Generalized Pustular Psoriasis in Childhood

Milka Wulansari Hartono

1

*, Ernawati Hidayat

1

, Buwono Puruhito

1

, Asih Budiastuti

1

,

Meira Dewi Kusuma Astuti

2

1

Department of Dermatovenereology, Faculty of Medicine, Diponegoro University /

Dr. KariadiGeneral Hospital

2

Department of Pathological Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Diponegoro University /

Dr. Kariadi General Hospital

*

Corresponding auhtor

Keywords: Childhood generalized pustular psoriasis, cyclosporine

Abstract: A Generalized pustular psoriasis is a rare form of psoriasis in children. The prevalence of psoriasis in

children is ≈0.71%, the pustular type occurring in 0.6-7%.It is more severe in children and characterized by

a generalized pustule, forming the lake of pus, on an erythematous base.A 9-year-old boy presented with

fever and sudden onset of pustules eruption on erythematous base over the face, trunk, and extremities.

There was no past or family history of psoriasis. The laboratory result was leucocyte count 14.000/ µL,

CRP1,43 mg/L, qualitative ASTO (+). Histopathologic examination revealed skin lesions with psoriasiform

reactions, microabscess munro (+), dermis contained adnexa of the skin, stroma hyperemia with

lymphocytes, histiocytes, PMN leucocytes, supporting the diagnosis of generalized pustular psoriasis.

Patient was treated with cyclosporine tablet 3 mg/kgbw/day, desoximetasone cream 0,25% twice

daily,loratadine tablet 10 mg/day, paracetamol tablet3x500 mg.Generalized pustular psoriasis often requires

systemic and topical therapy because of the severity of the disease.Cyclosporin is recommended as a first-

line drug for pediatric generalized pustular psoriasis. Cyclosporin acts by inhibiting T-cell and IL-2.

Treatment using oral cyclosporin gave a good outcome in this patient. The eruptions markedly improved

after administration of oral cyclosporine 3 mg/kgbw/day for seven days.Topical treatment using a potent

corticosteroid, which has antiinflammatory and antiproliferative properties were co-administered to

increase the efficacy.Prognosis quo ad vitam ad bonam, quo ad sanam dubia ad bonam dan quo ad

kosmetikamad bonam.

1 INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin

disease,characterized by complex alterationsin

epidermal growth and differentiation (Gudjonsson et

al, 2012; Griffi et al, 2010).

The exact etiology and

pathogenesis is unknown but immunologic

drivenmediated primarily by T cells in the dermis,

genetic andenvironmental factors also are implicated

in the development of the disease (Gudjonsson et al,

2012; Griffi et al, 2010; Voorhees et al, 2019).

Psoriasis is universal in occurrence, affecting 2

to 4% of the world’s population, equally common in

males and females, may begin at any age, but it is

uncommon under the age of 10 years (Saikaly et al,

2016).

The prevalence of psoriasis in children is ≈

0.71%.Many subtypes of childhood psoriasis have

been described, including generalized pustular

psoriasis (GPP), which is arare form, affecting 0,6-

7% of psoriasis patients (Gupta et al, 2015; Bhuiyan

et al, 2017).

Generalized pustular psoriasis is a rare type of

psoriasis first described in 1910 by Von Zumbusch,

and it is the most severe type and can be potentially

life-threatening. It presents abruptly

withconstitutional symptoms and diffuse

erythematous lesions, followed by yellow-colored

sterile pustules.The etiology of pustular psoriasis is

uncertain. Its onset has been associated with

triggering factors such as trauma, infections,

emotional stress, vaccinations, sunlights, metabolic

factors, alcohol and smoking, drugs, and HIV. The

abrupt withdrawal of systemic and topical

corticosteroids and the withdrawal of cyclosporin

have also been implicated (Gudjonsson et al, 2012;

352

Hartono, M., Hidayat, E., Puruhito, B., Budiastuti, A. and Astuti, M.

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis in Childhood.

DOI: 10.5220/0009988603520356

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease (ICTROMI 2019), pages 352-356

ISBN: 978-989-758-469-5

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Griffi et al, 2010; Voorhees et al, 2019; Saikaly et al,

2016; Hoegler et al, 2018).

The pathogenesis of GPP is only partially

understood. GPP can present in patients with

existing or prior psoriasis Vulgaris or in patients

without a history of psoriasis Vulgaris. More than

half of the GPP individual cases are caused by

recessive mutations in IL36RN. IL36RN encodes

interleukin-36-receptor antagonist (IL-36Ra), which

antagonizes three interleukin cytokines (IL-1F6, IL-

1F8, and IL-1F9) that are involved in the activation

of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways (Hoegler et

al, 2018).

The clinical presentation of generalized pustular

psoriasis usually presents with 2-3 mm sterile

pustules overlying painful, erythematous skin.

Patients are visibly ill, with high-grade fever,

malaise, leucocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein

levels (Hoegler et al, 2018). Diagnostic criteria

proposedby Umezama et al. are consisted of 1)

multiple sterile pustules overlying erythematous

skin, 2) fever, malaise and other systemic symptoms,

3) Kogoj spongiform pustules on histopathological

analysis, 4) laboratory abnormalities including left

shift leucocytosis, elevated erythrocyte

sedimentation rate, elevated CRP, elevated ASTO

levels, elevated IgG or IgA levels, hypoproteinemia,

hypocalcaemia, 5) recurrence of these

clinical/histopathological features. (Hoegler et al,

2018) The differential diagnosis of pustular psoriasis

is with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis

(AGEP), but AGEP tends to occur and resolve more

quickly and is particularly associated with antibiotic

use (Hoegler et al, 2018).

For the diagnostic examination, we can do a

biopsy for a histopathology examination. The

histopathology findings in pustular psoriasis consist

of confluent parakeratosis, hyperkeratosis,

neutrophils in stratum corneum (Munro

microabscesses) and in spinous layer (spongiform

pustules of Kogoj), hypergranulosis,sub-

parapapillary thinning of the epidermis, regular

acanthosis, often with clubbed rete ridges, dilated

capillaries in dermal papillae, perivascular

lymphocytes (Rapini, 2012).

A broad spectrum of antipsoriatic treatments,

both topical and systemic, is available for the

management of psoriasis (Gudjonsson et al, 2012).

In patients with erythrodermic and pustular

psoriasis, treatments with acitretin, methotrexate, or

short-course cyclosporine are the treatments of the

first choice (Gudjonsson et al, 2012).

For children

with GPP, first-line treatment is similar to that

inadults.As retinoids can cause premature epiphyseal

closure,skeletal hyperostosis, and extraosseous

calcification, it maynot be ideal first-line therapy.

Cyclosporine has fewer knownsideeffects and is

often the first treatment used before

retinoids.Methotrexate is not approved in children

under the age of 2 years.Both methotrexate and

cyclosporine must be used with cautionbecause of

the long-term oncogenic potential.A recent

retrospective chart review assessed the efficacy of

cyclosporine in pediatric patients having extensive

plaquetype, erythrodermic, and pustular psoriasis.

Excellent efficacy (>75% reduction in PASI) was

observed in all but three patients (Gudjonsson et al,

2012; Rapini, 2012; Dogra et al, 2017; James et al,

2016; Dogra et al, 2018). Corticosteroids shouldbe

utilized with caution, especially in patients with

concomitantpsoriasis Vulgaris because of the

potential to initiate flares.Combination therapies are

employed in almost 50% of the children with

generalized pustular psoriasis in order to provide

optimum disease control. Pustular psoriasis in

children has a more favorable course as compared to

adults. The response to treatment is good, and

remission lasts longer as compared to adults (Dogra

et al, 2018).

2 CASE

A nine-year-oldboy, Indonesian people, Javanese,

was brought by her parents to the dermato-

venereology clinic in Karyadi General Hospital on

August 10

th

, 2018 with a chief complaint ofsudden

onset of pustules eruptions on an erythematous

baseover the face, trunk, and extremities.

The lesions were developed within 24 h after the

patient got vaccinated in his school. The lesion was

initially on his face then became more generalized

with the involvement of the face, trunk, and

extremities. The symptoms were alsoaccompanied

by fever and pain on his body.Then his parents

brought him to a dermatologist. There he received

treatment with topical cream and oral capsule, but

the lessons did not improve, so he was referred to

Karyadi Hospital.

The patient did not suffer from any other

diseases or use any topical or systemic medication

before. He had no food or drug allergy. Therewas no

past and family history of dermatosis, including

psoriasis. The patient was the first child, and he has

a healthy 5-year-old little brother. He was in 2

nd

-

grade junior high school, and his academic status

was functional. His parents worked as an employee.

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis in Childhood

353

The payment method was using BPJS insurance, and

the economic status impression was low.

On the initial physical examination, the patient

was looked ill-appearance, body height: 120 cm and

body weight: 17 kg. He had a fever, t = 38

0

C. He

also had difficulty to walk because of the pain on his

leg. On the dermatology, examination showedtypical

widespreadpustules that developed on an

erythematous base on his face, trunk, and

extremities. (figure 1).

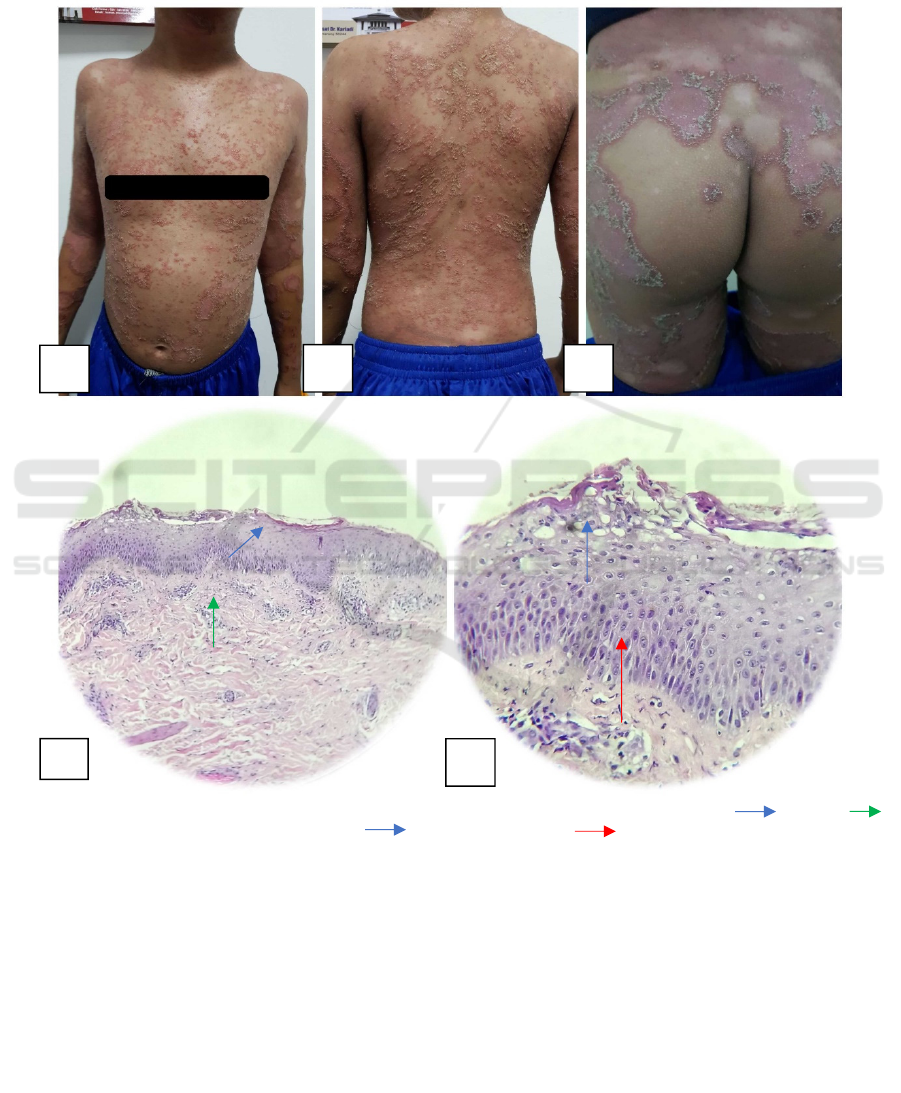

Figure 1. A&B&C. The clinical appearanceof the lesion. D. (i) Histopathology examination showed: parakeratosis,

dermis with lymphocytes and PMN leucocytes E. Munro’s microabsces sAcanthosis

Then we did the laboratory examination, and

there were some abnormality including, leucocyte

count 14.000/ µL, CRP 1,43 mg/L, qualitative

ASTO (+). Histopathologic examination revealed

skin lesions with psoriasiform reactions, Munro's

microabscess (+), dermis contained adnexa of the

skin, stroma hyperemia with lymphocytes,

histiocytes, PMN leucocytes, supporting the

diagnosis of generalized pustular psoriasis. (figure 1)

Based on history taking, physical and

dermatology examination, laboratory and

histopathology examination, the diagnosis of

generalized pustular psoriasis was made. Differential

diagnosis with drug reaction was eliminated.

The patient was treated withcyclosporine tablet 3

mg/kgbw/day, desoximetasone cream 0,25% twice

daily, loratadine tablet 10 mg/day, paracetamol

tablet 3x500 mg. The patient experienced rapid

improvement of his skin lesion. At one week follow

up, the skin had markedly improved. (figure 2)Then

the dosage of cyclosporine was tapered off.

A

B C

D

E

ICTROMI 2019 - The 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease

354

Figure 2. Clinical improvement after one-week administration of cyclosporine and topical desoximetasone Discussion

Diagnosis ofgeneralized pustular psoriasiswas

made based onhistory taking, physical and

dermatology examination, laboratory, and

histopathology examination.

From history-taking, a 9-year-old boy had suddenly

developed widespread pustules on an erythematous

base, 24 hr after he got vaccinated in his school.

There was no past and family history of dermatosis,

including psoriasis, and he also admitted that he did

not use any topical or systemic medication before.

According to the theory, psoriasis is a complex

inflammatory skin condition with abnormal

epidermal keratinocyte differentiation and

hyperproliferation.It is universal in occurrence,

equally common in males and females, may begin at

any age, but it is uncommon under the age of 10

years. The exact etiology and pathogenesis is

unknown but immunologic, genetic, and

environmental factors with triggering factors such as

trauma, infections, emotional stress, vaccinations,

sunlights, metabolic factors, alcohol and smoking,

drugs and HIValso are implicated in the

development of the disease. (Gudjonsson et al, 2012;

Griffi et al, 2010; Voorhees et al, 2019;Saikaly et

al,2016).

From the physical examination, the patient

presented typical widespread pustules that developed

on an erythematous base on his face, trunk, and

extremities, accompanied by constitutional

symptoms such as fever and tenderness on the

lesion. Psoriasis has many clinical patterns of skin

presentation, such as psoriasis vulgaris, guttate

psoriasis, small plaque psoriasis, inverse psoriasis,

erythrodermic psoriasis, pustular psoriasis. Several

clinical variants of pustular psoriasis exist

generalized pustular psoriasis (von Zumbusch type),

annular pustular psoriasis,impetigo herpetiformis,

and two variants of localized )and acrodermatitis

continua of Hallopeau.Generalized pustular psoriasis

is a distinctive acute variant of psoriasis. It is

characterized by fever, and sudden generalized

eruption of pustules arise on erythematous skin. This

form of psoriasis is usually associated with

prominent systemic

signs and can potentially have life-threatening

complications. (Gudjonsson et al, 2012)

A laboratory and histopathological examination

were done. Findings revealed some abnormalities

such asleucocyte count 14.000/ µL, CRP 1,43 mg/L,

qualitative ASTO (+). Histopathologic examination

revealed skin lesions with psoriasiform

reactions,Munro's microabscess (+),dermis

contained adnexa of the skin, stroma hyperemia with

lymphocytes, histiocytes, PMN leucocytes. It is

consistent with generalized pustular psoriasis’

histopathology findings.

The treatment in this patient were usingcyclosporine

tablet 3 mg/kgbw/day(tapered-off after 1 week),

desoximetasone cream 0,25% twice daily, loratadine

tablet 10 mg/day, paracetamol tablet 3x500

mg.According to the theory, combination therapies

are employed in almost 50% of the children with

generalized pustular psoriasis in order to provide

optimum disease control. An initial daily oral

regimen of 2.5 mg/kg cyclosporine equally divided

in two doses has been recommended. Improvement

may be seen within days, but if this does not occur

within two weeks, the dosage may be increased

gradually to a maximum of 5 mg/kg/day.

Maintenance dosage should be reduced to the

minimum that allows adequate control A systematic

review of therapies for severe psoriasis concluded

that ‘cyclosporine is a well-tested treatment for

severe psoriasis and in the short term, ideally 3-4

months, is probably more effective than other forms

of systemic therapy's (Griffi et al, 2010)

Topical corticosteroidwas used in adjunct to

systemic cyclosporine as local therapyto increase the

efficacy, but the duration and the dosage should be

monitored carefully because of the potential

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis in Childhood

355

induction of pustules. The paracetamol and

loratadine herewere used as symptomatic

therapy.(Fujita et al,2018).

In this case report,the patient experienced rapid

improvement of his skin lesion. At one week follow

up, the skin had markedly improved. Prognosis quo

ad vitam ad bonam, quo ad sanam dubia ad bonam

dan quo ad kosmetikamad bonam.

3 CONCLUSION

Generalized pustular psoriasis is a rare form of

psoriasis, and onset at children is even rarer. In this

case report, combination therapies using systemic

cyclosporine and topical desoximetasone, gave a

good outcome. There are many factors influence the

remission and relapse/worsening of this disease, so

despite the therapy, we also provided education for

the patient and her family that his disease was a

chronic disease, and could be triggered with various

factors and to maintain the remission, it needed

cooperation between patient, doctors, and parents.

REFERENCES

Bhuiyan MSI, Zakaria ASM, Haque AKMZ, Shawkat SM,

Sultana A. 2017. Clinico-epidemiological study of

childhood psoriasis. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Med

Univ J. 10(2):119.

Dogra sunil, Bishnoi Anuradha. 2018. Childhood

Psoriasis: What is New and What is News. Indian

Journal of Paediatric Dermatology. 308-14

Dogra S, Mahajan R, Narang T, Handa S. 2017. Systemic

cyclosporine treatment in severe childhood psoriasis:

A retrospective chart review. J Dermatolog Treat.

28(1):18–20.

Fujita H, Terui T, Hayama K, Akiyama M, Ikeda S,

Mabuchi T, et al. 2018. Japanese guidelines for the

management and treatment of generalized pustular

psoriasis: The new pathogenesis and treatment of

GPP. J Dermatol. 45(11):1235–70

Griffi th CEM, Camp RDR HI, Baker J. 2010. Psoriasis.

In: Burn T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffi th C, editors.

Rook’s textbook of dermatology. 8th ed.

Massachussets: Blackwell Publishing. p.351- 69.

Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT. 2012. Psoriasis. In: Wolff K,

Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leff

el DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general

medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill

Companies Inc. p.197-231.

Gupta S, Deo K, Wadhokar M, Tyagi N, Sharma Y. 2015.

Juvenile generalized pustular psoriasis in a 10-year-

old girl. Indian J Paediatr Dermatology. 0(0):0

Hoegler KM, John AM, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. 2018.

Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review and update

on treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol.

32(10):1645–51

James WD, Elston DM, G.Berger T, editors. 2016.

Seborrheic Dermatitis, Psoriasis, Recalcitrant

Palmoplantar Eruptions, Pustular Dermatitis, and

Erythroderma. In: Andrew’s Diseases of The Skin

Clinical Dermatology. twelfth ed. Philadelphia:

Elsevier Inc. 187-95

Rapini RP. 2012. Eczematous and Papulosquamous

Diseases. In : Practical Dermatopathology. 2nd

edition. London: Elsevier Saunders. 52-4

Saikaly SK, Mattes M. 2016. Biologics and Pediatric

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis: An Emerging

Therapeutic Trend. Cureus.8(6).

Voorhees AV, Wanat Karolyn. 2019.

Psoriasis:Erythrodermic and Pustular Variants.

Clinical Advisor Dermatology.

ICTROMI 2019 - The 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease

356