External Contextual Factors in Information Security Behaviour

D. P. Snyman

a

and H. A. Kruger

b

School of Computer Science and Information Systems, North-West University, 11 Hoffman Street,

Potchefstroom, South Africa

Keywords: Information Security Behaviour, Contextual Factors, Human Factor in Information Security.

Abstract: Human behaviour is often considered to be irrational, difficult to understand, and challenging to manage. This

phenomenon has a direct impact on the way in which humans behave when confronted with information

security which, in turn, complicates how security is to be managed. This research attempts to investigate the

role that contextual factors play in how humans behave, specifically with regards to information security.

Contextual factors are identified that influence human behaviour in general. These factors are conceptualised

in relation to existing models of behaviour and subsequently mapped to information security behaviour. A

practical research exercise, relating to information security behaviour, is conducted with a university

residence as the contextual environment. The specific contextual factors, and how they relate to information

security, are discussed. Information security behavioural threshold analysis is employed to evaluate the impact

of the identified contextual factors on the residence’s security behaviour. The results are reflected upon, based

on the results from the threshold analysis. The paper concludes by highlighting the contributions that were

made towards understanding contextual factors in information security.

1 INTRODUCTION

The digitalisation of everyday activities is rapidly

expanding to include even the most basic day-to-day

interactions with people and (previously undigitized)

systems (Scholl, 2018). This has given rise to an

enhanced awareness and responsibility that regulators

and governments have in providing frameworks that

facilitate and prescribe the protection of the

information and privacy of individuals, for instance,

the General Data Protection Regulation in Europe.

Similarly, organisations have a heightened

responsibility and, given the regulatory frameworks,

a level of accountability in safeguarding the

information of customers and employees alike.

While these developments in information security

enhancement are noble in concept, the actualisation

thereof remains complicated. Even within the strict

demands on organisations and their adherence

thereto, one of the prevailing threats to the

information security of the end-users remains the

users themselves. One would argue that when

individuals are given the opportunity to protect their

privacy and information security interests they would

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7360-3214

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8514-4422

do so with due consideration. However, this is rather

the exception than the rule given the occurrence of

phenomena like the privacy paradox, i.e. the wilful

disclosure of one’s private information, even when

such disclosure is known to be ill-advised (Barth et

al., 2019). This unpredictability of the human factor

in information security remains difficult to

understand and therefore difficult to manage. In an

attempt to gain better insight into the reasons for

inconsistent and often contradictory behaviour,

information security and privacy research is often

concerned with the underlying factors that drive

behaviour when people are presented with the

abovementioned digitised interactions (Scholl, 2018).

Among the different approaches to analyse

information security behaviour, psychological

models are often employed to explain the way in

which the thought processes work that eventually lead

to a specific behaviour or course of action. Most

studies on human behaviour focus on the internal

thought processes and motivations that inform

intention and, eventually, the behaviour of a person.

Some or other psychological theory or model of

behaviour is usually employed as a guiding

Snyman, D. and Kruger, H.

External Contextual Factors in Information Security Behaviour.

DOI: 10.5220/0009142201850194

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2020), pages 185-194

ISBN: 978-989-758-399-5; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

185

framework for research in this field. A few of the

more commonly used theories include knowledge,

attitude, behaviour (KAB), the theory of reasoned

action (TRA) (Shropshire et al., 2015), protection

motivation theory (PMT) (Parsons et al., 2017), and

the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Parsons et al.,

2017). Such models are usually focussed on the

intrinsic processes of an individual’s cognition and

rarely (if ever) consider the setting that an individual

finds themselves in.

In contrast thereto, earlier work by Willison and

Warkentin (Willison and Warkentin, 2013) postulates

that understanding the mutual interaction of thought

processes and organisational context is important to

effectively employ information security controls in an

organisation. This is confirmed by more recent

literature (Kroenung and Eckhardt, 2015; Johnston et

al., 2019; Wu et al., 2019) which has further identified

that there is an ongoing need for approaches and

methods that bridge the gap in information security

research by both understanding the context of an

individual and, where applicable, factoring

contextual factors into any analysis that attempts to

quantify information security behaviour.

In an attempt to contribute to filling the

abovementioned gap, the aim of this research is

therefore to 1) theorise on the external factors (i.e.

external to an individual) that influence information

security behaviour, and 2) to present the application

of a model that takes context into account and predicts

information security behaviour of a group.

The remainder of the paper is structured as

follows: Section II describes factors that typically

influence human behaviour, and thereafter Section III

shows how these factors relate to information security

behaviour. In Section IV, a cursory introduction into

a model that considers contextual factors in

information security behaviour is presented along

with the findings of a real-world application thereof.

The study concludes in Section V with a reflection on

the study and a look ahead to possible future work.

2 CONTEXTUAL FACTORS IN

HUMAN BEHAVIOUR

In the preceding Introduction, the need to

conceptualize and understand the contextual factors

that influence information security behaviour was

highlighted. In order to eventually bring about a

discussion of these factors in terms of information

security, a discussion of contextual factors is first

presented here in general terms, i.e. factors that

influence everyday behaviour.

In a recent study, Kirova and Thanh (2019), based

on the influential earlier work of Belk (1975),

investigate the contextual factors that influence

smartphone use. They identify five common aspects

of all circumstances that can be used to identify the

influences that are exerted upon an individual. These

aspects are listed below:

Physical milieu;

Social milieu;

Perspective of elapsed (or remaining) time;

Individual predisposition; and

Individual intention.

Even though these factors are all conceptualised

as being contextual in nature and they all contribute

to the experience and environment in which

behaviour is to be actualised, for the purposes of this

paper they may be classified as being either an

intrinsic or an extrinsic factor, i.e. intrinsic or

extrinsic to an individual. The contextual factors may

be grouped as follows in Table 1.

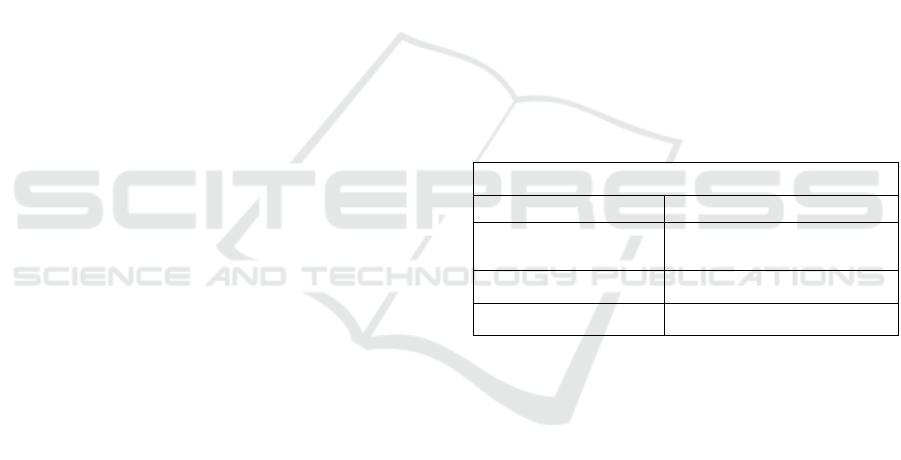

Table 1: Categorisation of contextual factors in behaviour.

Contextual factors in behaviour

Extrinsic factors Intrinsic factors

Physical milieu

Perspective of elapsed (or

remaining) time

Social milieu Individual predisposition

Individual intention

As mentioned before, when psychological

theories and models are compared to the classification

of the contextual factors in Table 1, one commonality

may be identified. Many of these theories are centred

around the intrinsic factors, e.g. individual

predisposition (which relates to intention). Intention

is one of the core indicators which guides behaviour

in the TPB. The extrinsic factors are not explicitly

provided for in these frameworks.

Given that intrinsic factors are already considered

in these theories, this research focusses on the

extrinsic factors and how they influence one’s

behaviour. A short description is provided below for

each of the extrinsic factors from Table 1:

The physical milieu is an aspect that is derived

from the tangible environment in which an individual

finds themselves. This aspect considers the

characteristics that define the physical experience that

relate to what someone sees, feels (touch), hears,

tastes, and smells.

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

186

Social milieu refers to the influence that other

people have on an individual. They may be present in

the environment (direct influence by example) or

influence an individual through some other means

like through digital interactions. An individual may

either be formally acquainted with these influencers

(e.g. friends, co-workers, or family) or be wholly

unfamiliar (e.g. shop attendants or internet

personalities).

Recall that the first aim of this paper is to theorise

on external factors in information security behaviour.

To satisfy this aim the aforementioned extrinsic

contextual factors will be contextualised in terms of

information security in the following section.

3 EXTERNAL CONTEXTUAL

FACTORS IN INFORMATION

SECURITY BEHAVIOUR

Two extrinsic contextual factors in behaviour have

been identified in the previous section namely,

physical milieu, and social milieu. In terms of

information security behaviour, it is imperative to

understand how these external factors manifest in the

environments where security behaviour is performed.

For instance, the physical milieu does not only relate

to aspects that may be observed through one’s senses,

but also relates to aspects such as access to

information, and convenience. Social milieu may also

relate to aspects of interactions with others that are

more intangible, e.g. body language, and peer

pressure. Table 2 shows some typical material

examples of the forms which these factors may adopt

in relation to information security behaviour. These

examples are presented here (and later in Table 3) as

conceptualised by the authors based on characteristic

information security behaviours and university

residence environments, and how they might relate to

the extrinsic factors as identified from the work of

Kirova and Thanh (2019). The examples listed in this

paper are by no means exhaustive and many more

may exist.

In a related study, Snyman and Kruger (2017)

investigate information security behaviour in terms of

the TPB model. What differentiates their study from

other studies that are based on the same model, is that

the study speculates on the applicability of contextual

influences on behaviour alongside the existing

intrinsic factors that the model is based on. Such

contextual influences are only described in theoretical

terms and further investigation was left for future

work. In an attempt to build on this initial

groundwork, their approach, together with the two

external contextual factors identified above, will be

used to guide the practical part of this research.

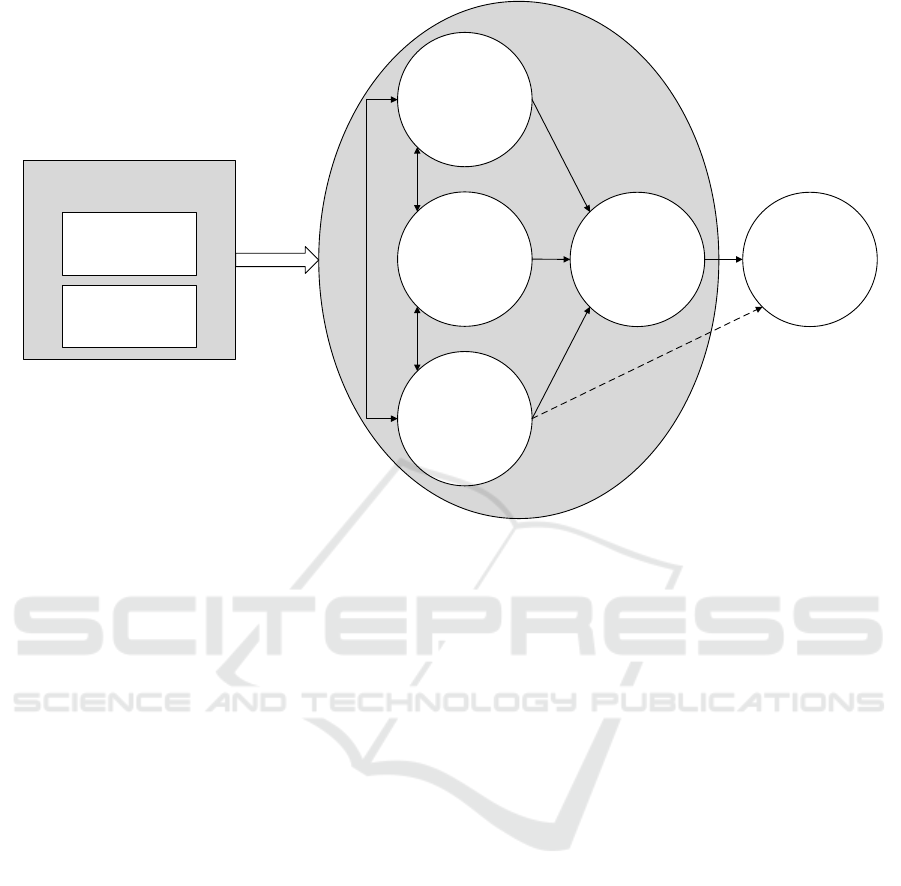

To contextualise the TPB (as applied in (Snyman

and Kruger, 2017)) with the current research

presented in this paper, a graphical depiction is

provided in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows a conceptual

diagram of the interaction between the TPB and the

external contextual factors. From the figure, it can be

seen that the external (extrinsic) factors have an

influence on the intrinsic factors. It is in the context

of the intrinsic factors that the TPB then describes

how attitude, norms and behavioural control guide the

eventual behaviour of a person. Snyman and Kruger

(2017) further argue that an approach that is able to

implicitly capture information about external factors,

and use this information in predicting eventual

behaviour, are the so-called Threshold models of

collective behaviour as envisioned by Granovetter

(1978).

Table 2: General external factors that influence information security behaviour.

External factors in information security behaviour

General extrinsic factor Example of extrinsic factor that influences security behaviour

Physical milieu

Ease of access to systems, processes and people.

Level of convenience associated with certain tasks.

Availability of technical expertise.

Presence of security controls.

Social milieu

Peer pressure

Presence of co-workers/family/friends.

Organisational structure.

Required to work together with others.

Collective purpose.

Exposed to the actions/behaviours of others.

External Contextual Factors in Information Security Behaviour

187

External (extrinsic) factors that

influence behaviour

Subjective norm

Perceived behavioural

control

Attitude towards

behaviour

Intention Behaviour

Physical milieu

Social milieu

Intrinsic factors

Figure 1: Conceptual model of the influence of contextual factors in relation to the TPB.

He argues, and mathematically motivates, that

human behaviour is guided by the example that is set

by others, i.e. an extrinsic factor. A person is

presumed to always try and increase their utility

within a given situation, guided by a perceived

cost/benefit trade-off of participating in a certain

behaviour, juxtaposed by choosing not to participate.

The assumption is made that there are only two

opposing options for the behaviour, i.e. no third (or

additional) option(s) exists, and one must choose

either of the outcomes that participation or abstinence

convey.

People are assumed to be rational in their

decision-making, always favouring benefit over cost.

However, as the number of other people that perform

a specific behaviour increases, a mental shift occurs

that causes the perceived benefit to rise to a level that

exceeds the perceived cost that is associated with the

behaviour, even if the contrary was initially true. This

pivotal point in the decision-making process may be

described by an examination of the concept of

behavioural thresholds.

Granovetter (1978) hypothesises that each

individual has an intrinsic threshold for participation

in behaviour. This threshold may be expressed as the

number of other people that should first be engaging

in a behaviour before the associated benefit will

outweigh the cost in the individual’s mind. At this

point, it should be noted that when a person perceives

the benefit to outweigh the cost from their

perspective, without needing any external influence,

that they will perform a behaviour of their own

accord. Such individuals may be referred to as

instigators. They are required, especially in a high-

cost situation, to be the catalyst that influences others

to follow their example.

In order to apply this theoretical model in a real-

world situation, behavioural threshold analysis is

employed. This analysis entails that the threshold

values for participation in a behaviour is known for

each of the group members and is dependent on, and

specific to, the composition of individuals that

constitute the group. The process by which these

individual thresholds may be elicited from the group

members by means of self-reporting questionnaires is

presented in (Snyman and Kruger, 2019). Given the

individual thresholds, mathematical aggregation is

used to provide an outlook for the eventual group

behaviour.

To relate the threshold model and analysis of

Granovetter (1978) back to information security, a

practical exercise was conducted which is described

in the following section.

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

188

4 EXPERIMENTAL

BACKGROUND

Taking inspiration from a similar exercise which was

conducted in an industry setting (Snyman et al.,

2018), a behavioural threshold analysis experiment

was conducted to examine the information security

behaviour of students at a predominantly residential

South African university. The experiment was

specifically designed with a new set of contextual

factors in mind when compared to that of (Snyman et

al., 2018). In contrast to the industry setting in

(Snyman et al., 2018), the context of the university

students is one of living together in a university

residence. A description of these specific contextual

factors, in reference to the general factors in Table 2,

is given below in terms of the physical milieu and the

social milieu.

Physical Milieu – A university residence, as

mentioned above, physically consists of common

areas (lounges, television rooms, kitchens, laundry

rooms, public computer rooms, reception), as well as

private sleeping quarters which houses one or two

students per room. The close proximity of this kind of

living arrangement provides the members of the

residence with unprecedented access to the behaviour

of others. Both in practical terms that allow the

observation of the behaviour of others, and physical

terms in which access is afforded to personal and

university computers and networks.

A certain level of convenience is conveyed by

living in close quarters. For instance, if network

access is required after business hours and a person’s

credentials have expired, it is easy to simply ask any

other inhabitant of the residence to supply their

details. It is convenient for the borrower as their

ability to access the network is instantly restored

without the need to contact the help-desk which will

not respond in real-time.

Given the combination of different academic

levels and technical proficiencies that cohabit, it is

probable that someone with a high level of know-how

or expertise can readily be found to help circumvent

security controls that stand in the way of quickly or

conveniently completing a task.

An example of such a circumvention is accessing

dubious websites that are restricted on the university

network by means of masking their network traffic by

employing virtual private networks to third party

providers. In these cursory examples, one sees that

the physical milieu provides means and opportunity

to engage in risky information security behaviour.

The social milieu, described below, may help provide

the motive.

Social Milieu – University residences are a

socially rich environment with a unique culture. This

gives rise to many interactions between people that

may influence how they behave. In information

security terms, this influence may contribute to bad

security behaviour in the following ways:

In a residence, there is a constant presence of other

people. Even in a private space like sleeping quarters,

there might be another resident present. This implies

that some actions of an individual, that would

normally go unnoticed, are being observed. If they

visit a dubious website, someone may be there to

observe it. When password sharing occurs between

two parties it may be witnessed by any or all of the

others present. Therefore, this constant presence may

convey an unprecedented sense of awareness of the

information security habits of the resident corps. The

awareness may set the precedent for future behaviour.

Peer pressure is ever-present in university

residences (Johnson et al., 2005; Young and de Klerk,

2008; de Klerk, 2013). A strict hierarchy prevails

where a pecking order distinction is made based on

the number of years someone has been residing in the

specific residence. There is also a specific distinction

between junior (usually first-year students or first-

time entrants) and senior students. In this hierarchy,

juniors have very little autonomy and, especially

during an initial orientation, are forced to obey senior

residents (de Klerk, 2013). The peer pressure and

hierarchy that is present in residences are usually seen

as factors in hazing (de Klerk, 2013) and alcohol

consumption in literature (Johnson et al., 2005;

Young and de Klerk, 2008) but is also applicable to

security behaviour. A resident may easily be coerced,

through this hierarchical structure and peer pressure,

into divulging credentials, not reporting security

circumventions, downloading illicit content, etc.

Even though the hierarchy may be seen in a

negative light as illustrated above, it may also

contribute to a sense of belonging and camaraderie

(de Klerk, 2013). There is an implied level of trust

associated with shared experiences. This is

compounded by the compulsory attendance of events

(Johnson et al., 2005; de Klerk, 2013) that are meant

to reaffirm the bond between the residents. This trust

allows for a false sense of safety where security is

concerned. For instance, one might not appropriately

scrutinise an email that was (presumably) sent by a

confidant and assume it to be safe. The assumption

will leave one open to malware and phishing attacks.

Extending Table 2, Table 3 summarises the extrinsic

factors (as described in Section II) that relate to the

context of students living together in a residence.

External Contextual Factors in Information Security Behaviour

189

Table 3: External factors in student residence living that influence information security behaviour.

External factors in information security behaviour

Extrinsic factor Factors in general security behaviour Factors in student security behaviour

Physical milieu

Ease of access to systems, processes and

people.

Level of convenience associated with certain

tasks.

Availability of, and access to expertise.

Presence of security controls.

Close quarters living provides access and

convenience.

Dissemination of security control workarounds

from observation and readily available expertise.

Social milieu

Peer pressure from others.

Constant presence of co-

workers/family/friends.

Hierarchy of persons in an organisation.

Required to work together with others.

Sense of collective purpose.

Exposed to the actions/behaviours of others.

Peer pressure, often hierarchy based, from more

senior and other residents to disclose private

information, e.g. network credentials.

Constant presence of other residents, even in

private quarters. Security behaviours may be easily

observed.

Implied trust due to camaraderie and shared

experiences (based on compulsory attendance of

events) leads to false sense of safety and security.

Information security behavioural threshold

analysis from (Snyman and Kruger, 2019) was

subsequently implemented in the specific context as

described above. For a detail description on

behavioural threshold analysis in general terms, the

reader is referred to (Granovetter, 1978) as only a

brief overview is presented here due to page

restriction considerations.

The threshold questionnaires were digitally

distributed to 186 residents at a single-sex (male)

university residence. Participation was voluntary and

all responses were anonymous. Due to the relatively

sensitive nature of questions that relate to personal

information security behaviour, along with

participation not being compulsory, suitable

responses were obtained from 52 respondents

resulting in a 28% response rate.

The questionnaire consisted of five questions

relating to information security behaviours. To cover

a range of common information security themes,

selected focus areas of the Human Aspects of

Information Security Questionnaire (HAISQ) were

employed as the topics for the questions (Parsons et

al., 2017). The five questions related to

password management, incident reporting, social

media use, internet use, and email use.

A four-point Likert scale was used for the

question responses. The respondents rate their

predisposition for participating in the security

behaviour, relative to the percentage of other group

members that perform the behaviour (Snyman and

Kruger, 2019). This predisposition for participation is

used as the behavioural threshold for the respondent.

Responses from all the respondents were

mathematically aggregated and analysed.

In addition to the questions above that relate to

information security, the questionnaire was

supplemented with questions relating to biographic

information as summarised above. Moreover, the

respondents were asked to rank their own confidence

(five-point Likert scale) in the use of technology (in

broad terms), and more specifically, their confidence

in respect to information security.

Of these 52 respondents, 17 were self-identified

as first-years (typically 19 years old), 15 as second

years (20 years old), 13 as third years (21 years old),

and 7 as being fourth-year and above (22 years old

and over). Additionally, 7 academic faculties were

represented in the responses namely, Faculties of

Education, Engineering, Natural sciences,

Economics, Health sciences, Humanities, and Law.

The distribution of responses per faculty is presented

in Figure 2 below.

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

190

Figure 2: Distribution of responses per faculty.

The relatively low response rate and the possible

influence of phenomena such as selection bias

notwithstanding, the distribution between four year-

groups and seven faculties were considered to be

representative enough to allow for the useful

application of information security behavioural

threshold analysis (Snyman and Kruger, 2019). Thus,

no attempt was made to address the possible selection

bias in this specific context but may be investigated

as a possible extension of this study in future work.

In the following section, a reflection is provided

on the aforementioned contextual factors and how

they are echoed in the behavioural threshold analysis

results.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

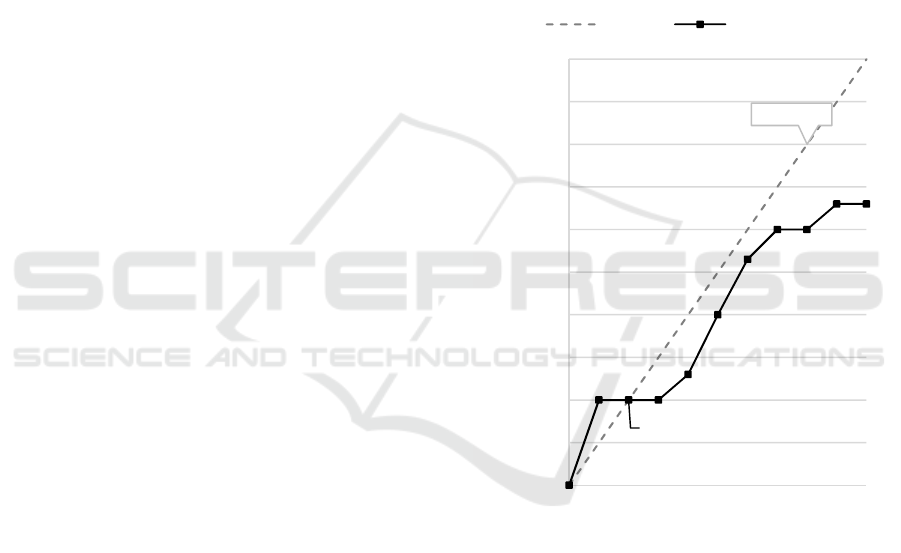

To interpret the behavioural thresholds that were

reported by the respondents, the thresholds are

aggregated by calculating the cumulative frequencies

for each threshold interval. In order to simplify the

analysis, behavioural thresholds are grouped into

intervals of 10%. These frequencies are then graphed

as a line of participation level versus cumulative

behavioural thresholds . Furthermore,

Granovetter (1978) stipulates that the cumulative

frequencies of the respondents’ behavioural

thresholds should be graphed in relation to a uniform

distribution of thresholds. This uniform distribution is

referred to as the equilibrium line and is represented

by the line. The intersection (if present) of the

two lines may indicate that the group behaviour has

reached an equilibrium point, i.e. the number of

participants in the behaviour has stabilised.

Behaviour that has reached equilibrium will not gain

any new participants but neither will any participants

desist from their current behaviour.

Once again, due to the page limit, only one of the

abovementioned security topics (i.e. internet use) can

be shown here. Figure 3 shows the behavioural

threshold analysis graph for internet use for all the

respondents that live in the residence.

Given an initial stimulus like an instigator that

sparks the initial participation in a behaviour, the

number of people that exhibit the behaviour will most

likely grow.

Figure 3: Behavioural threshold analysis graph – Internet

use (All respondents).

From Figure 3, participation in inadvisable

behaviour, relating to internet use, is predicted to

increase to a level where 69% of the inhabitants of the

residence will be performing the unwanted behaviour

if 70% of the group are already performing (or

thought to be performing) the behaviour. It should be

noted that the 70% do not actually have to exhibit the

behaviour. The mere perception that a number of

others are performing the behaviour is enough to

exceed the individual thresholds.

The number of residents that partake in the

behaviour stabilises at this point. This can be deduced

from the intersection of the cumulative threshold line

with the equilibrium line at the point 70, 69.

Granovetter (1978) states that the requirement for

equilibrium is that the two line segments to the left

and right of the intersection have gradients

∆ ∆

⁄

of less than one.

Economics

17%

Education

15%

Engineerin

g

21%

Health

Sciences…

Humanities

4%

Law

6%

Natural

Sciences

31%

Equilibrium

70, 69

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 102030405060708090100

Percentage of respondents who access

dubious websites (Internet use - All respondents)

Behavioural thresholds

Equilibrium

Cumulative thresholds

External Contextual Factors in Information Security Behaviour

191

This implies that an equilibrium state requires the

threshold line to intersect the equilibrium line from

above. An intersection from below does not constitute

an equilibrium state, i.e. the gradient is greater than

one. When 1 to the left of the intersection, the

number of participants will not decrease in and of

itself. An external influence or stimulus (e.g.

information security training or awareness

campaigns) is required to reduce the participation

rate. In the same manner, to the right of the

intersection, the number of participants will not

increase.

When relating the participation in internet use to

the two external contextual factors that were

mentioned earlier, i.e. physical and social factors, the

influence thereof becomes apparent. The

participation rate of 69% indicates that the

respondents, who all live in the residence, are quite

willing to follow the example of their fellow

residents. Their behavioural thresholds are low, i.e. it

takes little motivation or the perception that only a

few others already perform the behaviour, for them to

also perform the behaviour.

On the physical level, this may be attributed to the

access that the respondents have to technologically

knowledgeable peers. An example scenario can

include that institutions often employ firewalls and

other network tools to prohibit access to websites and

other network protocols they deem to be dubious in

terms of security or questionable in terms of the

content they provide (Miller and Stuart Wells, 2007).

Examples of these types of websites include, among

others, so-called torrent sites which provide unpaid

access to copyrighted materials via peer-to-peer

networks. Illegally downloading these materials are a

frequent occurrence in tertiary institutions (Gan and

Koh, 2006; Lee et al., 2019). Residences provide the

ideal environment where these restrictions may be

circumvented by a knowledgeable person and the

method of access disseminated to others.

The social factor then determines how

dissemination might take place: The required

awareness that such circumventions are possible is

created through constant presence and observation.

The person that originally exploited the

circumvention is then either coerced to help others

bypass the existing security (through peer pressure or

levels of hierarchy) or might provide others with the

solution willingly because of a sense of solidarity and

collective purpose. These factors are therefore

reflected in the willingness of 69% of the respondents

for accessing dubious websites, given that a critical

number of others in the residence already do it.

As mentioned before, the graph in Figure 3 is

representative of the predicted behaviour for the

entire surveyed group. A question that asks

respondents to identify the number of years that they

have been living in the residence was added to the

questionnaire beforehand which allows one to drill

down and identify behaviour for sub-groupings

within the greater group. A finer-grained approach

allows for a more comprehensive analysis. This

allows for pinpointing where different groupings are

persuaded to follow security behaviour differently.

To illustrate this difference, the same internet use

example which was presented for all the respondents

in Figure 3, is now presented for a smaller grouping

in Figure 4, i.e. first-year residents.

Figure 4: Behavioural threshold analysis graph – Internet

use (First-years).

Following the same analysis as described above,

it is interesting to see that the predicted participation

rate for adopting unwanted internet use behaviour for

first-years (20%) is considerably lower than that of

the greater group at 69%.

This implies that the first-years’ thresholds for

participation is higher in comparison with the greater

group. They are therefore less likely to be influenced

in participating in the undesirable security behaviour.

In this research, the self-assigned grouping

classification of first-year is taken to indicate that the

respondent has entered the residence for the first time

Equilibrium

20, 20

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 102030405060708090100

Percentage of respondents who access

dubious websites (Internet use - First-years)

Behavioural thresholds

Equilibrium Cumulative thresholds

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

192

at the start of the current academic year. This means

that, by the time of distributing the questionnaires to

the residents, first-years would only have been

staying in the residence between one to two months.

It stands to reason that the limited time that they were

functioning in this environment would mean that the

physical and social factors would not have been

experienced as strongly as the other groupings who

have typically been living in the residence for at least

more than a year.

The concept of access to expertise, as a physical

factor, only works if there is a certain rapport that

exists between the parties. A first-year might not (yet)

have the required level of acquaintance or

hierarchical standing (social factor) that affords this

access. Furthermore, first-years do not necessarily

have a sense of camaraderie with the senior students

in the residence. There have not been enough shared

experiences in their frames of reference, but this

shared reference does exist between first-years as

they have undergone the same orientation period

when first joining the residence.

In the final section, the study is summarised. The

aims of the study are revisited, and a reflection is

provided on the contributions and limitations of this

research. A look ahead to possible future work

concludes the article.

6 CONCLUSION

In this paper, an investigation was conducted into

contextual factors that might influence information

security behaviour. Section II described contextual

factors that might influence human behaviour.

Section III related these contextual factors to

information security behaviour. Behavioural

threshold analysis, which might consider contextual

factors in information security behaviour, was

presented in Section IV and selected findings of an

application thereof were highlighted.

In Section 1 the original aims of this research were

presented and are therefore reflected upon here.

These aims are reiterated here and are subsequently

discussed. This study aimed to 1) theorise on the

external factors (i.e. external to an individual) that

influence information security behaviour, and 2) to

present the application of a model (behavioural

threshold analysis) that takes context into account and

predicts information security behaviour of a group.

These two aims were addressed as follows:

External contextual factors in information

security behaviour - Five contextual factors in human

behaviour were identified from literature. The

contribution of this research lies therein that these

contextual factors were grouped into two categories,

i.e. intrinsic factors and extrinsic factors. These

categories were then incorporated into a conceptual

framework relating to the Theory of Planned

Behaviour. Guided by this framework, the external

factors were linked with information security

behaviour in general. It was then motivated that the

Threshold Models of Collective Behaviour and

Behavioural Threshold Analysis could be applied to

measure security behaviour, given the influences of

the external contextual factors.

Information security behavioural threshold

analysis – In order to apply the aforementioned

behavioural threshold analysis, a research exercise

was conducted by distributing questionnaires on

group security behaviour at a university residence.

This research contributes by using this specific

contextual environment to explain what form the two

external factors that influence behaviour might take

on in terms of security behaviour within a university

residence. The results of the behavioural threshold

analysis were used to illustrate how the group (and a

sub-group) might eventually follow unwanted

security behaviour. Lastly, the two external

contextual factors were once again discussed with

reference to the outcomes of the exercise and how

these factors might differ between the main group and

the sub-group.

The aims, as reflected upon above, were met

amidst certain limitations which should be noted and

considered when the findings are interpreted: The

study was conducted at one single-sex residence. This

means that there is no corroborating evidence, of the

influence that these specific external factors have on

information security behaviour, from other

residences. Furthermore, only the two external

contextual factors, i.e. physical and social, were

incorporated in the analysis.

These limitations notwithstanding, this research

demonstrates that contextual factors (with specific

reference to extrinsic factors) play an important role

in information security behaviour. These factors may

be analysed by employing models such as

behavioural threshold analysis. Such an analysis may

provide a useful understanding of the human aspect

of information security, and related behaviours, in an

organisation. Better insight into these factors can

contribute to more effective management of the

human factor by guiding information security training

programs to address specific, rather than generic,

security behaviours.

Finally, future studies may consider studying how

the intrinsic factors (even though they are

External Contextual Factors in Information Security Behaviour

193

conceptually part of the TPB) are reflected in the

behavioural threshold analysis model.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr Johan Allers for

his assistance in distributing the questionnaire.

REFERENCES

Barth, S., De Jong, M. D., Junger, M., Hartel, P. H. &

Roppelt, J. C. 2019. Putting the privacy paradox to the

test: Online privacy and security behaviors among users

with technical knowledge, privacy awareness, and

financial resources. Telematics and Informatics, 41, 55-

69.

Belk, R. W. 1975. Situational variables and consumer

behavior. Journal of Consumer research, 2, 157-164.

de Klerk, V. 2013. Initiation, hazing or orientation? A case

study at a South African university. International

Research in Education, 1, 86-100.

Gan, L. L. & Koh, H. C. 2006. An empirical study of

software piracy among tertiary institutions in

Singapore. Information & Management, 43, 640-649.

Granovetter, M. 1978. Threshold models of collective

behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 83, 1420-

1443.

Johnson, A. M., Rodger, S. C., Harris, J. A., Edmunds, L.

A. & Wakabayashi, P. 2005. Predictors of alcohol

consumption in university residences. Journal of

Alcohol and Drug Education, 49, 9.

Johnston, A. C., Di Gangi, P. M., Howard, J. & Worrell, J.

2019. It Takes a Village: Understanding the Collective

Security Efficacy of Employee Groups. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 20, 186-212.

Kirova, V. & Thanh, T. V. 2019. Smartphone use during

the leisure theme park visit experience: The role of

contextual factors. Information & Management, 56,

742-753.

Kroenung, J. & Eckhardt, A. 2015. The attitude cube—A

three-dimensional model of situational factors in IS

adoption and their impact on the attitude–behavior

relationship. Information & Management, 52, 611-627.

Lee, B., Fenoff, R. & Paek, S. Y. 2019. Correlates of

participation in e-book piracy on campus. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 45, 299-304.

Miller, C. & Stuart Wells, F. 2007. Balancing security and

privacy in the digital workplace. Journal of Change

Management, 7, 315-328.

Parsons, K., Calic, D., Pattinson, M., Butavicius, M.,

McCormac, A. & Zwaans, T. 2017. The human aspects

of information security questionnaire (HAIS-Q): two

further validation studies. Computers & Security, 66,

40-51.

Scholl, M. 2018. Awareness in Information Security.

Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, 16, 80-89.

Shropshire, J., Warkentin, M. & Sharma, S. 2015.

Personality, attitudes, and intentions: Predicting initial

adoption of information security behavior. Computers

& Security, 49, 177-191.

Snyman, D. P. & Kruger, H. A. 2017. The application of

behavioural thresholds to analyse collective behaviour

in information security. Information & Computer

Security, 25, 152-164.

Snyman, D. P. & Kruger, H. A. 2019. Behavioural

threshold analysis: Methodological and practical

considerations for applications in information security.

Behaviour & Information Technology, 38, 1-19.

Snyman, D. P., Kruger, H. A. & Kearney, W. D. 2018. I

shall, we shall, and all others will: Paradoxical

Information Security Behaviour. Information &

Computer Security, 26, 290-305.

Willison, R. & Warkentin, M. 2013. Beyond deterrence: An

expanded view of employee computer abuse. MIS

quarterly, 37, 1-20.

Wu, P. F., Vitak, J. & Zimmer, M. T. 2019. A contextual

approach to information privacy research. Journal of

the Association for Information Science and

Technology, 1-6.

Young, C. & de Klerk, V. 2008. Patterns of alcohol use on

a South African university campus: The findings of two

annual drinking surveys. African Journal of Drug and

Alcohol Studies, 7, 101-112.

ICISSP 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

194