Access Barriers of Infertility Services for Urban and Rural Patients

Binarwan Halim, Ermi Girsang*, Sri Lestari R. Nasution, Chrismis Novalinda Ginting

Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Prima Indonesia, Indonesia

Keywords: Access Barriers, infertility, urban, rural.

Abstract: The infertility problem is faced by 15-20% of couples of childbearing age that have an impact on couples

social and psychological problems, families and communities. Infertility services in Indonesia are not well

distributed and most are in urban areas. The infertility services in rural areas are normally difficult to access.

This study aims to detect differences in barriers to access the infertility services in urban and rural

communities who seek treatment at IVF Clinic. The study was conducted by quantitative methods using a

questionnaire. A total of 130 respondents were divided into two groups each 65 respondents for rural and

urban, respectively. The analyzed variables include knowledge, economic status, geography, social culture,

psychological, and religious. The data obtained were analyzed by chi-square and multivariate. It was found

three out of six significant variables (p = 0.014, p = 0.023 and p = 0.005) in multivariate analysis which are

the economic level, geographic location, and socio-cultural with an OR values of 2.606, 3.905, and 5.299,

respectively. The economic status in urban areas was higher than rural, geographical barriers in rural areas

were more than urban, and socio-cultural barriers with less support in rural compared to urban areas.

1 INTRODUCTION

Infertility is the failure of a partner to get pregnant at

least within 12 months of having sex regularly

without contraception. Infertility problems can have

a major impact on married couples who experience

them, in addition to causing medical problems,

infertility can also cause economic and psychological

problems (HIFERI, 2013). Normally, couples who

experience infertility will go through a long process,

where this process can be a physical and

psychological burden for infertility couples (Irianto,

2014). Fertility or fertility of a person can be

influenced by genetics, heredity, and age. The

infertility is classified into two types, namely primary

and secondary infertilities (Anwar, 2005).

The problem of infertility is not only a

gynecological problem, but it becomes a serious

health problem because these problems often affect

the quality of life, not only on the physical but also

have an impact on the psychological, social and

economic of the individuals and couples.

9,10,11

In the United States, health service gaps also

occur in infertility services. High medical costs,

barriers to access of services cause problems in

getting fertility services. The majority of patients

undergoing treatment with the Invitro Fertilization

(IVF) method in the United States pay for themselves

because they do not have health insurance that covers

IVF costs (Wu et al., 2014). Other factors that

contribute to barriers to access of the infertility

services are the level of education and knowledge,

race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender

identity, marital status, and conscious or unconscious

discrimination (Peterson, 2005; Bennett et al. ., 2012;

Harzif et al., 2019; Thompson, 2006; Domar et al.,

2005).

Harris et al. (2017) and Chin et al. (2017) found

that geographical influence on access to infertility

services (Harris et al., 2017; Chin et al., 2017). Ho et

al. (2017) and Udgiri et al. (2019) found a socio-

cultural influence on access to infertility services (Ho

et al. 2017; Udgiri et al. 2019). Economic barriers in

the form of large income also affect access to

infertility services where financial support such as

health insurance is needed especially in rural

communities with lower economic status (Insogna et

al., 2018; Maxwell et al., 2017; Kaur et al., 2018 ;

Kunicki et al., 2018). Psychological conditions are

also reported to be one of the barriers to access

infertility services (Lakatos et al, 2017; Rooney et al,

2018; Omu et al, 2010; Turnip et al, 2020; Wijaya,

2019). Lakatos et al. (2017) and Rooney et al. (2018)

reported that symptoms of depression and anxiety in

Halim, B., Girsang, E., R. Nasution, S. and Ginting, C.

Access Barriers of Infertility Services for Urban and Rural Patients.

DOI: 10.5220/0010291901490157

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics, Medical, Biological Engineering, and Pharmaceutical (HIMBEP 2020), pages 149-157

ISBN: 978-989-758-500-5

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

149

infertile women were more prominent than fertile

women (Lakatos et al., 2017; Rooney et al., 2018).

Various psychological responses appear in

couples who are facing infertility problems, including

low self-esteem, anger, sadness, jealousy towards

other couples who already have children, anxiety,

and, finally, depression (Wiweko et al. 2017).

Wiweko et al. (2017) found that the distribution of the

stress levels in infertile patients in the Yasmin IVF

Clinic in Indonesia accounts for 22% of the risk

factors for infertility, which are mainly associated

with the length of infertility. These symptoms are

physical symptoms and interfere with the couple’s

daily activities (Wiweko et al. 2017).

World Health Organization (WHO) and the

United Nations have made reproductive health a

global health care priority. Encouragement needs to

be given so that all stakeholders are moved to build

affordable, safe and effective infertility services

(Ethics Committee of the ASRM, 2015). Another

problem is that most regions in the world that have

high infertility rates find it difficult to access

infertility clinics that are rare and expensive, so that

most women become less concerned about their

future without children (Inhorn et al., 2014). Only

about 25% of infertile couples are able to access

infertility services both in developed and developing

countries (Sadeghi, 2015). The prevalence of

infertility according to the WHO is estimated at 8-

10%. Most infertile couples exist in developing

countries (Ombelet, 2011). The infertility rate in

Indonesia ranges from 12-15% or around 3 million

couples (Fauziah, 2012). The normal, young aged

couples have a 25% chance to conceive after 1 month

of unprotected intercourse; 70% of the couple’s

conceive by 6 months, and 90% of the couples have a

probability to conceive by 1 year (Anwar et al., 2016).

Indonesia has 34 fertility clinics that offer a

variety of treatment options, but the use of these

facilities is still very low. This is reflected in the

number of IVF cycles per year in Indonesia which is

still very low compared to other countries. The reason

is that fertility clinics tend to be centered in big cities,

especially in Java, and the distribution of patients and

the IVF cycle are not compatible with existing clinics

(Ombelet, 2011). Based on the 2017 IDHS, fertility

rates in North Sumatra declined from 3% in 2012 to

2.9% in 2017. In other words, infertility rates have

increased every year in North Sumatra (BKKBN,

2017). One of the fertility clinics in North Sumatra,

the Halim Fertility Center, has also seen an increase

in new patient visits each year where the average

number of new patient visits each year is 1300

patients. However, the use of existing infertility

clinics is still inadequate and referrals are still low.

The referral system from other health providers to

fertility service facilities is very influential (Klitzman,

2018).

Several attempts have been made to improve

access to infertility services in Indonesia. Bennett et

al. (2012) in his research found that there are four

keys that must be done to improve access to infertility

services in Indonesia, among others, improving

education and counseling, improving the referral

system, reducing medical costs and equitable fertility

service facilities. (Bennett et al., 2012). Harzif et al.

(2019) concluded that providing information about

infertility services to the community was proven to

increase patient acceptance of the treatment to be

provided (Harzif et al., 2019). The barriers to access

faced by infertility patients to reach the fertility clinic

can be different when viewed from the origin of the

patient, whether coming from urban or rural areas.

The barriers can be various factors such as

knowledge, geographical, socio-cultural, religious,

economic andpsychological barriers.

This study aims to determine various variations of

the obstacles faced by urban and rural communities,

so that with the results of this study, researchers can

map the strategy approach to help infertility patients

so they can get offspring. This study is different from

previous studies because the samples taken came

from patients visiting IVF clinics to find out more

clearly the characteristics and influential factors in

relation to their visits to IVF clinics so that solutions

can be found for more optimal infertility services.

2 METHOD

In this study, data collection was carried out using a

closed questionnaire in the form of multiple choices

with each question having a choice of 2-5 answers (a

total of 42 questions consisting of 5 questions of

respondents' identities and 37 questions including

knowledge of fertility, economic status, geography,

psychological, sociocultural and religious). We have

checked the existence of such a questionnaire before

designing new questionnaire but we did not find the

questionnaire and we designed our own questionnaire

about access barriers of infertility services.

The questionnaire consisted of six sections: First,

it included personal and demographic data (age,

marriage time, education levels, occupations). The

second section was concerning women’s knowledge

of infertility and its management. It consisted of 20

single and multiple response questions about the

definition, duration, etiology, and treatment of

HIMBEP 2020 - International Conference on Health Informatics, Medical, Biological Engineering, and Pharmaceutical

150

infertility. The next section was related to economic

status as a barrier to access, which consisted of 4

single questions about monthly income, knowledge

of how much infertility treatment cost, financial

ability, and hold health insurance to cover their

infertility treatment. The fourth section was related to

patient’s geographical barrier with 5 single questions

on accessibility to infertility care which consisted of

4 single questions about knowledge of availability of

fertility clinic in North Sumatera, the distance

between patients residence and fertility care,

availability of transportation to fertility care, and the

severity of the transportation field. Then, the fifth

section was about a patient’s psychological and

emotional barriers consist of 3 single questions about

fear of infertility treatment, an embarrassment of

being infertility couple, the embarrassment of

infertility treatment. Finally, the last section was

about socio-cultural factors which also consisted of 4

single questions about their beliefs and culture related

to infertility treatment, family endorsement for

infertility treatment, and gender of the medical

provider.

The questionnaire used first tested the validity

with Pearson product moment correlation coefficient,

called valid if the value is above 0.30. The valid

questions continue with the Cronbach’s alpha

reliability test. (reliable if the value is above 0.619).

The study was conducted at Halim Fertility Center

IVF Clinic at Stella Maris Hospital from August until

October 2019. The study population was patients

from IVF Clinic with an average visit of 1300 patients

/ year and with total sample was 130 patients.

Research samples that meet the inclusion criteria are

infertility >1 year, willing to participate as

respondents, able to communicate well, physically

and mentally. Exclusion criteria are if the

questionnaire answers are incomplete where there are

130 respondents who are divided into 2 groups

namely urban and rural. The sampling technique used

was consecutive sampling, where every new patient

who came during the study period was used as a

sample. We obtained the ethical clearance from the

hospital. Patients who are willing to become

respondents are asked to sign a willingness form to

participate in the study and are notified that the results

of the research will be published later. We perfomed

validity and reliability test to the questionnaire. The

validity test was conducted on 20 respondents at

Sarah General Hospital Medan and the research tool

in the form of researchers conducted interviews

directly with patients and read out the research

questions listed in the questionnaire. The independent

variables of this study were barriers of access to

infertility ( knowledge, economy, geographical,

psychological, social culture and religious) and

dependent variables were urban and rural patients.

Bivariate test analysis uses chi-square test for two-

parameter data and Kruskal Wallis for data of more

than two parameters, while multivariate data analysis

to determine correlations uses multiple logistic

regression tests. The results are presented in narrative

form in accordance with the related theory (figure 1).

Figure 1. Scheme of Research Process

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1 Validity and Reliability Tests

This study uses a questionnaire that has been tested

for validity using the Pearson product moment test.

Where if r count (rc)> r table (rt) (> 0.3) then the

question was declared valid. In Table 1, shows from

20 items of knowledge questions obtained 12 valid

items and 8 invalid. There were a number of

questions for Economic, geography, psychology,

social cultural, and religious variables (i.e., 5, 5, 3, 2,

and 2, respectively) which all of them were valid. The

detail validity tests results for each variable is shown

in Table 1, where K is Knowledge; E is Economy; G

is Geography; P is Psychology; S is Social Culture;

and R is Religious.

Access Barriers of Infertility Services for Urban and Rural Patients

151

Table 1. Validity Test Result of Knowledge, Economics, Geography, Pyschology, Social Culture, and Religion.

N

o K No K E G P S R

rc rt v rc rt v rc rt v rc rt v rc rt v rc rt v rc rt v

1

0

.269 0.361 - 11

0

.61

5

0.361 + 0.641 0.361 + 0.724

0

.36

1

+

0

.81

5

0

.36

1

+

0

.33

1

0

.36

1

+

0

.64

9

0

.36

1

+

2

0

.374 0.361 + 12

0

.39

6

0.361 + 0.815 0.361 + 0.821

0

.36

1

+

0

.52

6

0

.36

1

+

0

.41

3

0

.36

1

+

0

.88

1

0

.36

1

+

3

0

.423 0.361 + 13

0

.37

7

0.361 + 0.375 0.361 + 0.815

0

.36

1

+

0

.45

8

0

.36

1

+

4

0

.268 0.361 - 14

0

.48

0

0.361 + 0.424 0.361 + 0.458

0

.36

1

+

5

0

.261 0.361 - 15

0

.28

4

0.361 - 0.815 0.361 + 0.424

0

.36

1

+

6

0

.154 0.361 - 16

0

.45

1

0.361 +

7

0

.144 0.361 - 17

0

.64

4

0.361 +

8

0

.384 0.361 + 18

0

.21

3

0.361 -

9

0

.375 0.361 + 19

0

.48

8

0.361 +

10

0

.424 0.361 + 20

0

.11

4

0.361 -

Table 2 is the reliability test results for each observed

variable. From Table 2 it can be seen that the results

of the reliability test on the questionnaire questions

regarding knowledge, economics, geography,

psychology, social culture and religious are reliable

because the Cronbach Alpha value >0.6.

Table 2. Reliability Test Results of Knowledge, Economics,

Geography, Psychology, Social Culture, and Religion.

Variables Cronbach`s

Alpha

Qty

Knowled

g

e 0.633 20

Economics 0.691 5

Geo

g

ra

p

h

y

0.687 5

Ps

y

cholo

gy

0.676 3

Social Culture 0.667 2

Reli

g

ious 0.654 2

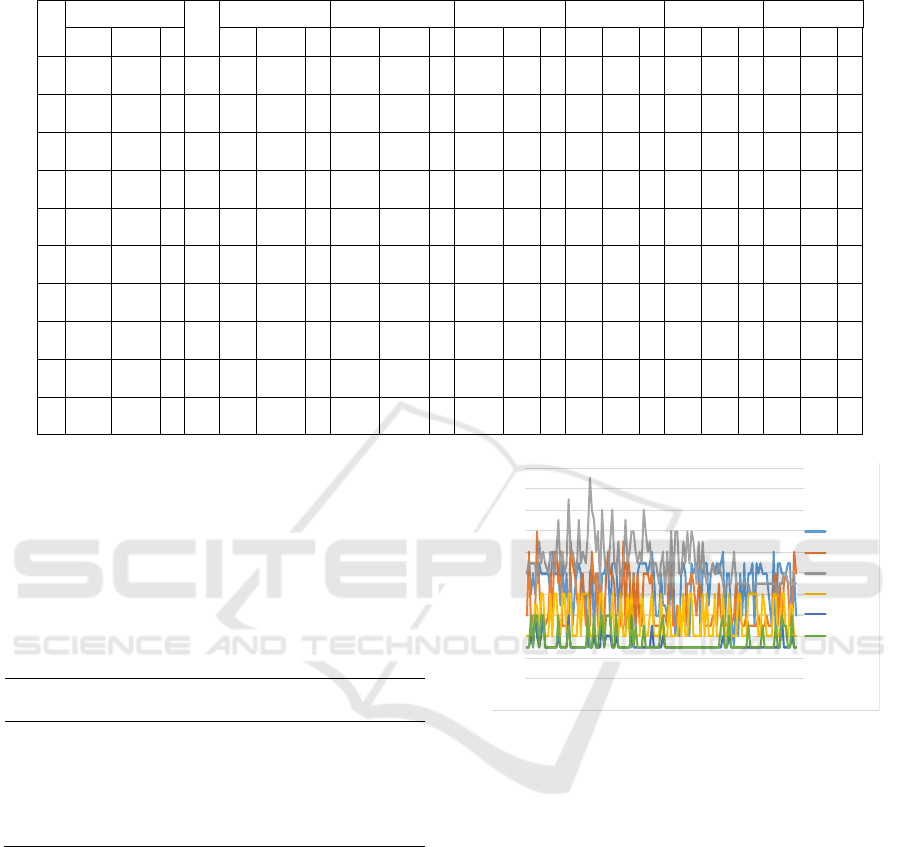

Figure 2 shows the results of variable data from

130 respondents (urban: 1-65 and rural: 66-130). The

X-axis is the number of scores and the Y-axis is the

number of respondents. Light blue, orange, gray,

yellow, dark blue, and green colors are the variables

of knowledge, economic status, geography,

psychology, social culture, and religion with less,

low, there are obstacles, worries, less supportive, and

conflicting variables if scores ≤ 9, ≤6, ≤ 13, ≤4, ≤3,

and ≤3, respectively, and vice versa if the score is

greater.

Figure 2. Measurement results for 130 respondents for each

variable.

3.2 Bivariate Analysis

Table 3 shows the distribution of characteristics of

urban and rural respondents. Of the 130 respondents

in both the urban and rural groups, the majority of

respondents were <35 years old, namely 73.8% and

64.6%; for long time married, urban groups were

found 1-3 years as much as 35.4% and rural groups

were found >5 years as much as 50.8%. In terms of

education characteristics, the majority of urban and

rural groups have Bachelor /Magister/ Doctoral

degree educations, namely 81.5% and 76.9%, in

terms of employment, urban and rural groups have

housewives and other jobs as many as 47.7% and

63.1% Working conditions, the majority in the urban

and rural groups have leave of 83.1% and 75.4%.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

1

7

13

19

25

31

37

43

49

55

61

67

73

79

85

91

97

103

109

115

121

127

133

Total

Score

Knowledge

Economics

Geography

Psychology

Social

Culture

Religious

HIMBEP 2020 - International Conference on Health Informatics, Medical, Biological Engineering, and Pharmaceutical

152

Table 3. Distribution of Characteristics of Urban and Rural

Respondents.

Characteristics

Urban Rural

n

(65)

%

(100)

n

(65)

%

(100)

Age (years)

< 35 48 73.8 42 64.6

> 35

17 26.2 23 35.4

Marriage time

< 1 5 7.7 6 9.2

1-3 23 35.4 17 26.2

4-5 15 23.1 9 13.8

> 5 22 33.8 33 50.8

Educations

Junio

r

&High School 12 18.5 15 23.1

Bachelor/Magister/

Doctoral Degree

53 81.5 50 76.9

Occupation

Private 28 43.1 14 21.5

Official Governmen

t

6 9.2 10 15.4

House wive&Others 31 47.7 41 63.1

Factors affecting access to infertility services in

this study are the level of knowledge, economic,

geographical, psychological / emotional, socio-

cultural, and religious levels (Table 4). Based on the

level of knowledge of respondents obtained the

results of statistical tests using the Chi Square test

there were no significant differences in the level of

knowledge of urban and rural groups (p = 0.453).

Based on the perspective level of the knowledge

about the fertility of the two groups does not have a

significant difference, on average have enough good

knowledge. This can be explained because the

samples taken were patients who come for treatment

at IVF clinics, which in general have already done a

lot of searching information and knowledge both

from the internet, social media, as well as by word of

mouth and the internet has been able to reach remote

areas, so rural communities also easily access

information and knowledge about fertility. This is

different with Harzif et al. (2019) found that

populations in urban and rural areas have

misperceptions about infertility, negative behavior

and inadequate knowledge. This might be due to

differences in the sample of patients taken and the

types of questions given in the questionnaire which

may have different weights (Harzif et al., 2019). The

study took samples from populations directly in

villages and cities and not those who came to the IVF

clinic.

The rural group had a lower economic level of

70.8% compared to the urban group of 49.2%.

Statistical test results at the economic level found

significant differences between urban and rural

groups (p=0.012). The level of income in the rural

group was significantly lower than in urban areas, it

is understandable that usually the rich live more in

cities. Of course, this economic ability influences

access to fertility treatment which is quite expensive.

In the rural group (92.3%) more expressed

geographical barriers compared to the urban group

(76.9%). From the statistical test results obtained a

significant difference in geographical factors between

urban and rural groups (p=0.015). When viewed from

geographical barriers, it clearly shows groups

especially those far from the center overcoming

fertility will experience difficulties. Fertility

treatment requires repeated visits and requires a

significant amount of time. This will also affect the

level of employment, economy and costs.

In psychological / emotional factors, both rural

and urban, groups that experienced more feelings of

worry than those who were not worried were rural as

much as 61.5% and urban as much as 60%. But from

the results of statistical tests there were no significant

differences at the psychological / emotional level

between urban and rural groups (p=0.857). Basically

a person has a feeling of shame or worry about

fertility conditions, especially when under pressure

from family, neighborhood or work environment. The

diagnosis of infertility can be a tremendous burden on

patients. The pain and suffering of infertility patients

is a major problem. Patients should be counseled and

supported when they undergo treatment (Lakatos et

al., 2017; Rooney et al., 2018). The burden of the

mind makes someone feel worried and maybe even

stressed in doing fertility treatments.

From the socio-cultural perspective, it was seen in

the rural and urban groups that more complained that

they experienced obstacles, namely 92.3% and

75.4%, respectively. Statistical test results on socio-

cultural factors found significant differences in socio-

culture between urban and rural groups (p = 0.009).

In rural groups more than urban areas, the level of

public trust in fertility services was still lacking, there

were still some worried that later offspring will not be

produced from their flesh and blood because they

were afraid of using other people's gamete cells.

Moreover, there was public trust in fertility services

was still lacking, there were still some worried that

later offspring will not be produced from their flesh

and blood because they were afraid of using other

people's gamete cells. Moreover, there was public

trust in raising infertility as karma due to errors made

by his family.

In the rural group about 83.1% who stated

contrary to religious while the urban group as much

as 70.8%. From the results of statistical tests, no

significant differences were found in groups facing

religious barriers between urban and rural groups

Access Barriers of Infertility Services for Urban and Rural Patients

153

(p=0.096). Basically the environment in Indonesia

both in cities and villages, the influence of religious

in family life is still large, many still consider children

a gift from God, if God still does not allow it, the

spouse still will not be able to have children. In

another study, there were religious barriers where the

IVF program was considered to be in conflict with the

religious and the values of the beliefs of the local

community (Thompson et al., 2006; Domar et al.,

2005).

Table 4. Proportions Distribution of Factors Affecting

Access to Infertility Services

Factors

Urban Rural p

n

%

n

%

Knowledge

Good 46 70.8 42 64.6

0.453

a

N

ot Good 19 29.2 23 35.4

Economics

Status

Low 32 49.2 46 70.8

0.012

a

High 33 50.8 19 29.2

Geographic

With barries 50 76.9 60 92.3

0.015

a

Without barriers 15 23.1 5 7.7

Psychological

Worry 39 60.0 40 61.5

0.857

a

N

o Worry 26 40.0 25 38.5

Socio-cultural

Less Supported 49 75.4 60 92.3

0.009

a

Supported 16 24.6 5 7.7

Religious

Contradicting 46 70.8 54 83.1

0.096

a

N

ot contradicting 19 29.2 11 16.9

a=Chi-Square

Table 5 shows the results of multivariate analysis

using multiple logistic regression tests. The variables

that qualify for testing (p<0.25) are economic,

geographic, socio-cultural, and religious. Based on

the results of statistical tests it is known that there are

three significantly different variables (p = 0.014; p =

0.023 and p = 0.005) in multivariate analysis, namely

the economic level with an OR value of 2.606 (95%

CI 1.210-5.611), geographic location an OR value of

3.905 ( 95% CI 1.203-12.677), and socio-cultural

with an OR value of 5.299 (95% CI 1.659-16.929),

while religious variables did not differ significantly

(p> 0.05). Thus it can be concluded that barriers in

economic level, geographical and socio-cultural

location differ in urban and rural patients in access to

infertility services at IVF Clinic.

Study by Deatsman et al. showed that

Ages

ranged from 18 to 67. One third (30.5%) were aware

fertility begins to decline at age 35, however this

varied among groups depending on prior history of

infertility or requiring fertility treatment. Nulliparous

women were more unaware of the health risks of

pregnancy over age 35 (1.4% vs 13.6%, P 0.02).

African Americans (AA) women were less likely to

think obesity (76% Caucasian vs 47.8% AA vs 66.7%

other, P < 0.05) and older age (88% Caucasian vs

60.9% AA vs 82.7% other, P 0.02) affected fertility

(Deatsman et al., 2016).

Table 5. Multivariate Analysis

Variables Coefisients p OR 95% CI

Selection 1

Economics 0.965 0.014 2.625 1.216-5.669

Geography 1.362 0.023 3.905 1.205-12.653

Socio-cultural 2.026 0.018 7.583 1.412-40.727

Religious -0.404 0.559 0.668 0.172-2.589

Constant -2.184 0.001 0.113

Selection 2

Economics 0.958 0.014 2.606 1.210-5.611

Geography 1.362 0.023 3.905 1.203-12.677

Socio-cultural 1.668 0.005 5.299 1.659-16.929

Constant -2.187 0.001

P =Probability; OR=Odd Rasio; CI=confidence interval.

Roupa et al examined 110 infertile women and

found that regarding marital status 94.4% (106) of the

participants were married and 3.6% (4) unmarried.

Regarding age, 64.5% were 20–29 years old, 20.0%

were 30-39 years old, 11,8% were 40-49 years old

and 3.7% were over 50 years old. As to occupation

status, 35% of the participants were employees in the

private sector, 27% were employees in the public

sector, 24% were self employees and 14% dealt with

the household. Regarding educational status, 3.6%

had finished primary school, 31.8% had finished high

school, 56.4% were University graduates and 8.2%

were graduates of another school (Roupa et al., 2009).

Socioeconomic status (SES) is an important social

determinant that can have profound impacts on

reproductive health. In the last decades, populations

of urban and rural regions have been subject to

categorization by various means of measuring SES. A

number of socioeconomic factors such as the

woman’s educational status, income per capita,

having a job, age at first marriage, life expectancy,

and infant mortality rates have been reported to be

associated with fertility rates by social scientists. In

recent years, the serum level of AMH has been

HIMBEP 2020 - International Conference on Health Informatics, Medical, Biological Engineering, and Pharmaceutical

154

considered a new marker of ovarian reserve. It is

influenced by age and exhibits a declining trend until

a woman reaches menopause. Both ovarian reserve

parameters, namely anti-Mullerian hormone level and

antral follicle count, exhibited a sig¬nificant

association with socioeconomic status (p=0.000 and

p=0.000, respectively). The association between

follicle stimulating hormone level and socioeconomic

status was also significant (p=0.000) (Barut et al.,

2016).

Reports also link fertility transition to

socioeconomic development. In 1993–94, 36% of the

population in India lived below the poverty line and

this rate dropped to 22% in 2005–2006, and this drop

was linked to the socioeconomic development. In

addition to a declining poverty rate, the fertility rate

declined from 3.5 to 2.9 among Indians in the same

time period (Barut et al., 2016).

Ali et al. in their study found that correct

knowledge of infertility was found to be limited

amongst the participants. Only 25% correctly

identified when infertility is pathological and only

46% knew about the fertile period in women’s cycle.

People are misinformed that use of intra-uterine

device (IUD) (53%) and oral contraceptive Pil

(OCPs) (61%) may cause infertility. Beliefs in evil

forces and supernatural powers as a cause of

infertility are still prevalent especially amongst

people with lower level of education. Seeking

alternative treatment for infertility remains a popular

option for 28% of the participant as a primary

preference and 75% as a secondary preference. IVF

remains an unfamiliar (78%) and an unacceptable

option (55%). Social stigma regarding infertility is

especially common across South Asia. For e.g. in

Andhra Pradesh, India 70% of women experiencing

infertility reported being punished with physical

violence for their failure. Women are verbally or

physically abused in their own homes, deprived of

their inheritance, sent back to their parents,

ostracized, looked down upon by society, or even

have their marriage dissolved or terminated if they are

unable to conceive (Ali et al., 2011).

Roudsari et al. in their study examined religion

impact women’s prespective of infertily. Religion and

spirituality are a fundamental part of culture and

influence how individuals experience and interpret

infertility counseling. Emerging categories included:

Appraising the meaning of infertility religiously,

applying religious coping strategies, and gaining a

faith-based strength. These were encompassed in the

core category of ‘relying on a higher being’.

Religious infertile women experienced infertility as

an enriching experience for spiritual growth. This

perspective helped them to acquire a feeling of self

confidence and strength to manage their emotions.

Hence, they relied more on their own religious coping

strategies and less on formal support resources like

counselling services. However, they expected

counsellors to be open to taking time to discuss their

spiritual concerns in counseling sessions. In addition

to focusing on clients’ psychosocial needs, infertility

counsellors should also consider religious and

spiritual issues. Establishing a sympathetic and

accepting relationship with infertile women will

allow them to discuss their religious perspectives,

which consequently may enhance their usage of

counselling services (Roudsari et al., 2011).

4 CONCLUSIONS

The results of the study of 65 respondents with 6 test

variables (ie, knowledge, economic status,

geography, social culture, psychological, and

religious) found that: (i) No significant differences

were found in the obstacles in the level of knowledge,

emotional / psychological level and religious between

the two urban and rural groups (p = 0.453; p = 0.857;

p = 0.096). (ii) Significant differences were found in

the barriers to economic, geographical and socio-

cultural status between urban and rural groups (p =

0.014; p = 0.023; p = 0.005). (iii) The most significant

correlations in rural access barriers compared to

urban areas are economic, geographical and socio-

cultural (OR 2.606; OR 3.905; OR 5.299).

From this study, we can map some strategies to

help infertility patients, for instance making

telemedicine to overcome geographical barriers,

improving the referral system and reducing medical

costs to overcome economic barrier.

REFERENCES

Ali, S., Sophie R., Imam AM., Khan FI., Ali SF., Shaikh A;

Farid-ul-Hasnain S., 2011. Knowledge, perceptions and

myths regarding infertility among selected adult

population in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study, BMC

Public Health; 11:760.

Anwar S., Anwar A., 2016. Infertility: A Review on

Causes, Treatment and Management, Women’s Health

Gynecol; 2(6): 1-5.

Anwar, R., 2005. Diagnostik Klinik Dan Penilaian

Infertilitas. In: Fertilitas Endokrinologi Reproduksi

Bagian Obstetri dan Ginekologi RSHS/FKUP

Bandung, Bandung Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas

Padjajaran.

Access Barriers of Infertility Services for Urban and Rural Patients

155

Barut, MU., Agacayak E., Bozkurt M., Aksu T., Gul T.,

2016. There is a positive correlation between

socioeconomic status and ovarian reserve in women of

reproductive age, Med Sci Monit; 22: 4386-4392

Bennett, LR., Wiweko, B., Hinting, A., et al., 2012.

Indonesian infertility patients’ health seeking behaviour

and patterns of access to biomedical infertility care: An

interviewer administered survey conducted in three

clinics, Reprod Health; 9: 1.

BKKBN., 2017. Survei Demografi dan Kesehatan

Indonesia (SDKI) 2017. Jakarta.

Chin, HB., Kramer, MR., Mertens, AC., Spencer, JB.,

Howards, PP., 2017. Differences in Women's Use of

Nedical Hepl for Becoming Pregnant by the level of

urbanization of county of residence in Georgia, J Rural

health ;33(1):41-49.

Deatsman S; Vasilopoulos T; Vlasak AR., 2016. Age and

Fertility: A Study on Patient Awareness, JBRA Assisted

Reproduction; 20(3): 99-106.

Domar, AD., Penzias, A., 2005. The stress and distress of

infertility: Does religion help women cope?., Sexuality,

Reproduction & Menopause;3(2):45-51.

Ethics Committee of the American Society for

Reproductive Medicine (ASRM)., 2015. Disparities in

access to effective treatment for infertility in the United

States: An Ethics Committee opinion, Fertil Steril; 104:

1104–1110.

Fauziah Y., 2012. Obstetri Patologi untuk Mahasiswa

Kebidanan dan Keperawatan, Nuha

Medika.Yogyakarta

Harris, JA., Menke, MN., Jessica, KH., Moniz, MH.,

Perumalswami, CR., 2017. Geographic access to

assisted reproductive technology health care in the

United Syayes: Population-based cross -sectional

study, Fertil Steril ;107(.4):1023-1027.

Harzif, AK., Santawi, VPA., ,Wijaya, S., 2019.

Discrepancy in perception of infertility and attitude

towards treatment options :Indonesian urban and rural

area, BMC Reproductive Health;16:126.

HIFERI., 2013. Konsensus Penanganan Infertilitas,

Himpunan Endokrinologi Reproduksi dan Fertilitas

Indonesia. Jakarta, edisi 1.

Ho, JR., Hoffman, JR., Aghajanova, L., Smith, JF.,

Cardenas, M., Herndon, CN., 2017. Demographic

analysis of a low resource, socioculturally diverse

urban community presenting for infertility care in a

United States public hospital, Contraception and

Reproductive Medicine ;2(17):1-9.

Inhorn, MC., Patrizio, P., 2014. Infertility around the globe:

New thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and

global movements in the 21st century, Hum Reprod

Update; 21: 411–426.

Insogna, IG., Ginsburg, ES., 2018. Infertility, Inequality,

and How Lack of Insurance Coverage Compromises

Reproductive Autonomy, AMA Journal of Ethics.;

20(12):E1152-1159.

Irianto, K., 2014. Panduan Lengkap Biologi Reproduksi

Manusia Untuk Paramedis dan Nonmedis, Alfabeta.

Bandung.

Kaur, M., Meena, KK., Meena, KL., Singh, K., et al., 2018.

Burden of infertility and its associated factors: A cross

sectional descriptive analysis of infertility cases

reported at a tertiary level hospital of Rajasthan,

International Multispecialty Journal of Health

;4(4):144-149.

Klitzman, R., 2018. Gatekeepers for infertility treatment?

Views of ART providers concerning referrals by non-

ART providers, Reproductive BioMedicine and Society

Online;5:17–30.

Kunicki, M., Lukaszuk, K., Liss, J., Jakiel, G.,

Skowronska., 2018. Demographic characteristics and

AMH levels in rural and urban women participating in

an IVF programme, Annals of Agricultural and

Environmental Medicine ;25(1):120-123.

Roudsari RL., Allan HT., 2011. Women’s Experiences and

Preferences in Relation to Infertility Counselling: A

Multifaith Dialogue, Int J Fertil Steril; 5(3): 158-167

Lakatos, E., Szigeti, JF., Ujma, PP., Sexty, R., Balog P.,

2017. Anxiety and depression among infertile women:

a cross-sectional survey from Hungary, BMC Womens

Health.;17(1):48.

Maxwell, E., Mathews, M., Mulay, S., 2017. The Impact

of Access Barriers on Fertility Treatment Decision

Making: A Qualitative Study From the Perspectives of

Patients and Service Providers, J Obstet Gynaecol Can

;1-8.

Ombelet, W., 2011. Global access to infertility care in

developing countries: a case of human rights, equity

and social justice, Facts, views Vis ObGyn; 3: 257–66.

Omu, FE., Omu, AE., 2010. Emotional reaction to

diagnosis of infertility in Kuwait and succesful client’s

perception of nurse’ role during treatment, BMC

Nurs.;18(9):5.

Peterson, MM., 2005. Assisted reproductive technologies

and equity of access issues, J Med Ethics ; 31: 280–285.

Rooney, KL., Domar, AD., 2018. The relationship between

stress and infertility, Dialogues Clin Neurosci; 20: 41–

47.

Roupa Z; Polikandrioti M; Sotiropoulou P; Faros E;

Koulouri A; Wozniak G; Gourni M., 2009. Cause of

Infertility in Women at Reproductive Age, Health

Science Journal; 3(2): 1-8.

Sadeghi, MR., 2015. Access to infertility services in middle

east, J Reprod Infertil; 16: 179.

Thompson, C., 2006. God is in the details: Comparative

perspectives on the intertwining of religion and assisted

reproductive technologies, Cult Med Psychiatry; 30:

557–561.

Turnip, A., Andrian, Turnip, M., Dharma, A., Paninsari, D.,

Nababan, T., Ginting, C.N., 2020. An application of

modified filter algorithm fetal electrocardiogram

signals with various subjects, International Journal of

Artificial Intelligence, vol. 18, no., 2020.

Udgiri, R., Patil, VV., 2019. Comparative Study to

Determine the Prevalence and Socio-Cultural Practices

of Infertility in Rural and Urban Field Practice Area of

Tertiary Care Hospital, Vijayapura, Karnataka, Indian

J Community Med ; 44(2):129–133.

HIMBEP 2020 - International Conference on Health Informatics, Medical, Biological Engineering, and Pharmaceutical

156

Wijaya ,C., Andrian, M., Harahap, M., Turnip, A., 2019.

Abnormalities State Detection from P-Wave, QRS

Complex, and T-Wave in Noisy ECG, Journal of

Physics: Conference Series, Volume 1230, (2019)

012015. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1230/1/012015.

Distribution of stress level among infertility patients,

Middle East Fertility Society Journal; 22:145–148.

Wu, AK., Odisho, AY., Washington, SL., etal., 2014. Out-

of-pocket fertility patient expense: Data from a

multicenter prospective infertility cohort, J Urol;

191:427–432

Access Barriers of Infertility Services for Urban and Rural Patients

157