Market Reaction on Reverse Stock Split Announcement: Empirical

Evidence in Indonesian Stock Market

Edwin Hendra, Theresia Lesmana, and Sasya Sabrina

Accounting Department, Bina Nusantara University, Jl. K.H. Syahdan No. 9, Palmerah, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Event Study, Reverse Stock Split, Insider Trading

Abstract: This research focuses on reverse stock split announcements. We are trying to examine stock returns behavior

on days prior and following the reverse split announcements. The sample of this study is reverse stock split

events on an Indonesian stock market within the year of 2002-2018. An earlier abnormal stock price

movement before the announcement shows a sign of insider trading existences, and a delayed abnormal stock

price movement following the announcement shows a slow respond of market reaction to particular new

information. We are using cumulative abnormal return (CAR) and cumulative market-adjusted return

(CMAR) to identify the abnormal stock price movement. The results show that there are positive abnormal

returns before the announcement, and then it declines further into negative abnormal returns until post the

announcement. However, when we segregate the sample into four price fractions, we find positive abnormal

returns patterns only appear on two-five thousand rupiahs price fraction. Meanwhile, the other price fraction

categories show declining patterns of negative abnormal returns. Overall, we temporarily suggest that there

are illegal insider trading activities in the Indonesian Stock Market. The immediate market reactions show

that the market is quite efficient, and its responses regarding the reverse stock split event follow the prediction

of the trading range hypothesis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Reverse stock split (reverse split) is a less popular

corporate action relative to a regular (forward) stock

split. The literature has frequently discussed stock

splits across periods and equity markets of countries.

However, the reverse splits have not received many

interests in the academic community since the first

studies by (Fama et al., 1969). The reverse split is a

technical merging number of outstanding shares to

form a smaller number of proportionally higher-

priced shares. Since it is supposed to be purely

cosmetic, theoretically, the reverse split should not

affect future cash flows nor the total value of the

company.

Nevertheless, many studies show mostly negative

market reactions to the stock price following reverse

split announcement (Woolridge and Chambers, 1983;

Lamoureux and Poon, 1987; Peterson and Peterson,

1992; Hwang, 1995; Desai and Jain, 1997).

Following the efficient market hypothesis (Fama,

1969)—the stock price will react to new information.

Thus, the public considers reverse split

announcement as unfavorable information of a firm.

There are three theories—signaling hypothesis,

trading range hypothesis, and liquidity hypothesis,

that may explain what kind of information conveyed

by a stock split announcement, which causes a market

reaction. The signaling hypothesis posits that the

firm’s management wants to convey favorable private

information about the firm’s prospect and therefore

signals undervaluation of the splitting firms (Brennan

and Copeland, 1988; Byun and Rozeff, 2003). The

trading range hypothesis posits that the stock split is

an instant attempt to put the stock price back on an

optimal trading range, which is preferable to investors

(Copeland, 1979; Ikenberry, Rankine, and Stice,

1996; Amihud, Mendelson and Uno, 1999). The

liquidity hypothesis posits that the stock split is an

attempt to increase the liquidity or trading volume,

which in turn increases its split-adjusted price

(Muscarella and Vetsuypens, 1996; Lin, Singh, and

Yu, 2009). For the reverse split cases, trading range

hypothesis is a more suitable explanation, since

usually managers are forced to do a reverse split

rather than do it deliberately (Peterson and Peterson,

1992; Martell and Webb, 2008).

Since stock splits usually convey favorable

information about the firms, thus positive abnormal

154

Hendra, E., Lesmana, T. and Sabrina, S.

Market Reaction on Reverse Stock Split Announcement: Empirical Evidence in Indonesian Stock Market.

DOI: 10.5220/0009200601540161

In Proceedings of the 2nd Economics and Business International Conference (EBIC 2019) - Economics and Business in Industrial Revolution 4.0, pages 154-161

ISBN: 978-989-758-498-5

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

returns, particularly those coming shortly before a

split’s announcement date, should raise strong

suspicions of insider trading, particularly in nations

with weak regulatory structures (Nguyen, Tran, and

Zeckhauser, 2017). The insider traders may exploit

the leakage of information by buying shares of

splitting firms few days before a split’s

announcement is going public, where it may cause a

sudden increase in the stock prices during that period.

On the contrary, if the insider trader also exists in

reverse split events, then hypothetically, there will be

negative abnormal returns on days before reverse

split’s announcements since the reverse splits are

considered conveying unfavorable information.

Indonesia is one of developing countries with

“adolescence” stock market, yet has excellent growth

potential, and characterized by nonsynchronous

trading, where shares of some listed firms are rarely

traded or not traded at all during a specific period.

Reverse splits in Indonesia stock market usually are

conducted by less big listed firms, which it has

nonsynchronous trading characteristic and rarely

becomes the object of studies. Since Indonesia is one

of the emerging markets, then we can assume that the

Indonesian stock market has no strong regulatory

structure. Thus it may be threatened by some illegal

trading activities.

In this paper, we conduct an event study of reverse

split events in Indonesia stock market. We are trying

to identify the stock price behavior of reverse splitting

firms by analyzing whether there are abnormal

returns during the event window—30 days prior and

30 days post the announcement date. The abnormal

returns before the announcement date may indicate

that there were illegal trading activities. On the other

hand, the abnormal returns post the announcement

date shows a market inefficiency due to the

information delay. Lastly, since reverse splits are

rarely become the object of studies, we hope that our

findings may give a significant contribution to the

reverse split event study literature, particularly in the

emerging market context.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Reverse splits are desperate efforts by the firms to

raise their prices high enough to meet the minimum

price required to maintain a listing on the stock

exchange (Martell and Webb, 2008). Sixty-five

percent of the firms with multiple reverse splits end

up being liquidated or delisted. If one reverse split is

a sign of desperation, then multiple reverse splits are

a sign of extreme distress (Crutchley and Swidler,

2015). Reverse split announcements are interpreted as

unfavorable information of the firm because the

manager is considered do not have any other ways to

raise the stock price, thus it results in a negative effect

on the stock returns that happened both on the

announcement date and the effective date of the

reverse splits (Woolridge and Chambers, 1983). The

further researches find negative abnormal returns

since the announcement date of reverse splits, which

continued to accumulate in the short term (Hwang,

1995) and also in the long term (Desai and Jain,

1997).

The signaling hypothesis posits that the abnormal

returns during the stock split show a signal from the

firm’s management that conveys favorable private

information about the firm’s prospects (Brennan and

Copeland, 1988). The increasing stock prices after the

split are followed by increased future dividends that

assume the firms had better performance (Fama et al.,

1969). Splitting firms yield higher earnings growth

than similar, non-splitting firms in the five years

before the split (Lakonishok and Lev, 1987).

Nevertheless, stock splits that are not followed by a

subsequent abnormal return in the long term period

show that the market is efficient (Byun and Rozeff,

2003). In reverse split cases, the signaling hypothesis

is not applicable because it is improbable the manager

would do a deliberate reverse split just to let the

public knows that the price stock is somewhat

overvalued.

The trading range hypothesis suggests that there

is an optimal trading range, and that splits realign

share prices. At the optimal trading range, the stock

will be more frequently traded and get become more

attractive to the investors. Stock splits generally occur

when stocks trade at high prices preceding the split

announcement, which is consistent with the view that

splits are typically used to realign share prices to an

average trading range (Ikenberry, Rankine, and Stice,

1996). Meanwhile, firms do a reverse split is to

increase the marketability of their stocks because the

market will consider a stock with too lower price as a

penny stock, which is speculative and less attractive,

particularly to the institutional investors (Peterson

and Peterson, 1992).

The liquidity hypothesis posits that stock splits

may improve trading continuity, alleviate liquidity

risk and give more benefit to the less liquid stocks

(Lin, Singh and Yu, 2009). A reduction in the

minimum trading unit greatly increases a firm’s base

of individual investors and its stock liquidity, and it is

associated with a significant increase in the stock

price (Amihud, Mendelson and Uno, 1999). Copeland

(1979) shows that there were increasing trading

volume following the stock splits, but not increased

proportionally to its split factor. The increasing

liquidity following the stock split may reduce the

liquidity risk and cause the split-adjusted stock price

to increase substantially. On the contrary, there is a

Market Reaction on Reverse Stock Split Announcement: Empirical Evidence in Indonesian Stock Market

155

possibility the liquidity risk will be decreased

following the reverse split, so that it may cause the

split-adjusted stock price to decrease. Nevertheless, it

would be very unlikely that decreasing liquidity

becomes the ulterior motive behind the reverse split.

Insider trader—the corporate insider who has

more direct access to firm wellbeing, may exploit

their informational advantage about the company to

gain unfair profit from trading activities. In most

nations, it is considered as illegal activities if the trade

was made based on non-public material information.

However, illegal trading is much harder to be studied,

given that perpetrators try to hide their tracks and that

broadly effective detection methods are not available.

Nevertheless, some existing studies have creatively

detected evidence of illegal trades. Bhattacharya,

Daouk, Jorgenson, and Kehr (2000) suggest the

researcher be suspicious of illegal trading activity if

there is nothing happened during the day of the

corporate action announcement and something

happened during the days before the pre-

announcement. Cheng, Nagar, and Rajan (2007)

suggest that the corporate insider has misused the

delay of legal insider trading disclosure to perform

information-based trading.

Nguyen et al. (2017) find that there are incredibly

high abnormal returns and increasing trading volume

before the split announcement, which may indicate

illegal trading activities in the Vietnam stock market.

We suggest that the Indonesian stock market probably

has a weak regulatory structure since it is also one of

the emerging markets as well as Vietnam.

Hypothesis 1: There are earlier abnormal returns

before the reverse split announcement as an

indication of illegal trading activities.

Unlike the regular stock split, successful firms that

receive much attention from the market is unlikely to

conduct a reverse split. On the contrary, it is usually

quite popular among less attractive firms. Thus, we

suggest that the market will react slowly to an

announcement made by this kind of company.

Hypothesis 2: There are delayed abnormal returns

post to the reverse split announcement as an

indication of market inefficiency.

The reverse split theoretically is more in line with the

trading range hypothesis instead of the two others.

The literature mentions that the primary purposes of

the reverse split are fulfilling the listing requirement

(Martell and Webb, 2008) and avoiding the penny

stock label (Peterson and Peterson, 1992). Thus, we

suggest that the market will favor the reverse split

announcement by showing positive abnormal returns.

On the other hand, the literature has documented

empirical evidence of negative market reactions

following reverse split announcements (Woolridge

and Chambers, 1983; Lamoureux and Poon, 1987;

Peterson and Peterson, 1992; Hwang, 1995; Desai

and Jain, 1997).

Hypothesis 3: There are unpredicted abnormal

return patterns following reverse split

announcements.

3 METHOD

We analyze 60 days stock return data—30 days prior

and 30 days post to the reverse split announcement—

as the event window. The sample is stocks listed on

the Indonesia Stock Exchange in the year 2002 to

2018. There were 49 reverse split events during those

years, but due to the limitation of data, we can only

observe 44 split events as the research sample. The

stock split announcement dates are derived from

KSEI’s (Kustodian Sentral Efek Indonesia) official

website. The stock prices and market index are

gathered from the Thomson Reuters Data Stream.

The daily stock return and market return are

calculated using a simple stock return formula, as in

equation (1) and (2).

𝑅

𝑃

𝑃

𝑃

(1)

𝑅

𝐼𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑥

𝐼𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑥

𝐼𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑥

(2)

We were using two kinds of abnormal return

measurements—Cumulative Market Adjusted Return

(CMAR) and Cumulative Abnormal Return (CAR)—

to analyze the market reaction during the event

window as in equation (3) and (4).

𝐶𝑀𝐴𝑅

,

1𝑅

𝑅

1

(3)

𝐶𝐴𝑅

,

𝑅

𝛼

𝛽

𝑅

(4)

We measure the alpha and beta of each stock

using the single index model in equation (5) by

regressing 250 daily returns before the event window.

𝑅

𝛼

𝛽

𝑅

𝑢

(5)

We analyze the univariate test—using SPSS 24

statistic software—for hypothesis testing. We use the

one-sample t-test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in

EBIC 2019 - Economics and Business International Conference 2019

156

identifying whether abnormal return and cumulative

abnormal return are significantly different from zero

and not normally distributed during a particular event

day.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 shows the detail of the reverse stock split

announcement sample. The reverse stock split events

most frequently happened during the year of 2002 –

2005 and becoming less frequent in years after, with

the most commonly chosen split factor are between

1:4 and 1:10.

Table 1. Reverse Stock Split Announcement Sample

Year Split Factor

1:2 1:4-

6

1:8-

10

1:15-

25

1:100 Tot

al

02-05 2 4 10 4 1 21

06-10 4 5 1 1 - 11

11-14 - 1 2 1 - 4

15-18 - 2 5 - 1 8

Total 6 12 18 6 2 44

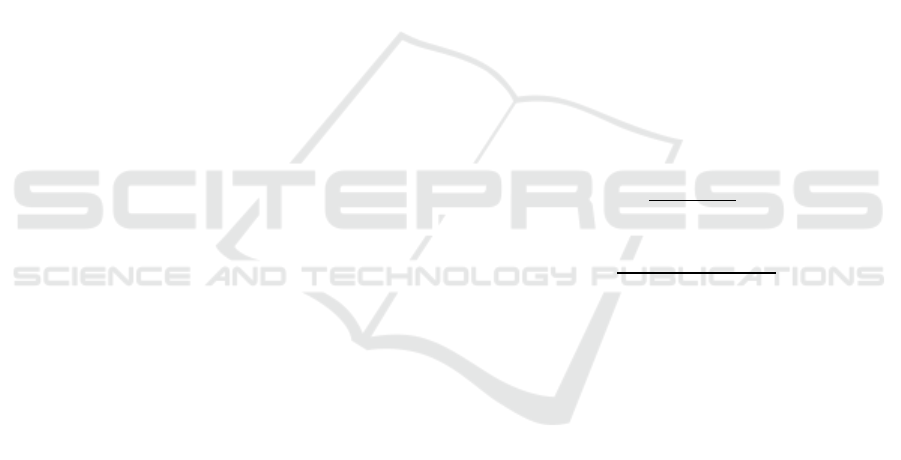

Figure 1 shows the average and median of CAR

of the reverse stock split events. Both graphs show a

similar pattern that the CAR is increasing since day t-

30, and it starts to decline after day t-20. After the

announcements, the CAR is dropping further and

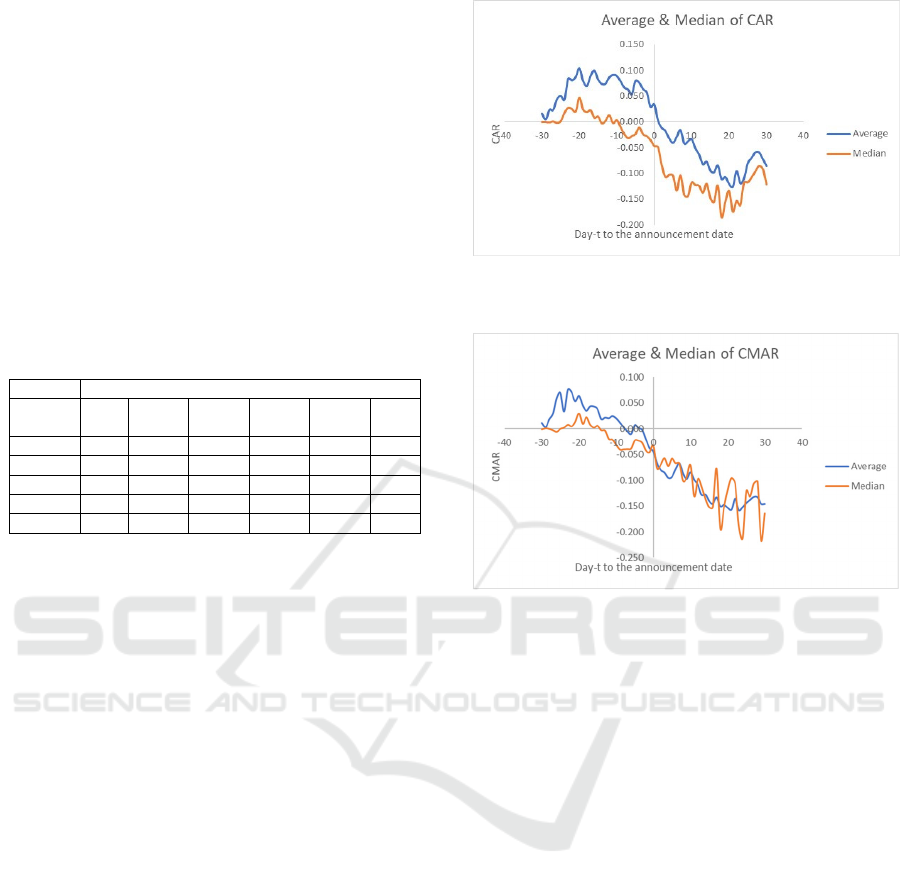

begins to rebound on day t+20. Figure 2 shows the

average and median of CMAR of the reverse stock

split events. The graphs of CMAR tell a similar story,

but it already shows indications of negative abnormal

return before the announcements.

Table 2 and Table 3 show the descriptive statistics

of CAR and CMAR on the event window. We only

use 36 reverse split events on CAR calculation, since

we could not estimate the coefficient regression of the

single index model due to the inactive transaction of

the stocks during the estimation period. One Sample

t-test shows a significantly positive result on CAR

and CMAR on the day t-20. Meanwhile, the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test shows a significant result

for all day before the announcement for both CAR

and CMAR. On the one hand, the average CAR on

the days before the announcement shows a positive

sign. On the other hand, the median CAR, average

CMAR, and median CMAR have already reversed

the sign to be negative before the announcement day.

Figure 1: Average CAR and Median CAR of Reverse Split

Events

Figure 2: Average CMAR and Median CMAR of Reverse

Split Events

CAR and CMAR show a declining pattern post of

the announcement day. For the CAR, the one-sample

t-tests do not show any significant result. Meanwhile,

the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests show a significant

result at least for ten days post to the announcement

day. On the contrary, the one-sample t-tests show a

longer-term significance on CMAR, while the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests provide similar results in

comparison with CAR. According to these findings,

on the averages, our results support the first

hypothesis rather than the second hypothesis.

Just like a regular stock split, a reverse split is also

not just a purely cosmetic. These findings provide

evidence that the reverse splits convey specific

information. Our results in line with the previous

literature (Woolridge and Chambers, 1983;

Lamoureux and Poon, 1987; Peterson and Peterson,

1992; Hwang, 1995; Desai and Jain, 1997) that the

market reacts negatively on the stock prices following

the reverse split announcement. These reactions are

immediate following the announcement. Thus, we

may suggest that the Indonesian stock market is quite

efficient regarding this matter.

Market Reaction on Reverse Stock Split Announcement: Empirical Evidence in Indonesian Stock Market

157

Table 2: Cross-sectional Average and Median of CAR and

CMAR Between Day -30 and Day 0

Day-

t

CAR CMAR

Average Median Average Median

-30 0.016 0.000

***

0.012

-0.002

***

-29 0.005 0.000

***

0.003 0.001

***

-28 0.024 -0.001

***

0.018 -0.001

***

-27 0.023 0.001

***

0.030 -0.003

***

-26 0.044 -0.002

***

0.060 -0.006

***

-25 0.051 0.001

***

0.071 -0.001

***

-24 0.043 0.017

***

0.034 0.002

***

-23 0.084 0.027

***

0.076 0.008

***

-22 0.081 0.025

***

0.071 0.004

***

-21 0.088 0.020

***

0.053 0.013

***

-20 0.104

*

0.047

***

0.064

*

0.029

***

-19 0.080 0.024

***

0.046 0.009

***

-18 0.070 0.019

***

0.036 0.022

***

-17 0.089 0.022

***

0.044 0.008

***

-16 0.100 0.008

***

0.044 0.002

***

-15 0.082 0.010

***

0.039 0.006

***

-14 0.074 -0.003

***

0.019 -0.003

***

-13 0.074 0.002

***

0.022 -0.004

***

-12 0.087 0.013

***

0.021 -0.020

***

-11 0.091 -0.003

***

0.025 -0.021

***

-10 0.089 0.003

***

0.021 -0.031

***

-9 0.079 -0.010

***

0.012 -0.040

***

-8 0.067 -0.024

***

0.004 -0.040

***

-7 0.063 -0.032

***

-0.004 -0.039

***

-6 0.054 -0.028

***

-0.010 -0.038

***

-5 0.079 -0.024

***

0.008 -0.023

***

-4 0.076 -0.011

***

0.002 -0.023

***

-3 0.064 -0.024

***

-0.002 -0.027

***

-2 0.057 -0.028

***

-0.020 -0.042

***

-1 0.029 -0.035

***

-0.037 -0.046

***

0 0.034 -0.047

***

-0.043 -0.033

***

Notes: *, **, and *** denote statistically different than zero

at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively for one-sample t-

test (on the average column) and one-sample Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test (on the median column)

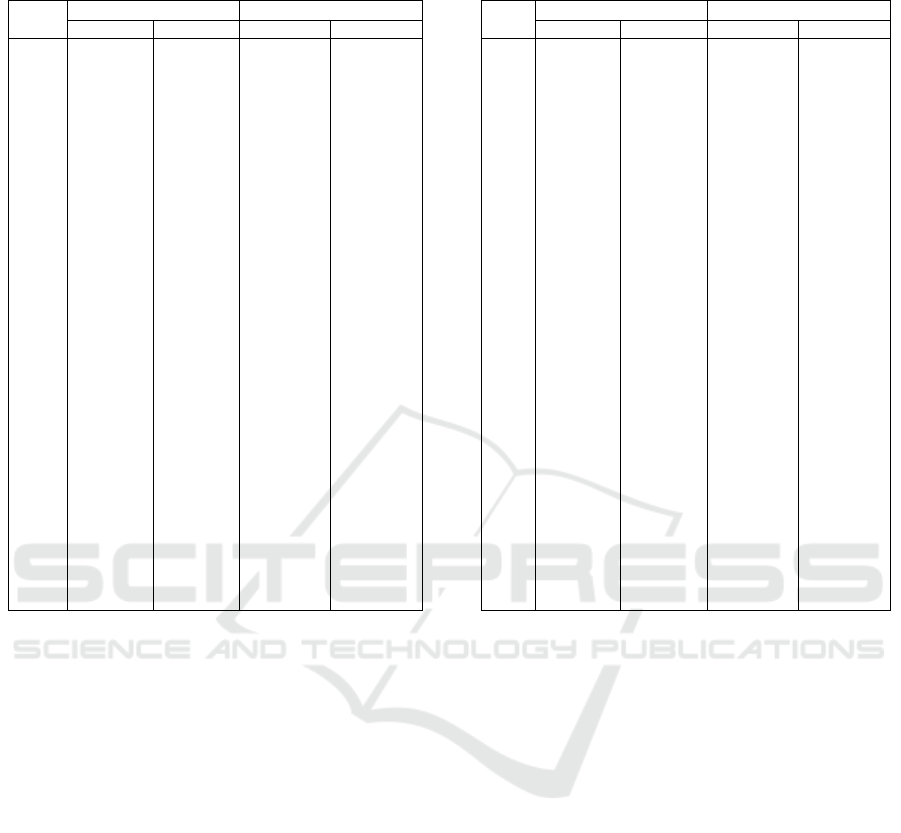

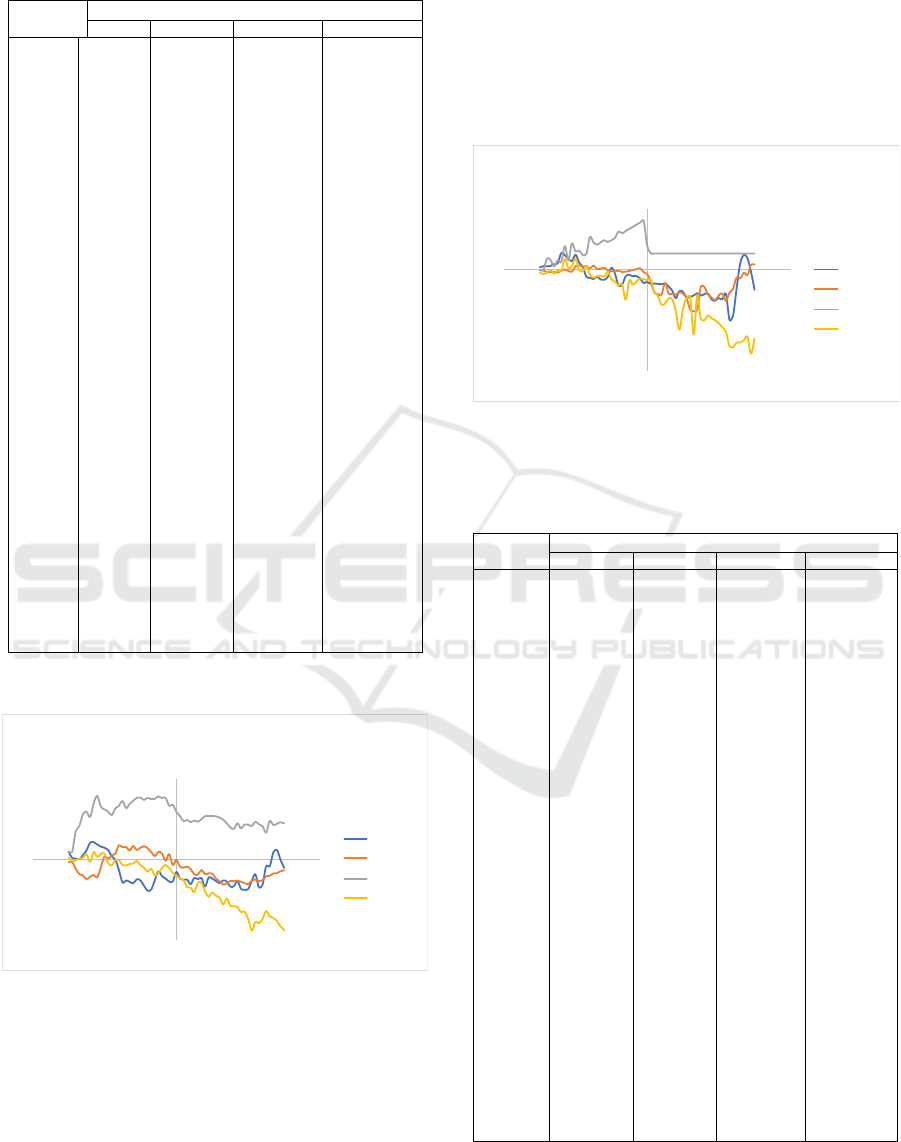

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the average and the

median of CAR, on various expected stock price

faction after the reverse split is executed—day 0 price

times the split factor. We arbitrarily determine the

nominal price classification just based on the current

BEI’s price fraction for regular trading. The nominal

price fraction of two thousand until five thousand

rupiahs has a positive value in the average and the

median of CAR for the whole event window periods.

Meanwhile, the other price fractions show a negative

value with a declining pattern, whereas the price

fraction above five thousand rupiahs has the most

extreme declining.

Table 3: Cross-sectional Average and Median of CAR and

CMAR Between Day 0 and Day +30

Day-

t

CAR CMAR

Average Median Average Median

0 0.034 -0.047

***

-0.043 -0.033

***

1 0.002 -0.049

***

-0.067 -0.078

***

2 -0.011 -0.083

***

-0.080

*

-0.069

**

3 -0.017 -0.107

***

-0.085

**

-0.057

***

4 -0.032 -0.102

***

-0.095

**

-0.072

***

5 -0.041 -0.104

**

-0.093

**

-0.058

***

6 -0.029 -0.133

**

-0.078 -0.067

***

7 -0.016 -0.103

**

-0.066 -0.067

**

8 -0.042 -0.141

*

-0.087

*

-0.102

***

9 -0.038 -0.144

*

-0.097

**

-0.093

*

10 -0.033 -0.118

**

-0.084

*

-0.070

**

11 -0.051 -0.122 -0.099

*

-0.132

**

12 -0.064 -0.124 -0.109

**

-0.097

**

13 -0.082 -0.137 -0.128

**

-0.112

14 -0.077 -0.120 -0.127

**

-0.136

15 -0.095 -0.147 -0.140

***

-0.152

16 -0.098 -0.155 -0.145

***

-0.153

17 -0.084 -0.123 -0.133

***

-0.078

**

18 -0.111 -0.184 -0.150

***

-0.194

19 -0.107 -0.155 -0.147

***

-0.153

20 -0.120 -0.133 -0.153

***

-0.119

21 -0.126 -0.173 -0.157

***

-0.095

22 -0.095 -0.153 -0.135

**

-0.106

23 -0.119 -0.161 -0.158

***

-0.188

24 -0.110 -0.118 -0.152

***

-0.213

25 -0.080 -0.117 -0.143

**

-0.120

26 -0.070 -0.108 -0.138

**

-0.132

**

27 -0.059 -0.096 -0.132

**

-0.107

28 -0.059 -0.085 -0.133

**

-0.102

29 -0.072 -0.091 -0.145

**

-0.217

30 -0.086 -0.121 -0.145

**

-0.164

Notes: *, **, and *** denote statistically different than zero

at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively for one-sample t-

test (on the average column) and one-sample Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test (on the median column)

Table 4 and Table 5 show a cross-sectional

average of CAR on each price fraction category

during the event window. One-sample t-test shows a

weakly significantly positive CAR on a few days

before the announcement for the two-five thousand

rupiahs price fraction. On the contrary, there is a

significantly negative CAR on days post the

announcement for the above five thousand rupiahs

price fraction.

Table 6 and Table 7 show a cross-sectional

median of CAR on each price fraction category

during the event window. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

shows significant results only for the days before the

announcement. The results are entirely consistent,

that positively significant CAR is found on two-five

thousand rupiahs price fraction, while negatively

significant CAR is found on the other price fractions.

Thus, overall, our findings support the third

hypothesis.

EBIC 2019 - Economics and Business International Conference 2019

158

Table 4: Cross-sectional Average of CAR on Expected

Stock Price Fraction Between Day -30 and Day 0

Day-t

CAR

<500 500-1999 2000-4999 >5000

-30 0.047 -0.017 0.048 0.008

-29 0.008 -0.015 0.047 -0.014

-28 0.005 -0.057

*

0.175 -0.007

-27 0.000 -0.089 0.209 0.002

-26 0.026 -0.098

*

0.282 0.007

-25 0.055 -0.121 0.298 0.030

-24 0.102

*

-0.106 0.265 -0.018

-23 0.106

*

-0.095 0.349 0.044

-22 0.091

*

-0.110 0.395

*

0.013

-21 0.078 -0.047 0.327

*

0.033

-20 0.072 0.019 0.312 0.033

-19 0.059 0.005 0.298 -0.025

-18 0.018 0.023 0.276 -0.039

-17 -0.002 0.035 0.318 -0.006

-16 -0.067 0.088 0.334

*

-0.007

-15 -0.144 0.075 0.363

*

-0.038

-14 -0.132 0.078 0.319

*

-0.040

-13 -0.140 0.056 0.346

*

-0.030

-12 -0.150 0.083 0.364

*

-0.028

-11 -0.125 0.058 0.382

*

-0.011

-10 -0.132 0.074 0.386

*

-0.038

-9 -0.165 0.082 0.370

*

-0.053

-8 -0.196 0.070 0.383

*

-0.080

-7 -0.189 0.046 0.375

*

-0.060

-6 -0.131 0.021 0.376

*

-0.103

-5 -0.076 0.048 0.392

*

-0.087

-4 -0.105 0.037 0.381

*

-0.056

-3 -0.121 -0.008 0.383

*

-0.037

-2 -0.139 0.035 0.334 -0.058

-1 -0.138 -0.034 0.341 -0.086

0 -0.079 -0.002 0.297 -0.105

Notes: *, **, and *** denote statistically different than zero

at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively for one sample t-

test.

Figure 3: Average CAR of Each Expected Stock Price

Fractions

Our findings are also in line with the trading range

hypothesis and liquidity hypothesis. We temporarily

suggest that the nominal price in between two

thousand and five thousand rupiahs is the optimal

trading range. Thus the market reacts positively to the

reverse split attempts to put the nominal stock price

in that ranges (Ikenberry, Rankine, and Stice, 1996).

On the other hand, within the context of reverse split,

we temporarily suggest that the market still considers

the stock traded below two thousand rupiahs as a

penny stock (Peterson and Peterson, 1992) and the

stock traded above five thousand rupiahs will become

further less liquid (Amihud, Mendelson and Uno,

1999; Lin, Singh and Yu, 2009). Therefore, the

market reacts negatively to these categories of the

reverse split.

Figure 4: Median CAR of Each Expected Stock Price

Fractions

Table 5: Cross-sectional Average of CAR on Expected

Stock Price Fraction Between Day 0 and Day +30

Day-t

CAR

<500 500-1999 2000-4999 >5000

0 0.047 -0.017 0.048 0.008

1 0.008 -0.015 0.047 -0.014

2 0.005 -0.057 0.175 -0.007

3 0.000 -0.089 0.209 0.002

*

4 0.026 -0.098 0.282 0.007

*

5 0.055 -0.121 0.298 0.030

*

6 0.102 -0.106 0.265 -0.018

*

7 0.106 -0.095 0.349 0.044

*

8 0.091 -0.110 0.395 0.013

**

9 0.078 -0.047 0.327 0.033

**

10 0.072 0.019 0.312 0.033

**

11 0.059 0.005 0.298 -0.025

*

12 0.018 0.023 0.276 -0.039

*

13 -0.002 0.035 0.318 -0.006

**

14 -0.067 0.088 0.334 -0.007

*

15 -0.144 0.075 0.363 -0.038

**

16 -0.132 0.078 0.319 -0.040

**

17 -0.140 0.056 0.346 -0.030

**

18 -0.150 0.083 0.364 -0.028

**

19 -0.125 0.058 0.382 -0.011

**

20 -0.132 0.074 0.386 -0.038

**

21 -0.165 0.082 0.370 -0.053

**

22 -0.196 0.070 0.383 -0.080

**

23 -0.189 0.046 0.375 -0.060

**

24 -0.131 0.021 0.376 -0.103

**

25 -0.076 0.048 0.392 -0.087

**

26 -0.105 0.037 0.381 -0.056

***

27 -0.121 -0.008 0.383 -0.037

**

28 -0.139 0.035 0.334 -0.058

**

29 -0.138 -0.034 0.341 -0.086

**

30 -0.079 -0.002 0.297 -0.105

**

Notes: *, **, and *** denote statistically different than zero

at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively for one sample t-

test.

‐0.500

‐0.400

‐0.300

‐0.200

‐0.100

0.000

0.100

0.200

0.300

0.400

0.500

‐40‐30‐20‐100 10203040

CAR

Day‐ttotheannocementdate

AverageCARofEachExpectedStockPrice

Fractions

<500

500‐1999

2000‐4999

>5000

‐0.5

‐0.4

‐0.3

‐0.2

‐0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

‐40‐30‐20‐10 0 10 20 30 40

CAR

Day‐ttotheannocementdate

MedianCARonofEachExpectedStockPrice

Fractions

≤500

500‐1999

2000‐4999

≥5000

Market Reaction on Reverse Stock Split Announcement: Empirical Evidence in Indonesian Stock Market

159

Table 6: Cross-sectional Median of CAR on Expected

Stock Price Fraction Between Day -30 and Day 0

Day-t

CAR

<500 500-1999 2000-4999 >5000

-30

0.013

**

-0.001

***

0.001

***

-0.013

**

-29

0.019 -0.002

***

0.001

***

-0.019

-28

0.017

**

-0.010

**

0.057

***

-0.013

-27

0.020

**

-0.009

***

0.050

***

0.000

-26

0.028 -0.010

**

0.018

***

-0.017

*

-25

0.033 -0.012

***

0.048

***

-0.001

**

-24

0.084 -0.003

***

0.039

***

-0.004

*

-23

0.073 0.004

***

0.119

**

0.057

-22

0.056 -0.003

**

0.048

***

0.009

-21

0.043 -0.007 0.134

**

0.021

-20

0.076 0.021 0.092

**

0.058

-19

0.036 0.024 0.097

**

-0.001

***

-18

0.015 0.017 0.074

*

-0.005

-17

-0.034 0.021

***

0.080

**

0.021

-16

-0.040 0.008

***

0.166 -0.021

*

-15

-0.046 0.024

**

0.138 -0.037

-14

-0.033

***

0.005

**

0.126 -0.029

-13

-0.048 0.007 0.138

*

-0.027

-12

-0.049 0.013

**

0.149 -0.032

-11

-0.034

**

-0.001

*

0.140 -0.009

**

-10

0.011

*

-0.005

*

0.148 -0.045

-9

-0.018

*

-0.006

**

0.160 -0.055

-8

-0.078

*

-0.003

*

0.192 -0.078

**

-7

-0.074

*

-0.009 0.183 -0.069

**

-6

-0.031 -0.007

**

0.195 -0.147

-5

-0.024 -0.004 0.205 -0.050

-4

-0.032 0.000 0.215 -0.072

-3

-0.030 0.005 0.226 -0.056

-2

-0.042

*

0.010 0.236 -0.042

-1

-0.065 -0.009 0.247 -0.044

0

-0.060 -0.019 0.121 -0.049

Notes: *, **, and *** denote statistically different than zero

at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively for Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The reverse split announcement events are responded

well in the Indonesian stock market, even though it

was a less popular corporate event conducted by less

popular firms. It shows that the Indonesian stock

market is quite efficient. The declining pattern of

cumulative abnormal returns shows that the market

sees the reverse split events as a negative signal, and

we find our results are consistent with the previous

literature. The early market reactions on several days

before the announcement may indicate the existence

of illegal insider trading activities. These reactions

may be various, but we find that it may depend on the

expected stock price after the reverse split is

Table 7: Cross-sectional Median of CAR on Expected

Stock Price Fraction Between Day -30 and Day 0

Day-t

CAR

<500 500-1999 2000-4999 >5000

0

-0.060

-0.019 0.121 -0.049

1

-0.070 -0.056 0.083 -0.046

2

-0.068 -0.112 0.083 -0.109

3

-0.070 -0.118 0.083 -0.128

4

-0.071 -0.123 0.083 -0.172

5

-0.067 -0.062 0.083 -0.166

6

-0.083 -0.117 0.083 -0.140

7

-0.102 -0.117 0.083 -0.143

8

-0.141 -0.122 0.083 -0.203

9

-0.104 -0.108 0.083 -0.296

10

-0.109 -0.116 0.083 -0.193

11

-0.136 -0.139 0.083 -0.139

12

-0.134 -0.196 0.083 -0.130

13

-0.127 -0.204 0.083 -0.319

14

-0.116 -0.201 0.083 -0.122

15

-0.127 -0.080 0.083 -0.243

16

-0.120 -0.083 0.083 -0.249

17

-0.118 -0.123 0.083 -0.224

18

-0.147 -0.136 0.083 -0.240

19

-0.153 -0.150 0.083 -0.248

20

-0.140 -0.125 0.083 -0.263

21

-0.146 -0.116 0.083 -0.284

22

-0.119 -0.153 0.083 -0.305

23

-0.250 -0.111 0.083 -0.379

24

-0.228 -0.094 0.083 -0.383

25

-0.092 -0.036 0.083 -0.360

26

0.032 -0.041 0.083 -0.360

27

0.075 -0.013 0.083 -0.349

28

0.059 -0.025 0.083 -0.331

29

-0.010 0.027 0.083 -0.416

30

-0.099 0.027 0.083 -0.339

Notes: *, **, and *** denote statistically different than zero

at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively for Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test.

executed. The positive abnormal returns average on

certain price fraction, particularly between two

thousand and five thousand rupiahs, show that there

is an optimal trading price as predicted by the trading-

range hypothesis. Meanwhile, the declining pattern of

negative abnormal returns on the above five thousand

rupiahs price fraction is consistent with the liquidity

hypothesis’ prediction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge that the present

research is assisted by Tita Nuvita from Institut Bisnis

Nusantara and Arfan Wiraguna from Prasetya Mulya

University in the data processing and supported

EBIC 2019 - Economics and Business International Conference 2019

160

financially by the 2019 research grant of Bina

Nusantara University.

REFERENCES

Amihud, Y., Mendelson, H. and Uno, J. (1999) ‘Number of

shareholders and stock prices: Evidence from Japan’,

Journal of Finance, 54(3), pp. 1169–1184.

Bhattacharya, U. et al. (2000) ‘When an event is not an

event: The curious case of an emerging market’,

Journal of Financial Economics, 55(1), pp. 69–101.

Brennan, M. J. and Copeland, T. E. (1988) ‘Stock splits,

stock prices, and transaction costs’, Journal of

Financial Economics, pp. 83–101.

Byun, J. and Rozeff, M. S. (2003) ‘Long-Run performance

after stock splits: 1927 to 1996’, Journal of Finance,

58(3), pp. 1063–1085.

Cheng, S., Nagar, V. and Rajan, M. V. (2007) ‘Insider

trades and private information: The special case of

delayed-disclosure trades’, Review of Financial

Studies, 20(6), pp. 1833–1864.

Copeland, T. E. (1979) ‘Liquidity changes following stock

split’, Journal of Finance, 34(1), pp. 115–141.

Crutchley, C. E. and Swidler, S. (2015) ‘Multiple reverse

stock splits (investors beware!)’, Journal of Economics

and Finance, 39(2), pp. 357–369.

Desai, H. and Jain, P. C. (1997) ‘Long‐run common stock

returns following stock splits and reverse splits’, The

Journal of Business, 70(3), pp. 409–433.

Fama, E. F. (1969) ‘Efficient capital markets: A review of

theory and empirical work’, Journal of Finance, 25(2),

pp. 383–417.

Fama, E. F. et al. (1969) ‘The Adjustment of Stock Prices

to New Information’, International Economic Review,

10(1), pp. 1–21.

Hwang, C. Y. (1995) ‘Microstructure and reverse stock

splits’, Review of Quantitative Finance and

Accounting, 5(2), pp. 169–177.

Ikenberry, D. L., Rankine, G. and Stice, E. K. (1996) ‘What

do stock splits realy signal’, Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis, 31(3), pp. 357–375.

Lakonishok, J. and Lev, B. (1987) ‘Stock splits and stock

dividends: Why, who, and when’, Journal of Finance,

42(4), pp. 913–932.

Lamoureux, C. G. and Poon, P. (1987) ‘The market reaction

to stock splits’, Journal of Finance, 42(5), pp. 1347–

1370.

Lin, J. C., Singh, A. K. and Yu, W. (2009) ‘Stock splits,

trading continuity, and the cost of equity capital’,

Journal of Financial Economics, 93(3), pp. 474–489.

Martell, T. F. and Webb, G. P. (2008) ‘The performance of

stocks that are reverse split’, Review of Quantitative

Finance and Accounting, 30(3), pp. 253–279.

Muscarella, C. J. and Vetsuypens, M. R. (1996) ‘Stock

splits: Signaling or liquidity? The case of ADR “solo-

splits”’, Journal of Financial Economics, 42(1), pp. 3–

26.

Nguyen, V., Tran, A. and Zeckhauser, R. (2017) ‘Stock

splits to profit insider trading: Lessons from an

emerging market’, Journal of International Money and

Finance, 74(1), pp. 69–87.

Peterson, D. R. and Peterson, P. P. (1992) ‘A further

understanding of stock distributions: The case of

reverse stock splits’, Journal of Financial Research,

15(3), pp. 189–205.

Woolridge, J. R. and Chambers, D. R. (1983) ‘Reverse

splits and shareholder wealth’, Financial Management,

12(3), pp. 5–15.

Market Reaction on Reverse Stock Split Announcement: Empirical Evidence in Indonesian Stock Market

161