Text Processing Procedures for Analysing a Corpus with Medieval

Marian Miracle Tales in Old Swedish

Bengt Dahlqvist

Department of Linguistics and Philology, Uppsala University, P.O. Box 635, 751 26 Uppsala, Sweden

Keywords: Text Mining, Medieval Texts, Miracle Stories, Old Swedish, Stop Words, Word Similarity,

Spelling Variations, Key Words.

Abstract: A text corpus of one hundred and one Marian Miracle stories in Old Swedish written between c. 1272 and

1430 has been digitally compiled from three transcribed sources from the 19

th

Century. Highly specialized

knowledge is needed to interpret these texts, since the medieval variant of Swedish differs significantly from

the modern form of the language. Both the vocabulary and spelling as well as the grammar show substantial

variances compared to modern Swedish. To advance the understanding of these texts, automated tools for

textual processing are needed. This paper preliminary investigates a number of strategies, such as frequency

list analysis and methods for identifying spelling variations for producing stop word lists and exposing the

key words of the texts. This can be a help to understand the texts, identifying different word forms of the same

word, to ease a lexicon lookup and be a starting point for lemmatisation.

1 INTRODUCTION

To make computer analyses of texts in Old Swedish,

which was in use between 1225 and 1534, is still not

an easy task. The standard lexicon for Old Swedish

was prepared in the late 19

th

Century by the Swedish

philologist (Söderwall, 1884). An electronic version

of this exist, but gives no support for spelling variants

nor word inflections, which makes it hard to use

practically for unknown word forms. Very little

support exists for automated tasks. For instance, an

efficient part-of-speech tagger or a parser is not to be

found, even if some work in this area has been done

in the last years (Adesam, 2016). Neither has not

much been done regarding the essential problems for

this type of text, which shows many features that are

problematic to handle, foremost in the area of the rich

morphology and abundance of word forms. A non-

specialist user, wishing to understand or even

translate a given text, faces many problems. In this

paper, a number of text processing strategies will be

discussed and applied to a small corpus of medieval

miracle tales.

Especially, focus here will be given to the inherent

problems of word analysis, the elimination of word

variants and text normalisation to be able to identify

word content with rich lexical meaning. This can be

seen as a first step in an ongoing research aiming at

developing more automated text processing tools for

analysing texts written in Old Swedish, primarily

with the aim to mine and deconstruct texts into

constituents and group similar forms together.

Aside from this, the texts themselves are

interesting as witnesses of religious thinking at the

time and as evidence of the interchange and

translation of textual material within the European

medieval culture. More and better tools for the

analysis of Old Swedish as such may in this way pave

the way for more serious studies of the content of

these types of texts, and help to facilate both literary

understanding and analysis.

2 THE DATA MATERIAL

The data material used in this study consists of 101

medieval miracle tales in Old Swedish where the

Virgin Mary figures as a saint and wonder worker.

This text collection is believed to consist of all

surviving complete tales of this kind.

Miracle tales constitute a specific subgenre in

medieval religious writing, aside from hagiographies,

visions and moral tales. The contents of miracle tales

on the whole are for the most part purely apocryphal,

in that they do not originate from the Bible. They also

often take place in later times, after the death of the

452

Dahlqvist, B.

Text Processing Procedures for Analysing a Corpus with Medieval Marian Miracle Tales in Old Swedish.

DOI: 10.5220/0009372204520458

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2020) - Volume 1, pages 452-458

ISBN: 978-989-758-395-7; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

protagonist saint. Stories of this type were common

in many European languages at the time, from Latin

and Greek to French and German. Translations were

produced into several other languages, including Old

Norwegian, Danish and Swedish.

In the following, we will describe the three

sources for our text material in Old Swedish more in

detail.

2.1 The Old Swedish Legendary

The Old Swedish Legendary (“Fornsvenskt

Legendarium”) is a collection of apocryphal tales

describing the lives and miracles of Christian saints

in a chronological fashion, starting from the Virgin

Mary and the apostles and continuing through

medieval times, up to the time when the stories were

composed, around 1276-1307. There exists some

consent that these stories are for the greatest part

translations from the work in Latin by Voragine, the

Legenda Aurea (c. 1260). It is not known exactly

where in Sweden the translation and writing was

conducted. Surviving today, are foremost two

manuscripts, copies of a lost original, Codex

Bureanus (c. 1350) and Codex Bildstenianus (c.

1420). The former comprises today only a third of the

original.

A transcription of the handwritten medieval

Legendary was published by the Swedish philologist

George Stephens in three parts between 1847 and

1874. The corpora constructed for and under

investigation in this paper is in part based on this

work. A total of twenty-five stories with miracle tales

of the Virgin Mary was gathered from part I (20 tales,

Stephens, 1847) and part III (5 tales, Stephens, 1874)

and digitally entered into the corpus. The total text

mass of these 25 tales was found to be 8 106 words.

2.2 Book of Miracles

The so called Book of Miracles, written in Old

Swedish under the title “Järteckensbok”, is part of the

medieval manuscript Codex Oxenstierna from 1385,

authored at the Vadstena monastery which was

founded the same year. This collection contains

among other things sixty-six miracle tales with the

Virgin Mary.

A transcription was published by the Swedish

philologist G. E. Klemming in the later part of the 19

th

Century (Klemming, 1877). The 66 stories with Mary

have been digitized and included in our corpus along

with material from the previously mentioned

legendary. This text, with 66 Marian miracles,

contains 11 262 words.

2.3 Solance for the Soul

The manuscript “Själens Tröst”, which can be

translated as “Solance for the Soul”, contains among

other texts ten miracle tales with the Virgin Mary.

These texts have been included in our corpus, and

consist of 1 934 words. This manuscript was also

authored at the Vadstena monastery, c. 1430. A

transcription was published by the Swedish

philologist G. E. Klemming in the late 19

th

Century

(Klemming, 1871).

2.4 The Corpora

The corpora created from the three sources described

above consist of 101 separate stories with a total of

21 302 proper words. The number of unique words is

4 971, and this thus constitutes the vocabulary of the

text as a whole.

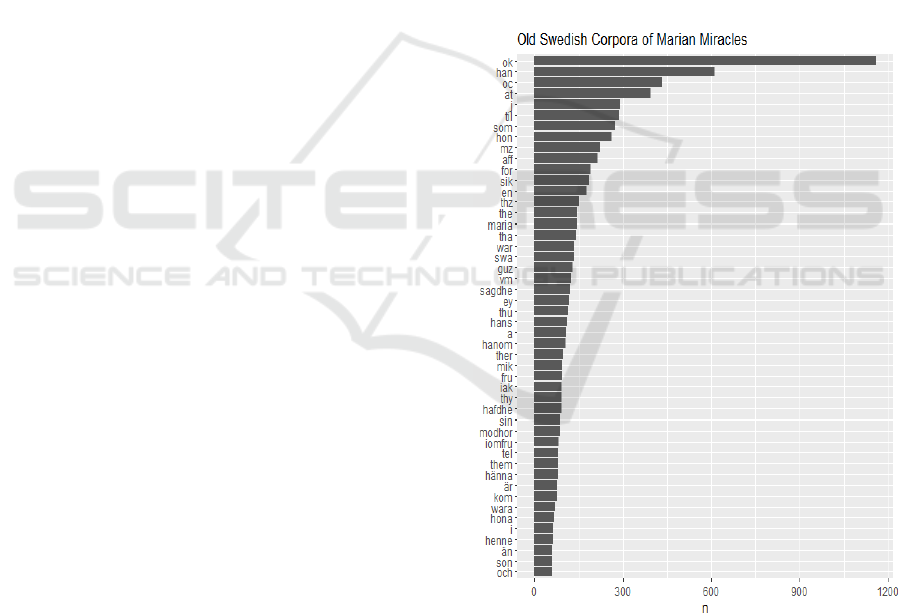

Figure 1: The words in the corpora presented with their

frequency in falling order.

In figure 1 above is presented a frequency list in a

graphical form for the words of the corpora. The most

frequent word is seen here to be “ok”, which means

“and”, and it is occurring 1 160 times in our corpora.

Already in this list we see the problem with spelling

variants, since the third most frequent word is “oc”,

Text Processing Procedures for Analysing a Corpus with Medieval Marian Miracle Tales in Old Swedish

453

which is one of the variants for “ok”. That particular

form is occurring 434 times.

3 TEXT PROCESSING

The text material in our corpus needs processing in

order to make it more accessible and suitable for

further analysis. Especially problematic in contrast

with modern Swedish are the plentiful spelling

variants for the same word and the use of numerous

inflections. Further, the sometimes different word

order compared to the modern usage, the occasional

absence of a proper subject and the frequent absence

of punctuation for marking sentence endings is also

problematic, but outside the scope of this paper.

3.1 Text Normalisation

To facilitate comparisons between ingoing words of

the corpora, the text should undergo some

normalisation. This means that as a first measure a

number of special characters found in the text are

replaced by more ordinary characters to make further

treatment more efficient. In practice, the replacement

should not make it impossible to access the original

form occurring in the text, since this of course can be

of significant value to the researcher.

The two ligatures present in the text, ‘æ’ and “fl”,

are resolved into their constituent parts ‘ae’ and “fl”.

Further, some characters substitutions are made. The

ancient rune sign “þ”, often present in Old Swedish

texts before c. 1350, is replaced by the phonetically

corresponding “th”. Actually, “þ” can also represent

the sound or string “dh”. This is the case for

“høghtiþ”, (Eng. Holiday), in the early Legendary, in

the later Book of Miracles written as “höghtidh”.

Also, the for the modern mind more familiar letters

“å”, “ä” and “ö” (including the variant “ø”), are

replaced by the standard representations “aa”, “ae”

and “oe”. The steps of the procedure are listed in table

2 below.

Table 1: List of character replacements done for the texts.

Character string Replacement string

þ

th

flfl

æ ae

øoe

å aa

ä ae

öoe

Together with this procedure of character

replacements, the text as a whole is converted to

smaller lowercase letters.

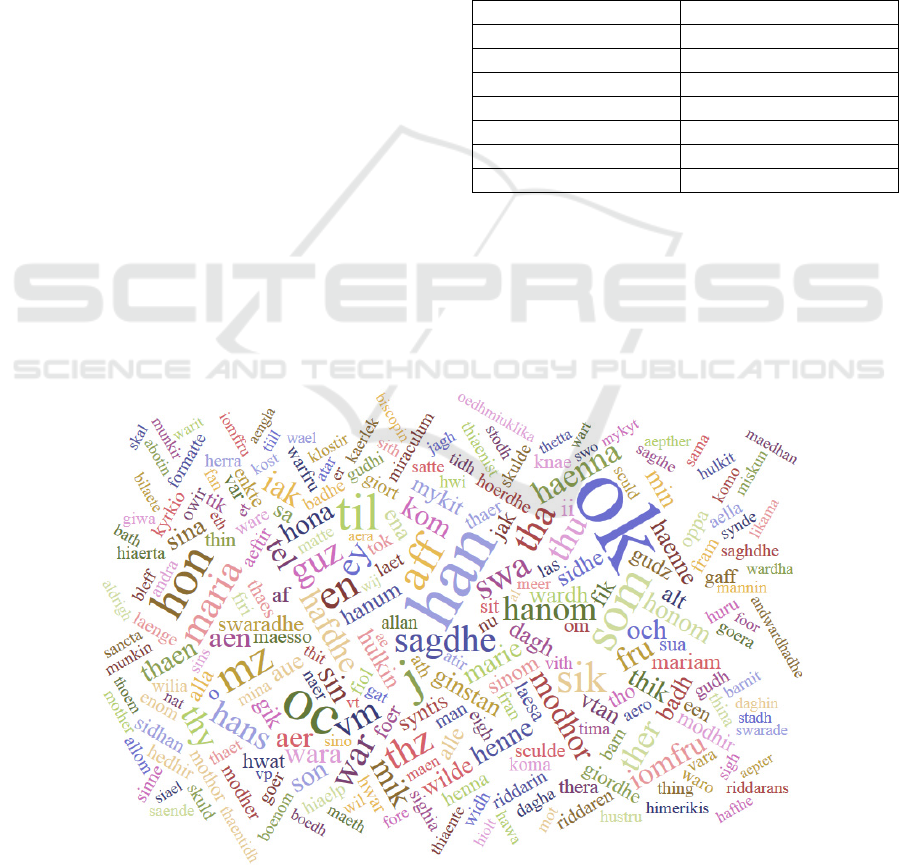

The effect of this normalisation on a word level can

be seen in figure 2 above, where the 150 most

frequent words of the text are shown with their size

proportional to their frequency in the material.

Figure 2: A word cloud for the corpus after text normalisation.

NLPinAI 2020 - Special Session on Natural Language Processing in Artificial Intelligence

454

As can be seen in the figure, some prominent

words are “oc”, “ok”, “han” and “hon”. The two first

are spelling variants for the word “och” (“and” in

English), while the two later are the pronouns for

“him” and “she”, respectively. In this respect, Old

Swedish conforms, not surprisingly, to most other

languages in that the function words, with little

lexical meaning, are dominating in any given text.

A remedy for this would be to subtract such words

by the means of a stop word list. Unfortunately, no

such list is available for Old Swedish, so we will later

have to construct one, to be able to continuing with

the work.

3.2 Spelling Variants

Old Swedish shows a tendency to spell rather loosely

and have many variants for the same word. For

example, the common word for “and” is found in

several variants, such as “och”, “oc” and “ok”. This

behaviour is also true for verbs, for instance “to

serve” can be written as either one of the word forms

“þiäna”, “þiena”, “þiana”, “thiana”, “þyäna”, “tyäna”

or “thena” (today, in modern Swedish, the word is

written as “tjäna”). Of course, the spelling went

through several changes during the centuries when

Old Swedish was in use, but the fact is that a single

text from this period often exhibits several variants of

the same word. In table 2 below is given eight variants

of the word for “virgin” (or “maiden”), in modern

Swedish written as “jungfru”. The table also shows

the frequency of these variants as they occur in our

text corpus.

Table 2: Spelling variants of the word for “maiden”.

Word form Frequency

iomfru 82

iomffru 11

j

omfru 10

iomffrv 9

iomfrw 5

j

omffrv 4

j

umfru 2

iomffrw 2

As seen from the table, some letters seem to be easily

exchangeable, “v”, “w” and “u” in one group and “o”

and “u” for another. Also, noteworthy is that a double

“ff” can be used instead of a single “f”. For example

this is true for the word for “of” (English), which can

be written both as “af” or “aff”. Also note that “i” and

“j” seem interchangeable.

This means that text normalisation could be

further extended, in addition to the previously

described spelling substitutions, to also include

variant word form exchanges. A suitable strategy

could be to replace the multitude forms with the most

frequent for each particular word. Here, one also has

to consider the morphology of Old Swedish, much

richer as compared to modern Swedish (or English,

for that matter). In Old Swedish we find four cases for

the nouns, adjectives and pronouns (nominative,

accusative, dative and genitive), three genders for the

adjectives and pronouns (masculine, feminine and

neuter) as well as three modus (indicative,

conjunctive and imperative) for the verbs (Delsing,

2017). All taken together, this gives rise to numerous

and diverse inflections and word forms.

3.3 Word Similarity

A possible method for detecting e.g. variant word

spellings inherent in the text could be to utilise some

measure of word similarity. The thought would then

be that word forms that are representing the same

word would cluster together. There are a number of

measurements in existence that gives a distance or

similarity between pair of words. Several of these, for

example the Levenshtein algorithm, are based upon a

numbering of necessary insertions, addition and

deletions for going from one word to the other.

It is however unclear if using that kind of

measurement is a sound strategy in regard to the

spelling variant problem for Old Swedish. Such

methods give an integer or fraction as a distance

measure, which may be unsuitable due to the low

variation. In the following, we limit our interest to

two particular methods of a bit different merit, the

Soundex and the Winkler-Jaro methods.

3.3.1 The Soundex Measure

A soundex representation of a written word is

connected to its phonetical value. Most

implementation are however made for American

speech, and for Old Swedish certainly none exists.

The knowledge of how words actually were

pronounced during medieval times is also limited,

even if for instance the changes in vocal

pronunciation is fairly detailed mapped out for the

period. The usefulness of such information may of

course be quite limited when applied to written text

and variants of words. For example, one can take the

word for “mother”, originally spelled “moþir” and in

our corpus after normalisation having five variants as

shown in table 3.

Text Processing Procedures for Analysing a Corpus with Medieval Marian Miracle Tales in Old Swedish

455

Table 3: The variant words for “mother”.

Variant word Soundex value

modho

r

m360

modhi

r

m360

modhe

r

m360

motho

r

m360

mothe

r

m360

The data in table 3 shows that Soundex for this

example, and also for many others, works quite well.

However, the start of the string is important, and the

Soundex algorithm, which is developed with English

in mind, fails for instance to find any significant

equality for words beginning with “i” or “j”. A single

symbol plus a three-digit representation might also be

too narrow to catch more subtle similarities or

differences. Soundex might be more useful that some

string metrics, but unless a version is developed that

take pronunciation for Old Swedish in account it may

be unsatisfactory as a working tool.

3.3.2 The Winkler-Jaro Distance

Another string measurement is the Winkler-Jaro

distance metric. Despite its name, it is not a true

metric, and more of a similarity than a distance

(Winkler, 1990). It is computed for words pairwise,

with the resulting value 1 for perfectly equal strings

and 0 for unequal ones (i.e. strings having completely

different characters). The ingoing parameters for the

measure are the string length, the number of matching

characters and the number of transpositions.

Table 4: Pairwise similarity values for “jomfru” (“virgin”).

Word forms Winkler-Jaro

j

omfru -

j

omffrv 0.9095

j

umfru -

j

omfru 0.9000

j

omfru - iomfru 0.8889

j

omfru - iomffru 0.8492

j

umfru - iomfru 0.7778

j

omfru - iomfrw 0.7778

j

umfru -

j

omffrv 0.7714

j

umfru - iomffru 0.7460

j

omfru - iomffrw 0.7460

j

omfru - iomffrv 0.7460

j

umfru - iomfrw 0.6667

j

umfru - iomffrw 0.6429

j

umfru - iomffrv 0.6429

The computation of this measure can yield any

floating number between zero and one, so its

comparison power should perhaps be better that both

Levenshtein and Soundex. In table 4 below we see as

an example the pairwise Winkler-Jaro values for the

word “jomfru” (Eng. “virgin” or “maiden”) in its

different spelling variants in the corpora.

As can be seen from the table, the Winkler-Jaro

measure gives high scores for these related word

pairs, and these also occur quite adjacent in the full

listing. Seemingly, this measure might be a good

choice for finding and grouping related word forms

together.

The relation may then be either a matter of

spelling variation or a closeness due to inflectional

causes. In both cases, this information is helpful in

inventorying the text and giving clues for lexicon

look-ups, either manual or automated.

3.4 Stop Word List

Stop word lists are used for subtracting non-specific

or uninteresting words from any given text. Such a list

typically consists of some of the most frequent words

in any language, belonging to closed word classes,

such as determiners, pronouns, prepositions and

conjunctions. Also, auxiliary verbs might be included

in such lists.

For use here, a stop word list was constructed by

examining the frequency list of the corpora. The

principles used for choosing words were in

accordance with the general ideas behind stop word

lists and resulted in a list of 74 specific words:

"honom", "hans", "a", "ok", "oc", "han", "hon",

"at", "mz", "the", "them", "ther", "swa", "af", "aff",

"ey", "foer", "i", "j", "ii", "jak", "jac", "thz", "til",

"vm", "vtan", "som", "sit", "sin", "sina", "sinom",

"aar", "aeftir", "aen", "aer", "alle", "alt", "aat", "een",

"enkte", "for", "haenna", "haenne", "hanom",

"hanum", "henna", "henne", "hona", "hulkin",

"hwar", "hwat", "iak", "mik", "sidhan", "sidhe", "sik",

"tel", "tha", "thaen", "thaer", "thaes", "then", "thera",

"thik", "thin", "tho", "thu", "thy", "tik", "war",

"wara", "wardth", "wilde" and "hafdhe”.

Further, variants of the name Maria were brought

together into the most frequent form.

The result of this procedure made upon the

already normalised text, as described previously, of

the corpora can be seen in figure 3 below. Here, words

with lexical meaning now appear, that seem to be

characteristic of the texts in the corpora. This is

probably the best we can accomplish in terms of a text

analysis for finding key words in the absence of a

reference corpora for what would constitute a

“normal” text in Old Swedish.

NLPinAI 2020 - Special Session on Natural Language Processing in Artificial Intelligence

456

Figure 3: A Word Cloud for the Corpus after Applying Both Text Normalisation and a Stop Word List.

4 CONCLUSION

Natural language processing for Old Swedish is still

an area rather undeveloped, a feature it has common

with many other medieval languages no longer in use.

For research purposes, this is unfortunate, since large

materials of written texts remain unexplored and are

accessible only to a small number of specialists, who

are working more or less traditionally, without the aid

of much digital tools.

This paper has identified some of the problems

with analysing texts in Old Swedish, due to the

particularities of the language. In turn, the topics of

text normalisation and word variant spotting has been

discussed, with examples from a corpus of religious

miracle texts.

Further, the use of similarity measures has been

discussed, and two such have been given special

attention. It seems that the Winkler-Jaro metric could

be a suitable candidate for usage when studying word

forms in Old Swedish.

Finally, as a result of a frequency analysis, a stop

word list for Old Swedish has been constructed. This

has also, together with a text normalisation, been

applied to the corpus at hand, and been found to yield

a result which looks promising for extracting key

words or words with substantial lexical meaning.

5 FUTURE WORK

Future work in this area would for example be to

applying the text procedures to facilitate the

understanding and translation (for the benefit of

literary analysis) of the full 101 tales in the corpus. A

preliminary translation of a subset of 65 stories, done

without much computational support (Dahlqvist,

2019), has already been realised and in a way

prompted this work. The text procedures outlined

could possibly also be extended for a more formal

lemmatisation and sentence analysis of Old Swedish.

Also, the study of non-common, or negative key

words, or even hapax legomena, after applying stop

words, could be a help to identify geographical or

proper names in the texts. Of special interest could

also be to study non-Old Swedish text insertions, e.g.

of Latin, since such are occurring in the tales with a

substantial frequency.

REFERENCES

Adesam, Y and G. Bouma, 2016. “Old Swedish part-of-

speech tagging between variation and external

knowledge”. In Proceedings of the 10th SIGHUM

Workshop on language Technology for Cultural

Heritage, Social Sciences, and Humanities, pp. 32-42,

Association for Computational Linguistics. Berlin.

Text Processing Procedures for Analysing a Corpus with Medieval Marian Miracle Tales in Old Swedish

457

Dahlqvist, Bengt, 2019. “Tales in Old Swedish of Marian

Miracles”. In Proceedings of the 2

nd

Colloquium on the

Miracles of Our Lady, from the Middle Ages to Today,

in press. ICR, Rennes.

Delsing, Lars-Olof, 2017. “The morphology of Old Nordic

II: Old Swedish and Old Danish”, in The Nordic

Languages. An International Handbook of the History

of the North Germanic Languages, pp. 925-939, De

Gruyter Mouton. Berlin.

Klemming, G. E., 1871. Själens tröst. Tio Guds bud

förklarade genom legender, berättelser och exempel, P.

A. Norstedt & Söner, Kongl. Boktryckare. Stockholm.

Klemming, G. E., 1877. Klosterläsning. Samlingar utgivna

av Svenska fornskriftsällskapet, P. A. Norstedt & Söner,

Kongl. Boktryckare. Stockholm.

Stephens, George Esq., 1847. Ett forn-svenskt legendarium,

innehållande medeltids kloster-sagor om helgon,

påfvar och kejsare ifrån det 1:sta till det XIII:de

århundradet. Efter Gamla Handskrifter, del 1,, P. A.

Norstedt & Söner, Kongl. Boktryckare. Stockholm.

Stephens, George Esq., 1874. Ett forn-svenskt legendarium,

innehållande medeltids kloster-sagor om helgon,

påfvar och kejsare ifrån det 1:sta till det XIII:de

århundradet. Efter Gamla Handskrifter, del 3, P. A.

Norstedt & Söner, Kongl. Boktryckare. Stockholm.

Söderwall, K. F., 1884. Ordbok öfver svenska

medeltidsspråket, Berlingska Boktryckeriet AB. Lund.

Winkler, W. E., 1990. “String Comparator Metrics and

Enhanced Decision Rules in the Fellegi-Sunter Model

of Record Linkage”, in Proceedings of the Section on

Survey Research Methods. American Statistical

Association, pp. 354–359.

NLPinAI 2020 - Special Session on Natural Language Processing in Artificial Intelligence

458