Biomechanics of Shoulder Injury in Athletes

Tirza Z. Tamin

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital,

Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

tirzaediva.tamin@gmail.com

Keywords : Biomechanics of Shoulder, Shoulder Problems

Abstract : Balancing mobility and stability, the biomechanics of the shoulder provides optimal use of the thumb and

hand. More than a glenohumeral joint, the shoulder complex consists of four joints and numerous muscles

and ligaments. Injuries to the shoulder result from overuse, extremes of motion, and excessive forces.

This review describes basic shoulder biomechanics, their role in impingement and instability, and how

imaging can detail shoulder function and dysfunction.

1 INTRODUCTION

The shoulder is an engineering marvel, designed to

allow humans to maximize use of the opposable

thumb and hand in three-dimensional space. The

term shoulder is often used interchangeably with

glenohumeral joint, but the shoulder complex

actually consists of four joints and many ligaments

and muscles working synergistically. Limited bony

contact between the humeral head and glenoid fossa

allows extended range of motion at a cost of relative

instability. There must be a balance between

mobility and stability to maintain proper func- tion,

and it is this balance that embodies the biomechanics

of the shoulder complex.

Mechanical shoulder pathology typically results

when overuse, extremes of motion, or excessive

forces overwhelm intrinsic material properties and

disrupt the delicate balance of the shoulder complex

resulting in tears of the rotator cuff, capsule, and

labrum.

By reviewing basic biomechanical fundamentals

of the shoulder complex, we hope to further provide

the reader with a background to more fully

understand typical causes of more common shoulder

problems, such as impingement and instability, as

well as complex problems in the overhead athlete,

who often exhibits combined features of

impingement and instability.

2 DISCUSSION

2.1

Basic Biomechanics Of Shoulder

The glenohumeral joint is fundamentally the

central component of the shoulder complex, and yet,

like most successful groups and teams, it does not

work alone but rather depends on many individual

efforts. The other joints of the shoulder complex

include the sternoclavicular (SC), acromioclavicular

(AC), and scapulothoracic joints. The purpose of

these joints of the shoulder complex is to move and

stabilize the glenoid optimally during upper

extremity movement, similar to the coordinated

effort required to balance a spinning basketball on

your finger or a book on your head (Armfield et al,

2003).

2.2 Sternoclavicular Joint

The SC joint is a saddle joint that is a true synovial

joint. It is the only articulation of the shoulder with

the axial skeleton. Its saddle shape allows clavicular

elevation and depression (45 to –10 degrees),

anterior and posterior translation of about 15 degrees

(also called protraction and retraction, respectively),

and 50 degrees of posterior rotation along the long

axis of the clavicle. The bony articulation of the

joint consists of the primarily convex surface of

medial clavicle with the mostly concave surface of

the clavicular facet of the sternum. The SC joint

Tamin, T.

Biomechanics of Shoulder Injury in Athletes.

DOI: 10.5220/0009064200950104

In Proceedings of the 11th National Congress and the 18th Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Association (KONAS XI and PIT XVIII PERDOSRI

2019), pages 95-104

ISBN: 978-989-758-409-1

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

95

contains an intra-articular disc that helps with shock

absorption. The joint is strongly reinforced by the

anterior and posterior SC ligaments and capsule as

well as the interclavicular ligament and

costoclavicular ligaments (Armfield et al, 2003).

2.3 Acromioclavicular Joint

The AC joint is a plane joint. This type of joint

allows limited translation and rotation of two

relatively flat surfaces. The two surfaces of the

acromion and proximal clavicle are relatively

congruent but contain a variably sized intra-articular

disc that helps transmit forces evenly. The joint

provides a link between SC motion and scapular

positional changes via the strut configuration of the

clavicle. Because there is little motion at this joint,

movement initiated at the SC joint is transmitted into

scapular sliding and rotation along the

scapulothoracic plane. Joint stability results from the

AC joint capsule and its superior thickening called

the superior AC ligament. The connection between

the scapula and clavicle is further reinforced via the

coracoclavicular ligaments. In the past the joint

capsule was considered to be a relatively weak

structure, but cadaver studies have shown that

surgical transection of the capsule leads to increased

translation across the joint and these excess forces

may predispose the coracoclavicular ligaments to

failure (Debsi et al, 2001).

2.4 Scapulothoracic Joint

The scapulothoracic articulation is not a true

joint but rather the interface of the sliding scapula on

the thoracic cage. Scapular movement is essential

for upper extremity movement and it provides a

stable base for movement at the glenohumeral joint.

Scapular movement has been described in multiple

planes, including upward elevation and downward

depression, upward and downward rotation, anterior

and posterior movement along the thoracic cage

termed protraction and retraction as well small

adjustments along the AC joint plane. The major

muscles responsible for scapular movement include

the trapezius, levator scapulae, serratus anterior, and

rhomboids. Although often not considered a part of

the shoulder complex, spinal positioning is also

important for optimum scapular positioning.

2.5 Glenohumeral Joint

The fundamental central component of the shoulder

complex is the glenohumeral joint. It has a ball and

socket configuration with a surface area ratio of the

humeral head to glenoid fossa of about 3:1 with an

appearance similar to a golf ball on a tee. Overall,

there are minimal bony covering and limited contact

areas that allow for extensive translational and

rotational ability in all three planes via combinations

of several muscles.9 Stability is created through both

static (passive) and dynamic (active) mechanisms.

Static stabilizers include concavity of the glenoid

fossa, glenoid fossa retroversion and superior

angulation, glenoid labrum, which enhances glenoid

fossa depth by about 50%, the joint capsule and

glenohumeral ligaments, and a vacuum effect from

negative intra-articular pressure. It is estimated that

the labral structures represent 10 to 20% of

stabilization forces. Rotator cuff and deltoid muscle

mass also help compress the joint at rest. All of these

static restraints are important at rest, except for the

glenohumeral ligaments, which seem to be important

at extremes of motion.

During upper extremity movement the effects of

static stabilizers are minimized and dynamic or

active stabilizers become the dominant forces

responsible for glenohumeral stability. Dynamic

stabilization is merely the coordinated contraction of

the rotator cuff muscles that create forces that

compress the articular surfaces of the humeral head

into the concave surface of the glenoid fossa. This

phenomenon is known as concavity compression

and must occur during glenohumeral motion or

unwanted humeral head translation and instability

may occur, which can create forces that overload

native structures causing pathologic conditions.

Determining exact range of each movement is

difficult due to accompanying shoulder girdle

movement (Armfield, et al, 2003).

2.6 Arm Elevation

Although simply raising one’s arm is a complex task,

this motion occurs via the combination of

glenohumeral and scapulothoracic motion, together

known as scapulohumeral rhythm. This motion

usually takes place in the scapular plane, which is

about 40 degrees anterior to the coronal plane.

Overall, the ratio of glenohumeral to scapulothoracic

motion is 2:1. Initially, most motion in the first 25 to

30 degrees occurs at the glenohumeral joint. Beyond

this point, scapulothoracic motion begins and

movement at both joints occurs with a nearly 1:1

KONAS XI and PIT XVIII PERDOSRI 2019 - The 11th National Congress and The 18th Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation Association

96

ratio (Armfield et al, 2003). In addition, the humerus

must undergo external rotation to not only clear the

greater tuberosity posteriorly but also loosen the

inferior glenohumeral ligaments (IGHLs) to allow

maximum elevation. These osteokinematics require

appropriate coordinated contraction of the rotator

cuff muscles and the scapular stabilizers. The

anterior deltoid and supraspinatus muscles contract

in a coordinated fashion to initiate abduction. The

upper trapezius, lower trapezius, rhomboids, and

serratus anterior work together to create scapular

rotation.

The remainder of the rotator cuff muscles work

together to provide dynamic stability by ensuring

that the humeral head is compressed against the

glenoid fossa (concavity-compression principle).

This combined effect of rotator cuff muscular forces

results in net force effect (or summation vector)

known as a net joint reaction force. The joint

reaction forces must remain balanced during motion

via proprioreceptive feedback. If unbalanced

stability is compromised. The notion of a force

couple can be thought of in its simplest terms as a

tug of war contest between two teams. The sum

force (or vector) of the winning team causes the rope

to move in their direction. Imagine if there were

three teams; the rope would travel in a different

direction based on the strongest two teams. Now try

to imagine the complexity of the upper extremity

movement with over 20 different-sized muscles

contracting at slightly different times in all three

planes to create a desired motion.

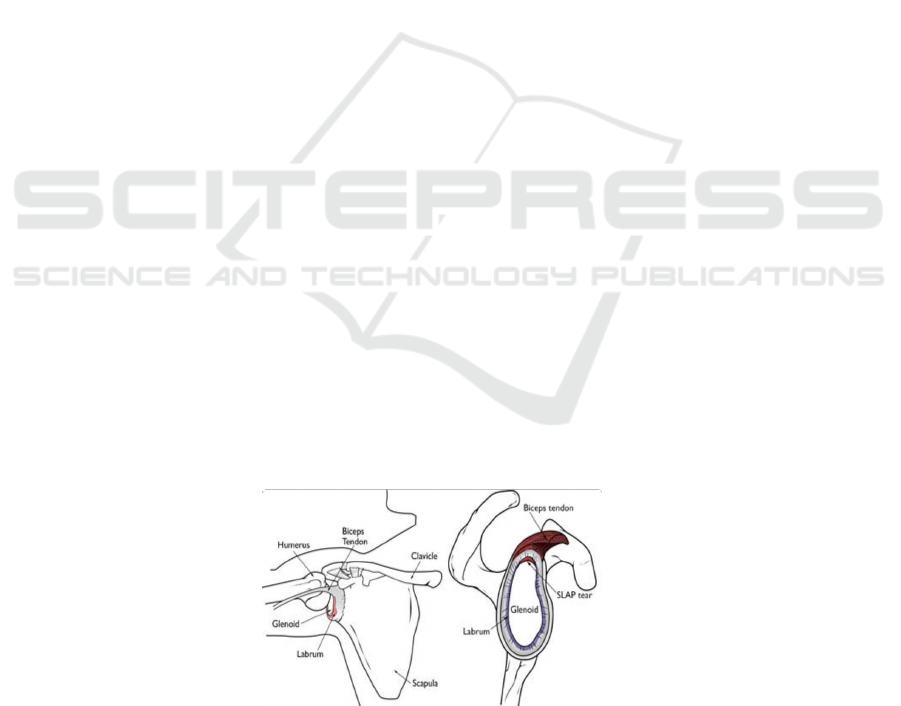

2.7 Pitching Mechanics

Although there are many other sports that involve

overhead activity, baseball pitchers have been

studied as the prototypical overhead athlete. Most

information about the mechanics of throwing was

obtained with electromyographic analysis, high-

speed videography, and three dimensional motion

analysis in baseball pitchers. The motion of pitching

has been divided into different phases, including

wind up, early cocking, late cocking, acceleration,

deceleration, and follow-through (Armfield et al,

2003).

The critical stages with respect to the shoulder

are late cocking, acceleration, and deceleration

phases. During these phases shoulder muscle activity

and load are maximized and the shoulder is most

vulnerable to injury. Coordination with the lower

legs and trunk is essential. During early arm cocking,

scapular stabilizers are active. Deltoid and

supraspinatus activity allows abduction with the

supraspinatus compressing the humeral head in the

glenoid fossa to prevent displacement. In the late

arm-cocking phase, increased activity in the

infraspinatus and teres minor creates extreme

external rotation and helps keep the humeral head

centered within the glenoid fossa, preventing

anterior displacement. This phase is also

characterized by activity in the subscapularis,

pectoralis major, and latissimus dorsi to help

stabilize and strengthen the anterior aspect of the

shoulder to prevent anterior translation of the

humeral head.

it also forces the head of the

humerus forward which places significant

stress on the ligaments in the front of the

shoulder. Over time, the ligaments loosen,

resulting in greater external rotation and

greater pitching speed, but less shoulder

stability

(Armfield et al, 2003)

.

During the acceleration phase there is high

activity of the internal rotators (latissimus dorsi,

pectoralis major, and subscapularis) with

complimentary activation of teres minor posteriorly

in an effort to center the humeral head. At the same

time scapular stabilizers are actively contracting to

create a stable base for humeral movement during

which time large angular and torsional forces are

created. During deceleration all posterior muscles

are active, especially teres minor, which

eccentrically contracts to limit internal rotation.

Once the ball is released, follow-through

begins and the ligaments and rotator cuff

tendons at the back of the shoulder must

handle significant stresses to decelerate the

arm and control the humeral head.

Figure 1: Pitching Mechanism.

2.8 Mechanical Abnormalities of the

Shoulder

Many people believe that many overhead athletes

experience subclincal instability (i.e., no subluxation

or dislocation on physical exam), which leads to

contact of the humeral head and labrum causing

pathology of the rotator cuff and surrounding labrum.

This subclinical instability is known as functional or

Biomechanics of Shoulder Injury in Athletes

97

microinstability and different theories regarding the

pathomechanics exits.

The two most commonly described mechanical

dysfunctional abnormalities of the shoulder are

rotator cuff impingement and glenohumeral

instability. Typical connotations of impingement

include individuals over 40 with pain during

movement. Instability stereotypically affects young

athletic males with gross instability resulting in

dislocation. For rotator cuff dysfunction that can be

intermingled, particularly in the overhead athlete

(Armfield et al, 2003).

2.9 Rotator Cuff Dysfunction

Most rotator cuff tears are due to end-tage

mechanical impingement of the cuff by the

coracoacromial arch during arm elevation has been

the cornerstone of diagnosis and treatment of rotator

cuff dysfunction. Bigliani correlated acromial

morphology, Aoki analyzed acromial slope, and

others have identified factors that cause narrowing

of the supraspinatus outlet that leads to impingement

and cuff tears. The coracoacromial ligament is

attached to the undersurface of the acromion and the

tip of the coracoid. It is often enlarged in patients

with rotator cuff pathology. It also serves as a

restraint to glenohumeral superior migration in end-

stage cuff tears. Traction forces at its acromial and

coracoid attachments may lead to spur formation,

resulting in subacromial and subcoracoid

impingement. Impingement involving narrowing of

the supraspinatus outlet is known as extrinsic or

outlet impingement.

6

Secondary extrinsic

impingement results from inferior narrowing of the

outlet from the rising humeral head in the setting of

instability or scapulothoracic dysfunction.

Regardless of primary or secondary types, both

forms repetitively damage the cuff tissue and

predispose it to eventual failure (Armfield et al,

2003).

This concept emphasizes the need for a

biomechanically stable rotator cuff. A person could

have a small cuff tear and be highly symptomatic

depending upon the location of the tear and its effect

on the balance of forces in the shoulder. Small

tendon tears can induce reflex inhibition of muscle

contractility, which can further lead to cuff

imbalance and symptoms, whereas a small

perforative full-thickness tear may be

biomechanically silent and clinically meaningless.

Consequently, it is important to describe not only the

type of tear but also its size, extent, and exact

location for the referring surgeon (Pandev and Jaap,

2015).

Muscles of the rotator cuff are active during

various phases of the throwing motion.

16

During the

late cocking and early acceleration phases, the arm is

maximally externally rotated, potentially placing the

rotator cuff in position to impinge between the

humeral head and the posterior-superior glenoid.

Known as “internal impingement” or “posterior

impingement,” this may place the rotator cuff at risk

for undersurface tearing (articular sided).

Conversely, in the deceleration phase of throwing,

the rotator cuff experiences extreme tensile loads

during its eccentric action, which may lead to injury

(Dugas and Andrew, 2003). Rotator cuff tears in the

overhead athlete may be of partial or full thickness.

The history of shoulder pain either at the top of the

wind-up (acceleration) or during the deceleration

phase of throwing should alert the examiner to a

rotator cuff source of pain or loss of function. Any

history of trauma, changes in mechanics, loss of

playing time, previous treatments, voluntary time off

from throwing, and history of previous injury should

be noted. Rotator cuff tears may be caused by

primary tensile cuff disease (PTCD), primary

compressive cuff disease (PCCD), or internal

impingement. PTCD results from the large,

repetitive loads placed on the rotator cuff as it acts to

decelerate the shoulder during the deceleration phase

of throwing in the stable shoulder. The injury is seen

as a partial undersurface tear of the supraspinatus or

infraspinatus (Lynn and Lippert, 2003). PCCD is

found on the bursal surface of the rotator cuff in

throwers with stable shoulders. This process occurs

secondary to the inability of the rotator cuff to

produce sufficient adduction torque and inferior

force during the deceleration phase of throwing.

Processes that decrease the subacromial space

increase the risk for this type of pathology. Partial-

thickness rotator cuff tears can also occur from

internal impingement (Dugas and Andrew, 2003).

2.10 Clinical Significance

Rotator Cuff Injury

Rotator cuff tears are either partial thickness or

full-thickness tears. Partial thickness tears occur at

the articular (most commonly) or bursal side of the

rotator cuff tendons.

The patient's age, baseline shoulder

function,tear size, chronicity, and degree of tendon r

etraction are several critical elements to be

considered when deciding how to manage each

patient most appropriately. The supraspinatus tendon

KONAS XI and PIT XVIII PERDOSRI 2019 - The 11th National Congress and The 18th Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation Association

98

is the tendon most commonly injured of the rotator

cuff muscles, followed by infraspinatus,

subscapularis, and teres minor. The teres minor

tendon is only rarely involved in rotator cuff

injuries. The subscapularis tendon tear can be

associated with a biceps tendon dislocation from the

bicipital tendon groove moving into the

subscapularis tendon medially (Eovaldi et al, 2018).

Confirmation of intra-articular tendon tears is by

the absence of the biceps tendon in the empty

bicipital groove.18 Labral injuries and Dislocations

Multiple types of shoulder labral injuries can occur

in different patient populations. One particularly

common injury subgroup includes young athletes

afflicted with a traumatic shoulder dislocation. In

the setting of glenohumeral instability, clinicians

should recognize the importance of not only a

recurrent dislocation, but the risk of increased bone

loss and soft tissue compromise which may

ultimately affect the outcome following surgical

repair (Eovaldi et al, 2018).

Glenohumeral instability, especially in the

setting of trauma, is most commonly seen anteriorly.

Posterior shoulder instability can be seen in

weightlifter or football linemen. Rare dislocation

patterns include the superior and inferior

glenohumeral dislocation (luxatio erecta). It is

important to note that in the setting of

multidirectional instability (MDI), especially in the

case of bilateral ligamentous laxity or in a patient

with a personal or family history of a connective

tissue disorder, the probability of recurrent

instability is relatively common. The mainstay

treatment for these injuries centers on physical

therapy and shoulder strengthening programs

(Eovaldi et al, 2018).

Para-labral cysts are most often seen in

association with glenoid labral tears. Para-labral

cyst formation can cause subsequent nerve

compression and denervation of shoulder

muscles. The suprascapular nerve is susceptible to

compression from a para-labral cyst due to its

location as it passes through the suprascapular and

spinoglenoid notches adjacent to the anterior-inferior

labrum. The subscapular nerve is also susceptible to

compression from a para-labral cyst in the

subscapular recess. Isolated atrophy of the teres

minor implies injury to the axillary nerve (Cowan et

al, 2018).

2.11 Adhesive Capsulitis

The cause of frozen shoulder is deposition of

hydroxyapatite crystals into the muscle tendon.

The shoulder is the most common site of

hydroxyapatite calcification in the human body. The

supraspinatus tendon is the most common site of

hydroxyapatite crystal deposition. Frozen shoulder is

associated with diabetes mellitus but may also be

associated with coronary artery disease, cerebral

vascular disease,

rheumatoid arthritis, and thyroid disease (Friedman

et al, 2015).

There are numerous lesions that may occur in the

overhead athlete. Tendonitis, tendonosis, and

bursitis are 3 separate clinical entities for which the

names are often incorrectly used interchangeably.

Tendonitis is inflammation of the tendon. In many

cases, it is actually the tendon sheath that is inflamed

and not the tendon itself. Bursitis is inflammation of

the subacromial bursa. Tendonosis implies

intratendonous disease, such as intrasubstance

degeneration or tearing. The patient clinical

presentation of tendonitis or tendonosis of the rotator

cuff are pain with overhead activity and weakness

secondary to pain. The symptoms in the thrower are

pain during the late cocking phase of throwing,

when the arm is in maximal ER, or pain after ball

release, as the muscles of the rotator cuff slow the

arm during the deceleration phase (Wilk et al, 2009).

Weakness of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus

are common findings in throwers with shoulder

pathology; but asymmetric muscle weakness in the

dominant shoulder is often seen in the healthy

thrower. Differential diagnosis of tendonitis versus

tendonosis is based on MRI and duration and

frequency of symptoms. On MRI, the patient with

tendonitis will exhibit inflammation of the tendon

sheath (the paratenon); conversely, when tendonosis

is present, there exists intrasubstance wear (signal)

of the tendon. Tendonitis/tendonosis is most

frequently an overuse injury in the overhead athlete

and does not usually represent an acute injury

process. The symptoms frequently occur early in the

season, when the athlete’s arm is not conditioned

properly. These injuries may also occur at the end of

the season, as the athlete begins to fatigue. If the

athlete does not participate in an in-season

strengthening program to continue proper muscular

conditioning, tendonitis/tendonosis may also

develop. Specific muscles (external rotator muscles

and scapular muscles) may become weak and

painful due to the stresses of throwing (Wilk et al,

2015).

Biomechanics of Shoulder Injury in Athletes

99

2.12 Internal Impingement

Internal impingement was first described in 1992 by

Walch and associates in tennis players. They

presented arthroscopic clinical evidence that partial,

articular-sided rotator cuff tears were a direct

consequence of what they termed “internal

impingement.” Internal impingement is

characterized by contact of the articular surface of

the rotator cuff and the greater tuberosity with the

posterior and superior glenoid rim and labrum in

extremes of combined shoulder abduction and ER.

In overhead throwing athletes, it appears that

excessive anterior translation of the humeral head,

coupled with excessive glenohumeral joint ER,

predisposes the rotator cuff to impingement against

the glenoid labrum. Repeated internal impingement

may be a cause of undersurface rotator cuff tearing

and posterior labral tears. It is important that the

underlying laxity of the glenohumeral joint be

addressed at the time of treatment for an internal

impingement lesion to prevent recurrence of the

lesion (Manske et al, 2013).

Burkhart et al have proposed that restricted

posterior capsular mobility may result in IR deficits

and may cause pathologic increases in internal

rotator cuff contact and injury. Patients with internal

impingement usually describe an insidious onset of

pain in the shoulder. Pain tends to increase as the

season progresses. Symptoms may have been

present over the past couple of seasons, worsening in

intensity with each successive year. Pain is usually

dull and aching, and is located over the posterior

aspect of the shoulder. Late cocking phase seems to

be most painful. Loss of control and velocity is often

present secondary to the inability to fully externally

rotate the arm without pain. On physical

examination, pain may be elicited over the

infraspinatus muscle and tendon with palpation. Pain

to palpation is more often posterior, in contrast to

rotator cuff tendonitis, which usually elicits pain to

palpation over the greater tuberosity. With internal

impingement, patients usually have full ROM. In

both the normal and pathologic thrower’s shoulder

the dominant arm tends to have 10° to 15° more ER

and 10° to 15° less IR with the arm abducted to 90°,

compared with the nondominant arm. The most

common presentation is for the overhead athlete to

have 1+ to 2+ anterior laxity and 2+ posterior laxity.

Inferior laxity is often present. Most provocative

tests are negative. The most frequent provocative

exam to elicit pain is the internal impingement sign,

described earlier (Rose et al, 2018).

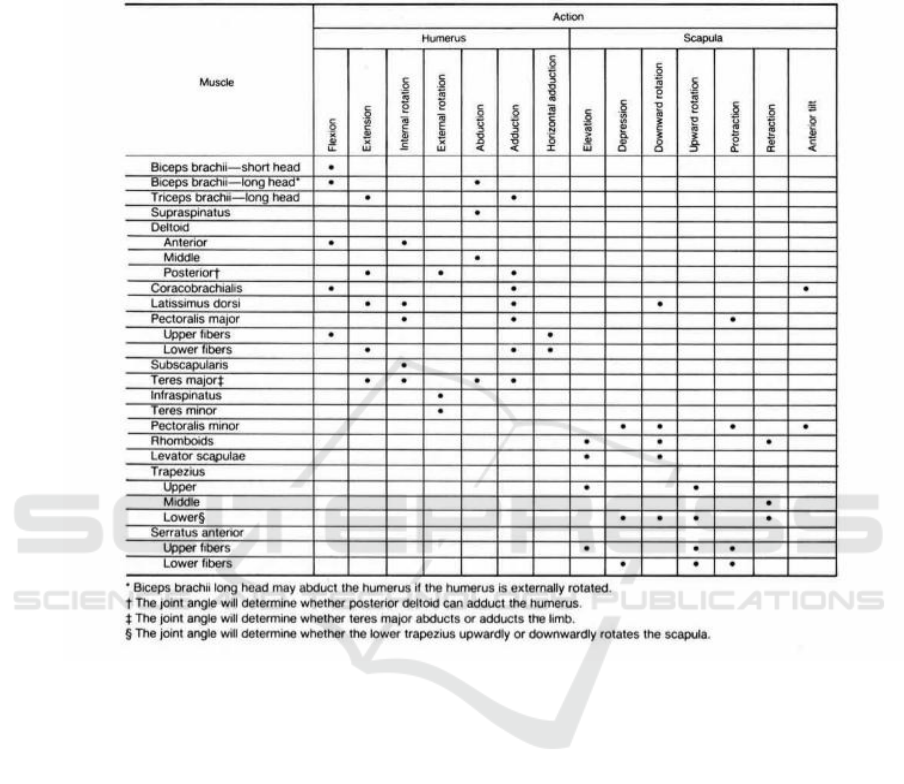

2.13 Superior Labrum Anterior to

Posterior (SLAP) Lession

SLAP lesions are a complex of injuries to the

superior labrum and biceps anchor at the glenoid

attachment. Patients who have SLAP lesions fall

into 2 basic categories. The first consists of overhead

athletes, most commonly baseball players, with a

history of repetitive overhead activity and no history

of trauma. The second category involves patients

with a history of trauma. Burkhart et al have

described the peel-back lesion of the superior labrum,

which frequently occurs in the overhead athlete.

Peel-back lesions are considered a type II SLAP

lesion. The athlete often presents to the practitioner

with complaints of vague onset of shoulder pain and

possibly problems with velocity, control, or other

throwing complaints. The patient may complain of

mechanical symptoms or pain in the late cocking

phase, often poorly localized. This sign occurs when

the arm is placed in abduction and external rotation,

which causes the biceps anchor to twist posteriorly

because of its loose attachment. Typical symptoms

are a catching or locking sensation, and pain with

certain shoulder movements. Pain deep within the

shoulder or with certain arm positions is also

common. The diagnosis of SLAP lesions can be very

difficult, as symptoms can mimic rotator cuff

pathology and glenohumeral joint instability.

Definitive diagnosis can only be made by

arthroscopy (Wilk et al, 2013).

2.14 Thrower’s Exostosis

Thrower’s exostosis is an extracapsular ossification

of the posteroinferior glenoid rarely seen except in

older longtime throwers. This condition is a result of

secondary ossification involving the posterior

capsule, probably due to repetitive trauma. The

osteophyte is thought to originate in the glenoid

attachment of the posterior band of the inferior

glenohumeral ligament, possibly from traction

during deceleration. Patients often have a tight

posterior capsule, with capsular contracture and

asymmetric shoulder motion with an IR deficit. This

lesion can often mimic internal impingement. Pain is

often found in the posterior part of the shoulder and

is worse in late cocking. Patients often describe a

pinching sensation during throwing. Pain usually is

relieved by rest. Plain radiographs will assist in

differentiating this lesion from internal impingement

(Wilk et al, 2009).

KONAS XI and PIT XVIII PERDOSRI 2019 - The 11th National Congress and The 18th Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation Association

100

2.15 Acromioclavicular Joint Injury

Acute acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) injuries can

occur due to a direct force to the acromion typically

with the shoulder adducted, or from an indirect force

elsewhere in the body, for example, a fall onto an

outstretched arm. Patients present with acute

localised pain, swelling and sometimes redness.

Injuries can range from a simple acromioclavicular

ligament sprain that can be managed conservatively,

to ligament tears with ACJ displacement that often

require surgery. Chronic ACJ pain can occur

following acute ACJ injuries or from repeated

irritation to the joint that can develop into osteolysis

or osteoarthritis. These chronic changes can be

caused by sports that involve throwing or lifting

weights. The symptoms will be similar to acute ACJ,

but the pain develops insidiously (Leung, 2016).

2.16 Clavicle Fracture

Clavicle fractures, particularly the mid-third of the

clavicle, are the most common acute shoulder

injuries and account for one in twenty adult fractures.

Fractures located more laterally can disrupt the

acromioclavicular joint. Over 80% of clavicle

fractures can be managed conservatively These

injuries usually occur from a fall onto the clavicle or,

less frequently, a direct blow to the clavicle. Patients

may be involved with contact sports or other at- risk

sports such as horse-riding and cycling. They

present with acute localised pain with swelling and

sometimes visible deformity. Acute injuries are

more likely to present to the hospital Accident &

Emergency Department than primary care (Leung,

2016).

2.17 Glenohumeral Internal Rotation

Deficit (GIRD)

GIRD is defined as a loss of internal rotation in

excess of the adaptive gain in external rotation in the

throwing shoulder (Lin et al, 2018). Clinically

relevant GIRD has been defined as a loss of greater

than 25° of internal rotation in the throwing shoulder

relative to the nonthrowing side (Bukhart, 2003).

The biomechanical model of GIRD is based on the

contractures of the posterior capsule and posterior

band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament

discussed previously. On magnetic resonance (MR)

images, thickening of the posteroinferior capsule is

present, which can be an important clue to look for

concurrent findings in the labrum and rotator cuff.

The proposed pathologic cascade due to GIRD starts

with posterior soft tissue contractures causing

posterosuperior shift of the humeral head, resulting

in excessive external rotation.

This “peels back” the biceps anchor under

extreme tension, subjecting the posterosuperior

structures, including the labrum, to injury. The

extreme external rotation also submits the rotator

cuff to torsional or twisting injury, leading to

eccentric fiber failure and undersurface tearing,

which is distinct from the compressive injury in the

internal impingement model. While prior data

suggested an association between GIRD and an

increased risk for shoulder injuries, specifically

superior labrum anteroposterior (SLAP) tears, a

more recent study proposes that external rotation

insufficiency 5° difference in external rotation

between throwing and nonthrowing arms) rather

than GIRD is associated with shoulder injury.

Nevertheless it is still current practice to manage the

majority of athletes with GIRD via a stretching

regimen, with the 10% who fail conservative

treatment pursuing posterior capsulotomy and SLAP

tear repair (Lin et al, 2018).

Figure 2: The Labrum and SLAP Tear (Left: Labrum helps to deepen the shoulder socket; Right: cross section view of

shoulder socket shows tipical SLAP tear)

Biomechanics of Shoulder Injury in Athletes

101

Table 1: Muscle Actions at the Shoulder

KONAS XI and PIT XVIII PERDOSRI 2019 - The 11th National Congress and The 18th Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation Association

102

Table 2: Sports-related shoulder conditions and their possible clinical signs.

Rotator cuff

tendinopathy

Asymmetry and muscle wasting

Palpation tenderness at the

greater tubercle (insertion sites of

three rotator cuff muscles)

Reduced active ROM

Passive ROM intact

Reduced power on resisted movements

Impingement signs

Rotator cuff tears

Shoulder shrug appearance

Partial or no active ROM

Passive ROM often intact

Reduced power on resisted movements

Drop-arm sign in complete tears if

arm cannot be

actively maintained

at 90

○

abduction

Impingement signs

Glenoid

labral injury

Palpation tenderness in the

anterior shoulder structures

Swelling if acute

Reducedexternalrotationandor abduction ROM

Reduced poweron resisted

movements

Biceps load 2 test positiveif

superior labrum

anterior posterior (SLAP) tear

Speed’s test positive if SLAP

Yergason’s test positiveif SLAP

Jerk’s test positive if postero-inferior labral injury

Shoulder

instability

and

dislocation

Prominent humeral head if anter

ior dislocation

Swelling ifacute

Reduced active and passive ROM

if dislocated

Increased active or passive ROM

if instability with

laxity

Apprehension test positive if anterior dislocation

Jerk’s test positive if postero-

inferior dislocation

Upper arm axillary nerve sensation can be reduced

in anterior dislocations

Clavicle Fracture

Localised swelling with deformity

Clavicle shortened or angulated

Localised bony tenderness

ACJ Injury

Step deformity and swelling if

acute

Localised ACJ tenderness

Scarf test positive

Impingement signs if chronic

Biceps

tendinopathy

Bicipital groove tenderness

Speed’s test positive

Yergason’s test positive

REFERENCES

Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, Wirth MA, Lippitt SB. 2009.

The Shoulder. Fourth Edition. Volume One. Saunders

Elsevier: Philadelpia

Lin DJ, Wong TT, Kazam JK. 2018. Shoulder Injuries in

the Throwing Athlete.Radiology. 286(2): 370-87

Eovaldi BJ. Varacallo M. 2018. Anatomy, shoulder and

upper limb, shoulder muscle. NCBI Bookshelf.

[accessed online at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534836/]

Lynn s. Lippert. Clinical Kinesiology and Anatomy of the

Upper Extremities. 4ed.

Armfield DR, Stickle RL, Robertson DD, Towers JD,

Debski RE. 2003. Biomechanical Basis of Common

Shoulder Problems. Seminars in Musculoskeletal

Radiology.7(1): 5-20.

Biomechanics of Shoulder Injury in Athletes

103

Pandev V. Jaap WW. 2015. Rotator cuff tear: A detailed

update. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil

Technol. 2(1):1-14

Dugas JR, Andrews JR. 2003. Throwing injuries in the

adult. In: DeLee JC, Drez D, Miller MD, eds. DeLee

and Drez’s Orhopaedic Sports Medicine. Philadelphia,

PA: Elsevier Science.

Carroll KW, Helms CA, Otte MT, Moellken SM, Fritz R.

2003. Enlarged spinoglenoid notch veins causing

suprascapular nerve compression. Skeletal Radiol.

Feb;32(2):72-7.

Cowan PT, Varacallo M. StatPearls

[Internet].2018. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island

(FL). Anatomy, Back, Scapula.

Friedman JL, FitzPatrick JL, Rylander LS, Bennett C,

Vidal AF, McCarty EC. 2015. Biceps Tenotomy

Versus Tenodesis in Active Patients Younger Than 55

Years: Is There a Difference in Strength and

Outcomes? Orthop J Sports Med.

Wilk KE, Obma P, Simpson CD, Cain EL, Dugas J,

Andrews JR. 2009. Shoulder Injuries in the Overhead

Athlete. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical

Therapy.39(2):38-54

Manske RC. Grant NM. Lucas B. 2013. Shoulder posterior

internal impingement in the overhead athlete. Int J

Sports Phys Ther.8(2):194-204.

Rose MB, Noonan T. 2018. Glenohumeral internal

rotation deficit in throwing athletes: current

perspectives. Open Access J Sports Med. 9:69-78.

Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Cain EL, Dugas JR, Andrews JR.

2013. The recognition and treatment of superior labral

(SLAP) lesions in the overhead athlete. Int J Sports

Phys Ther.8(5):579-600

Leung R. 2016. Common sports-related shoulder injuries.

Macquarie university Library. [accessed online at:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1755738

016678436]

Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. 2003. The disabled

throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part I:

pathoanatomy and biomechanics.

Arthroscopy.19(4):404–420.

KONAS XI and PIT XVIII PERDOSRI 2019 - The 11th National Congress and The 18th Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation Association

104