The Effect of Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) Leaf Ethanolic

Extract Gel on Superoxide Dismutase and Interleukin-1β Levels

in Wound Healing after Tooth Extraction in Diabetic Rats

Almasyifa Herlingga Rahmasari Amin¹

1

, Yusuf Asto Pamasja

12

,

Christiana Cahyani Prihastuti

23

, Haris Budi Widodo

24

, Hernayanti

35

¹ Dental Medicine Program, Faculty of Medicine, Jenderal Soedirman University, Purwokerto, Indonesia

2

Dental Medicine Program, Department of Oral Biology, Jenderal Soedirman University, Purwokerto, Indonesia

3

Department of Ecotoxicology, Faculty of Biology, Jenderal Soedirman University, Purwokerto, Indonesia

Keywords: Jackfruit, Diabetes Mellitus, Tooth Extraction, Superoxide Dismutase, IL-1β

Abstract: Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disease characterized by hyperglycemia, which can cause complications, such

as impaired wound healing after tooth extraction. The high level of blood glucose will increase ROS, leading

to the degradation of SOD and elevation of IL-1β. Jackfruit leaf contains flavonoids with antioxidant and anti-

inflammatory activities. This research aimed to study the effect of topical administration of jackfruit leaf

ethanolic extract gel (JLEEG) after tooth extraction on SOD and IL-1β in gingiva tissue near tooth socket in

diabetic rat models. The study was experimental laboratory research with a randomized posttest-only control

group design. Thirty-five male Wistar rats were used as the sample and divided into 5 groups: T1, T2, T3

(diabetic rat groups treated with JLEEG concentrations of 5%, 10%, and 15% respectively), C1 (healthy

control group), and C2 (negative control group). The treated groups showed higher SOD levels and lowered

IL-1β levels in comparison to the negative control group. Statistical analysis using One-Way ANOVA

indicated significant differences (p<0.01) between the treated groups and the negative control group. 15%

was considered the most effective concentration to reduce the inflammation phase and accelerate the healing

process of tooth extraction wounds in diabetic conditions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disease characterized

by hyperglycemia due to disturbances in insulin

secretion, insulin action, or even both

(American

Diabetes Association, 2013). Insulin is a hormone

produced by the pancreas to regulate glucose

metabolism, and when it does not work correctly,

hyperglycemia will occur and cause severe damage to

nerves and blood vessels (Afifah, 2016; World Health

Organization, 2016). The inhibition of oral wound

healing in diabetic patients is caused by leukocyte

dysfunction, increased blood viscosity, and thickened

blood vessel walls. These can result in

microcirculation and changes in the permeability of

1

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3200-4917

2

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8222-4574

3

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0611-7651

4

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7164-9841

5

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3468-7563

blood vessels, thus inhibiting wound healing (Kolluru

et al., 2012; Mozzati et al., 2014; Gould et al., 2015).

Tooth extraction can cause a wound around the

socket

(Pedersen, 1996). The acute wound healing

process in normal individuals can be completed

within three weeks with an inflammatory phase (1-4

days), a proliferative phase (4-21 days), and followed

by a remodeling phase until the following year

(Morison, 2011; Stacey, 2016). If the healing process

stops at one of these phases, the wound will become

chronic, which eventually extends the healing time

(Orsted et al., 2011).

The inflammatory phase involves various

proinflammatory agents, e.g., interleukin-1β (IL-1β),

which serves as the body's defense

(Seil et al., 2012).

Hyperglycemic conditions can stimulate

164

Rahmasari Amin, A., Pamasja, Y., Prihastuti, C., Widodo, H. and Hernayanti, .

The Effect of Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) Leaf Ethanolic Extract Gel on Superoxide Dismutase and Interleukin-1 Levels in Wound Healing after Tooth Extraction in Diabetic Rats.

DOI: 10.5220/0010489501640169

In Proceedings of the 1st Jenderal Soedirman International Medical Conference in conjunction with the 5th Annual Scientific Meeting (Temilnas) Consortium of Biomedical Science Indonesia

(JIMC 2020), pages 164-169

ISBN: 978-989-758-499-2

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

proinflammatory cytokine production by increasing

free radicals, therefore prolonging the inflammatory

phase and inhibiting the wound healing process

(Gonzalez et al., 2012). Previous research proved that

the inflammatory phase in rat models of diabetes

mellitus lasted longer, with proinflammatory

cytokine levels reaching their peaks on Day-5 and

starting to decrease on Day-10, rather than on Days

1-4 (Mirza et al., 2014).

An antioxidant enzyme can inhibit free radicals in

the body, namely Superoxide Dismutase (SOD). SOD

can prevent cell damage caused by oxidative stress

compounds, usually known as Reactive Oxygen

Species (ROS). In hyperglycemic conditions, the

forming of ROS can take 3-4 times faster than the

dismutation process by SOD, thus allowing SOD

levels to decrease. Consequently, additional

antioxidants from outside the body are needed in this

situation

(Mittal et al., 2014).

Flavonoids are known as one of the external

sources of antioxidants to reduce ROS. They can

neutralize free radicals and stimulate the production

of antioxidant enzymes in the body

(Panche et al.,

2016; Dewanto and Isnaeni, 2017). They can also act

as anti-inflammatory agents by inhibiting

inflammatory cytokines' production to accelerate the

wound healing process

(Leyva-López et al., 2016).

Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) leaf can be used

as a natural antioxidant and anti-inflammatory

because they contain flavonoids, saponins, and

tannins

(Hamzah et al., 2013; Asmaliani and Iwo,

2016)

A previous study showed that the treatment of

male albino rats with incision wounds in

subcutaneous skin tissue with 5% jackfruit leaf

methanolic extract ointment led to a significant

reduction in epithelialization period, an increase in

epithelialization process, and an acceleration in

wound contraction when compared to the control

group

(Gupta et al., 2009). Another study also

revealed that 5%, 10%, and 15% concentrations of

jackfruit leaf ethanolic extract ointment could

accelerate incision wounds' healing process in

subcutaneous skin of rabbit models

(Hamzah et al.,

2013).

Based on this background, the purpose of this

study was to compare the effects of 5%, 10%, and

15% concentrations of JLEEG on SOD and IL-1β

levels in wound healing after tooth extraction in

diabetic models of Wistar rats. Rats with diabetes

mellitus condition would be induced with

streptozotocin (Wang and Wang, 2017). The levels of

SOD and IL-1β in diabetic rats after tooth extraction

were measured in the inflammatory phase, on Day-6

after they were treated with the jackfruit leaf extract

for 5 days.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Medicine

Jenderal Soedirman University approved the content

and execution of this study with the letter

042/KEPK/II/2019 and 1009/KEPK/II/2019. The

study was experimental laboratory research with a

randomized posttest-only control group design. The

samples were 35 male Wistar rats, aged 2-3 months,

with a 200-250 bodyweight. The rats were divided

into 5 groups: three treated groups, namely T1, T2,

and T3 (diabetic rat groups treated with JLEEG

concentrations of 5%, 10%, and 15% respectively)

and two control groups, namely C1 (healthy control

group without diabetic condition) and C2 (negative

diabetic control group), both of which were treated

with 2% concentration of Na-CMC after tooth

extraction.

2.1 Jackfruit Leaf Ethanolic Extract

Gel Processing

2 grams of Na-CMC base gel was sprinkled over 100

ml of heated distilled water and waited at least 24

hours until the entire powder was dissolved to obtain

a concentration of 2% (w/v). 0.5 grams, 1 gram, and

1.5 grams of jackfruit leaf extract were then added to

9.5 ml of 2% Na-CMC solution to obtain a 10 ml gel

with different concentrations of 5%, 10%, and 15%

(w/v), respectively. Subsequently, the solution was

stirred until it was homogeneous and cooled down

until it turned into a gel

(Nofikasari et al., 2016).

2.2 Diabetic Rat Models

Rat models of diabetes mellitus were induced by the

injection of streptozotocin (STZ). STZ was injected

into fasting rats intraperitoneally with a concentration

of 2.5 ml (45 mg/kg BW) after being diluted in 0.05

M citrate buffer with 4.5 pH. Three days after the STZ

injection, the average blood glucose levels were 265

mg/dL (≥200 mg/dL) (Daniel et al., 2015).

2.3 Tooth Extraction and Treatment

Administration

Rats were injected with ketamine intraperitoneally at

a dose of 85 mg/kg BW. The mandibular left incisors

in rats were extracted. The treatment after tooth

The Effect of Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) Leaf Ethanolic Extract Gel on Superoxide Dismutase and Interleukin-1 Levels in Wound

Healing after Tooth Extraction in Diabetic Rats

165

extraction was given topically using a cotton swab for

five consecutive days. Na-CMC with a concentration

of 2% was given for the control groups (C1 and C2),

and JLEEG with different concentrations was given

for the treated groups (T1, T2, and T3).

2.4 Tissue Retrieval and Isolation

On Day-6, the rats were terminated using ether, and ±

25 mg gingival tissue near the tooth socket was taken.

The tissue sample was then frozen with liquid

nitrogen and mashed with a mortar and pestle. Every

5 mg of tissue was added with 1 ml of lysis buffer.

The tissue was smoothed, then the sonication was

performed (10

11

x 3 with 30-second intervals). The

tissue lysate was incubated for 45 minutes, then

centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 minutes. The

supernatant was separated from the pellets, put in a

new tube, and stored at -80

0

C.

2.5 Measurement of SOD and IL-1β

Levels

Each group's SOD enzyme levels were measured with

a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 505

nm and a temperature of 25

0

C.

The formula to calculate SOD levels applies as

follows:

sample absorbance

absorbance standard

30.65 U/ml

The IL-1β level of each group was measured using

the Rat IL-1β ELISA Elabscience® kit.

2.6 Statistical Data Analysis

The results were analyzed statistically for data

normality with Shapiro-Wilk and data homogeneity

with Levene's test. The data were then analyzed using

a parametric statistical test (One-Way ANOVA) and

Post Hoc analysis (Least Significant Difference) to

figure out the significant differences between the

groups with a confidence level of 95% (p<0.05) or

99% (p<0.01).

3 RESULTS

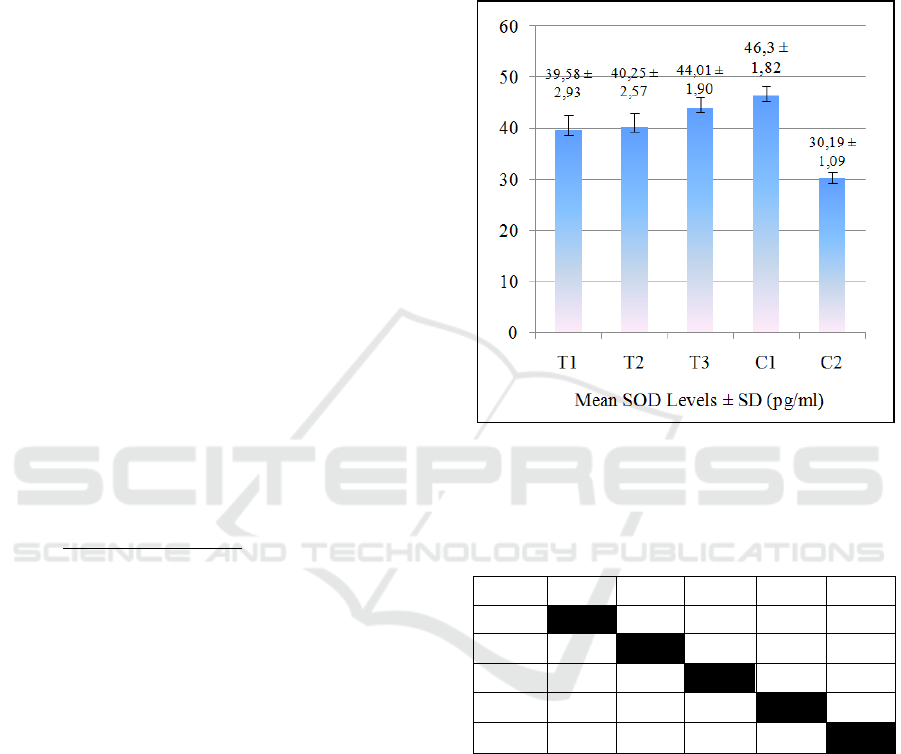

The results of the mean SOD levels of all groups are

provided in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows that in the

treated groups, SOD levels increased over JLEEG

concentrations. The lowest SOD level was in the

negative control group (C2), while the highest SOD

level in the healthy control group (C1). The One-way

ANOVA hypothesis test showed p-value = 0.000

(p<0.01). This result means that there was a very

significant effect of JLEEG concentration on the SOD

level. The data was then tested on Post Hoc LSD, and

the results are given in Table 1.

Figure 1: The mean ± Standard Deviation of SOD Levels.

T1= 5% JLEEG treated group; T2=10% JLEEG treated

group; T3= 15% JLEEG treated group; C1= healthy control

group; C2= negative control group.

Table 1: Results of Post-Hoc LSD test on SOD Levels.

Group T1 T2 T3 C1 C2

T1 0.565

0.001

**

0.000

**

0.000

**

T2 0.565 0.003

**

0.000

**

0.000

**

T3 0.001

**

0.003

**

0.056 0.000

**

C1 0.000

**

0.000

**

0.056

0.000

**

C2 0.000

**

0.000

**

0.000

**

0.000

**

Note: T1= 5% JLEEG treated group; T2=10% JLEEG

treated group; T3= 15% JLEEG treated group; C1= healthy

control group; C2= negative control group.

*

= a significant difference (p<0.05)

**

= a very significant difference (p<0.01)

The results of the Post-Hoc LSD test revealed that

there was a very significant difference between the

treated groups (T1, T2, and T3) and the negative

control group (C2) (p≤0.01). However, there was no

significant difference between T3 and C1 in SOD

levels (p>0.05). The results of the mean IL-1β levels

of the groups are presented in Figure 2.

JIMC 2020 - 1’s t Jenderal Soedirman International Medical Conference (JIMC) in conjunction with the Annual Scientific Meeting

(Temilnas) Consortium of Biomedical Science Indonesia (KIBI )

166

Figure 2: The mean ± Standard Deviation of IL-1β Levels.

T1= 5% JLEEG treated group; T2= 10% JLEEG treated

group; T3= 15% JLEEG treated group; C1= healthy control

group; C2= negative control group.

Table 2: Results of Post Hoc LSD test on IL-1β levels.

Group T1 T2 T3 C1 C2

T1 0.049

*

0.001

**

0.000

**

0.000

**

T2 0.049

**

0.115 0.002

**

0.000

**

T3 0.001

**

0.115 0.102 0.000

**

C1 0.000

**

0.002

**

0.102

0.000

**

C2 0.000

**

0.000

**

0.000

**

0.000

**

Figure 2 shows that the higher the JLEEG

concentrations in the treated groups, the lower the IL-

1β levels. The highest IL-1β level appeared in the

negative control group (C2), while the lowest in the

healthy control group (C1). The One-way ANOVA

test results indicated the value of p = 0.000 (p<0.01).

This result means that there was a very significant

effect of JLEEG concentration on IL-1β level. The

data was then tested on Post Hoc LSD, and the results

are given in Table 2.

The results of the LSD Post Hoc test indicated that

there was a very significant difference between the

treated groups. In addition, there was no significant

difference between T3 and C1 in terms of IL-1β

levels.

4 DISCUSSION

The SOD levels of the diabetic rats in the negative

control group (C2) were lower than those of the

healthy control group (C1), while the IL-1β levels of

C2 were higher than those of C1. This result means

that diabetes mellitus in rats affects both SOD and IL-

1β levels after tooth extraction.

An excessive amount of ROS resulting from the

condition of diabetes mellitus will decrease the

antioxidant levels of the body, i.e., superoxide

dismutase (SOD). The amount of antioxidant

enzymes is lower in pancreatic beta cells than in any

other organs with only a limited amount of SOD,

making it more sensitive to ROS's attack. This

condition will drastically reduce SOD levels in

wounded diabetic rats

21

. On the other hand, a high

amount of ROS can lead to the accumulation of

advanced glycosylation products (AGEs), which will

bind to the receptor for AGE (RAGE), thereby

activating NF-κB and stimulating proinflammatory

cytokines such as IL-1β. An enormous amount of

ROS will enable IL-1β to be secreted in high levels,

thus prolonging the inflammation time (Graves and

Kayal, 2008; Shita, 2015).

The results showed a significant effect of JLEEG

administration on post-tooth extraction wounds in the

treated groups with 5%, 10%, and 15% JLEEG

compared to the negative control group. The SOD

levels were higher in the treated groups, while the IL-

1β levels were lower than the negative control group.

This condition can be affected by flavonoid content

in jackfruit leaf extract known to have anti-

inflammatory abilities to accelerate the wound

healing process by suppressing excessive

inflammatory mediator activity

(Asmaliani and Iwo,

2016). According to previous studies, there was an

increase in SOD activity in diabetic rats after they

were given ginger extract and cardamom leaf. There

was a decrease in the IL-1β levels of diabetic rats after

they were administered with Moringa oleifera

extract, known to contain flavonoids (Morakinyo et

al., 2011; Sari et al., 2014; Muhammad et al., 2016).

The content of flavonoids in jackfruit leaf also

plays a vital role as an antioxidant agent by increasing

SOD levels. Research with plant extracts containing

flavonoids has been proven to increase the SOD

activity of the wounded diabetic rats because they are

associated with reducing lipid peroxidation and

ROS's decrease, e.g., superoxide anion (Rahmawati et

al., 2014). Furthermore, jackfruit leaf also contains

Cu and Zn, which can function as SOD cofactors to

form Cu, Zn-SOD and increase SOD levels in the

body. A high amount of SOD can suppress

The Effect of Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) Leaf Ethanolic Extract Gel on Superoxide Dismutase and Interleukin-1 Levels in Wound

Healing after Tooth Extraction in Diabetic Rats

167

superoxide anion in a diabetic rat, thereby

accelerating the healing process by reducing the

inflammatory period (Fattah et al., 2012; Sun et al.,

2015).

Moreover, flavonoids can serve as extreme metal

chelating (Fe2 + and Cu2 +), so free radicals are not

formed through the Fenton reaction, and the

proinflammatory cytokines decrease (Birben et al.,

2012). The existence of saponins in jackfruit leaf can

reduce blood glucose by increasing the small

intestine's permeability and increase substance uptake

to inhibit the absorption of smaller substance

molecules that should be absorbed more quickly, i.e.,

glucose (Fiana and Oktaria, 2016).

Flavonoids can prevent ROS formation by

donating H

+

atoms, allowing them to become neutral

and their levels to decrease. The decreased levels of

ROS will affect the transcription factor of NF-κB, so

there will be a decrease in the production of IL-1β.

The decreasing levels of IL-1β can affect the

phospholipase A2 enzyme in degrading the

phospholipid enzyme, which can prevent the

production of arachidonic acid from being excessive.

A decrease in arachidonic acid itself can reduce the

production of prostaglandin-2 (PGE-2) through the

cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) pathway. A small

amount of PGE-2, which acts as an inflammatory

mediator, will reduce inflammatory responses to

vasodilation, edema, and pain, allowing the wound

healing process to run normally (Panche et al., 2016;

Leyva-López et al., 2016).

This study indicated that the increased

concentrations of JLEEG could decrease IL-1β levels

and increase SOD levels in the treated groups. The

post-hoc LSD test results also revealed that the

administration of JLEEG with a concentration of 15%

to the diabetic rats with tooth extraction wounds

could increase SOD levels and reduce IL-1β levels

closer to healthy rats without diabetes mellitus. This

result implies that the inflammatory process in this

group decreased and continued to the proliferation

phase. Therefore, the topical administration of

JLEEG at 15% is considered the most effective

compared to the lower concentrations to enhance the

wound healing process after tooth extraction in

diabetic conditions.

The results of this study indicated a potential role

of the jackfruit leaf ethanolic extract topical gel as an

adjuvant treatment to enhance the wound healing

process after tooth extraction in diabetic patients.

Advanced research is needed to determine the optimal

dose and lethal dose of the ethanol extract of jackfruit

leaf.

5 CONCLUSION

The administration of jackfruit leaf ethanolic extract

gel increases the SOD level. It decreases IL-1β level

on post-extraction tooth socket tissue in diabetes

mellitus rat models, suggesting the acceleration of the

healing process after tooth extraction. The 15% gel

concentration is considered the most effective

compared to 5% and 10% gel concentrations.

REFERENCES

American Diabetes Association, 2013. Standards of

medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes

care, 36(Supplement 1), pp.S11-S66.

Afifah, H.N., 2016. Mengenal Jenis-Jenis Insulin Terbaru

untuk Pengobatan Diabetes. Majalah

Farmasetika, 1(4), pp.1-4.

World Health Organization, 2016. Global report on

diabetes. WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication

Data. World Health Organization.

Kolluru, G.K., Bir, S.C. and Kevil, C.G., 2012. Endothelial

dysfunction and diabetes: effects on angiogenesis,

vascular remodeling, and wound healing. International

Journal of Vascular Medicine, 2012.

Mozzati, M., Gallesio, G., di Romana, S., Bergamasco, L.

and Pol, R., 2014. Efficacy of plasma-rich growth factor

in the healing of postextraction sockets in patients

affected by insulin-dependent diabetes

mellitus. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial

Surgery, 72(3), pp.456-462.

Gould, L., Abadir, P., Brem, H., Carter, M., Conner‐Kerr,

T., Davidson, J., DiPietro, L., Falanga, V., Fife, C.,

Gardner, S. and Grice, E., 2015. Chronic wound repair

and healing in older adults: current status and future

research. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 23(1), pp.1-

13.

Pedersen, G.W., 1996. Buku Ajar Praktis Bedah Mulut,

terj. EGC, Jakarta.

Morison, M. J. 2011. Manajemen Luka. EGC, Jakarta

Stacey, M. 2016. Why Does Wound Heal? Wounds

International, 7(1), pp.16-21.

Orsted, H.L., Keast, D., Forest-Lalande, L. and Megie,

M.F., 2011. Basic principles of wound healing. Wound

Care Canada, 9(2), pp.4-12.

Seil, M., Ouaaliti, M.E., Abdou Foumekoye, S., Pochet, S.

and Dehaye, J.P., 2012. Distinct regulation by

lipopolysaccharides of the expression of interleukin-1β

by murine macrophages and salivary glands. Innate

Immunity, 18(1), pp.14-24.

Gonzalez, Y., Herrera, M.T., Soldevila, G., Garcia-Garcia,

L., Fabián, G., Pérez-Armendariz, E.M., Bobadilla, K.,

Guzmán-Beltrán, S., Sada, E. and Torres, M., 2012.

High glucose concentrations induce TNF-α production

through the down-regulation of CD33 in primary

human monocytes. BMC immunology, 13(1), p.19.

JIMC 2020 - 1’s t Jenderal Soedirman International Medical Conference (JIMC) in conjunction with the Annual Scientific Meeting

(Temilnas) Consortium of Biomedical Science Indonesia (KIBI )

168

Mirza, R.E., Fang, M.M., Weinheimer-Haus, E.M., Ennis,

W.J. and Koh, T.J., 2014. Sustained inflammasome

activity in macrophages impairs wound healing in type

2 diabetic humans and mice. Diabetes, 63(3), pp.1103-

1114.

Mittal, M., Siddiqui, M.R., Tran, K., Reddy, S.P. and

Malik, A.B., 2014. Reactive oxygen species in

inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxidants & redox

signaling, 20(7), pp.1126-1167.

Panche, A.N., Diwan, A.D. and Chandra, S.R., 2016.

Flavonoids: an overview. Journal of nutritional

science, 5.

Dewanto, H.N. and Isnaeni, W., 2017. Pengaruh Ekstrak

Kulit Buah Rambutan terhadap Kualitas Sperma Tikus

yang Terpapar Asap Rokok. Life Science, 6(2), pp.62-

68.

Leyva-López, N., Gutierrez-Grijalva, E.P., Ambriz-Perez,

D.L. and Heredia, J.B., 2016. Flavonoids as cytokine

modulators: a possible therapy for inflammation-related

diseases. International journal of molecular

sciences, 17(6), p.921.

Asmaliani, I., Iwo, M. I. 2016. Uji Aktivitas Antiinflamasi

dari Ekstrak Metanol Daun Nangka terhadap Tikus

yang Diinduksi Karagenan. As-Syifaa Jurnal

Farmasi, 8(2), pp.28-32.

Hamzah, H., Fatimawali, F., Yamlean, P.V. and Mongi, J.,

2013. Formulasi salep ekstrak etanol daun nangka

(Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.) dan uji efektivitas

terhadap penyembuhan luka terbuka pada

kelinci. PHARMACON, 2(3).

20. Gupta, N., Jain, U.K. and Pathak, A.K., 2009. Wound

healing properties of Artocarpus heterophyllus

Lam. Ancient science of life, 28(4), p.36.

Wang, J. and Wang, H., 2017. Oxidative stress in pancreatic

beta cell regeneration. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular

Longevity, 2017.

Nofikasari, I., Rufaida, A., Aqmarina, C.D., Failasofia, F.,

Fauzia, A.R. and Handajani, J., 2016. Efek aplikasi

topikal gel ekstrak pandan wangi terhadap

penyembuhan luka gingiva. Majalah Kedokteran Gigi

Indonesia, 2(2), pp.53-59.

Daniel, E.E., Mohammed, A., Tanko, Y., Ahmed, A.,

Adams, M.D. and Atsukwei, D., 2015. Effects of

lycopene on thyroid profile in streptozotocin-induced

diabetic wistar rats. European Journal of

Biotechnology and Bioscience, 3(1), pp.21-28.

Shita, A. D. P. 2015. Perubahan Level TNF-A dan IL-1

pada Kondisi Diabetes Melitus. Proceeding of

Dentistry Scientific Meeting II. I-V:1-7.

Graves, D.T. and Kayal, R.A., 2008. Diabetic

complications and dysregulated innate

immunity. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and

virtual library, 13, p.1227.

Morakinyo, A.O., Akindele, A.J. and Ahmed, Z., 2011.

Modulation of antioxidant enzymes and inflammatory

cytokines: possible mechanism of anti-diabetic effect of

ginger extracts. African Journal of Biomedical

Research, 14(3), pp.195-202.

Sari, P.E., Simanjuntak, S.B.I. and Winarsi, H., 2014.

Aktivitas Enzim Superoksida Dismutase Tikus

Diabetes yang Diberi Ekstrak Daun Kapulaga

Amomum Cardamomum. Scripta Biologica, 1(3),

pp.196-196.

Muhammad, A.A., Arulselvan, P., Cheah, P.S., Abas, F.

and Fakurazi, S., 2016. Evaluation of wound healing

properties of bioactive aqueous fraction from Moringa

oleifera Lam on experimentally induced diabetic

animal model. Drug design, development and

therapy, 10, p.1715.

Rahmawati, G., Rachmawati, F.N. and Winarsi, H., 2014.

Aktivitas superoksida dismutase tikus diabetes yang

diberi ekstrak batang kapulaga dan

glibenklamid. Scripta Biologica, 1(3), pp.197-201.

Sun, Y., Yang, J., Wang, H., Zu, C., Tan, L. and Wu, G.,

2015. Standardization of leaf sampling technique in

jackfruit nutrient status diagnosis. Agricultural

Sciences, 6(02), p.232.

Fattah, M., Anggraeni, S.R., Alfian, S.D., Levita, J. and

Diantini, A., 2012. Stabilitas Sampel SOD-Eritrosit dan

GPx-Blood dalam Masa Penyimpanan Tujuh

Hari. Indonesian Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 1(4),

pp.162-170.

Birben, E., Sahiner, U.M., Sackesen, C., Erzurum, S. and

Kalayci, O., 2012. Oxidative stress and antioxidant

defense. World Allergy Organization Journal, 5(1),

pp.9-19.

Fiana, N. and Oktaria, D., 2016. Pengaruh kandungan

saponin dalam daging buah mahkota dewa (Phaleria

macrocarpa) terhadap penurunan kadar glukosa

darah. Jurnal Majority, 5(4), pp.128-132.

The Effect of Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) Leaf Ethanolic Extract Gel on Superoxide Dismutase and Interleukin-1 Levels in Wound

Healing after Tooth Extraction in Diabetic Rats

169