The Association between Forgiveness and Life Satisfaction

Dewa Fajar Bintamur

Universita Indonesia

Keywords: Forgiveness, Life Satisfaction, Indonesian, Young Adulthood

Abstract: This study's objective is to investigate whether there is a relationship between dispositional forgiveness and

life satisfaction at working young adulthood in Indonesia. According to Thompson et al. (2005), there are

three forms or dimensions of dispositional forgiveness: Self-forgiveness, Other-forgiveness, and Situation-

forgiveness. While life satisfaction is the cognitive process of an individual's subjective evaluation of one's

entire life, and it is an indicator of one's well-being. Previous studies have shown that both forgiveness and

life satisfaction associated with social and cultural factors. The instruments to measure forgiveness and life

satisfaction were Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS) and SWLS (Satisfaction with Life Scale). Convenient

sampling was the sampling technique to collect data from 167 participants. They were males and females

who in the young adulthood stage, and live in Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi (Jabodetabek

region). The result shows a significant positive correlation between forgiveness and life satisfaction. Where

Self-forgiveness and Situation-forgiveness highly significant with life satisfaction, while Other-forgiveness

moderately significant with life satisfaction.

1 INTRODUCTION

The fast advancement of technology-led human to

another industrial revolution, industrial revolution

4.0, where the convergence of cyberspace with the

physical world could happen, where mass

production systems would no longer produce

uniform products, but it could produce customized

products. Industrial revolution 4.0 is more than just a

change in production and distribution systems. It

also would significantly change the process of

formation, exchange, and distribution of economic,

political, and social values (Philbeck & Davis,

2018). In other words, the world is in a disruptive

era, an era that would change the societies' and

humans' lifestyle. Efforts to survive and adapt to the

changes that occur could cause conflicts between the

parties who had previously cooperated. An ironical

condition because the goal of technological

advancements is to make human life more

comfortable and happier.

The Japanese cabinet in 2016 proposed "Society

5.0" or a "Super Smart Society." Technological

advancements, in that proposal, were utilized as

much as possible for human security and welfare.

Humans become the central actors in the

development of technology and science. Technology

means to meet the needs of human life sustainably

regardless of age, sex, region, and language

(Shiroishi, Uchiyama & Suzuki, 2018).

A joint effort or a process carried out by various

parties will be needed to create Society 5.0.

Unfortunately, there would be the possibility of

conflict among people in it. Conflicts can bother the

achievement of group or individual goals. Mistakes

made by oneself, others, and the situation could

cause failure to achieve goals. Therefore, the ability

to forgive self, others, and situations where needed.

The ability to forgive allows one to keep trying to

achieve his goals. Goals achievements will provide a

sense of satisfaction in life. This study wants to

examine the relationship between forgiveness and

life satisfaction at working young adults since they

are most affected by this disruptive era.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Forgiveness is a process that has a motivational and

emotional component (Sandage & Williamson,

2007; Cheng & Yim, 2008; Swickert, Robertson, &

Baird, 2016). The main features of the forgiveness

process are the reduction of vengeful and angry

thoughts, feelings, and motives, which can be

174

Bintamur, D.

The Association between Forgiveness and Life Satisfaction.

DOI: 10.5220/0009440601740180

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Psychology (ICPsy 2019), pages 174-180

ISBN: 978-989-758-448-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

accompanied by an increase in positive thoughts,

feelings, and motives (Wade, et. Al., 2014 in Cerci

& Colucci, 2018). The definition of forgiveness in

this study is from Thompson et al. (2005) that

defined forgiveness as “... the framing of a perceived

transgression such that one's responses to the

transgressors, transgression, and sequelae of the

transgression are transformed from negative to

neutral or positive. The source of a transgression,

and therefore the object of forgiveness, maybe

oneself, another person or person, or a situation that

views one being beyond anyone's control (e.g., an

illness, '' fate, '' or a natural disaster) "

Forgiveness allows one to overcome

interpersonal offense through a prosocial process

that would have a positive impact on victims and

perpetrators, not through denial, justification, or

revenge (Fehr, Gelfand, & Nag, 2010). Forgiveness

allows one to eliminate hurt feelings and hatred

when responding to the transgression (Swickert,

Robertson, & Baird, 2016). Forgiveness has a

positive impact on survivors. Because of the process

of forgiveness, factors such as cognition,

physiological responses, behavioral intentions,

emotions, motivation, and possibly behavior toward

the offender become more positive over time

(Fernández-Capo et al., 2017).

There are two levels to measure forgiveness in

research, dispositional level or offense-specific level

(McCullough, Pargament, & Thoresen, 2000 in

Cerci & Colucci, 2018). Dispositional forgiveness or

trait forgiveness is the forgiving nature of someone

that stable in various situations and times. Offense-

specific forgiveness is forgiveness that has been

done by someone for a specific event in his or her

life (Cerci & Colucci, 2018). In this study, the

forgiveness level measured was dispositional or trait

forgiveness. There are three forms of dispositional

forgiveness according to Thompson et al. (2005):

Self-forgiveness or ability to forgive oneself; Other-

forgiveness or ability to forgive another person or

persons; Situation-forgiveness or ability to forgive a

situation which is beyond anyone's control, such as

an illness or natural disaster.

Forgiveness is related to age, gender, beliefs,

social-cultural, and religious practice. Older adults

are more willing to forgive than people who are in

the stage of middle-aged and young adults (Mullet et

al., 1998; Cheng & Yim, 2008). Allemand's study

(2008) showed that there was a difference between

forgiveness that has been done by older people

compared to forgiveness that has been done by

younger people. Older people would forgive their

acquaintances and their friends as well. On the other

hand, younger people would prefer to forgive their

friends than their acquaintances.

There were also small to moderate yet significant

differences between gender and forgiveness,

according to a study by Miller, Worthington Jr. &

McDaniel (2008). Swickert, Robertson, & Baird

(2016) found that women were more forgiving than

men. Younger women were more likely to

empathize with transgressors compared to younger

men. However, Swickert, Robertson, & Baird (2016)

stated that there was still a lack of clarity in the

existing literature on the relationship between

gender and forgiveness.

Social-cultural factors also related to forgiveness

(Ho & Fung, 2011; Sandage & Williamson, 2007).

Forgiveness is an interpersonal construct since it is a

process that involves changes in cognition, emotion,

motivation, and behavior of someone against the

transgressor (Ho & Fung, 2011). People who live in

individualistic cultures have a different focus than

people who live in collectivistic cultures. Those who

live in individualistic cultures focus more on

distinguishing themselves from others and striving

to achieve personal goals, while people who live in

collectivistic cultures emphasize more on the norms

of togetherness and relationships with others to be

able to live in harmony with others (Ho &

Worthington, 2018).

People who have a lower level of forgiveness

would have lower levels of distress tolerance and

tend to be more hostile (Matheny et al., (2017).

Longitudinal research conducted by Toussaint, et al.

(2018) concluded that there is a more significant

association of hostility with cognitive impairment

that occurs more than ten years, and the effects

associated with hostility on this cognition lessened

with being more forgiving. Lack of forgiveness is

also associated with hyper-competitiveness, while

personal development competitiveness is positively

associated with forgiveness (Collier et al., 2010).

The level of forgiveness is also related to scores

related to PTSD symptoms. However, it also needs

to consider other variables such as demographics,

the relationship between transgressors and survivors

of trauma, type, and severity of the trauma, and

other relevant variables (Cerci & Colucci, 2018).

Research conducted by Bryan, Theriault, and Bryan

(2015) on military and veteran personnel indicated

that self-forgiveness significantly distinguishes

participants who attempt suicide and those who only

think of committing suicide. Besides being mentally

healthier, forgiveness is also related to one's physical

health and the longevity of Toussaint, Owen, &

Cheadle (2012).

The Association between Forgiveness and Life Satisfaction

175

A forgiving person would have a low level of

distress and a lower level of distress associated with

a higher level of happiness (Toussaint et. Al., 2016).

In other words, there is a positive correlation

between forgiveness and well-being (Toussaint &

Friedman, 2009; Toussaint et al., 2016). One of the

constructs of well-being is subjective well-being

from Diener (1984), and life satisfaction is a

component of subjective well being. Life satisfaction

is the cognitive process of an individual's subjective

evaluation of his entire life (Diener, Suh, Lucas &

Smith, 1999). The evaluation is based on a

comparison of the life experienced by a person with

subjective standards (Diener et al., 1985).

According to Diener, Lucas, Schimmack, and

Helliwell (2009), life satisfaction is an indicator of

individual well-being and social well-being.

Individuals who have a high level of life satisfaction

are those who are successful in developing

relationships with others, at work, and in their

physical functions. They also have made more

money and have been better at dealing with the

diseases they experience (Lewis, 2010 in Dogan &

Celik, 2014).

Life satisfaction also has related to age. Buetel et

al. (2009) found that there was a relationship

between age and life satisfaction on female

respondents from adolescent to late adulthood stage.

Another research conducted by Beutel et al. (2010)

on male respondents at the same developmental

stage (adolescence to late adulthood) showed no

significant difference in life satisfaction that related

to age. While Baird, Lucas, & Donnellan's (2010)

research finding concluded that life satisfaction does

not decrease too much throughout adulthood.

However, there is a sharp decline in respondents

aged over 70 years (Baird, Lucas, & Donnellan,

2010). A study conducted by Jovanović (2017)

showed that there was different life satisfaction

between adolescents and adults. Adolescents' life

satisfaction was higher than in adults' life

satisfaction. Siedlecki, Tucker-Drob, Oishi, &

Salthouse (2008) research also obtained similar

results. They also found that the level of education

was related to the satisfaction of one's life.

Several studies have found that there are

differences in the level of life satisfaction between

men and women. Women reported higher levels of

life satisfaction than women (Jovanović, 2017).

Research conducted by Beutel, et al., (2009)

revealed that factors related to life satisfaction in

general in women are the level of resilience, good

household income, the presence of partners, the

absence of anxiety and depression, not unemployed,

positive self-esteem, religious affiliation, and age.

General life satisfaction in men is related to the level

of resilience, previous unemployment conditions, the

presence of partners, high self-esteem, household

income, the absence of generalized anxiety disorder,

and depression (Beutel et al., 2010).

Cultural factors also affect one’s life satisfaction.

Previous studies have shown differences in life

satisfaction levels in different countries.

Communities in Pacific Rim countries do not have a

strong tendency to evaluate abstract things

positively, while people in Latin American countries

have a strong tendency to value global domains

positively (Diener et al. 2000). Diener, Inglehart,

and Tay (2013) said that life satisfaction level based

on earned income in Latin American society is

higher than in Asian societies, which have a

Confucian culture. The ability of individuals to meet

the cultural demands that exist in a collectivistic

society affects the satisfaction of life, while this does

not apply to ones that live in an individualistic

society. Since in an individualistic society,

independence, uniqueness, and autonomy are

considered culturally relevant (Li & Hamamura,

2010).

This study investigated whether there was a

significant relationship between forgiveness and life

satisfaction at working young people who live in

Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi

(Jabodetabek region). Although previous researches

indicate that there has been a significant relationship

between forgiveness and well-being, this study still

needed to be done because both forgiveness and life-

satisfaction variables have associated with

demographic variables such as age, gender, social,

and cultural.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

The respondents of this study were working young

adults who live in the Greater Jakarta area (Jakarta,

Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi) or

Jabodetabek region. The sampling technique to

obtained cross-sectional data in this non-

experimental study was convenience sampling.

There were a total of 167 people who participated in

this study, 118 females and 49 males. Each

participant was asked to fill a self-report instrument

(questionnaire) which distributed online.

The Bahasa Indonesia version of the Heartland

Forgiveness Scale (HFS), which originally

developed by Thompson et al. (2005), used to

measure dispositional forgiveness. There were three

ICPsy 2019 - International Conference on Psychology

176

dimensions in HFS: self-forgiveness, other-

forgiveness, and situation-forgiveness. Each

dimension consisted of 6 items, and each item

consisted of six Likert-like scales; scale: 1 =

Strongly disagree to 6 = Strongly agree. The

minimum score was 18, and the maximum score was

108. The reliability value of HFS on the self-

forgiveness dimension α = 0.673, the other-

forgiveness dimension α = 0.773, and the situation-

forgiveness dimension α = 0712. HFS reliability

scores for measuring forgiveness constructs are α =

0.814 and ω = 0.822.

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) was a

unidimensional measurement tool which initially

developed by Diener et al. (1985) to measure life

satisfaction. This research used the Bahasa Indonesia

version of SWLS, which consists of 5 (five) items

with 6 Likert scale likes; scale 1 = Strongly disagree

to 6 = Strongly agree. Thus, the minimum score for

the variable life satisfaction was 5, and the

maximum score was 30. There were no unfavorable

(reversed) items in this measuring instrument. The

SWLS reliability value of the sample data in this

study is α = 0.788.

Demographic data and distribution scores of the

research variables were analyzed using descriptive

statistics. The statistical technique for testing the

hypothesis of this research is the correlational

technique. This study used Jamovi statistical

software version 1.0.0 (Jamovi, 2019) to analyze

research data.

4 RESULT

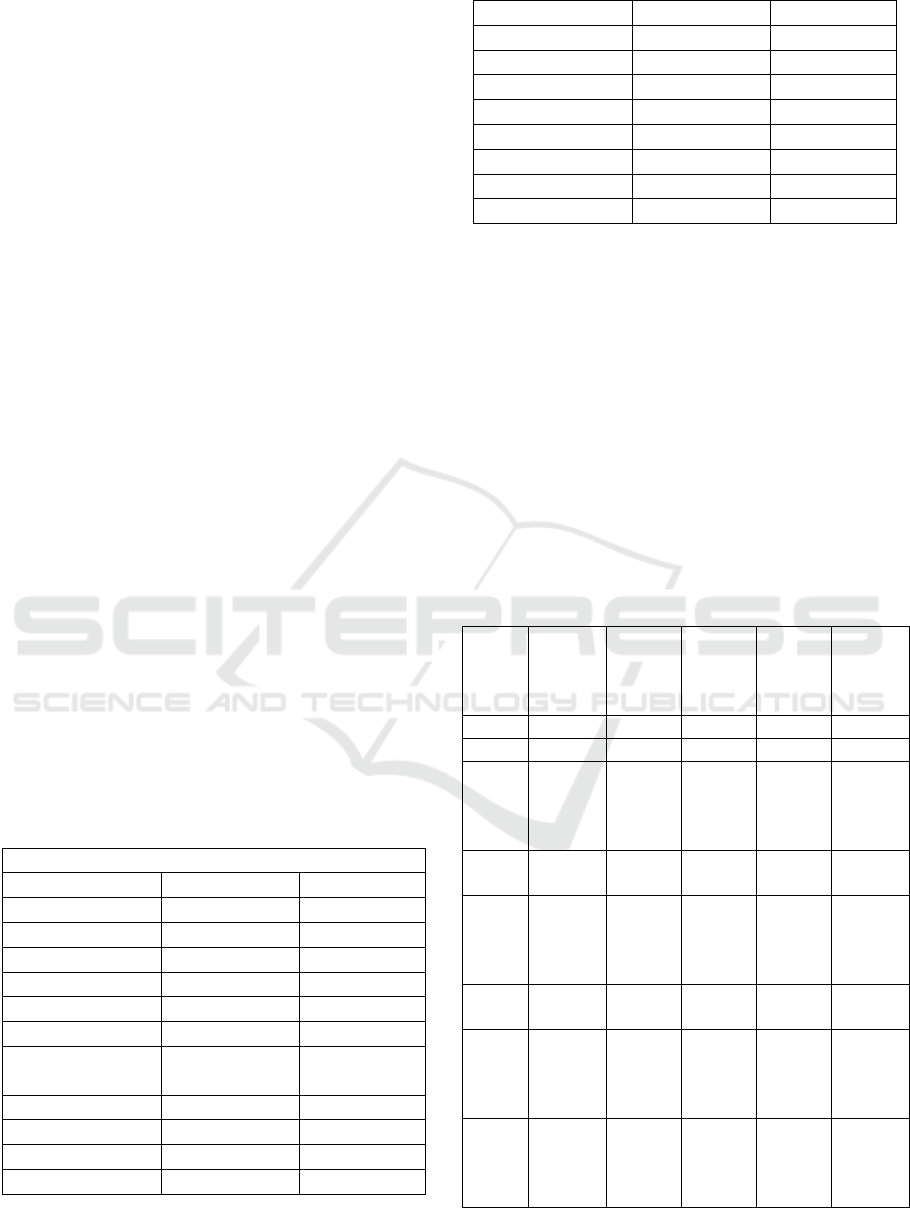

Table 1: Demographic Data.

Demographic Data

Mean Std Dev

Age 28.6 4.50

Frequency Percentage

Sex

Male 49 29.3

Female 118 70.7

Education

Senior High

School

3 1.8

Diploma/Academy 7 4.2

Undergraduate 115 68.9

Graduate 42 25.1

Marital Status

Not Married 107 64.1

Married 60 35.9

Religion

Islam 107 64.1

Christian 22 13.2

Catholic 32 19.2

Hindu 1 0.6

Buddha 2 1.2

Others 3 1.8

Demographic data on respondents' age reveals

that most of the respondents are younger than 33

years old of age (M = 28.5, SD = 4.48). Most of the

respondent’s gender are women (70.7%), and less

than a third of them are men (29.3%). The education

level of the respondents is mostly Bachelor (68.9%),

followed by Masters (25.1%), Diploma/Academy

(4.2%), and Senior High School level (1.8%). The

proportion of unmarried respondents are nearly

doubled (64.1%) than the proportion of married

respondents (35.9%). Most respondents’ religions

are Muslim (64.1%), then Catholic (19.2%),

Protestant (13.2%) and Buddhists, Hindus, and

Others (3.6%).

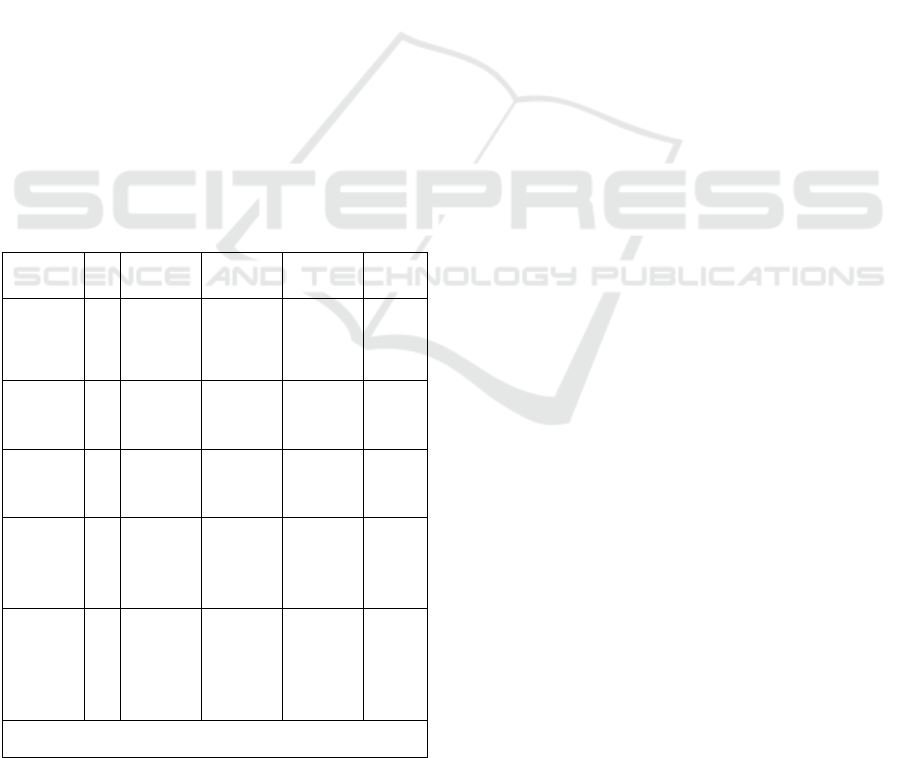

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics.

Forgiv

eness

Self-

forgiv

eness

Other-

forgiv

eness

Situati

on-

forgiv

eness

Life-

Satisfa

ction

N 167 167 167 167 167

Mean 4.05 3.86 4.10 4.17 4.04

Stand

ard

deviat

ion

0.559 0.742 0.782 0.687 0.808

Skew

ness

-0.351 -0.134 -0.580 -0.110 -0.367

Std.

error

skew

ness

0.188 0.188 0.188 0.188 0.188

Kurto

sis

0.573 0.215 0.341 0.416 -0.393

Std.

error

kurto

sis

0.374 0.374 0.374 0.374 0.374

Shapi

ro-

Wilk

p

0.281 0.447 0.002 0.195 0.004

The Association between Forgiveness and Life Satisfaction

177

The mean score of self-forgiveness (Mean =

3.86, SD = 0.742) is lower than other-forgiveness

(M = 4.10, SD = 0.782) and situation-forgiveness

(M = 4.17, SD = 0.687). One of the possible

explanations for that condition is because the

reliability of the self-forgiveness dimension was

modest (α = 0.673). Another explanation is because

it is harder to determine self-forgiveness since there

was no feedback from other people that one’s could

use as a reference. However, unlike self-forgiveness,

for the two other dimensions, which are other-

forgiveness and situation-forgiveness, respondents

can get feedback or comparison that can be used to

determine the level of forgiveness. Therefore, it

needs further researches on self-forgiveness in

collectivistic culture societies.

The distribution scores of other-forgiveness (M =

4.10, SD = 0.782) and life satisfaction (M = 4.04,

SD = 0.808) are not normal (Shapiro-Wilk < 0.01).

Whereas the distribution of the other scores is

considered normal. The alternative statistical

technique to calculate the correlations among those

variables was Spearman's Rho correlation.

Spearman's Rho is a correlation technique which

categorized as a non-parametric statistic.

Consequently, the result of this study could not be

generalized to the population.

Table 3: Correlations

Varia-

bles

1 2 3 4 5

1. Life

Satisfac

tion

- 0.382

***

0.299

***

0.178

*

0.326

***

2.

Forgive

ness

- 0.730

***

0.711

***

0.810

***

3. Self-

forgive

ness

- 0.224

**

0.488

***

4.

Other-

forgive

ness

-

0.401

***

5.

Situatio

n-

forgive

ness

-

Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Forgiveness and life-satisfaction have a

significant positive correlation (165) = 0.382, p>

0.001, r

2

= 0.146. This means, the higher one's level

of forgiveness, his or her level of life-satisfaction is

also higher. All dimensions of forgiveness have

significant positive correlation with life-satisfaction.

The dimension of forgiveness which has the highest

correlation with life-satisfaction is Situation-

forgiveness (165) = 0.326, p> 0.001, r

2

= 0.106,

then the correlation level between the dimensions of

Self-forgiveness and life-satisfaction (165) =

0.299, p> 0.001, r

2

= 0.089, while the dimension

with the lowest level of correlation with life-

satisfaction is the Other-forgiveness dimension

(165) = 0.178, p = 0.011, r

2

= 0.032.

5 DISCUSSION

The result of this study shows that there is a

significant positive relationship between life-

satisfaction and dispositional forgiveness. All its

dimensions, namely self-forgiveness, other-

forgiveness, and situational-forgiveness, also have

significant positive correlations with life-

satisfaction. These results are similar to the results

of studies that were conducted by Toussaint &

Friedman (2009), who also used self-report methods

(HFS & SWLS questionnaires), and cross-sectional

design. The coefficient correlations in their study

were slightly higher than the coefficient correlations

in this study. It might due to their participants were

relatively homogeneous respondents (outpatient

psychotherapy).

The measurement of forgiveness in this study is

general forgiveness or dispositional level

forgiveness (Thompson et al., 2005), not case-

specific forgiveness. Therefore, a study on the

relationship between case-specific forgiveness and

life satisfaction needs to do. Because in specific

cases, several things could affect one's forgiveness,

such as the relationship between transgressors and

survivors of trauma, type, and severity of the trauma

(Cerci & Colucci, 2018). The results of that study

would figure out the consistency of the association

between forgiveness and life satisfaction.

Forgiveness construct in this study has a similar

meaning with forgivingness construct (Suwartono,

Prawasti, & Mullet, 2007); both of those constructs

refer to dispositional forgiveness. Several studies

have revealed that dispositional forgiveness

associated with culture. A study about forgivingness

conducted by Suwartono, Prawasti, & Mullet (2007)

has shown the influence of individualistic culture

and collectivistic culture on forgiveness. However,

research conducted by Paz, Neto, & Mullet (2008)

ICPsy 2019 - International Conference on Psychology

178

shows that there were no differences caused by

cultural factors. According to Paz et all (2008), there

may be other factors in the culture that can influence

forgiveness; one of them is religion. That opinion

referred to Paz, R., Neto, F., & Mullet, E. (2007)

study result, which showed that there was different

forgivingness in Buddhists and Christians who live

in China.

Other than those things above, since this study

only controlled the developmental stage (young

adulthood) or respondents. Consequently, it cannot

provide a picture or comparison of forgiveness and

life satisfaction with other developmental stages.

Other demographic factors, such as gender,

occupation, income, and ethnicity, were not

controlled, and since the distribution of respondents

in those demographic factors equivalently

distributed, then statistical calculations to make the

comparison.

Another limitation of this study is convenient

sampling (non-random sampling), self-administered

data collection, and cross-sectional design. The

convenience sampling method only could reach

people that can be met or contacted and who have

had the willingness to participate in data collection.

Usually, in this method, people in negative affect

would not want to participate in data collection. A

self-administered method is also vulnerable to

faking-good or faking-bad responses, and the cross-

sectional method could only measure forgiveness

and life-satisfaction at a time.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, Forgiveness had a highly significant

positive correlation with life satisfaction. Where

Self-forgiveness and Situation-forgiveness were

highly significant with life satisfaction, while Other-

forgiveness was moderately significant with life

satisfaction.

These study results imply that further research

about factors that relate to forgiveness in Indonesia

will be needed since Indonesia is a plural country. A

country which consists of multi-cultures and multi-

religions country. Both forgiveness and life-

satisfaction constructs are related to the culture

where someone lives and religion that one's belief.

REFERENCES

Allemand, M. (2008). Age differences in forgivingness:

The role of future time perspective. Journal of

Research in Personality, 42(5), 1137-1147.

Arrindell, W. A., Meeuwesen, L., & Huyse, F. J. (1991).

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS):

Psychometric properties in a non-psychiatric medical

outpatients sample. Personality and individual

differences, 12(2), 117-123.

Baird, B. M., Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2010).

Life satisfaction across the lifespan: Findings from

two nationally representative panel studies. Social

indicators research, 99(2), 183-203.

Beutel, M. E., Glaesmer, H., Decker, O., Fischbeck, S., &

Brähler, E. (2009). Life satisfaction, distress, and

resiliency across the life span of women. Menopause,

16(6), 1132-1138.

Beutel, M. E., Glaesmer, H., Wiltink, J., Marian, H., &

Brähler, E. (2010). Life satisfaction, anxiety,

depression, and resilience across the life span of men.

The Aging Male, 13(1), 32-39.

Bryan, A. O., Theriault, J. L., & Bryan, C. J. (2015). Self-

forgiveness, posttraumatic stress, and suicide attempts

among military personnel and veterans. Traumatology,

21(1), 40.

Cerci, D., & Colucci, E. (2018). Forgiveness in PTSD

after man-made traumatic events: A systematic

review. Traumatology, 24(1), 47.

Cheng, S. T., & Yim, Y. K. (2008). Age differences in

forgiveness: The role of future time perspective.

Psychology and Aging, 23(3), 676.

Collier, S. A., Ryckman, R. M., Thornton, B., & Gold, J.

A. (2010). Competitive personality attitudes and

forgiveness of others. The Journal of Psychology,

144(6), 535-543.

Cotton Bronk, K., Hill, P. L., Lapsley, D. K., Talib, T. L.,

& Finch, H. (2009). Purpose, hope, and life

satisfaction in three age groups. The Journal of

Positive Psychology, 4(6), 500-510.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and

validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators

Research, 112(3), 497-527.

Diener, E., Napa-Scollon, C. K., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., &

Suh, E. M. (2000). Positivity and the construction of

life satisfaction judgments: Global happiness is not the

sum of its parts. Journal of happiness studies, 1(2),

159-176.

Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., Autin, K. L., & Bott, E. M.

(2013). Calling and life satisfaction: It's not about

having it, it's about living it. Journal of Counseling

Psychology, 60(1), 42.

Fehr, R., Gelfand, M. J., & Nag, M. (2010). The road to

forgiveness: a meta-analytic synthesis of its situational

and dispositional correlates. Psychological Bulletin,

136(5), 894.

Fernández-Capo, M., Fernández, S. R., Sanfeliu, M. G.,

Benito, J. G., & Worthington Jr, E. L. (2017).

Measuring forgiveness. European Psychologist.

The Association between Forgiveness and Life Satisfaction

179

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Melin, R., & Fugl-Meyer, K. S.

(2002). Life satisfaction in 18-to 64-year-old Swedes:

in relation to gender, age, partner, and immigrant

status. Journal of rehabilitation medicine, 34(5), 239-

246.

Ho, M. Y., & Fung, H. H. (2011). A dynamic process

model of forgiveness: A cross-cultural perspective.

Review of General Psychology, 15(1), 77-84.

Ho, M. Y., & Worthington, E. L. (2018). Is the concept of

forgiveness universal? A cross-cultural perspective

comparing western and eastern cultures. Current

Psychology, 1-8.

Li, L. M. W., & Hamamura, T. (2010). Cultural fit and life

satisfaction: Endorsement of cultural values predicts

life satisfaction only in collectivistic societies. Journal

of Psychology in Chinese Societies, 11(2), 109.

Matheny, N. L., Smith, H. L., Summers, B. J., McDermott,

K. A., Macatee, R. J., & Cougle, J. R. (2017). The role

of distress tolerance in multiple facets of hostility and

willingness to forgive. Cognitive therapy and

research, 41(2), 170-177.

Miller, A. J., Worthington Jr, E. L., & McDaniel, M. A.

(2008). Gender and forgiveness: A meta-analytic

review and research agenda. Journal of Social and

Clinical Psychology, 27(8), 843-876.

Mullet, E., Houdbine, A., Laumonier, S., & Girard, M.

(1998). “Forgivingness”: Factor structure in a sample

of young, middle-aged, and elderly adults. European

Psychologist, 3(4), 289-297.

Pavot, W., Diener, E. D., Colvin, C. R., & Sandvik, E.

(1991). Further validation of the Satisfaction with Life

Scale: Evidence for the cross-method convergence of

well-being measures. Journal of personality

assessment, 57(1), 149-161.

Paz, R., Neto, F., & Mullet, E. (2007). Forgivingness:

Similarities and differences between Buddhists and

Christians living in China. The international journal

for the psychology of religion, 17(4), 289-301.

Paz, R., Neto, F., & Mullet, E. (2008). Forgiveness: A

China-Western Europe comparison. The Journal of

Psychology, 142(2), 147-158.

Philbeck, T., & Davis, N. (2018). The Fourth Industrial

Revolution: Shaping a New Era. Journal of

International Affairs, 72(1), 17.

R Core Team (2018). R: A Language and environment for

statistical computing. [Computer software]. Retrieved

from https://cran.r-project.org/.

Revelle, W. (2019). Psych: Procedures for Psychological,

Psychometric, and Personality Research. [R package].

Retrieved from https://cran.r-

project.org/package=psych.

Sandage, S. J., & Williamson, I. (2007). Forgiveness in

cultural context. In Handbook of forgiveness (pp. 65-

80). Routledge.

Shiroishi, Y., Uchiyama, K., & Suzuki, N. (2018). Society

5.0: For human security and well-being. Computer

,

51(7), 91-95.

Siedlecki, K. L., Tucker-Drob, E. M., Oishi, S., &

Salthouse, T. A. (2008). Life satisfaction across

adulthood: Different determinants at different ages?.

The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(3), 153-164.

Suwartono, C., Prawasti, C. Y., & Mullet, E. (2007).

Effect of culture on forgivingness: A Southern Asia–

Western Europe comparison. Personality and

Individual Differences, 42(3), 513-523.

Swickert, R., Robertson, S., & Baird, D. (2016). Age

moderates the mediational role of empathy in the

association between gender and forgiveness. Current

Psychology, 35(3), 354-360.

The jamovi project (2019). jamovi. (Version 1.0.0)

[Computer Software]. Retrieved from

https://www.jamovi.org.

Thompson, L. Y., Snyder, C. R., Hoffman, L., Michael, S.

T., Rasmussen, H. N., Billings, L. S., ... & Roberts, D.

E. (2005). Dispositional forgiveness of self, others,

and situations. Journal of personality, 73(2), 313-360.

Toussaint, L. L., Owen, A. D., & Cheadle, A. (2012).

Forgive to live: Forgiveness, health, and longevity.

Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 35(4), 375-386.

Toussaint, L. L., Shields, G. S., Green, E., Kennedy, K.,

Travers, S., & Slavich, G. M. (2018). Hostility,

forgiveness, and cognitive impairment over 10 years

in a national sample of American adults. Health

Psychology, 37(12), 1102.

Toussaint, L., & Friedman, P. (2009). Forgiveness,

gratitude, and well-being: The mediating role of affect

and beliefs. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(6), 635.

Toussaint, L., Shields, G. S., Dorn, G., & Slavich, G. M.

(2016). Effects of lifetime stress exposure on mental

and physical health in young adulthood: How stress

degrades and forgiveness protects health. Journal of

health psychology, 21(6), 1004-1014.

ICPsy 2019 - International Conference on Psychology

180