Enabling Stakeholders to Change: Development of a Change

Management

Guideline for Flipped Classroom Implementations

Linda Blömer, Alena Droit and Uwe Hoppe

*

Institute of Information Management and Information Systems Engineering, Osnabrueck University,

Katharinenstr. 3, Osnabrueck, Germany

Keywords: Blended Learning, Flipped Classroom, Change Management, Stakeholder, Guideline.

Abstract: The successful introduction of the popular blended learning method Flipped Classroom (FC) is a major

challenge because many stakeholders are affected. However, the transformation is dependent on the

commitment of engaged individuals, who rarely have access to institutionalized support. Repeatable

descriptions of strategic approaches and recommendations for how to manage a successful change in Higher

Education Institutions are rare. This paper aims to synthesize research findings concerning Change

Management (CM) approaches in a flipped learning context. Based on a systematic literature review, we

develop a Guideline with specific recommendations for successful CM to develop and implement FC courses.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of 2000 Blended Learning (BL)

has emerged as one of the most popular e-learning

concepts (Güzer & Caner, 2014). BL can be best

described as “a blending of campus and online

educational experiences for the express purpose of

enhancing the quality of the learning experience”

(Garrison & Vaughan, 2013). There are several BL

methods that Higher Education Institutions (HEI) can

use in their curricula, the most popular of which is

currently the Flipped Classroom (FC) (Said & Zainal,

2017). In an FC, mere knowledge transfer takes place

outside the classroom, e.g. by using videos, podcasts,

and reading assignments (Said & Zainal, 2017). The

in-class time of an FC can be arranged differently

according to the needs; the main focus is on the

application of the knowledge imparted online,

problem-oriented and collaborative learning as well

as discussions between students and teachers

(McLean, Attardi, Faden, & Goldszmidt, 2016).

Transforming traditional lectures into FCs can be

very complex and time-consuming, not only due to

the fact that new contents and materials have to be

produced and provided, but more importantly because

throughout the whole process of development and

implementation, different stakeholder groups have to

be considered. Though some guidelines and models

*

https://www.wiwi.uni-osnabrueck.de

for the systematic development of FCs exist, they

primarily concentrate on content creation (Lee, Lim,

& Kim, 2017), technical solutions (Herzfeldt,

Kristekova, Schermann, & Krcmar, 2011), and

student experience (Chiang & Chen, 2017). New

teaching methods need a careful introduction

(Triantafyllou & Timcenko, 2015), and specific

project requirements such as Change Management

(CM) have to be taken into account (Herzfeldt et al.,

2011). Research shows that more than fifty percent of

organizational changes fail, mainly due to the

resistance of affected stakeholders, rather than

difficulties concerning technology or organizational

structures (Bondarev, 2018). Stakeholders can

develop a resistance to change either because they

lack the knowledge and extent of the change, are

uncertain about the results, fear the unknown, are

afraid of innovation or because they think that they

lack certain competencies (Bondarev, 2018). Flavell

has discovered in an extensive literature research, that

especially academic staff has issues to embrace new

technologies (Flavell, Harris, Price, Logan, &

Peterson, 2018), which are essential to creating FC

courses. More specifically the low perceived value

and relevance of technology (Debuse, Lawley, &

Shibl, 2008), the fear of potential failure (Howard,

2013), lacking confidence (Dusick & Yildirim, 2000)

and a lack of resources and support for new

technologies (Adams Becker, Cummins, Davis, Hall

Blömer, L., Droit, A. and Hoppe, U.

Enabling Stakeholders to Change: Development of a Change Management Guideline for Flipped Classroom Implementations.

DOI: 10.5220/0009352402270237

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 1, pages 227-237

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

227

Giesinger, & Ananthanarayanan, 2017) are reported

issues. Students, administration and other HEI staff

show signs of resistance to change during the FC

development as well (Bishop & Verleger, 2013).

Implementing an effective CM at universities is,

therefore, necessary, but very challenging since HEIs

are organizations that mainly consist of experts who

are working quite independently in research and

teaching (Morisse, 2016).

Although several studies have identified the

relevance of CM in HEIs (Bondarev, 2018), the

establishment of CM strategies and its integration into

e-learning concepts, especially the FC, is rare (Flavell

et al., 2018). Due to the defined lack of applicable

models and approaches that include stakeholders and

their motivation, this paper aims to present a Flipped

Classroom Change Management Guideline (FC

CM

Guideline). Doing so, we will answer the following

three research questions: (1) What current research

can be found regarding the change from traditional

lectures to FC courses? (2) Which specific change

management tasks regarding the transition from

traditional classes to FC courses exist in this

literature? (3) How can the specific tasks be assigned

to stakeholder groups and summarized as

recommendations for action within the framework of

a Guideline? To answer these questions, we conduct

an intensive literature research. We describe our

literature search in chapter 2 and give an overview of

the findings in chapter 3. We then identify specific

tasks and recommendations for action and summarize

them in our FC

CM

Guideline in chapter 4.

2 METHOD

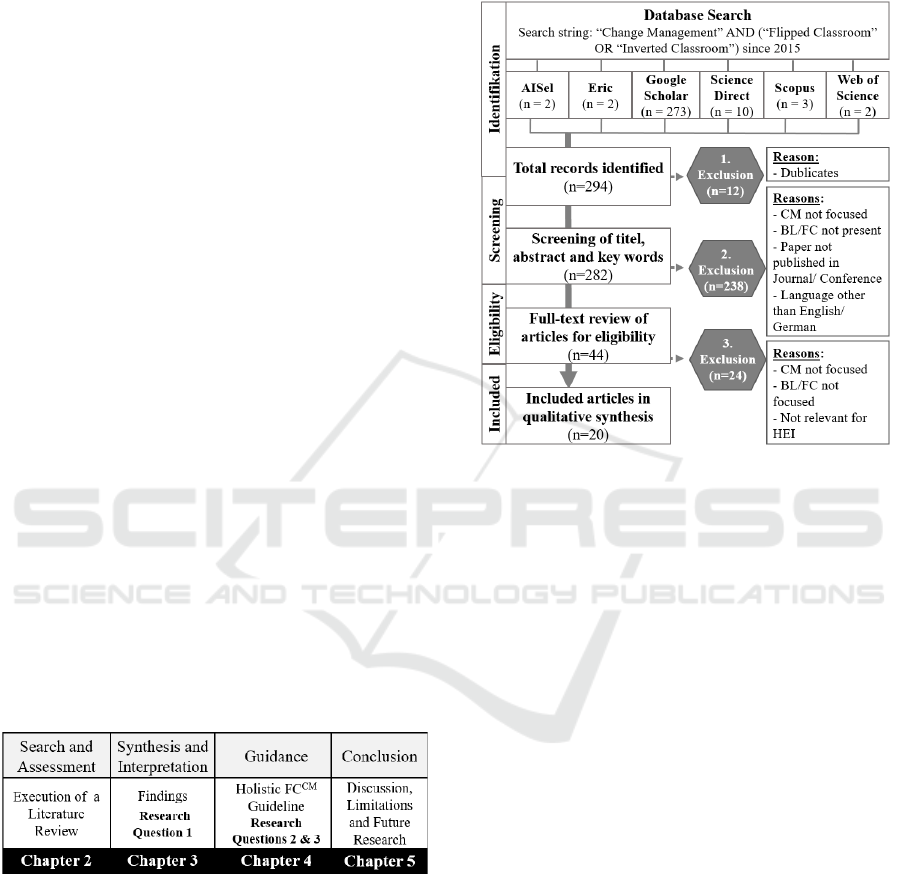

Figure 1: Research Process.

To build the FC

CM

Guideline on a solid foundation,

we conduct a systematic literature review (Webster &

Watson, 2002) considering the research phases search

and assessment, synthesis and interpretation,

guidance as well as a conclusion (Schryen, 2015).

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the research

process by relating the respective phases of the

literature review to the main focus of each chapter and

the corresponding research questions.

The aim of our search is to obtain an overview of

current research concerning CM in an FC context

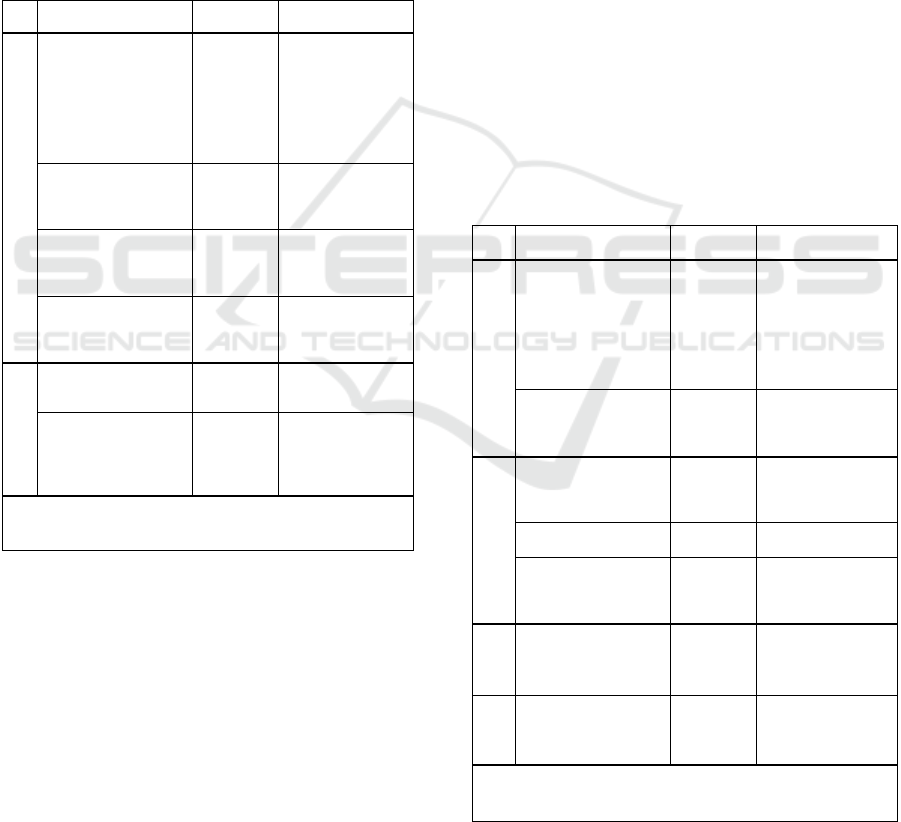

with a focus on existing CM tasks. Figure 2 shows the

procedure of the systematic literature review in detail.

Figure 2: Systematic Literature Review.

We used a fixed search string shown in figure 2 in

recommended databases for IS research (Schryen,

2015): AISel, Google Scholar, Science Direct,

Scopus, and Web of Science. We also used ERIC

(Education Resources Information Center) as a sixth

database to include a more educational point of view.

We only include articles published since 2015 to

focus on current research. We then review the results

in two steps and select them according to specific

criteria (Figure 2). After the first exclusion of

duplicates, we use predefined criteria to review the

title and abstracts of the remaining papers (n=282).

The underlying criteria relate to relevance, quality,

and feasibility. In order to evaluate the relevance of

the source in terms of content, a reference to CM and

FC, or at least to BL, should be recognizable in the

abstract. For example, articles often deal with the

implementation of an FC in which CM is a topic of

the affected course - however, the change process to

FC that is of interest here is not addressed. In order to

ensure the quality of the data, only published articles

and conference papers are considered. For the sake of

feasibility, sources that are not written in English or

German are also excluded. The remaining articles and

papers (n=44) are checked for their eligibility in a

subsequent full-text review. As before, the underlying

criteria is used to check the articles and papers. In

addition, articles that are not considered relevant for

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

228

the HEI context (e.g. articles referring to K1-12) are

excluded at this point since the present study deals

with the change to FC in HEI.

3 FINDINGS IN SYSTEMATIC

LITERATURE REVIEW

Our systematic literature research resulted in 20

articles. Surprisingly, in most articles we found, there

was no usage or mention of any strategic CM

approaches for transforming traditional classes to FC,

even though that is often recommended (Bondarev,

2018). However, most articles mention the

importance of CM and describe different CM actions,

that were executed at their own HEI or observed in

case studies.

Concerning the year of publication, it is striking

that most papers were published within the last two

years (n=15), showing the topicality of the papers.

The 20 articles, which serve as a further basis,

originate from 12 different countries, including

Germany, Sweden, Australia, Chile, Pakistan and the

US. It is surprising that only one article has its origins

in the US because generally most studies on FC

originate from there (Harris, Harris, Reed, & Zelihic,

2016) – however, the usage and research of CM

approaches do not seem to have been increasingly

addressed so far. The sources also vary in study

design, e.g. project reports, case studies, literature

analysis, as well as qualitative and quantitative

surveys. There is a clear tendency towards case

studies (n=7) and project reports (n=6), showing that

the dominating part of research available is case-

based. This can lead to a “siloed” character of the

research field, lacking systematic approaches. Since

our guideline is based on these very different sources,

we hope develop a guideline for practitioners and

researchers that is applicable to different countries

and for different approaches.

4 DEVELOPMENT OF THE

GUIDELINE

After identifying the relevant articles (n=20), we

collected and interpreted the CM tasks that can be

found in the papers. In this step, two researchers, who

are both experienced in implementing FCs,

independently read the articles in regard to specific

CM tasks and then synthesized their results. A total

number of 132 tasks was identified and bundled on

the basis of similar content into 58 specific tasks. We

summarized the tasks into 34 more general

recommendations for action, which in turn are

classified into ten upper categories, more precisely

described in the following chapter.

4.1 Overview of the Guideline

The ten derived categories are motivation, leadership,

creation of a team, communication, culture and

climate, goals and vision, removal of barriers,

collaboration, infrastructure and technology, and

feedback and adjustments. There is no universally

valid order of the categories, but figure 3 shows one

possible way to organize them.

Figure 3: FC

CM

Guideline Overview.

Regardless of which stakeholder is driving the FC

idea forward, the core process of the FC

CM

Guideline

starts with the HEI management, that should support

the idea and adapt its leadership accordingly, as well

as with the creation of an FC development team. They

then create goals and a vision for the transformation.

Barriers of stakeholder groups have to be removed,

and collaboration, inside and outside of the HEI

should be encouraged. The FC development team

should periodically collect feedback and adapt the

development and implementation correspondingly.

There are several categories that cannot be put into a

specific order since they support multiple tasks of the

core process. At all times, but especially in the

beginning, it is important to motivate stakeholders

and create incentives for them to participate. The

culture and climate within the HEI should support

innovative thinking and create an atmosphere of trust.

The infrastructure and technology have to be planned

by the project team and provided to students and

teachers to enable a successful implementation.

Throughout the whole CM process, communication

within and between the stakeholder groups is the key

for a successful change to FC. The corresponding

recommendations for action and specific tasks are

explained in chapter 4.2.

Enabling Stakeholders to Change: Development of a Change Management Guideline for Flipped Classroom Implementations

229

4.2 Recommendations and Specific

Tasks

In the following chapter, we present the

recommendations and specific tasks for each of the

ten categories, in the order of the categories shown in

figure 3. For each category, we first present a table

(see table 1-10) and then provide additional

information, like concrete examples from case

studies. Each table shows the name of the

recommendation, multiple related specific tasks, the

stakeholder groups, who are mainly responsible for

the tasks, and a reference to the articles.

Table 1: Leadership.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder References

1. Leadership style

Give the project team

and teachers enough

autonomy, have faith in

teachers, use a mixture

of top-down and bottom-

up policies

H, PM

(Adekola, Dale, &

Gardiner, 2017;

Charbonneau-Gowdy

& Chavez, 2018;

Liebscher et al.,

2015; Van

Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

Embrace success and

mistakes, collect

feedback, learn from it

and communicate it

H, F, PM

(Adekola et al.,

2017; Charbonneau-

Gowdy & Chavez,

2018)

Acknowledge teachers’

fears and do not tell

them their ways are

outdated

H, PM, PT

(Collyer &

Campbell, 2015; Van

Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

Communicate clearly

that excellent education

is one of the HEIs major

goals, not only research

H, F (White et al., 2016)

2. Conditions

Provide infrastructure,

training, funding,

support

H, PM

(Adekola et al.,

2017; Collyer &

Campbell, 2015)

Ensure that there are

explicit guidelines and

policies for e-learning to

reassure teachers and

give orientation

H, F, PM

(Adekola et al.,

2017)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Leadership: The HEI management and project team

should ensure proper working conditions for the FC

transformation, like the supply of infrastructure,

training, funds, and guidelines (Adekola et al., 2017).

Explicit guidelines and policies for e-learning provide

teachers with ethics and legal orientation (Adekola et

al., 2017; Iqbal, Ahmad, & Willis, 2017). One of the

drivers for change can be nationwide governmental

policies for the implementation of technology-

enhanced learning (Iqbal et al., 2017). The

effectiveness of leadership is highly dependent on the

leadership style. Research recommends that leaders

have to carefully communicate with stakeholders, for

example, not telling teachers that the way they have

taught for the last 20 years was wrong, and they have

to do everything differently now. Instead appreciate

what they have done before, explain to them that the

usage of new technologies can help to make their

courses even better and show the benefits (Collyer &

Campbell, 2015; Van Twembeke & Goeman, 2018).

Some authors state, that neither only a bottom-up nor

a top-down approach work for most HEIs, but instead

the combination of both (Charbonneau-Gowdy &

Chavez, 2018; Liebscher et al., 2015; Van Twembeke

& Goeman, 2018). Great support of the senior

management for the FC project as well as single

motivated teachers (Van Twembeke & Goeman,

2018) are major factor for the success of the project

(Adekola et al., 2017). The HEI management should

have faith in teachers and grant them a certain

autonomy (Adekola et al., 2017) because otherwise

teachers might feel forced, disempowered and settle

for less (Charbonneau-Gowdy & Chavez, 2018).

Duisburg-Essen University’s management

deliberately chose the way via faculty committees to

involve all status groups at an early stage in the sense

of promoting ownership (Liebscher et al., 2015).

Table 2: Creation of a team.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

3. Members

Involve teachers,

students, faculty,

development leaders,

curriculum designers,

technology support,

management

H, PM

(Hurtubise, Hall,

Sheridan, & Han,

2015; Hutchings &

Quinney, 2015;

Nordquist, Sundberg,

& Laing, 2016; Van

Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

Choose resilient and

experienced team

members for success

H, PM

(Charbonneau-Gowdy

& Chavez, 2018;

Owen & Dunham,

2015)

4. Roles and tasks

Declare change agents

who set routine meetings

& manage team climate,

collecting feedback

PM

(Hurtubise et al.,

2015; Nordquist et al.,

2016; Van Twembeke

& Goeman, 2018)

Establish leadership;

form a guiding coalition

H, PM

(Hurtubise et al.,

2015)

Develop curricular

goals, define new ways

of assessments, select

technology tools

PM, PT, T,

C

(Hurtubise et al.,

2015)

5. Working

approach

Use for example an

iterative agile approach

to implement FCs

PM, PT

(Owen & Dunham,

2015)

6. Team

spirit

Establish trust and open

communication within

the team

PM, PT

(Hutchings &

Quinney, 2015;

Nordquist et al., 2016)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Creation of a Team: The FC project team should be

a multidisciplinary task force (Nordquist et al., 2016)

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

230

with experienced members and clearly defined

leadership by a project manager (Charbonneau-

Gowdy & Chavez, 2018), who also acts as a role

model (Daniel, Hüther, & Ohngemach, 2018). Team

members draw on the enthusiasm, experience, and

commitment of each other to deal with challenges and

constraints (Hutchings & Quinney, 2015) and it is

therefore very important to meet periodically (Van

Twembeke & Goeman, 2018) and to establish trust

within the team (Owen & Dunham, 2015). If the

project team chooses an iterative agile approach for

the implementation of FCs, it has to remember that

besides the advantages explained in detail by Schoop

et al., existing institutional systems and structures at

university might not be compatible with agile

approaches (Owen & Dunham, 2015).

Table 3: Goals and vision.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

7. E-learning strategy

Address different fields in

your strategy: didactics,

technology, organization,

economy, culture

H, PM, PT

(Schoop, E., Köhler,

T., Börner, C., Schulz,

J. , 2016)

Define e-learning goals,

set interims targets

H, PM, PT

(Liebscher et al.,

2015; White et al.,

2016)

Define quality criteria and

measures, integrated into

the university’s quality

management system and

test these throughout the

project

PM, PT

(Daniel et al., 2018;

Hurtubise et al., 2015;

Schoop et al., 2016)

8. Vision

Build a task force of

stakeholders, including

faculty, students,

administration, facility

management, educate all

members of the task force,

and create a shared vision

H, PM, PT

(Nordquist et al.,

2016; White et al.,

2016)

Communicate the vision

by sharing the intent and

value of FC with students

and other stakeholders

H, PM, PT,

T

(Hurtubise et al.,

2015)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Goals and Vision: HEIs should not engage in e-

learning just to use new technologies; e-learning is a

tool and not a solution (Liebscher et al., 2015). That

is why it is so important to define an e-learning

strategy that includes specific goals (White et al.,

2016) and interim targets (Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018), with defined quality criteria and

measures (Schoop et al., 2016). Some universities

might have to develop new methods of teaching

evaluations (Daniel et al., 2018) to measure those

criteria. It is important to evaluate throughout the

different project stages and beyond to compare

results, e.g., in order to see if student satisfaction or

learning outcomes have improved (Hurtubise et al.,

2015). A task force should be founded to develop a

vision for the institution and communicate it

(Nordquist et al., 2016; White et al., 2016).

Table 4: Removal of barriers.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

9. Time and effort

Start small, instead of

reconstructing the whole

syllabus right away begin

with partly transforming

units into FC

PT, T (Harris et al., 2016)

Release involved teachers

from parts of their duties

during the

implementation of an FC

H, F

(Berglund et al.,

2017; Owen &

Dunham, 2015)

10. Financial

resources

Minimize impact on staff

time by supplying e-

tutors or additional

teaching assistants

H, F

(Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018;

White et al., 2016)

Provide money for new

infrastructure and

technology, ensure

sustainable funding

H, F

(Liebscher et al.,

2015; Schoop at al.,

2016)

11. Teacher training

Offer in-depth training

for media competence,

technology usage, LMS,

copyright issues. Provide

easily understandable

materials in the local

language

PM, PT, IT

(Berglund et al.,

2017; Hurtubise et

al., 2015; Liebscher

et al., 2015; Van

Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

Hire e-learning teachers

who organize regular

sessions and consulting

hours

PM, PT (Schoop et al., 2016)

12. Teacher support

Implement peer to peer

teacher classroom

observations for

discussions and reflection

T, PT

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Berglund et al., 2017)

Provide long term support

through mentors,

consultants, D-guides,

center for university

didactics

H, PM, IT

(Berglund et al.,

2017; Charbonneau-

Gowdy & Chavez,

2018; Collyer &

Campbell, 2015;

Daniel et al., 2018;

Dion et al., 2018.;

Schoop et al., 2016)

Provide emotional

support and exemption of

other tasks

H, PM

(Schoop et al., 2016;

Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

13. Student inclusion

Include students in

decision-making

processes from the

beginning, create student-

staff collaborations, hire

students for the

development and

planning of FCs

PT, T

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Daniel et al., 2018;

Harris et al., 2016;

Hurtubise et al.,

2015)

14. Student

support

Offer classes for media

skills, techniques to study

efficiently and time

management

PT, T, IT (Schoop et al., 2016)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Removal of Barriers: Removing barriers is the most

important task to lower the resistance of involved

Enabling Stakeholders to Change: Development of a Change Management Guideline for Flipped Classroom Implementations

231

stakeholders. In terms of finances, the HEI

management and the project team need to develop a

plan for sustainable financing of the infrastructure,

technologies, and personnel needed for the FC

(Liebscher et al., 2015), that goes further than just

start-up funding (Schoop et al., 2016). One barrier is

the fear or lack of digital literacy of teachers. The

literature search resulted in many articles that pointed

out the importance of specific training for teachers.

There are for example 30 credit graduate classes for

teaching e-learning classes (Dion et al., o. J.), and the

possibility of hiring e-learning coaches, who offer

introductions to FC teaching, workshops and regular

courses (Collyer & Campbell, 2015). E-learning

coaches should offer regular consultation hours, so

that inexperienced as well as advanced teachers can

always ask the questions that are relevant for their

individual level of FC implementation and the

problems that might occur during a semester (Collyer

& Campbell, 2015; Daniel et al., 2018), e.g. about

new ways of online assessments or decreasing

attendance rates. The aim of the training is to give

lecturers both confidence and support in order to

effectively prepare excellent teaching (Schoop et al.,

2016). Van Twembeke and Goeman pointed out the

need for customized materials for teachers, that are

easy to understand, and provided in the teacher’s

language (Van Twembeke & Goeman, 2018).

Teachers should receive ongoing support from

mentors or a university center for HEI didactics

(Charbonneau-Gowdy & Chavez, 2018; Daniel et al.,

Table 5: Collaboration.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

15. Community

Build communities of

practice for teachers

with different

backgrounds or

communities of

knowledge for experts

PT

(Berglund et al., 2017;

Schoop et al., 2016;

Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018; White

et al., 2016)

Organize networking

events for all

stakeholders to share

experience

PT

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Schoop et al., 2016)

Establish cross-

university networks and

name local coordinators

who share experiences in

regular meetings

H, PT

(Berglund et al., 2017;

Dion et al., o. J.;

Schoop et al., 2016)

16. Peer

mentoring

Organize peer mentoring

by early adapters,

facilitate classroom

observations

PT

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Berglund et al., 2017;

Charbonneau-Gowdy

& Chavez, 2018;

Liebscher et al., 2015)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

2018). At the DHBW Karlsruhe for example,

information systems students are trained as D-Guides

(digital guides) over the course of eight weeks. They

then help teachers to transform their lectures to FCs.

Usually three D-guides get appointed to one teacher

for ten weeks, which equals 300 hours of the

additional workforce for the teacher to redesign a

course (Daniel et al., 2018).

Collaboration: Many authors named collaboration,

both inside and outside of the university, as an

impactful factor for a successful FC implementation.

Within the HEI, the project team should establish

communities of practice for teachers to learn together

(Schoop et al., 2016), where more experienced FC

teachers present their accomplishments and learning

materials (Charbonneau-Gowdy & Chavez, 2018;

Liebscher et al., 2015; White et al., 2016). Teachers

can talk about pedagogical issues (Adekola et al.,

2017) and have a discussion in a collegial setting

(Berglund et al., 2017). These communities can be

powerful motivators for extending e-learning

(Adekola et al., 2017; Schoop et al., 2016). To

enhance teaching competence, the KTH Royal

Institute of Technology (Sweden) organized

classroom observations, were teachers visited each

other’s BL lectures in small groups, followed by

discussions and reviews of the observations

(Berglund et al., 2017). They also appointed part-time

pedagogical developers (PDs) in faculties who

facilitate networking and knowledge exchange

among faculty members (Van Twembeke & Goeman,

2018). Hutchings and Quinney describe the

networking with other HEIs and with experts of

different disciplines facilitated through the HEA

Enhancement Academy (UK) as a powerful resource

of information and support (Hutchings & Quinney,

2015). Not only experiences can be shared in cross-

university networks, but they can also be used to

share learning materials and carry out joint online

assessments (Schoop et al., 2016). Dion et al. report

on EIT Digital, a Knowledge and Innovation

Community funded by the European Union that offers

a European network for universities who want to

adapt BL (Dion et al., 2018). Each involved

university designates an experienced local

coordinator, who leads the CM at his university and

also attends multiple physical coordinator meetings to

share results and feedback (Dion et al., 2018).

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

232

Table 6: Feedback and adjustments.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

17. Feedback

Survey students and

teachers, examine

learning outcomes,

collect data on quality

measures

PT, T

(Collyer & Campbell,

2015; Hurtubise et al.,

2015)

18.

Improvement

Use survey and

feedbacks in class and

training sessions to

constantly monitor and

improve the outcomes

PT, T

(Collyer & Campbell,

2015; Hurtubise et al.,

2015)

19. Results

Share feedback locally

first, then share in

education and

technology publications

and with the e-learning

community

PT, T

(Hurtubise et al.,

2015)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Feedback and Adjustments: During and after the

implementation of an FC, it is important to regularly

collect feedback of students and teachers, e.g., using

qualitative surveys (Collyer & Campbell, 2015).

Feedback like students’ perceptions of the process,

discussed locally, amongst teachers, in project

meetings or with HEI management (Hurtubise et al.,

2015) and it has to be decided which changes should

be made accordingly to the feedback. The assessed

data should be compared to previous years; gathered

longitudinal data on curricula outcomes could also be

shared with the (inter-)national community

(Hurtubise et al., 2015).

Table 7: Motivation of stakeholders.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

20. Incentives

Create rewarding

systems that reward

engaged staff with

scholarship and

promotions

H, F (Adekola et al., 2017)

Provide prizes for

involved staff, e.g. for

"Educational

development of the year"

H (Berglund et al., 2017)

Offer extra funding for

teachers and faculties

H (Schoop et al., 2016)

Work on real-world

projects with real

customers during in-

class time as incentive

for students

C, T

(Pisoni, Marchese, &

Renouard, 2019)

21. Information

Show teachers benefits

of using technology, like

better pedagogical

practice, more flexibility

for students, better

learning outcomes;

communicate benefits in

presentations

PM

(Collyer & Campbell,

2015)

22. Voluntariness

Work with teachers who

volunteer first, start

pilots and test materials

PM, PT

(Charbonneau-Gowdy

& Chavez, 2018;

Collyer & Campbell,

2015; Daniel et al.,

2018; Hurtubise et al.,

2015; Owen &

Dunham, 2015)

23. Acknow-

ledgement

Show teachers that their

hard work is valued and

communicate it openly

H, F

(Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

24. Needs

Survey students and find

out about their fears and

wishes (e.g., 75% prefer

BYOD)

PT (Bondarev, 2018)

Survey well-being and

current workload of staff

as well as their digital

literacy and their wishes

for training

PT, F

(Daniel et al., 2018;

Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Motivation of Stakeholders: Since implementing an

FC takes a lot of time and effort, HEIs can motivate

teachers by using tangible incentives (Berglund et al.,

2017), like providing additional funds for rewards

and prizes (Berglund et al., 2017; Schoop et al.,

2016). It is also important to recognize the efforts

publicly, as colleagues and learners are often unaware

of the workload an FC implementation requires (Van

Twembeke & Goeman, 2018). Working with

interested teachers who volunteer as early adopters is

easier in the beginning since those teachers are

already more open to new teaching formats,

innovative teaching and the new understanding of

Table 8: Culture and climate.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

25. Encouragement

Peer-mentoring for

emotional support to help

with fear of failure,

workshops by early

adopters

PT, S, T

(Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018; White

et al., 2016)

Communicate willingness

to fail and learning from

mistakes

H, F, PM

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Charbonneau-Gowdy

& Chavez, 2018)

Establish a CM Process

that gives stakeholders time

to free themselves from old

patterns

H, PM

(Daniel et al., 2018;

Liebscher et al., 2015)

26. Team

spirit

Work together on

institutional success, open

communication, and trust

H, PT, T (Berglund et al., 2017)

27. Appre-

ciation

Provide public recognition

of success, reward

accomplishments but also

appreciate basic efforts

H, PM

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Berglund et al., 2017;

Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Enabling Stakeholders to Change: Development of a Change Management Guideline for Flipped Classroom Implementations

233

roles (Daniel et al., 2018). Experimental approaches

should be encouraged, and early adopters can then

promote FCs and peer mentor other teachers

(Adekola et al., 2017; Daniel et al., 2018).

Culture and Climate: The predominant culture in the

institution has a large impact on the successful change

to FC, but it is a long and complex process to change

the culture itself. If the HEIs culture penalizes failure,

it can lead to more risk-averse teachers and staff, who

then, out of fear, are not willing to try out innovations

anymore. Therefore, management should

communicate that they will back teachers up if any of

their FC implementations fail (Adekola et al., 2017;

Charbonneau-Gowdy & Chavez, 2018). The results

of 18 interviews with FC teachers showed that they

had to deal with negativity of colleagues inside and

outside of their own department who were skeptical

towards e-learning and it created an atmosphere of

distrust, which can potentially lead the change

management process to fail (Owen & Dunham,

2015). Encouragement from colleagues and a

cooperative climate seem to be major factors for the

engagement of single teachers and overall successful

e-learning projects (Owen & Dunham, 2015; Van

Twembeke & Goeman, 2018; White et al., 2016). The

fear of failure, especially from older or digitally less

literate teachers should be taken seriously (Van

Twembeke & Goeman, 2018) as they need emotional

support (Daniel et al., 2018) and a slow and gentle

change management process in order not to feel

overwhelmed or frustrated (Liebscher et al., 2015).

Table 9: Infrastructure and technology.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

28. Infrastructure

Cooperate with facility

management and build

flexible learning spaces

for students, redesign

laboratory space for

group works and

discussions, provide

teachers with shared

workspaces

H, PM, PT

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Nordquist et al., 2016;

Pisoni et al., 2019;

Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

29. Technology

Avoid untested

technologies and tools,

keep it small and simple

and start with basic

functionalities, focus on

reliability, stability high

performance and user

experience

IT, PM, PT

(Charbonneau-Gowdy

& Chavez, 2018;

Collyer & Campbell,

2015; Daniel et al.,

2018; Dion et al.,

o. J.)

30. Usage

Provide support for

students and teachers,

maintain the systems and

keep them up-to-date

IT

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Collyer & Campbell,

2015; Dion et al.,

o. J.)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Infrastructure and Technology: It is often

overlooked that the HEI should redesign learning

spaces to support FC teaching. Students need flexible,

interactive workspaces with good internet access to

prepare the online-materials (Adekola et al., 2017;

Pisoni et al., 2019) and for the interactive, group work

in-class activities, rooms with flexible furniture,

soundproof room dividers and touch screen monitors

with shared screens support FC teaching (Nordquist

et al., 2016). If teachers decide to use online exams,

spacious laboratory rooms are needed as well

(Hutchings & Quinney, 2015). Concerning the

technology, the FC project team should introduce

well-established up-to-date solutions, preferably

from vendors with a long history and ongoing support

(Collyer & Campbell, 2015). All technology,

including the Learning Management Systems (LMS)

has to be reliable, stable and efficient; otherwise

teachers and students can get frustrated and reject the

technology (Charbonneau-Gowdy & Chavez, 2018;

Daniel et al., 2018). Technical support for students

and teachers has to be guaranteed at all times (Collyer

& Campbell, 2015).

Table 10: Communication.

No. Specific CM tasks Stakeholder Ref.

31. Discussions

Conduct periodic peer

discussions and regular

stakeholder meetings in

which preconceptions

about FC can be

rectified

PM, PT

(Charbonneau-Gowdy

& Chavez, 2018; White

et al., 2016)

32.

Linkaging

Support internal

systems for

communication and

create communities of

practice

H, PM

(Van Twembeke &

Goeman, 2018)

33. Enlightning

Communicate with the

students in the early

beginning of FC

projects, explain the

benefits, expectations

and their

responsibilities

T

(Adekola et al., 2017;

Dann, 2019; Harris et

al., 2016; Morisse,

2016)

34. Visualization

Promote achievements

in a staff meeting, via

e-mails and newsletters

PM, H

(Collyer & Campbell,

2015; Van Twembeke

& Goeman, 2018;

White et al., 2016)

Organize e-teaching

events for the

community

PT (Schoop et al., 2016)

(H) HEI management, (F) faculty chairs, (T) teachers, (C) curriculum

designers, (PM) FC project manager, (PT) FC project team, (IT) IT

staff, (S) students

Communication: Communication is important

during all CM tasks. Communication can be internal,

within the HEI, e.g., amongst teachers, amongst

teachers and students or HEI management and other

stakeholders. The tone of communication is crucial;

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

234

constructive discussions should be promoted (White

et al., 2016), and an atmosphere where every

stakeholder is allowed to openly talk about the

impacts of FCs without feeling judged should be

ensured (Charbonneau-Gowdy & Chavez, 2018).

When the project team or the HEI management talk

to instructors, it is important to do so according to the

teacher’s reality and objectives; instead of using

technical terms, product or vendor’s names (Collyer

& Campbell, 2015). Teachers need to clearly

communicate with students, especially during the

early stages of implementing an FC. Students have to

adjust to the new teaching model and to new ways to

learn (Harris, Harris, Reed, & Zelihic, 2016), e.g.

more independently and self-paced when working on

online lectures. They need explanations about the

benefits of an FC as well as the teachers telling them

explicitly what is expected from them in an FC

(Adekola et al., 2017; Dann, 2019), e.g. being

prepared before in-class activities. External

communication and promotion of the FC project are

also crucial. HEIs could use newsletters to inform

about the latest FC developments, show

demonstrations, make FC pilots available outside of

the institution or organize an e-teaching day as the TU

Dresden did in 2015 (Collyer & Campbell, 2015).

5 CONCLUSION

To fully exploit the possibilities of an FC, the

consideration of a CM strategy is essential (Hurtubise

et al., 2015). Our literature research has shown that

many authors have recognized the important role of

CM in the DT of education. However, how to convert

this awareness into practice? To empower

stakeholders to manage the change to FC by

involving them to reduce resistance and to increase

motivation, we identified specific CM tasks from

literature for different stakeholder groups and built a

FC

CM

guideline. The guideline consists of ten upper

categories, which include a total of 34

recommendations of action and 58 specific tasks, as

well as further explanations and examples.

The most common topics in the selected articles

were communication and collaboration, especially

amongst teachers. Institutions should encourage

stakeholders to discuss and exchange ideas and

support new structures for networking, within their

own institution and in cross-university networks. In

most cases, the tasks described in our guideline can

be assigned to several stakeholder groups, who have

to work together. Successful fulfillment is therefore

generally dependent not only on one group of people

but on functioning cooperation between different

groups. Our findings show how important it is to

recognize that a sustainable and successful FC

transformation must be supported by all stakeholders,

not just by single motivated teachers, as often

described in case studies. This is also supported by

observations of some researchers, that neither just a

bottom-up or only a top-down approach effectively

work for the FC implementation, but a combination

of both (Charbonneau-Gowdy & Chavez, 2018;

Liebscher et al., 2015; Van Twembeke & Goeman,

2018).

We rate the FC

CM

guideline as useful for

researchers and practitioners who are interested in a

holistic view of the change process accompanying the

implementation of FCs at HEIs. We consider all

stakeholders in our guideline, compared to others that

solely focus on the inclusion of teachers and students.

Our guideline creates an awareness of which tasks

one has to perform oneself and which tasks have to be

performed by other persons in order for the change to

FC to succeed. Therefore, we think that the guideline

leads to a more transparent distribution of tasks as

well as to a better mutual understanding of the

affected groups. We provide an overview of

recommendations for action as well as concrete tasks

and current examples from the literature. Our

guideline is easy to understand and can be extended

by the user. As our model does not claim to be

complete, with this paper, we like to encourage other

researchers to look for recommendations for action

and publish their findings to enlarge the research

field. We aim to build a basis for discussion for

researchers and practitioners to enhance effective FC

implementations. For further development, we aim to

evaluate the guideline. With the help of qualitative

interviews, we will iteratively improve our results and

include different views from all types of stakeholders.

Relevant stakeholders for the interviews will be

lecturers, students, student tutors, IT staff, and –to

bridge the gap between administration and student

needs– program coordinators and HEI management.

The proceeding of the evaluation will orient towards

the principles of model evaluation (Frank, Fettke, &

Loos, 2007; Österle & Otto, 2010). We also consider

developing an agile version of the FC

CM

model.

Although we based our guideline on well-prepared

literature research, it is possible that other models

exist, that would be suitable as well. Depending on

the size, equipment and financial resources of an HEI,

fewer or different stakeholder groups than those

mentioned here could be affected by the change,

which would lead to a different distribution of tasks.

Before the guideline can be applied, it is advisable to

Enabling Stakeholders to Change: Development of a Change Management Guideline for Flipped Classroom Implementations

235

identify all affected stakeholder groups. Research that

presents the application of the guideline within case-

studies could deliver further valuable improvement.

REFERENCES

Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Davis, A., Hall

Giesinger, C., & Ananthanarayanan, V. (2017). NMC

Horizon Report: 2017. Higher Education Edition.

https://www.nmc.org/publication/nmc-horizon-report-

2017-higher-education-edition/

Adekola, J., Dale, V. H. M., & Gardiner, K. (2017).

Development of an institutional framework to guide

transitions into enhanced blended learning in higher

education. Research in Learning Technology, 25(0), 1–

16. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v25.1973

Berglund, A., Havtun, H., Jerbrant, A., Wingård, L.,

Andersson, M., Hedin, B., & Kjellgren, B. (2017). The

pedagogical developers initiative—Systematic shifts,

serendipities, and setbacks. 13th International CDIO

Conference, 497-508.

Bishop, J. L., & Verleger, M. A. (2013). The flipped

classroom: A survey of the research. ASEE National

Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, GA, 30, 1–18.

Bondarev, M. (2018). University Students’ Readiness For

E-Learning: Replacing Or Supplementing Face-To-

Face Classroom Learning. 18th PCSF 2018 -

Professional Сulture of the Specialist of the Future,

1151–1160.

https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.124

Charbonneau-Gowdy, P., & Chavez, J. (2018). Endpoint:

Insights for theory development in a blended learning

program in chile. 17th European Conference on e-

Learning, ECEL 2018, 81–89.

Chiang, F., & Chen, C. (2017). Modified Flipped

Classroom Instructional Model in „Learning Sciences“

Course for Graduate Students. The Asia - Pacific

Education Researcher, 26(1–2), 1–10.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-016-0321-2

Collyer, S., & Campbell, C. (2015). Enabling Pervasive

Change: A Higher Education Case Study. EdMedia+

Innovate Learning, Association for the Advancement of

Computing in Education (AACE), 249-255.

Daniel, M., Hüther, J., & Ohngemach, C. (2018). Smile–

Studierende als Multiplikatoren für innovative und

digitale Lehre. DeLFI 2018-Die 16. E-Learning

Fachtagung Informatik, 57-68.

Dann, C. E. (2019). Blended Learning 3.0: Getting Students

on Board. In V. L. Uskov, R. J. Howlett, L. C. Jain, &

L. Vlacic (eds.), Smart Education and e-Learning 2018,

214–223.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92363-5_20

Debuse, J. C. W., Lawley, M., & Shibl, R. (2008).

Educators’ perceptions of automated feedback systems.

Australasian Journal of Educational Technology,

24(4), 374-386. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1198

Dion, G., Dalle, J.-M., Renouard, F., Guseva, Y., León, G.,

Mutanen, O.-P. Stranger, A.P., Pisoni, G., Stoycheva,

M., Tejero, A., Vendel, M (2018). Change

Management: Blended Learning Adoption in a Large

Network of European Universities. 1-8.

Dusick, D. M., & Yildirim, S. (2000). Faculty Computer

Use and Training: Identifying Distinct Needs for

Different Populations. Community College Review,

27(4), 33–47.

https://doi.org/10.1177/009155210002700403

Flavell, H., Harris, C., Price, C., Logan, E., & Peterson, S.

(2018). Empowering academics to be adaptive with

eLearning technologies: An exploratory case study.

Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35,

1–15. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2990

Frank, U., Fettke, P., & Loos, P. (2007). Evaluation of

Reference Models. In Reference Modeling for Business

Systems Analysis (S. 118–140). IGI Global.

Garrison, D. R., & Vaughan, N. D. (2013). Institutional

change and leadership associated with blended learning

innovation: Two case studies. The Internet and Higher

Education, 18, 24–28.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.09.001

Güzer, B., & Caner, H. (2014). The Past, Present and Future

of Blended Learning: An in Depth Analysis of

Literature. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences,

116, 4596–4603.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.992

Harris, B. F., Harris, J., Reed, L., & Zelihic, M. M. (2016).

Flipped classroom: Another tool for your pedagogy tool

box. Developments in Business Simulation and

Experiential Learning: Proceedings of the Annual

ABSEL conference, 43, 325–333.

Herzfeldt, A., Kristekova, Z., Schermann, M., & Krcmar,

H. (2011). A Conceptual Framework of Requirements

For The Development of E-Learning Offerings From a

Product Service System Perspective. AMCIS, 1–10.

Howard, S. K. (2013). Risk-aversion: Understanding

teachers’ resistance to technology integration.

Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 22(3), 357–372.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2013.802995

Hurtubise, L., Hall, E., Sheridan, L., & Han, H. (2015). The

Flipped Classroom in Medical Education: Engaging

Students to Build Competency. Journal of Medical

Education and Curricular Development, 2, 35–43.

https://doi.org/10.4137/JMECD.S23895

Hutchings, M., & Quinney, A. (2015). The flipped

classroom, disruptive pedagogies, enabling

technologies and wicked problems: Responding to ‘the

bomb in the basement’. Electronic Journal of E-

Learning, 13, 106–119.

Iqbal, S., Ahmad, S., & Willis, I. (2017). Influencing

Factors for Adopting Technology Enhanced Learning

in the Medical Schools of Punjab, Pakistan.

International Journal of Information and

Communication Technology Education (IJICTE),

13(3), 27–39.

Lee, J., Lim, C., & Kim, H. (2017). Development of an

Instructional Design Model for Flipped Learning in

Higher Education. Educational Technology Research

and Development, 65(2), 427–453.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9502-1

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

236

Liebscher, J., Petschenka, A., Gollan, H., Heinrich, S., van

Ackeren, I., & Ganseuer, C. (2015). E-Learning-

Strategie an der Universität Duisburg-Essen—Mehr als

ein Artefakt? Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung,

10(2), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.3217/zfhe-10-02/07

McLean, S., Attardi, S. M., Faden, L., & Goldszmidt, M.

(2016). Flipped classrooms and student learning: Not

just surface gains. Advances in Physiology Education,

40(1), 47–55.

https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00098.2015

Morisse, K. (2016). Inverted Classroom in der

Hochschullehre–Chancen, Hemmnisse und

Erfolgsfaktoren. Das Inverted Classroom Modell.

Begleitband zur 5. Konferenz Inverted Classroom and

Beyond, 1–11.

Nordquist, J., Sundberg, K., & Laing, A. (2016). Aligning

physical learning spaces with the curriculum: AMEE

Guide No. 107. Medical Teacher, 38(8), 755–768.

https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1147541

Österle, H., & Otto, B. (2010). Consortium Research.

Business & Information Systems Engineering, 2(5),

283–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-010-0119-3

Owen, H., & Dunham, N. (2015). Reflections on the Use of

Iterative, Agile and Collaborative Approaches for

Blended Flipped Learning Development. Education

Sciences, 5(2), 85–103.

https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5020085

Pisoni, G., Marchese, M., & Renouard, F. (2019). Benefits

and Challenges of Distributed Student Activities in

Online Education Settings: Cross-University

Collaborations on a Pan-European Level. 2019 IEEE

Global Engineering Education Conference

(EDUCON), 1017–1021.

https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2019.8725194

Said, M. N. H. M., & Zainal, R. (2017). A Review of

Impacts and Challenges of Flipped-Mastery Classroom.

Advanced Science Letters, 23(8), 7763–7766.

https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2017.9571

Schoop, E., Köhler, T., Börner, C., Schulz, J. (2016).

Consolidating eLearning in a Higher Education

Institution: An Organisational Issue integrating

Didactics, Technology, and People by the Means of an

eLearning Strategy. Proceedings of 19th Conference

GeNeMe, 39-50.

Schryen, G. (2015). Writing Qualitative IS Literature

Reviews—Guidelines for Synthesis, Interpretation, and

Guidance of Research. Communications of the

Association for Information Systems, 37, 286–325.

https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.03712

Triantafyllou, E., & Timcenko, O. (2015). Student

behaviors and perceptions in a flipped classroom: A

case in undergraduate mathematics. Proceedings of the

Annual Conference of the European Society for

Engineering Education 2015 (SEFI 2015).

Van Twembeke, E., & Goeman, K. (2018). Motivation gets

you going and habit gets you there. Educational

Research, 60

(1), 62–79.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2017.1379031

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the Past to

Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review.

MIS Quarterly, 26(2), xiii–xxiii.

White, P. J., Larson, I., Styles, K., Yuriev, E., Evans, D. R.,

Rangachari, P. K., … Naidu, S. (2016). Adopting an

active learning approach to teaching in a research-

intensive higher education context transformed staff

teaching attitudes and behaviours. Higher Education

Research & Development, 35(3), 619–633.

Enabling Stakeholders to Change: Development of a Change Management Guideline for Flipped Classroom Implementations

237