Personas and Tasks for International Data Space-based Ecosystems

Torsten Werkmeister

Technical University Ilmenau, Institute for Media Technology, Germany

Keywords:

Persona, Tasks, User-centered Interaction Design, International Data Space.

Abstract:

The International Data Space (IDS) is a platform developed for a global data ecosystem, composed of inter-

connected devices which gather, process, exchange and trade data. IDS and industry data are the research

focus of many scientific papers dealing with analysis from a technical and economic point of view (Brost

et al., 2018; Graube, 2018). This paper examines the users of the IDS as personas, a method for presenting

and communicating stakeholder needs for IDS. By applying a user picture and name, properties and descrip-

tion a persona provides product users and developers with a representation of the design target. Using this

research approach, the industry-wide requirements of potential users are analyzed in a task-oriented scientific

approach and presented in personas. Applying this task-oriented approach, the new roles and associated new

tasks of this domain are essential, as the people and tasks are extremely risky, hard to access and complex.

The results provide the prerequisites for designing user-centric interfaces for the IDS.

1 INTRODUCTION

The intelligent use of data in IDS enables the creation

of new products, services and the reinforcement of re-

search and development. ”The data value chain is at

the center of the future knowledge economy, bringing

the opportunities of the digital developments to the

more traditional domains (e.g. transport, financial ser-

vices, health, manufacturing, retail)” (European Com-

mission, 2013). In this context data is becoming a

valuable economic and commercial asset.

The IDS

1

is a platform designed for the industry-

wide use, composed of interconnected devices which

gather, process, exchange and trade data. It was initi-

ated and developed by various researchers from eco-

nomics, law and computer science with a focus on

service architecture and security (Otto et al., 2016;

Teuscher, 2018; Otto et al., 2019).

Against the background of human-computer inter-

action, this brings with it new roles and tasks and as-

sociated new user interfaces for users. For this reason,

potential users respective roles, as well as business

critical and high risk tasks connected with the sys-

tem, must be researched. In this respect, an error-free

performance must be enabled to ensure successful in-

teraction. The analysis focuses for instance on ac-

1

The title ”Industrial Data Space” has been replaced by

”International Data Space”. At the beginning of the project,

the focus was limited to industrial domains and expanded in

the course of the project.

tivities (What does the user do?), settings (How does

the user think about the system?) and skills (What is

the existing experience with the system?). In order to

merge and present the extensive and complex connec-

tions on the user level intuitively, high demands are

placed on the analysis. Topic-centred interviews with

experts from the domain were conducted to identify

business-critical, high-risk tasks and user needs. In

the subsequent analysis, the insights gained are de-

rived in user models and provided with, for example,

a name, a function, a usage context as well as tasks

and activities, transferred into personas. By provid-

ing personas, for instance, a development team can

put itself in the position of a potential user and thus

more easily understand its perspective during the de-

velopment process. Segmentation and cluster analysis

methods are used to develop primary and secondary

personas, which represent the user groups. Using a

hierarchical task analysis (HTA) in the analysis of so-

lution independent tasks, the goals, tasks and actions

of users are determined and structured (Diaper and

Stanton, 2003; Sharp et al., 2019). Summarizing, the

research work aims at the creation of generic require-

ments, which are based on a cross-domain task analy-

sis. In this context, the article addresses the following

research questions:

1. How can the users of the IDS be characterized?

2. What tasks do these users have perform?

These persons and their tasks are the basis for a user-

202

Werkmeister, T.

Personas and Tasks for International Data Space-based Ecosystems.

DOI: 10.5220/0010146902020209

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2020), pages 202-209

ISBN: 978-989-758-480-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

centered development of the user interface of IDS sys-

tems.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 International Data Space

The IDS represents a reference architecture model

2

based on a high level of abstraction (Otto et al., 2019).

Farther, the IDS is to be understood as a global virtual

data room, in which the participants are enabled to ex-

change and link data. The human-computer interac-

tion is technically established by the IDS-connectors

which connect data of machines, processes and sys-

tems and can be controlled by the participants via user

interfaces. This network

3

involves different partici-

pants in specific roles who interact with each other,

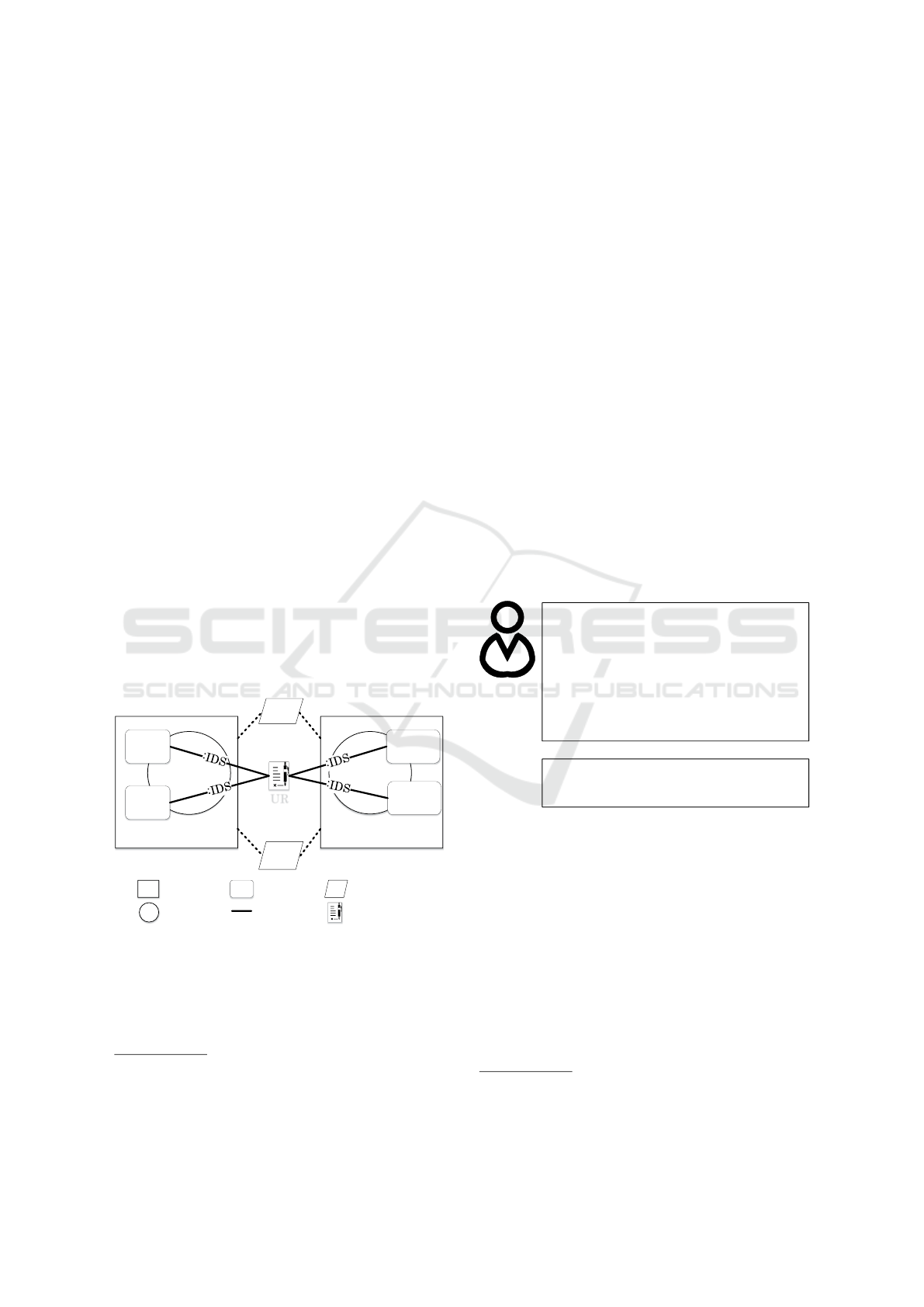

Figure 1 shows examples. The functions of the role

enable data to be integrated and controlled, data to be

made available for exchange, and data to be received

from the data provider. In the exemplary scenario, the

company (1) provides or exchanges data with the par-

ticipant/s in other companies (n) via a connector. The

associated data usage restrictions (UR) of the appli-

cation case regulate the contractual framework condi-

tions. The configuration and management of data ex-

change is controlled via user interfaces (UI). Broker

and Appstore are optional factors. There are currently

-Usage

restrictions

-IDS Connector

Company 1

Company n

UI

UI

-Essential role-Participants

UI

-User Interface

-Optional role

Broker

Data

Owner

Data

Provider

Data User

Data

Consumer

UR

App

Store

Figure 1: Roles and interactions in the Industrial Data

Space.

a few company-specific developments of connectors,

but there are no generally valid user interfaces that

allow cross-domain use. The IDS enables the partici-

pants to exchange controlled data. The establishment

2

This research topic will be examined from various per-

spectives in further scientific papers (Brost et al., 2018;

Graube, 2018).

3

also referred to as ”Business Ecosystem”

of contact can be made directly or via intermediaries.

If the data link is established, intervention by the par-

ticipants is optional. In this all-embracing scenario,

the human being as a participant is essential for es-

tablishing and controlling the connections. Each par-

ticipant has to take on different roles in which he has

to perform specific tasks. These participants or per-

sons and their tasks must be identified.

2.2 Analysis of Users

The persona originates from psychology and is de-

scribed as the outwardly shown attitude of a person.

In the field of psychology, the persona serves social

adaptation and is sometimes also identical with a self-

image (Jung, 2011). In the field of Human Com-

puter Interaction this procedure was transferred and

developed further by a multitude of authors

4

. A per-

sona is an abstractions of groups of real persons who

share common characteristics and needs. Further, per-

sonas are hypothetical stereotypes constructed from

the characteristics and behavior of real people, as fig-

ure 2 illustrates. A persona description is fictitious,

Position: skilled worker

Name: Felix Seidel

Age: 24 years

Marital status: single, no children

Company: MNI-Systems GmbH

Department: Production and

Manufacturing

Characteristics: motivated, precise,

tech-savvy

descriptive representations

quickly graspable knowledge

good usabiblity

"My

motto"

Personel

Expectations

Figure 2: Persona example.

but precise and specific in order to encourage the

empathy of the development team (Pruitt and Adlin,

2005; Pruitt and Adlin, 2006). By dropping redundant

or unessential information personas keep their stereo-

typical characters and become clearly distinguishable

from each other. When comparing the persona de-

velopment process according to Cooper (2015) and

Pruitt (2006) it should be noted that the basic process

at the beginning is similar in data collection, process-

ing and analysis. However, Cooper (2015) focuses

on the behavioral variables from the beginning. The

comparison is shown in the table 1.

4

(Pruitt and Adlin, 2005; Pruitt and Adlin, 2006; Mul-

der, 2006; Sears and Jacko, 2009; Mayas et al., 2012;

Cooper et al., 2015)

Personas and Tasks for International Data Space-based Ecosystems

203

Table 1: Identification variables and values and personas

Persona procedure models of Cooper (2015), Pruitt (2006).

Artifact Cooper Pruitt

Variables

and

values

Identify behavioral

variables, Map

interview subjects

to behavioral

variables.

Discuss categories

of users,

Process data.

Personas

Expand description

of attributes

and behaviors,

Designate persona

types.

Develop skeletons

into personas,

Validate the

personas.

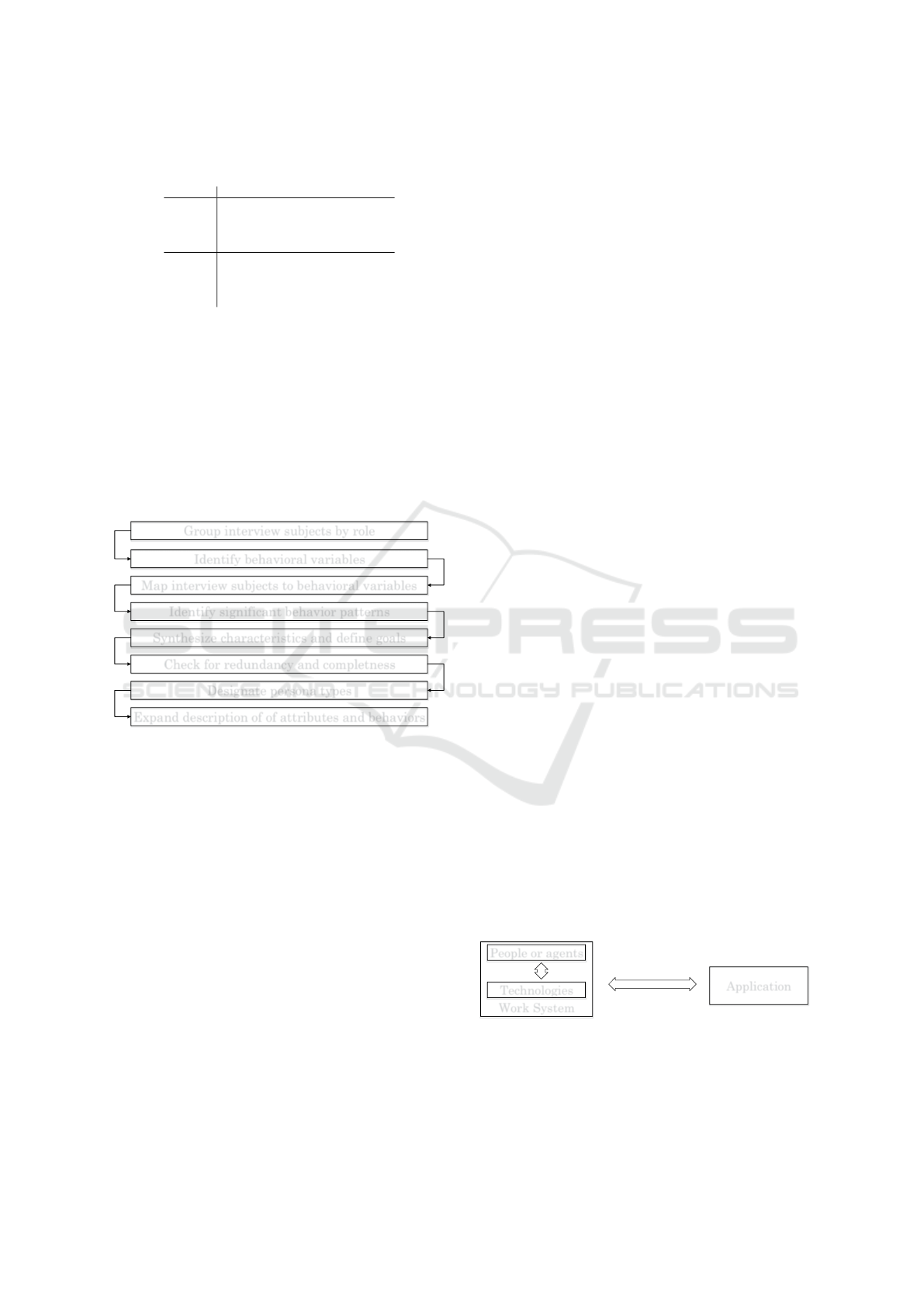

Referring to Cooper (2015) different roles are in-

terviewed, from which behavioral variables are to be

derived. Following this, the variables are assigned to

the interview partners and significant behavioral pat-

terns are identified. The individual components form

a new unit through their composition. After checking

for rendudance and completeness, the stereotypes can

be named. In the further course these are subject to

a constant expansion. The procedure is shown in the

figure 3.

Group interview subjects by role

Identify behavioral variables

Map interview subjects to behavioral variables

Identify significant behavior patterns

Synthesize characteristics and define goals

Check for redundancy and completness

Designate persona types

Expand description of of attributes and behaviors

Figure 3: Persona creation process according to Cooper

(2015).

According to Cooper (2015) and Mayas (2012)

personas can be understood as a ”design tool” used

early in the development process. They offer the fol-

lowing strengths (Mayas et al., 2012; Cooper et al.,

2015)

• User-centered determination of goals and tasks in

dealing with a system, product or service.

• Creation of a common communication system for

the development team and stakeholders involved.

• Mediation of a design consensus.

• An early evaluation of design decisions using per-

sonas instead of real users.

• Support of product marketing.

• Support the identification of actors and scenarios

in IDS.

• The prioritization of system requirements.

• Reflect the ideated tasks and activities of a role.

• In the requirements review or test phases, the use

of personas ensures that the user perspective is

taken into account and ensured.

• By integrating the user perspective Personas sup-

port in this case by decision making, evaluation or

even compliance with requirements.

• Additionally, the persona method closes the gap

between requirement-oriented, user-centered soft-

ware development and human-computer interac-

tion.

The approach according to Cooper (2015) is very

suitable for the present research project, as it se-

lects the observable characteristics of people and later

condenses these into personas. Furthermore, the re-

quirements elicitation and persona development pro-

vides the opportunity to derive context scenarios from

which interaction design principles and patterns can

be created.

2.3 Analysis of the Tasks

Task analysis is primarily concerned with the analy-

sis of processes (procedural knowledge). To be able

to analyze procedural knowledge, it is necessary that

a user has structured knowledge about the system and

the application domain. This is where mental models

are used for task analysis. These are formed by in-

teraction with a system, by observing the relationship

between one’s own actions and subsequent system re-

actions (Benyon, 2013). If the structured knowledge

is available, the analysis of the procedural knowledge

(user, system, application domain) can be performed.

The task analysis deals with the performance of a

”work system” which is related to the user and the

technology of a certain application domain. In the

figure 4 the relationship of the ”performance of work”

between the work system (consisting of the human –

people or agents and the technology) and the applica-

tion is visualized. A task is seen as a goal in combi-

nation with a certain amount of actions. The goals,

tasks and actions of the users are the focus of the con-

sideration (Benyon, 2013). The methods of task anal-

Work System

People or agents

Technologies

Application

Performace of

work

Figure 4: Task analysis according to Benyon (2013).

ysis can be divided into two superordinate categories.

On the one hand, there is the method of task logic, in

which the sequences of work steps that the work sys-

tem must go through to achieve a goal are defined. A

CHIRA 2020 - 4th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

204

typical example of task logic is hierarchical task anal-

ysis (HTA). On the other hand, there is the method

that deals with the understanding of cognitive aspects.

In this method, the cognitive processes that a user has

to go through in the work system in order to reach a

goal are analysed. A typical example for the analy-

sis of cognitive aspects is GOMS – Goals, Operators,

Methods, Selection Rules (Benyon, 2013). However,

this method is based on already existing interaction

solutions. The purpose of an HTA is to concretise

and fix the purpose of the analysis as far as possible.

Subsequently, the task objectives are to be defined.

Furthermore, the data for the preparation of the task

modelling shall be collected. In the following, a val-

idation is carried out, in which the tasks are broken

down and checked with, for example, a development

team or users. This identifies significant paths or ac-

tions. This step enables the development of possible

hypotheses about user performance, which are to be

tested. The figure shows an example for the program-

ming of a video recorder. In the sequence of tasks of

0. Record a TV

programme

1. Put tape

into VCR

2. Program

the TV

Channel

3. Program

the start and

end times

4. Set to

automatically

record

2.1 Press

channel up

2.2 channel

down

1.1 Find

suitable tape

1.2 Ensure

there is

enough tape

1.3 Insert

into VCR

Plan 0: 1-2-3-4-end

Plan 1: 1.1-1.2-1.3-end

Figure 5: HTA according to Benyon (2013), Basic example:

HTA for programming a video recorder.

the main task 0. Record a TV programme, the tasks

with subtasks, 1. Put tape into VCR, 2. Program the

TV Channel, etc. and actions 1.1 Find suitable tape

and 2.1 Press channel up illustrated in a hierarchy.

The HTA method is based on a graphical represen-

tation in one of the structure chart notation forms. In

addition, task sequences with subtasks and actions are

displayed in a hierarchy. This form of presentation

allows an overview of all tasks and also serves for

quick validation with involed persons. The method

focuses on the task objectives and discloses the user’s

task solution process. The user and his or her needs

are placed in the foreground. Furthermore, signifi-

cant paths or actions can be identified. HTA also al-

lows information to be given on whether an iteration

or selection of tasks is present. Structured paths in

the form of a ”plan” are possible via the hierarchy.

Due to the high novelty value of the system for the

present research question, both the personas and the

task analysis must be carried out with theme-centred

interviews.

2.4 Theme-centred Interviews

Theme-centred interviews are characterised by the

setting of relevance by guiding the interview partic-

ipants to a certain degree. The conduct of certain the-

matic areas is specified in the form of guiding ques-

tions. Furthermore, narrative generating questions

and structuring questions can be combined (Schorn,

2000; Witzel, 2000; Bohnsack et al., 2018). Simi-

lar to the expert interview, the criteria of restriction to

thematic complexes are set, which presupposes exist-

ing knowledge of the subject area. In the execution of

the interview the interviewer steers by means of open

questions. Here the narrative potential of the inter-

view partner within the given thematic complex is to

be exploited as much as possible. The procedure of-

fers the possibility to quickly identify initial insight in

a largely unknown field of knowledge. The extensive

information from the theme-centered interviews can

be evaluated with a qualitative content analysis.

2.5 Qualitative Content Analysis

Qualitative content analysis is a method of data eval-

uation. This method originates from empirical social

research, which aims to order and structure unam-

biguous and latent content (Mathes, 1992).

The method was applied in Human Computer In-

teraction and has been further developed by many re-

searchers

5

. Data material shall be evaluated induc-

tively, deductively or inductive-deductively. Inductive

coding – categories used are derived from the data

material. Deductive coding – categories are derived

from one or more theories. A mixed form of both

codings is possible.

The figure 6 shows - according to Mayring (2010)

- the applied method. The procedure begins with the

determination of units of analysis. In the second step,

the text is divided into individual text sections and re-

produced in your own words. The next step is a gener-

alization of a defined level of abstraction. Afterwards

a first reduction by selection and deletion of para-

phrases with the same meaning takes place, a second

reduction by bundling, construction as well as the in-

tegration of paraphrases takes place on a desired level

of abstraction. The combined category system is then

verified together with the source material. The proce-

dure according to Mayring (2010) enables the extrac-

tion of results by a successive abstraction. Further-

5

(Mayring, 2010; Gl

¨

aser and Laudel, 2010)

Personas and Tasks for International Data Space-based Ecosystems

205

1. Determination of the analysis units

2. Paraphrase of text passages

3. Determination of the desired level of abstraction

Generalization of the paraphrases below this level of abstraction

4. First reduction by selection, deletion of paraphrases with the

same meaning

5. Second reduction through bundling, construction, integration of

paraphrases at the desired level of abstraction

6. Collation of the new statements as a category system

7. Checkability of the summarizing category system on the source

material

Figure 6: Process model summarizing content analysis

(Mayring, 2010).

more, the procedure enables the categories that ap-

pear in the further course of the project to be assigned

to a theory. These can additionally form a theoretical

framework. The Mayering method allows a high de-

gree of transparency despite a high degree of subjec-

tive interpretation. Thus, the possibility of traceability

and verifiability of decisions is given by coding.

3 RESEARCH IDEA

3.1 Research Question

This paper examines potential users and their needs

towards a new and still widely unknown system (IDS)

to answer the research questions:

1. How can the users of the IDS be characterized?

2. What tasks do these users have perform?

In the exploration of potential users, the goals, tasks

and actions of cross-domains are in the focus of a

completely new system. This task-oriented approach

provides essential basic information that can later be

used to create user-centered interaction design pat-

terns for the IDS.

3.2 Research Method

The persona method according to Cooper was used

to characterize potential users of the IDS, because the

field of application has to be newly discovered. No

target groups have yet been defined, only behavioural

variables can be extracted from the analyses, from

which personas can then be defined. The personas and

their tasks were surveyed with a qualitative content

analysis of the structured theme-centred interviews.

The tasks were also described with an HTA to extract

the task logic. This is of particular relevance for the

design of subsequent interaction.

3.3 Research Design

Structured, theme-centred interviews were conducted

with 15 experts from different sectors and functions,

for example from the automotive industry or agricul-

ture. Decisive for the selection of the participants

were:

• previous knowledge of the IDS,

• domain-specific knowledge,

• competence of their roles,

• years of experience in a domain as well as

• representativeness for different domains.

The interviews were conducted over a 14-week period

from 03 April to 08 July 2020. A written document

was produced which served as a guideline. The first

part analyzed information about the experience and

use of business ecosystems and included questions

about the industry and function of the Interviewpart-

ner, the number of employees in the company it repre-

sents and the use of business ecosystems. In the sec-

ond part, information was asked for, which served to

derive personas. For example, questions were asked

about activities, attitudes and skills. In the interviews

a simple form was chosen for the formulation of the

questions and their suitability was tested in a pre-test.

If the participant agreed to the expert discussion, he or

she received a written cover letter and the document in

advance. In principle, the interviews were conducted

by telephone, were usually held in 30-45 minutes and

were transcribed. Afterwards, inductive data analysis

was applied in a schema-based processing to deter-

mine the procedural knowledge. In the course of the

analysis, categories were developed from codes, from

which theories were derived and assigned.

3.4 Research Results

Identification of Domains

From the collection of the identified domains a

structure could be derived in figure 7, which allows

a first assignment of the users. From all identified

domains, from automotive, to energy, to overarching

domains, there are similar corporate functions rang-

ing from production and logistics to data security

and legal issues. In addition, the table 2 contains

information, which provides insights into the sizes

of companies represented by the interviewees. It

can be deduced that the use of ecosystems is not

dependent on the size of a company. Experience with

ecosystems is usually limited to 2 to 5 years, which

confirms the low number of connected actors in an

ecosystem. Another conclusion is that usually CEOs

CHIRA 2020 - 4th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

206

D1 Automobile

D3 Trade

D2 Agriculture

CF 1 Production

CF 2 Logistics

CF 3 Security

CF 4 Law

UF 0 Information

technology / development

D4 Energy

D5 Health

D6 Metal

D7 Digital banking

D8 Cross

Corporate functions

Domains

Figure 7: Overview of identified corporate functions and

domains.

Table 2: Business insights, experience and roles and sug-

gested roles for business ecosystems.

Company size

1-49 50-999 5000+

Number of

employees

4 3 3

Years of

experience

no

state.

< 1 1-2 2-5 5-10 10-15 15-20 20-30 >30

Years worked

with business

ecosystems

5 0 0 6 2 0 0 1 0

Interacting

actors

no

state.

1 1-2 2-5 5-10 10-15 15-20 >20 >300

Actors do you

interact with

5 0 0 0 1 1 0 4 1

Position/

Role/Function

CEO

CIO

Lawyer

Head of

Education

Managing

Director

Head of

Dept.

Service &

App. Mgr.

Solution

Arch.

Project

Manager

Security

Consultant

Experts w

i

th a

specific

position/ role

3 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 1

S

pec

i

f

i

e

d

ro

l

es

for IDS users

Num

b

er o

f

suggestions

1 2 3 4 7

S

tr

a

te

g

i

s

t

Co

m

pl

i

a

nce

M

g

r

.

Knowle

dg

e

Eng.

D

a

ta

Ar

c

hi

te

c

t

D

a

ta

I

nte

g

r

a

to

r

S

ho

ppi

ng

Ma

c

hi

ne

Op

e

r

a

to

r

Pr

o

je

c

t Ma

na

g

e

r

D

a

ta

S

c

i

e

nti

s

ts

Te

c

hn

i

c

i

a

ns

Production

D

e

c

i

s

i

o

n m

a

k

e

r

s

D

a

ta

e

x

pe

r

t

D

a

ta

s

uppl

i

e

r

J

o

urna

l

i

s

t

Di

g

itisation ex

pe

rt

Te

c

hn

i

c

a

l

m

a

na

g

e

r

La

w

y

e

r

CE

O

Ce

r

tif

i

e

r

Buy

e

r

Co

ntr

o

l

l

e

r

Fo

r

w

a

r

de

r

Lo

g

i

s

tics

e

x

pe

r

ts

1000-4999

1

Ma

r

k

e

tin

g

Sal

e

s

D

a

ta

Ma

na

g

e

r

D

a

ta

Ana

l

y

s

t

Domain ex

pe

rt

S

e

c

uri

ty

Offi

c

e

r

Br

o

k

e

r

and heads of departments are familiar with the topic.

However, users could be identified who will take on

a systemically relevant role in the ecosystem.

Table 3: Behavioral variables for the IDS.

Main activities of the user Main capabilities of the user

Data- Knowledge of. . .

exchange Domain-specific

provide Business data and processes

brokering IDS ecosystem

monitor Consulting

analyze IT knowledge

control Certification

sharing Project management

communicate Understanding of...

retrieve Analytical

track Continuous knowledge enhancement

Expectations Main motivation of the user

Trust in the ecosystem

Execute successful business

processes and transactions

Promoting networking Full control over the data

Readiness for digitization

Data governance

Data protection/security

Usability/Intuitively/self-explanatory

Personalization for different roles

Individualization of the user interface

Identification of Behaviour Variables

The core tasks have been identified as high-risk, eco-

nomically critical activities, ranging from data ex-

change, monitoring to data control. As a result, a high

level of trust and data protection plays on an over-

riding role. The users have a high level of expertise,

combined with a strong analytical capability as well

as information technology and domain-specific skills.

Nevertheless, they attach great importance to

the greatest possible simplicity of the user interface,

which is intuitive to use. The identified behavior vari-

ables are shown in the table 3 and sorted by relevance.

Identification of Personas in IDS

The study revealed a number of 5 personas. These

are: Robert Becker – Data Economy Executive,

Virginia Williams – Engineer, David Holler – De-

partment manager, Dr. Paul Conner – Data Ana-

lyst/Scientists and Mike Chester – Developer. Three

personas are described as examples which show the

diversity of the tasks. The description of personas

consists of the following parts;

• name with additional term in the context of its be-

havioral variable,

• a persona illustration and a typical statement,

• the most representative requirements,

• overview of personal information,

• expectations of the IDS and

• description of a typical daily routine.

In the figure 8 a persona is introduced.

IDS Profile

Usage: Daily use of IDS in logistics.

System knowledge: medium

System use: 3 years

Interaction partners: approx. 12

It is important to him: secure data exchange, promote digitisation

Preferences: adherence to schedules, planning scope

Limitation: limited IT know-how

David Holler – The on-schedule logistics

specialist

is 43 years old and single.

lives in Dortmund.

David expects

Prompt information on the status of deliveries and outgoing deliveries

an easy handling of the system

a fast and efficient completion of tasks

no delays

Notes of daily work

#works daily with about 6 different participants under and overlapping

suppliers #must work in different systems – it is not easy and clear –

causes stress #must follow every process closely # would prefer to work in

one system only #has many years of experience with the IDS #has a lot of

confidence in the system #has worked in a project on the introduction of

the system #wants to have access to all information and tasks at a glance

#sees the IDS as the best way to access all information and tasks #wants

to work on his tasks without media and information breaks #no longer

wants to worry about late status reports of deliveries #needs real-time

data on his dashboard, advises new participants in IDS – very complex

"Especially small and medium sized companies want to use

IDS, but they do not want to think about what the system

actually does."

Figure 8: Persona David Holler The on-schedule logistics

specialist.

Personas and Tasks for International Data Space-based Ecosystems

207

Persona David Holler – Logistics specialist David

Holler is a 43-year-old single department manager of

an automotive supplier from Dortmund. He works

with the Business Ecosystem IDS and likes to save

himself the work with different systems. He is an

on-schedule IT-affine person who tries to complete

his tasks on time. Due to his regular use of the

system, David is very familiar with it, but lacks

in-depth background knowledge. His working day is

facilitated by trust in the system. Every now and then

he has to work with different systems, but he is able

to gain more and more participants who participate in

the digital processes of the company. David expects

timely information about the status of deliveries, easy

handling of the system to get the job done in the best

possible way and to avoid delays.

Persona Julian Massey – Domain and IT con-

sultant Julian (29 years) works as a consultant in a

company with over 5000 employees. In his 10 years

of experience he has developed analytical skills.

Julian also has good IT skills, has a good overview

of the departments due to his education and is also

good with people. Most recently, he participated in a

further training course on the topic of digitalization.

All this enables Julian to deal with processes, actions

and people related to it in his daily work. In his reg-

ular training sessions with his colleagues he imparts

knowledge about data exchange, data switching, data

control and monitoring. With the IDS, Julian sees a

great potential to bring his company to a good level

of maturity in digitization.

Persona Mike Chester – Developer and IT ex-

pert The developer and programmer Mike is 28 years

old and an innovative employee. For about 3 years

he has been working on industrial data and business

ecosystems. Two years ago the CEO decided that his

company should be IDS certified. For this, Mike had

to do a lot of bureaucratic and programming work.

After the certification, he developed interfaces which

established a connection between the machines of his

company and a supplier. Since then, Mike’s tasks

include the implementation of the requirements,

which are taken up by a domain and IT consultant.

For this, Mike develops front- and backend solutions.

This means that he needs to know the user needs and

he must have knowledge of interface programming.

Of course, there are always hurdles in development

and unfortunately there are not many forums where

he can share his knowledge and quickly absorb

new knowledge. Mike’s development work would

be made much easier by design templates, so he

wouldn’t have to start from scratch again and again.

Nevertheless, Mike is convinced that his CEO’s

decision was the right one and that data exchange via

business ecosystems is a forward-looking approach.

Identification of Tasks in IDS

Core activities were identified which are configurable,

manageable as well as processable, traceable and

traceable as information objects:

0 A

pp

Store/Mark

etp

lace 16 Lan

g

ua

g

e mana

g

ement

1 Participants 17 Development environment

2 Dashboard 18 IT Asset

3 R

ig

hts and role administration 19 Research and

development

4 Contracts 20 Mediate

5 Data securit

y

21 Connector

6 Data/data streams 22 Mana

g

ing

unit

7 Official documents 23 Digital twins (Machines)

8 L

eg

al rules 24 Communication

9 Business Rules 25 Collaboration

10 T

ransp

orts 26 Document

11 Verification 27 A

cquiring

application

12 Projekt Management 28 Operate machines

13 Mark

eting

29 Finance

14 Events 30 Environmental Mana

g

ement

15 Tasks 31

Q

ua

lity as

surance s

y

stem

Figure 9: Identified core tasks.

The table 9 shows an consolidation example of the

major task Manage contracts (Plan 4: 1-2-3-4-end)

for the management of the contracts and its subtasks

(1. Create a new contract, 2. Edit existing contract, 3.

Show all contracts).

0. Manage contracts

1. Create a new

contract

2. Edit existing

contract

3. Show all contracts

4.3.2 Show all

expired contracts

4.2.1 Show

contract partner

4.2.2 Edit

contract partner

4.1.1 Show contract

partner

4.1.2 Choose

contract partner

4.1.3 Show template

contracts

(Plan 4: 1-2-3-4-end)

(Plan 4.1:1.1-1.2-1.3-end)

4.2.3 Delete

contract partner

(Plan 4.2:2.1-2.2-2.3-end)

4.3.1 Show all

current contracts

(Plan 4.3:3.1-3.2-end)

Figure 10: Hierarchical task analysis – Manage contracts.

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

The proposed combination of methods presents in

its entirety an approach for identifying personas and

tasks of a new domain. The basic variables, per-

sonas and tasks related to the IDS are to be confirmed

in this empirical study, so far an exemplary set of

five personas and 31 core tasks could be identified.

The application of the methods promotes the intro-

duction of a human-centric design in the domain of

business ecosystems. Personas intensify the differ-

entiated consideration of the widespread target group

and the translation of user needs into concrete tasks.

CHIRA 2020 - 4th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

208

In this highly specialized field of knowledge, hardly

any knowledge about the users is known, so that cur-

rently information technicians or scientists are in-

volved. The persona method, however, is mostly used

to identify familiar people in everyday life, so it is

difficult to imagine in the context of the IDS. The

IDS is subject to constant development. The knowl-

edge gained about the users is also subject to constant

further development due to this fact, but represents a

first human-centred approach. The personas can also

be represented in different business areas and compa-

nies in various forms. Going forward, the identified

tasks have a generic approach. Both can be modified

in the future. However, the tasks and processes have

to be reviewed again and again, as they are subject to

constant change. Taking these points into account, it

should be noted that the personas and tasks confirmed

in this study are not exhaustive and are being further

developed and modified in the scientific debate, they

represent a first approach. The described personas and

tasks are a framework for the overall design of util-

ity and usability in all phases of development. Inter-

action patterns can be derived from the tasks, which

can be tailored exactly to the needs of the personas.

For further developments they also have the function

to provide a framework of orientation within which

the requirements for interaction with the International

Data Space can be detailed.

REFERENCES

Benyon, D. (2013). Designing Interactive Systems: A Com-

prehensive Guide to Hci, Ux & Interaction Design.

Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, London, New

York, a. o., 3 edition. pp.32-251.

Bohnsack, R., Meuser, M., and Geimer, A. (2018). Haupt-

begriffe Qualitativer Sozialforschung. UTB GmbH.

Brost, G., Huber, M., Weiß, M., Protsenko, M., Sch

¨

utte, J.,

and Wessel, S. (2018). An ecosystem and iot device

architecture for building trust in the industrial data

space. Cyber-Physical System Security Workshop.

Cooper, A., Reimann, R., Cronin, D., and Noessel, C.

(2015). About Face: The Essentials of Interaction De-

sign. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Indianapolis, 4 edition.

p. 61.

Diaper, D. and Stanton, N. (2003). The Handbook of

Task Analysis for Human-Computer Interaction. CRC

Press.

European Commission, Directorate-General of Com-

munications Networks, C. . T. (2013). Ten-

der specifications-european data market-smart

2013/0063. Retrieved on May 23, 2019.

Gl

¨

aser, J. and Laudel, G. (2010). Experteninterviews und

Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Lehrbuch - VS Verlag

f

¨

ur Sozialwissenschaften. VS Verlag f

¨

ur Sozialwis-

senschaften.

Graube, M. (2018). Linked enterprise data as semantic and

integrated information space for industrial data. Mas-

ter’s thesis, Technische Universit

¨

at Dresden.

Jung, C. G. (2011). Psychologische Typen. Patmos Verlag,

3 edition.

Mathes, R. (1992). Hermeneutisch-klassifikatorische

inhaltsanalyse von leitfadengespr

¨

achen:

¨

uber das

verh

¨

altnis von quantitativen und qualitativen ver-

fahren der textanalyse und die m

¨

oglichkeit ihrer kom-

bination. In Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J. H. P., editor, Anal-

yse verbaler Daten :

¨

uber den Umgang mit qual-

itativen Daten, ZUMA-Publikationen. Westdt. Verl.,

Opladen. Retrieved on May 6, 2020, pp. 402-424.

Mayas, C., H

¨

orold, S., and Kr

¨

omker, H. (2012). Meet-

ing the challenges of individual passenger information

with personas. Retrieved on June 3, 2020.

Mayring, P. (2010). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundla-

gen und Techniken. Beltz P

¨

adagogik. Beltz, Weinheim

and Basel, 12 edition. p. 70.

Mulder, S. (2006). User Is Always Right, The: A Practical

Guide to Creating and Using Personas for the Web.

New Riders.

Otto, B., Auer, S., Cirullies, J., J

¨

urjens, J., Menz,

N., Schon, J., and Wenzel, S. (2016). Indus-

trial Data Space - Digitale Souver

¨

anit

¨

at

¨

uber Daten.

Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft zur F

¨

orderung der ange-

wandten Forschung e.V., Industrial Data Space e.V,

M

¨

unchen. Retrieved on March 15, 2017, pp. 4-35.

Otto, B., Steinbuß, S., Teuscher, A., and Lohmann, S.

(2019). Reference Architecture Model. International

Data Spaces Association, Berlin, 3 edition. Retrieved

on April 08, 2019, p. 61.

Pruitt, J. S. and Adlin, T. (2005). The Persona Lifecycle: A

Field Guide for Interaction Designers. Keeping Peo-

ple in Mind Throughout Product Design.

Pruitt, J. S. and Adlin, T. (2006). The Persona Lifecycle-

Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design.

Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 500 Sansome Street,

Suite 400, San Francisco, CA 94111.

Schorn, A. (2000). Das themenzentrierte interview. ein ver-

fahren zur entschl

¨

usselung manifester und latenter as-

pekte subjektiver wirklichkeit. Forum: Qualitative

Sozialforschung, 1(2). Retrieved on May 15, 2020.

Sears, A. and Jacko, J. (2009). Human-Computer Interac-

tion: Development Process. Human Factors and Er-

gonomics. CRC Press.

Sharp, H., Preece, J., and Rogers, Y. (2019). Interaction

Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction. Wi-

ley.

Teuscher, A. (2018). Industrial Data Space Association -

Souver

¨

anit

¨

at

¨

uber Daten, volume 3. Fraunhofer Insti-

tut. Retrieved on May 17, 2019.

Witzel, A. (2000). The problem-centered interview. Forum

Qualitative Sozialforschung, 1(1). Retrieved on May

15, 2020.

Personas and Tasks for International Data Space-based Ecosystems

209