Building Competitive Advantage from Ubuntu: An African

Information Security Awareness Model

Tapiwa Gundu and Nthabiseng Modiba

Department of Computer Science and IT, Sol Plaatje University, Kimberley, South Africa

Keywords: Information Security Awareness, Information Security Compliance, Information Security Culture,

The Human Element, Ubuntu Philosophy.

Abstract: Research shows an increase in information security threats originating from the human element. These threats

are being aggravated by organizations continuing to only invest in technical controls like antivirus and firewall

technologies to guard cyber assets. However, a well-planned information security awareness campaign can

potentially alter the employees’ behaviour towards security. The body of knowledge is continuously growing

within the information security space, yet it seems that there is a lack of supporting theories or models for the

African context. This paper argues that African information security awareness and compliance initiatives can

only be addressed effectively by the consideration that an African employee is not a solitary agent but actually a

member of the wider community. The purpose of this study is to propose and validate a model for information

security awareness and compliance that builds its competitive advantage from the Ubuntu philosophy.

1 INTRODUCTION

African organizations often under estimate the need

to implement information security programs because

they consider themselves off the target of threat

actors. This might be a dangerous, misleading

misconception as sophisticated adversaries are

beginning to target naïve employees from these

African organizations as a means of gaining access

into the interconnected business ecosystems which

comprise of other organizations including

multinational in partnerships or subcontracting the

African organizations. This dangerous reality is made

worse by the fact that partnering organizations often

carry out minimum security background checks and

also carry out little or no security monitoring of their

partners, subcontractors and their supply chains.

Security breaches from naïve employees often

cause downtime which leads to lost productivity, direct

and indirect monetary losses, personal or sensitive

corporate information disclosure, and damage to the

organization’s goodwill (Steele & Wargo, 2007).

To mitigate this problem, organisations must first

understand how to reach all employees and make

them information security conscious. We believe that

when nurturing such consciousness on an African

context, the concept of Ubuntu should be taken into

consideration. Ifinedo (2014) and Tamjidyamcholo et

al. (2014) highlight the presence of a strong and

positive relationship between the awareness of

information security and the expectations of reducing

the risk behavior of information security. The biggest

advantage being where Ubuntu exists, there is already

a culture of adult education and mutual support

amongst the employees.

The remainder of the paper is structured as

follows; a review of literature and concepts,

discussion of the underpinning theoretical

framework, presentation of the proposed model,

discussion of the study’s methodology, discussions

on empirical work and findings, recommendations

and lastly, the conclusion.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Moorman and Blakely (1995) view individualism and

collectivism as ways to differentiate between

employees who are oriented towards self-interest and

value achieving own goals versus employees who are

orientated towards a collective social system than

self. A collectivistic employee gives group interests

priority over their own and seriously values belonging

to a group and will take care of the well-being of the

group even at the expense of their own personal

interests (Gundu, Maronga, & Boucher, 2019).

Gundu, T. and Modiba, N.

Building Competitive Advantage from Ubuntu: An African Information Security Awareness Model.

DOI: 10.5220/0008983305690576

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2020), pages 569-576

ISBN: 978-989-758-399-5; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

569

Collectivism in Africa was birthed by the hostile

environment the early people were subjected to. It

was only by community solidarity that they could

survive hunger, poverty, deprivation, isolation and

other challenges. Collectivism in Africa is known as

Ubuntu. Nelson Mandela, former (late) president of

South Africa and noble prize winner, regards the

Ubuntu philosophy as one that constitutes a way of

life with universal truths that strengthen an open

community (Renaud, Flowerday, Othmane, &

Volkamer, 2015).

2.1 The Ubuntu Philosophy

Ubuntu is a word derived from isiZulu (South African

language). It is usually identified by the aphorism

Umuntu Ngumuntu Ngabantu, which directly

translates to “a person is a person because of or

through others” (Tutu, 2004; Fraser-Moleketi, 2009).

Almost all African parts of the Bantu tribe have some

kind of the Ubuntu philosophy application integrated

into nearly all everyday life aspects (Rwelamila,

Talukhaba and Ngowi, 1999). Ubuntu is referred to,

in other African countries as: unhu in Zimbabwe,

umundu in Kenya, bumuntu in Tanzania, vumuntu in

Mozambique, and gimuntu in the Congo. In

Zimbabwe, as in other African countries, the Zulu

aphorism is also available in Shona: munhu, munhu

nekuda kwevanhu. “None of us comes into the world

fully formed. We would not know how to think, or

walk or speak, or behave as human beings unless we

learnt it from other human beings. We need other

human beings in order to be human” (Tutu, 2004).

In the western ideologies, identity and solidarity

are conceptually separable, that is one can exist

without any dependence or connection to the others,

however, Ubuntu views the two as inseparable

(Dearden & Miller, 2006). Solidarity creates a union

of interests and purposes among members of an

organization. Identity and solidarity ensures that

people will take ownership of the organization, which

means they begin to be protective because of the

realization that an injury to one is an injury to all. This

is what makes Ubuntu the perfect driver for

information security awareness.

2.1.1 Challenges Faced When using the

African Ubuntu Philosophy

1. Ubuntu philosophy is based on practice that was

not formally recorded.

The major challenge is indigenous African

knowledge not documented, it is mostly passed from

one generation to the next through word of mouth

(Afro-centric Alliance, 2001). Ancient Africans did

not have a writing culture like their eastern and the

western ideological counterparts.

2. Ubuntu philosophy is wrongly associated with

some obsolete African traditional rituals,

practices and customs.

Some African traditions are no longer useful in the

modern world, although they may still persist in a few

communities. These practices, such as witchcraft, are

linked confusedly with Ubuntu.

3. The proliferation of foreign ideologies challenges

the African Ubuntu philosophy.

In a world with multi-cultures, it is therefore difficult

for an African Ubuntu philosophy which is not

properly recorded to be posed with other foreign

philosophies that were properly documented and have

already penetrated majority of societies.

2.2 Information Security Awareness

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

research report of 2014 supports the view that the

growth in the use of cyberspace in Africa is not

matched by the necessary skills to utilize it securely.

Information security awareness campaign initiatives

are classified into awareness and training. Awareness

is meant to raise general awareness why security is

important and the security controls in place, while

training facilitates a more in-depth level of user

understanding as well as how to act securely while

working with organizational computer systems (Chua,

Wong, Low, & Chang, 2018; Gundu, 2019b; Herath &

Rao, 2009; Russell, 2002; Talaei-Khoei, Solvoll, Ray,

& Parameshwaran, 2012). Effective information

security awareness and training programs aim at

explaining the expected behaviors for working with

computer systems within the organization (Chua et al.,

2018; Gundu & Maronga, 2019; Herath & Rao, 2009;

Safa et al., 2015; Talaei-Khoei et al., 2012). The

absence of awareness programs may be an indication

of a critical gap in effective security implementation

(Bauer, Bernroider, & Chudzikowski, 2017; Ifinedo,

2014) as these are a vital component of an effective

information security strategy which may help

minimize potential damage caused by naive employees

(Allam, Flowerday, & Flowerday, 2014; Alshboul &

Streff, 2017; Gundu, 2019).

In summary, the purpose of security awareness

efforts is to change behavior and reinforce compliance

(Chua et al., 2018; McCormac et al., 2018; Shaw,

Chen, Harris, & Huang, 2009). A properly structured

information security awareness program may

ultimately improve an organization’s efficiency.

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

570

The effectiveness of security awareness drives in

Africa remain very unclear as some employees,

regardless of their knowledge, do not fully comply

with their organization’s security policies (knowing

and doing gap) (Siponen, Mahmood and Pahnila,

2014; Shropshire, Warkentin and Sharma, 2015).

This study argues that this may be attributed to

applying individualistic security initiatives on a

collectivism society based workforce.

3 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Numerous studies have verified the theory of planned

behavior (TPB) empirically in the fields of

psychology, management, medicine, environmental

science, and information systems. The TPB views

employee behavior as driven by their behavioral

intentions which are formulated by the employee's

attitude, the subjective norms, and the employee's

perception of the ease with which the behavior may

be performed (Ajzen, 2011).

4 MODEL FOR AFRICAN

INFORMATION SECURITY

AWARENESS AND

COMPLIANCE

Information security awareness and training

approaches are based on persuasive communication

which requires the employee to buy into the idea for

them to behave securely.

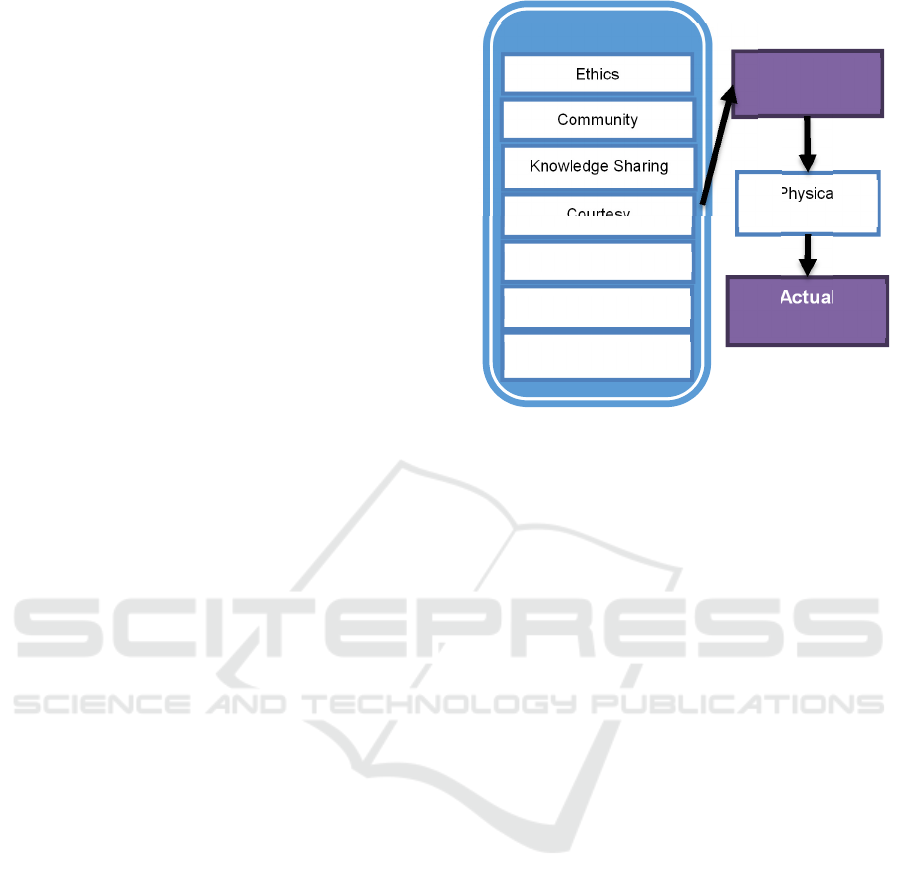

The approaches used for addressing information

security awareness and training initiatives within

collectivist and individualism communities are

different, therefore organizations should factor in

those differences to have effective controls. Figure 1

depicts the proposed model for African information

security awareness and compliance which builds

from advantages of the African collectivist Ubuntu

philosophy.

This proposed model is in agreement with the

TPB that suggests that employee behaviours are pre-

planned or reasoned as needed.

Western companies wishing to do business on

African ground or those employing personnel from

Africa should also consider training their employees

under the umbrella of the Ubuntu philosophy because

doing so can help to cultivate compliance.

Figure 1: An African information security awareness and

compliance model.

4.1 Constructs

This section discusses how the constructs of the

model were coined through literature reviews as well

as the two researchers’ personal knowledge and

experiences from their over 30 years of African

(South Africa and Zimbabwe) upbringing and

associations.

1. The individual is less important than the

community under the Ubuntu philosophy.

In Africa, the definition of an individual is community-

based (N. A. Gianan, 2010; Rwelamila et al., 1999) and

not individualist which is why people identify

themselves with clan names and not surnames or first

names, which is contrary to Western ideologies.

Competitive Advantage: If the information

security initiatives are well understood, employees

will help each other collectively to make sure they

have a secure environment.

2. Positive behavior is related to the Ubuntu

philosophy.

Sharing, kindness, love and sympathy are the main

human values emphasized by behavior in the Ubuntu

philosophy (Chitumba, 2013; Mangaliso, Mangaliso,

Knipes, Jean-Denis, & Ndanga, 2018; Rwelamila et

al., 1999). Respect is referred to as an objective and

neutral consideration of another employee’s beliefs,

property and values (Renaud et al., 2015; Tutu, 2004).

Competitive Advantage: Ubuntu will make people

behave positively because Ubuntu believes in being

ethical and acting considerately at all times. Ubuntu

considers it unethical to breach security.

Behavioural

Intention

Knowledge Sharing

Community

Courtesy

Team Spirit

Ethics

Ubuntu

Respect

Socio-cultural Values

Actual

Behaviour

Physical

Capability

Building Competitive Advantage from Ubuntu: An African Information Security Awareness Model

571

3. Sharing is related to the Ubuntu philosophy.

The Ubuntu philosophy believes one’s good fortune

can only be increased by sharing with people in their

society (N. Gianan, 2011; N. A. Gianan, 2010;

Muwanga-Zake, 2009). This subsequently also

enhances their status within the local communities.

Competitive Advantage: This means that if the

information security initiatives are bought in by a few

respected individuals within the Ubuntu hierarchy,

the knowledge will be infiltrated to all the employees

by means of the Ubuntu ‘sharing is caring’ concept.

This issue of community consciousness, which values

equitable allocation and sharing of wealth, knowledge

and responsibilities is considered the most strategic

advantage in this study.

4. Courtesy is an element of the Ubuntu philosophy.

The courteous behaviors of the Ubuntu philosophy

include even extending hospitality to total strangers

(Broodryk, 2005).

Competitive Advantage: Courtesy of Ubuntu can

help organizations by means of employees

courteously helping each other on how to act securely

while handling organizational information assets.

5. Ubuntu philosophy cultivates a team spirit

towards work.

Ubuntu views successes and failures as caused by

teamwork (Khomba & Kangaude-Ulaya, 2013). For

example, if an employee is given a good offer such as

a promotion, he/she may seek advice from the other

team players and elders before deciding. Sometimes

the employees even turn down such offers for the fear

of related social consequences.

Competitive Advantage: By default, Africans are

team players hence anything that needs to be worked

on as a team will almost always succeed.

6. Employees’ sociocultural values are recognized

by Ubuntu philosophy.

Employees in Africa have values that emanate from

socio-cultural underpinnings. It is also important to

understand the existence of extended family systems

of African employees that they expect to be respected

(Broodryk, 2005). In terms of the workplace,

employees view themselves as members of one

extended family as well.

Competitive Advantage: An organization’s

recognition that an African is part of an extended

family will make the employee feel understood and

respected and will influence the employee’s attitude

to the organization, which will also have an effect on

information security attitudes.

7. One should show respect to elders under the

Ubuntu philosophy.

Contrary to usual organizational culture were authority

flows from top management to general stuff, in the

African culture, it flows with age hierarchy from the

old to the young. This shows the importance of respect

for the elderly in the society which also applies in

corporate relationships (Mangaliso et al., 2018). With

this setup, an older employee is automatically expected

to be more superior than the younger ones, regardless

of education, rank or title. In an African context, it is

very awkward for older employees to be instructed by

the young.

Competitive Advantage: Any information security

initiatives will be more effective if well respectable

elders, according to the Ubuntu hierarchy, are made

to run with it as leaders. They are more likely to have

an impact as compared to a younger folk, even if they

are more experienced than the older one.

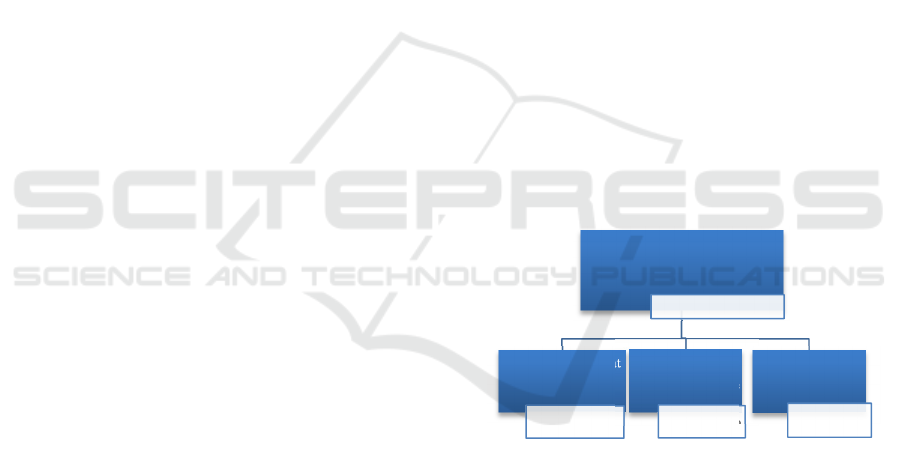

5 METHODOLOGY

An action research approach with mixed methods was

adopted for this study. The approach used in this study

was based on inductive reasoning. In other words, the

researcher formulated the research questions and then

conducted surveys from which general conclusions

were drawn based on the employee awareness trends

identified. The research methodology of this study can

be summarised by Figure 2.

Figure 2: Research methodology overview.

5.1 Research Method

Although this study primarily adopted an

interpretivist approach, quantitative data collection

and data analysis was also used in parallel (mixed

methods). The quantitative approach was to control

while qualitative research focused on description,

analysis and interpretation.

5.2 Research Design

This research took the design of a canonical action

research based on Davison, Martinsons and Kock

(2004) in which the researchers intervene from the

Model For African

Information Security

Awareness And Compliance

Outcome

Revealed factors that

influence African

security behaviour

Inductive

Literaure Study

Used to refine and

validate

practicability of the

model

Action Research

Used Theory of

Planned Behaviour

as backbone

Theoretical

Framework

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

572

perspective of an outsider. This canonical action

research was conducted at an organisation in South

Africa. The organisation employs 57 employees

however only 31 consented to participate in this study.

Data Collection

This study collected both primary and secondary data.

Secondary data was mostly obtained from websites,

published and white papers. The researchers

attempted to make sure most content of the content in

this study was current as these sources formed the

foundation of the study.

The collection of primary data was done in two

iterations by using online questionnaire/survey tests.

The data from the online surveys was used to assess

behavioural intentions, which were believed to be

highly influential to the carrying out of actual

behaviours.

6 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

The initial plan for this research was just to raise

information security awareness for the employees of

an organization with the hope of cultivating positive

behaviours, meaning it was just going to be one cycle.

However, we had encouraged the organisation to

repeat the campaigns at least once a year for the

benefit of new employees, refresher for the old and to

address new security issues that would have risen

within the months. However, after the first awareness

campaign we noticed that there was still need for

intervention sooner than we had anticipated because

employees did not change their behaviour as much as

we expected. We then did a thorough introspection of

our awareness and training initiatives, which led to

the suspicion that our efforts might have been

weakened by the adaptation of Western philosophies

in actioning these initiatives. Consequently, to

prove/disapprove this suspicion, another iteration was

conducted four months after the first. The difference

being the second iteration was based on the African

Ubuntu philosophy.

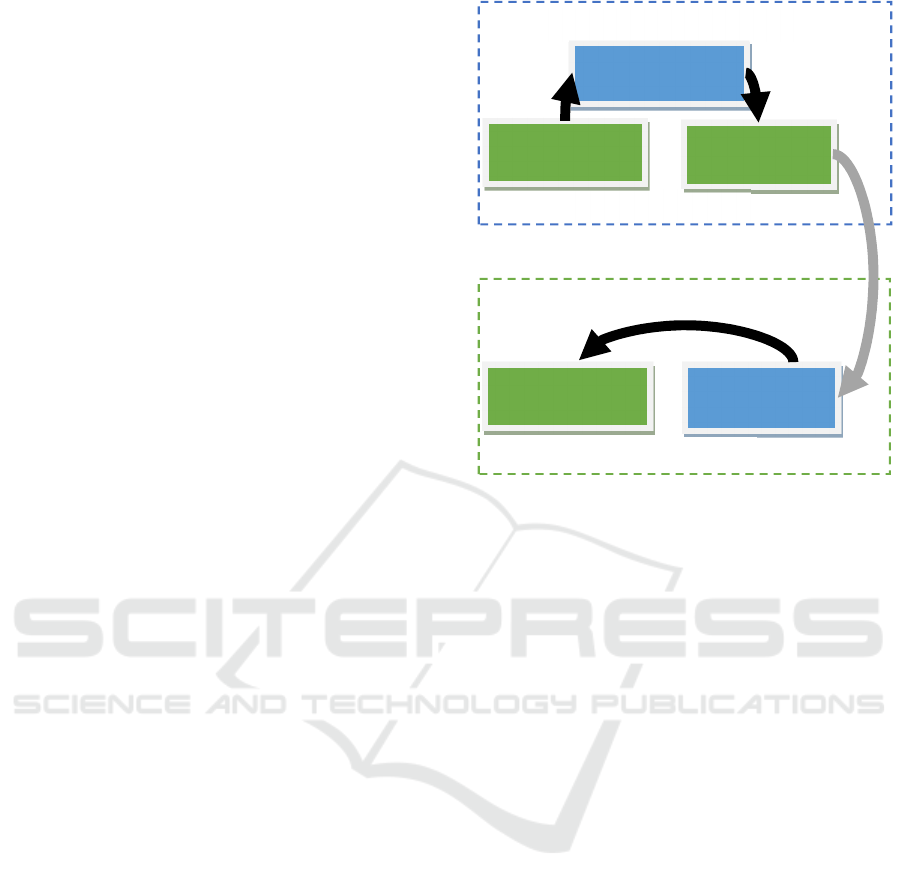

Iteration 1

Most organizations use the traditional classroom style

for awareness and training. However, for the first

iteration, this study made use of the now widely used

e-learning method of information dissemination.

Studies show there is no significant difference in

either the short or long-term retention of knowledge

between people who learn in the traditional classroom

style or those using a computer (Sherif, Furnell, &

Clarke, 2015).

During this iteration, employees were viewed as

independent

individuals (Western Philosophy) all

Figure 3: Action research iterations/cycles.

working towards achieving their personal goals,

which when combined would achieve the

organizational goals. We considered each employee

to be acting on his or her own, making their own

choices.

The first activity of this iteration was assessing the

information security awareness levels before any

campaigns and training. This was done to measure the

initial levels as well as to identify information

security knowledge gaps that exist which were to be

addressed by the preceding awareness campaign. For

this assessment the Kruger and Kearney (2005)

awareness assessment tool was used. This tool

assesses the knowledge, attitude and behavioral

intent. The tool suggests that these three are

responsible for shaping actual behavior. The

assessment was through an online questionnaire/test

that asked questions gauging the employees’

information security knowledge, their attitude and

their intents.

The second activity was an awareness campaign.

All the participating employees were given a link to a

website that had information security campaign

material which they had to go through at their own

pace. However, because we knew some people would

not open the link or quickly browse through without

reading, we recorded every time they would login and

the time they spent on each lesson. The topics covered

in this campaign included: passwords, antivirus,

firewalls, malware, phishing, encryption and safety

on social media.

Awareness and

training

Awareness

assessment

Awareness

and training

Awareness

assessment

Iteration 1

Iteration 2

Western Philosophy Used

African Philosophy Used

Awareness

assessment

Building Competitive Advantage from Ubuntu: An African Information Security Awareness Model

573

The third activity was re-assessing the

information security awareness levels to see if it had

improved. This assessment was also done using

Kruger and Kearney's (2005) assessment tool. The

findings of this iterations revealed that the

employees’ information security awareness levels

were very low to start with; the overall score was

53%. However, it is evident that the awareness made

an impact as the new assessment score after the

campaign rose to 70%. This score, however, was not

satisfactory enough to conclude that the organization

was in safe hands. For both assessments 30 questions

were asked – 10 to identify the attitudes, 10 the intents

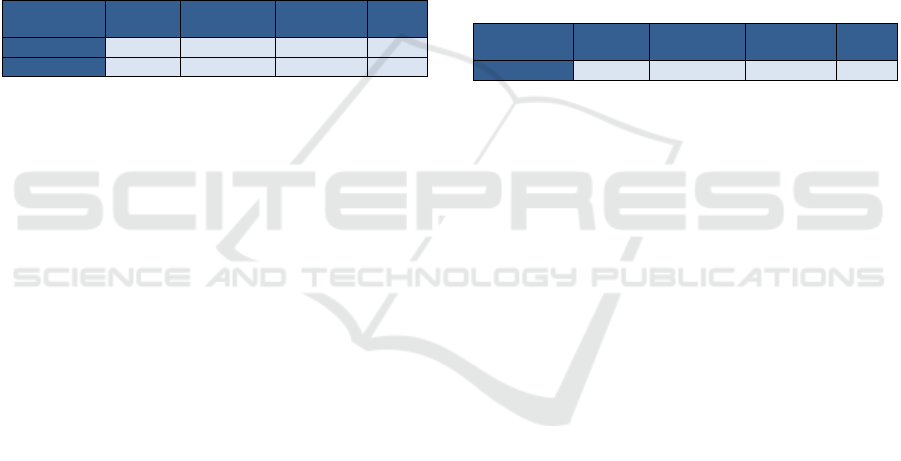

and 10 the knowledge. Table 1 reports the average

scores for each section of the assessment

questionnaire.

Table 1: Iteration 1 assessment scores.

Attitude

Attitude

Knowledge

Behavioral

Intent

Total

Assessment 1

4 6 6 53%

Assessment 2

5 9 7 70%

The employees’ knowledge increased by 30%

while their attitude and behavioral intentions

increased by 10% each. The overall impact of the

awareness campaign was 17%. It was rather

disturbing to observe that the employees’ attitude

towards information security remained very low

scoring – the least of the three. This study suggests

that this low attitude and intent change was due to the

campaign philosophies used. The African

information security awareness model was then

developed and validated in iteration 2.

Iteration 2

During this iteration, the way employees are

perceived was changed from viewing them as

individual entities to viewing them as members of a

group. We viewed employees as beings that are part

of a community that learn from one another and also

having the ability to teach others what they have

learnt in informal groups.

Unlike the previous iteration that had three

activities, this iteration only had two activities. The

first activity for this iteration was an information

security awareness campaign. This campaign took

advantage of the mob mentality of the employees.

The competitive advantages of Ubuntu discussed in

the prior sections were implemented. For instance, the

researchers and the organization’s management

agreed to train a person that seemed to be well

respectable in the Ubuntu hierarchy to lead the

organization’s awareness campaign discussions. This

seemed to have created interest amongst the peers.

The awareness campaign sessions in this iteration

were in the form of 3 lunch and learns.

The second and last of this activity of the second

iteration was then to assess to see if the model had

caused any positive change. The way this iteration

was conducted was identical to the two assessments

in the earlier iteration. The findings of this iteration

show a 30% change in attitude, 10% in behavioral

intent, no change in knowledge and 13% overall

change. We strongly believe that the change in

attitude and behavioral intent was due to the

employees realizing that they were in this together

and that that the insecurity of one employee will have

a negative effect on the whole team. In addition, the

group gathering made it feel more natural to them

because it is what they are used to in the Ubuntu

system.

Table 2: Iteration 2 assessment scores.

Attitude Knowledge

Behavioral

Intent

Total

Assessment 3

8 9 8 83%

7 LIMITATIONS AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

This study acknowledges naïve mistakes and

intentional security as two types of employee threats.

However, this study only addressed the threat from

naïve employees, although reviewed literature also

indicates that disgruntled employees or poor technical

infrastructure may also pose a serious security risk.

The researchers acknowledge an inadequacy of

human psychology critical review of literature

because the researchers have limited skills in social

science-based critical review; thus, the researcher

limited the literature review to the works of the most

influential theorists in the domain.

8 CONCLUSIONS

It is of great importance that information security

awareness should be highly regarded by all African

countries.

This study revealed that information security

awareness and training initiatives in Africa are not

taking advantage of Ubuntu in making their

campaigns more effective, rather they are mimicking

Western ideology based campaigns without taking

into account that the African society is different to

Western societies.

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

574

The primary contribution of this study was the

designing and validation of an African information

security awareness and compliance model.

Fundamentally, this model and its theoretical

foundations extended the body of existing knowledge

and also assisted in proving that indeed an African

philosophy based awareness campaign will produce

better results in Africa as compared to the Western

philosophy based.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank ABSA bank for a research grant

that made this research possible.

REFERENCES

Afro-centric Alliance, A. (2001). Indigenising organisational

change: Localisation in Tanzania and Malawi. Journal of

Managerial Psychology, 16(1), 59–78.

Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour:

Reactions and reflections. Taylor & Francis.

Allam, S., Flowerday, S. V., & Flowerday, E. (2014).

Smartphone information security awareness: A victim of

operational pressures. Computers & Security, 42, 56–65.

Alshboul, Y., & Streff, K. (2017). Beyond Cybersecurity

Awareness: Antecedents and Satisfaction. Proceedings

of the 2017 International Conference on Software and

E-Business, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1145/3178212.

3178218

Bauer, S., Bernroider, E. W. N., & Chudzikowski, K.

(2017). Prevention is better than cure! Designing

information security awareness programs to overcome

users’ non-compliance with information security

policies in banks. Computers & Security, 68, 145–159.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2017.04.009

Broodryk, J. (2005). Ubuntu management philosophy:

Exporting ancient African wisdom into the global

world. Knowres Publishing.

Chitumba, W. (2013). University education for personhood

through ubuntu philosophy. International Journal of

Asian Social Science, 3(5), 1268–1276.

Chua, H. N., Wong, S. F., Low, Y. C., & Chang, Y. (2018).

Impact of employees’ demographic characteristics on

the awareness and compliance of information security

policy in organizations. Telematics and Informatics,

35(6), 1770–1780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.

05.005

Davison, R., Martinsons, M. G., & Kock, N. (2004).

Principles of canonical action research. Information

Systems Journal, 14(1), 65–86.

Dearden, J., & Miller, A. (2006). Effective multi-agency

working: A grounded theory of ‘high profile’ casework

that resulted in a positive outcome for a young person

in public care. Educational and Child Psychology,

23(4), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajpem.v26i4.

31495

Fraser-Moleketi, G. (2009). Towards a common

understanding of corruption in Africa. Public Policy

and Administration, 24(3), 331–338.

Gianan, N. (2011). Delving into the ethical dimension of

Ubuntu philosophy. Cultura, 8(1), 63–82.

Gianan, N. A. (2010). Valuing the emergence of Ubuntu

philosophy. Cultura International Journal of

Philosophy of Culture and Axiology, 7(1), 86–96.

Gundu, T. (2019a). Acknowledging and Reducing the

Knowing and Doing gap in Employee Cybersecurity

Compliance—ProQuest. International Conference on

Cyber Warfare and Security

. Presented at the

International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security,

Stellenbosch. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.

com/openview/e99648655450412b824882dd31b16e8b/

1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=396500

Gundu, T. (2019b). Big Data, Big Security, and Privacy

Risks: Bridging Employee Knowledge and Actions

Gap | Journal of Information Warfare. Journal of

Information Warfare, 18(2), 15–30.

Gundu, T., Maronga, M., & Boucher, D. (2019). Industry

4.0 Businesses Environments: Fostering Cyber Security

Culture in a Culturally Diverse workplace. Kalpa

Publications in Computing, 12, 85–94.

https://doi.org/10.29007/r64x

Gundu, T., & Maronga, V. (2019). IoT Security and

Privacy: Turning on the Human Firewall in Smart

Farming. Kalpa Publications in Computing, 12, 95–

104. https://doi.org/10.29007/j2z7

Herath, T., & Rao, H. R. (2009). Encouraging information

security behaviors in organizations: Role of penalties,

pressures and perceived effectiveness. Decision

Support Systems, 47(2), 154–165.

Ifinedo, P. (2014). Information systems security policy

compliance: An empirical study of the effects of

socialisation, influence, and cognition. Information &

Management, 51(1), 69–79.

Khomba, J. K., & Kangaude-Ulaya, E. C. (2013).

Indigenisation of corporate strategies in Africa:

Lessons from the African ubuntu philosophy. China-

USA Business Review, 12(7).

Kruger, H. A., & Kearney, W. D. (2005). Measuring

information security awareness: A West Africa gold

mining environment case study.

Mangaliso, M. P., Mangaliso, Z., Knipes, B. J., Jean-Denis,

H., & Ndanga, L. (2018). Invoking Ubuntu Philosophy

as a Source of Harmonious Organizational

Management. Academy of Management Proceedings,

2018(1), 15007. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2018.

15007abstract

McCormac, A., Calic, D., Parsons, K., Butavicius, M.,

Pattinson, M., & Lillie, M. (2018). The effect of

resilience and job stress on information security

awareness. Information and Computer Security, 26(3),

277–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICS-03-2018-0032

Moorman, R. H., & Blakely, G. L. (1995). Individualism-

collectivism as an individual difference predictor of

organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of

Building Competitive Advantage from Ubuntu: An African Information Security Awareness Model

575

Organizational Behavior, 16(2), 127–142.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160204

Muwanga-Zake, J. W. (2009). Building bridges across

knowledge systems: Ubuntu and participative research

paradigms in Bantu communities. Discourse: Studies in

the Cultural Politics of Education, 30(4), 413–426.

Renaud, K., Flowerday, S., Othmane, L., & Volkamer, M.

(2015). “I Am Because We Are”: Developing and

Nurturing an African Digital Security Culture. African

Cyber Citizenship Conference 2015 (ACCC2015), 94.

Russell, C. (2002). Security Awareness—Implementing an

Effective Strategy. 16.

Rwelamila, P. D., Talukhaba, A. A., & Ngowi, A. B.

(1999). Tracing the African Project Failure Syndrome:

The significance of ‘ubuntu’. Engineering,

Construction and Architectural Management, 6(4),

335–346.

Safa, N. S., Sookhak, M., Von Solms, R., Furnell, S., Ghani,

N. A., & Herawan, T. (2015). Information security

conscious care behaviour formation in organizations.

Computers & Security, 53, 65–78.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2015.05.012

Shaw, R. S., Chen, C. C., Harris, A. L., & Huang, H.-J.

(2009). The impact of information richness on

information security awareness training effectiveness.

Computers & Education, 52(1), 92–100.

Sherif, E., Furnell, S., & Clarke, N. (2015). Awareness,

behaviour and culture: The ABC in cultivating security

compliance. Internet Technology and Secured

Transactions (ICITST), 2015 10th International

Conference For, 90–94. IEEE.

Shropshire, J., Warkentin, M., & Sharma, S. (2015).

Personality, attitudes, and intentions: Predicting initial

adoption of information security behavior. Computers

& Security, 49, 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

cose.2015.01.002

Siponen, M., Mahmood, M. A., & Pahnila, S. (2014).

Employees’ adherence to information security policies:

An exploratory field study. Information &

Management, 51(2), 217–224.

Steele, S., & Wargo, C. (2007). An introduction to insider

threat management. Information Systems Security,

16(1), 23–33.

Talaei-Khoei, A., Solvoll, T., Ray, P., & Parameshwaran,

N. (2012). Maintaining awareness using policies;

Enabling agents to identify relevance of information.

Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 78(1), 370–

391.

Tutu, D. (2004). Desmond Tutu: A biography. Greenwood

Publishing Group.

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2014).

Tackling the challenges of cyber security in Africa.

Policy Brief

, 01, 1–4.

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

576