Perception and Reality of Corruption: A Spatiotemporal Analysis

in Indonesia Sub-national Level

Zuhairan Yunmi Yunan

Ph.D. Candidate at the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling

University of Canberra, Australia

Keywords: Corruption Patterns, Spatial Distribution, Regional Perception Indicators, A Judicial Report

Abstract: This paper employs regional perception and judicial report of corruption to investigate the patterns of

corruption at districts and municipalities level in Indonesia. To describe the distribution of the existing data,

spatial distribution has been utilized supported by the correlation for each measurement. Spatiotemporal

analysis has been used to see changes among regions or overtimes. The number of corruption incidents and

state financial loss increased significantly in Indonesia while the perception is showing a better condition

against corruption. The comparison among regions shows the perceptions toward the level of corruption tend

to be higher in the region, which has fewer incidents of corruption. However, corruption perceptions tend to

improve when corruption incidents/value increase in one particular region, indicating the effectiveness of

judicial systems enhances business sectors' perception of corruption over time. The main lesson highlighted

from this paper is the necessity for regional corruption measurement to explain corruption patterns in

Indonesia.

1 INTRODUCTION

Corruption is extraordinary and unique since it is hard

to determine the right victims afflicted by corruption.

The objective data are difficult to obtain, and to date,

all existing approaches have not yet described the

actual level of corruption. The measurement of

corruption should be emphasized that there is no

general agreement on corruption definition in the

world that ultimately affects the level of corruption in

each country (Johnston, 1996, 2002, 2010; Jain, 2001;

Kurer, 2005; Brown, 2006; Miller, 2006; Philp,

2006). Many factors that cause corruption are very

difficult to define or measure. Besides, it is hidden

activities; the acceptance of corruption is different

based on variations in culture, law, customs

(Svensson, 2005). In addition, the definition of

corruption in either explicitly or comprehensively is

not clearly explained by the United Nation

Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). Therefore,

measuring the real corruption is exceptionally

challenging as it is an essential part for analyzing the

impact of corruption that can be used to design

corruption eradication policy.

The debate on corruption measurement is very

interesting among economists since corruption has an

impact on economic variables and vice versa.

Although it is impossible to measure real corruption

(Johnston and Kpundeh, 2002), some scholars claim

that measuring corruption is reasonable since

monitoring corruption can be done through various

approaches and indicators in either subjective or

objective, aggregate or disaggregate, cross as well as

the single country (Kaufmann, 2005; Kaufmann,

Kraay and Mastruzzi, 2007). There are some reasons

why it is important to measure this phenomenon.

First, it is essential to figure out the problem scale

since what it is dealing with can be recognized

(Belousova, Goel, and Korhonen, 2016). Second, to

see whether there are any clear patterns to identify

explanatory variables that explains why and where

corruption developed (Mauro, 1995). Third,

corruption measurement can help policymakers

where they need to take any actions and examine

whether it has been effective or not (Rose and

Mishler, 2010; Bohn, 2012; Gutmann, Padovano and

Voigt, 2015).

In general, the explanation of corruption

measurement can be narrated by dividing it into four

possible approaches, i.e., perception indicators,

surveys, indirect and outcome indicators (Kenny,

2009), judicial system reports (Bhargava and

220

Yunan, Z.

Perception and Reality of Corruption: A Spatiotemporal Analysis in Indonesia Sub-national Level.

DOI: 10.5220/0009402202200228

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity (ICOACI 2019), pages 220-228

ISBN: 978-989-758-461-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Bolongaita, 2004; Del Monte and Papagni, 2007).

Although corruption is a part of criminal activities, it

is difficult to find the studies describing the pattern of

corruption by regional mapping using those

approaches.

In the context of Indonesia, since the system of

governance has changed to decentralization after a

massive protest in reformation 1998, much of the

government authorities have been transferred to the

district level, and the corruption pattern has changed

from centralized (Mcleod, 2000) to be spread to the

regional level. However, studies on corruption in

Indonesia have not discussed how the pattern of

corruption in this era. The country that has more than

17,000 islands with diverse cultures and languages, it

is likely that corruption level is varied in a different

area of the country. Current measurements are not

able to describe the level of corruption in the regional

context (districts or municipalities). Therefore, it is

important to know how the level of corruption in each

area in Indonesia. Consequently, understanding

corruption in Indonesia requires investigation at its

regional level.

This paper provides information on how the

pattern of corruption in Indonesia's districts and

municipalities has been changed since

decentralization. Following this, it is structured into

four sections. In the second section, it elaborates a

literature review discussing corruption definition, the

concept of perception indicators as well as judicial

system reports, and spatiotemporal analysis in the

context of a criminal issue. Data and method applied

to analyze this paper are explained in the third

section. Findings of this research are written in the

fourth section discussing the international approach

on corruption measurement, the distribution of

judicial report on corruption, regional perception, and

reality on corruption. The fifth section presents the

conclusion as well as contribution and

recommendation for future empirical studies on

corruption measurement in Indonesia region.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Corruption Definition

Understanding of corruption literature is very varied.

Corruption can be defined from many perspectives

such as religious, law, sociology, politics, and even

economics. Some institutions and scholars can also

explain corruption definition. However, the definition

of corruption in this study focuses on economic

thought. It is believed that addressing definition early

in this paper is essential to develop strong academic

arguments regarding corruption terminology. The

discussions of corruption definition become an

important issue because it provides more pertinent

information for measuring corruption.

Some institutions give the definition of

corruption. Although United Nations Convention

against Corruption (UNCAC) as a world institution

which focuses on corruption issues does not define

precisely about its context since corrupt behavior

differs one and another (United Nations, 2004), others

define corruption in almost the same meaning. For

instance, World Bank implies that corruption is an act

of influencing other people whether directly or

indirectly in an inappropriate manner while

Transparency International defines corruption as the

misuse of public power for private profit or the

misuse of entrusted power for private gain. As for

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and

Development (OECD) does not have a specific

definition about corruption; however, they set up a

range of corrupt behavior as mentioned in UNCAC

such as influencing on trading, bribing public

officials whether domestic or international,

obstruction of justice, embezzlement. Likewise,

International Monetary Fund (IMF) concludes the

definition from several institutions is becoming "the

abuse of public office for private gain," and it is

included whether financial gains or not (IMF, 2017).

Among scholars, the spreading of corruption

definition is still highly debated and not agreed yet

(Mikkelsen, 2013). The concept of corruption was

traditionally restricted to the destruction of integrity

in the discharge of public duties (Theobald, 1990).

The definition of corruption usually associated with

public officials and the performance of public duties

influenced by bribery. However, it is now

increasingly accepted that the act of corruption may

apply to both public and private individuals and may

extend beyond bribery (Ng, 2006).

Wedeman (2004) stated that corruption includes

bribery, embezzlement, concealment, and laundering

of proceeds, and trading in influence. Corruption is

not about manipulation only, but it is also related to

cronyism, money politics, bribery, and gratification.

It has been classified as administrative and legislative

corruption. However, understanding of corruption is

closely related to the norms and conventions of its

original state because the limitation of the definition

of corruption is still difficult to determine even

though the term corruption is very easy to understand

by many people (Kurer, 2005).

In Indonesia context; however, the view and

definition of corruption have been shifting as well as

Perception and Reality of Corruption: A Spatiotemporal Analysis in Indonesia Sub-national Level

221

judicial processes (Butt, 2012). Finding a national

consensus on corruption definition is necessary.

There is no consensus about corruption definition in

either among scholars as well as international

organizations. However, corruption is closely related

to the norms and conventions of its original state

(Kurer, 2005). Hence, this paper uses the definition of

corruption based on Indonesian corruption

eradication act. No. 20 of 2001 on the changes in law

No. 31 of 1999.

In a juridical sense, the definition of corruption is

not only limited to the actions of public officials that

cause state financial loss but also includes the actions

is detrimental to individual or public. Such as Bribery,

both active (bribing) and passive (bribed);

Embezzlement; Extortion; Trading in influence;

Gratification; and Fraud. Accordingly, the

understanding of corruption measurement in this

paper is in-line with the definition of corruption

referred.

2.2 Corruption Perception Indicator

Scholars interested in the complex phenomenon of

corruption have been trying to measure corruption,

although the issues over the definition of corruption

remain unsettled. Initially, the efforts were based on

obtaining objective measurements such as a number

of asserts and convictions for corruption, counts of

newspaper stories on corruption, and other official

records and statistics. In this approach, it is hard to

define whether the criminal justice system (anti-

corruption agencies, prosecutors, and judges) are

effective or not. Meanwhile, in highly corrupt

countries, the media has not had an important role in

reporting serious corruption.

Over the past 30 years, the efforts to proxy

corruption as valid and reliable data have been more

developed by academicians, the international

organization, as well as non-government organization

using subjective measure developed perception and

experience-based measures. It has been derived from

a range of surveys, business and expert assessments

based on their experiences to corruption, for instance,

whether they have been offered as well as received or

given a bribe in a country.

The most perception indicators commonly used to

see the level of corruption across the world and have

become established as cited indicator for the

economics of corruption research is the Corruption

Perception Index (CPI). The data has been published

by Transparency International (a non-governmental

organization based in Berlin dedicated to raising

public awareness about the severity of the global

corruption problem). First released in 1995, the CPI

has quickly become the best known of corruption

measurement tools. The CPI is a composite index (a

survey of surveys) that draws on existing global

expert evaluations and business opinion surveys from

a variety of third party sources, including commercial

risk rating agencies, think tanks, NGOs, and

international organizations. It provides information

about corruption from administrative and political

aspects around the world yearly according to the

perceived level of public sector corruption as

determined by experts, business people, and analysts

(Heinrich and Hodess, 2011).

Since Transparency International first released,

the CPI has quickly become the best-known

corruption indicator worldwide. This index has been

broadly used by many scholars to measure corruption

in every country level as well as compare and analyze

cross-countries' level of corruption. From the first

publication, the CPI’s score countries are from 1 to

10 scale, where 0 represents the most corrupt while

10 represents the least corrupt. However, from 2012

until now, the scale has changed becoming on a zero-

to-hundred. The CPI has been widely credited with

making a comparative and large number of studies of

corruption possible, as well as putting the issue of

corruption squarely in the international policy

agenda. Despite its enormous influence on both

academic and policy fronts, the CPI is not without

critics. One often noted critique is that the CPI relies

solely on surveys of foreign businesspeople and the

expert assessments of cross-national analysis; as

such, the CPI mainly reflects international experts'

perceptions, not the perceptions of each country's

citizens.

Although perception measurement is more stable

across time and it represents the quality of institutions

(Kenny, 2009), these are much different from actual

occurrence and real corruption level (Treisman, 2007;

Rose and Peiffer, 2012). For control of corruption

indices, business elites could give bias information

when describing corruption since they have political

interest (Rohwer, 2009).

In addition, Malito (2014) has particularly

emphasized evaluating perception indicators to the

three matters. First, there are biases in subjective data

since the perception avoids the absolute amount of

corruption. Second, the technique of aggregating

multiple data may be risked. The third is the problem

of gathering and missing data since for some

indicators, and it affects the researcher to reach other

information without considering about aggregation.

Internal validity could be low because the indices

depend on different sources for most of the years.

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

222

Andersson & Heywood (2009) state that those indices

have created a "corruption trap"; however, it is widely

recognized that perception-based measure has

contributed to the efforts of corruption eradication

agenda through promoting good governance system.

According to the explanation above, although CPI

has some benefits to see the level of corruption in

Indonesia and the source of data received from

various Indonesia region, it is very difficult to analyze

deeper about corruption in sub-national level.

Therefore, it is imperative that regional perception-

based should be considered in either from the

municipality or district level.

3 DATA AND METHOD

3.1 Data

This paper employs two approaches as indicators to

measure corruption in Indonesia. First, it is a

subjective approach using the Corruption Perception

Index (CPI) data issued by Transparency

International Indonesia. Second, the data on

corruption cases are legally binding from the

Supreme Court, which is an objective approach. CPI

itself is only available in the 4-year period (2004,

2006, 2008, 2010) using a scale from 0 to 10 (0 is

highly corrupt, and 10 is very clean). For 2004, it

covers 26 cities/districts in Indonesia, while 2006

becomes 37 cities/districts. Whereas the coverage

area in 2008 and 2010 are 55 cities/districts.

Corruption cases data are from 2001 to 2014,

which are divided into two types. First, the number of

corruption cases indicated by the number of

perpetrators, and second, the value of state losses due

to corruption. During the data period, the number of

corruption cases was 3050 spread across 230 districts

and 64 cities, while the total of state financial loss was

USD8.1 Billion. This research uses 294

districts/municipalities as a spatial unit based on the

1996 version from the number of

districts/municipalities in Indonesia. Since the

decentralization era, the latest consistent region in

Indonesia can be used to analyze spatial distribution

is in 1996. All region that has divided after

decentralization will be re-adjust to the number of

regions in 1996.

3.2 Method

To describe the distribution of the existing data,

spatial distribution has been utilized supported by the

correlation for each measurement of corruption that

has been used to see the relationship between regional

CPI and judicial report data. Spatiotemporal analysis

has been employed to see changes among regions or

overtimes. Since corruption is a part of crime issue,

spatiotemporal is used to see understanding location

and connectivity through interaction when incidence

at the same time close in regional space (Jacquez,

1996; Kulldorff and Hjalmars, 1999), and regular

occurrence in the timing and spacing (Bowers and

Johnson, 2005; Sagovsky and Johnson, 2007).

Further understand the characteristic of the region

(Block and Block, 1995; Brantingham, P. L.

Brantingham, 1999; Loukaitou-sideris, 1999).

Likewise, an increase or decrease of corruption level

in an area over time can be approached using this

method which as it is done by (Grubesic and Mack,

2008) in analyzing crime trend.

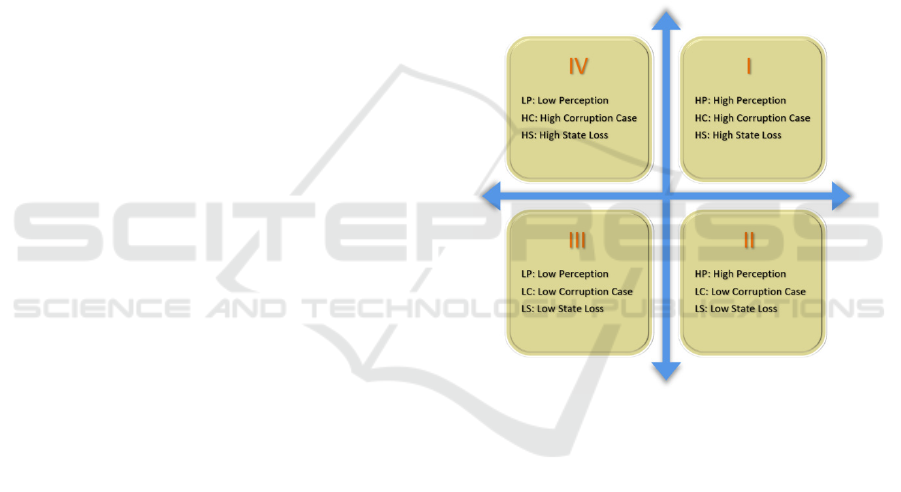

Figure 1: Corruption perception (x-axis) and corruption

reality (y-axis) quadrant.

To get more understanding about those

connections, this paper has divided and grouped the

area with the same patterns into four quadrants (see

figure 1). In general, regions that have a high

perception of corruption, the number of corruption

cases and their state financial loss are low (quadrant

II), and vice versa (quadrant IV). It means that there

is a negative relationship between perception and the

incident of corruption.

Perception and Reality of Corruption: A Spatiotemporal Analysis in Indonesia Sub-national Level

223

4 FINDINGS

4.1 An International Approach to

Corruption Measurement

The result shows that the country's perception of

corruption tends to improve and positively related to

the number of corruption cases handled in Indonesia.

It indicates that the more corruption cases treated, the

perception index will increase over time. The trend

between national CPI, regional CPI, and state

financial loss have the same pattern as well. Table 1

shows that the correlation between the three

measurements is positive. It means that corruption

perception is in-line with corruption reality.

Table 1: Correlation matrix of National CPI, Corruption

Cases (CC), and State Financial Loss (SFL).

CPI CC SFL

CPI 1.000 – –

CC .810** 1.000 –

SFL .628* .790** 1.000

** Significant at the 0.01 level

* Significant at the 0.05 level

4.2 The Distribution of Judicial Report

on Corruption

At the regional level, the distribution of corruption

cases and state financial loss can be seen since 2001.

Ogan Komering Ilir District was the largest in the

number of corruption cases and state financial loss at

that time. The corruption cases had increasingly

spread in various regions in 2014, Cirebon City was

the highest number of corruption cases, while the

biggest state financial loss was in Bekasi District. At

this year, the western part of Indonesia dominates

corruption practices while some are in the central

region and only a few regions in the eastern.

However, almost all regions in Indonesia have

corruption cases with various types of corruption

from 2001 to 2014; It was found that only two regions

were not indicated by corruption. There were Bungo

Tebo District in Jambi Province and Sintang District

in West Kalimantan Province (see figure 2).

This result has been strengthened by a significant

and positive correlation between the corruption cases

and the state financial loss (see table 2); nevertheless,

the island of Sumatra, Kalimantan, Bali and Nusa

Tenggara are stronger than Java and Sulawesi. In

addition, there is no significant correlation between

Maluku and Papua. It means that many corruption

cases in that area indicated do not result in state

financial loss.

Figure 2: Spatial distribution of corruption in Indonesia (A-

the number of corruption cases from 2001-2014, B-the

value of state financial loss from 2001-2014).

Table 2: Correlation matrix of Corruption Cases (CC), and

State Financial Loss (SFL).

CC SFL

CC 1.000 –

SFL .419** 1.000

** Significant at the 0.01 level

4.3 Regional Perception and Reality of

Corruption

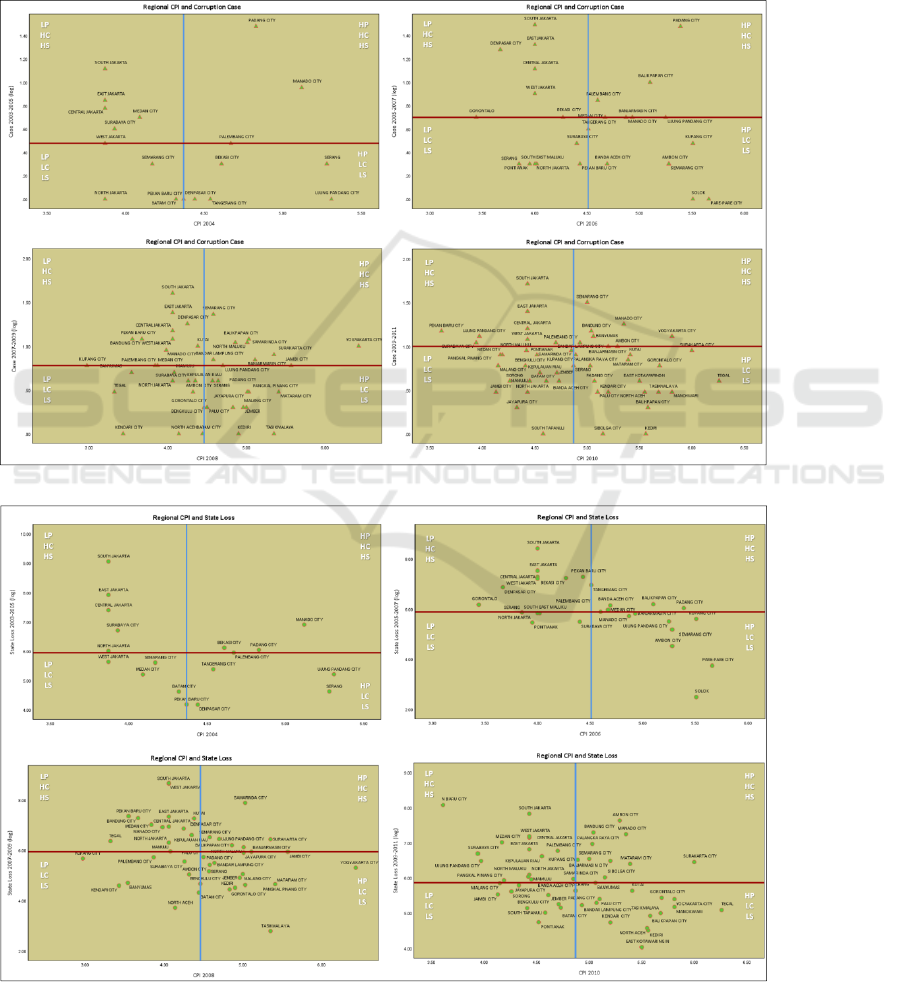

The more specific result found in the relation between

regional CPI (red circle) and two judicial report data.

In 2004, corruption perception data showed that

Kalimantan and Sulawesi Islands have a higher

perception than Sumatra, Java, and Bali Island.

Hence, it indicates that perceptually, Kalimantan, and

Sulawesi are cleaner than other areas. The same

condition had also occurred in 2006. Despite there is

an increase in corruption cases in several areas of

Kalimantan and Sulawesi, the perception has not

significantly changed (see figure 3).

Figure 3: The pattern of corruption perception and

corruption cases between 2004 and 2006.

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

224

An interesting comparison was shown in 2008 and

2010. For instance, in 2008, while there were no

corruption cases revealed in the period of 2007-2009,

the perception of corruption has a different score.

This difference may occur because the region has

different administrative types, namely District and

City. So that the perception of corruption built in the

City is far greater than in the District if there are no

corruption cases in that area. In 2010, where the

number of corruption cases increased in the period of

2009-2011, the corruption perception in

Palangkaraya City declined. Interestingly, the

perception in East Kotawaringin slightly rose.

Probably, it is because of the influence between

regions. There is a view that this area is still cleaner

than others around it, although the number of

corruption cases in the region itself increases (see

figure 4).

Figure 4: The pattern of corruption perception and

corruption cases between 2008 and 2010.

In the relation between regional perception and

state financial loss should be noted that the areas with

a large number of cases do not necessarily have a

huge amount of state losses. As shown by the

previous correlation coefficient below than 0.5.

Therefore, the value of state loss varies for each

region in a given year. For instance, in the period of

2005-2007, the number of corruption cases in

Gorontalo and Manado City is equal (5), but the value

of state financial loss in both regions is different. The

corruption that occurred in Gorontalo City resulted in

US$ 1,516,590, while in Manado City, it was US$

526,922. Interestingly, the corruption perception in

Manado City is much better than Gorontalo City in

2006. It shows that there is a negative relationship

between perception and state financial loss in both

regions (see figure 5).

Figure 5: The pattern of corruption perception and state

financial loss between 2004 and 2006.

Another interesting discussion is in the Papua

region. In the period of 2007-2009, there was no state

financial loss in Manokwari and Sorong District.

However, the corruption perception index in 2008 in

both regions was very small, although Sorong District

was still better than Manokwari District. It means that

businesspeople feel a state financial loss in that area,

but it has not been revealed by a law enforcer.

Changes occurred in the perception of corruption in

2010 for both regions. Corruption perceptions in

Manokwari District rose significantly from 3.39 to

5.81 with the value of state financial loss US$

149,242, while the perception of corruption in Sorong

declined from 4.39 to 4.26 with the value of state

financial loss US$ 416,197. From this description, it

can be said that there is a negative correlation

between perception and state financial loss in both

regions (see figure 6).

Figure 6: The pattern of corruption perception and state

financial loss between 2008 and 2010.

Perception and Reality of Corruption: A Spatiotemporal Analysis in Indonesia Sub-national Level

225

4.4 The 4-quadrant of Corruption

Measurement

From the 4-year period of regional CPI, it can be seen

several regions are in quadrant II and IV. It shows the

regions that have a small number of corruption cases,

the perception of business actors tends to improve,

and the regions that have a large amount of

corruption, the perceptions tend to deteriorate. This

result is in-line with the previous paper using

corruption perception and corruption incidence in

Russia (Belousova, Goel, and Korhonen, 2016). They

found that there is a positive relation between

perception and reality. Please take note that in their

paper, they use different perception meaning which is

0 is very clean and 10 is very corrupt. That is why the

correlation sign is positive.

Interestingly, in fact, some regions are also in

quadrant I and III. I expect that the perceptions

formed in these areas were accentuated comparing the

number of corruption cases with other regions so that

the perception is directly proportional to reality.

Over time, there are different patterns in each

region. For example, in South Jakarta, the number of

corruption cases increased in the period of 2003-

2011. In line with this, the perception of corruption is

also getting better. It describes that the more

corruption cases revealed, the perception of business

actors on corruption is getting better as well. In

Padang City, the number of corruption cases is

relatively the same in the period of 2004-2006, while

the corruption perception experienced a significant

increase in this region. However, until 2010, this

perception has decreased as the number of corruption

cases handled has declined. A much different pattern

occurred in Surabaya, the increase in the number of

corruption cases in the period 2003-2011 did not give

much chance to the corruption perception in the

period of 2004-2010 (see appendix 1).

An interesting discussion is in Manado City.

Within the four period measurements, the amount of

state financial loss rose in this city, while the

corruption perceptions also increased during this

period. It shows that there is a positive relationship

between perceptions and state financial loss overtime

in one region. Hence, people tend to have a positive

view that the state is working hard to eradicate

corruption and prosecute those implicated in it, when

the justice system is properly enforced (Bohn, 2012).

Therefore, corruption perception tends to improve in-

line with the effectiveness of law enforcement. The

same pattern also occurs in West Jakarta. The

increase in the number of state losses improves the

perception of businesspeople against corruption in

that region (see appendix 2).

5 CONCLUSION

Regional corruption measurement is essential to see

the pattern of corruption. There are three points that

can be highlighted to conclude this paper. First, there

is a negative correlation between corruption

perception and corruption reality among regions.

Second, there is a positive correlation between

corruption perception and corruption reality over

time. Third, corruption perception, corruption cases,

and state financial loss have complemented each

other in explaining the pattern of corruption in

Indonesia sub-national level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author, thanks to the Ministry of Religious

Affairs, the Republic of Indonesia, who provides the

scholarship for this research through 5000 Doktor

program.

REFERENCES

Andersson, S. and Heywood, P. M. (2009) ‘The Politics of

Perception: Use and Abuse of Transparency

International's Approach to Measuring Corruption,'

Political Studies, 57(4), pp. 746–767. doi:

10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00758.x.

Belousova, V., Goel, R. K. and Korhonen, I. (2016)

‘Corruption perceptions versus corruption incidence:

Competition for rents across Russian regions’, Journal

of Economics and Finance, 40(1), pp. 172–187. doi:

10.1007/s12197-014-9298-y.

Bhargava, V. and Bolongaita, E. (2004) Challenging

Corruption in Asia: Case Studies and a Framework for

Action. Washington, D. C: The World Bank.

Block, R. L. and Block, C. R. (1995) ‘Space, place and

crime: Hot spot areas and hot places of liquor-related

crime’, Crime and Place, 4(2), pp. 145–184.

Bohn, S. R. (2012) ‘Corruption in Latin America:

Understanding the Perception-Exposure Gap’, Journal

of Politics in Latin America, 4(3), pp. 67–95. doi:

10.1177/1866802X1200400303.

Bowers, K. J. and Johnson, S. D. (2005) ‘Domestic

Burglary Repeats and Space-Time Clusters’, European

Journal of Criminology, 2(1), pp. 67–92. doi:

10.1177/1477370805048631.

Brantingham, P. L. Brantingham, P. J. (1999) ‘A theoretical

model of crime hot spot generation’, Studies on Crime

& Crime Prevention, 8(1), pp. 7–26.

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

226

Brown, A. J. (2006) ‘What are we trying to measure?

Reviewing the basics of corruption definition’, in

Sampford, C. et al. (eds) Measuring Corruptionsuring

Corruption. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishers, pp.

57–79.

Butt, S. (2012) Corruption and law in Indonesia. New York:

Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series.

Grubesic, T. H. and Mack, E. A. (2008) ‘Spatio-Temporal

Interaction of Urban Crime’, Journal of Quantitative

Criminology, 24(3), pp. 285–306. doi: 10.1007/s10940-

008-9047-5.

Gutmann, J., Padovano, F. and Voigt, S. (2015) ‘Perception

vs. Experience: Explaining Differences in Corruption

Measures Using Microdata’, SSRN Electronic Journal.

doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2659349.

Heinrich, F. and Hodess, R. (2011) ‘Measuring

Corruption’, in Graycar, A. and Smith, R. G. (eds)

Handbook of Global Research and Practice in

Corruption. Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing,

Inc., pp. 18–33.

IMF (2017) The Role of the fund in governance issues -

Review of the guidance note - Preliminary

considerations - Background notes. Washington, D. C.

Available at:

http://www.imf.org/external/pp/ppindex.aspx.

Jacquez, G. M. (1996) ‘A k Nearest neighbour test for

spade-time interaction’, Statistics in Medicine, 15(18),

pp. 1935–1949. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-

0258(19960930)15:18<1935::AID-SIM406>3.0.CO;2-

I.

Jain, A. K. (2001) ‘Corruption: A review’, Journal of

Economic Surveys, 15(1), pp. 71–121. Available at:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-

6419.00133.

Johnston, M. (1996) ‘The search for definitions: the vitality

of politics and the issue of corruption’, International

Social Science Journal, 48(149), pp. 321–335. doi:

10.1111/1468-2451.00035.

Johnston, M. (2002) ‘Measuring the New Corruption

Rankings: Implications for Analysis and Reform’, in

Political Corruption. Routledge, pp. 865–884. doi:

10.4324/9781315126647-69.

Johnston, M. (2010) ‘Assessing Vulnerabilities to

Corruption’, Public Integrity, 12(2), pp. 125–142. doi:

10.2753/PIN1099-9922120202.

Johnston, M. and Kpundeh, S. J. (2002) ‘The measurement

problem: a focus on governance’, in Dijk, J. Van and

Ruggiero, V. (eds) Forum on Crime and Society. New

York: United Nations Publication, pp. 33–44.

Kaufmann, D. (2005) Myths and Realities of Governance

and Corruption. 8089. Munich. Available at:

http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/8089/.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A. and Mastruzzi, M. (2007)

Measuring Corruption: Myths and Realities.

Kenny, C. (2009) ‘Measuring Corruption in Infrastructure:

Evidence from Transition and Developing Countries’,

The Journal of Development Studies, 45(3), pp. 314–

332. doi: 10.1080/00220380802265066.

Kulldorff, M. and Hjalmars, U. (1999) ‘The Knox Method

and Other Tests for Space-Time Interaction’,

Biometrics, 55(2), pp. 544–552. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-

341X.1999.00544.x.

Kurer, O. (2005) ‘Corruption: An alternative approach to

definitions of corruption’, Political Studies, 53, pp.

222–239.

Loukaitou-sideris, A. (1999) ‘Hot Spots of Bus Stop

Crime’, Journal of the American Planning Association,

65(4), pp. 395–411. doi: 10.1080/01944369908976070.

Malito, D. V. (2014) Measuring Corruption Indicators and

Indices. RSCAS 2014/13.

Mauro, P. (1995) ‘Corruption and Growth’, The Quarterly

Journal of Economics, 110(3), pp. 681–712. Available

at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2946696.

Mcleod, R. H. (2000) ‘Soeharto ’ s Indonesia : A Better

Class of Corruption’, Agenda: A Journal of Policy

Analysis and Reform, 7(2), pp. 99–112.

Mikkelsen, K. S. (2013) ‘In murky waters: A disentangling

of corruption and related concepts’, Crime, Law and

Social Change, 60(4), pp. 357–374. doi:

10.1007/s10611-013-9474-6.

Miller, W. L. (2006) ‘Perceptions, experience and lies:

What measures corruption and what do corruption

measures measure?’, in Sampford, C. et al. (eds)

Measuring Corruption. Burlington, VT: Ashgate

Publishers, pp. 163–185.

Del Monte, A. and Papagni, E. (2007) ‘The determinants of

corruption in Italy: Regional panel data analysis’,

European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), pp. 379–

396. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2006.03.004.

Ng, D. (2006) ‘The impact of corruption on financial

markets’, Managerial Finance, 32(2003), pp. 822–836.

doi: 10.1108/03074350710688314.

Philp, M. (2006) ‘Corruption definition and measurement’,

in Sampford, C. et al. (eds) Measuring Corruption.

Ashgate Publishers, pp. 45–56.

Rohwer, A. (2009) Measuring Corruption: A Comparison

between the Transparency International’s Corruption

Perceptions Index and the World Bank’s Worldwide

Governance Indicators. Munich. Available at:

http://hdl.handle.net/10419/166975.

Rose, R. and Mishler, W. (2010) ‘Experience versus

perception of corruption: Russia as a test case’, Global

Crime, 11(2), pp. 145–163. doi:

10.1080/17440571003669175.

Rose, R. and Peiffer, C. (2012) Paying Bribes to Get Public

Services: A Comparative Guide to Concepts and

Measures. 494. Available at:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2

180793.

Sagovsky, A. and Johnson, S. D. (2007) ‘When Does

Repeat Burglary Victimisation Occur?’, Australian &

New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 40(1), pp. 1–26.

doi: 10.1375/acri.40.1.1.

Svensson, J. (2005) ‘Eight Questions about Corruption’,

Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(3), pp. 19–42.

Theobald, R. (1990) Corruption, Development and

Underdevelopment. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Treisman, D. (2007) ‘What Have We Learned About the

Causes of Corruption from Ten Years of Cross-

National Empirical Research?’, Annual Review of

Perception and Reality of Corruption: A Spatiotemporal Analysis in Indonesia Sub-national Level

227

Political Science, 10(1), pp. 211–244. doi:

10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.081205.095418.

United Nations (2004) United Nations convention against

corruption. New York, USA.

Wedeman, A. (2004) ‘The Intensification of Corruption in

China’, 35(116), pp. 85–103.

APPENDIX

1. Reginal CPI and corruption cases

2. Regional CPI and state financial loss

ICOACI 2019 - International Conference on Anti-Corruption and Integrity

228