SMES and HEI Collaboration: Improving SMEs’ Performance and

Knowledge Management Capability to Cope with Economic

Disruption

Dorojatun Prihandono, Wahyono, Andhi Wijayanto, Corry Yohana, and Made V. Permana

Management Department, Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Semarang

Business and Commerce Education, Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta

Keywords: Entrepreneurial, Learning, Knowledge, Capability, Engagement, Performance.

Abstract: Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) face challenging competition in this economic disruption era. Effort to

improve competitiveness through performance and knowledge management capability has become a must to

cope with the economic disruptions. Performance and knowledge management capability in SMEs need to be

addressed to improve their competitiveness. Higher Education Insitution (HEIs) and SMEs collaboration has

become a tool to improve SMEs’ performance and knowledge management. The aim of this study is to

examine relationship between entrepreneurial orientation on organisational learning; the role of HEI

engagement in moderating entrepreneurial orientation on organisational learning; relationship between

organisational learning on organisational performance and organisational learning on knowledge management

capability. This study applies PLS SEM analysis. SMEs business owners in Semarang, Magelang, Pekalongan

and Grobogan region are respondents of this study. Results of this study shows that entrepreneurial orientation

has positive influence on organisational learning; there is no moderation effect of HEI engagement on

entrepreneurial orientation and organisational learning; organisational learning has positive influence on

organisation performance and organisational learning influence positively on knowledge management

capability.

1 INTRODUCTION

SME sector becomes the backbone of global

economy in recent decades. According to

International Trade Centre, in 2015, 95% of

companies in this globe are SMEe. They provide 50%

of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which

consist of 420-510 million companies, and 310

million of them are in emerging markets. SMEs as a

business entity covers wide array of business

formations, ranging from sole-proprietorship to

massive company. Alongside its capability to obtain

certain level of performance, SME also must have a

sound knowledge of management capability. Based

on that fact, it is pertinent that SMEs must focus on

several factors which are very crucial in enhancing

the SMEs’ withstand on economic disruptions, those

factors are capability in managing knowledge,

entrepreneurial orientation, learning aspect of

organisation, and SMEs’ performance themselves

(Dess et al., 2003; Ashforth et al., 2007; Wiklund et

al., 2009; Sanzo et.al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2012). To

be able to obtain better performance and knowledge

management capability, SMEs must have

organisational learning factor which is influenced by

entrepreneurial orientation (Dess et al., 2003;

Ashforth et al., 2007). Asad Sadi and Henderson

(2011) emphasise that SMEs in global relationships

context can be in form of licensing, joint venture,

franchising and other strategic alliances formation,

and to attain sound relationships in the alliances,

performance and capability in managing knowledge

transfer are needed. University as higher education

institution (HEI) has responsibility in enhancing

those two factors, performance and managing

knowledge transfer (Tedjakusuma, 2014).

Establishing better relationship between

entrepreneurial orientation and organisational

learning and role of universities is needed to have a

clear view of how those factors related among others.

Moreover, this study also attempts to respond for

further research in SMEs performance and

knowledge management capability which is

conducted in specific sector, the higher education

Prihandono, D., Wahyono, ., Wijayanto, A., Yohana, C. and Permana, M.

SMES and HEI Collaboration: Improving SMEs’ Performance and Knowledge Management Capability to Cope with Economic Disruption.

DOI: 10.5220/0009198800510061

In Proceedings of the 2nd Economics and Business International Conference (EBIC 2019) - Economics and Business in Industrial Revolution 4.0, pages 51-61

ISBN: 978-989-758-498-5

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

51

institution or university. (Chaston, 2001; Vargo &

Seville, 2011; Tedjakusuma, 2014).

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Knowledge Based View (KBV) is derived from

resource-based theory and organisational theory; by

applying knowledge, an organisation can explore its

resources to increase competitive advantage and

creating more consumer value (Nonaka, 1994; Hsung

& Tang, 2010). Grant dan Baden-Fuller (2004)

emphasised that there are two major rationales in

explaining KBV, the first is knowledge acquisition by

organisational learning and secondly is by applying

organisational efficiency advantage in strategic

alliance to exploit knowledge.

Collaboration between SMEs and university is

important key in developing a certain level of trust

between the two parties. Furthermore, the level of

trust can accelerate knowledge transfer to obtain

strategic alliance and innovation (De La MAza et al.,

2012). Petkovska (2015) emphasised that naturally

SMEs are centre of innovation initiation, and they

produce a lot of innovative product and services to

fulfil consumer needs. Networking can be a capital

source for SMEs as well. Gilmore et al. (2011)

emphasised that SMEs have distinctive approach

compare to larger companies, so called the marketing

for networking. This kind of networking is suitable

for SMEs due to limitation of resources, knowledge

specialist and impact on market (Chaston & Mangles,

2000; European Commission, 2005 in Jamsa et al.,

2011,p.143). One of the strategies in SMEs

networking is to establish relationship with Higher

Education Institution (HEI) or universities.

HEIs have become SMEs’ resource of knowledge

and technology for decades through research and

technology research and development (Guston,

2000). Based on previous statement, there are two

questions that can be discussed; the first is “What has

been done by the universities as knowledge

resources?” and the second is “Why are the

universities doing all of these things?”. Universities

or HEIs has obligation to their stakeholders, including

business community. Gunasekara (2006, p.4) stated

in philosophical way that “The role of university in

the development of regional innovation systems may

be categorised using a duality of spanning generative

and developmental categories…”; Thus, in theory,

the universities’ roles in developing innovation in a

region has evolved in the last two decades, from spill

overs approach to stimulate the economic

development in a region (Gunasekara, 2006).

Furthermore, government is perceived to be able to

add its involvement in expertise transferfor the SMEs,

for instance in form of business incubator

(Tedjasuksmana, 2014). The involvement is also

supposed to enhance the SMEs’ managers active

support both in training and accompaniment

programmes (Tedjasuksmana, 2014). This will

determine success of the collaboration between SMEs

and universities (Peças & Henriques, 2006).

Lambooy (2004) stated that to improve the SMSs’

competitiveness, SMEs need to pay more attention on

creativity within the organisation due to variations of

creativity levels owned by each individual, so called

the human capital. The human capital resource within

the SMEs can be improved by utilising network social

capital (Street & Cameroon, 2007: Bosworth, 2009).

The human capital resource in the SMEs become

pertinent factors in knowledge transfer from HEIs to

SMEs, this type of knowledge transfer is called

“vertical transfer”, the transfer is in form of

operation/production process (Decter et al., 2007).

This type of transfer also realtively hard to transfer

due to knowledge complexities. In order to analise the

HEIs and SMEs collaboration based on previus

studies (Guston, 2000; Tödtling & Kaufmann, 2001;

Lambooy, 2004; Charles, 2006; Peças & Henriques,

2006; Gunasekara, 2006; Decter et al., 2007;

Tedjasuksmana, 2014), this study develop a

collaboration framework between HEIs and SMEs to

enhance the SMEs performance and competitiveness

in coping with global competition as follows:

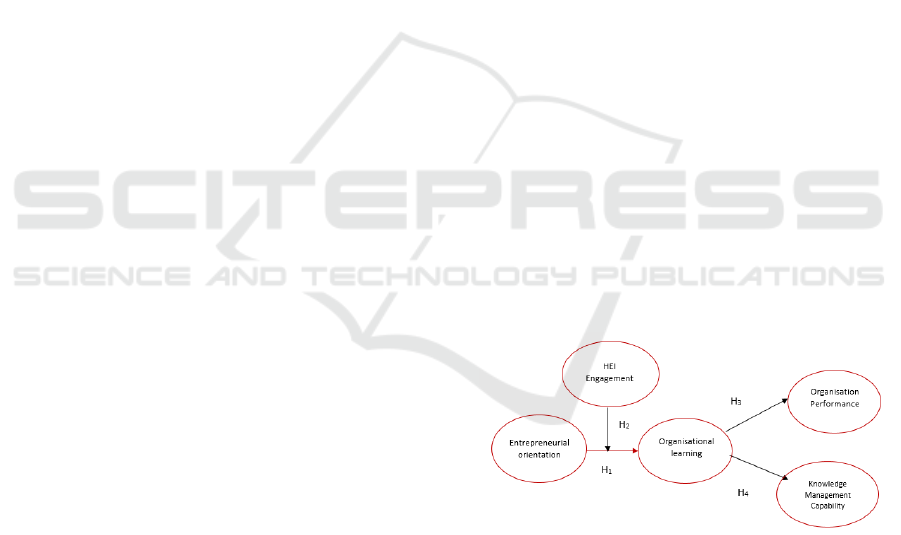

Figure 2.1: HEI-SME Collaboration Model

3 HYPOTHESES

DEVELOPMENT

3.1 Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO)

and Organisational Learning (OL)

A business entity which embrace entrepreneurial

orientation (EO) is expected to increase its

EBIC 2019 - Economics and Business International Conference 2019

52

organisational learning (OL), especially for its

innovative products and services (Chaston et al.,

2001). An organisation with high level of EO will

seek for knowledge actively. Applying EO will

provide the organisation with better market position

to obtain and combine specific series of knowledge

needed. Study by Ashforth et al. (2007), emphasised

that proactive behaviour is embedded in EO will

facilitate firm’s learning process. Furthermore, Dess

et al. (2003) argued that by commencing knowledge

development through EO, a firm can form an

effective corporate network to enhance innovation.

Based on that description, the first hypothesis is:

H

1

: Entrepreneurial Orientation has positive influence

on Organisational Learning

3.2 Higher Education Institution

Engagement (HE) Moderates the

Relationship between EO and OL

SMEs have resources limitation, that is way SMEs

need to get access for various kinds of resources, in

this context, the knowledge. In terms of knowledge,

SMES can apply networking resources with HEIs in

their environment to gain knowledge (Wiklund et al.,

2009). Moreover, HEIs have a wide array of

resources especially the knowledge-based 21

st

century knowledge (Wilson, 2012: 2). Thus, that it

can be concluded that SMEs involvement or

engagement with HEIs is very pertinent. This

involvement or engagement can be a useful resource

to support growth and development.

Previous study emphasised that joint research

between firm and HEIs acts as vehicle to enhance the

involvement and commitment, as a result it has

massive impact on firm’s resources access on

knowledge (Huggins et al., 2008). HEIs provide

SMEs with several services such as accompaniment,

acceleration The form of services offered and

provided by higher education institutions such as

universities to small companies includes various

matters of business assistance, such as:vextension

services, and accelerator and outreach programs

designed to transfer academic expertise in the form of

the latest technology and business practices to

improve product performance, product quality, and

process efficiency (Huggins et al., 2008). Through

engagement with universities, businesses or

companies can get access to the latest research in their

fields and employees who have an innovative spirit in

the form of graduates or innovative students in a

workplace (BIS, 2012); they can also get access to a

series of innovative ideas

The relationship between higher education

institutions and industry has become a popular

mindset or direction of knowledge today, where

academics act as providers of knowledge through

university-industry collaboration that encourages

learning exchanges in gaining knowledge (Baba et al.,

2009). Philbin (2012) suggested that university

involvement will bridge the learning process,

university collaboration with business is a form of

strategic alliance that provides a foundation for

learning. Furthermore, companies that collaborate

with higher education institutions gain access to

specific knowledge that in the future can be further

developed to improve the competitiveness of the

industry or the company itself (Philbin, 2012). If the

level of science and technology-based knowledge

resources can be transferred through university

involvement, both Resource-Based View (RBV) and

Knowledge Based Theory (KBT) show that small and

medium enterprises with high EO levels and working

with universities will have advantages in terms of OL

Moreover, companies that are aware of the benefits of

business / university involvement are able to integrate

academic capabilities with their product and service

development opportunities (Philbin, 2012). Afore

mentioned earlier, companies try to create appropriate

value in relations between companies by utilising

their resources to complement useful resources

(Anatan, 2013). Given that EO is a strategic resource,

it can be assumed that business / university

collaboration is a complementary pertinent resource

that will increase the OL level. Therefore, the second

hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H

2

: HEI engagement positively moderates the

relationship between EO and OL

3.3 Relationship between

Organizational Learning (OL) and

Organizational Performance (OP)

Huber (1998) stated that OL increases ability of a

business organisation to innovate, which in turn can

have an impact on improving organisational

competitiveness and performance. Rhodes et al.

(2008) also emphasised that OL has focal positive

relationship with innovation process in Indonesia,

specifically in knowledge transfer process to improve

company-organisational performance (OP)

performance. Theriou and Chatzoglou (2008)

suggested that knowledge management (KM) and OL

play a pertinent role in creating organisational

capabilities, which leads to sound performance. Yang

et al. (2007) provided a more in-depth assessment of

SMES and HEI Collaboration: Improving SMEs’ Performance and Knowledge Management Capability to Cope with Economic Disruption

53

the relationship between OL and OP. Their findings

indicated that the application of OL influences

company performance. Furthermore, Hanvanich et al.

(2006) suggested that learning and organisational

orientation memory is related to the output of an

organisation, not only when the company has various

levels of disruption in its environment but also when

the company has a similar level of environmental

turbulence. Ruiz-Mercader et al. (2006) emphasize

that individuals and OL show positive and significant

effects on OP. Thus, the next hypothesis is:

H

3

: Organisational Learning has a positive influence

on the Organization Performance

3.4 Relationship between

Organizational Learning (OL) and

Knowledge Management

Capability

Harvey et al. (2004) emphasised that one of main

organisational capabilities is ability to learn to adapt

to changing environments, both regionally and

dynamically. The purpose of an organization in the

learning process is to enhance managers’ and

employees’ ability in appliying the knowledge in

current era where information technology is

dominant. Theriou and Chatzoglou (2008) argue that

so that Knowledge Management (KM) and OL can be

more optimal in playing their roles that are somewhat

unique in creating organisational capabilities, which

leads to performance. Lee et al. (2007) in his research,

he proposed that learning ability and factor

knowledge ability are the source of a company’s

competitive advantage. Moreover, Currie and Kerrin

(2003) in their study adopted an OL perspective to

reflect more accurately the issues related to KM.

Previous research has shown a correlation between

OL and KMC, such as Theriou and Chatzoglou

(2008), Battor et al. (2008), and Sense (2007).

Therefore, the next hypothesis is as follows:

H

4

: Organizational Learning has a positive influence

on Knowledge Capability Management

Based on these hypotheses, researchers conducted

research using cross-sectional data to analyse the

various relationships between these variables.

4 METHODOLOGY

4.1 Population and Sample

The population in this study is the MSME sector in

Central Java. The MSME spreads in Central Java

region. This research applies SEM-PLS analysis. The

amount of the sample is 240 samples, assuming that

normality assumption is fulfilled and using Maximum

Likelihood Estimation (ML) technique (Sholihin &

Ratmono, 2013). The samples are SMEs businesses’

owners in Semarang, Pekalongan, Magelang and

Grobogan region.

4.2 Data Collection and Analysis

This study applies a structured and closed

questionnaire (Brace, 2004). The questionnaire

contains a series of statements which are carefully

arranged with a specific perspective to stimulate a

reliable response from the sample (Collis & Hussey,

2003). The statement in the questionnaire will be

measured using a Likert scale with a score of 1-5

(Brace, 2004). The sample unit is individual of

MSME business person in the regional area of Central

Java. Inferential analysis which will provide an

analysis of causal relationships between the

determinants (Ferdinand, 2006) in this study uses

SEM analysis with SEM-PLS software.

4.3 Reliability and Validity Test

The reliability and validity of the indicators in this

study will be tested using two methods, which are

convergent validity test and the discriminant validity

test (Ferdinand, 2006). The purpose of the reliability

and validity test is to verify whether the indicators

used are part of the construct and can be used to

measure the determinants (Byrne, 2010). Reliability

and validity tests on this indicator are also carried out

in order to test whether each construct or determinant

has special characteristics and the determinant is

reliable and can be used in a model (Ferdinand, 2006;

Santoso, 2010).

4.3.1 Structural Equation Model (SEM) Test

This section contains data analysis, relating to the

relationships between the variables in the model. Data

analysis will provide results and statistical analysis

whether there is a relationship between the variables

in the model.

Analysis of the data used in this study uses the

Structural Equation Model (SEM) approach with the

EBIC 2019 - Economics and Business International Conference 2019

54

SmartPLS 3.0 program. which consists of two stages,

the analysis of the outer model and the inner model.

Measurement Model Analysis (Outer Model)

a. Convergent Validity Test

The measurement model convergent validity test can

be analised based on the correlation between indicator

score with construct score (loading factor) with the

criteria for the loading factor of each indicator bigger

than 0.70. Furthermore, if the p-value <0.50, it is

considered as significant. Sholihin and Ratmono

(2013) explain that in some cases, newly developed

questionnaires is hard to reach loading factor value of

0.70. Therefore, base on the statement loading factors

between 0.40-0.70 must be considered to be

considered as valid.

Table 4.1: Convergent Validity

No. Determinant Indica

tor

Loadi

ng

factor

SE p

value

Valid/

Not

Valid

1 Entrepreneur

ial

Orientation

(EO)

X1 0.713 0.057 0.001 Valid

X2 0.649 0.058 0.001 Valid

X3 0.589 0.058 0.001 Valid

X4 0.805 0.056 0.001 Valid

X5 0.774 0.056 0.001 Valid

2 Organisation

al Learning

(OL)

X6 0.768 0.056 0.001 Valid

X7 0.757 0.057 0.001 Valid

X8 0.589 0.058 0.001 Valid

X9 0.770 0.056 0.001 Valid

X10 0.694 0.057 0.001 Valid

3 Organisation

al

Performance

(OP)

X11 0.821 0.056 0.001 Valid

X12 0.811 0.056 0.001 Valid

X13 0.868 0.055 0.001 Valid

X14 0.829 0.056 0.001 Valid

4 Knowledge

Management

Capability

(KCM)

X16 0.843 0.056 0.001 Valid

X17 0.849 0.056 0.001 Valid

X18 0.788 0.056 0.001 Valid

5 HEI

Engangemen

t

X19 0.903 0.055 0.001 Valid

X20 0.935 0.055 0.001 Valid

X21 0.881 0.055 0.001 Valid

Source: WarpPLS output

Discriminant validity is assessed based on cross-

loading measurements with determinants. There are

two ways to evaluate discriminant validity

requirement, the first is when construct correlation

with principal measurement (each indicator) is

greater than size of other constructs so it can be

concluded the discriminant is valid. The second is by

analysing discriminant validity with AVE criteria.

The criteria used are square roots of average variance

extracted (AVE), which is a diagonal column and

given parentheses must be higher than the correlation

between latent variables in the same column (top or

bottom).

The results of loading can be seen in table 4.2.

below:

Table 4.2. Laten construct output loading factor value

Indica

tor

Loadin

g

Factor

>

<

Factor loading value compare to

other constructs

Crit

eria

EO OL OP KC

M

HEI

X1 0.713 > -

0.193

-

0.204 0.115

-

0.032

Valid

X2 0.649 >

0.292

-

0.277 0.025

-

0.132

Valid

X3 0.589 > -

0.023

-

0.040 0.123 0.056

Valid

X4 0.805 > -

0.138 0.195

-

0.054 0.109

Valid

X5 0.774 >

0.095 0.247

-

0.165

-

0.017

Valid

X6 0.768 > -

0.314

0.073 0.164

-

0.120

Valid

X7 0.757 > -

0.137

-

0.223 0.077

-

0.001

Valid

X8 0.589 >

0.147

-

0.220

-

0.208

-

0.190

Valid

X9 0.770 >

0.215

0.236

-

0.072

-

0.160

Valid

X10 0.694 >

0.134

0.087

-

0.010 0.472

Valid

X11 0.821 >

0.041

-

0.122

-

0.054

-

0.161

Valid

X12 0.811 >

0.081

-

0.204

0.070

-

0.056

Valid

X13 0.868 > -

0.040

-

0.025

0.027 0.042

Valid

X14 0.829 > -

0.074 0.288

0.011 0.151

Valid

X16 0.843 >

0.090 0.070

-

0.042

-

0.125

Valid

X17 0.849 > -

0.046

-

0.182 0.141

-

0.086

Valid

X18 0.788 > -

0.047 0.121

-

0.107

0.226

Valid

X19 0.903 >

0.056 0.001

-

0.088 0.091

Valid

X20 0.935 > -

0.066

-

0.018 0.045 0.029

Valid

X21 0.881 >

0.012 0.019 0.043

-

0.124

Valid

Source: WarpPLS output

Based on the first stage of the above results, all

indicators have met the criteria for discriminant

SMES and HEI Collaboration: Improving SMEs’ Performance and Knowledge Management Capability to Cope with Economic Disruption

55

validity. Thus, it can be concluded that all indicators

have met the criteria for convergent validity. The

second method (AVE criteria), this method can be

done by evaluating the AVE criteria. AVE which is

in a diagonal column and given parentheses must be

higher than the correlation between latent variables in

the same column. Following AVE calculation results:

Table 4.3: Correlations among latent variables

EO OL OP KCM HEI

EO 0.710 0.618 0.606 0.596 0.456

OL 0.618 0.719 0.733 0.714 0.576

OP 0.606 0.733 0.752 0.563 0.551

KCM 0.596 0.714 0.563 0.827 0.578

HEI 0.456 0.576 0.551 0.578 0.906

Source: WarpPLS output

Table 4.3 shows the discriminant validity criteria

have been fulfilled indicated by the square root AVE

is greater than the correlation coefficient between

constructs on each variable.

b. Reliability Test Result

Table 4.4: Instrument reliability test Hasil Uji Reliabilitas

Instrumen

No. Variabel Composite

reliability

Criteria

1 EO 0.834 Reliabel

2 OL 0.841 Reliabel

3 OP 0.853 Reliabel

4 KCM 0.866 Reliabel

5 HEI 0.932 Reliabel

Source: WarpPLS output

Based on the table 4.4 it can be seen that the

reliability test results with the reliability composite

value of each variable used in this study are above

0.70, which means reliable.

Evaluation of Structural Model (Inner Model)

The next step is to conduct a structural evaluation

(inner model) which includes a model fit) path

coefficient test, and R

2

. Bsed on the WarpPls 3.0

analysis, the model fitness can be evaluate using

several criteria, as follows:

a. The average path coefficient (APC) has a p value

<0.05.

b. Average R-Squared (ARS) has a p value <0.05.

c. Average Block Variance Inflation (AVIF) has a

value <5; ideally 3.3.

The p values for APC and ARS are recommended

below 0.05 or significant. Furthermore, AVIF as an

indicator of multicollinearity is recommended has

lower value than 5. The output results indicate that

model goodness of fit model is fulfilled, the APC

value of 0.549 and ARS 0.517 and significant. AVIF

value of 1,802 also meets the criteria.

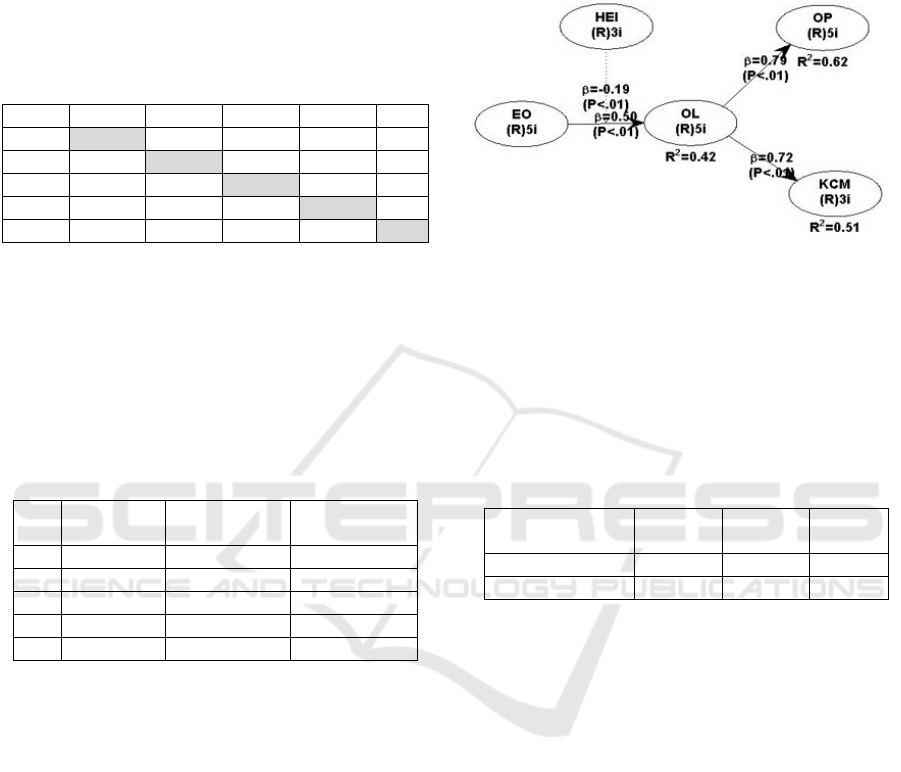

Figure 4.1. HEI-SME Structural Model

a. Direct Influence

This study applies table path coefficients to

commence hypothesis testing. The path coefficients

table which contains the values of t statistics and p-

values that shows the determinants relationships and

direction are provided in the table 4.6 below.

Table 4.5 Output Path Coefficients Model Direct Effect

Variabel EO-OL OL-OP OL-

KCM

Path Coefficients 0.502 0.788 0.716

P-Value 0.001 0.001 0.001

The independent variable at the 5% significance

level was declared significant as seen from the p-

value that was smaller than the alpha level that had

been set (α = 0.05). Based on Table 4.6. can be seen

the direct effect of this research model which can be

explained as follows:

Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) and

Organisational Learning (OL)

Table 4.5 shows that EO has a positive influence

(0.502) on OL and is significant with a p value of

0.001 (<0.05). The table shows that entrepreneurial

orientation has a significant positive effect on

organizational learning, so the first hypothesis that

formulates Entrepreneurial Orientation has a positive

effect on Organizational Learning is accepted.

Organisational Learning (OL) and Organisational

Performance (OP)

Table 4.5 shows that OL has a positive influence

(0.788) on OP and is significant with a p value of

EBIC 2019 - Economics and Business International Conference 2019

56

0.001 (<0.05). The table shows that organisational

learning has a significant positive effect on

organisational performance, so the third hypothesis

that formulates organizational learning has a positive

effect on organisational performance is accepted.

Organisational Learning (OL) and Knowledge

Management Capability (KM) Variables

Table 4.5. shows that OL has a positive influence

(0.716) on KMC and is significant with a p value of

0.001 (<0.05). The table explains that Organizational

Learning has a significant positive effect on

Knowledge Management Capability, so that fourth

hypothesis that formulates Organizational Learning

has a positive effect on Knowledge Management

Capability is accepted.

b. Test for Moderation Effect

Higher Education Institution (HEI) Engagement

moderates the relationship between EO and OL

variables. Table 4.6 shows the moderation effect of

Higher Education Institution (HEI) Engagement on

the relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation

and Organisational Learning.

Table 4.6: Moderation effect

Determinants EO-

OL

HEI*EO-

OL

OL-

OP

OL-

KCM

Path

Coefficients

0.502 -0.191 0.788 0.716

P-Value 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001

Source: WarpPLS output

The interaction coefficient of HEI * EO-OL (b =

-0.191; p = 0.001) indicates that Higher Education

Institution (HEI) Engagement weakens the

relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and

Organisational Learning. The higher the level of

Higher Education Institution (HEI) Engagement, the

lower the relationship between Entrepreneurial

Orientation and Organisational Learning. Likewise, if

the level of Higher Education Institution (HEI)

Engagement decrease, the relationship between the

two variables gets stronger. So, the second hypothesis

that formulates HEI engagement positively

moderates the relationship between EO and OL is

rejected.

5 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

This study has four hypotheses, the second hypothesis

is rejected, the discussion in this section provide in

depth analysis in HEI-MSMEs relationships.

Specifically, the moderating effect that has no

significance results.

Table 5.1: Hypotheses tests summary

Hypotheses Statement Result

H

1

Entrepreneurial

Orientation has positive

influence on

Organisational Learning

Accepted

H

2

HEI engagement

positively moderates the

relationship between EO

and OL

Rejected

H

3

Organisational Learning

has a positive influence

on the Organisation

Performance

Accepted

H

4

Organisational Learning

has a positive influence

on the Organisation

Performance

Accepted

5.1 Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO)

and Organisational Learning (OL)

Based on the data analysis, the results show that

Entrepreneurial Orientation has a positive influence

on Organisational Learning, this result is in line with

previous studies conducted by several previous

researchers (Chaston et al., 2001; Dess et al., 2003;

Ashforth et al., 2007); by implementing EO, the

company will have a better market position to obtain

and combine the knowledge needed. In addition, the

study commenced by Dess et al. (2003) argued that

companies that develop knowledge through EO or

entrepreneurial orientation are able to form an

effective corporation, namely in form of uniqueness

such as innovation. Chaston et al. (2001) in their

research emphasised that companies or institutions

that adopt Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) based on

their market position to offer their products in form of

innovative goods and services, are expected to

increase higher level of Organizational Learning

(OL). Further evidence shows that companies with

high EO levels will actively seek new knowledge.

This idea is reinforced by research conducted by

Ashforth et al. (2007) which emphasised an argument

that the proactive behavior contained in EO can

facilitate the learning process carried out by a

company. EO has pertinent role in enable companies

to accommodate learning process. Moreover, by

applying proper EO will provide companies with

SMES and HEI Collaboration: Improving SMEs’ Performance and Knowledge Management Capability to Cope with Economic Disruption

57

more willingness to learn and attempt for better

knowledge understandings.

5.2 Higher Education Institution (HEI)

Engagement Moderates the

Relationship between EO and OL

Variables

The results of data analysis showed that

Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organisational

Learning variables were not positively moderated by

Higher Education Institutional Engagement variable.

The results show that a coefficient of -0.19 means that

HEI Engagement weakens the EO and OL

relationships.This is in contrast with the results of

research conducted by several experts such as Baba et

al., 2009; Wiklund, et al., 2009; Huggins et al., 2008;

Sanzo et al., 2012; Philbin, 2012 and Wilson, 2012.

They stated that: MSMEs have limited resources,

because of those resources, MSMEs need to access a

variety of resources, including knowledge. Using a

resource perspective, such companies can use

network resources, such as some MSMEs that have a

network with higher education institutions

(universities), to gain knowledge (Wiklund et al.,

2009) and to build additional network-based

knowledge with another organization. Previous

research has emphasised that the role of relationship-

based variables has and is the basis and special

relevance in the relationship between companies and

higher education institutions (Sanzo et al., 2012). In

addition, universities are a source of strength in the

knowledge-based economy of the twenty-first

century (Wilson, 2012: 2) so that involvement

between SMEs and universities is very important to

support growth and development. Previous research

also has found that joint research between companies

and universities, as a means of growing engagement

and commitment, has a large impact that allows a

company to access various resources (Huggins et al.,

2008). The forms of services offered and provided by

higher education institutions such as universities to

small companies include various types of business

assistance, such as: extension services, and

accelerator and outreach programs designed to

transfer academic expertise in the form of the latest

technology and business practices to improve product

performance, product quality, and process efficiency

(Huggins et al., 2008). The relationship between

higher education institutions and industry has become

a popular mindset or direction of knowledge today,

where academics act as suppliers of knowledge

through university-industry collaboration that

encourages learning interactions in gaining

knowledge (Baba et al., 2009). Philbin (2012)

suggested that university involvement will bridge the

learning process, university collaboration with

business is a form of alliance that provides a

foundation for learning. Furthermore, companies that

collaborate with higher education institutions gain

access to specific knowledge that in the future can be

further developed to improve the competitiveness of

the industry or the company itself (Philbin, 2012).

This research obtains different results. It is

possible that there are some ineffective programs

provided by HEI or higher education institutions.

Another cause is the possibility that in the application

of accompanying, the assistance carried out so far has

not been carried out by an effective measurement of

impact to the MSME businesses. Furthermore, the

results do not support the opinions of some of the

experts above are also caused by the ability of the

absorption of science and especially innovative ideas

provided by higher education institutions (Cohen &

Levinthal, 2000).

5.3 Relationship between

Organizational Learning (OL) and

Organizational Performance (OP)

Organisational Learning has a positive influence on

Organisational Performance, these results support a

study which is commenced by Huber (1998) which

confirms that OL increases the ability of a business

organisation to innovate, which in turn can have an

impact on improving competitiveness and

organisational performance. Yang et al. (2007)

provided a more thorough assessment of the

relationship between OL and OP. Their findings

indicated that the application of OL influences

company performance. Hanvanich et al. (2006)

suggested that learning orientation and organisational

memory are related to the outcomes of an

organization, not only when companies have different

levels of disruption in their environment but also

when companies have similar levels of environmental

disruptions. Ruiz-Mercader et al. (2006) emphasised

that individuals and OL show positive and significant

effects on OP. Theriou and Chatzoglou (2008) also

suggested that knowledge management (KM) and OL

play a focal role in creating organisational

capabilities, which leads to good performance.

Furthermore, Rhodes et al. (2008) stated that OL has

positive relationship with innovation process in

Indonesia in form of knowledge transfer to improve

company performance-organisational performance

(OP).

EBIC 2019 - Economics and Business International Conference 2019

58

5.4 Organisational Learning and

Knowledge Management

Capability Variables

The results of the data analysis concluded that

Organizational Learning (OL)has a positive influence

on Knowledge Management Capability (KM), these

results support previous research by Theriou and

Chatzoglou (2008), Battor et al. (2008), and Sense

(2007). Furthermore, these study also supports

Harvey et al. (2004) which emphasised that one of

main organisational capabilities is ability to learn and

to adapt to regional and global environment

disruptions. The benefit of a learning process in an

organisation is to improve its managers’ and

employees’ ability in knowledge application in

present information technology era. Theriou and

Chatzoglou (2008) argued that Knowledge

Management (KM) and OL can be optimised in

playing their roles in creating organisational unique

capabilities, which leads to performance. Lee et al.

(2007) in his research stated that ability to learn and

ability of knowledge factors are the source of a

company's competitive advantage. Currie and Kerrin

(2003) in their study adopted an OL perspective to

reflect more accurately the issues related to KM.

6 CONCLUSION AND FURTHER

RESEARCH

From the results of data analysis several conclusions

can be drawn as follows:

1. Entrepreneurial Orientation has a positive

influence on Organisational Learning.

2. Higher Education Institutional Engagement does

not moderate the positive Relationship between

Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organisational

Learning.

3. Organisational Learning has a positive influence

on Organizational Performance.

4. Organisational Learning has a positive influence

on Knowledge Management Capability.

FURTHER RESEARCH

As researchers we are aware that this research still has

some weaknesses, such as the geographical coverage

of existing respondents, there is also probability that

respondents have never experienced innovation and

knowledge from existing higher education

institutions or there is also possibility that they have

not been able to captivate knowledge and innovation.

Further research is suggested to be able to provide

a clearer picture of the role of higher education

institutions in the MSME sector in Central Java, as

well as the need to be more optimal in identifying

areas that have or have not been touched by the active

involvement of higher education institutions.

REFERENCES

Anatan L (2013) A proposed framework of university to

industry knowledge transfer. Review of Integrative

Business and Economics Research 2(2): 304–325.

Ahlström-Söderling, R. (2003). SME strategic business

networks seen as learning organizations. Journal of

Small Business and Enterprise Development, 10(4),

444-454.

Asad Sadi, M., & Henderson, J. C. (2011). Franchising and

small medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in

industrializing economies: A Saudi Arabian

perspective. Journal of Management Development,

30(4), 402-412.

Ashforth, B. E., Sluss, D. M., & Saks, A. M. (2007).

Socialization tactics, proactive behavior, and newcomer

learning: Integrating socialization models. Journal of

vocational behavior, 70(3), 447-462.

Baba Y, Shichijo N and Sedita SR (2009) How do

collaborations with universities affect firms’ innovative

performance? The role of ‘Pasteur scientists’ in the

advanced materials field. Research Policy 38(5): 756–

764.

Battor, M., Zairi, M. and Francis, A. (2008), “Knowledge-

based capabilities and their impact onperformance: a

best practice management evaluation”, Business

Strategy Series, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 47-56.

BIS (2012) Following up the Wilson review of business-

university collaboration: Next steps for universities,

business and governments. Available at:

http://bis.ecgroup.net/Publications/HigherEducation/

HEStrategyReports.aspx

Bosworth, G. (2009). Education, mobility and rural

business development. Journal of Small Business and

Enterprise Development, 16(4), 660-677.

Carson, D., Gilmore, A., & Rocks, S. (2004). SME

marketing networking: a strategic approach. Strategic

Change, 13(7), 369-382.

Charles, D. (2006). Universities as key knowledge

infrastructures in regional innovation systems.

Innovation: the European journal of social science

research, 19(1), 117-130.

Chaston, I., & Mangles, T. (2000). Business networks:

assisting knowledge management and competence

acquisition within UK manufacturing firms. Journal of

Small Business and Enterprise Development, 7(2), 160-

170.

SMES and HEI Collaboration: Improving SMEs’ Performance and Knowledge Management Capability to Cope with Economic Disruption

59

Chaston I, Badger B and Sadler-Smith E (2001)

Organizational learning: An empirical assessment of

process in small U.K. manufacturing firms. Journal of

Small Business Management 39(2): 139–151.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (2000). Absorptive

capacity: A new perspective on learning and

innovation. In Strategic Learning in a Knowledge

economy (pp. 39-67).

Currie, G. and Kerrin, M. (2003), “Human resource

management and knowledge management:enhancing

knowledge sharing in a pharmaceutical company”,

International Journal ofHuman Resource Management,

Vol. 14 No. 6, pp. 1027-45.

De La Maza-Y-Aramburu, X., Vendrell-Herrero, F., &

Wilson, J. R. (2012). Where is the value of cluster

associations for SMEs?. Intangible Capital, 8(2), 472-

496.

Decter, M., Bennett, D., & Leseure, M. (2007). University

to business technology transfer—UK and USA

comparisons. Technovation, 27(3), 145-155.

Dess GG, Ireland RD, Zahra SA, et al. (2003) Emerging

issues in corporate entrepreneurship. Journal

ofManagement 29: 351–378.

Gibbs, R.,Humphries, Andrew. (2009). Strategic Alliances

and Marketing Partnerships: gaining competitive

advantage through collaboration and partnering. Kogan

Page Publishers.

Gilmore, A., Carson, D., & Grant, K. (2001). SME

marketing in practice. Marketing intelligence &

planning, 19(1), 6-11.

Grant, R. M., & Baden‐Fuller, C. (2004). A knowledge

accessing theory of strategic alliances. Journal of

Management Studies, 41(1), 61-84.

Gunasekara, C. (2006). Reframing the role of universities

in the development of regional innovation systems. The

Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(1), 101-113.

Guston, D. H. (2000). Retiring the social contract for

science. Issues in science and technology, 16(4), 32.

Hsu, T. H., & Tang, J. W. (2010). A model of marketing

strategic alliances to develop long-term relationships

for retailing. The International Journal of Business and

Information, 5(2), 151-172.

Huber, G.P. (1998), “Synergies between organizational

learning and creativity and innovation”,Creativity and

Innovation Management, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 3-8.

Huggins R, Johnston A and Steffenson R (2008)

Universities, knowledge networks and regional

policy.Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and

Society 1: 321–340.

International Trade Centre (ITC), 2015, SME

Competitiveness Outlook 2015: Connect, Compete and

Change for Inclusive Growth,Geneva: ITC, 2015. xxx,

235 pages.

Jämsä, P., Tähtinen, J., Ryan, A., & Pallari, M. (2011).

Sustainable SMEs network utilization: the case of food

enterprises. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise

Development, 18(1), 141-156.

Kadam, A., & Ayarekar, S. (2014). Impact of Social Media

on Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Performance:

Special Reference to Small and Medium Scale

Enterprises. SIES Journal of Management, 10(1).

Lambooy, J. (2004). The transmission of knowledge,

emerging networks, and the role of universities: an

evolutionary approach. European Planning Studies,

12(5), 643-657.

Lowensberg, D. A. (2010). A “new” view on “traditional”

strategic alliances' formation paradigms. Management

Decision, 48(7), 1090-1102.

Macpherson, A., & Holt, R. (2007). Knowledge, learning

and small firm growth: a systematic review of the

evidence. Research Policy, 36(2), 172-192.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., & Nagata, A. (2000). A firm as a

knowledge-creating entity: a new perspective on the

theory of the firm. Industrial and corporate change,

9(1), 1-20.

Plazibat, I., & Filipović, D., 2010, Strategic alliances as

source of retailers competitive advantage. In Fifth

International Conference''Economic Development

Perspectives of SEE Region in Global Recession

Context''.

Petkovska, T. (2015). The Role and Importance of

Innovation in Business of Small and Medium

Enterprises. Economic Development/Ekonomiski

Razvoj, 17.

Peças, P., & Henriques, E. (2006). Best practices of

collaboration between university and industrial SMEs.

Benchmarking: An International Journal, 13(1/2), 54-

67.

Philbin SP (2012) Resource-based view of university-

industry research collaboration. In: Proceedings of the

Portland International Center for Management of

Engineering and Technology (PICMET), Vancouver,

BC, Canada, 29 July–2 August, pp.400–411. New

York: IEEE.

Priyambodo, RH, 2016, Pekerja harus mengantisipasi

dengan memiliki kompetensi yang bisa diserap oleh

lapangan kerja.", Antara, 2016.

Radek, 2015, Potensi UKM di Komunitas Pasar Asean,

Disnakertrans-Edisi SDM-Oktober,2015.

Sanzo MJ, Santos ML, Garcia N, et al. (2012) Trust as a

moderator of the relationship between organizational

learning and marketing capabilities: Evidence from

Spanish SMEs. International Small Business Journal

30(6): 700–726.

Sense, A.J. (2007), “Stimulating situated learning within

projects: personalizing the flow of knowledge”,

Knowledge Management Research & Practice, Vol. 5

No. 1, pp. 13-21.

Sholihin,M., Ratmono,Dwi., (2013), “Analisis SEM-PLS

dengN WarpPLS 3.0 untuk Hubungan Nonlinier dalam

Penelitian Sosial dan Bisnis, Penerbit ANDI,

Yogyakarta.

Stanworth, J., Purdy, D., English, W., & Willems, J. (2001).

Unravelling the evidence on franchise system

survivability. Enterprise and Innovation Management

Studies, 2(1), 49-64.

Street, C. T., & Cameron, A. F. (2007). External

relationships and the small business: A review of small

EBIC 2019 - Economics and Business International Conference 2019

60

business alliance and network research*. Journal of

Small Business Management, 45(2), 239-266.

Sudarmiatin, 2011, Franchising Business Practice In

Indonesia, Business Opportunity and Investment,

Pidato Pengukuhan Guru Besar sebagai Guru Besar

dalam Bidang Ilmu Manajemen 39 pada Fakultas

Ekonomi (FE) UM, Kamis, 28 April 2011, Malang

State University, Indonesia

Susilo, Y. (2012). Strategi Meningkatkan Daya Saing

UMKM Dalam Menghadapi Implementasi CAFTA dan

MEA. Buletin Ekonomi.

Tedjasuksmana, B. (2014). Potret UMKM Indonesia

Menghadapi Masyarakat Ekonomi ASEAN 2015.

Theriou, G.N. and Chatzoglou, P.D. (2008), “Enhancing

performance through best HRM practices,

organizational learning and knowledge management: a

conceptual framework”, European Business Review,

Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 185-207.

Todeva, E., & Knoke, D. (2005). Strategic alliances and

models of collaboration. Management Decision, 43(1),

123-148.

Tödtling, F., & Kaufmann, A. (2001). The role of the region

for innovation activities of SMEs. European Urban and

Regional Studies, 8(3), 203-215.

Vargo, J., & Seville, E. (2011). Crisis strategic planning for

SMEs: finding the silver lining. International journal of

production research, 49(18), 5619-5635.

Wiklund J, Patzelt H and Shepherd D (2009) Building an

integrative model of small business growth. Small

Business Economics 32: 351–374.

Wilson T (2012) A review of business–university

collaboration. Available at: http://bis.ecgroup.net/

Publications/HigherEducation/HEStrategyReports.asp

x

SMES and HEI Collaboration: Improving SMEs’ Performance and Knowledge Management Capability to Cope with Economic Disruption

61