I Learn. You Learn. We Learn? An Experiment in Collaborative

Concept Mapping

Claudia Picardi

1

, Anna Goy

1

, Daniele Gunetti

1

, Giovanna Petrone

1

, Marco Roberti

1

and Walter Nuninger

2

1

Dipartimento di Informatica, Universit

`

a degli Studi di Torino, Torino, Italy

2

Universit

´

e de Lille, Lille, France

Keywords:

Learning, Concept Map, Perspective, Collaboration.

Abstract:

In this paper we present an experiment on digitally-supported collaborative Concept Maps focused on asyn-

chronous and remote collaboration. We investigated the integration of multiple perspectives on the same topic,

providing users with a tool allowing an individual perspective for each user plus a shared one for the group.

Several user actions were made available, affecting one or both perspectives, depending on the context. Re-

sults show that integrating different perspectives in a way that everyone can relate to is indeed a complex task:

users need to be supported not only in the production of a shared Concept Map, but also in the process of

adapting their mental representations, in order to understand, compare and possibly integrate others’ points

of view. Our experiment shows that both collaboration in concept mapping (emphasis on the process) and

collaboration on a Concept Map (emphasis on the result) are needed, whereas most tools, including the one

we experimented with, focus on the latter. The main challenge is allowing people to understand, compare and

assess each other’s map, recognizing commonalities and differences through different representation styles

and spatial organizations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Small-group collaboration among peers is a well

recognized way to promote the acquisition of new

concepts in many different learning environments

(Hertz-Lazarowitz et al., 2013; Johnson and Johnson,

2013; Johnson et al., 2000; Luff and Heath, 1998).

The mechanisms that underlie positive learning out-

comes have been investigated in depth (Roscoe and

Chi, 2007; Webb and Mastergeorge, 2003), and all of

them involve different forms of “Information Process-

ing”, where new knowledge is generated by connect-

ing together old and new pieces of information, and

by building new or different relationships between in-

formation already owned (Webb, 2013). In a col-

laborative setting, learning implies that part of the in-

formation and of the relationships among pieces of

information comes from different individuals. Every-

one involved in the learning process is therefore called

to contribute to build up a shared view of the overall

knowledge, while at the same time retaining a per-

sonal view of the learned concepts. This in turn con-

tributes to the development of collective and social

intelligence (Brackett et al., 2011; Meza et al., 2018).

As a consequence, personal views can differ even

substantially from the shared one, and, apart from the

new knowledge acquired on the studied subject, ev-

eryone involved in the process can learn that: i) there

may be different perspectives from one’s own, and

even conflicting with it; ii) each perspective may pro-

vide different insights on the subject under study; iii)

one can learn something from others’ perspective.

Concept Maps are one of the most known and

widespread tools to represent, communicate, share

and acquire new knowledge, in a variety of branches

of education (Ca

˜

nas et al., 2015; Khine et al., 2019;

Novak, 2010; Romero Garc

´

ıa et al., 2017). In a tra-

ditional setting, Concept Maps are used by either in-

dividual students or small groups of learners gather-

ing together, often under the supervision of a teacher.

The benefits of team work based on Concept Maps, as

a part of problem solving approaches, have been in-

vestigated by several authors (Haugwitz et al., 2010;

Kandiko et al., 2013).

Nowadays computer and network technologies al-

low Concept Maps to be represented digitally, and

promote remote and asynchronous collaboration. Per-

sonal Learning Environments (PLE) (Attwell, 2007;

Picardi, C., Goy, A., Gunetti, D., Petrone, G., Roberti, M. and Nuninger, W.

I Learn. You Learn. We Learn? An Experiment in Collaborative Concept Mapping.

DOI: 10.5220/0009321300150025

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 2, pages 15-25

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

15

Wilson et al., 2007) are emerging, allowing learn-

ers to build their own learning workspaces. PLEs

often enable users to integrate shared and personal

workspaces, although the definition of models sup-

porting these features, while offering a high level of

free-decision making, is still an open issue (H

¨

akkinen

and H

¨

am

¨

al

¨

ainen, 2012).

Several digital tools for concept mapping exist

that also allow for some type of cooperation among

multiple authors. Many collaborative web applica-

tions for graph design include Concept Maps among

their templates and stencils (see e.g. Lucidchart, Cre-

ately or Draw.io, to name a few), and CmapTools

(Ca

˜

nas et al., 2004), arguably the most complete tool

for Concept Maps, also provides teamwork support.

Collaboration support in these applications ranges

from merely enabling the concurrent editing of a same

map by multiple authors, to more refined mechanisms

for proposal, discussion, and acceptance or rebuttal of

changes and additions to the collaborative map. Col-

laboration thus revolves around reaching a common

understanding or presentation of a topic.

However, the effectiveness of collaboration in

learning relies also on the participants gaining aware-

ness of their different perspectives. Participants are

encouraged to compare their points of view, to rec-

ognize both common ground and differences; from

this process they can acquire not only a wider and

deeper knowledge of the study subject, but also meta-

knowledge on what is peculiar of their own under-

standing, as is common in competency-based peda-

gogical approaches, especially learn-by-teaching (see

e.g. work by Grzega and Sch

¨

oner (2008) and by

Sedelmaier and Landes (2015))

The aim of our research is thus to further refine

collaborative mechanisms by incorporating the notion

of perspective within the Concept Map model, so that

several personal perspectives (one for each author)

can coexist with a shared perspective (common to the

whole team of learners). As we will see in the next

section, the fact that they are perspectives, and not

just different “versions” of the same Concept Map,

means that the personal perspective of each author is

related to the shared team perspective. Actions per-

formed on one of the two perspectives may affect the

other as well.

The goal of our experiment is to study a learn-

ing process where each author can develop both per-

spectives together, contributing to the shared perspec-

tive with the insights and understanding gained from

her/his personal work, while at the same time en-

riching her/his individual perspective thanks to what

emerges during the collaboration. Within this con-

text we can envisage two teamwork learning scenarios

(actually, two extremes of a broad spectrum of learn-

ing activities that can be proposed):

1. collaboratively build a shared perspective of a

given topic and, thanks to such collaborative pro-

cess, develop an individual perspective, or

2. first represent one’s own personal perspective, and

subsequently use it as a contribution to a collab-

orative activity, where a shared perspective is de-

veloped starting from individual work.

In a previous work (Goy et al., 2017) we focused

on the first scenario mentioned above, and report an

in-lab evaluation of the first version of our proto-

type, Perspec-Map. In the experimental setting small

groups of learners were asked to collaborate in or-

der to build a Concept Map expressing knowledge

shared by all the people belonging to the same group.

Nonetheless, each volunteer was allowed to build a

private map, i.e., a personal perspective, which es-

sentially grew out of the shared one whenever there

was a disagreement with respect to the shared map.

To perform our experiments we developed a proof-

of-concept prototype which enabled users to see and

interact both with the shared and with the personal

perspective, that were presented in separate panels on

the screen. All participants were allowed to update

the shared perspective, while a personal perspective

could only be updated by her owner.

In a subsequent work (Nuninger et al., 2018) we

report the evaluation of a second version of the pro-

totype in a real world setting, namely, the Automatic

Control class at Polytech’Lille, in a Continuous Vo-

cational Training for Chartered Engineers. Thanks to

this experience, we realized that the role of multiple-

perspective Concept Maps could be much broader

than the one devised initially. As we then stated

(Nuninger et al., 2018), “the goal in collaboration is

not to reach exactly the same perspective for all par-

ticipants, but rather to help each other reaching a per-

sonal understanding of the topic under consideration”.

Outcomes of our both experiments on scenario 1

can be summarized as follows. As instructed, partic-

ipants tended to concentrate on building the shared

perspective, while the personal one was mainly per-

ceived as a repository of elements and/or as a place

to sketch concepts to be later shared with the others.

The personal perspective was seldom perceived as an

alternative point of view w.r.t. the shared map, but

rather used to compare it to the work done together

to see if personal work had been kept or removed

by other participants. Broadly speaking, participants

found it difficult to fill the gap between the shared

and the personal perspective. For most users it turned

out hard to read and understand the map fragments

provided by others: in most cases, they just added

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

16

their map fragment to what already present, in some

cases restating with different wording what already

expressed by others.

All in all this is consistent with what found by

Smit (1989) and Shea (1995): learners do not tend

spontaneously to aggregate and collaborate with the

aim of learning something new: new knowledge, new

points of view, new perspectives. Working collabora-

tively to build new pieces of shared knowledge is per-

ceived as difficult because of many reasons, includ-

ing different understanding of the concepts, different

focus on what is important and what can be over-

looked, different terminology used. A plausible, more

in depth explanation for such difficulties is that, actu-

ally, people often delve into the cooperative learning

process without having in advance a clear personal

understanding of the knowledge they are trying to de-

velop cooperatively. If a piece of knowledge is only

partially or confusedly comprehended, trying to inte-

grate it with others’ point of view of the same issue

will definitely turn out a messy and tiresome process.

Because of the above reasons, one may wonder

whether a collaborative learning process that starts

from a well understood and clearly stated personal

knowledge and moves toward a shared view can be

more successful and user friendly. In fact, this sce-

nario corresponds to the second type of collaborative

learning process described above.

In this paper we illustrate and discuss the outcome

of a series of experiments conducted on a novel pro-

totype (Perspec-Map 2.0) where learners first tackle

their individual perspectives, and only subsequently

engage in team work. In our presentation we fol-

low the guidelines of the Design Science Research

Methodology as introduced by Peffers et al. (2007).

The rest of this paper is thus organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the approach we devised and ex-

perimented with. Section 3 presents the experimen-

tal setting and reports on the results, that is, qualita-

tive observations and questionnaire answers. Section

4 discusses such results, and draw some lessons for

future work. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 MULTI-PERSPECTIVE

CONCEPT MAPS

As our research focuses on collaboration in learning,

it is important to recall that in any type of collabora-

tive work there are two major distinctions, concerning

the place and time of the collaboration (Skaf-Molli

et al., 2007): co-located vs. remote and synchronous

vs. asynchronous collaboration. We can therefore dis-

tinguish four different types of collaborative activity;

each poses different challenges with respect to inter-

action.

In the context we have been concentrating on –

loosely-structured, possibly lifelong, ubiquitous and

generally community-based learning – the collabora-

tion is mostly remote and asynchronous. Therefore,

our research is focused on this type of collaboration,

and our experiments were similarly designed within

this hypothetical scenario.

The interaction model we designed and tested en-

ables users to work in a group with the goal of build-

ing a multi-faceted Concept Map, where multiple per-

spectives are maintained (a personal perspective for

each group member, and a shared one for the group),

focused on a given topic, maintaining conceptual re-

lationships between the two. The goal is in fact to

enhance meta-knowledge, by increasing awareness of

the existence and value of different perspectives, as

well as enabling reasoning on similarities and differ-

ences. A key step is therefore being able to relate

one’s own personal perspective with the shared one,

and compare the two.

As already mentioned, in the proposed approach

the personal and the shared perspective are repre-

sented as two super-imposed layers, with the layer on

top being the “active” one, and the layer on the bot-

tom being visible but not editable. Users can select

which perspective is active by bringing it to front: ele-

ments of the upper, active perspective will appear with

full opacity, in color, while those belonging to the

lower, inactive perspective will be in grayscale and

shaded, as if underneath a partially transparent white

sheet. By changing perspective, users not only choose

what to see on top, but they also choose a work mode,

which will affect the set of available operations, and

the consequences they have on the artifact.

In both cases, standard operations on the Con-

cept Map elements (i.e., nodes and arcs) are enabled,

namely: add (corresponding to the creation of a new

element), remove (corresponding to the elimination of

an existing element), edit (corresponding to the modi-

fication of an element label or a relation connections),

move and resize (corresponding to the adjustment of

visual aspects of the map, like the dimension of nodes

or their position on the canvas).

When performed from the personal perspective,

such operations do not affect the shared one. This im-

plies that from their personal perspective users cannot

actually edit, move or resize those elements that have

been shared, and thus belong to the shared perspec-

tive.

When these operations are performed from the

shared perspective, their effect cascades on the per-

sonal ones; in particular:

I Learn. You Learn. We Learn? An Experiment in Collaborative Concept Mapping

17

• when a user adds an element to the shared per-

spective, it is also added to her personal view;

• when a user deletes an element from the shared

perspective, if it belonged also to her personal

view then it is also deleted from it (while a copy

of the element remains in each personal view that

contained it); it is worth mentioning that, if a user

removes an element belonging to both views from

her personal perspective, the element is not re-

moved from the shared one;

• when a user modifies an element in the shared per-

spective, it is also modified in each personal view

that contains it;

• when a user moves or resizes an element in the

shared perspective, it is also moved/resized in

each personal view that contains it.

Moreover users can share elements from their per-

sonal perspective to the shared one: the effect is that

the element is added to the shared perspective; if the

element is a relation, and the connected nodes do not

belong to the shared view, they are added to it as well.

Finally, a user can import elements from the

shared perspective into her personal one: the effect is

that the element is added to her personal perspective

(if the element is a relation, the import is extended to

the connected nodes).

The Perspec-Map 2.0 tool implementing this in-

teraction model is an Angular-based application, that

makes significant use of the HTML5 Canvas technol-

ogy to represent the multi-perspective map, and is

backed by a lightweight PHP server coupled with a

MySQL database. Its users are grouped in “projects”,

each of them containing a number of maps (called

“map works”). Inside a project, users can participate

to map works, i.e. they can collaborate together to

build shared maps.

A user can edit a map work either in individual or

in collaborative mode. In individual mode, she or he

will be shown her or his personal perspective in the

foreground, with the shared one seen in transparency.

Her or his actions will be understood as being per-

formed from the personal perspective. Conversely, in

collaborative mode the shared perspective will be in

the foreground, and the user’s actions will be inter-

preted accordingly.

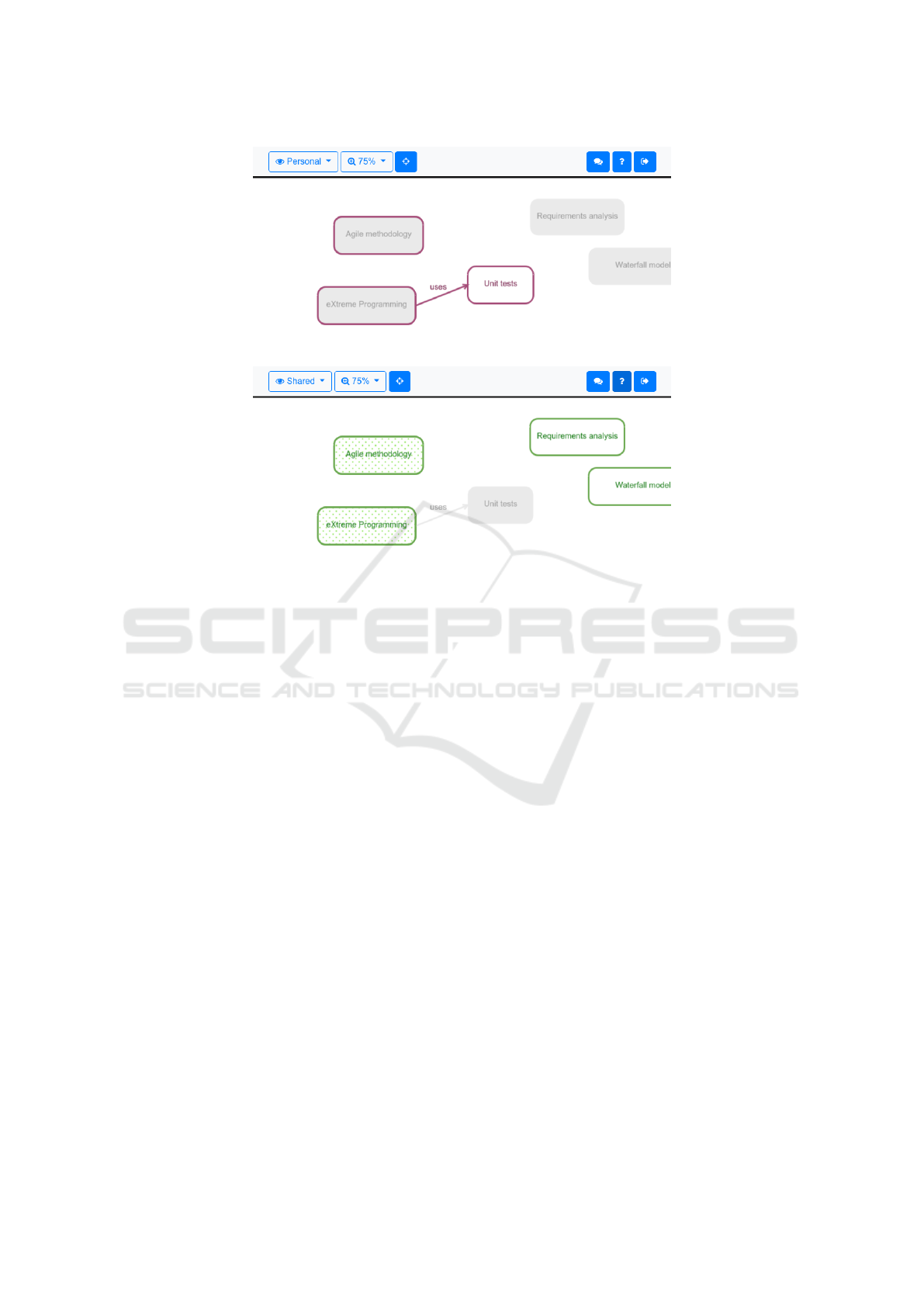

Figure 1 shows the map work user interface: for

each user, her personal perspective and the shared one

overlay; while using it, users can switch anytime from

the personal perspective to the shared one, by bring-

ing to front the perspective they are interested in. The

elements’ color provides a chromatic clue about the

perspective in focus, that is anyway made explicit on

the upper bar.

In the current prototype, the green color scheme

corresponds to the shared perspective: in it, light gray

elements are not interactive, as they belong solely to

the personal layer. Elements that are in both the per-

sonal and the shared view are shown with a dotted

pattern. Furthermore, the personal perspective is as-

sociated to a purple color scheme: like before, light

gray elements are “behind the glass”, while in this

case objects that belong to both perspectives are light

gray, purple edged and uneditable – although they can

still be used as relationship handles.

The mapwork user interface offers all the actions

that are required by the Concept Map paradigm: con-

cept or relationship creation, editing and deletion; sin-

gle and multiple element share or import (depending

on the actual perspective). Moreover, convenience

features, such as map recentering and zooming, are

available.

Finally, for each mapwork the tool provides a mes-

sages board, to allow users to make notes to each

other.

3 EXPERIMENTATION

3.1 Setting

The experiments involved fifteen volunteers recruited

among colleagues, PhD, graduate and undergraduate

students. Ten participants had a background in com-

puter science, two in biology, two in human sciences

and one in economics. Three participants had a PhD,

three a master’s degree, two a master’s degree and the

remaining seven were undergraduate students.

Our experiments were conducted in three steps,

as described below.

Step 1: People were asked to read a six pages

introduction to Software Engineering, describing

basic concepts and a few more in depth details about

the discipline. If needed, a two-page introduction to

Concept Maps was also available. Volunteers had a

few days to read these two documents at their ease.

Step 2: Every individual scheduled a working session

with a member of the supervising team (composed

by the authors of this paper). In this session, using

the prototype described in the previous section, the

volunteer built her personal map of what read in the

document on Software Engineering. The working

session was supervised by one of us, but without any

intervention on the choices made be the individual

while developing her personal map. While super-

vising this work, we discovered that some of them

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

18

(a) Personal perspective on top

(b) Shared perspective on top

Figure 1: The map work user interface in Perspec-Map 2.0. Both screenshot show the same map work. The upper screenshot

(a) shows the map work in individual mode, with the personal perspective on top, highlighted by solid lines, and the shared

perspective grayed out in the background. In the bottom screenshot (b) the situation is reversed: we are in collaborative mode,

thus the shared perspective is on top, highlighted by solid lines, while the personal one is grayed out in the background.

Thus for example the concept “Unit tests” exists only in the personal perspective of this user, while “Agile methodology” and

“eXtreme Programming” exist in both. “Requirements analysis” and “Waterfall model” on the other hand exist only in the

shared perspective. The top bar shows which perspective is active, and the visibility (75%) of the inactive perspective, which

can be brought down to 0 if one only wants to see the active one. Buttons on the right allow users to open the chat, to see the

help page, and to exit from this map work.

had decided to jolt down on paper a first sketch of

the Concept Map they were asked to build in this step.

Step 3: After a few days, experimenters were grouped

in five groups, and the three individuals in each group

were asked to meet in order to build a shared map

of what read in step 1, starting from their personal

maps built in step 2. People in each group worked

together at the same time, but they could communi-

cate between each other only through real time writ-

ten messages. Even in this step, one of us was present

in each session to provide support, again avoiding any

intervention in the development of the shared map.

During this step, each volunteer was allowed to up-

date her personal map on the basis of what was going

on in the development of the shared map.

Every action taken and every message exchanged

in both step 2 and 3 was logged in order to be later an-

alyzed so as to understand how people interacted with

the prototype and between each other while building

their map. Moreover, after the completion of step 3,

volunteers were asked to fill a questionnaire regarding

their experience during the experiments. The ques-

tionnaire was focused on the following:

• the perceived usefulness (toward the learning

goal) of the collaboration tasks we asked them to

perform;

• the perceived ease with which these tasks were

performed in the tool we provided them with;

• their general attitude toward collaboration in con-

cept maps.

Our goal was for the questionnaire to help us under-

stand their subjective point of view, and to distinguish

as much as possible whether the obstacles they en-

countered were due to the tasks themselves or to the

tool they were using.

I Learn. You Learn. We Learn? An Experiment in Collaborative Concept Mapping

19

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Subjects Profiling

All fifteen volunteers declared to frequently use com-

puters for studying. Eleven out of fifteen already

knew Concept Maps (possibly with another name)

and used them; however, only four had an experience

with digitally-supported Concept Maps, whereas the

others had only used paper-based maps.

3.2.2 Usability Assessment

We administered a standard usability questionnaire

1

in order to check the overall usability of the tool, and

to highlight possible usability problems that could af-

fect the results of the Perspec-Map 2.0 functionality

evaluation.

In short, this questionnaire confirmed that the

Perspec-Map 2.0 application was usable enough; in-

teraction difficulties highlighted in our evaluation re-

sults (reported in sections 3.2.3 and 3.2.4) are there-

fore not directly ascribable to standard usability is-

sues. We report here the answers to the most relevant

questions in the following.

Users found the application quite easy to use: On

a 5-point scale, tool usability scored a mean of 3.71

and a median of 4 (1=low usability, 5=high usabil-

ity); tool awkwardness scored a mean of 1.71 and a

median of 1 (1=low awkwardness, 5=high awkward-

ness). Users also judged the tool simple (without un-

necessarily complex features) and quite intuitive (they

would not need special assistance to be able to use it).

Users also found the application usage easy to learn:

tool easiness to learn scored a mean of 3.57 and a

median of 4 (1=difficult to learn, 5=easy to learn);

learning overload scored a mean of 1.36 and a me-

dian of 1 (1=light overload, 5=heavy overload). Users

also found a sufficient degree of functions integration,

evaluated with a mean of 2.93 and a median of 3.

3.2.3 Questionnaire Results

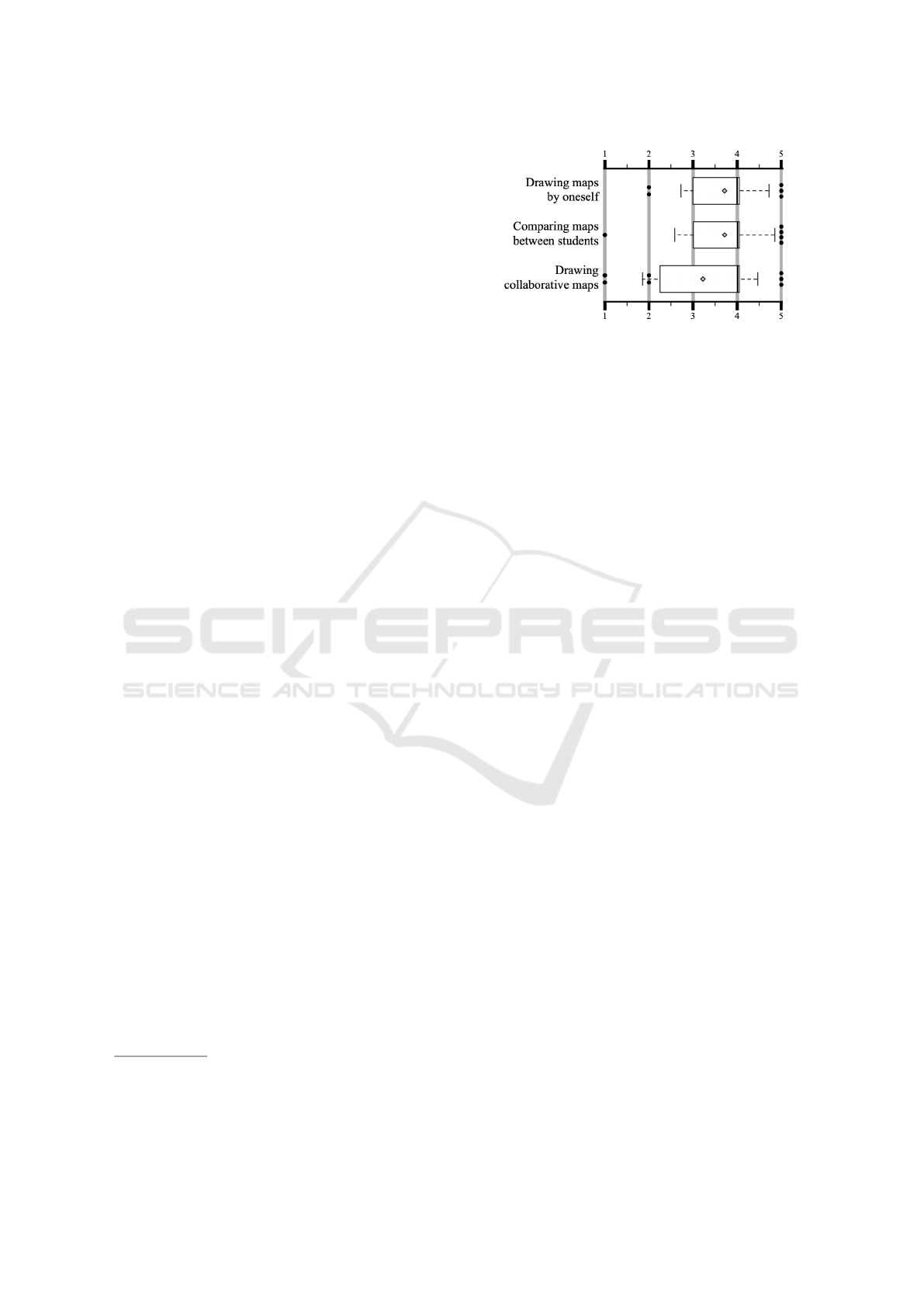

The first question (Figure 2) was aimed at assessing,

on a 5 points scale, the usefulness of Concept Maps

per- , in relation to study, regardless of the specific

tool or application. Drawing solo maps and compar-

ing solo maps are both deemed reasonably useful (av-

erage 3.71, median 4), with a slightly higher variabil-

ity in answer on the latter (one user deems comparing

1

The questionnaire is based on the System Usability

Scale (SUS) developed by John Brooke at Digital Equip-

ment Corporation. (c) Digital Equipment Corporation,

1986.

Figure 2: In your experience, how fruitful are the following

activities when learning a subject?

maps totally useless, while 4 found it highly useful).

Participants were instead divided on the usefulness of

drawing collaborative maps: although the median is

again 4, as for the other two activities, 4 people deem

this activity very little or not at all useful.

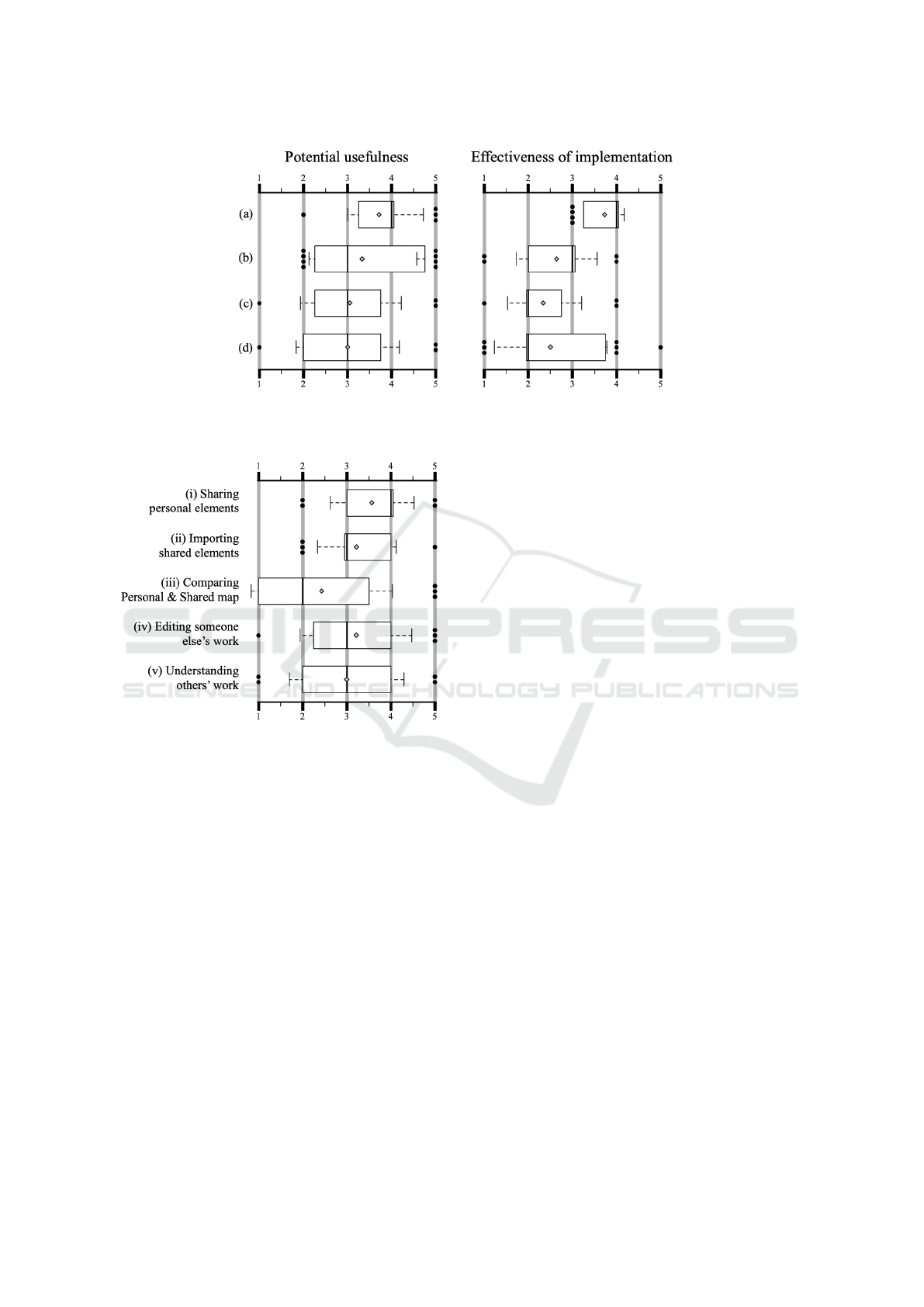

The next set of questions (Figure 3) concerned

more specifically computer-supported map building

and investigated four aspects of the activity the users

had to carry out in our experiment: (a) building a Per-

sonal map, (b) building a Shared map, (c) the exis-

tence and management of common concepts in the

two (Personal and Shared) maps, and (d) the “differ-

ential” representation of the two maps in overlay in

order to highlight commonalities and differences.

It is worth noting that, in this experiment, we were

not interested in evaluating the quality of the shared

map per se (Nuninger, 2015; Nuninger et al., 2018),

but rather the quality and usefulness of different as-

pects of the learning process.

In particular, for each aspect (a) to (d), we asked

our participants to rate both its potential usefulness

when learning a subject, and the effectiveness of its

implementation in our application.

Concerning (a), i.e. building a Personal Map, the

potential usefulness and the effectiveness of the im-

plementation were perceived as good (average 3.71

for the former and 3.86 for the latter, median 4 for

both). This result is also consistent with the perceived

efficacy of building solo maps shown in our first ques-

tion (see Figure 2).

The potential usefulness of aspect (b), i.e. build-

ing a Shared Map, left the participants quite divided.

They however were slightly more positive in this an-

swer, which concerned specifically a computer-aided

activity, than they were on the general task of building

collaborative maps with fellow students in the previ-

ous question (see again Figure 2). On the overall the

implementation of this aspect was however seen as

only partially effective (average 2.64, median 3).

Concerning aspects (c) and (d), they were both

deemed moderately useful to the learning process (av-

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

20

Figure 3: Potential usefulness and effectiveness of current implementation for (a) building a Personal map, (b) building a

Shared map, (c) existence and management of common concepts in the two maps, (d) “differential” representation of the two

maps in overlay.

Figure 4: How easy was each of these tasks on a 5-points

scale?

erage 3, median 3) for both, with a moderately high

variability in answers. The implementation of (c) was

perceived as not very effective (average 2.36, median

2) quite consistently by most participants. The imple-

mentation of (d) presents similar aggregated results

(average 2.5, median 2) but more variable answers,

with 9 answers in the “low” range (scores 1 and 2), 4

in the “high” range (scores 4 and 5), and 2 with the

intermediate score of 3.

Next we asked our participants to evaluate the ease

of the different collaboration tasks. Figure 4 shows

the results: tasks (i), (ii) and (iv) were rated moder-

ately to very easy by at least two thirds of the partici-

pants (average 3.57 and median 4 for (i), average and

median 3 for (ii) and (iv)).

Since our experiment revolved around collabora-

tion, we also inquired about how and if the Personal

map turned out to be useful during the collaboration.

All participants said that the Personal map was use-

ful to some degree. 12 people found it useful to com-

pare their perspective, expressed by the Personal map,

with the one expressed by the group in the Shared

map. 9 people found it useful to be able to safe keep

things that others wanted to delete from the Shared

map. Only 2 people used the Personal map to keep

some things private, but most did not see privacy as

an issue in this context.

3.2.4 Qualitative Observations

In the following we summarize the qualitative obser-

vations we collected while users performed the ex-

periments, including explicit comments they voiced

aloud. We organize them in three categories:

• Spatial Organization: comments and observa-

tions concerning the changes in the position of

map elements due to the concurrent editing of the

two overlaid perspectives (personal and shared);

• Seeing and Comparing: comments concerning

the impossibility of seeing others’ personal per-

spectives;

• Verbal Interaction: comments concerning the

availability of tools for verbally explaining one’s

own actions;

Spatial Organization

• “The position of nodes is important in order to

represent concepts”;

• “I am uncomfortable with having my personal

perspective modified when other users change

nodes (their position) in the shared perspective”;

• “It is important to me to keep my own alignment

of nodes” ;

• “The spatial changes in the shared perspective

make my personal one ureadable”;

I Learn. You Learn. We Learn? An Experiment in Collaborative Concept Mapping

21

• “Building a shared perspective was disruptive for

my personal one, conceptually and spatially”;

• “I would like to be able to have nodes in different

positions in the shared and personal perspectives”;

• “When a shared perspective is very different from

the personal one, the overlay may generate confu-

sion”;

• “It would be better to be able to choose whether

to apply the overlay mode or not”;

• “I like the overlay but I would also like to be able

to compare the two perspectives side by side”;

• (Our observation) some users worked only in the

shared perspective: they seemed to be too con-

fused with the personal perspective due to the

overlay;

• (Our observation) some users did not work be-

cause of many changes by others in the shared

perspective made them feel intimidated;

• (Our observation) for some users even small

changes brought about by others’ work seem to

easily generate confusion.

Seeing and Comparing

• “It could be useful to see others’ personal perspec-

tive and to import parts of them in my own”;

• “It could be useful to see everybody personal per-

spective to decide how to proceed with the joint

work; it would also help to understand the others’

point of view and learn from them”;

• “The app looks more useful to build personal per-

spectives rather than the shared one”.

Verbal Interaction

• “It would be useful to be able to explain to others

my own perspective and receive explanations on

theirs”;

• “Longer visible explanations would be useful”;

• “I would like to be able to add notes to nodes in

the shared perspective to better define concepts”;

• “Longer descriptions would allow to use Concept

Maps as effective summaries”;

• “Vocal or written chats might be useful to explain

concepts”;

• “Preliminary discussion could be useful to clarify

different approaches”;

• “It would be easier to understand (and accept)

changes if who is making them could explain what

s/he is doing”.

4 DISCUSSION

Participants undertook the experiment with an initial

positive bias on Concept Maps: according to ques-

tionnaire answers (see Figure 2) they believed Con-

cept Maps to be an effective support when learning a

subject, and that comparing map with fellow students

could contribute positively. As to the fruitfulness of

collaborative work on a Concept Map, people started

out with mixed feelings, probably due to a difference

in learning styles.

Knowing the participants’ opinion on the experi-

mental tasks per-se, independently from our tool or

interaction approach, together with the mostly posi-

tive evaluation on the Standard Usability Question-

naire, gives us a baseline to analyze their observed

behavior and their remarks, as well as their question-

naire answers.

If we look at the box-plot on the left in Figure 3,

we see that all the answers concerning the shared per-

spective ((b), (c) and (d)) reflect the same “divided-

ness” that participants originally had on the idea of

collaborating on a map. Comparing the two box-plots

in the figure (left and right) we however see that the

actual implementation of the shared perspective (on

the right) was perceived as less effective than its po-

tential (on the left) would suggest.

In order to better understand this feedback we

need to rely on our qualitative observation of the

learners’ process (Section 3.2.4). Almost all the par-

ticipants complained about how the overlay of the two

perspectives – and the constraint that the common el-

ements should have the same position in both – made

their personal perspective “unreadable”, as its spatial

arrangement was disrupted by the attempt at organiz-

ing the shared one. When they tried to rearrange their

personal perspective to restore their “meaning”, the

other group members complained that the shared one

had become unreadable in turn. For some people even

a minor change was enough to generate confusion.

This showed us that the spatial organization of the

concepts in a Concept Map is more significant than

we originally thought, sometimes and for some peo-

ple even more significant than the actual existence

of named relationships between the concepts. While

spatial organization, i.e. the map topology, is some-

times used to convey a specific meaning (e.g. hi-

erarchical structure, or order of importance), and at

least in part reflects the depth of learning, it seems

that – at least for our experiment subjects – it also ex-

pressed additional, sometimes implicit, sometimes in-

tuitively understood, relationships between the repre-

sented concepts. And, since the “shape” of a Concept

Map is captured with more immediacy at a glance

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

22

than the writings on it, it is the shape, i.e. the spa-

tial organization, that turns the graph made of nodes

and edges into a map, a tool one can actively use to

navigate the territory of her or his knowledge.

When the spatial organization was altered by an-

other participant, her/his team members found it dif-

ficult to recognize the knowledge under the changed

map, and lamented “disruption”, “meaninglessness”,

and “unreadability”. The difference among two learn-

ers’s perspective – and, for the sake of this argument,

we can regard the group as another learner, different

from all its members – seems to lie not so much in

the choice of concepts to represent, which were often

similar among people dealing with the same learning

materials, but in the relationship, both explicit (the

graph edges) and implicit (spatial organization).

Of course, a Concept Map can communicate

meaning even to readers without knowledge of its im-

plicit relationships. However, if we rearrange another

person’s map we are tampering with implicit relation-

ships which we are not aware of. In fact, our partic-

ipants did not complain about the shared perspective

being rearranged when they were away, even if they

did not always understand what had been done and

why. They rather complained about their own per-

sonal perspective getting rearranged in the process,

due to the overlay restriction that the shared position

always “won” over the personal one.

Disrupting a previous perspective in order to ac-

commodate for new knowledge and points of view

may well be a formative act, but in order to do so

the person has to participate in the break or change re-

flecting the evolution of her/his understanding. Due to

the mostly asynchronous nature of the collaboration

we proposed, this was not always possible: partici-

pants found the map rearranged, without being able to

participate in the process. The textual comments left

by the other team members did not appear to help their

understanding; some even remarked that they could

have related to the “disruption” of the map if it had

been rearranged “in real time”, with the person mak-

ing the changes explaining at the same time what s/he

was doing and why.

Many participants expressed the wish to be able to

see the others’ personal perspectives, in order to un-

derstand their work on the shared one. Some even said

that the most useful aspect of building a shared map

was, in their opinion, being able to see other people’s

perspective to learn from them.

This may suggest that working on a collaborative

concept map as a learning task, in order to better un-

derstand a topic by comparing and merging different

points of view, may include two collaboration goals,

that are, at least to a certain extent, independent from

each other:

1. collaboration in concept mapping (emphasis on

the process), where people support each other in

finding their own understanding, and

2. collaboration on a Concept Map (emphasis on the

result), where people contribute to a common ar-

tifact.

It has been argued by Hattie (2008) that a group-

oriented learning activity pursuing only the second

goal (i.e. a learning activity where a group is put to-

gether with the sole objective to produce an artifact,

without being guided to reflect on the collaborative

process) is scarcely effective. Then, process-oriented

collaboration, where people collaborate in order to

reach a personal goal (in this case knowledge acqui-

sition), emerges as a key factor in collaborative learn-

ing.

As some of our participants remarked, compar-

ing and importing other people’s maps (or parts of)

in one’s own work can be useful without even need-

ing to work on a shared version. And, even when a

group is assigned the task to produce a common map,

the process of building it can intertwine with the indi-

vidual processes, highlighting how personal learning

remains the ultimate goal.

Thus the lesson learned is that one of the main

challenges is allowing people to compare their Con-

cept Maps, recognizing commonalities and differ-

ences.

Our previous work (Goy et al., 2017) showed how

juxtaposing two maps with the same concepts in dif-

ferent positions makes for a very difficult compari-

son. The present experiment, however, showed that

the overlay feature did not seem to provide an optimal

solution, at least in its present incarnation, as shown

by the questionnaire answers in Figure 4.

An open discussion we had with our participants

at the end of the experiment suggested that combining

these two approaches (juxtaposition and overlay) may

allow to gain the advantages of both, at the same time

overcoming their limitations. In the combined ver-

sion, two overlays would be juxtaposed side by side,

each with a different perspective on top. Moreover,

the spatial organization would follow the perspective

on top.

These observations on the importance of compar-

ison tools suggests the need for the design of fea-

tures specifically supporting process-oriented collab-

oration. In particular, to name a few: the singling

out of recurring concepts, the recognition of common

clusters of concepts and relationships, the identifica-

tion of similar subtopics within different maps, and in

general the analysis of both graph structure and spa-

tial organization characterizing the different maps.

I Learn. You Learn. We Learn? An Experiment in Collaborative Concept Mapping

23

5 CONCLUSION

In this paper we have discussed a set of experiments

performed on a new prototype developed to investi-

gate a cooperative learning scenario based on Concept

Maps, where learners work on their individual per-

spectives, and are later engaged in team work to build

together a shared perspective. In particular, our re-

search focused on a collaboration type where people

can work remotely and asynchronously with respect

to each other. Learners were called to relate their own

personal perspective with the shared one, and com-

pare the two.

Our experiments highlighted some of the dynam-

ics that emerge during the development of a shared

perspective of knowledge. Of course, a learner will

always have a preferred and most effective way of

understanding and representing knowledge s/he is ac-

quiring, but it is important that s/he recognizes that

multiple representations are possible. Ideally, s/he

should also be ready to reconsider, review, and adapt

her/his understanding when others are involved, in

the light of their contributions. In practice, our ex-

periments showed that collaboration takes place in a

way that is often perceived as messy and difficult to

control, where people can be disoriented by actions

taken by others. In particular, integrating different

perspectives in a way that is understandable by ev-

eryone (even to those that do not agree with part of

the outcome) has proven to be a complex task. Ad-

mittedly, our approach to multi-perspective maps did

not take into account all the subtleties and and com-

plexities of this process.

As discussed above, process-oriented collabora-

tion emerged as a key element in collaboration when

learning. By process-oriented collaboration we mean

a collaboration whose goal is not necessarily the pro-

duction of a shared artifact, but rather helping each

other, by exchange and contamination, to build a bet-

ter personal perspective. This phase of exchange and

contamination can of course serve as a preliminary

work toward the creation of a shared perspective.

In most collaborative applications this type of col-

laboration is not taken into account, because the pur-

pose of the applications themselves is the produc-

tion of artifacts. Interestingly enough, an example

of a process-oriented collaborative environment can

be found in the field of computer programming. The

popular distributed version control system GIT (Cha-

con and Straub, 2014) supports various types of col-

laboration; among these, the possibility for different

people to extend and expand a set of programs or

libraries in various directions, comparing their code

and picking interesting elements from each other’s

work. While GIT also supports the merge of different

expansions in a single shared project, it does not en-

force it nor focuses exclusively on this aspect. Unfor-

tunately these advanced functionalities of GIT have

a quite steep learning curve, and are sometimes dif-

ficult to manage even for computer scientists. Our

current research direction focuses on designing how

to translate the GIT collaboration model (or at least

those parts of it that are pertinent to our goals) to the

context of collaborative learning by means of concept

maps.

REFERENCES

Attwell, G. (2007). Personal learning environments – the

future of elearning? Elearning papers, 2(1):1–8.

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., and Salovey, P. (2011). Emo-

tional intelligence: Implications for personal, social,

academic, and workplace success. Social and Person-

ality Psychology Compass, 5(1):88–103.

Ca

˜

nas, A., Novak, J. D., and Reiska, P. (2015). How good is

my concept map? am i a good cmapper? Knowledge

Management & E-Learning, 7(1):6–19.

Ca

˜

nas, A. J., Hill, G., Carff, R., Suri, N., Lott, J., and Es-

kridge, T. (2004). Cmaptools: A knowledge model-

ing and sharing environment. In Ca

˜

nas, A. J., No-

vak, J. D., and Gonz

`

alez, F. M., editors, Concept

maps: Theory, methodology, technology. Proceedings

of the first international conference on concept map-

ping, volume I, pages 125–133. Universidad P

´

ublica

de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain.

Chacon, S. and Straub, B. (2014). Pro Git. Apress.

Goy, A., Petrone, G., and Picardi, C. (2017). Personal and

shared perspectives on knowledge maps in learning

environments. In International Conference on Learn-

ing and Collaboration Technologies, pages 382–400.

Springer.

Grzega, J. and Sch

¨

oner, M. (2008). The didactic model ldl

(lernen durch lehren) as a way of preparing students

for communication in a knowledge society. Journal of

Education for Teaching, 34(3):167–175.

H

¨

akkinen, P. and H

¨

am

¨

al

¨

ainen, R. (2012). Shared and per-

sonal learning spaces: Challenges for pedagogical de-

sign. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(4):231–

236.

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800

meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Haugwitz, M., Nesbit, J. C., and Sandmann, A. (2010).

Cognitive ability and the instructional efficacy of col-

laborative concept mapping. Learning and Individual

Differences, 20(5):536 – 543.

Hertz-Lazarowitz, R., Kagan, S., Sharan, S., Slavin, R., and

Webb, C. (2013). Learning to cooperate, cooperating

to learn. Springer Science & Business Media.

Johnson, D. W. and Johnson, R. T. (2013). Coopera-

tive, competitive, and individualistic learning environ-

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

24

ments. In International guide to student achievement,

pages 372–374. Routledge.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., and Stanne, M. B. (2000).

Cooperative learning methods: A meta-analysis.

Kandiko, C., Hay, D., and Weller, S. (2013). Concept map-

ping in the humanities to facilitate reflection: Exter-

nalizing the relationship between public and personal

learning. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education,

12(1):70–87.

Khine, A. A., Adefuye, A. O., and Busari, J. (2019). Utility

of concept mapping as a tool to enhance metacogni-

tive teaching and learning of complex concepts in un-

dergraduate medical education. Arch Med Health Sci,

7(2):267–272.

Luff, P. and Heath, C. (1998). Mobility in collaboration.

In Proceedings of the 1998 ACM Conference on Com-

puter Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW ’98, pages

305–314, New York: ACM Press. ACM.

Meza, J., Jimenez, A., Mendoza, K., and Vaca-C

´

ardenas,

L. (2018). Collective intelligence education, enhanc-

ing the collaborative learning. In 2018 International

Conference on eDemocracy eGovernment (ICEDEG),

pages 24–30.

Novak, J. D. (2010). Learning, creating, and using knowl-

edge: Concept maps as facilitative tools in schools

and corporations. Routledge.

Nuninger, W. (2015). Optimiser les apprentissages avec les

cartes conceptuelles dans un cours hybrid

´

e : Evolution

de la posture et des comp

´

etences. In Colloque QPES.

Nuninger, W., Goy, A., Petrone, G., and Picardi, C. (2018).

Multi-perspective concept mapping in a digital inte-

grated learning environment: Promote active learning

through shared perspectives. In Bailey, L. W., editor,

Educational Technology and the New World of Per-

sistent Learning, chapter 7. IGI Global, University of

Phoenix, USA.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., and Chat-

terjee, S. (2007). A design science research method-

ology for information systems research. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 24(3):45–77.

Romero Garc

´

ıa, C., Cazorla, M., and Buz

´

on Garc

´

ıa, O.

(2017). Meaningful learning using concept maps as

a learning strategy. Journal of technology and science

education, 7(3):313–332.

Roscoe, R. D. and Chi, M. T. (2007). Understanding tutor

learning: Knowledge-building and knowledge-telling

in peer tutors’ explanations and questions. Review of

Educational Research, 77(4):534–574.

Sedelmaier, Y. and Landes, D. (2015). Active and induc-

tive learning in software engineering education. In

2015 IEEE/ACM 37th IEEE International Conference

on Software Engineering, pages 418–427.

Shea, J. H. (1995). Problems with collaborative learning.

Journal of Geological Education, 43(4):306–308.

Skaf-Molli, H., Ignat, C., Rahhal, C., and Molli, P.

(2007). New work modes for collaborative writing. In

Granville, B., Kutti, N. S., Missikoff, M., and Nguyen,

N. T., editors, International Conference on Enterprise

Information Systems and Web Technologies, EISWT-

07, pages 176–182. ISRST.

Smit, D. W. (1989). Some difficulties with collabora-

tive learning. Journal of Advanced Composition,

9(1/2):45–58.

Webb, N. M. (2013). Information processing approaches to

collaborative learning. In Hmelo-Silver, C. E., Chinn,

C. A., Chan, C. K., and O’Donnell, A., editors, The in-

ternational handbook of collaborative learning, pages

19–44. ROUTLEDGE.

Webb, N. M. and Mastergeorge, A. M. (2003). The devel-

opment of students’ helping behavior and learning in

peer-directed small groups. Cognition and instruction,

21(4):361–428.

Wilson, S., Liber, O., Johnson, M., Beauvoir, P., Sharples,

P., and Milligan, C. (2007). Personal learning envi-

ronments: Challenging the dominant design of educa-

tional systems. Journal of E-learning and Knowledge

Society, 3(2):27–38.

I Learn. You Learn. We Learn? An Experiment in Collaborative Concept Mapping

25