A Rare Case of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis: Recognition of

Distinctive Clinical and Histopathological Signs

Sarah Mahri

1*

, Lidwina Anissa

1

, Rinadewi Astriningrum

1

, Githa Rahmayunita

1

,

Triana Agustin

1

, Rahadi Rihatmadja

1

1

Department of Dermatology and Venereology Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia/

Dr. CiptoMangunkusumo National Central General Hospital, Indonesia

Keywords: Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, clinical signs, histopathology

Abstract: Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatosis with a prevalence of

1:100,000 to 1:300,000.Mutations primarily of keratin 1 or keratin 10 cause defective keratinization, leading

to skin fragility, blistering, and hyperkeratosis. Neonates with EHK are at risk of developing electrolyte

imbalance, sepsis and malnutrition leading to a considerable mortality. Therefore its diagnosis is important.

As the clinical features of EHK become more apparent with age, a wide spectrum of other genodermatosis

should be considered as differentials at different stages of the disease process. A 5-year-old boy presented to

our department with dirty brown, corrugated plaques distributed all over his body. He had had history of

trauma-related blistering since two days after birth. As he aged, there was a decrease in development of

blisters and erosions, with accompanying increase in severity of hyperkeratosis and foul odor. Physical

examination revealed thickened, brown plaques over the neck, trunk, extremities, and scalp. Cobblestone

pattern were visible over the knees, elbows, and posterior of hands and feet, in addition to multiple

superficial erosions. Histopathologic examination showed massive hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis,

lysis and clumping of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum to granulosum. The diagnosis of EHK was

made. Vaseline, coconut oil, and antiseptic soap gave slight, but acceptable improvement. EHK is rare, thus

recognizing its distinctive clinical patterns is necessary to avoid delayed diagnosis and gave necessary

genetic counselling and prompt treatment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK), also known as

bullous congenital ichthyosi form erythroderma is an

autosomal dominant trait with a prevalence of

approximately 1 in 100,000 to 300,000 persons.

1-

4

The disease is named for the distinctive

histopathologic feature of vacuolar degeneration and

associated hyperkeratosis of the epidermis.

4

EHK is caused by mutations in keratin 1 or keratin

10, resulting in subsequent skin cell collapse and

fragility. This clinically manifests as blistering, later

followed by hyperkeratosis and hyper proliferation.

Onset typically occurs in newborn, with generalized

erythroderma. Erosions, blisters, and peeling are

present. Although the blistering and erythema often

improve over time, hyperkeratotic scale becomes

prominent, most commonly over the neck, hands,

feet, and joints. Other affected areas include the

scalp and infragluteal folds.

1-4

Neonates with EHK

are at risk of developing sepsis,electrolyte

imbalance, and malnutrition leading to a

considerable mortality, therefore its diagnosis is

important.

Between 2016-2018 there were no cases of

epidermolytic hyperkeratosis in our institution. We

herein report a rare case of epidermolytic

hyperkeratosis in a 5-year-old boy. The purpose of

this report is to familiarize with its characteristic

features that enable clinician to make early diagnosis

and distinction with other ichthyosis and bullous

diseases of childhood, as well as to discuss the

therapeutic possibilities.

2 CASE

A 5-year-old boy was consulted to our clinic with

dirty brown, corrugated hyperkeratotic plaques

Mahri, S., Anissa, L., Astriningrum, R., Rahmayunita, G., Agustin, T. and Rihatmadja, R.

A Rare Case of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis: Recognition of Distinctive Clinical and Histopathological Signs.

DOI: 10.5220/0009985902570261

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease (ICTROMI 2019), pages 257-261

ISBN: 978-989-758-469-5

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

257

distributed all over his body beginning two years

before.

The history started two days after birth, when he

developed blisters on his trunk and extremities,

which ruptured and became eroded. Lesions recurred

over his whole body, sparing the palms, soles, and

face. Blisters and erosions usually healed leaving

hyperpigmentation without scarring. Although he

continued to develop erythema and blisters, they

decreased in severity and frequency with age.

Superficial erosions ceased few months after his

birth and followed by hyperkeratosis lesions.

By the age of three, the patient developed

generalized hyperkeratosis and scaling over his

trunk, extremities and scalp. The lesions

occasionally became pruritic. He would scratch and

peel the affected skin and sometimes they became

infected. As hyperkeratosis became more

pronounced, so did the foul odor. The disease did

not appear to involve the nail or impair neurological

functions.

He has a history of hyper IgE and delayed

speech. He is the only child of healthy, non-

consanguineous parents. No family history of similar

disorders and no history of restrictive membrane at

birth.

Thickened, brown, dirty corrugated plaques were

found on physical examination, distributed over the

neck, trunk, extremities, and scalp, affecting

approximately 95% of his body surface area.

Cobblestone pattern were visible over the knees,

elbows, and posterior of hands and feet. Areas of

superficial erosion were evident on his left ear, back,

upper and lower limbs. His scalp hair were enclosed

in thick whitish scales.(Figure 1-3).

Figure 1. Clinical manifestation. A. Face is spared B. Whitish thick scales on the scalp C,D. Dirty brown, corrugatedplaques

over the trunk along with areas of superficial erosion.

A

B

C

D

ICTROMI 2019 - The 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease

258

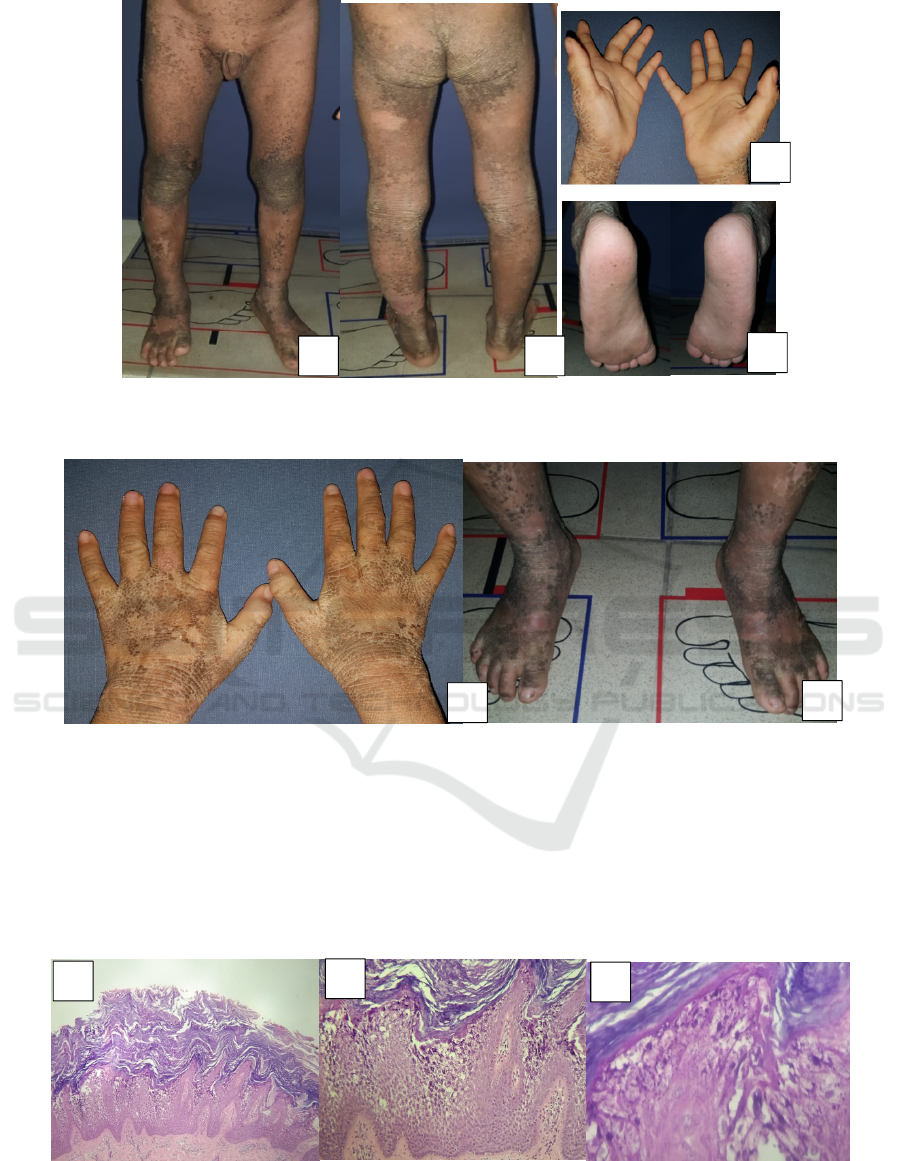

Figure 2. Clinical manifestation. A,B. Hyperkeratotic warty plaques widely spread over the lower limb with areas of

superficial erosion C,D. Sparing palms and soles

Figure 3.Cinical manifestation. A,B. Dirty brown, cobblestone, hyperkeratotic plaques over the posteriorof hand and feet

Histopathology from an area of hyperkeratosis

on his left knee showed massive hyperkeratosis,

acanthosis of stratum malpighi, spongiosis, lysis and

clumping of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum

to stratum granulosum. Lymphocytic cells are seen

around blood vessels. The findings were consistent

with EHK. (Figure 4 A-C)

On the basis of clinical and histopathological

feature epidermolytic hyperkeratosis was diagnosed.

The patient was treated with vaseline, coconut oil for

scalp, and antiseptic soap. The patient was consulted

to paediatrician, opthalmologist and dentist.

Figure 4.Routine histopathology (haematoxylin-eosin) revealed massive hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiosis (A,B)

and lysis and clumping of keratinocytes (C)

A

C

B

A B

C

D

A

B

A Rare Case of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis: Recognition of Distinctive Clinical and Histopathological Signs

259

3 DISCUSSION

Our case was presented with classical symptoms and

signs of EHK: dirty brown, corrugated

hyperkeratotic plaques distributed all over the body,

with history of trauma-related blistering a few day

after birth that decrease by the age only to be

subsequently replaced by malodorous

hyperkeratosis. This clinical description is

characteristic. Brocq first described EHK in 1902,

and coined the term bullous ichthyosiform

erythroderma, to distinguish it from the non-

blistering condition, congenital ichthyotic

erythroderma. It starts at birth with generalized

erythroderma, blisters, and peeling with even mild

trauma, leading to superficial ulcerations. As the

child grows, the erythroderma and blisters decrease,

and the hyperkeratosis increase. The distinct foul

odor is caused by the bacterial colonization of the

macerated scales.

3

From anamnesis we found that parents were not

affected and so were the rest of the family. He is the

only child of healthy and non-consanguineous

parents. This disease is mostly inherited as an

autosomal dominant trait, albeit 50% of cases result

from spontaneous mutations, and recently an

autosomal recessive inheritance has been reported.

Mutations in keratin 1 and 10 encoding genes,

localized on chromosome 12 and 17, respectively,

are responsible for EHK. Mutations in keratin 1

encoding gene are associated with severe

palmoplantar keratoderma, while mutations of

keratin 10 encoding gene are not.

5

The lack of

palmoplantar involvement in this case suggested that

keratin 10 could be involved.

The histopathologic features of our patient is

consistent with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis with

massive hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, lysis

and clumping of keratinocytes in the stratum

spinsoum to spinosum. The typical histopathologic

features of EHK, which were first described by

Nikolsky in 1897, include acanthosis, marked

hyperkeratosis, coarse keratohyalin granules, and

multiple perinuclear vacuoles present in the upper

spinous layer. Clumping of keratin intermediate

filaments at the suprabasal level can be visualized by

means of electron microscopy, while

immunohistochemistry can show a defect in the

expression of keratin 1 and/or 10.

5

A diagnosis of

EHK is usually made clinically, and can be

confirmed by the presence of typical

histopathological features.

During childhood, EHK can be differentiated

from congenital recessive X-linked ichthyosis on the

basis of the history of blistering and histological

findings. Epidermolytic palmoplanta rkeratoderma is

limited to the palms and soles, whereas ichthyosis

bullosa of Siemens lacks erythroderma, localization

of dark grey hyperkeratosis to the flexural sites, and

areas of peeling of the skin known as the

"Mauserung phenomenon".

5,6

Ichthyosishystrix

Curth-Macklin type patients may look like EHK

patients, but there is no clinical or histological

evidence of blister formation.

5

The patient was treated with vaseline and

coconut oil for thick scales on his scalp, and

antiseptic soap to minimized the foul odor. The

patient was consulted to paediatrician to evaluate the

delayed speech and his general growth and

development, and also to ophtalmologist to evaluate

the involvement of eyes. To evaluate whether he had

dental dysplasia or not, the patient was also

consulted to dentist. Follow up after one month

showed improvement in the hyperkeratotic plaques

and the malodor. Consultations to paediatrician,

opthalmologist and dentist have been done. There

were no abnormalities on his eyes and no dental

dysplasia. The delayed speech was probably caused

by multilingual parents and is not associated with

the disease.

Initial treatment early in disease is targeted

towards symptomatic relief and management of the

secondary complications of the erosions.

5,7,8

These

complications include electrolyte imbalance,

dehydration, infection, and sepsis, especially in

neonates with blisters and erosions. Erosions need to

be managed meticulously with barrier protection and

gentle handling of the skin to minimize the

development of secondary infection. Bacterial

overgrowth, particularly from Staphylococcus

aureus, and an odor can develop as a result of scale

accumulation, which may be controlled with

chlorhexidine or antibacterial cleansers.

5,7,8

Later in

disease, emollients as well as topical and systemic

retinoids can be considered. Topical emollients are

considered mainstay therapy, as well as creams or

ointments that possess keratolytic properties to

reduce the hyperkeratosis scale that develops in

these patients. Examples include urea, alpha-

hydroxy acids, lactic acid, and glycerin, although

lactic acidosis is a concern with topical lactic acid in

infants and small children.

For more severe cases, oral and topical retinoids

have also been shown to improve the skin condition,

although retinoids may promote desquamation and

exacerbate blistering. For unknown reasons,

individuals with keratin 10 gene mutations respond

better to topical or systemic retinoid therapy, as

ICTROMI 2019 - The 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease

260

compared to those with keratin 1 gene

mutations.

5

Although indicated, we didn’t give

retinoids in this patient due to a lack of availability

in Indonesia. After one month followed up, parents

reported improvement, so we decided to continue

the current therapies.

Education is important in this case. After genetic

counseling, we gave the parents and family

information about high protein diet, patient higiene

in order to prevent secondary infection and

minimized malodor, and also how to keep the patient

from overheating because in patients with

ichthyosis, sweating is often inadequate owing to the

occlusion of eccrine ducts. Affected individuals

should be guarded against overheating during winter

months and kept in air-conditioning during warmer

months, with frequent wetting of the skin or even

cooling suits during sports activities.

9

For the prognosis, widespread blistering clears after

newborn period while the hyperkeratotic scale

usually lifelong. Generalized involvement may

improve to localized disease after puberty.

4 CONCLUSION

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is rare and has a

challenging differential diagnosis. Nevertheless, it is

important for clinicians to identify the disease early

in order to reduce morbidity and mortality.

REFERENCES

Fleckman P, DiGiovanna JJ, Elder JT. The Ichthyoses. In:

Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS,

Leffell DJ, Wolff K, Eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in

General Medicine. 8

th

Ed. New York: McGrawHill;

2012. p.507-38.

Spitz, Joel L.Genodermatoses: A Clinical Guide to

Genetic Skin Disorders. 2

nd

Ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. p. 6-9.

Hayashida MT, Mitsui GL, Reis NI, Fantinato G, Neto

DJ, Mercante AMC. Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis -

case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(6):888-91.

Pan K, Chakrabarti S, Choudhury R, Sarkar A, Mitra

R.Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: a rare case. Int J Res

Med Sci. 2014 Feb;2(1):347-9.

Alshami M, Mohana M, Alshami A. Epidermolytic

Hyperkeratosis: A Case Report from Yemen. Invest

DermatolVenerol Res. 2016;2(1):61-3.

Charlene U, Ang-Tiu, Marie Eleanore O,

Nicolas.Ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens. J Dermatol

Case Rep. 2012; 6(3):78-81.

Siavash M, Shanehsaz, Bittar R, Anis A, Ishkhanian S.

Bullous ichthyosiformerythroderma: case presentation.

Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists.

2014;24 (1):86-8.

Millsop JW, Sivamani RK, Lee DC, Konia T,

Subramanian N and Fung MA.A Case of Bullous

Congenital IchthyosiformErythroderma, a Rare

Pediatric Genodermatosis, in a Newborn. Austin J

Dermatolog. 2014;1(4):1016.

Paller A, Mancini AJ. Hurwitz clinical pediatric

dermatology: A textbook of skin disorders of

childhood and adolescence. 5

th

ed. New York:

Elsevier/Saunders; 2016.

A Rare Case of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis: Recognition of Distinctive Clinical and Histopathological Signs

261