The Impact of High Performance Work Systems (HPWSs) on

Organizational Performance by the Roles of Job Design

Shaira Ismail

1

, Baderisang Mohamed

1

and Dahlan Abdullah

2

1

Faculty of Business and Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Cawangan Pulau Pinang

2

Faculty of Hotel Management and Tourism, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Cawangan Pulau Pinang

Keywords:

High Performace Work System (HPWS), Job Design, Job Analysis, Job Specification, Skill, Knowledge and

Abilities (SKAs).

Abstract:

The changing nature of the ‘job’ has gained an increasing attention to examine the nature and substance of jobs

and its impact on organizational performance. This paper aims to examine the relationship between organi-

zational performance and job design in the manufacturing sector. The survey questionnaire was administered

to the different categories of managerial level in the manufacturing firms in Kuala Lumpur and Northern Re-

gion through email and in person. The questionnaire consists of factors like; organizational performance, job

design, job description, job specification and job analysis. The study is quantitative research approach. The

collected data reveal that organizational performance and job design are positively related with each other.

This study also shows that job design is a powerful tool to enhance organizational performance and could be

considered as one of the HPWS components.

1 INTRODUCTION

The technology advancement in the workplace,

changing in workforce, population demographics,

customers preference and competition environment

put a pressure on organizations to develop strategies

to maintain its competitiveness in the marketplace. It

requires to establish a strategic job analysis in ensur-

ing jobs are critically relevant in the workplace. As

defined by (Brannick and Levine, 2002)) the job anal-

ysis is an organized process whereby the nature of a

job is divided and established. The job related in-

formation and other related tasks and qualifications

are the core functions in the human resource man-

agement (HRM) perspectives. The job analysis plays

a vital role. It has an impact on the HR functions

and significantly linked to the organizational perfor-

mance (Bowin and Harvey, 2001). (Dessler, ) rec-

ognized on a strong Human Resource–Performance

linkage for those organizations that are systematically

implementing job analysis as a human resource strat-

egy where they perform better with gain more in terms

of benefits as compared to those who are not. By

treating workers with respect and as capable and intel-

ligent individuals, organizations find that workers are

more committed to the organization and more trustful

of management, which will result in improved perfor-

mance (Walton, 1985) .

The job analysis provides job-related informa-

tion and determines the employee’s skills, knowl-

edge and abilities (SKAs) to perform certain job ac-

tivities. Most of the researchers concluded that job

analysis is a backbone and the cornerstone of the

human resource practices (Huselid, 1994), (Huselid,

1995); (Delaney and Huselid, 1996) and enhance job

retention, organizational performance and productiv-

ity. There are a few indicators of organizational per-

formance such as human resource outcomes, organi-

zational outcomes, financial or accounting outcomes

and stock-market performance indicators as well as

every part of product performance as explained by

(Stankard, 2002). The job analysis output is a job

description which outlines the job tasks, duties and

responsibilities in relation to the technical and non-

technical aspects of the job, its title, job summary, job

duties, tasks and outputs. It is a written statement of

the tasks to be performed by employees. As (Byars

and Rue, 1984) further described, job description is

a written narrative of the tasks to be performed and

what it entails. Whereas, job specification is a writ-

ten statement of qualifications, traits or behavioural

perspectives needed by the tasks as well as physical

and mental characteristics should be possessed by an

individual to perform the job duties and responsibili-

242

Ismail, S., Mohamed, B. and Abdullah, D.

The Impact of High Performance Work Systems (HPWSs) on Organizational Performance by the Roles of Job Design.

DOI: 10.5220/0009867902420248

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Creative Economics, Tourism and Information Management (ICCETIM 2019) - Creativity and Innovation Developments for Global

Competitiveness and Sustainability, pages 242-248

ISBN: 978-989-758-451-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

ties. (Gatewood et al., 2015) concluded that the tasks

and employee attributes of an assigned job are con-

sidered as worker-oriented or work oriented. This

has led many scholars to examine the ways ‘jobs’ are

created and designed to make it more open towards

the continuous change in the workplace. The orga-

nization should ensure that jobs are continuously re-

designed to keep them at pace with the changing in

technology and other environmental factors. Job de-

sign has been expanded in the empirical studies re-

cently (Parker et al., 2001) (Morgeson et al., 2012).

The job design research initiated by (Hackman et al.,

1975) through the development of Job Characteristics

Model (JCM). The JCM‘s components of skill mul-

tiplicity, task distinctiveness, tasks implications, self-

sufficiency and job feedback are positively related to

employee motivation and high job performance.

It has been concluded that an integrated approach

used by firm in managing their employees has a sig-

nificant impact on firm performance (Becker et al.,

1997) (Wright and Boswell, 2002) based on the the-

oretical perspectives (Lado and Wilson, 1994) (Jack-

son and Schuler, 1995)and empirical studies (Huselid,

1995) (MacDuffie, 1995). These integrated HRM

practices have an impact on employees’ performance

in improving their skills, attitudes and commitment,

which empowered them to make a good decision

while performing their tasks (Batt, 2002) (Datta et al.,

2005) (Guthrie, 2001). These practices yield employ-

ees‘ capabilities and subsequently have a positive in-

fluence on organizational performance. These HRM

practices able to sustain the organizational core com-

petencies, its people and crucially important for the

effective implementation of the organizational strat-

egy (Pfeffer, 2005).

2 LITERATURE REVIEWS

2.1 High Performance Work Systems

(HPWSs)

The high-performance work systems (HPWSs) are

the integration of innovative and interactive human

resource management (HRM) practices or in other

term, it is a bundle of HRM practices that contribute

significantly to the firm better performance (Huselid,

1995). Researchers have proven that there is a posi-

tive link between HPWSs and organizational perfor-

mance (Appelbaum et al., 2000) ; (Arthur, 1994);

(Guthrie, 2001) ; (Youndt et al., 1996). High perfor-

mance work systems (HPWSs) have been associated

with the employees and organizational high job per-

formances. The HPWSs enhance employees’ poten-

tial by improving their knowledge, skills and abilities

(KSAs), motivation and commitment and eventually

producing a high quality of performance (Appelbaum

et al., 2000) ; (Huselid, 1995); (Youndt et al., 1996).

Previous empirically studies had identified a broad

component of HRM practices in association to the

HPWSs. Those practices are employment of em-

ployees (recruitment and selection), financial and

non-financial compensation, flexible work schedule,

communication amongst the group members, per-

formance appraisal, training and development pro-

vided by employers, their commitment and innova-

tion, employment security, career development, or-

ganizational structure, policies, procedures and prac-

tices, employee involvement and participation, pro-

motion, grievance procedure and status distinction ac-

cording to the position hold by employees (Arthur,

1994) ; (Baer and Frese, 2003); (Becker et al., 1998) ;

(Boxall and Macky, 2007) ; (Chow, 2005) ; (Guthrie,

2001) ; (Huselid, 1995); ((Ichniowski et al., 1995) ;

(MacDuffie, 1995). It is concluded that, the HPWSs

are a set of integrated HRM practices.

It has been a lack of consensus pertaining to which

HPWSs contribute to financial performance (Huselid

et al., 1997), in the aspect of firm productivity

(Guthrie, 2001) to employee commitment (Whitener,

2001), absenteeism (Guest and Peccei, 1994) and cus-

tomer satisfaction (Rogg et al., 2001). Due to the ex-

istence of vast differences in such measures, the ag-

gressive debates about the relationship between high

performance work practices and firm performance oc-

curred (Wright and Snell, 1998); (Guest, 1997); (Ger-

hart et al., 2000) on the causal relationships between

these variables and linkages of HPWSs to employee

outcomes and as well as to the organizational perfor-

mance.

2.2 Job Design

The first major theory with respect to the job design

constructed by Herzberg and his colleagues (Herzberg

et al., 1959) where they distinguish between two

types of factors, namely motivators (e.g. achieve-

ment, recognition, and responsibility), and hygiene

factors (e.g. work conditions, pay, and supervision).

According to Hertzberg’s theory, a challenging job

lead to higher achievement, recognition, advancement

and growth amongst employees. Most of studies into

work design theory is centred on the Job Characteris-

tics Model (JCM) by (Hackman and Oldham, 1980) .

The job design would help organizations and employ-

ees to survive in the turbulent marketplace (Hackman

et al., 1975). The job characteristics approach to job

The Impact of High Performance Work Systems (HPWSs) on Organizational Performance by the Roles of Job Design

243

design is the most widely recognized model devel-

oped by (Hackman et al., 1975) as per Figure 1. This

model contributes to a certain level of psychological

states and employees’ need for growth. The critical

psychological states can be summarized in the three

conditions. Firstly, the cognitive state is where em-

ployees perceive their valuable work contributions are

crucial for the organization. Secondly, is the responsi-

bility of employees, how they feel personally account-

able for the work they do and its results. The next

degree is when employees have an ability to under-

stand how effective they are in performing their jobs,

that is the results or outputs they produce. The job

enrichment (JE), job engineering (JEng), quality of

work life (QWL), socio-technical designs, the social

information processing approach (SIPA) and the job

characteristics are a variety of job design approaches.

Figure 1: Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model

(1976)

2.3 Job Design and Organizational

Performance

As indicated by (Loher et al., 1985) there is a posi-

tive relationship between job characteristics and job

satisfaction and a high level of individual growth

need strength (GNS). A study conducted by (Mor-

rison et al., 2005) further proven that job designs

lead to a high level job control amongst the employ-

ees and provides opportunities for the skills enhance-

ment. In addition, the job design approach leads to

high level of productivity through the perceived work

demands by employees, job control and social sup-

port (Love and Edwards, 2005). (Sokoya, 2000) con-

cluded that a combination of jobs, work and personal

characteristics contribute to the high level of job sat-

isfaction through the implementation of job rotation

amongst managers of different jobs. This job design

approach adds the benefit of task variety and increases

the employees’ performance. It was then further

proven by (Bassy, 2002) that skills, task identity, task

significance, autonomy, feedback, job security and

compensation are the important determinants of em-

ployee motivation. Empirical studies have established

that jobs and goal setting can enhance performance

through a job design approach. A well designed jobs

have a positive impact on employees’ satisfaction and

the quality of performance. The job design in associ-

ation to an expanded job characteristics, its outcomes

in improving motivation, enhancing learning and de-

veloping organizations, innovation/creativity towards

a high performance environment contribute directly to

organizational outcomes, individual/group outcomes

and social outcomes (Garg and Rastogi, 2006).

The high-performance work practices (HPWSs)

contribute successfully in improving the organiza-

tional performance by having a mutual communica-

tion and integrating tasks amongst the employees to

carry out their tasks and responsibilities. It is sup-

ported by (Bowen and Ostroff, 2004) that human re-

source practices contribute positively to the firm per-

formance by integrating work practices and intensi-

fying its adoption to a high level of degree across

all relevant employee functions. The job design is

able to build a systematic, symbiotic, task-induced,

and high performance environment. Empirical stud-

ies have indicated that well designed jobs positively

have an impact on both employee satisfaction and the

quality of performance. Thus, it is proposed that a

job design would improve the employees working be-

haviour and simultaneously contribute to the firm bet-

ter performance. The employees work commitments

and efforts are the strength of high-performance work

practices. These notions lead to the development of

Hypothesis 1;

Hypothesis 1. The job design has a positive im-

pact on firm performance

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This study aims to examine the relationship of or-

ganizational performance and job design. The re-

search instrument is a survey questionnaire, which

comprised of three sections; Section A is on corporate

profile data, Section B is related to demographic data

and Section C is statements related to the job design

and its relationship with organizational performance.

The research study involved respondents in different

categories of managerial level; Chief Executive Of-

ficers (CEOs), Human Resource Directors/Managers

and Operation Managers of the manufacturing firms

in Kuala Lumpur and Penang to complete a survey

questionnaire, which asked them questions about their

perceptions of the High Performance Work Systems

(HPWSs) components of job design and their impacts

on firm performance, and a series of questions rele-

vant to respondents’ biodata and corporate profile.

The survey questionnaire was administered

through email and in person. A total of 1500

ICCETIM 2019 - International Conference on Creative Economics, Tourism Information Management

244

questionnaires was delivered and emailed to those

manufacturers (MNCs and local manufacturing firms)

in Kuala Lumpur and Northern Region. For manufac-

turers located in Penang, some of the questionnaires

were delivered personally. The convenience sampling

technique was used. The sampling list of firms,

local manufacturing firms and MNCs were obtained

from the Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC).

Presently, there are 2000 manufacturing firms (i.e.

SMEs, large firms) including MNCs registered with

MPC. The sampling covers large manufacturing firms

with an employment of more than 500 employees.

The large local manufacturing firms and MNCs

represent 25% of the list. The percentage of respon-

dents involved is 420 respondents and considered

as “reasonably representative” of the population

organizations.

The respondents were asked about their percep-

tions based on 7 Likert-type scales from Strongly Dis-

agree (1) to Strongly Agree (7) on the job design and

organizational performance. For other measurements

of organizational characteristics comprise of organi-

zation size (i.e. number of workforce) and the com-

pany’s ownership, the respondents furnished the fac-

tual data of their firms. The firm performance mea-

surements were based upon the respondents’ percep-

tual judgment of the current performances of the firms

associated with profitability level, productivity index

and market growth with a range from (1) Above In-

dustry Level; (2) Average Industry Level; (3) Below

Industry Level and (4) At Par with other Industry

Level. They were also required to estimate the per-

centage of perceived organizational performance on

those performance indicators. These respondents are

more likely to have wide experience and knowledge

in human resource management policy and practices.

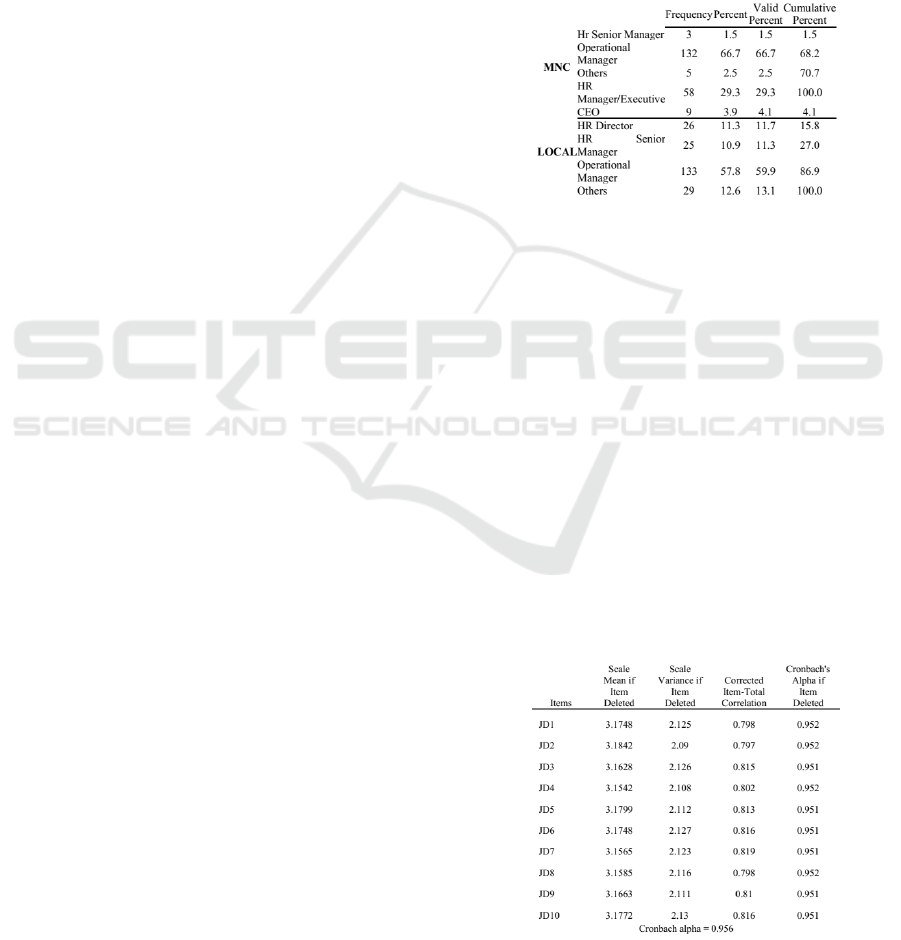

3.1 Respondents Profile

The majority of respondents is an operation manager

from MNC and local company in Malaysia. Com-

pared to local company, MNC appeared to have more

respondents from the HR manager/ executive. Since

most of the respondents were from the managerial po-

sitions and they have been actively involved in com-

pany operations and decision making, which shall en-

sure the reliability of the responses in reflecting the

company they represented.

Figure 2: Descriptive statistic for position by type of com-

pany.

4 FINDINGS

4.1 Reliability of Job Design

Figure 3 reports the Cronbach alpha reliability out-

put for job design dimension, which has 10 indica-

tors (measurement variables). Based on the table, the

Cronbach alpha value of 0.926, which is higher than

the 0.7 cut off point, suggesting that this dimension

exhibited a good construct/ dimension reliability. In

addition, all of the variables showed high corrected

item-total correlation, hence no item should be omit-

ted.

Figure 3: Cronbach alpha for Job Design.

The Impact of High Performance Work Systems (HPWSs) on Organizational Performance by the Roles of Job Design

245

4.2 Reliability of Firm Performance

Figure 4reports the Cronbach alpha reliability output

for firm performance dimension, which has 8 indica-

tors (measurement variables). Based on the table, the

Cronbach alpha value of 0.946 is higher than the 0.7

cut off point, indicating that this dimension exhibited

a good construct/ dimension reliability. In addition,

all of the variables showed high corrected item-total

correlation, hence no item should be omitted.

Figure 4: Cronbach alpha for Firm Performance.

4.3 Relationship Between Job Design

and Firm Performance

Based on the Figure 5, clearly the path was significant

with a p value smaller than 0.05. Findings showed

that, the job design had significant impact on the firm

performance (FP) at 0.05 significance level. The pos-

itive BETA value tells that the job design factor has a

positive impact on firm performance. In other words,

with the implementation of job design-JD, the firm

will likely result in higher performance.

Figure 5: Regression Weight of direct effect.

5 CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this paper, it has been focused on the role of job de-

sign as a critical component of the High Performance

Work Systems and its impact on organizational out-

comes. The job design is one of the most effective

approach to enhance employee performance. There

are various approaches of design jobs to boost up em-

ployee motivation, increase productivity and enhance

organizational growth. An implementation of the ef-

fective job design requires management to look at

what aspects of the jobs are important and how it fits

with the organizational goals. Thus, the main purpose

of implementing the job design is to diagnose what is

needed for the job and job holders. The HR managers

should play a critical role in instilling the perceptions

of jobs and create competitive and strategic jobs by

increasing levels of engagement and responsibilities

and developing positive perceptions of the job design.

The implication of this research work is, the organisa-

tions should consider orchestrating jobs with an em-

phasis on creating variety in people’s work, providing

them with autonomy in the decisions as well as devel-

oping enriched and strategic jobs.

Future research should consider the relationship

between the strategic jobs and organizational perfor-

mance as jobs itself is the cornerstone of the HR prac-

tices. It should explore the effect of the strategic jobs

in that link between organizational performance, in-

dividual outcomes with a mediating variable of job

analysis. Thus, for both academicians and practition-

ers, creating a strategic job is vital in today’s hu-

man resource management system to capitalise the

human potentials in increasing their intrinsic moti-

vation, SKAs and work performance, and simultane-

ously improve the performance of an organization to

effectively compete in the global marketplace

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thanks Universiti Teknologi MARA,

Cawangan Pulau Pinang for the assistance and finan-

cial support rendered towards the production of this

paper

ICCETIM 2019 - International Conference on Creative Economics, Tourism Information Management

246

REFERENCES

Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., Kalleberg, A. L., and

Bailey, T. A. (2000). Manufacturing advantage: Why

high-performance work systems pay off. Cornell Uni-

versity Press.

Arthur, J. B. (1994). Effects of human resource systems on

manufacturing performance and turnover. Academy of

Management journal, 37(3):670–687.

Baer, M. and Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough:

Climates for initiative and psychological safety, pro-

cess innovations, and firm performance. Journal of

Organizational Behavior: The International Journal

of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psy-

chology and Behavior, 24(1):45–68.

Bassy, M. (2002). Motivation and work-investigation and

analysis of motivation factors at work.

Batt, R. (2002). Managing customer services: Hu-

man resource practices, quit rates, and sales growth.

Academy of management Journal, 45(3):587–597.

Becker, B. E., Huselid, M. A., Becker, B., and Huselid,

M. A. (1998). High performance work systems and

firm performance: A synthesis of research and man-

agerial implications. In Research in personnel and

human resource management. Citeseer.

Becker, B. E., Huselid, M. A., Pickus, P. S., and Spratt,

M. F. (1997). Hr as a source of shareholder value: Re-

search and recommendations. Human Resource Man-

agement: Published in Cooperation with the School of

Business Administration, The University of Michigan

and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources

Management, 36(1):39–47.

Bowen, D. E. and Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding hrm–

firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength”

of the hrm system. Academy of management review,

29(2):203–221.

Bowin, R. B. and Harvey, D. (2001). Human resource man-

agement: An experiential approach. Pearson Higher

Education.

Boxall, P. and Macky, K. (2007). High-performance work

systems and organisational performance: Bridging

theory and practice. Asia Pacific Journal of Human

Resources, 45(3):261–270.

Brannick, M. T. and Levine, E. L. (2002). Job analysis:

Methods, research, and applications for human re-

source management in the new millennium.

Byars, L. L. and Rue, L. W. (1984). Human resource and

personnel management. RD Irwin.

Chow, I. H.-S. (2005). High-performance work systems in

asian companies. Thunderbird International Business

Review, 47(5):575–599.

Datta, D. K., Guthrie, J. P., and Wright, P. M. (2005).

Human resource management and labor productivity:

does industry matter? Academy of management Jour-

nal, 48(1):135–145.

Delaney, J. T. and Huselid, M. A. (1996). The impact of hu-

man resource management practices on perceptions of

organizational performance. Academy of Management

journal, 39(4):949–969.

Dessler, G. Human resource management, 2003. Pearson

Prentice Hall ISBN, 13(127677):8.

Garg, P. and Rastogi, R. (2006). New model of job design:

motivating employees’ performance. Journal of man-

agement Development.

Gatewood, R., Feild, H. S., and Barrick, M. (2015). Human

resource selection. Nelson Education.

Gerhart, B., Wright, P. M., and McMahan, G. C. (2000).

Measurement error in research on the human re-

sources and firm performance relationship: Fur-

ther evidence and analysis. Personnel Psychology,

53(4):855–872.

Guest, D. E. (1997). Human resource management and

performance: a review and research agenda. In-

ternational journal of human resource management,

8(3):263–276.

Guest, D. E. and Peccei, R. (1994). The nature and causes of

effective human resource management. British Jour-

nal of Industrial Relations, 32(2):219–242.

Guthrie, J. P. (2001). High-involvement work prac-

tices, turnover, and productivity: Evidence from

new zealand. Academy of management Journal,

44(1):180–190.

Hackman, J. R., Oldham, G., Janson, R., and Purdy, K.

(1975). A new strategy for job enrichment. California

Management Review, 17(4):57–71.

Hackman, J. R. and Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign.

Huselid, M. (1994). Documenting hr’s effect on company

performance. HR MAGAZINE, 39:79–79.

Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource man-

agement practices on turnover, productivity, and cor-

porate financial performance. Academy of manage-

ment journal, 38(3):635–672.

Ichniowski, C., Shaw, K., and Prennushi, G. (1995). The

effects of human resource management practices on

productivity. Technical report, National bureau of eco-

nomic research.

Jackson, S. E. and Schuler, R. S. (1995). Understanding

human resource management in the context of orga-

nizations and their environments. Annual review of

psychology, 46(1):237–264.

Lado, A. A. and Wilson, M. C. (1994). Human re-

source systems and sustained competitive advantage:

A competency-based perspective. Academy of man-

agement review, 19(4):699–727.

Loher, B. T., Noe, R. A., Moeller, N. L., and Fitzgerald,

M. P. (1985). A meta-analysis of the relation of job

characteristics to job satisfaction. Journal of applied

psychology, 70(2):280.

Love, P. E. and Edwards, D. J. (2005). Taking the pulse of

uk construction project managers’ health. Engineer-

ing, Construction and Architectural Management.

MacDuffie, J. P. (1995). Human resource bundles and

manufacturing performance: Organizational logic and

flexible production systems in the world auto industry.

ilr Review, 48(2):197–221.

Morgeson, F. P., Garza, A. S., and Campion, M. A. (2012).

Work design. Handbook of Psychology, Second Edi-

tion, 12.

The Impact of High Performance Work Systems (HPWSs) on Organizational Performance by the Roles of Job Design

247

Morrison, D., Cordery, J., Girardi, A., and Payne, R. (2005).

Job design, opportunities for skill utilization, and in-

trinsic job satisfaction. European journal of work and

organizational psychology, 14(1):59–79.

Parker, S. K., Wall, T. D., and Cordery, J. L. (2001). Future

work design research and practice: Towards an elabo-

rated model of work design. Journal of occupational

and organizational psychology, 74(4):413–440.

Pfeffer, J. (2005). Seven practices of successful. Operations

Management: A Strategic Approach, page 224.

Rogg, K. L., Schmidt, D. B., Shull, C., and Schmitt, N.

(2001). Human resource practices, organizational cli-

mate, and customer satisfaction. Journal of manage-

ment, 27(4):431–449.

Sokoya, S. K. (2000). Personal predictors of job satisfac-

tion for the public sector manager: Implications for

management practice and development in a develop-

ing economy. Journal of business in developing na-

tions, 4(1):40–53.

Stankard, M. F. (2002). Management systems and organiza-

tional performance: The search for excellence beyond

ISO9000. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Walton, R. E. (1985). From Control to Commitment in the

Workplace: In factory after factory, there is a revo-

lution under way in the management of work. US

Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor-Management

Relations and Cooperative . . . .

Whitener, E. M. (2001). Do “high commitment” human

resource practices affect employee commitment? a

cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear model-

ing. Journal of management, 27(5):515–535.

Wright, P. M. and Boswell, W. R. (2002). Desegregating

hrm: A review and synthesis of micro and macro hu-

man resource management research. Journal of man-

agement, 28(3):247–276.

Wright, P. M. and Snell, S. A. (1998). Toward a unifying

framework for exploring fit and flexibility in strategic

human resource management. Academy of manage-

ment review, 23(4):756–772.

Youndt, M. A., Snell, S. A., Dean Jr, J. W., and Lepak, D. P.

(1996). Human resource management, manufacturing

strategy, and firm performance. Academy of manage-

ment Journal, 39(4):836–866.

ICCETIM 2019 - International Conference on Creative Economics, Tourism Information Management

248