing

between man and woman have differences that can be

traced from early years. According to Hellinger and

Buβmann (2003), the study of language difference

between boy and girl is directed to the understanding

about how gender ideas are interpreted to the way of

perception and universal construction toward gender

in language unit by linguistic, social, and culture

parameters. Rowland (2014) confirms that girls

collect language faster than boys. In western

countries which tend to be industrialist, the girl gets

mature faster in language cognitive process. On the

other hand, language socialization process of

something can also affect child’s language ability. It

influences the difference of interaction topic. Parents

tend to talk more about a particular topic to boy or

girl. It shows that boy tends to dominate words related

to transportation than girl does.

Speech of argument has difference gradation in

boy and girl language, especially the used strategy.

Haslett (1983) confirms that girls develop strategy at

first time, are politer and complex at the use of

pragmatic strategy in daily conversation. This issue is

strengthened with a study result by Ladegaard (2017)

in Denmark that shows the girls are politer compared

to the boys. It is marked with the use frequency of

Danish politeness marker with 53% of the girls and

47% of the boys. Clark (2012) states that in a role play

study, the boys and girls were asked to persuade their

mothers to let them play or buy them toys. In the study

scenario, the mothers were directed to refuse for five

times. The results of the study showed that the girls

tended to practice a strategy in adjusting their

language in giving arguments with the norms and

meaning about fairness than the boys. The study

conducted by Wade and Smart (via Morrow, 2006)

shows that in searching for support when talking with

friends, the girls emphasized more on the problems,

while the boys emphasized more on the importance

of friend for diversion and activity. Therefore, early

childhood, either the boys or girls, are capable to start

strategizing in giving arguments.

ICELS 2019 - International Conference on Education, Language, and Society

448

The study on child argumentative utterance in

Indonesian is often merely focused on the sentence

form and structure. Meanwhile, the study focusing on

the argumentation pragmatic strategy of child

reviewed from the gender perspective has not yet

conducted significantly. This study will discuss how

the argument of the boys and girls in their daily life,

either from the aspect of type of argumentation or the

aspect of applied argumentation strategy.

2 METHODS

This study implemented qualitative descriptive

method. In this study, 20 children aged 5-6 years old

(8 boys and 12 girls) were involved as participants.

The object of this study covered argumentative

utterance in Indonesian, which uttered by the

participants. Mukherji (2015) confirms that to

descriptively study early childhood participants, the

data would be suitably collected through observation

method, either participatory or non-participatory. The

data of this study were collected through both

participatory and non-participatory observation

methods. Then, the data were noted down and

analyzed pragmatically. Merriam (2009) declares that

qualitative study must describe the data from the field

as it is. The data that have been noted down and

analyzed then were presented descriptively in the

form of narrative extracts and strengthened by simple

diagram to show the frequency of data appearance.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1 Types of Argumentation

Argumentative sentence is often uttered in some

conversations when children are interacting in their

surroundings. The form of argumentative sentence

depends on the conversation topic chosen by children

and their interlocutors. Child’s argumentation topic

can be reviewed from either internal or external

aspects. The internal topic involves an idea about

oneself that is divided into a number of categories

such as physical, characteristic, and behavior. The

external topic focuses on the conversation related to

other than the child’s self, such as parents, play pals,

neighborhood, schools, hobbies, games, and

activities. The external topics covers the categories of

physical, characteristic, behavior, similarities, and

differences. From each topic talked in child’s

utterance, arguments appeared in various types. The

types of argument put forward by the children in this

study were the type of quality, type of quantity, type

of comparison, type of expert opinion, and type of

analogy.

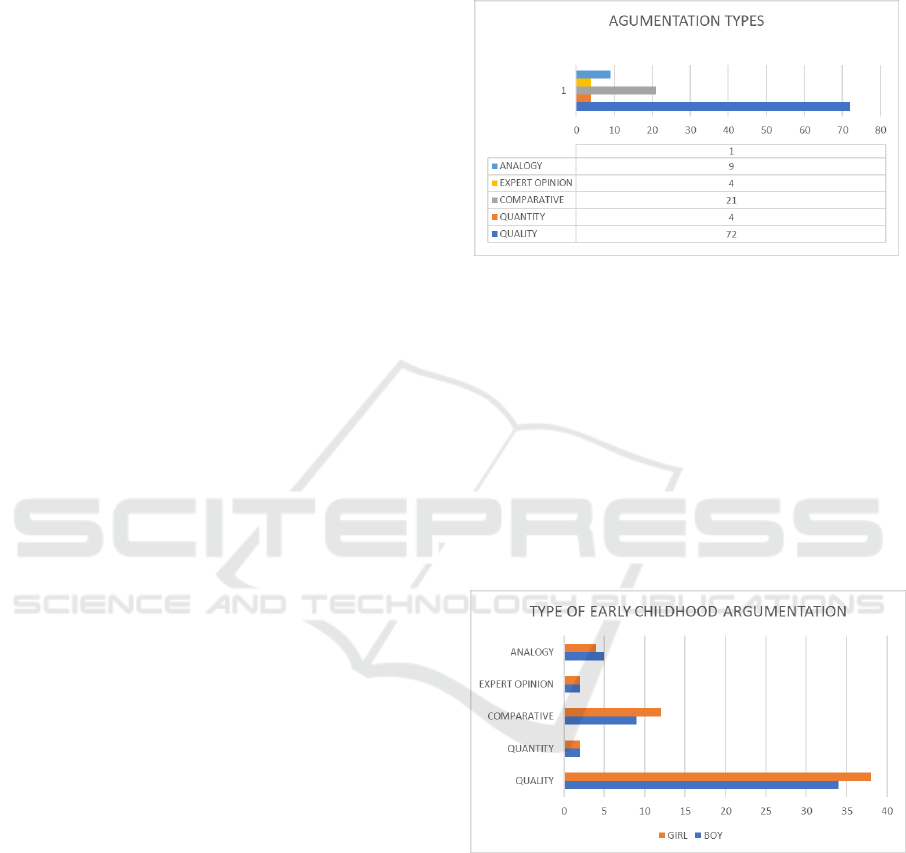

Diagram 1: Distribution of Types of Argumentation on

Early Childhood

The most stated type of argumentation is the quality

argument. Then, the second position stated type of

argumentation by the child’s is the comparative

argument. The last position, there are analogy

argument and expert opinion argument.

The interesting thing is that if it is reviewed from

the gender aspect of the early childhood, the

argumentation intensity between the boys and girls

will be clearly seen. The difference of argumentation

use in each type can be viewed on the following

diagrams.

Diagram 2: Distribution of Types of Argumentation based

on Gender

Diagram 2 shows that the girls outperform the boys

in types of quality and comparison argumentations.

Meanwhile, the boys outperform the girls in terms of

analogy argumentation. On the other hand, the boys

and the girls have equal ability in types of expert

opinion and quantity argumentation types.

Argumentation Strategies of the Early Childhood Language in the Gender Perspective

449

3.2 Strategy of Argumentation

When communicating, children are able to perform

several argumentation strategies such as

representative, control, expressive, and social. This

statement is pictured in diagram 3, which is related to

the distribution of strategies used in each type of

argument.

Diagram 3: Pragmatic Strategy of Each Argumentation

Type

The results of the study as shown in diagram 3

indicate that the most used strategy of argumentation

is the representative strategy. The second most used

strategy is the control strategy. Children are able to

express their intentions so that the interlocutors

follow what they want. The control strategy is

performed through commanding, protesting,or

opposing with prohibition. The expressive and social

strategies are already acknowledged and applied to

the interlocutors. Early childhood is already able to

show expressions to communicate their intentions.

They also have known the way of making friends

using social strategy. The boys applied the

representative strategy more than the girls. In

contrast, the girls were more competent in arguing

using control, expressive, and social strategies than

the boys.

The description of strategy in each type of

argument will be explained as follows.

3.2.1 Strategy of Quality Argumentation

In uttering quality-typed argument, the boys and girls

performed four strategies, namely control strategy,

representative strategy, expressive strategy, and

social strategy. The differences of strategy usage in

uttering the quality-typed argument are illustrated in

the following diagram.

Diagram 4. Pragmatic Strategy for Quality-Typed

Argumentation

In diagram 4, the boys seem somewhat

representatively outperform the girls in terms of

quality argumentation. Quality argumentation on

boys is an argumentation when they explain

something. The boys are more detail and quick

response in explaining something they know to their

mates. It is seen on the following dialogue

illustration.

(Data no. 17)

[♂] Brian : “Aku tadi lihat cacing gede banget, tapi

udah di buang sama Cello”

“I saw a super big worm, but Cello has

thrown it.”

[♂] Adeva: “Emang cacing di mana? Di dalam tanah

atau di mana?”

Where was it? Was it under the ground

or somewhere?”

[♂] Brian : “Nggak, aku lihat di atas baru jalan terus

di buang sama Celo”

“No. I saw it on the ground, just crawling,

then Cello threw it away.”

Data (17) situates when Brian stated that he saw a

worm then his friend threw it away. As for the nature

of the worm, Brian’s argument signifies the quality of

the worm size. Adeva responded by asking more

detail about the spot of the worm. Brian answered that

he saw the worm crawling on the ground, then his

friend threw it away. Reaffirmation was carried out in

detail by Brian including the event activities.

On the other side, girls tend to outperform boys

when arguing for quality in terms of control,

expressing feeling, and social. Early childhood has

already recognized the control argument strategy that

covers asking something, prohibiting over forbidden

things, and protesting over something. The girls tend

to protest when something is not fit with the norms

ICELS 2019 - International Conference on Education, Language, and Society

450

they known, while the boys tend to directly prohibit

strictly.

(Data no. 39)

[♀] Maya: “Ustadzah, Saila gangguin aku!”

“Ustadzah, Saila is bothering me!”

[♀] Sachi: “Saila tadi kamu nakal ya?”

“Saila, were you badly behaved?”

“Nanti kamu jangan main sama saila ya!”

{berbisik ke Abin}

“You don’t play with Saila. Okay?”

{Whispering to Abin}

[♂] Abin: “iya, kita main ayunan aja ya jangan sama

Saila.”

“Okay. Let’s play swings, not with Saila.”

Data 39 situates the girls indirectly protesting to

her teacher (called ustadzah) when their friends

behave out of the norms. Interestingly, the girls tend

to gather alliance when they are about to protest to

someone else who is contradicting the norms they

believed. Then, they will also ask their alliance to stay

away from the child who is considered badly

behaved.

The girls can expressively state their arguments

about what they feel. The girls and boys can show

their social arguments in the forms of greeting, saying

farewell, and asking permission. What makes it

different is that the girls were more responsive to

greet their friends than the boys were.

(Data no. 25)

During break time in Bee Class.

[♀] Milla : “Hei, Zafran, Zafran, aku udah pernah

lihat rumahnya Zafran. Rumahmu

catnya warna coklat-coklat.”

{wajah tampak ceria}

“Hey, Zafran, Zafran, I ever saw your

house. Your house paint is brown.”

{showing her cheerful face}

[♂] Zafran : “Bukan rumah aku catnya warna

putih”

“It’s not my house. My house is painted

white.”

[♀] Milla : “Tapi, aku kemarin jalan-jalan sama

ibu, aku lihat kamu di depan rumah”

“But, I took a walk with my Mom

yesterday, and I saw you in front of

your house.”

[♂] Zafran : “Aku gak lihat kamu”

“I didn’t see you.”

[♀] Milla : “Aku kan di dalam mobil, gak jalan

kaki!” {tampak kesal nada meninggi}

“I was in the car, not walking!”

{seemed upset and voice tone was increasing}

[♂] Zafran : “Oh, gitu”

“Oh, is it so?”

[♀] Milla : “Ya, sudah Zafran, aku mau main

sama Ais lagi.”

{ melambaikan tangan}

“Well, that’s it, Zafran. I want to play

with Ais.” {waving her hand}

Data no. 25 situates the quality of arguments with

social strategy comes with expressive strategy

sometimes. It shows that the girls were more

responsive in greeting their friends. Interestingly, the

girls tend to be more expressive in expressing their

feelings.

3.2.2 Strategy of Quantity Argumentation

Early childhood is already capable to express quantity

argument that stands for number of something.

Diagram 5 shows that this quantity argument is

uttered by children in two strategies, namely

representative strategy and control strategy. The boys

and the girls also had equal ability when expressing

quantity argument through both control and

representative strategies.

Diagram 5: Pragmatic Strategy for Quantity Argument

Type

The representative strategy emerges when

children want to explain a certain number of

something. The control strategy is applied to oppose

or protest their interlocutors who are false in numbers.

It is seen in data no. 4.

(Data No. 4)

[♀] Ust Vio : “Dihitung coba! {membuka buku

bergambar rumah adat dan

menghitung banyaknya rumah}

“Let’s count this!” {Opening a picture

book of custom house and counting

the number of the houses}

Argumentation Strategies of the Early Childhood Language in the Gender Perspective

451

[♀] The pupils: “satu, dua, tiga, empat, lima,enam”

“One, two, three, four, five, six.”

[♀] Ust vio : “enam yang mana ya?”

“Which six is it?”

[♀] Andien : “gak kelihatan ust..” { menyela}

“I can’t see it, Ust. ” {interrupting}

[♀] Ust vio : “nanti teman-teman menebalkan

angka yang sesuai jumlah rumah.

Kalau enam berarti seperti ini. “

{tetap melanjutkan penjelasan tidak

menghiraukan kalimat Andien}

“Later on, you all will trace the dots

of numbers based on the number of

the houses. If it is six, it will be like

this.” {Continuing her explanation

and ignoring Andien’s sentence}

[♀]Ust vio : “are you ready?”

[♀]The girls : “Yes, I am ready”

[♀]Ust Vio :“oke, ustadzah panggil Mbak

Andien” {Lalu Andien maju

mengambil buku}

“Alright. I call Mbak Andien.”

{Then, Andien comes forward to

take the book}

[♂]Kastara : “Halaman berapa ust?”

“What page, Ust?”

[♀]Ust Vio : “Halaman berapa itu Mbak Andien?

“What page is it, Mbak Andien?

[♀]Andien : “Halaman 41”

“Page 41.”

[♂]Kastara : “Hah?? Bukan ya, kamu salah!”

“Hah?? No, it’s not. You’re wrong!”

[♀]Ust vio : “41? di bawah coba dilihat, halaman

14”

“41? Look at the bottom, it’s page

14.”

[♀]Andien : “Hah, gak kok,dari sini keliatan 41.”

“Hah, no, it’s not. It seems like 41

from here.”

[♀]Sheila : “Itu kamu lihatnya kebalik dari atas.

Coba dari depan!”

{Andien membalik bukunya lalu

tersenyum dan membuka halaman

sesuai yang diminta.}

“You see it upside down. See it from

the front side!”

{Andien flips over her book, then

smiles, and opens the page as

instructed.}

Data no. 4 situates that early childhood has been

able to acknowledge numbers and the amount of

objects. However, the number is no more than two

digits. To say numbers that are more than twenty, the

teacher (Ustadzah Vio) excluded the tens and directly

said number per number. The argumentation strategy

used at the beginning was representative, which is

showing and naming the numbers of something. If it

is incorrect, the disciples will do control. Once more,

there was a different control strategy between the

boys and girls. The girls tended to protest and even

gave suggestions than the boys did. The boys tended

to directly blame and prohibit.

3.2.3 Strategy of Comparison

Argumentation

The boys and girls in early childhood are able to

giving arguments comparing something to another.

The comparison argumentation is performed using

the representative and control strategies.

In terms of comparison argumentation (se

diagram 5), the girls outperformed the boys, either

using the control strategy or the representative

strategy. The control strategy is performed by

comparing something that is meant to oppose the

arguments of the interlocutors. In this situation, the

girls were more responsive to oppose the

interlocutors’ arguments when they recognized

something compared to another and it is

contradictory. Representatively, the comparison

argumentation refers to detail explanation about

something. In this term, the girls were more detail in

comparing something. Description of this argument

strategy can be viewed in data below.

Diagram 5: Pragmatic Strategy for Comparison

Argumentation Type

(Data No. 18)

Learning about color

[♀] Ust Yani: “Teman-teman, hari ini kita akan

belajar mengenal warna! Coba siapa

yang suka warna ungu?”

“Friends, today we will learn about

colors! Who likes purple?”

ICELS 2019 - International Conference on Education, Language, and Society

452

[♂] Zafran : “Aku suka warna biru aku cowok”

{menunjukkan mainan bus warna biru}

“I like blue, because I’m a boy.”

{Showing a blue-colored bus toy}

[♀] Mila : “Aku warna ungu kan aku cewek”

{sambil menunjukkan bajunya berwarna

ungu}

“I like purple, because I’m a girl.”

{Showing her purple-colored shirt}

[♂] Sheila : “Kirana pinjemin yang warna biru!

Kamu ini warna ungu aja buat cewek!”

{memberikan pensil warna biru ke Zafran}

“Kirana, lend me the blue color! You get

the purple one, it’s for girls!”

{Giving the blue-colored pencil to Zafran}

Data no. 18 situates an interesting thing of how

the boy and girls compared the colors. Zafran as a boy

responded the teacher’s question using control

strategy to the answer to directly contrast. He did not

like the purple color, but blue color. To him, the blue

color was suit him as a boy. The statement then was

compared by Milla as a girl. Milla liked the purple

color because she is a girl. Her friend, Sheila,

supported the situation to her friend Kirana, as girls,

to not use the blue-colored pencil. Kirana was asked

by Sheila to lend the blue-colored pencil to the boy.

Kirana was given a purple-colored pencil because it

was considered to represent color for girl. The gender

stereotype issue of each kind of colors accepted by

the children is an interesting thing. In this case, the

color stereotype was influenced by the culture of

surroundings. In reality, parents dress their children

according to the children’s gender. The children

participant of this study wore clothes based on their

wants and/or their parents’ restriction. The girls will

be often dressed clothes dominated with more pink

and purple colors. The boys will be often dressed

clothes colored with other than pink and purple. The

toys that brought by the girls were also dominated

with those two feminine-stereotyped colors. On the

other side, the toys that brought by the boys will be

avoided to be dominated by those two feminine

colors.

3.2.4 Strategy of Expert Opinion

Argumentation

The boys and girls have been able to argue by

mentioning an expert opinion that is considered has

knowledge and authority. Both were equal in giving

the arguments of expert opinion. Early childhood

mentions the sayings from parents, teachers, and

adults around them who are considered know more

about something.

Diagram 6. Pragmatic Strategy for Expert Opinion

Argumentation

In mentioning opinion from someone considered

an expert, early childhood often only remembers a

half of the sayings. In this case, when their friends

incompletely give opinion based on the expert who is

accepted in their memories, those who know the

information completely will complete it and even ask

the expert to complete it. It is illustrated in the

following data.

(Data no.32)

[♀] Mila : “Aku gak mau ke dokter gigi, nanti

gigiku dibelah-belah.”

“I don’t want to visit the dentist, he will

cut my teeth.”

[♂] Syafik : “Kenapa gigi kamu sakit?”

“Why? Do you get toothache?”

[♀] Mila : “Nggak gigi aku sehat soalnya aku rajin

berdoa”

“No, I don’t. my teeth are fine because

I always pray.”

[♂] Syafik : “Ih masa berdoa aja ya, apa iya ya ust?

Gigi nya gak sakit yak, karena rajin

gosok gigi.”

“Is it so? Can we just pray for our teeth,

Ust? We don’t get toothache because

we always brush our teeth.”

[♀] Ust Yani : “Betul mas Syafiq kalo kita rajin

gosok gigi, gigi kita gak sakit.

Mungkin maksud Mbk mila, berdoa

sebelum gosok gigi ya?”

“That’s correct, Mas Syafik. If we

always brush our teeth, we will not

get toothache. Maybe what Mbak

Mila meant is praying before

brushing her teeth, isn’t?”

[♀] Mila : “Iya ust”

“Yes, it is, Ust.”

Argumentation Strategies of the Early Childhood Language in the Gender Perspective

453

Data (32) illustrates a situation when a girl named

Mila explained that she did not want to visit the

dentist because she was afraid to get a tooth medical

check. Mila stated that her teeth were fine because she

prayed diligently. Her boy friend named Syafiq

responded that her argument was peculiar. As far as

Syafiq knew, toothache is caused by the laziness to

brush teeth. Syafiq then asked the teacher’s

consideration about his opinion. The teacher then

corrected his arguments. In this context, the teacher is

the expert who strengthens Syafiq’s statement. The

teacher also fixed Mila’s opinion which was half-

accepted. The teacher understood that Mila gave her

opinions based on what she received all this time, that

as the God’s servants, we have to always pray before

starting any activities. The teacher the completed the

information about what it is meant to pray before

brushing teeth. Mila then confirmed the teacher’s

statement and realized that the expert opinion

argumentation she mentioned was not complete.

3.2.5 Strategy of Analogy Argumentation

In the case of analogy argumentation, the boys and

girls implemented the representative strategy, which

was explaining, such as Major Premise: Generally,

Case C1 is similar to case C2. Minor Premise:

Proposition A is true (false) in Case C1. Conclusion:

Proposition A is true (false) in case C2. The boys

often used an analogy of something than the girls did

(diagram 7). The description of this strategy will be

explaine by data below.

Diagram 7: Pragmatic Strategy for Analogy Argumentation

(Data no.7)

[♀] Ust. Vio : “Teman-teman Alhamdulillah hari ini

hujan.”

“Friends, Alhamdulillah. It is raining

today.”

[♀] Ais : “Ust. aku punya payung baru, beli di

pasar tadi pagi.”

“Ust, I have a new umbrella. I bought

it in the market this morning.”

[♀] Ust. Vio : “Iya, di simpan dulu ya.”

“Alright. Keep it, please.”

Data (7) shows that Ais, a girl, responded the

teacher’s statement about today’s raining. The major

premise = It is raining today. Minor premise = to stay

dry, use an umbrella. Conclusion = I bring an

umbrella today. Ais’s analogy stated that if it is

raining then we have to bring an umbrella. An

interesting thing occurs because girls tend to be more

simple and add a feature of something in analogizing

something. Ais stated that it is raining today and I

bring an umbrella, then added with and a new

adjective to explain that the umbrella was just bought

in the market.

(Data No.49)

[♂] Mecca: “Ini punyaku !!! warna-warni tapi

jelek.”

“This is mine! Colorful but ugly.”

[♂] Brian: “Punya Cello singanya lucu pake

kacamata.”

“Cello’s lion is adorable and wearing a

pair of eyeglasses.”

[♂] Nadif: “Ih singanya pacaran {sambil melihat

gambar dua singa berdekatan}

“Look! The lions are dating.” {looking at

two lions standing close at each other}

[♂] Brian: “Anak kecil gak boleh ngomong kaya

gitu dosa.”

“Children are prohibited to talk such

things, it is sinful.”

[♂] Nadif: “Ah kaya kamu ustadzah saja.”

“Ah, you’re just like ustadzah.”

[♂] Brian: “Kalo kamu berbuat dosa kamu masuk

neraka, air susunya darah.”

“If you commit sins, you’ll be in the hell,

the milk is blood.”

[♂] Nadif: “Ah kamu sukanya ngomong dosa-dosa

terus.”

“Ah, you keep talking about sins.”

Data (49) shows a similar thing to data (7). Early

childhood children are able to analogize something by

detailing the conclusion aspect. Data (49) shows

something different, where the boys tend to be

complex in analogizing something. Nadif analogized

living creatures that are close each other means they

have romantic relationships. Brian then reminded him

using the analogy of major premise = talking about

dating is a sin; minor premise = children avoid sinful

ICELS 2019 - International Conference on Education, Language, and Society

454

talks; conclusion = children avoid dating talks

because it is sinful. Nadif responded using the

analogy of major premise = Ustadzah (the teacher) is

someone who often reminds about sinful acts; minor

premise = Brian talks about sins; conclusion = Brian

is like ustadzah. Getting such response, Brian

emphasized his arguments by uttering the major

premise = human commit sins and he will be dragged

into the hell where the milk is from blood; minor

premise = Nadif has committed sin; conclusion =

Nadif will be dragged to hell if he commits sins. The

data (49) model shows that the boys were able to

express analogy arguments and respond an analogy

with an analogy, then answer it with more detail

analogy.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study show that boys and girls have

capability to give argument in daily conversation.

There are differences of argument uses in boys and

girls. The differences can be seen from the frequency

intensity of argument types uttered by them as well as

from the pragmatic strategy in the intention stating.

The girls have greater ability in qualitative and

comparison-typed arguments. On the other side, the

boys are more superior in the analogy-typed

arguments. Both the boys and girls have equal

abilities in the expert opinion and quantity-typed

arguments. In the implementation of the pragmatic

strategy, the boys applied the representative strategy

more than the girls. In contrast, the girls are more

skilled in giving arguments using the control,

expressive, and social strategies than the boys.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank to Director of Applied Linguistics

Doctoral Program in State University of Jakarta for

his support for this paper publication. We also thank

to the ICELS comitte to facilitate this paper

publication.

REFERENCES

Bova, A., & Arcidiacono, F. 2014. “Types of arguments in

parents-children discussions: An argumentative

analysis. Rivista” in Psicolinguistica Applicata/Journal

of Applied Psycholinguistics, 14(1): 43-66.

Clark, E.V. 2012. “Children, Conversation, and

Acquisition” in The Cambridge Handbook of

Psycholinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Coates, J. 2013. Women, Men, and Language: A

Sociolinguistic Account of Gender Differences in

Language. New York: Routledge, 3

rd

Edition.

Dowden, B.H. 2011. Logical Reasoning. California:

Wadsworth Publishing Company, Belmont, USA

Eckert, P. dan Ginet, S.M. 2003. Language and Gender.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haslett, B.J. 1983. “Communicative Functions and

Strategies in Children’s Conversations” in Human

Communication Research Winter 1983 Vol. 9 No. 2 pp.

114-129. Washington DC: Internasional

Communication Association.

Hellinger, M. dan Buβmann, H. 2003. “The Linguistic

Representation of Women and Men” in Gender Across

Languages Volume 3. Amsterdam: John Benjamins

Publishing Co.

Ladegaard, H.J. 2017. “Politeness in Young Childrens’s

Speech: Context, Peer Group Influence and Pragmatic

Competence” in Journal of Pragmatics 36 (2004)

pp.2003-2022. Download from

http://www.elsevier.com/locate/pragma at 23

November 2017.

Merriam, S.B. 2009. Qualitative Research: A Guide to

Design and Implementation. San Fransisco: John

Wiley and Sons.

Morrow, V. 2006. “Understanding Gender Differences in

Context: Implications for Young Children’s Everyday

Lives” in Children & Society Volume 20 (2006) pp. 92–

104.

Mukherji, P,and Albon, D. 2015. Research Methods in

Early Childhood: An Introductory Guide. London:

Sage Publications Ltd.

Musfiroh, T. 2017. Psikolingustik Edukasional:

Psikolinguistik untuk Pendidikan Bahasa. Yogyakarta:

Tiara Wacana.

Owens, R. E Jr. 2012. Language Development An

Introduction. Upper Saddle River: Pearson, 8

ht

Edition.

Riley, J. and Reedy, D. 2005. “Developing young children's

thinking through learning to write argument” in Journal

of Early Childhood Literacy 2005 5: 29.

Rowland, C. 2014. Understanding Child Language

Acquisition. New York: Routledge.

Van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. 2003. A

Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-

Dialectical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Argumentation Strategies of the Early Childhood Language in the Gender Perspective

455