The Comparison of Widal Titer in Healthy Individuals Living in

Good and Poor Sanitation Environment in Langsa City, Aceh

Province, Indonesia

Leni Afriani

1*

, Yosia Ginting

2

, Ricke Loesnihari

3

1

Tropical Medicine Program, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Jl. Dr. Mansyur No.5 Medan 20155,

Medan, Indonesia.

2

Division of Tropical and Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Haji Adam Malik General Hospital, Medan,

Indonesia

³Departement of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia.

Keywords: Typhoid, Salmonella, Sanitation, Widal Test, Indonesia

Abstract: Widal test is one of the diagnostic tools used to establish typhoid fever. However, the test may show false

positive particularly among healthy individuals living in a poor sanitation environment. The aim of this

study is to compare the titer of Widal test among healthy individuals living with good or poor sanitation. A

total of 180 healthy individuals resided in Langsa City were enrolled in the study between March and May

2018. Sanitation status of each individual was recorded, assessed and classified into good or poor sanitation.

Of these, 90 and 90 individuals were defined as having good and poor sanitation, respectively. The

proportion of positive Widal titer on Salmonella typhi O was 66.7% (60/90) in individuals with good

sanitation and 61.1% (55/90) among individuals with poor sanitation (P>0.05). However, conversion of S.

Typhi H was more frequent among healthy individuals living with poor sanitation (OR 3.348, 95 % CI =

1

.

754-6.390). We conclude that the sanitation level increased the antibody titers in the Widal test, and

therefore Widal test has limited use to diagnose typhoid fever. Further study is needed to evaluate

behavioral risk factors associated with increased Widal titer and the cut-off level for Widal titer in

population in Langsa City.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the most common infectious diseases in

developing countries is typhoid fever. In 2003, the

World Health Organization (WHO) estimated

around 17 million cases of typhoid fever worldwide

with an incidence of 600.000 deaths every year.

Based on data from Basic Health Research in

Indonesia (RISKESDAS) in 2007, the prevalence of

typhoid fever in Indonesia reached 1.7%. However,

there is no report about typhoid prevalence in

RISKESDAS 2013. The highest prevalence was in

children aged 5-14 years (1.9%), followed by aged

1-4 years (1.6%), 15-24 years (1.5%) and ages less

than 1 year (0.8%). According to the WHO data

published in 2014 it is estimated that there are

around 21 million cases of typhoid fever worldwide

with death reaching 222 thousand people

(Masitoh

2009; Elisabeth 2016; WHO 2014). Data from

Langsa City General Hospital showed that from

2016 to 2018, typhoid fever was one of the top ten

diseases in hospitalized patients, which were

902(11%), 801(12%), and 1113(15%) cases,

respectively (Langsa City General Hospital Profile

2016-2018).

Typhoid fever is an acute systemic infectious

disease caused by gram-negative bacteria

Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi (Salmonella

typhi), a quick and precise diagnosis is needed as

early as possible in suspected patients having

typhoid fever in order to get the right treatment

immediately. Widal test is a modality which is often

used to diagnose typhoid fever (Putri Satwika 2016)

due to an easy, inexpensive, and relatively

noninvasive procedure which can be used as a

diagnostic value where blood culture is not available

(Alam et al 2011). The Widal test diagnostic value

is to address a significant increase of antibody titers

in blood against O (somatic) and H (flagellar)

antigen S. typhi. However, Widal test has a low

146

Afriani, L., Ginting, Y. and Loesnihari, R.

The Comparison of Widal Titer in Healthy Individuals Living in Good and Poor Sanitation Environment in Langsa City, Aceh Province, Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0009862201460151

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease (ICTROMI 2019), pages 146-151

ISBN: 978-989-758-469-5

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

sensitivity and specificity, also have limitations in

interpreting the results, with many false positive and

false negative results due to the prevalence of basic

healthy titers in certain endemic or geographical

regions and sanitary conditions (Wardana et al 2014;

Jemilohun 2017; Chauhan 2016).

Data from the Langsa City Health Profile in 2014

reported one of the indicators of good environmental

condition was community-based total sanitation

(STBM). The number of villages implementing

STBM in Langsa Barat District is 100%, while in

Langsa Timur District 37.5%

(Langsa City Public

Health Department, 2014). Seeing the indicators of

environmental conditions that have not met the

requirements, it will be more likely the healthy

person will have positive results, thus when the

person had a fever, diagnostic errors often occur

(false positive). Therefore we want to assess the

difference in Widal titers of healthy individuals who

live in good sanitation compared to in poor

sanitation environments.

2 METHODS

This was an analytic observational study with a

cross-sectional design. This study was conducted in

Langsa City, located in Langsa Timur and Langsa

Barat District, from March to May 2018. The

samples were healthy individuals aged >18 years

who lived in environments with good sanitation

characteristics in Langsa Barat district and poor

sanitation characteristics in Langsa Timur district.

The initial assessment used an observation sheet on

basic environmental sanitation according to the

Minister of Health Decree No. 829 / Menkes / SK /

VII / 1999, covering assessment including clean

water facilities, latrines (sewage disposal facilities),

wastewater disposal facilities and waste disposal

facilities, with a total assessment of > or = 334

categorized as good sanitation criteria and <334 as a

poor sanitation criteria. A total sample of 180 people

was enrolled. Data collection used purposive

sampling method. Populations that meet the

inclusion criteria are subjects in good health, not

suffering fever (normal body temperature 36.5ºC -

37.2ºC), aged >18 years and residing in Langsa

Barat and Langsa Timur District. While the

exclusion criteria were subjects who were not

willing to take blood samples and participate in the

study.

Widal serological tests were performed on blood

samples from all study subjects to observe the

occurring agglutination

(Agarwal et al 2016), using

the "AIM" brand reagents which consisted of;

Antigen S. typhi H, S. paratyphi AH Antigen, S.

paratyphi BH Antigen, S. paratyphi CH Antigen, S.

Typhi O Antigen, S. paratyphi AO Antigen, S.

paratyphi BO Antigen and S. paratyphi CO Antigen.

All samples were taken directly to the Langsa City

General Hospital Laboratory for examination. The

procedure was carried out in accordance with the

Standard Operating Procedure of the Widal

examination at the Langsa City General Hospital

Laboratory.

Data processing using Statistical Package for the

Social Science (SPSS) version 22.0 was presented

descriptively to see the proportion of Widal titers of

healthy individuals in good environmental sanitation

and poor environmental sanitation. Analysis using

Chi-Square Test and Odds Ratio with significance

level p <0.05 and 95% confidence interval to assess

the relationship of risk factors with positive Widal

results.

This study has been approved by the Ethics

Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Universitas

Sumatera Utara with ethical clearance No. 158 /

DATE / KEPK FK USU-RSUP HAM / 2018.

3 RESULTS

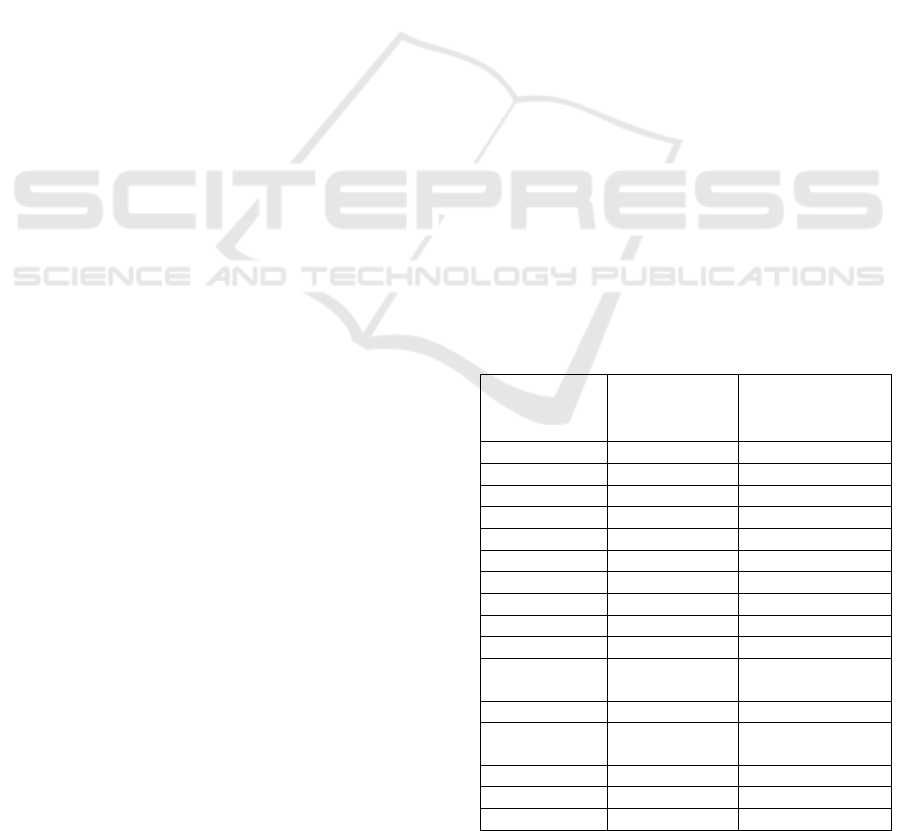

There was no difference in the age group between

the two study groups. Most of the participants were

educated until high school in both groups, 38 people

(42.2%) in the poor sanitation group and 48 (53.3%)

in the good sanitation group (see Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic characteristic of research subjects.

Demographic

Characteristi

c

Poor

Sanitation

(=90)

Good Sanitatio

n

(n=90)

Sex, n (%)

Man 28 (31.1) 33 (36.7)

Woman 62 (68.9) 57 (63.3)

Age, n (%)

< 20 year 3 (3.3) 1 (1.1)

20-29 year 17 (18.9) 20 (22.2)

30-39 year 28 (31.1) 20 (22.2)

40-49 year 16 (17.8) 17 (18.9)

50-59 year 16 (17.8) 21 (23.3)

≥ 60 year 10 (11.1) 11 (12.2)

Education, n

(%)

Uneducated 4 (4.4) 0

PS*

undergraduate

6 (6.7) 4 (4.4)

PS 11 (12.2) 6 (6.7)

JHS** 22 (24.4) 2 (2.2)

SHS*** 38 (42.2) 29 (32.2)

The Comparison of Widal Titer in Healthy Individuals Living in Good and Poor Sanitation Environment in Langsa City, Aceh Province,

Indonesia

147

University 9 (10) 48 (53.3)

Occupation, n

(%)

Housewife 40 (44.4) 19 (21.1)

Unemployed

2(2.2) 3 (3.3)

Entrepreneur

13 (14.1) 30 (33.4)

Student 4 (4.4) 4 (4.4)

Farmer 26 (28.9) 0

Civil

Servant

5 (5.6) 34 (37.8)

*primary school, **junior high school, ***senior high

school

Conversion for Widal test was most occurred for

S. Typhi O in 115 people (63.9%), followed by

conversion for S. Typhi H in 64 people (35.6%).

While the smallest numbers of positive results in

Widal was for agglutinin S. paratyphi 35 people

(19.4%) (see Table 2).

Table 2 Widal test result from overall research subjects.

Agglutinin

Positive

(>1/80)

Negative (< or =

1/80)

S.thypi O, n (%) 115 (63.9) 65 (36.1)

S.parathypi AO,

n (%)

57 (31.7) 123 (68.3)

S.parathypi BO,

n (%)

60 (33.3) 120 (66.7)

S.parathypi CO,

n (%)

47 (26.1) 133 (73.9)

S.thypi H, n (%) 64 (35.6) 116 (64.4)

S.parathypi A H,

n (%)

35 (19.4) 145 (80.6)

S.parathypi B H,

n (%)

36 (20) 144 (80)

S.parathypi CH,

n (%)

37 (20.6) 143 (79.4)

According to the study group, the conversion for

Widal test in the good sanitation group was for S.

thypi O as many as 60 people (66.7%), followed by

S. parathypi agglutinin AO as many as 33 people

(36.7%) The smallest positive results were 13 people

(14.4%) on agglutinin S. paratyphi B H (see Table

3).

Table 3 Comparison of Healthy Individual Widal Titer in

Good Sanitation Environment in Langsa City.

Agglutinin

Positive (>

1/80)

Negative (< or

=1/80)

S.typhi O 60 (66.7) 30 (33.3)

S.paratyphi A O 33 (36.7) 57 (63.3)

S.paratyphi B O 30 (33.3) 60 (66.7)

S.paratyphi C O 32 (35.6) 58 (64.4)

S.typhi H 20 (22.2) 70 (77.8)

S.paratyphi A H 15 (16.7) 75 (83.3)

S.paratyphi B H 13 (14.4) 77 (85.6)

S.paratyphi C H 16 (17.8) 74 (82.2)

While in the poor sanitation group, the agglutinin

conversion was more likely to occur in S. Typhi O

(55 people, 61.1%), followed by agglutinin S. typhi

H as many as 44 people (48.9%), and the least likely

to occur in agglutinin S. Paratyphi CO in 15 people

(16.7%) on (see Table 4).

Table 4 Comparison of Healthy Widal Individual Titer in

Poor Sanitation Environment in Langsa City.

Agglutinin

Positif ( >

1/80 )

Negative ( < atau =

1/80 )

S.typhi O 55 (61.1) 35 (38.9)

S.paratyphi A O 24 (26.7) 66 (73.3)

S.paratyphi B O 30 (33.3) 60 (66.7)

S.paratyphi C O 15 (16.7) 75(83.3)

S.typhi H 44 (48.9) 46 (51.1)

S.paratyphi A H 20 (22.2) 70 (77.8)

S.paratyphi B H 23 (25.6) 67 (74.4)

S.paratyphi C H 21 (23.3) 69 (76.7)

In Langsa Barat district, the highest percentage

of S. Typhi O agglutinin was 1/320 titer in 42 (46%)

subjects. Whereas in East Langsa Timur District, S.

Typhi O agglutinin titers were obtained with the

highest percentage was 1/80 titers in 35 (38.9%)

subjects (see Table 5).

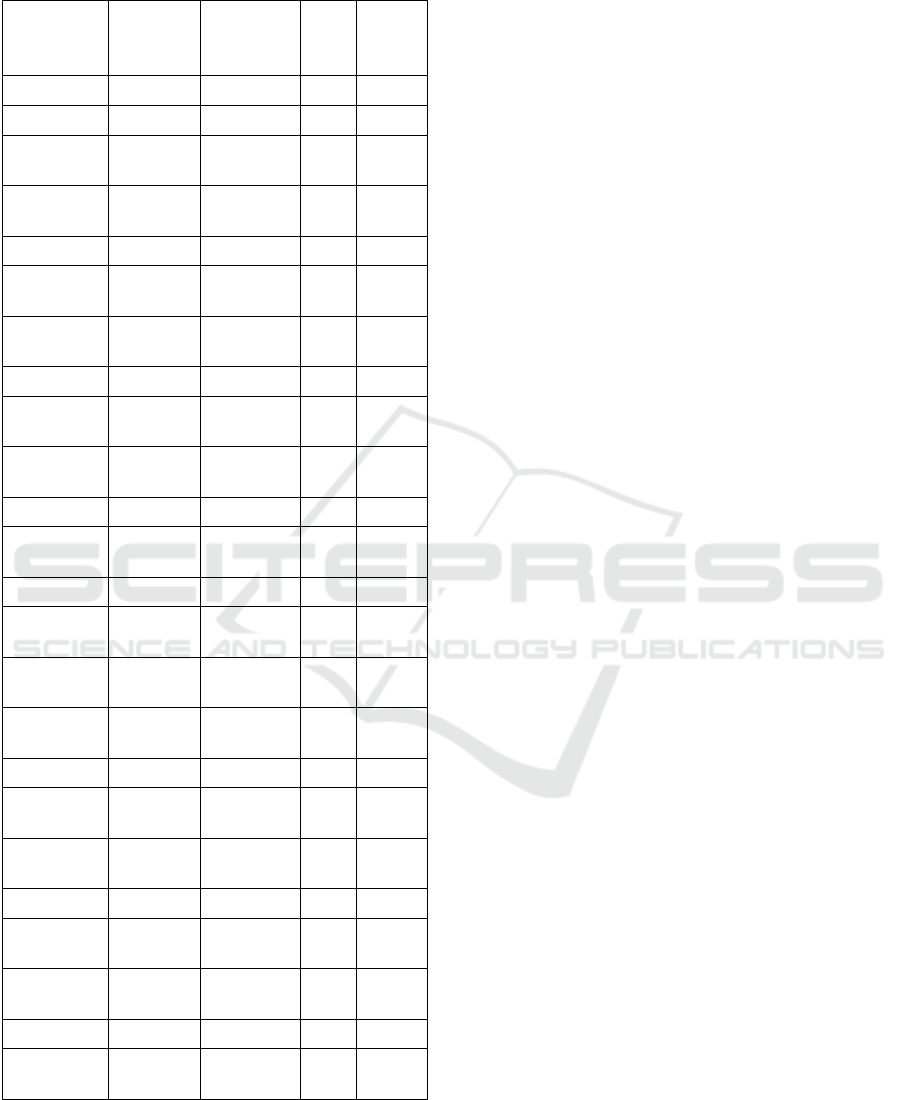

Analysis of the Widal test results between the

subjects who live in the area with good and poor

sanitation are presented in table 6. People living in

poor sanitation were more likely to show agglutinin

S. typhi H (OR = 3.348, 95% CI, P<0.001), S.

paratyphi A H (OR = 1.429, 95% CI, P<0.346), S.

paratyphi B H (OR = 2.033, 95% CI, P<0.062), S.

paratyphi C H (OR = 1.408, 95% CI, P<0.356).

ICTROMI 2019 - The 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease

148

Table 5 Percentage of Widal Titer in the Good Sanitation and Poor Sanitation Area in Langsa City.

Agglutinin

Good Sanitation (n=90) Poor Sanitation (n=90)

1/80 1/160 1/320 1/80 1/160 1/320

S. Typhi O, n(%) 30(33.3) 18(20) 42(46.7) 35(38.9) 34(37.8) 21(23.3)

S. paratyphi AO, n(%) 57(63.3) 22(24.4) 11(12.2)

66(73.3)

18(20) 6(6.7)

S. paratyphi BO, n(%) 60(66.7) 20(22.2) 10(11.1)

60(66.7)

25(27.8) 5(5.6)

S. paratyphi CO, n(%) 58(64.4) 19(21.1) 13(14.4)

75(83.3)

12(13.3) 3(3.3)

S. Typhi H, n(%) 70(77.8) 8(8.9) 12(13.3)

46(51.1)

24(26.7) 20(22.2)

S. paratyphi AH, n(%) 75(83.3) 10(11.1) 5(5.6)

70(77.8)

9(10) 11(12.2)

S. paratyphi BH, n(%) 77(85.6) 8(8.9) 5(5.6)

67(74.4)

15(16.7) 8(8.9)

S. paratyphi CH, n(%) 74(82.2) 11(12.2) 5(5.6) 69(76.7) 11(12.2) 10(11.1)

4 DISCUSSION

Our study showed there is an influence of the level

of sanitation on the results of S. Typhi H. agglutinin

test, where individuals living in poor sanitation was

more likely to have positive results compared to

individuals living in a good sanitation environment.

This result is in line with other studies which have

described the results of Widal test rely on sanitary

conditions, the prevalence of basic titers of healthy

residency in certain endemic and geographical

regions

(Wardana et al 2014; Jemilohun 2017;

Chauhan 2016).

Poor environmental sanitation and health

conditions affect the yield of high titers. In addition,

several factors such as nutritional condition at the

time of test, prior administration of antibiotics,

immunological status, vaccination, use of

immunosuppressive drugs, cross-reaction with other

Enterobacteriaceae and Widal test methods used

also affect the results. These factors are not further

evaluated in this study. The increase in titer of

agglutinin H alone without an increase in agglutinin

O should not be used to diagnose typhoid fever

(Zorgani et al 2014), but may help in diagnosing

suspected typhoid fever in adult patients from non-

endemic areas or in children less than 10 years old in

endemic area, due to the possibility of contact with

S. Typhi in subinfection doses. Thus, if Widal is still

needed to support the diagnosis of typhoid fever, the

threshold for referral titers, both in children and

adults, needs to be determined

(Gaikwad et al 2014).

Widal results on 180 total blood samples from

the study subjects showed an agglutination reaction

between antibodies with Widal antigen. Widal tests

were considered positive if the antibody titer is

1/160 (Loho et al 2000), both for agglutinin O and H

with single or combined diagnostic criteria if a

single criterion is used. Furthermore, agglutinin O is

also found to be more diagnostic than agglutinin H

(Zorgani et al 2014). In this study, we found more

than 50% of the healthy individuals studied were

positive for Widal test (titer>1/80). This is in line

with Chauhan's (2016) study in Uttar Pradesh, India

that among 250 healthy individuals who were

performed Widal test, 56.8 % of them showed a titer

of 1/80 for anti-0 and anti-H antibodies, leading to

set this titer as the baseline titer for diagnosing

typhoid fever

(Chauhan 2016). Having known the

titer for the conversion of Widal test among our

population in Langsa, we set up a titer of 1/80

against antibody H to be used for the diagnosis of

typhoid fever.

Based on the results of Widal test of healthy

individuals in the two sanitation area groups, the

most frequent positive test result was for agglutinin

S. thypi O in 60 people (66.7%) in good sanitation

and in 55 people (61.1%) in poor sanitation. This

shows that Salmonella agglutinin is generally found

in individuals who appear to be healthy and not

suffering from fever when having their blood

examined in different populations and sanitation. It

also concluded that the Widal test is easy to

applicate but has limitations in endemic areas,

including Indonesia

(Suryani et al 2018). Therefore,

if the Widal test is still needed to support the

diagnosis of typhoid fever, the threshold for

reference titers for both children and adults needs to

be determined

(Zorgani et al 2014).

The Comparison of Widal Titer in Healthy Individuals Living in Good and Poor Sanitation Environment in Langsa City, Aceh Province,

Indonesia

149

Table 6 Differences in Widal Test Results Based on

Environmental Sanitation Conditions.

Agglutinin

Poor

Sanitation

n=90

Good

Sanitation

n=90

Ρ OR

95%CI

S. typhi O

Positive 55 (61.1) 60 (66.7) 0.438 0.786

Negative 35 (38.9) 30 (33.3)

0.427-

1.446

S. paratyphi

A O

Positive 24 (26.7) 33 (36.7) 0.149 0.628

Negative 66 (73.3) 57 (63.3)

0.333-

1.184

S. paratyphi

B O

Positive 30 (33.3) 30 (33.3) 1.000 1.000

Negative 60 (66.7) 60 (66.7)

0.538-

1.859

S. paratyphi

C O

Positive 15 (16.7) 32 (35.6) 0.004 0.363

Negative 75(83.3) 58 (64.4)

0.180-

0.732

S. Typhi H

Positive 44 (48.9) 20 (22.2)

<0.00

1

3.348

Negative 46 (51.1) 70 (77.8)

1.754-

6.390

S. paratyphi

A H

Positive 20 (22.2) 15 (16.7) 0.346 1.429

Negative 70 (77.8) 75 (83.3)

0.679-

3.008

S. paratyphi

B H

Positive 23 (25.6) 13 (14.4) 0.062 2.033

Negative 67 (74.4) 77 (85.6)

0.956-

4.325

S. paratyphi

C H

Positive 21 (23.3) 16 (17.8) 0.356 1.408

Negative 69 (76.7) 74 (82.2)

0.679-

2.916

Our study also showed the highest value of

agglutinin was at 1/320, this was also reported in

another study by Bahadur and Peerapur (2013) in

healthy individuals in Karnataka, India

(Bahadur et

al 2013). Thus, if the same Widal titer obtained from

patients with suspected typhoid fever who seek

treatment at health care facilities in Langsa City,

relying on Widal as the only diagnostic laboratory

test of typhoid fever will generate a misleading

diagnosis, with a false positive possibility. When

blood culture is compared to the Widal test for the

diagnosis of typhoid fever, the specificity of the

Widal test reduced significantly. Of 270 individuals

with suspected typhoid fever and positive O and H

antibodies, 74.4% were negative in blood culture

and only small proportion was positive for S. Typhi

(N=7, 2.6%) and S. paratyphi (N=1.5%) (Andualem,

2014). Therefore, it is very important to do more

accurate tests such as culture to confirm typhoid

fever.

5 CONCLUSION

This study showed there was an increase in Widal

titers of healthy individuals in good and poor

sanitation environment in Langsa City. Healthy

individuals living in poor sanitation environment

were at risk of having 3.348 times positive S. Typhi

Widal titers compared to healthy individuals living

in good sanitation environment. Widal test,

therefore, can give a false-positive interpretation in

the diagnosis of typhoid fever and should be used

with other tools with better specificity. There are

limitations in this study, particularly in factors

related to high yield titer. Further study is needed to

evaluate behavioral risk factors associated with

increased Widal titer and the cut-off level for Widal

titer in population in Langsa City.

REFERENCES

Agarwal Y, Gupta D, Sethi R. Enteric Fever: Resurrecting

the epidemiologic footprints. Astrocyte.

2016;3(3):153-61.

Alam ABM, Rupam FA, Chaiti F. Utility of a single

Widal test in the diagnosis of typhoid fever.

Bangladesh J Child Health. 2011;35(2):53-58

Andualem G, Abebe T, Kebede N, Gebre-Selassie S,

Mihret A. A comparative study of Widal test with

blood culture in the diagnosis of Typhoid fever in

febrile patients. BMC Res Notes. 2014 Sep;7(1): p.

653. Available at:

https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/eum/article/view/1768

1. [Cited 2018 March].

ICTROMI 2019 - The 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease

150

Bahadur AK, Peerapur B V. Baseline titer of Widal

amongst healthy blood donors in Raichur, Karnataka.

JKIMSU. 2013;2(2):30–6.

Chauhan S. Study of baseline Widal titer amongst

apparently healthy individuals in and around

Muzaffarnagar City of Uttarpradesh, India.

International Journal of Pharma and BioSciences.

2016 Feb;7(1):p.152–155.

Dinas Kesehatan Kota Langsa. 2014. Profil kesehatan

Kota Langsa tahun 2014. Langsa: Dinas Kesehatan

Kota Langsa

Elisabeth Purba I, Wandra T, Nugrahini N, Nawawi S,

Kandun N. Program pengendalian demam tifoid di

Indonesia: tantangan dan peluang. Media Penelitian

dan Pengembangan Kesehatan [Internet].

2016;26(2):99–108. Available from:

http://ejournal.litbang.kemkes.go.id/index.php/MPK/ar

ticle/view/5447

Gaikwad UN, Rajurkar M. Diagnostic efficacy of Widal

slide agglutination test against Widal tube

agglutination test in enteric fever. Int J Med Public

Health. 2014 Jul;4(3):227-30

Jemilohun AC. How useful is the Widal test in modern

clinical practice in developing countries? A review.

IJTDH. 2017;26(3):1-11

Loho T, Sutanto H, Silman E. In: Demam tifoid peran

mediator, diagnosis, dan terapi (Editor: Zulkarnain).

Pusat Informasi dan Penerbitan bagian Ilmu Penyakit

Dalam. 2000:22-42

Masitoh D. Hubungan antara perilaku higiene

perseorangan dengan kejadian demam tifoid pada

pasien rawat inap di Rumah Sakit Islam Sultan

Hadlirin Jepara Tahun 2009. Skripsi. UNNES. 2009

June;1:58-65.

Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Kota Langsa. 2018. Profil

RSUD Kota Langsa Tahun 2016-2018. Langsa:

Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Kota Langsa

Putri Satwika, Anak Agung; Lestari, A.A. Wiradewi. Uji

diagnostik tes serologi Widal dibandingkan dengan tes

IgM Anti Salmonella Typhi sebagai baku emas pada

pasien suspect demam Tifoid di Rumah Sakit Surya

Husadha pada bulan Januari sampai dengan Desember

2013. E-Jurnal Medika Udayana. 2016 Jan;1:1-18

Suryani DY. Shodikin MA, Astuti IS. Widal titre among

healthy population in University of Jember. E-Jurnal

Pustaka Kesehatan.2018 May;6(2):245-250

Wardana IMTN, Herawati S, Yasa IWPS. Diagnosis

demam Typhoid dengan pemeriksaan Widal. E-Jurnal

Med Udayana. 2014;3(2):237-50.

WHO. WHO International. [Online].; 2014 [cited 2018

March. Available from:

www.wpro.who.int/philippines/typhoon_haiyan/media

/Typhoid_fever.pdf.

Zorgani A, Ziglam H. Typhoid fever: misuse of Widal test

in Libya. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8(6):680-687

The Comparison of Widal Titer in Healthy Individuals Living in Good and Poor Sanitation Environment in Langsa City, Aceh Province,

Indonesia

151