Socio-demographic Factors and Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC)

Practice among Mothers Who Had Low Birth Weight’s Babies in

Cilincing Village, Jakarta

Intan Silviana Mustikawati

Department of Public Health, Universitas Esa Unggul, Jl. Arjuna Utara No. 6A, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Kangaroo Mother Care, Practice, Socio-demographic, Low Birth Weight’s Babies.

Abstract: Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) is early, continuous, and prolonged skin–to– skin contact between mother

and newborn babies. Many factors affecting KMC practice among mothers at home. The purpose of this

study was to assess the relationship between socio-demographic factors and KMC practice among mothers

who had Low Birth Weights (LBW)’s babies. This was a cross-sectional study conducted in Cilincing

village, North Jakarta. A sample of 30 mothers who had LBW’s babies post-discharged from Koja Hospital,

North Jakarta was selected for this study by consecutive sampling. The data were collected by

questionnaires, interviews, and observation, and analyzed by Mann-Whitney U-test. The mean age of

respondents was 31 years old, mean parity was 2 children, the majority of them were low education (64%),

not working (100%), and distance to health services was less than 1 km (56%). The majority of respondents

had bad KMC practice (76%). It was found that age had a statistically significant relationship with KMC

practice among mothers who had LBW’s babies (z=-2,263, p value<0,05, CI 95%). Bad KMC practice was

due to younger mothers. The need for support from family, health workers, and community to increase

KMC practice among LBW’s babies’ mothers at home.

1 INTRODUCTION

Neonatal mortality is a major challenge in reducing

child mortality rates in many developing countries.

Data from the Indonesian Demographic and Health

Surveys (National Population and Family Planning

Board, 2013) show a slower rate of decline of

Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR) than Infant

Mortality Rate (IMR) and Under-five Mortality Rate

(UMR). The majority of child mortality was

occurred during the neonatal period, largely due to

low birth weight (LBW) and prematurity (28%) and

severe infections (26%) (Lawn et al., 2015). LBW

infants will be at risk for infectious diseases, delays

in growth and development, and death during

childhood (Soleimani et al., 2014; Ballot et al.,

2012).

One of the efforts to care for LBW infants is

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC). The main purpose

of KMC is to take care of the infants' temperature by

skin-to-skin (STS) contact between mother and

infant (WHO, 2003). Some studies show that KMC

is beneficial for improving breastfeeding, increase

the bond between mother and infants, weight gain,

increase body length and head circumference,

decrease hospital stay, and increase survival rate

(Sloan et al., 1994; Charpak & Ruiz-pela, 2000;

Charpak et al., 2017).

The practice of KMC usually starts at the

hospital and continues at home after LBW’s babies

discharge from the hospital (with supervision by the

local health officer). But the difference between

hospital and home conditions makes KMC practice

less optimal to be implemented at home. In

hospitals, mothers get adequate facilities and good

supervision from health workers, so that they can

practice KMC optimally. At home, there are many

obstacles in the implementation of KMC such as

housework, taking care of other children, and family

support (Maras et al., 2010; Quasem et al., 2003;

Nguah et al., 2011). The success of KMC practice at

home is influenced by local conditions in the home

and community.

Studies on KMC perceptions and practices in

hospitals in Jakarta have been conducted, one of

which was carried out in Koja Hospital, North

220

Mustikawati, I.

Socio-demographic Factors and Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) Practice among Mothers Who Had Low Birth Weight’s Babies in Cilincing Village, Jakarta.

DOI: 10.5220/0009589302200223

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Health (ICOH 2019), pages 220-223

ISBN: 978-989-758-454-1

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Jakarta (Bergh et al., 2018). The study assessed

perceptions and practices of KMC among LBW’s

babies’ mothers who were hospitalized and produce

a referral system between hospital and primary

healthcare to pick up and deliver LBW’s babies’

mothers to their home. However, the perceptions and

practices of KMC among LBW’s babies’ mothers

after discharged from Koja Hospital, North Jakarta

are not yet known. There are many factors will

affect KMC practice among LBW’s babies’ mothers

at home, such as mothers, infants, family, health

workers, and community factors. The aim of this

study was to assess the relationship between socio-

demographic factors and KMC practice among

LBW’s babies’ mothers in Cilincing village, Jakarta.

2 METHOD

This study was a cross-sectional design, conducted

in Cilincing village, North Jakarta. A sample of 30

mothers who had LBW’s babies post-discharged

from Koja Hospital, North Jakarta was selected for

this study by consecutive sampling. The dependent

variable was KMC practice and independent

variables were maternal age, education, parity,

working status, and distance to health services.

The data were collected by questionnaire,

interview, and observation. A questionnaire was used

to identify socio-demographic factors and interview

and observation was used to explore KMC practice.

The data were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U-test.

3 RESULTS

The study was to assess the relationship between

socio-demographic factors and KMC practice among

mothers who had LBW’s babies.

3.1 Socio-Demographic Factors of

LBW’s Babies’ Mothers

The mean age of respondents was 31 years old, mean

parity was 2 children, the majority of them were low

education (64%), not working (100%), and distance to

health services was less than 1 km (56%).

3.2 Practice of KMC among LBW’s

Babies’ Mothers

All of LBW’s babies’ mothers in this study were

continue to practice KMC at home with a mean

duration of KMC practice is 3 hours a day. But none

of LBW’s babies’ mothers who practiced KMC

continuously for 24 hours a day. The majority of the

mothers were practiced KMC in the morning and

night.

Based on the observation, the majority of LBW’s

babies’ mothers in this study was practiced KMC

inadequately. They were not practiced KMC with

the correct position. The majority of LBW’s babies’

mothers were practiced KMC with the position

neither the baby's head was not turned left or right

with the position of a slight look, nor the hands and

feet of the baby in a bent position like a frog. Some

of them are not confident in practicing KMC and let

their family practice KMC.

3.3 Relationship between

Socio-Demographic Factors and

KMC Practice

Younger mothers (Mean=29,26, SD=7,17) were

likely to practice bad KMC than older mothers

(Mean=36,50 SD=4,04). It showed in the table

below.

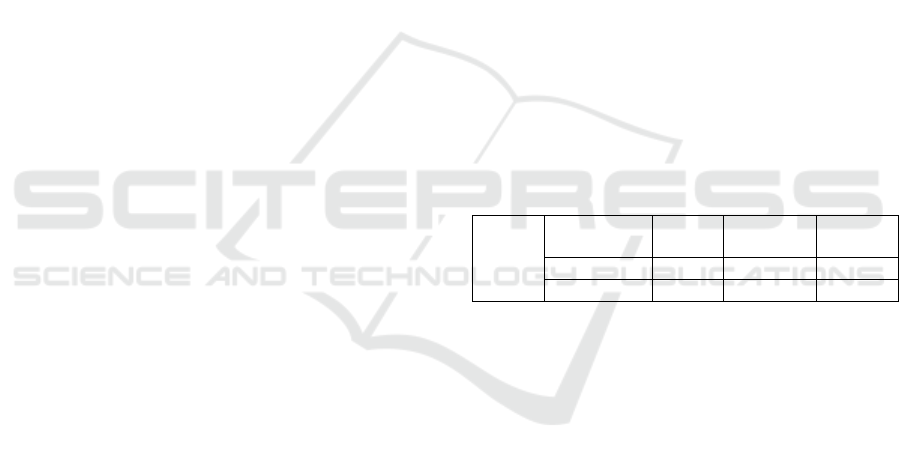

Table 1: Relationship between Socio-Demographic

Factors and KMC Practice.

Age

KMC

practice

N Mean SD

Bad 22 29,26 7,17

Good 8 36,50 4,04

Based on Mann-Whitney U-test, it was found

that age had a statistically significant relationship

with KMC practice among mothers who had LBW’s

babies (z=-2,263, p value<0,05, CI 95%).

4 DISCUSSION

This study showed the practice of KMC after

LBW’s babies’ mothers discharge from hospital and

factors associated with it. All of them were practiced

KMC at home and the mean duration of KMC

practice was 3 hours a day. But none of LBW’s

babies’ mothers who practiced KMC continuously

for 24 hours a day. This study is similar to another

research in Ghana (Opara, PI & Okorie, 2017), in

which none of the mothers carried out KMC

continuously after being discharged from the

hospital. The practice of KMC in the community

was also reported from other studies, which showed

that LBW’s babies’ mothers accepted the method for

Socio-demographic Factors and Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) Practice among Mothers Who Had Low Birth Weight’s Babies in Cilincing

Village, Jakarta

221

the treatment of their LBW’s babies (Opara, PI &

Okorie, 2017; Rasaily et al., 2017)

Based on the observation, the majority of LBW’s

babies’ mothers in this study was practiced KMC

inadequately. The correct position of KMC is that

there is a direct skin-to-skin contact between mother

and baby, the baby's head is turned left or right with

a slight nape, and the baby's hands and feet are bent

like a frog. However, the majority of LBW’s babies’

mothers in this study was practiced KMC with the

position neither the baby's head was not turned left

or right with the position of a slight look, nor the

hands and feet of the baby in a bent position like a

frog.

This study is consistent with a study in India

(Ramaiah, 2016) that the majority of mothers had

moderate practices of KMC (76.66%) and others had

good practices (23.33%). The practice was

correlated with the mother’s knowledge that the

majority of them had a lack of knowledge (65%).

Based on Mann-Whitney U-test, it was found

that age had a statistically significant relationship

with KMC practice among mothers who had LBW’s

babies. In this study, younger mothers were likely to

practice KMC inadequately than older mothers. This

was due to age-associated with the information and

knowledge that the mother has. Older mothers are

more open, had received health information, and

experienced related to health practices. This will

affect a mother's decision to perform an action. The

more mature mothers, the more mature their minds

to act.

Behavior is a response to the stimulus which

influenced by many factors, including personal

characteristics. Factors influencing behavior divided

into internal factors and external factors. Internal

factors are factors that come from within the person,

such as age, sex, etc., and the external factors come

from outside the person, such as physical, social,

cultural, economic, political and other environments

(Notoatmodjo, 2007).

Similarly, another theory (Green, 1999) said that

behaviors are determined by three groups of factors,

namely predisposing factors that include individual

knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, traditions, social

norms and other elements contained within

individuals and communities; enabling factors that is

availability of health services and facilities; and

reinforcing factors that are health worker attitudes

and behaviors.

This study is consistent with the Theory of

Reasoned

(Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010) that behavior is

determined by the intention which influenced by

external variables such as socio-demographic

characteristics including age. Therefore, age was one

of the background factors indirectly related to

behavior.

Based on Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura,

1962), socio-structural is one of the factors that

influence behavior. The theory is based on the belief

that behavior results from continuous interactions

among environment, individual and behavior.

Another theory from the Health Belief Model

(Rosenstock, 1974) discusses that personal

characteristic including age is modifying factors

who will modify individual perceptions that will

affect behavior.

This study is consistent with another study in

Ethiopia (Yusuf et al., 2018) that maternal age was

associated with the utilization of KMC practice, in

which mothers aged 25-29 years old were likely to

practice KMC than mothers aged 30-34 years old.

The study also showed that maternal status, maternal

occupational, educational status, gestational age, and

the number of deliveries were not associated with

the utilization of KMC practice (p>0,05). Similar to

another study in India (Ramaiah, 2016) that socio-

demographic factors including age were related to

knowledge and KMC practice.

The result of this study is inconsistent with study

in Sudan (Meseka et al., 2017), where socio-

demographic characteristics were not related to

knowledge and newborn care practice, including

skin-to-skin contact. Similar to another study in

Nepal (Chaudhary et al., 2018) that type of family,

place of living, religion, age, occupation, and

monthly income were not related to knowledge and

KMC practice.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study showed that age had a statistically

significant relationship with KMC practice among

mothers who had LBW’s babies in Cilincing village,

Jakarta. The need for support from family, health

workers, and community to increase KMC practice

among LBW’s babies’ mothers at home.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the North Jakarta Health

Office, for granting us permission to conduct this

research, and the Education Fund Management

Institution, the Ministry of Finance, the Republic of

ICOH 2019 - 1st International Conference on Health

222

Indonesia, and the Directorate of Research and

Community Engagement of Universitas Indonesia,

who provided funding for this research.

REFERENCES

Ballot, D. E. et al. (2012) ‘Developmental outcome of

very low birth weight infants in a developing country’,

BMC Pediatrics, 12(11). doi: doi:10.1186/1471-2431-

12-11.

Bandura, A. (1962) ‘Social learning through imitation’, in

Nebraska symposium on motivation. Nebraska:

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. doi:

10.1007/978-90-481-9066-9_3.

Bergh, A. et al. (2018) ‘Progress in the Implementation of

Kangaroo Mother Care in 10 Hospitals in Indonesia’,

Journal of Tropical Pediatrics\, 58(5), pp. 402–405.

doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmr114.

Charpak, N. et al. (2017) ‘Twenty-year Follow-up of

Kangaroo Mother Care Versus Traditional Care’,

Pediatrics, 139(1), p. e20162063. doi:

0.1542/peds.2016-2063.

Charpak, N. and Ruiz-pela, J. G. (2000) ‘Kangaroo

Mother Versus Traditional Care for Newborn Infants’,

100(4).

Chaudhary, S., Gauro, P. and Bhattarai, J. (2018)

‘Knowledge regarding Kangaroo Mother Care among

Antenatal Mothers’, International Journal of

advanced research in Science, Engineering and

Technology, 5(10), pp. 7016–7022. Available at:

www.ijarset.com.

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I. (2010) Predicting and Changing

Behavior The Reasoned Action Approach. 1st edn,

Psychology Press. 1st edn. New York. doi:

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203838020.

Green, Lawrence W., M. W. K. (1999) Health Promotion

Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach,

3rd ed. 3rd edn. Edited by M. O’Neill. Canada:

McGraw-Hill/Ryerson Canada.

Lawn, J. E. et al. (2015) ‘Global report on preterm birth

and stillbirth (1 of 7): definitions, description of the

burden and opportunities to improve data’, 10(Suppl

1).

Maraš, N., Polanc, S. and Kočevar, M. (2010) ‘Synthesis

of aryl alkyl ethers by alkylation of phenols with

quaternary ammonium salts’, Acta Chimica Slovenica,

57(1), pp. 29–36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0076.

Meseka, L., Mungai, L. and Musoke, R. (2017) ‘Mothers’

knowledge on essential newborn care at Juba Teaching

Hospital, South Sudan.’, South Sudan Medical

Journal, 10(3), pp. 56–59.

NL Sloan, E. Pinto Rojas, C Stern, L. W. L. C. (1994)

‘Kangaroo mother method: randomised controlled trial

of an alternative method of care for stabilised low-

birthweight infants’, Lancet, 344(8925), pp. 782–785.

doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92341-8.

National Population and Family Planning Board (2013)

Indonesian Demography and Health Surveys 2012,

Sdki. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01580x.

Nguah, S. B. et al. (2011) ‘Perception and Practice of

Kangaroo Mother Care after Discharge from Hospital

in Kumasi, Ghana: A Longitudinal Study’, BMC

Pregnancy and Childbirth. BioMed Central Ltd, 11(1),

p. 99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-99.

Notoatmodjo, S. (2007) Promosi Kesehatan & Ilmu

Perilaku. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta.

Opara, PI & Okorie, E. (2017) ‘Kangaroo mother care:

Mothers experiences post discharge from hospital’,

Journal of Pregnancy and Neonatal Medicine, 1(1).

Pushpamala Ramaiah, A. M. B. M. (2016) ‘A study to

determine the knowledge and practice regarding

Kangaroo mother care among postnatal mothers of

preterm babies at rural centres in India’, J Nurs Care,

5(4), p. 4172. doi: Pushpamala Ramaiah et al., J Nurs

Care 2016, 5:4(Suppl) http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2167-

1168.C1.020.

Quasem, I. et al. (2003) ‘Adaptation of Kangaroo Mother

Care for Community-based Application’, Journal of

Perinatology, 23(8), pp. 646–651. doi:

10.1038/sj.jp.7210999.

Rasaily, R., Ganguly, M. Roy, S. N. Vani, N. Kharood, R.

Kulkarni, S. Chauhan, S. S. & and Kanugo, L. (2017)

‘Community based kangaroo mother care for low birth

weight babies: A pilot study’, Indian J Med Res,

145(November), pp. 163–174. doi:

10.4103/ijmr.IJMR.

Rosenstock, I. (1974) ‘Historical Origins of the Health

Belief Model’, Health Education & Behavior, 2(4),

pp. 328–335. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.873363.

The https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200403.

Soleimani, F., Zaheri, F. and Abdi, F. (2014) ‘Long-Term

Neurodevelopmental Outcomes After Preterm Birth’,

Iran Red Crescent Med J., 16(6), p. e17965. doi:

10.5812/ircmj.17965.

WHO (2003) Kangaroo Mother Care: A Practical Guide,

WHO. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70336-6.

Yusuf, E. et al. (2018) ‘Utilization of Utilization of

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) and Influencing

Factors Among Mothers and Care Takers of

Preterm/Low Birth Weight Babies in Yirgalem Town,

Southern, Ethiopia’, Diversity & Equality in Health

and Care, 15(2), pp. 87–92. doi: 10.21767/2049-

5471.1000160.

Socio-demographic Factors and Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) Practice among Mothers Who Had Low Birth Weight’s Babies in Cilincing

Village, Jakarta

223