Immersive Technologies in Retail:

Practices of Augmented and Virtual Reality

Costas Boletsis

a

and Amela Karahasanovic

b

SINTEF Digital, Forskningsveien 1, 0373 Oslo, Norway

Keywords:

Augmented Reality, Customer Engagement, Retail, Shopping, Virtual Reality.

Abstract:

In this work, we examine the value that immersive technologies can bring to retailing through the retail prac-

tices they facilitate. To that end, a literature review is conducted resulting in the documentation of 28 aug-

mented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) applications from 38 publications. After analyzing the applica-

tions’ functionality and use in retail, the following AR/VR-enabled retail practices emerged: branding and

marketing; sales channel; after-sale customer service; virtual try-on; customer-as-designer; virtual training;

and workflow management. A principal observation from the analysis is that current AR/VR applications

are used mainly for customer-related innovation, with “branding and marketing” being a dominant practice.

Simultaneously, some practices are available to serve organization-related and support-related innovation. Fi-

nally, it was observed that AR is a popular technology in the retail environment and of high practical value,

being an ideal fit for the purchase journey and workflow management. However, VR is more difficult to im-

plement in retail, as it can be more expensive and complicated to integrate with the sales channel. However,

it can create strong emotional engagement due to high immersion and act as a useful tool for branding and

training. Therefore, these two technologies in retail and their strengths can supplement each other, thereby

creating promising innovation strategies when combined.

1 INTRODUCTION

Immersive technologies, such as augmented reality

(AR) and virtual reality (VR), are increasingly used

in retail environments (Bonetti et al., 2018; Javornik,

2016; McCormick et al., 2014; Caboni and Hagberg,

2019). VR enables the creation of fully immersive

virtual environments that “replace” reality (Steuer,

1992; Boletsis and Karahasanovic, 2018) Recently,

major changes in VR systems have taken place, re-

viving the interest in the technology. VR has be-

come accessible, up-to-date, and relevant again due

to the low acquisition cost of VR hardware and the

rapid increase in virtual environments’ quality (Ol-

szewski et al., 2016; Boletsis, 2017; Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018). On the other hand, AR is

closer to reality because its technical characteristics

enable the augmentation of the real environment (Mil-

gram and Kishino, 1994; Azuma, 1997). Advances in

the smartphone industry have allowed for the tech-

nology to become widely accessible, enabling users

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2741-8127

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3442-0866

to enjoy memorable AR simply through their smart-

phones’ screens (Billinghurst et al., 2015; Boletsis

and Karahasanovic, 2018). To fully exploit immer-

sive technologies’ potential in retail, one needs to un-

derstand the critical retailing areas in which their in-

novations can change the game (Grewal et al., 2018;

Boletsis and Karahasanovic, 2018).

The application of AR and VR in retailing has

been the subject of previous research. Caboni and

Hagberg (2019) formulated the various types of AR

applications in retail: online web-based applications;

in-store applications; and mobile applications. More-

over, the authors described the utilized methodology

for conducting a literature review of business-oriented

research around the use of AR in retail. Bonetti et al.

(2018) synthesized current debates to provide an up-

to-date perspective, incorporating issues relating to

motives, applications, and implementation of AR and

VR by retailers, as well as consumer acceptance. Fur-

thermore, in our previous work (Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018), we documented several AR/VR ap-

plications used in retail through a scoping review,

and we adopted an innovation-centric approach, ex-

amining the generic types of innovation that they tar-

Boletsis, C. and Karahasanovic, A.

Immersive Technologies in Retail: Practices of Augmented and Virtual Reality.

DOI: 10.5220/0010181702810290

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2020), pages 281-290

ISBN: 978-989-758-480-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

281

get, based on the “Ten Types of Innovation” business

framework by Keeley et al. (2013).

In this work, we take inspiration from the afore-

mentioned studies, in order to move to a subfield

that has not been covered yet, i.e., examining the

value that immersive technologies can bring to retail-

ing through the retail practices they facilitate. To that

end, this work contributes to the field of knowledge

by: i) documenting AR and VR applications for re-

tail, based on related research, ii) synthesizing the re-

tail practices that AR/VR applications address, iii) in-

vestigating the differences between AR and VR when

applied in the retailing domain, and iv) briefly dis-

cussing the innovation types that the AR/VR-enabled

retail practices serve.

The present study’s methodology follows a linear

approach and it is based on a literature review to in-

vestigate the use of AR and VR in retail. The lit-

erature review’s search elements, initially proposed

by Caboni and Hagberg (2019), have been used suc-

cessfully to document business-oriented research ear-

lier (Boletsis and Karahasanovic, 2018). Therefore,

we used and further extended these methodological

elements here. Whereas our previous study (Bolet-

sis and Karahasanovic, 2018) investigated AR/VR in

retail from an innovation-centric perspective, this re-

search takes a technology-centric perspective, focus-

ing on the retail practices that AR and VR technolo-

gies facilitate and the value and functionalities they

can support. Naturally, our previous (Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018) and current works supplement

each other, providing a more complete understanding

and overview of the topic from two different perspec-

tives. We aspire for this work to act as a guide for

researchers, developers, and practitioners in retail to

base their future decisions and designs around AR and

VR on existing theoretical and practical knowledge.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2

presents the study’s methodology. Section 3 describes

the literature review process that was followed to doc-

ument the AR and VR applications. Section 4 theoret-

ically analyzes the literature review’s results, focusing

on the addressed retail practices. Section 5 discusses

the results, focusing on the AR and VR technologies,

with the paper concluding in Section 6.

2 METHODOLOGY

This study’s methodology is enabling the transition

from specific practice to general theory by following

a bottom-up approach. The ultimate goal is to investi-

gate the use of AR and VR in retail through the analy-

sis of commercial AR and VR retail applications that

appear in the literature. At first, we document cur-

rent AR/VR-enabled retail practices through a litera-

ture review and axial coding. Then, we analyze these

practices and the characteristics of and differences be-

tween AR and VR in retail are discussed.

The reasoning behind the implemented methodol-

ogy is to examine current practices, as documented

and accredited by peer-reviewed literature; then for-

mulate related theory out of these practices, so that

future research and practice of AR/VR in retail can

have a better overview of the field and the necessary

theory to ground/analyze future contributions.

3 LITERATURE REVIEW

Certain methodological elements from the our previ-

ous preliminary literature review (Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018) were also implemented and are

highlighted below. Despite being a scoping litera-

ture review, the guidelines for systematic literature

reviews (Kitchenham, 2004; Beecham et al., 2008)

were considered while constructing the review pro-

cess and its stages, to ensure a seamless expansion of

this scoping literature review into a systematic one in

the future, as described in Section 6.

3.1 Search Strategy

A literature search was performed in the Scopus aca-

demic search engine during December 2019 and May

2020. The Scopus search engine searches through the

databases of other publishers, such as ACM, Elsevier,

IEEE, Springer, Sage, Oxford University Press, Cam-

bridge University Press and many more. The key-

words used for the retrieval of eligible articles were

“augmented reality application” or “virtual reality ap-

plication” and “retail”. No publication-year-related

filtering was used. Eligible articles were also iden-

tified through backward reference searching, i.e., by

screening the retrieved publications’ reference lists

(Vom Brocke et al., 2009). Scopus, Google Scholar,

Google Search, and Web of Science were utilized

for the backward reference searching to run general

searches of specific references and to identify relevant

articles.

3.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

At this point, the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the

preliminary literature review (Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018) were used. Therefore, peer-

reviewed articles with the following characteristics

were included:

WUDESHI-DR 2020 - Special Session on User Decision Support and Human Interaction in Digital Retail

282

1. written in English and accepted and presented in

peer-reviewed publications,

2. presenting, describing, or analyzing – at any ex-

tent – a commercial AR or VR retail application,

which is used by retail businesses in real life (e.g.,

being an application in an app-store, application

or service in a physical store, et al.).

Based on inclusion criterion #2, research prototypes

and conceptual descriptions of applications were ex-

cluded.

The criteria’s formulation is based on the facts

that: i) the peer-review process adds to the credibil-

ity and reliability of the publications and the respec-

tive presented applications, and ii) the actual use of

the VR and AR applications by retail businesses en-

sures that the presented applications are existing, us-

able, and beyond the conceptual level (Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018).

3.3 Screening Process and Results

The initial search elicited 243 articles. In total, 96

articles were identified as appropriate for inclusion

while 25 articles satisfied the inclusion criteria. Then,

backward reference searching of the extracted arti-

cles’ references took place, resulting in 13 additional

articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The au-

thors reviewed all 38 articles independently. The cat-

egories and themes of the review were shaped by the

authors/reviewers, based on the data extraction pro-

cess. A high level of agreement (>80%) between

the authors/reviewers was achieved, regarding the in-

clusion/exclusion decisions and the formulated cat-

egories and themes. Any disagreements were dis-

cussed and settled.

3.4 Data Extraction & Synthesis

The data extracted from each article included: the ar-

ticle’s full reference and additional descriptive infor-

mation regarding the AR/VR application, such as the

title, description, and/or use details.

The two reviewers jointly performed the data ex-

traction process. The descriptions of the AR/VR ap-

plications in retail were based on the descriptions

provided in the articles and/or other related publica-

tions. For demonstration purposes, YouTube video

links with the applications’ functionality were also

collected by querying the title of each application on

YouTube.

The themes of the review were conjointly synthe-

sized by the two authors, based on the data extraction

process. The AR/VR applications’ retail practices

were formulated based on the applications’ descrip-

tions and functionality, as presented in the reviewed

articles and the video demonstrations. Axial coding

of the documented AR/VR practices took place so

that each theme contains comparable and consistent

categories. The main themes identified in the review

and tabulated (Table 1) were:

• the AR/VR retail applications,

• their features, i.e., description, utilized technol-

ogy, and video demonstration, and

• the AR/VR applications’ retail practices.

4 RESULTS

4.1 AR/VR-enabled Retail Practices

The literature review resulted in the analysis of 28 AR

and VR applications (AR/VR: 19/9). After document-

ing and analyzing their functionality and use in retail,

the following retail practices emerged:

• Branding and Marketing: Even though these

terms are quite different from their scope, in this

case, they are operating together. AR/VR applica-

tions can be used i) in a short-term, tactical way

to engage/activate customers by fostering com-

pelling, emotional interactions and, at the same

time, ii) in a long-term, strategic way to estab-

lish a brand as technologically innovative and cre-

ative. Most of the times, the “marketing” use

of AR/VR has omnichannel functionality (e.g.,

L’Oreal Makeup Genius, Tesco Discover, IKEA

VR Experience, McDonald’s Track My Maccas,

etc.), containing connections to other marketing

channels, such as magazines, social media, ad

videos, websites, and physical stores to create

strong brand experiences and innovative multi-

platform offerings (Verhoef et al., 2015; Boletsis

and Karahasanovic, 2018).

• Sales Channel: AR/VR applications can provide

an easy way to bring products or services to mar-

ket so that they can be purchased by consumers,

targeting to make immediate use of the cus-

tomer engagement that AR and VR can achieve

at a pre-sale level, e.g., during virtual try-ons,

customer-as-a-designer schemes, or various mar-

keting practices (Loureiro et al., 2019; Boletsis

and Karahasanovic, 2018). Therefore, they can

serve as sales channels, integrated into customers’

purchase journey through instant actions to buy

(e.g., Sephora Virtual Artist, IKEA Virtual Real-

ity Store).

Immersive Technologies in Retail: Practices of Augmented and Virtual Reality

283

Table 1: The reviewed AR and VR applications in retail.

Application Title Tech Description Demonstration Retail Practice References

Alibaba Buy+ VR VR application that allows customers to

browse and shop items in a virtual mall.

https://youtu.be/-HcKRBKlilg Sales channel

Branding & marketing

(Jean, 2017; Mustafa et al.,

2018; Farah et al., 2019; Bolet-

sis and Karahasanovic, 2018)

Audi Quattro Coaster AR Mobile application for building a 3D track

and displaying a 3D interactive model of a

car.

https://youtu.be/ZzQBAZ-2i24 Branding & marketing (Boletsis and Karahasanovic,

2018)

Auto Bild AR AR AR application for the Auto Bild magazine

that displays 3D objects and scenes when

certain parts of the magazine are scanned.

https://youtu.be/XQY leU6 5Y After-sale customer service

Branding & marketing

(Rese et al., 2017)

Carrefour VR VR VR application which takes users for a

roller-coaster ride while showcasing sev-

eral products.

https://youtu.be/513whiHw l0 Branding & marketing (Loureiro et al., 2019)

DHL Vision Picking AR Application for AR glasses to facilitate or-

der processing, warehouse planning, and

training of warehouse staff.

https://youtu.be/I8vYrAUb0BQ Workflow management

Virtual training

Branding & marketing

(Satoglu et al., 2018; Guo et al.,

2015; Miraldes et al., 2015; Bo-

letsis and Karahasanovic, 2018)

Dulux Visualiser AR Mobile application that allows users to test

paint colors on their walls using AR and a

mobile device’s camera.

https://youtu.be/4lMFxJ4PDXY Virtual try-on

Branding & marketing

(Scholz and Smith, 2016; Bolet-

sis and Karahasanovic, 2018)

Hyundai Virtual Guide AR Mobile application that serves as a car

owner’s manual.

https://youtu.be/qOMvl6-cP7o After-sale customer service

Branding & marketing

(Poushneh, 2018; Hilken et al.,

2018; Avila and Bailey, 2016;

Boletsis and Karahasanovic,

2018)

IKEA Catalog AR Mobile application that allows users to

scan select pages and images from the

printed catalog to access extended AR con-

tent and display it on top of real space.

https://youtu.be/uaxtLru4-Vw Virtual try-on

Branding & marketing

(Baier et al., 2015; Rese

et al., 2014; Rese et al., 2017;

Dacko, 2017; Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018)

IKEA Virtual Reality

Store

VR VR application for users to furnish a vir-

tual room in real scale and then get a list of

all items selected with the unique reference

code and price list.

https://youtu.be/6Uqpije1-TQ Sales channel

Branding & marketing

(Loureiro et al., 2019; De Silva

et al., 2019)

IKEA VR Experience VR VR application for users to experience and

customize a VR IKEA kitchen.

https://youtu.be/c-NUbGtAeYU Virtual try-on

Branding & marketing

(Man and Qun, 2017; Edvards-

son and Enquist, 2011; Kemke

et al., 2006; Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018)

L’Oreal Makeup Genius AR Mobile application that allows users to in-

stantly try on different styles of make-up.

https://youtu.be/zbBJfrkZRDI Virtual try-on

Branding & marketing

(Hilken et al., 2017; Hilken

et al., 2018; Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018)

Lego AR Studio AR Mobile application that creates a virtual

Lego gameplay experience to be combined

with physical Legos.

https://youtu.be/cHvcD2FrKew Customer-as-a-designer

After-sale customer service

Branding & marketing

(Moorhouse et al., 2018; Iyadu-

rai and Subramanian, 2016; Bo-

letsis and Karahasanovic, 2018)

WUDESHI-DR 2020 - Special Session on User Decision Support and Human Interaction in Digital Retail

284

Table 1: The reviewed AR and VR applications in retail (cont.).

Lego Connect AR AR application for the Lego catalogue that

displays 3D objects and scenes when cer-

tain parts of the magazine are scanned.

https://youtu.be/O-62MTcpcJE Sales channel

Branding & marketing

(Miraldes et al., 2015)

Lego Digital Box AR AR application that scans the surface of a

Lego box and presents a 3D object of its

content.

https://youtu.be/BUDIduApeLI After-sale customer service

Branding & marketing

(Miraldes et al., 2015)

McDonald’s Track my

Maccas

AR Mobile application for displaying 3D in-

teractive stories about a meal’s ingredients

and where the ingredients came from.

https://youtu.be/7iFQQGADjf4 After-sale customer service

Branding & marketing

(Gryb

´

s, 2014; Bresciani and

Ewing, 2015; Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018)

Mister Spex

Virtual Mirror

AR AR application for users to try on various

pair of glasses.

https://youtu.be/IPc07J5IH0I Virtual try-on

Sales channel

Branding & marketing

(Rese et al., 2017; Hilken et al.,

2017)

Mitsubishi Electric

MeView

AR AR application that serves as a virtual as-

sistant displaying instructions through 3D

models.

https://youtu.be/Edi02M1nS8g After-sale customer service

Branding & marketing

(Miraldes et al., 2015)

NikeID In-store AR VR AR projection of customized shoe designs

on top of real shoes.

https://youtu.be/5LNIXKXaCBE Customer-as-a-designer

Branding & marketing

(Bonetti and Perry, 2017; Bolet-

sis and Karahasanovic, 2018)

North Face

VR Experience

VR 360-degree film about traveling experi-

ences.

https://youtu.be/Cr-9ujLco50 Branding & marketing (Dulabh et al., 2018; Boletsis

and Karahasanovic, 2018)

RayBan Virtual Mirror AR AR application for users to try on various

pair of glasses.

https://youtu.be/2onjpEOQm64 Virtual try-on

Sales channel

Branding & marketing

(Rese et al., 2017)

Sephora Virtual Artist AR Mobile application that allows users to in-

stantly try on thousands of lip colors.

https://youtu.be/NFApcSocFDM Virtual try-on

Sales channel

Branding & marketing

(Mocanu, 2012; Yim et al.,

2017; Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018)

Tesco Discover AR Application for scanning Tesco publica-

tions to reveal additional content and pur-

chasing products using buy links.

https://youtu.be/gR7FsWaP3Mw Sales channel

Branding & marketing

(Bodhani, 2013; Baier et al.,

2015; Rese et al., 2014; Bolet-

sis and Karahasanovic, 2018)

Tesco Pele VR VR application for users to experience the

environment of a Tesco store and a football

field.

https://youtu.be/VXWhR k1vvc Branding & marketing (Loureiro et al., 2019)

Toms Virtual Giving

Trip

VR 360-degree film about a charity mission. https://youtu.be/jz5vQs9iXCs Branding & marketing (Grewal et al., 2018; Boletsis

and Karahasanovic, 2018)

Uniqlo’s Magic Mirror AR AR application for users to try on various

clothes in front of an AR mirror.

https://youtu.be/oUD57MpHAE8 Virtual try-on

Sales channel

Branding & marketing

(Balaji et al., 2018; Zhao and

Balagu

´

e, 2017; Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018)

Volkswagen Virtual

Golf Cabriolet

AR Mobile application for displaying a 3D in-

teractive model of a car.

https://youtu.be/pFS6EHzBGVc Branding & marketing (Bodhani, 2013; Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018)

Volvo XC90 Test Drive VR 360-degree experience about driving a car. https://youtu.be/HEkGRUkqjTA Virtual try-on

Branding & marketing

(De Gauquier et al., 2019; Bo-

letsis and Karahasanovic, 2018)

Walmart VR

in Academies

VR VR application for training employees. https://youtu.be/oRbmLBWdEoI Virtual training

Branding & marketing

(Carruth, 2017; Babu et al.,

2017; De Keyser et al., 2019;

Boletsis and Karahasanovic,

2018)

Immersive Technologies in Retail: Practices of Augmented and Virtual Reality

285

• After-sale Customer Service: The fact that im-

mersive technologies can blend with reality pro-

vides the opportunity for immersive applications

to add virtual content to real-life use contexts and

offer additional customer value. AR/VR appli-

cations can provide various after-sale services by

offering complimentary product-related informa-

tion in use-context (Gryb

´

s, 2014; Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018). This enables customers to

have their purchased products extended with new,

virtual content for several purposes (e.g., enter-

tainment content for Lego AR Studio, good pub-

licity content for McDonald’s Track my Maccas)

or to get useful after-sale customer support and

guidance (e.g., Hyundai Virtual Guide).

• Virtual Try-on: AR and VR can visualize “what

could be”. Virtual try-ons (VTOs) visualize the

use of certain products as 3D graphics in AR or

VR space. These try-ons enable the customers to

get an idea about how the product would work

or fit them, at a pre-sale stage, thus attempting

to affect purchase decision (Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018; Scholz and Smith, 2016; Hilken

et al., 2017; Hilken et al., 2018). The analy-

sis indicates a high concentration of VTOs ap-

plications. Customers can virtually try furniture,

clothes, and makeup products and more, as AR

3D models augmenting themselves and the phys-

ical space (e.g., IKEA Catalog, Uniqlo’s Magic

Mirror, Sephora Virtual Artist). VR VTOs im-

merse customers into VR spaces and try to com-

municate a sense of actually using the product

(e.g., IKEA VR Experience, Volvo XC90 Test

Drive).

• Customer-as-Designer: AR/VR applications can

be used to extend products’ value by involving

customers in the value-creation process. A com-

pany provides the AR/VR tools, and customers

can design the final product or formulate a dif-

ferent user experience with the product (Bolet-

sis and Karahasanovic, 2018; Moorhouse et al.,

2018). The “customer-as-designer” use can be

present at the pre-sale (e.g., NikeID In-store AR)

and/or after-sale (e.g., Lego AR Studio) stages.

• Virtual Training: AR/VR technologies can facil-

itate the development of virtual environments and

simulated scenarios, offering users high immer-

sion and engagement levels (Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018; Carruth, 2017; Babu et al.,

2017). Companies use these features for em-

ployee training in virtual settings (e.g., Walmart

VR in Academies).

• Workflow Management: AR/VR applications

can practically affect the backstage way that retail

works and utilize the technologies to provide bet-

ter workflow management, e.g., regarding ware-

house planning and order picking (DHL Vision

Picking). The extra layers of information that

can be visualized through these technologies – in

real or virtual environments – provide several op-

portunities to annotate and organize retail work-

flow further (Boletsis and Karahasanovic, 2018;

Satoglu et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2015).

4.2 Frequency of AR/VR-enabled Retail

Practices

The AR/VR applications’ analysis produced 56 in-

stances of the seven AR/VR-enabled retail practices

mentioned above (i.e., an average of two retail prac-

tices per application, one always being “branding

and marketing”). The AR applications covered 42

instances of retail practices, while VR applications

addressed 14 instances. The overall instances of

AR/VR-enabled retail practices per technology are

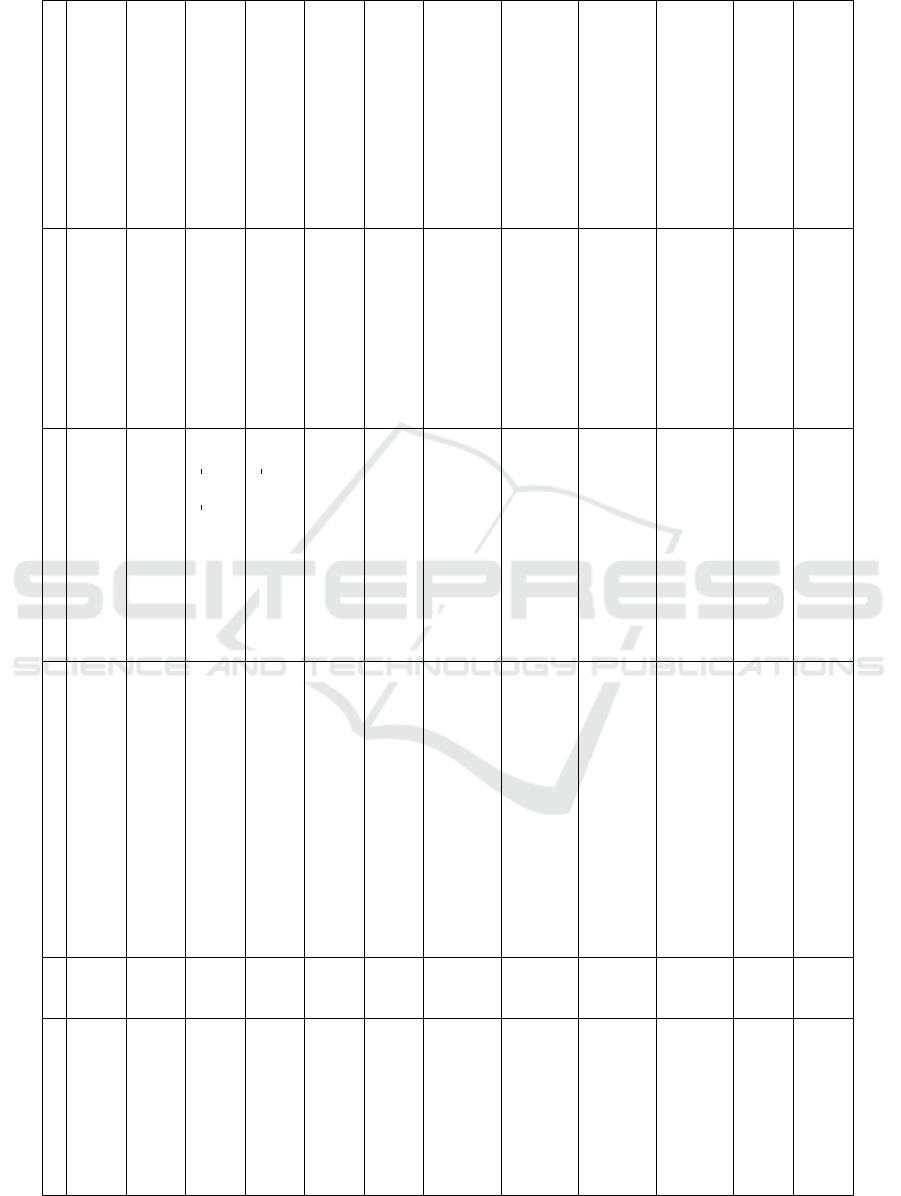

presented in Figure 1.

5 DISCUSSION

In this section, we examine and discuss the follow-

ing issues: i) what types of innovation in retail do the

documented AR/VR-enabled practices address (Sec-

tion 5.1); ii) how do the features of AR and VR in

retail compare (Section 5.2); and iii) what are the lim-

itations of this study (Section 5.3).

5.1 AR/VR-enabled Retail Practices &

Innovation

A main observation from Figure 1 is that current

AR/VR applications are used mainly for customer-

related innovation

1

. Branding and marketing is a

dominant practice, with all reviewed applications ad-

dressing it, along with potentially some additional

functionality (e.g., after-sale support service, virtual

try-on, et al.). Companies advertise their AR/VR

practices as an innovative feature and utilize the tech-

nologies to establish their brands and send the mes-

sage that they stand for innovation, exploration, and

creativity, thereby attempting to create loyal cus-

tomers (Boletsis and Karahasanovic, 2018). The

1

They are front-line innovations, including new product

lines, product categories, retail services, store formats or

channels to market (Hristov and Reynolds, 2015).

WUDESHI-DR 2020 - Special Session on User Decision Support and Human Interaction in Digital Retail

286

Figure 1: The number of instances of the AR/VR-enabled retail practices from the 28 reviewed AR/VR applications.

other retail practices that occupy that space con-

cern the use of AR/VR applications to provide added

customer value at different periods of the purchase

journey (Bonetti and Perry, 2017; Bonetti et al.,

2018): pre-sale (e.g., virtual try-ons, customer-as-a-

designer); sale (e.g., sales channel); and after-sale

(e.g., after-sale customer service).

At the same time, there is a limited number

of practices for organization-related

2

and support-

related innovation

3

processes, i.e., the virtual training

and workflow management retail practices. To tackle

this issue, the retail industry could apply AR/VR

innovation more intensively in support-related and

organizational-related processes. These innovations

could focus on organizing company assets – hard, hu-

man, or intangible – in unique ways that create value

and/or develop activities and operations that produce

a company’s primary offerings beyond the “business

as usual” stage. (Boletsis and Karahasanovic, 2018;

Keeley et al., 2013).

5.2 AR vs. VR in Retail

Apart from AR and VR retail practices, and the inno-

vation types they serve, we consider it useful to exam-

2

It mostly concerns business model innovation, which

might include new organizational structures, operating rou-

tines, or administrative processes (Hristov and Reynolds,

2015).

3

It encompasses information and communications tech-

nologies, supply chains and broader operational systems.

Such innovations are less visible from a customer perspec-

tive (Hristov and Reynolds, 2015).

ine the different elements that each technology brings

to the table to inform this work’s practical implica-

tions further. Three main differences were identified

based on the review presented herein:

5.2.1 Use

The fact that AR is blended with real life to scale pro-

vides the opportunity for applications to add virtual

content to the real-life context. This feels natural to

the shopping and product environment because it en-

ables virtual try-on sessions, product trials, and in-

teractions to affect purchase decisions (Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018; Catchoom, 2017). Moreover,

AR applications can offer product-related informa-

tion in context, provide after-sale services, and offer

additional customer value. These enable customers

to have their purchased products extended with new,

virtual content or get useful after-sale support. At

the organizational level, AR applications can facili-

tate management processes that utilize and can bene-

fit from the aforementioned functionality, i.e., adding

virtual content to real-life context (Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018; Catchoom, 2017). However, VR can

create fully immersive experiences in virtually simu-

lated spaces with high emotional engagement. At the

sales level, VR is presented as being used more as a

tool for branding and evoking the “wow factor” than

as a tool for creating customer value and/or support-

ing after-sale stages. At the organizational level, VR

can create high-quality training environments, sim-

ulating various scenarios that would be challenging

to recreate in real life (Boletsis and Karahasanovic,

Immersive Technologies in Retail: Practices of Augmented and Virtual Reality

287

2018; Catchoom, 2017; Biocca and Delaney, 1995;

Farah et al., 2019).

5.2.2 Technology Penetration

Figure 1 shows a much wider penetration of AR in

retail compared with VR. The main reason might

be that AR is easier to scale across users because

it can be experienced from many devices, such as

smartphones, tablets, desktop PCs, and AR glasses

(Catchoom, 2017). That scalability also affects the

cost of implementing AR projects in retail by keep-

ing costs low. However, VR is challenging to scale

because of the need for a specific user device (i.e.,

VR headset). Moreover, VR remains a largely under-

used tool due to its considerable high cost, the physi-

cal space needed for interaction, and user familiarity,

i.e., several users may not be completely familiar with

VR technology and the new devices, thus limiting

its target group (Boletsis and Karahasanovic, 2018;

Catchoom, 2017; Farah et al., 2019).

5.2.3 Sales Channels

The findings show that AR innovations can easily fa-

cilitate the integration of sales channels operating at

the pre-sale stage. These innovations can be inte-

grated easily into customer purchase journey through

scan-to-shop applications and instant actions to buy.

AR applications bridge the gap between physical and

online shops, providing the best of both worlds (Bo-

letsis and Karahasanovic, 2018; Catchoom, 2017).

However, VR is more difficult to integrate across sales

channels and, its direct impact on sales is more dif-

ficult to demonstrate because VR shopping remains

in its infancy. Nevertheless, important steps are be-

ing taken in this direction (e.g., Alibaba Buy+, IKEA

Virtual Reality Store) (Wu et al., 2018; Boletsis and

Karahasanovic, 2018; Catchoom, 2017). It should

be noted that both technologies – based on the afore-

mentioned current and scheduled advances – can pos-

itively affect the way people perceive shopping and

perform shopping activities, especially during times

or situations in which physical shopping may be a

challenging task (e.g., for people with physical dis-

abilities or during pandemics).

5.2.4 Summary

Overall, AR is widely used in the retail environment.

Its main advantage is that it can display digital infor-

mation on the real place, thus making it ideal for pur-

chase journeys and workflow management. Its imple-

mentation can be inexpensive and easily scalable at

the same time. Consequently, it can be said that AR is

of high practical value for retailing. VR is more diffi-

cult to implement in retail since it can be more expen-

sive and is cumbersome – so far – to integrate with

the sales channel; however, it can create strong emo-

tional engagement due to high immersion and can be

a useful tool for branding and training. Therefore, the

practices of these two technologies in retail and their

strengths can supplement each other, thereby creat-

ing promising innovation strategies when combined,

such as in the case of IKEA (Edvardsson and Enquist,

2011).

5.3 Research Limitations

This study contains certain limitations. The AR/VR

applications that were included and documented

herein were commercial applications, but they had to

have been presented in peer-reviewed research pub-

lications. As explained in Section 3.2, this method-

ological choice aimed to ensure that we included re-

liable AR/VR applications and not theoretical con-

cepts or prototypes. However, by introducing this

research-related criterion some applications that ex-

ist in the market but are not included in peer-reviewed

research publications may have been left out. Still,

the total number of reviewed applications (N=28) can

be viewed as adequate for providing a representative

overview of current AR/VR-enabled retail practices.

Moreover, the innovation elements that the two

technologies introduce are discussed briefly in Sec-

tion 5.1 because the technologies’ contribution to re-

tail innovation is analyzed and discussed at length

in our previous publication (cf. (Boletsis and Kara-

hasanovic, 2018)), utilizing the “Ten Types of Inno-

vation” business framework by Keeley et al. (2013).

As stated in Section 1, this study extends our previous

innovation-centric paper, focusing more on the tech-

nological contributions of AR and VR to retail.

6 CONCLUSION

Current work demonstrated that retail companies ac-

tively use AR/VR at different stages of the retail pro-

cess to achieve their business goals. The two tech-

nologies, despite operating on the same continuum,

can offer different values to retail practices, and these

characteristics were captured in this study. Therefore,

we consider that the theoretical knowledge produced

in this work can guide retail practice and shed more

light on how companies are using AR/VR in retail,

thus informing their future strategies.

Nevertheless, the work presented here is descrip-

tive and a prescriptive approach is needed in future re-

WUDESHI-DR 2020 - Special Session on User Decision Support and Human Interaction in Digital Retail

288

search. Future work will entail a systematic literature

review around the use of AR and VR in retail, map-

ping the reviewed AR/VR applications further by in-

troducing more aspects (wherever available), such as

cost and profitability. The goal of future work will be

the synthesis of novel theoretical knowledge, such as

design guidelines, process models, or decision frame-

works to inform retailers about the benefits from uti-

lizing AR and VR and guide them regarding the im-

plementation of AR/VR applications.

REFERENCES

Avila, L. and Bailey, M. (2016). Augment your reality.

IEEE computer graphics and applications, 36(1):6–7.

Azuma, R. T. (1997). A survey of augmented real-

ity. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments,

6(4):355–385.

Babu, A. R., Rajavenkatanarayanan, A., Abujelala, M., and

Makedon, F. (2017). Votre: A vocational training and

evaluation system to compare training approaches for

the workplace. In International Conference on Vir-

tual, Augmented and Mixed Reality, pages 203–214.

Springer.

Baier, D., Rese, A., and Schreiber, S. (2015). Analyzing on-

line reviews to measure augmented reality acceptance

at the point of sale: the case of ikea. In Successful

Technological Integration for Competitive Advantage

in Retail Settings, pages 168–189. IGI Global.

Balaji, M., Roy, S. K., Sengupta, A., and Chong, A. (2018).

User acceptance of iot applications in retail industry.

In Technology Adoption and Social Issues: Concepts,

Methodologies, Tools, and Applications, pages 1331–

1352. IGI Global.

Beecham, S., Baddoo, N., Hall, T., Robinson, H., and

Sharp, H. (2008). Motivation in software engineer-

ing: A systematic literature review. Information and

software technology, 50(9):860–878.

Billinghurst, M., Clark, A., Lee, G., et al. (2015). A survey

of augmented reality. Foundations and Trends

R

in

Human–Computer Interaction, 8(2-3):73–272.

Biocca, F. and Delaney, B. (1995). Immersive virtual real-

ity technology. Communication in the age of virtual

reality, 15:32.

Bodhani, A. (2013). Getting a purchase on AR. Engineer-

ing & Technology, 8(4):46–49.

Boletsis, C. (2017). The new era of virtual reality locomo-

tion: a systematic literature review of techniques and

a proposed typology. Multimodal Technologies and

Interaction, 1(4):24:1–24:17.

Boletsis, C. and Karahasanovic, A. (2018). Augmented re-

ality and virtual reality for retail innovation. Magma-

Tidsskrift for økonomi og ledelse, 7:49–59.

Bonetti, F. and Perry, P. (2017). A review of consumer-

facing digital technologies across different types of

fashion store formats. In Advanced fashion technol-

ogy and operations management, pages 137–163. IGI

Global.

Bonetti, F., Warnaby, G., and Quinn, L. (2018). Augmented

reality and virtual reality in physical and online re-

tailing: A review, synthesis and research agenda. In

Augmented reality and virtual reality, pages 119–132.

Springer.

Bresciani, L. and Ewing, M. (2015). Brand building in the

digital age: The ongoing battle for customer influence.

Journal of Brand Strategy, 3(4):322–331.

Caboni, F. and Hagberg, J. (2019). Augmented reality in

retailing: a review of features, applications and value.

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Man-

agement, 47(11):1125–1140.

Carruth, D. W. (2017). Virtual reality for education and

workforce training. In 2017 15th International Con-

ference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Ap-

plications (ICETA), pages 1–6. IEEE.

Catchoom (2017). Virtual vs. Augmented Real-

ity Experiences in Retail. Available online:

https://catchoom.com/blog/virtual-vs-augmented-

reality-experiences-in-retail/. (accessed on 17 Jun

2020).

Dacko, S. G. (2017). Enabling smart retail settings via mo-

bile augmented reality shopping apps. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change, 124:243–256.

De Gauquier, L., Brengman, M., Willems, K., and Van Ker-

rebroeck, H. (2019). Leveraging advertising to a

higher dimension: experimental research on the im-

pact of virtual reality on brand personality impres-

sions. Virtual Reality, 23(3):235–253.

De Keyser, A., K

¨

ocher, S., Alkire, L., Verbeeck, C., and

Kandampully, J. (2019). Frontline service technology

infusion: conceptual archetypes and future research

directions. Journal of Service Management.

De Silva, R., Rupasinghe, T. D., and Apeagyei, P. (2019). A

collaborative apparel new product development pro-

cess model using virtual reality and augmented real-

ity technologies as enablers. International Journal of

Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 12(1):1–

11.

Dulabh, M., Vazquez, D., Ryding, D., and Casson, A.

(2018). Measuring consumer engagement in the brain

to online interactive shopping environments. In Aug-

mented Reality and Virtual Reality, pages 145–165.

Springer.

Edvardsson, B. and Enquist, B. (2011). The service ex-

cellence and innovation model: lessons from ikea and

other service frontiers. Total Quality Management &

Business Excellence, 22(5):535–551.

Farah, M. F., Ramadan, Z. B., and Harb, D. H. (2019).

The examination of virtual reality at the intersection

of consumer experience, shopping journey and physi-

cal retailing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Ser-

vices, 48:136–143.

Grewal, D., Motyka, S., and Levy, M. (2018). The evolution

and future of retailing and retailing education. Journal

of Marketing Education, 40(1):85–93.

Gryb

´

s, M. (2014). Creating new trends in international mar-

keting communication. Journal of Economics & Man-

agement, 15:155–173.

Guo, A., Wu, X., Shen, Z., Starner, T., Baumann, H., and

Immersive Technologies in Retail: Practices of Augmented and Virtual Reality

289

Gilliland, S. (2015). Order picking with head-up dis-

plays. Computer, 48(6):16–24.

Hilken, T., de Ruyter, K., Chylinski, M., Mahr, D., and

Keeling, D. I. (2017). Augmenting the eye of the be-

holder: exploring the strategic potential of augmented

reality to enhance online service experiences. Journal

of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(6):884–905.

Hilken, T., Heller, J., Chylinski, M., Keeling, D. I., Mahr,

D., and de Ruyter, K. (2018). Making omnichannel an

augmented reality: the current and future state of the

art. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing.

Hristov, L. and Reynolds, J. (2015). Perceptions and prac-

tices of innovation in retailing. International Journal

of Retail & Distribution Management.

Iyadurai, F. S. and Subramanian, P. (2016). Smartphones

and the disruptive innovation of the retail shopping

experience. In 2016 International Conference on Dis-

ruptive Innovation.

Javornik, A. (2016). Augmented reality: Research agenda

for studying the impact of its media characteristics on

consumer behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Con-

sumer Services, 30:252–261.

Jean, M. (2017). The growth of virtual reality technology

in china. In 2017 Video Games & Digital Media Con-

ference.

Keeley, L., Walters, H., Pikkel, R., and Quinn, B. (2013).

Ten types of innovation: The discipline of building

breakthroughs. John Wiley & Sons.

Kemke, C., Galka, R., and Hasan, M. (2006). Towards an

intelligent interior design system. In Proc. Workshop

on Intelligent Virtual Design Environments (IVDEs).

Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for performing system-

atic reviews. Technical Report TR/SE-0401, Keele

University and National ICT Australia Ltd.

Loureiro, S. M. C., Guerreiro, J., Eloy, S., Langaro, D., and

Panchapakesan, P. (2019). Understanding the use of

virtual reality in marketing: A text mining-based re-

view. Journal of Business Research, 100:514–530.

Man, W. and Qun, Z. (2017). The deconstruction and re-

shaping of space: the application of virtual reality in

living space. In 2017 9th International Conference on

Measuring Technology and Mechatronics Automation

(ICMTMA), pages 410–413. IEEE.

McCormick, H., Cartwright, J., Perry, P., Barnes, L., Lynch,

S., and Ball, G. (2014). Fashion retailing–past, present

and future. Textile Progress, 46(3):227–321.

Milgram, P. and Kishino, F. (1994). A taxonomy of mixed

reality visual displays. IEICE TRANSACTIONS on In-

formation and Systems, 77(12):1321–1329.

Miraldes, T., Azevedo, S. G., Charrua-Santos, F. B.,

Mendes, L. A. F., and Matias, J. C. O. (2015). It

applications in logistics and their influence on the

competitiveness of companies/supply chains. Annals

of the Alexandru Ioan Cuza University-Economics,

62(1):121–146.

Mocanu, R. (2012). Chasing experience. how augmented

reality reshaped the consumer behaviour and brand in-

teraction. Opportunities and Risks in the Contempo-

rary Business Environment, page 317.

Moorhouse, N., tom Dieck, M. C., and Jung, T. (2018).

Technological innovations transforming the consumer

retail experience: A review of literature. In Aug-

mented reality and virtual reality, pages 133–143.

Springer.

Mustafa, T., Matovu, R., Serwadda, A., and Muirhead, N.

(2018). Unsure how to authenticate on your vr head-

set? come on, use your head! In Proceedings of the

Fourth ACM International Workshop on Security and

Privacy Analytics, pages 23–30.

Olszewski, K., Lim, J. J., Saito, S., and Li, H. (2016). High-

fidelity facial and speech animation for VR HMDs.

ACM Transactions on Graphics, 35(6):221.

Poushneh, A. (2018). Augmented reality in retail: A trade-

off between user’s control of access to personal infor-

mation and augmentation quality. Journal of Retailing

and Consumer Services, 41:169–176.

Rese, A., Baier, D., Geyer-Schulz, A., and Schreiber, S.

(2017). How augmented reality apps are accepted

by consumers: A comparative analysis using scales

and opinions. Technological Forecasting and Social

Change, 124:306–319.

Rese, A., Schreiber, S., and Baier, D. (2014). Technology

acceptance modeling of augmented reality at the point

of sale: Can surveys be replaced by an analysis of on-

line reviews? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Ser-

vices, 21(5):869–876.

Satoglu, S., Ustundag, A., Cevikcan, E., and Durmusoglu,

M. B. (2018). Lean transformation integrated with in-

dustry 4.0 implementation methodology. In Industrial

Engineering in the Industry 4.0 Era, pages 97–107.

Springer.

Scholz, J. and Smith, A. N. (2016). Augmented reality:

Designing immersive experiences that maximize con-

sumer engagement. Business Horizons, 59(2):149–

161.

Steuer, J. (1992). Defining virtual reality: Dimensions de-

termining telepresence. Journal of communication,

42(4):73–93.

Verhoef, P. C., Kannan, P. K., and Inman, J. J. (2015). From

multi-channel retailing to omni-channel retailing: in-

troduction to the special issue on multi-channel retail-

ing. Journal of retailing, 91(2):174–181.

Vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Niehaves, B., Riemer, K., Plat-

tfaut, R., and Cleven, A. (2009). Reconstructing the

giant: On the importance of rigour in documenting

the literature search process. In Proceedings of the

European Conference on Information Systems, pages

2206–2217.

Wu, J., Joo, B. R., and Sina, A. S. (2018). Personalizing

3d virtual fashion stores: Module development based

on consumer input. Back to the Future: Revisiting the

Foundations of Marketing, page 296.

Yim, M. Y.-C., Chu, S.-C., and Sauer, P. L. (2017). Is

augmented reality technology an effective tool for e-

commerce? an interactivity and vividness perspective.

Journal of Interactive Marketing, 39:89–103.

Zhao, Z. and Balagu

´

e, C. (2017). From social networks to

mobile social networks: applications in the market-

ing evolution. In Apps management and e-commerce

transactions in real-time, pages 26–50. IGI Global.

WUDESHI-DR 2020 - Special Session on User Decision Support and Human Interaction in Digital Retail

290