Perceiving the Focal Point of a Painting with AI: Case Studies on Works

of Luc Tuymans

Luc Steels

a

and Bj

¨

orn Wahle

Institut de Biologia Evolutiva, Universitat Pompeu Fabra and CSIC, Barcelona, Spain

Keywords:

Digital Humanities, Contemporary Painting, AI, Computer Vision, Iconography.

Abstract:

We report the first steps in investigating how we can use AI to study contemporary painting practices and

viewer experiences, focusing in particular on the work of Luc Tuymans. We review first various possible

aspects of painting that could be studied and point to some relevant AI techniques to do so. Then we zoom in

on one specific topic: How is a viewer guided to the focal point of the painting. This is not purely a matter

of visual perception but also of interpretation and meaning making. Painters deliberately create focal points

based on sophisticated knowledge of human perception and interpretation. Inspired by their insights and

practices we can use AI research to unpack the process and thus provide a more insightful characterization of

how paintings are perceived and made, compared to statistically derived embeddings. We argue that profound

challenges must still be overcome before AI systems handle the identification of focal points, let alone arrive

at the rich interpretations human viewers construct of paintings or other types of art works.

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of AI in digital humanities is increasing

steadily with important and successful applications

for managing and searching in existing collections or

performing historical art research. This work rests on

various AI techniques from pattern recognition, com-

puter vision, and information retrieval, augmented

with semantic web technologies ((Strezoski and Wor-

ring, 2017), (de Boer et al., 2013)) Other interac-

tions between AI and art have focused on capturing

the characteristics of artistic style in order to generate

new art works in the same style (Semmo et al., 2017).

Here we report on a rather different line of work

that is exploring how AI can model the process of per-

ceiving and interpreting the meaning of art works, in-

dividually or in context, i.e. the semantic understand-

ing of art (Garcia and Vogiatzis, 2018) We want to un-

pack the perceptual and interpretive processes that a

viewer goes through, using AI models as a vehicle for

examining these processes and studying their effect.

This has educational applications to help viewers have

richer experiences but also it is of interest to painters

because they can explore the effect of their work in a

novel way and possibly open innovative paths in the

creation of new art works. The AI systems and exper-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9134-3663

imental outcomes of our approach are a valuable addi-

tion to the traditional data gathered about art and can

be a complementary instrument for heritage preserva-

tion.

The present research is being conducted in inter-

action with the contemporary Flemish painter Luc

Tuymans. The role of a professional artist is cru-

cial for our project. We view him as a highly com-

petent expert in human perception and interpretation.

He uses these insights to create works that maximize

the artistic experience and achieve rich meaning con-

struction for his viewers. There are considerable ad-

vantages in working with a living artist because we

can get much more accurate data about the work, the

context of creation, the source materials of each work,

the texts written by curators or the artist himself, the

exhibition design process, and the intended meanings

(from the viewpoint of the artist - which may differ

from those of viewers). We can also get direct feed-

back about the results of running various AI experi-

ments and learn what the painter finds important and

relevant for the study of artistic practices.

The main source of data for the present research is

the complete collection of paintings of Tuymans (564

works), together with extensive meta-data methodi-

cally archived digitally and compiled in a ‘Catalogue

Raisonn

´

e’ (Meyer-Hermann, 2019), from which we

have extracted high quality digital images for each

Steels, L. and Wahle, B.

Perceiving the Focal Point of a Painting with AI: Case Studies on Works of Luc Tuymans.

DOI: 10.5220/0009163108950901

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2020) - Volume 2, pages 895-901

ISBN: 978-989-758-395-7; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

895

painting. From the digital archive maintained at Stu-

dio Luc Tuymans we have extracted other information

such as in which exhibitions paintings were shown, so

that we could explore the curatorial practices of Tuy-

mans through network analysis. This research is how-

ever not discussed in the present paper.

Our choice to work with Luc Tuymans has already

turned out to be very productive. The mastery and

artistic importance of Tuymans is not in dispute. He

has exhibited in Tate Modern London, Centre for Fine

Arts (BOZAR) Brussels, MOMA New York, Palazzo

Grassi Venice, and many other prestigious venues.

His work has a strong recognition in the art market

through the influential galeries of David Zwirner in

New York and Frank De Maegd (Zeno X) in Antwerp.

It is also very helpful that Tuymans is very articulate

in describing his artistic practice and there is an abun-

dant literature about his art, including interviews, cat-

alogs, art criticisms, and personal writings (Tuymans,

2018).

Even more importantly, the work of Tuymans is

rich at many levels, particularly the conceptual level.

Despite a calm and esthetically pleasing appearance,

his paintings always hide a deeper level of meaning

which challenges us to go beyond pattern recognition

and machine vision in order to integrate meaning and

understanding. Because meaning and understanding

are still open problems for AI, this project is therefore

interesting because it helps to push forward AI be-

yond the current state of the art, which is all too often

focusing on surface characterics of human experience

rather than meaning and understanding.

2 FORM AND MEANING

The famous art historian and semiotician Ervin Panof-

sky identified five levels in the appreciation of art

works, going from form to meaning (Panofsky, 1972).

These same levels can also be distinguished when per-

ceiving and interpreting every-day activities or im-

ages which are not art, and so results of the present

investigation have a wide applicability beyond the art

context.

Each of Panofsky’s levels has already been studied

in depth using AI methods, although as we move from

form to meaning, results are becoming harder to ob-

tain. Moreover there is clearly a tight interaction be-

tween the levels, requiring a bottom-up and top-down

flow of information, which is often not yet adequately

handled by AI architectures.

1. At the bottom level we focus on the formal ap-

pearance of an art work: the colors, lines, and vol-

umes that are perceived by low-level visual processes

and aggregated into coherent segments. These pro-

cesses have been studied intensely in AI (specifically

the fields of pattern recognition and computer vision)

during the past decades, either by designing and im-

plementing feature extractors and pattern detectors

or, more recently, by using some variant of convo-

lutional networks acquiring features and patterns di-

rectly from data (Cetinica et al., 2018). There are

now many libraries of ready-made low-level visual

processing components available and we have already

applied some of them to the paintings in the Tuymans

collection (occasionally after first training the neural

networks involved).

The results we have obtained so far are often quite

unexpected because paintings are not the same as the

kind of pictures with which pattern recognition algo-

rithms are usually trained. Often the original source

image is deliberately distorted or blurred so that basic

low level vision processing, such as edge detection

or shape from shading, is difficult for existing algo-

rithms.

1110

LTP 385

The Book, 2007

Oil on canvas

306 × 212 cm | 120 ½ × 83 ½ inches

Signed and dated on verso, right: “Luc Tuymans 007”

Pinault Collection

PROVENANCE

Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

Les Revenants, Zeno X Storage, Antwerp, 2007.

Wenn der Frühling kommt, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2008.

La Pelle, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 2019–20.

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

Mapping the Studio: Artisti dalla collezione François Pinault/Artists from

the François Pinault Collection, Punta della Dogana and Palazzo

Grassi, Venice, 2009–11.

MONOGRAPHS AND SOLO EXHIBITION CATALOGUES

Norio Sugawara, Luc Tuymans: Beyond Schwarzheide, ill. 8. Tokyo:

Wako Works of Art, 2007.

Pablo Sigg and Tommy Simoens, ed., Luc Tuymans: Is It Safe?, 126; ill.

72. London: Phaidon, 2010.

Patrizia Dander and Donna Wingate, ed., Luc Tuymans: Wenn der

Frühling kommt, 9, 16; ill. 16. Ed. cat. Haus der Kunst, Munich,

2008. Antwerp: Ludion, 2014.

Frank Demaegd, ed., Luc Tuymans: Zeno X Gallery, 25 Years of

Collaboration, ill. 119, 124, 269. Exh. cat. Antwerp: Zeno X Books,

2016.

SELECTED BOOKS AND GROUP EXHIBITION CATALOGUES

Francesco Bonami and Alison M. Gingeras, ed., Mapping the Studio:

Artisti dalla collezione François Pinault/Artists from the François

Pinault Collection/Artistes de la collection de François Pinault, ill.

272–73. Exh. cat. Venice: Palazzo Grassi; Milan: Mondadori Electa,

2009.

SELECTED LITERATURE

Danny Ilegems, “‘Mijn schilderijen zijn geen schilderijen’: Interview

kunstenaar Luc Tuymans.” Vrij Nederland, May 2007, 70, ill. 70.

Hans Theys, “Van oude spoken en dingen die niet voorbijgaan.” H Art,

May 2007, 3.

Dorine Esser, “‘Ik slaag er niet in iets vrolijks te schilderen.’” Isel, May/

June 2007, ill. 27.

Michele Robecchi, “Luc Tuymans.” Flash Art, October 2007, 130–32.

Yasmine Van Pee, “Unnatural Resources: Luc Tuymans on Fighting the

Literal and Mistrusting Images.” Modern Painters, October 2007,

ill. 75.

Jan Koenot, “De macht van de jezuïeten en de onmacht van beelden:

Terugblik op Luc Tuymans’ serie ‘Les Revenants.’” Streven,

November 2007, 874; ill. 875.

Cornelia Gockel, “Luc Tuymans: Wenn der Frühling kommt.”

Kunstforum International, May–July 2008, 359.

Heinz-Norbert Jocks, “Das Auauchende und das Verschwindende:

Ein Gespräch mit Heinz-Norbert Jocks.” Kunstforum International,

January–February 2019, ill. 194.

NOTES

Part of the group Les Revenants.

Figure 1: Left: ‘The Book’ by Luc Tuymans, oil on canvas

306 X 212 cm, 2017, Pinault Collection. Right: Source

object of this picture, the interior of the Chiesa del Ges

`

u in

Rome. The painting is based on two pages in a book which

contain an image of the church and you see the fold line in

the middle.

Compare for example the Tuymans painting shown in

Fig. 1, left and a photographic picture of the same

scene in Fig. 1 on the right. The painting actually de-

picts a book opened at a picture of the church. The

distortion due to the folding of the pages of the book

and the blurring of lines and surfaces makes low-level

visual processing and image recognition challenging

for humans and even harder for machines. For ex-

ample, standard edge detection and segmentation al-

gorithms are led astray here by the fold mark in the

middle, which is unrelated to the image of the church

and cuts across the whole image.

ICAART 2020 - 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

896

2. On the second level there is the recognition of the

objects and events that are being depicted in the im-

age: the face of a person, a church interior, the pic-

ture of a clown carrying balloons. Panofsky calls this

level the first stage of meaning, specifically the fac-

tual meaning. For example, the colors, patches of

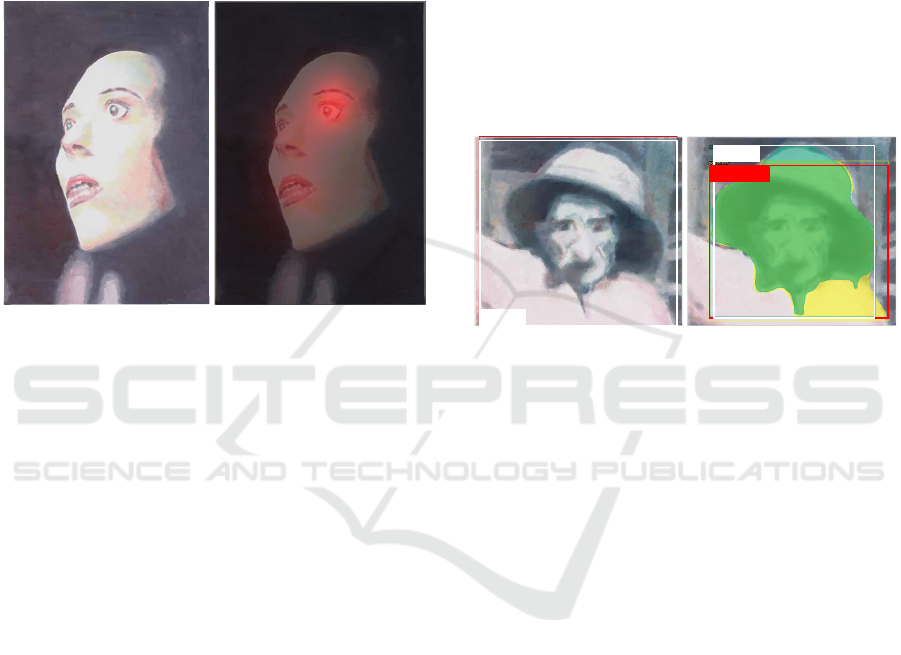

light and dark, and the shapes in Fig.2(left) quickly

assemble in our perceptual field into the face of a

woman.

325324

LTP 538

Twenty Seventeen, 2017

Oil on canvas

94.7 × 62.7 cm | 37 ¼ × 24 ¾ inches

Signed and dated on verso, top right: “L Tuymans 0017”

Pinault Collection

PROVENANCE

Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

La Pelle, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 2019–20.

NOTES

The motif of Twenty Seventeen was painted by the artist as a

temporary mural for the exhibition Jiwa, Jakarta Biennale, 2017.

MSI-net

Figure 2: Left: Twenty Seventeen, 2017, oil on canvas 94.7

X 62.7 cm Pinault Collection. It represents the face of a

woman at the moment she learns that she will be put to death

by poisoning. Right: The most salient area according to the

MSI algorithm is overlayed on the painting using red color

- see section 3. of this paper).

We recognize factual meaning based on our abundant

prior visual experiences of the world. This process is

called image recognition in AI research. It is another

area in which there has been considerable progress

lately by training associative neural networks with

millions of labeled segmented images until a network

is obtained that can autonomously segment and label

novel images. There have been several experiments

to apply such image recognition systems to paintings.

But, similar as to low-level visual processing, the re-

sults typically do not quite reach the performance lev-

els compared to what one gets from analyzing every

day photographs or videos with which these networks

have been trained. The miscategorizations of image

recognition algorithms have even become the object

of new art works (Schmitt, 2018).

It is nevertheless very interesting to wonder how

and why algorithmic results deviate from human ex-

pectations. The main reason is that source images

have been blurred, cut out, enlarged or reduced in the

paintings, making them more abstract, timeless, ex-

pressive and therefore iconic.

Surprisingly, the creative interpretation of the

original sources can expose unexpected unconscious

associations. An example from our image recogni-

tion experiments on the Tuymans collection is shown

in Fig. 3. The painting is overlayed with the results of

two state-of-the-art algorithms: the YOLO algorithm

(left) (Redmon et al., 2015) and the Mask R-CNN al-

gorithm (right) (Girshick et al., 2013). The Yolo al-

gorithm labels the segmented person as a dog (with

0.6 certainty) and the Mask R-CNN algorithm labels

the figure as a person (0.6 certainty) but also as a dog

(0.75 certainty). This is at first bizar until we real-

ize Tuymans depicts here a famous Japanese criminal

Issei Sagawa who was a cannibal but managed to es-

cape justice. Although he is not explicitly depicted as

a dog, there are apparently sufficient dog-like features

to push the image recognition algorithms towards this

classification.

YOLO Mask(R-CNN

0.60(dog

0.75(dog

0.60(person

Figure 3: ‘Issei Sagawa’ by Luc Tuymans, 2014. Oil on

canvas 74,3 x 81,9 cm. Tate collection. The application

of the YOLO image recognition algorithm is shown on the

left and of the Mask R-CNN algorithm on the right. Both

algorithms assign the label dog to this human figure.

3. At the next layer, human observers interpret ob-

jects and events in terms of psychological nuances,

such as emotional states of the persons depicted or

the nature of the actions they carry out (aggressive,

friendly). Panofsky calls this the expressional mean-

ing of an art work. For example, a human viewer rec-

ognizes immediately in the painting in Fig. 2 that this

depicts not just the face of a woman, but a woman

who is very surprised or shocked, maybe by some-

thing that she sees or has just heard. She is in distress

and shows anguish.

Detecting expressional meaning using AI is still

more difficult than object recognition. There has been

some work on sentiment analysis of visual images

(You et al., 2015) but this has not at all reached the

depth with which humans are able to grasp expressive

meaning.

4. The fourth level of interpretation requires un-

derstanding who or what is depicted in order to un-

derstand the motivations and intentions of those be-

ing represented, or the situations in which they find

themselvwes. For example, Fig. 1 is an image of an

image in a book of a baroque church interior, namely

the Chiesa del Ges

`

u, the mother church of the Jesuits

in Rome. The woman in Fig. 2 is a character from

Perceiving the Focal Point of a Painting with AI: Case Studies on Works of Luc Tuymans

897

1312

LTP 386

The Valley, 2007

Oil on canvas

106.5 × 109.5 cm | 41 ⅞ × 43 ⅛ inches

Signed and dated on verso, top right: “Luc Tuymans 007”

Pinault Collection

PROVENANCE

Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

Les Revenants, Zeno X Storage, Antwerp, 2007.

Wenn der Frühling kommt, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2008.

La Pelle, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 2019–20.

MONOGRAPHS AND SOLO EXHIBITION CATALOGUES

Norio Sugawara, Luc Tuymans: Beyond Schwarzheide, ill. iii. Tokyo:

Wako Works of Art, 2007.

Pablo Sigg and Tommy Simoens, ed., Luc Tuymans: Is It Safe?, 69,

127–28; cover, ill. 71. London: Phaidon, 2010.

Patrizia Dander and Donna Wingate, ed., Luc Tuymans: Wenn der

Frühling kommt, 9, 14; ill. 14. Ed. cat. Haus der Kunst, Munich,

2008. Antwerp: Ludion, 2014.

Frank Demaegd, ed., Luc Tuymans: Zeno X Gallery, 25 Years of

Collaboration, ill. 117, 124, 269. Exh. cat. Antwerp: Zeno X Books,

2016.

SELECTED LITERATURE

Hanno Rauterberg, “Schwach gemalt, schwach gedacht.” Die Zeit,

April 24, 2003.

Eric Rinckhout, “Tuymans schildert de macht der jezuïeten.” De

Morgen, April 21, 2007.

Frank Heirman, “Uitverkocht voor opening.” Gazet van Antwerpen,

April 25, 2007.

Jan Van Hove, “De jezuïetenstreken van Luc Tuymans.” De Standaard,

April 25, 2007.

Wim Daneels, “De jezuïetenstreken van Luc Tuymans.” Het Nieuwsblad,

April 26, 2007.

Peter van Dyck, “Luc Tuymans: De duurste Belg.” Gentleman,

April 2007, ill. 52.

Hans Theys, “Van oude spoken en dingen die niet voorbijgaan.”

H Art, May 2007, 3.

Dorine Esser, “‘Ik slaag er niet in iets vrolijks te schilderen.’” Isel,

May/June 2007, 25; ill. 25.

Jeroen Laureyns, “Geschilderde geruchten.” Knack, June 6, 2007.

Jan Koenot, “De macht van de jezuïeten en de onmacht van beelden:

Terugblik op Luc Tuymans’ serie ‘Les Revenants.’” Streven,

November 2007, 870.

“Luc Tuymans on the Failure of Utopias.” Art World, February/March

2008, ill. 16.

Rüdiger Heinze, “Malen auf des Messers Schneide.” Augsburger

Allgemeine, March 1, 2008.

Swantje Karich, “Wieviel Rätsel braucht die Geschichte?” Frankfurter

Allgemeine Zeitung, March 12, 2008.

Thomas Schönberger, “Leerstellen der Monstrosität.” Spex,

March 2008, ill. 126.

Gesine Borcherdt, “‘Wenn der Frühling kommt’ ist der Titel einer

grossen Werkschau im

Münchner Haus der Kunst.” Monopol, April 2008, 115; ill. 115.

Susanna C. Ott, “Geronnene Erinnerung.” Applaus, April 2008.

Morgan Falconer, “Luc Tuymans: Agent Provocateur.” Art World,

April/May 2008, ill. 43.

Hanno Rauterberg, “Was bedeuten diese Bilder?” Die Zeit, May 8,

2008.

Stefanie de Jonge, “De 7 hoofdzonden volgens Luc Tuymans.” Humo,

February 14, 2011, ill. 128.

Elisabeth Vedrenne, “Le monde mental de Luc Tuymans.”

Connaissance des arts, October 2016, ill. 58.

David Castenfors, “Målar Mästare Tuymans.” Artlover, no. 30, 2016,

ill. 5.

NOTES

Part of the group Les Revenants.

Figure 4: Left: ‘The Valley’ by Luc Tuymans, 2007. Oil

on canvas. 106.5 X 109.5 cm. Pinault Collection. Right:

Source image, a still from the Film ’The Valley of the

damned’ directed by Wolf Rilla, 1960. Blurring or lack

of contrast makes low-level image processing and image

recognition very challenging.

a Brazilian dystopian Netflix series called 3 % where

only few people can get to an offshore heaven-like is-

land, where the elite lives, by winning in a game. But

if they lose the game they are killed. This woman just

heard that she lost and will die by poisoning, hence

the expression of shock and dispair. The boy depicted

in Fig. 4 is from a 1960s movie based on the book

’Village of the damned’ by John Wyndham. It is an-

other dystopian story: “All the residents of the village

of Midwich become suddenly unconscious for several

hours. Months later, twelve local women and girls

give birth the same day to albino children with phos-

phorescent eyes. Precocious and able to communi-

cate by telepathy they will quickly reveal hostile in-

tentions.” (Donnadieu, 2019) The boy shown in the

painting is one of these children.

Panofsky calls this the level of conventional mean-

ing because it rests on knowing conventions in society

and knowing about historical events, well known fig-

ures, and cultural artefacts, like books or films. This

kind of meaning is imposed on the image by calling

on episodic and semantic memory or consulting ex-

ternal knowledge sources such as found on the web.

The AI methods that now come into play are based

on knowledge representation, reasoning, and seman-

tic memory, such as knowledge graphs that store vast

amounts of facts (more than 7 billion for the Google

knowledge graph). No efforts have been made so far

to model interpretation of conventional meanings in

paintings using AI, but it is not excluded to start tack-

ling this issue with current semantic technologies.

5. Finally there is the highest layer which Panof-

sky calls the intrinsic meaning or content of an art

work. Here we address the ultimate motives of the

artist, which could be political, psychological, histor-

ical, or mere story telling.

For example, the paintings shown in Figures

1 and 4 are both coming from an exhibition Les

Revenants about the enduring influence of religious

power, against which the painter wants to rebel, in

particular the influence of the Jesuits. The link to the

Jesuits is straightforward for Fig.1 because it depicts

a Jesuit church. The intrinsic meaning is established

by the distortion and the choice of “yellow, earthy and

greyish white, slightly fuzzy hues, (...) which disrupts

the splendor and magnificence of the place. In so

doing, Luc Tuymans inverts the illusionist character

of religious architecture by blurring the sculpted and

painted representations meant to inspire the faithful

and strengthen their faith.” (Donnadieu, 2019).

And even though the boy in Fig. 4 comes from a

totally different context, namely the movie ‘The Val-

ley of the damned’, it still makes a link to the Jesuits.

“The stern, stubborn gaze of the portrayed child, his

strict haircut and clothes signal harsh educational and

social norms or quasi-military upbringing.” (Don-

nadieu, 2019). This is indirectly associated with the

Jesuit educational system that wanted to form ‘sol-

diers of Christ’.

In general, the intrinsic meanings conjured up by

Tuymans create feelings of uneasiness and fear by

referring to antagonistic themes, such as the Nazi

regime, racism, child abuse, religious power, crime,

etc., and it is achieved by the selection of source im-

ages, the very constrained use of colors, image dis-

tortions, and close-ups. For example, the face in

Fig. 2 is actually the projection of a face on a doll’s

head, in order to evoke a feeling of alienation and

dystopia. Building AI systems that can handle this

level of meaning is currently totally beyond the state

of the art. Indeed, the more we get to the level of

intrinsic meaning, the more helpless current AI tech-

niques become.

The different processes going from form to mean-

ing through these five levels are not only supported by

the visual aspects of the work which, partially uncon-

sciously, affect the psychological state of the viewer.

But the title of each work and the explanations in the

catalog are also important factors that influence mean-

ing making. The painting shown in Fig.4 is called

‘The Valley’ giving a clue about the source of this

image, namely a movie with the same name. The

painting in Fig.1 is called ‘The book’, thus giving an

important cue that we are looking at an image of a

book, whereas at first one sees a scrambled interior of

a church. The title ‘twentyseventeen’ (Fig.2) refers to

the year 2017 in which the painting (and the movie)

were made. It is a dark year according to Tuymans

with the rise of populism, Brexit, and disinformation

on social media through companies like Cambridge

Analytica, so that fear and dystopia are appropriate

themes to be evoked in that year.

ICAART 2020 - 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

898

3 THE FOCAL POINT IN

PAINTING

We now zoom in on one of the painterly devices that

shape the perception and interpretation of an art work

and is unique to painting, namely the presence of a

focal point, also known as the entry point or breaking

point. “The focal point of a painting is an area of em-

phasis that demands the most attention and to which

the viewer’s eye is drawn, pulling it into the painting.”

(Marder, 2019) The focal point is not accidental. It

is deliberately chosen by the painter in order to help

achieve intended meanings and it partially shapes the

visual experience of the viewer. There can be a few

focal points in a single painting (rarely more than

3). Abstract paintings, which do not convey mean-

ing (such as by Jackson Pollock for example) might

have no focal point at all.

Modeling how AI systems can recognize the fo-

cal point is an interesting, although very challenging,

case study because it involves in principle all levels

of interpretation. Painters use a diverse set of artis-

tic means to guide viewers: Lines, shapes, color dif-

ferences (in hue, value (brightness) and saturation),

textures, space, and composition, as well as title, ex-

hibition context, and narratives found in the catalog.

The first step is to understand the role of natural

perceptual processes, of which one example is the de-

tection of the most salient areas in a painting. We

have therefore concentrated on this process in a first

preliminary study, using state-of-the-art saliency es-

timation algorithms from the computer vision litera-

ture, which contains hundreds of proposals for this

task. Our goal is not to develop new algorithms nor

to train algorithms with new data, but to see how the

best state-of-the-art saliency algorithms and models

identify as salient in the Tuymans paintings.

The algorithms we applied fall in two classes:

• Knowledge-free saliency estimation exploits gen-

eral properties of the visual image but does not

take into account statistical features learned from

prior visual experiences nor higher-level semantic

features. It is typical for earlier work in pattern-

recognition. No training is needed to apply these

methods. We have tried two state-of-the-art algo-

rithms on the Tuymans collection:

1. The Spectral Residue Based Method (SRB)

(Hou and Zhang, 2007) which analyzes the log-

spectrum of the image to extract the spectral

residue and computes a saliency map on that

basis.

2. The Fine-Grained Method (Montabone and

Soto, 2010) which is based color constancy

detection and pair callibration, segmentation

based on depth continuity, and visual saliency

based on extracted features. The method is spe-

cialized in recognizing humans.

• Knowledge-based Saliency Estimation uses neu-

ral networks that have been trained using super-

vised (deep) learning. We have tried two state-of-

the-art algorithms:

1. POOLNET does salient object detection (not

just region detection) and gives no result when

an object could not be detected (Liu et al.,

2019). It uses a convolutional neural network

with additional components for combining low-

level (close to the visual form) and high-level

(semantic) features with results from other vi-

sual processes such as edge detection. POOL-

NET is trained on a corpus of real world images

of which the salient regions have been anno-

tated by human observers.

2. MSI-Net (Kroner et al., 2019) uses a combi-

nation of encoder-decoder convolutional neural

networks at several levels of granularity. It has

been pre-trained with human eye-tracking data

on a very large corpus of natural images, but

not paintings.

We found that the MSI algorithm works best as an

approximation of what human users find the most

salient area in the Tuymans’ paintings, and this in

turn is often, but not always, a strong cue of the focal

point. The result for the painting ‘Twentyseventeen’

is shown in Fig. 2. It is the face of a woman and the

most salient area is the right eye (from our perspec-

tive), turned towards the viewer. It is clearly the focal

area of the painting. There is a slight secondary focus

on the lips.

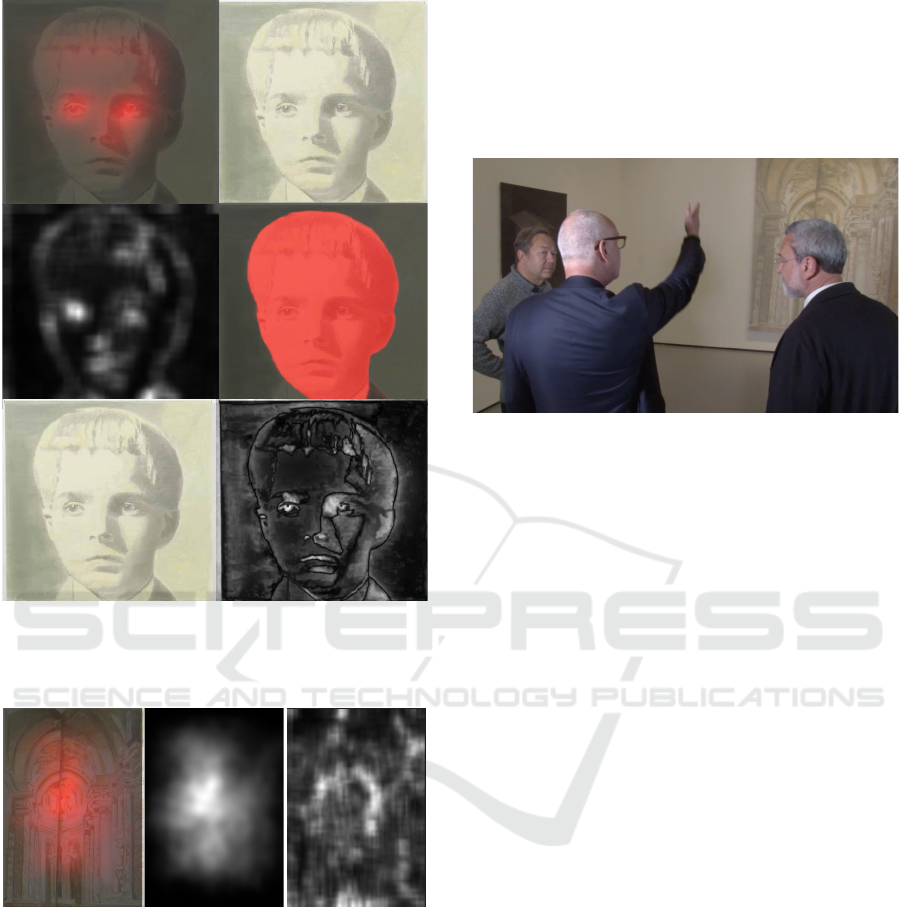

Fig.5 shows the application of different algorithms

on ‘The Valley’ shown in Fig.4. MSI-net (left top)

gives the best results focusing on the eyes as primary

salient region, and on the top hairline as secondary

area, emphasizing the unusually big forehead of the

boy. POOLNET shows the whole object and is there-

fore less interesting with respect to identifying the

focal area. SRB shows several regions so that it is

less relevant for finding the most salient one and Fine-

Grained shows edges instead of regions.

Finally, Fig.6 shows the applications of the

salience estimation algorithms for ‘The book’ (Fig.1).

We see that both MSI and Fine-Grained detect a

salient area in the middle of the painting, which is

also concordant with our human experience. It draws

attention to the fold mark (which is confirmed by

comments in the Palazzo Grassi catalog (Donnadieu,

2019)). However, interestingly enough, when the

Perceiving the Focal Point of a Painting with AI: Case Studies on Works of Luc Tuymans

899

Figure 5: Application of different algorithms to detect

saliency for the painting shown in Fig. 4. From left to right

and top to bottom, we used 1. MSI-net. 2. Source image, 3.

SRB, 4. POOLNET, 5. Source-Image, 6. Fine-grained.

Figure 6: Saliency detection using various algorithms on

‘The book’ shown in Fig. 1. From left to right. 1. MSI-net.

2. Fine-grained. 3. SRB. POOLNET gives no results at all

because no object could be detected.

painter Luc Tuymans was shown this result, he re-

marked that there is actually another focal point.

Indeed, when your gaze follows the vertical line

of the fold (see Fig. 1), it ends up at the top edge

of the painting. In that region it becomes suddenly

clearer that these are the pages of an open book, and

that the vertical line is a fold mark. In fact, if one

looks more carefully one sees that the pages on the

top of the vertical line are slightly curled, presumably

to draw further attention to the fact that we are dealing

with an opened book (see Fig.7). This shows the de-

gree of sophistication with which Tuymans attempt to

manipulate the viewer’s gaze and the enormous chal-

lenge to build AI systems that are sensitive to these

art-making strategies, let alone use themselves these

strategies to create new art works.

Figure 7: Tuymans (middle) discusses the importance of the

vertical line in the painting ’The Book’ (Fig. 1), seen here

in the background. The pictures has been taken during con-

versations at the Palazzo Grassi in september 2019 with Luc

Steels (shown to the left) and Massimo Warglien (shown to

the right). This image illustrates the large, almost human-

sized, height of the painting, emphasizing the monumental

character of the church.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has sketched different levels of percep-

tion and interpretation for art works, more specifically

paintings, referring to the earlier influential writings

of Panofsky. Using AI methods, we can unpack these

levels and try to build very precise operational mod-

els in order to shed new light on art, build tutoring

tools for art education, and give a novel instrument to

artists to reflect on their artistic practices, which are

today based on very powerful intuitions and intense

creativity but not on scientific knowledge. The paper

illustrated this approach with the work of the Flemish

painter Luc Tuymans. We conducted a preliminary in-

vestigation on the perception of the focal point, show-

ing the strength and limitations of salience estimation

methods from computer vision and the need to take

other dimensions (such as color usage or the implicit

lines in a painting) as well as semantic issues (such as

triggered by the title or the catalogue) into account.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was made possible by the art-science

initiative of the H2020 FET Proactive project Ody-

cceus with the Ca’Foscari University of Venice as a

ICAART 2020 - 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

900

partner, the Scientist in Residency project of ‘Luc

Steels in Studio Luc Tuymans’ as part of the EU

H2020 Regional STARTS Center at the Centre for

Fine Arts (BOZAR) in Brussels, and the EU H2020

Humane AI Flagship preparation project of which

IBE (UPF/CSIC) in Barcelona is a partner. This paper

was influenced by a conversation between Luc Steels

and Luc Tuymans at BOZAR in Brussels on 6 novem-

ber 2019. This conversation was a collateral event of

BNAIC, Belgian-Dutch AI conference. The help of

Bram Bots and Isadora Callens of Studio Luc Tuy-

mans in Antwerp for the provisioning of data is grate-

fully acknowledged as well as the help of Christophe

De Jaeghere, Lise Ninane and Emma Dumartheray of

the Gluon Foundation in Brussels for facilitating this

art-science collaboration. The paper was stimulated

by a presentation by LS at the Computer and Art sym-

posium at ECLT, Ca’Foscari University of Venice,

October 2019. LS has been responsible for the re-

search direction and the writing of the paper and BW

has performed technical research into the algorithms

and carried out the experiments. Conversations with

Massimo Warglien from the Ca’Foscari University of

Venice as well as the time and ideas generously pro-

vided by Luc Tuymans are gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

Cetinica, E., Lipica, T., and Grgicb, S. (2018). Fine-tuning

convolutional neural networks for fine art classifica-

tion. Expert systems with applications, 114:107–118.

de Boer, V., Wielemaker, J., van Gent, J., Oosterbroek,

M., Hildebrand, M., Isaac, A., van Ossenbruggen, J.,

and Schreiber, G. (2013). Amsterdam museum linked

open data. Semantic Web, 4(3):237–243.

Donnadieu, M. (2019). La Pelle, exhibition guide. Palazzo

Grassi, Venice.

Garcia, N. and Vogiatzis, G. (2018). How to read paint-

ings: Semantic art understanding with multi-modal re-

trieval. In Proceedings of the 2018 European Confer-

ence on Computer Vision (ECCV). Computer Vision

Foundation.

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T., and Malik, J. (2013).

Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection

and semantic segmentation.

Hou, X. and Zhang, L. (2007). Saliency detection: A spec-

tral residual approach. In 2007 IEEE Conference on

Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE.

Kroner, A., Senden, M., Driessens, K., and Goebel, R.

(2019). Contextual encoder-decoder network for vi-

sual saliency prediction. CoRR, abs/1902.06634.

Liu, J., Hou, Q., Cheng, M., Feng, J., and Jiang, J. (2019). A

simple pooling-based design for real-time salient ob-

ject detection. CoRR, abs/1904.09569.

Marder, L. (2019). Why focal points in paint-

ings are so important. liveaboutdotcom,

”https://www.liveabout.com/all-about-focal-points-

in-painting-4092634”(2019).

Meyer-Hermann, E. (2019). Catalogue Raisonn

´

e of Paint-

ings. David Zwirner Books, Yale University Press,

New Haven.

Montabone, S. and Soto, A. (2010). Human detection us-

ing a mobile platformand novel features derived from

a visualsaliency mechanism. Image and Vision Com-

puting, 28(3):391–402.

Panofsky, E. (1939,1972). Studies in Iconology. Humanistic

themes in the art of the Renaissance. Oxford Univer-

sity Press, Oxford.

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., and Farhadi, A.

(2015). You only look once: Unified, real-time ob-

ject detection.

Schmitt, P. (2018). A computer walks into a gallery. In

ICCV Computer Vision Art Gallery. Computer Vision

Foundation.

Semmo, A., Isenberg, T., and Doellner, J. (2017). Neural

style transfer: A paradigm shift for image-based artis-

tic rendering? In Proceedings of the Symposium on

Non-Photorealistic Animation and Rendering. ACM.

Strezoski, G. and Worring, M. (2017). Omniart: Multi-

task deep learning for artistic data analysis. CoRR,

abs/1708.00684.

Tuymans, L. (2018). The Image Revisited. In conversation

with G. Boehm, T. Clark and H. De Wolf. Ludion,

Brussels.

You, Q., Luo, J., Jin, H., and Yang, J. (2015). Robust image

sentiment analysis using progressively trained and do-

main transferred deep networks. In Proceedings of the

29th AAAI Conference. AAAI.

Perceiving the Focal Point of a Painting with AI: Case Studies on Works of Luc Tuymans

901