Straight to the Point - Evaluating What Matters for You:

A Comparative Study on Playability Heuristic Sets

Felipe Sonntag Manzoni

1,2 a

, Tayana Uchôa Conte

1

, Milene Selbach Silveira

3

and Simone Diniz Junqueira Barbosa

4

1

Instituto de Computação, Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

2

SIDIA Instituto de Ciência e Tecnologia, Validation Team, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

3

Escola Politécnica, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

4

Departamento de Informática, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Keywords: Playability, Heuristic Sets, Playability Assessment, Game Assessment, Comparative Empirical Studies.

Abstract: Background: Playability is the degree by which a player can learn, control, and understand a game. There

are many and different Playability evaluation techniques that can evaluate different and numerous game

aspects. However, there is a shortage of comparative studies between these proposed evaluation techniques.

These comparative studies can assess whether the evaluated techniques can identify playability problems with

a better cost-benefit ratio. Also, these studies can show game developers the evaluation power that a technique

has in comparison to others. Aim: This paper aims to present and initially evaluate CustomCheck4Play, a

configurable heuristic-based evaluation technique that can be suited for different game types and genres. We

evaluate CustomCheck4Play, assessing its efficiency and effectiveness in order to verify if

CustomCheck4Play performs better than the compared heuristic set. Method: We have conducted an

empirical study comparing a known literature heuristic set and CustomCheck4Play. The study had 54

participants, who identified 49 unique problems in the evaluated game. Results: Our statistical results

comparing both evaluation techniques have shown that there was a significant statistical difference between

groups. Efficiency (p-value = 0.030) and effectiveness (p-value = 0.004) results represented a statistically

significant difference in comparison to the literature heuristic set. Conclusions: Overall, statistical results

have shown that CustomCheck4Play is a more cost-beneficial solution for the playability evaluation of digital

games. Moreover, CustomCheck4Play was able to guide participants throughout the evaluation process better

and showed signs that the customization succeeded in adapting the heuristic set to suit the evaluated game.

1 INTRODUCTION

The development of digital games, their use, and,

subsequently, their evaluation, grow every year, with

new evaluation methods and developed studies

(Politowski et al., 2016). For game developers,

playability is considered a paramount quality

criterion (Pinelle et al., 2008a), where the playability

definition is a means to evaluate existing interactions

and relationships between the game and its design.

These interactions are translated into every action,

decision making, pausing the game, thinking a

strategy or play, coordinating with team members,

and more. Pinelle et al. (2008a) defined the quality of

these interactions as: “the degree by which a player is

able to learn, control, and understand a game.”

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2259-6744

As a paramount quality criterion, we need to

support game development companies in conducting

better playability evaluations. Different authors have

proposed solutions for the evaluation of playability in

general games in order to support game development

companies (Barcelos et al., 2011; Desurvire et al.,

2004; Desurvire and Wiberg, 2009; Korhonen and

Koivisto, 2006; Korhonen et al., 2009; Manzoni et al.,

2018). However, the literature lacks comparative

studies between these proposed heuristic sets and

previously proposed techniques in the literature.

Comparative studies can show differences, gaps, and

positive aspects of each proposed solution that

otherwise would not be evaluated by exploratory and

non-comparative validation studies (Bargas-Avila

and Hornbæk, 2011).

Manzoni, F., Conte, T., Silveira, M. and Barbosa, S.

Straight to the Point - Evaluating What Matters for You: A Comparative Study on Playability Heuristic Sets.

DOI: 10.5220/0009381304990510

In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2020) - Volume 2, pages 499-510

ISBN: 978-989-758-423-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

499

Literature playability heuristic sets often make

similar design decisions that can lead to some

problems: (1) Heuristic sets are either too large or too

specific for a type of game (Korhonen et al., 2009);

(2) The number of heuristics has a directimpact on the

memorization of participants (Barcelos et al., 2011);

(3) Described heuristics often use technical language

that cannot be easily understood by all evaluators

(González-Sánchez et al., 2012). Comparative studies

can help game developers to know which proposed

heuristic set to choose from in which situation.

Furthermore, comparative studies can show different

evaluator needs throughout evaluation sessions,

which, probably, single one-way study scenarios

would not identify (Korhonen et al. 2009).

The work of Barcelos et al. (2011), one of the

comparative studies available in the literature,

showed that, when comparing a large heuristic set

(approximately 40 heuristics) with a reduced heuristic

set (with 10 to 15 heuristics), there is no statistically

significant difference between set sizes for cost-

benefit purposes. In a more recent work, Manzoni et

al. (2018) showed that using non-expert evaluators

does not change the efficiency or effectiveness of

evaluation sessions (when the set is developed for

them). However, they have discussed that using non-

expert evaluators can impact the evaluation costs as

non-expert evaluators are more available than

playability experts. Also, Korhonen et al. (2009), in a

comparative study, discovered patterns and

suggestions for the development of playability

heuristic sets. These results could only be verified and

gathered because of the comparative analyses

between proposed heuristic sets.

To face some of the challenges uncovered by

comparative studies conducted in literature, we set

out to develop a solution that can support game

development companies in evaluating playability.

Also, we intend to identify differences between the

proposed solution and the literature heuristic set and

how to improve the proposed solution to better suit

game development companies. This proposed

solution is an attempt to support the challenges

uncovered in the literature; we have proposed the

CustomCheck4Play evaluation technique as a

configurable heuristic set that can adapt itself to

different game genres.

However, just proposing a solution is not enough

to identify its quality and cost-benefit ratio for its

users. It is necessary to verify the quality of the

proposed technique and its cost-benefit ratio in

comparison to existing techniques and how they

differ, supporting their choice or not by users and

developers. As such, we have conducted a

comparative study with another heuristic set from the

literature (Barcelos et al., 2011). With this

comparative empirical study, we intend to identify

differences and gaps in the proposed solution and

how it can be improved to suit development

companies better. Also, we will be able to identify

which evaluation method is better and guide

evaluators and developers to choose one of the

compared methods. This study should be able to

indicate if CustomCheck4Play is a valid solution for

digital games playability evaluations and how it can

further improve in relation to the state of the art.

Statistical results from the comparative empirical

study have shown that the proposed set can help

evaluate playability problems more efficiently and

effectively than the compared set. These results

indicate that CustomCheck4Play is a valid solution

for the evaluation of playability problems in digital

games. The paper discusses the contributions of this

study for the community and participants' perception

of the use of the heuristic set.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2

presents the background and related work for this

paper, Section 3 presents an overview on the

CustomCheck4Play evaluation technique and how to

use it, Section 4 presents the empirical comparison

study with CustomCheck4Play, Section 5 presents

the quantitative results on the empirical study

conducted, Section 6 presents the qualitative results

on the empirical study conducted, Section 7 presents

threats to the validity of the conducted empirical

study, and Section 8 presents the overall conclusions

of this paper.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Playability

Nacke et al. (2009) defined a general concept for the

playability of games and differences between

playability and player experience. According to their

definition, playability is related to the evaluation of

existing interactions and relationships between the

game and its design. Moreover, it evaluates whether

information needed by gamers is presented and

whether the game design is in accordance with the

type and genre of the evaluated artifact. Similarly, the

player experience tends to evaluate relations between

users and the game (Nacke et al., 2009). Playability is

a predominant quality criterion for game

development, as it can identify interaction and design

issues throughout the game development (González-

Sánchez et al., 2012). By evaluating the playability of

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

500

games and discovering these issues in earlier

development phases, it is possible to decrease costs

with changes to the design and with game patches

(Manzoni et al., 2018). Meanwhile, playability

evaluations can improve the overall quality of games,

increasing the users’ acceptance of the game from the

beginning (González-Sánchez et al., 2012).

2.2 Related Work

There is much ongoing research in the field of

heuristic sets for evaluating playability in different

game aspects (Barcelos et al., 2011; Desurvire et al.,

2004; Desurvire and Wiberg, 2009; Korhonen and

Koivisto, 2006; Korhonen et al., 2009; Korhonen,

2016; Manzoni et al., 2018; Pinelle et al., 2008a).

These studies have aimed to develop a unique and

standardized heuristic set that can evaluate every

game type and genre. Pinelle et al. (2008b)

demonstrated that, for different game types and

genres, differences in aspects, mechanics, and

gameplay need to be considered for the evaluation of

the game’s playability. Therefore, not all of these

heuristic sets may be able to evaluate all of the

necessary aspects of each game. Due to this broad

approach, heuristic sets tend to be very large, and with

generalized heuristics that tend to evaluate many

different aspects.

Korhonen and Koivisto (2006) proposed Mobile

Heuristics, a heuristic set based on the assumption

that there are unique characteristics to the mobile

aspect of games. The authors have conducted a

comparative experiment between their work and a

heuristic set found in the literature. In another work,

Korhonen et al. (2009) presented the results of this

comparative experiment, which showed strengths and

weaknesses of the set so that they could identify

patterns for producing sets on the literature.

Desurvire et al. (2004) developed a heuristic set

called HEP (Heuristic Evaluation for Playability),

containing 43 heuristics. The heuristics are classified

into four categories: Game Play, Game Story,

Mechanics, and Usability. These categories aimed to

guide participants during the evaluation, but

participants have identified that the set became too

large to be memorized, even though those categories

could guide them. In a later work, Desurvire and

Wiberg (2009) have developed an evolution to the

HEP heuristic set, which they called PLAY

(Heuristics for Playability Evaluation). The new set

contains 50 heuristics classified into several

categories. Even though the categorization of the set

helped evaluators to find specific heuristics, the large

number of heuristics in the set could still represent

difficulties in memorization and confuse evaluators

throughout evaluation sessions.

Also, Desurvire and Wiberg (2008) have

developed a guideline for evaluating and developing

better initial tutorial levels on games. The ‘Game

Approachability Principles’ – GAP (Desurvire and

Wiberg, 2015) is a guideline with ten major principles

that guide evaluators for better-developing tutorials

and first learning levels on games, especially for

casual games. Furthermore, GAP can be used as (1) a

Heuristic Set; (2) as an adjunct to Usability

Evaluations; (3) and as a proactive checklist of

principles in beginning conceptual and first learning

level tutorial design. GAP is suited for the concept of

Game Approachability, a concept that evaluates how

easily gamers can learn and understand the game.

Pinelle et al. (2008a) have developed a heuristic

set for evaluating game-based usability problems by

analyzing game reviews from six major types of

games. However, their set is directed at evaluating

usability aspects instead of playability issues. Their

work was able to identify important usability aspects

that need to be evaluated in different game types, and

which are usually overlooked in game development

phases. In another work, Pinelle et al. (2008b)

analyzed how each game problem differs from each

other in each collected game genre. Their findings

were that, for each game genre, gamers report

different types of problems and that there is a

significant statistical difference in problems reported

for each genre of game. For example, Role Playing

Games (RPG) require much “Training and Help”

during its gameplay, while for Action games this

aspect has almost no influence on gamers. These

results led the authors to point out that heuristic sets

that consider differences in game genres and types

could help evaluators on the evaluation process.

Differences in game genres and types can represent

different evaluated heuristics and needs for the

evaluation process.

Barcelos et al. (2011) have developed a heuristic

set based on previous works developed by Desurvire

and Wiberg (2009). Their initial step was to

understand that the biggest problem with this type of

approach was the size of the set. The proposed set

intended to be smaller than heuristic sets in the

literature, and they expected that a smaller set could

improve the efficiency and effectiveness of game

evaluations. However, they have not proved that the

total number of heuristics in the set has any influence

on the evaluation process.

Manzoni et al. (2018) have developed a heuristic

set called NExPlay, which aimed to improve the

efficiency and effectiveness of playability

Straight to the Point - Evaluating What Matters for You: A Comparative Study on Playability Heuristic Sets

501

evaluations. The set focused on the understanding of

heuristics by non-expert evaluators, as well as size

and categorization. The set comprises 19 heuristics

grouped into three categories (Game Play, Usability,

and Mechanics). The heuristic set was tested in a

comparative study with the heuristic set developed by

Barcelos et al. (2011). Results showed that NExPlay

is suitable for playability evaluation at different

stages of game development, using participants with

different levels of knowledge, but it could be further

improved.

Even though Pinelle et al. (2008b) identified that

different game genres and types require different

aspects to be analyzed in playability terms, none of

the aforementioned solutions have satisfied this need.

A solution based on evaluating each type and genre

of games as a special case with different heuristics

could improve the cost-benefit ratio of evaluations.

With such a customizable evaluation, heuristic sets

could be smaller and specific to the game under

evaluation, making it easier for evaluators to identify

issues (Pinelle et al., 2008b). Also, few studies have

compared their proposal with existing approaches in

the literature (Barcelos et al., 2011; Korhonen et al.,

2009; Manzoni et al., 2018). As such, there is little

discussion on gaps, opportunities for improvement,

and good features of these proposed heuristic sets and

how they have contributed to increasing the

knowledge in this research topic.

However, we can draw some knowledge from the

performed comparative studies. Even though

Barcelos et al. (2011) did not find a statistical

difference when using smaller heuristic sets, their

qualitative analysis showed that shorter sets influence

memorization and ease of identifying problems. Also,

the authors discuss that with this shorter set, feedback

on game problems can be made consistently and

quicker, as evaluators can remember heuristics for a

longer period of time. Korhonen et al. (2009)

identified certain characteristics in literature heuristic

sets that can help authors in the process of developing

better solutions. Also, their work identified specific

characteristics that need to be evaluated in the field of

mobile games. Even tough Manzoni et al. (2018) did

not find a statistically significant difference between

their proposed heuristic set and the compared

literature heuristic set, their qualitative results showed

that non-expert evaluators can correctly, efficiently,

and effectively evaluate digital games when the

heuristic set is developed for them.

More comparative studies are needed to identify

different situations when, for example, heuristic sets

are developed specifically for a type and genre of

game. Mainly, the empirical study developed in this

paper intends to identify the impact that heuristic sets

explicitly developed for different types of games has

on the evaluation process and its results.

3 THE CustomCheck4Play

EVALUATION TECHNIQUE

Evaluating games based on their type and genre can

greatly benefit the evaluation process by reducing the

time needed to perform the evaluation. As defined by

Pinelle et al. (2018b), when evaluating games consi-

dering their specific types and genres, fewer heuristics

are needed, as heuristics on the set are more suitable to

the game being evaluated. As heuristics are more

specific, and fewer heuristics are needed, evaluators

can find and remember heuristics more easily. In this

sense, we developed CustomCheck4Play, mainly

considering these benefits.

CustomCheck4Play is an inspection technique

based on a heuristic set for the assessment of the

playability of digital games. Heuristic-based

evaluation techniques for playability tend to become

very time-consuming and require specialists to

conduct the evaluation (Korhonen et al., 2009). By

contrast, CustomCheck4Play aims to have a shorter

set of heuristics (specifically adapted to each type of

game), and it does not require a playability specialist

to conduct the evaluation process.

CustomCheck4Play aims to evaluate specific types

and genres of games by customizing the set of

heuristics used in each evaluation session.

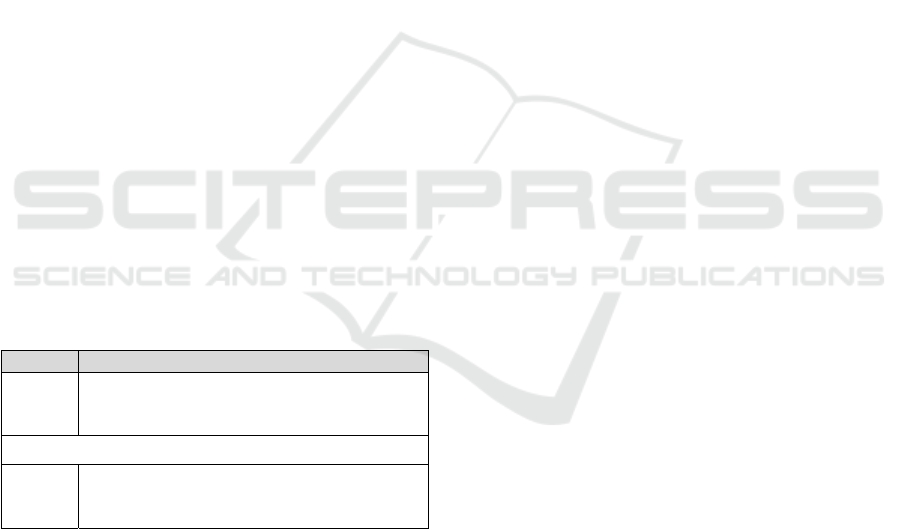

Table 1: Categories for CustomCheck4Play heuristics.

ID Heuristics Categories

1

Introduction

2

Character Presentation

3

Gameplay Introduction

4

Gameplay Development

5

Storytelling

6

Gameplay Evolution

7

Game Pause

8

Context Helps and Error Recovery

9

Difficulty and Progressive Levels

10

Configurability and Menus

CustomCheck4Play comprises a set of heuristics

specifically developed to close this gap. The set aims

to verify whether the developed game aspects are in

line with the expected aspects defined by the game

type and genre. Following this discussion and the

literature gaps, we designed CustomCheck4Play to

satisfy four specific goals, presented in Table 2.

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

502

Table 2: CustomCheck4Play goals, aspects and motivations to develop the heuristic set.

ID Goal Developed Aspect Motivation

1

Reduce evaluation

costs and time.

CustomCheck4Play can be

applied by non-experts.

Non-expert evaluators are more available and cheaper, while

not representing a loss in efficiency and effectiveness.

2

Memorization of

heuristics.

It has a reduced number of

heuristics.

As lower, the number of heuristics is, easier evaluators can

remember past heuristics and apply them in the future.

3

Support easy

understanding and

comprehension.

CustomCheck4Play has

support sentences for

specific heuristics.

Support sentences are a secondary way to describe the

heuristic and improve evaluators' understanding of them.

4

Customizable for

specific game

types.

CustomCheck4Play can be

customized accordingly to

the evaluated game type.

Heuristic sets specifically developed for a type of game can

easily identify all the needed game aspects and problems.

In order to satisfy Point 4, regarding the

development of a modular heuristic set,

CustomCheck4Play comprises ten categories, which

help with the set customization. When customizing

the set, we evaluate each category in comparison to

the game type aspect in order to better understand if

the category heuristics are needed. If a category does

not represent needed game aspects, then its heuristics

are ruled out. Heuristics categories are listed in Table

1. Table 3 presents a subset of the CustomCheck4Play

heuristics, and the full set is available in a Technical

Report (Manzoni et al., 2020a).

Table 3: A subset of the CustomCheck4Play heuristics.

N° Heuristics

Introduction

I1

The game has an initial storyline and primary

goal that justifies the player's actions.

I2

The game should present a tutorial to

familiarize the player with mechanics and

gameplay.

…

Configurability and Menus

…

CM35

Controls are expandable for more skillful

players.

To define a suitable set for the evaluated game, we

developed a questionnaire about the game to be

evaluated. Each answer to the questionnaire will

cause the inclusion or exclusion of certain categories

and heuristics in/from the set. The heuristics are

classified into ten different categories, as exemplified

in Table 1, where each category represents a unique

game characteristic. As the categorization of the set

considers game aspects, the customization process

takes into account game aspects in each question.

Thus, each answer on the questionnaire will include

1

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.

fpftech.leapofcat&hl=en

or exclude a category of the set, depending on the

aspects of the game reported by the user. The

questionnaire and its possible answers are available in

the technical report (Manzoni et al., 2020a).

3.1 Example of Use

Figure 1: Screenshots from Leap of Cat tutorial.

Figure 1 presents two screenshots from the initial

tutorial of the game Leap of Cat

1

. Leap of Cat is a

casual game where your main objective is to keep

jumping from platform to platform in order to climb

up the building. However, the initial tutorial

presented in the game does not present all mechanics

and possibilities that the player can use in his

advantage, or the consequences of making mistakes,

or presenting any story that leads us to continue

climbing the building. In this sense, an evaluator

using CustomCheck4Play would be able to identify

these problems guided by heuristics I1 & I2 from the

Introduction section of the set, presented in Table 3.

Straight to the Point - Evaluating What Matters for You: A Comparative Study on Playability Heuristic Sets

503

4 EMPIRICAL STUDY

The main goal of this study was to comparatively

investigate the cost-benefit of using

CustomCheck4Play instead of another heuristic set

from the literature. To achieve this goal, we

developed the following research questions:

RQ1 Is the CustomCheck4Play evaluation

technique more efficient and effective than the

compared set?

RQ2 What is the evaluators’ perspective on the

use of CustomCheck4Play?

4.1 Heuristic Set for Comparison

For this comparison study, we chose the heuristic set

proposed by Barcelos et al. (2011) because their

developed set aims at verifying whether shorter sets

can be more cost-beneficial to playability evaluations.

In some aspects, this objective relates to the goal of

evaluating games accordingly to their types, reducing

the number of heuristics. Moreover, the developed set

considers different heuristic sets from the literature,

and we hypothesize that, in this way, the heuristic set

can cover the main and various game aspects

proposed by different authors.

Table 4 presents a subset of their heuristics

(Barcelos et al., 2011), and the complete, translated,

heuristic set is available in a Technical Report

(Manzoni et al., 2020a).

Table 4: A subset of the heuristics proposed by Barcelos et

al. (Manzoni et al., 2020a).

N° Heuristics

H1

The controls should be clear, customizable,

and physically comfortable; their response

actions must be immediate.

…

H18

Artificial intelligence should present

unexpected challenges and surprises for the

player.

4.2 Participant Selection

We have selected students who were undertaking

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) courses, as they

would guarantee that participants had a minimum

knowledge about heuristic evaluations or games.

Also, undergraduate students are non-expert

playability evaluators in their majority, which would

also reflect the population for whom the technique is

intended. We conducted the study in two rounds, in

two different institutions, to reach a more diversified

and wider population:

• The first round was composed of 28

undergraduate students of Computer Science from

UFAM (Federal University of Amazonas).

• The second group was composed of 26

undergraduate students of Software Engineering

from PUC-RS (Pontifical Catholic University of

Rio Grande do Sul).

To balance participants between groups that

would use each evaluation technique, we applied a

characterization questionnaire. The questionnaire

included two questions, first regarding levels of

expertise in games in general terms. The question was

subdivided into three possible answers: (i) “Heavy

Player (persons who know a lot about many different

types of games and dedicate a special time of their

lives to play those games)”; (ii) “Casual Player

(persons who like a specific game type, but do not

dedicate much time to it)”; (iii) “Do not like games”.

For the second question, we asked whether

participants had any prior knowledge or experience

with game development. This question had four

different possible answers: (i) “Yes, I have already

worked in game development projects in industry”;

(ii) “Yes, I have already worked in game development

projects in academia”; (iii) “Yes, but only by myself

as curiosity or hobby”; (iv) “No, I have not had any

prior knowledge or experience with game

development.”

All participants had prior knowledge in Software

Engineering and were taking an HCI course. Every

participant filled out a characterization questionnaire

and was randomly assigned to one of the groups

(following the principle of random design),

respecting their level of knowledge as self-reported

on the questionnaire. Following this process resulted

in round 1 having an equal distribution of 14

participants in the group that used

CustomCheck4Play and 14 participants in the group

that used Barcelos et al.’s heuristic set. In the second

round, we had 11 participants in the group that used

CustomCheck4Play and 15 participants in the group

that used the set proposed by Barcelos et al. In the

analyses of the results, we have considered Set 1 as

the union of the participants from both rounds using

CustomCheck4Play. Likewise, we have considered

Set 2 as the union of the participants from both rounds

using the set proposed by Barcelos et al.

4.3 Game Selection

Every playability assessment process begins with

selecting the game which we aim to evaluate. For this

study, we selected Leap of Cat, a casual game type,

which is the first game produced by a software house,

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

504

a company focused on software and not on game

development. The game presents a simple theme and

story with no further changes throughout its gameplay

or sudden changes to mechanics and storytelling. We

chose Leap of Cat because it is freely available at the

Google Play store for any Android-compatible

device. Moreover, a previous study with this game

produced an oracle list of problems for the game

(Manzoni et al., 2018).

4.4 Experimental Process

We designed this experiment as a one-way study. We

have not selected a cross design because of the

knowledge propagation between the sets’ evaluation

(Wohlin et al., 2012). Before executing the empirical

study, the participants were introduced to

fundamental concepts of playability and the

playability assessment process. We conducted a

training session with all participants in both rounds

using the same training process two days before the

execution of the study. After the training, we

considered that all participants had similar levels of

knowledge of playability and playability assessment.

After the training, we instructed participants to

play the game and to use their given heuristic set to

identify problems in it. We also asked participants to

write down every found problem in a table we

provided (problem specification table), as well as the

heuristic violated in each problem. Moreover,

participants wrote down their initial and final times

on the problem specification table.

Both rounds were made in loco, with the presence

of two researchers. The same instructions were given

in both rounds, limiting the game evaluation session

to two hours. Researchers could only interfere if

participants had not entirely understood the sense of

some words in the instructions. If it referred to the

heuristic set or with the game itself, the researchers

would not interfere. For example, if participants did

not understand the evaluation instruction process, the

researchers could interfere with explaining how to

conduct the evaluation process. However, if

participants had any questions regarding the rules of

the evaluated game or any other aspect related to the

game, the researchers would not interfere. Before the

study began, researchers handed out to each evaluator

the designated heuristic set, the problem specification

table, and some short instructions on what to do.

Each participant conducted his/her game

evaluation individually and wrote down initial and

end times on the table of problem specification. They

have returned all tables with the identified

discrepancies to the researchers at the end of the

evaluation session.

4.5 Data Consolidation

After receiving all problem specification tables, the

researchers created a list of discrepancies with no

duplicates (same problems repeated in different

wordings) from both rounds. Discrepancies were

marked as problems found by participants that still

have yet to be verified by a specialist and

development team to discuss whether it is an actual

problem or just a false-positive (Wohlin et al., 2012).

A false-positive is an issue found by participants that

is in fact intended (Wohlin et al., 2012), not

representing a defect in the game.

The produced list with no duplicated

discrepancies was analyzed by two experts, who

classified every discrepancy as either an actual

problem or as a false-positive. Also, researchers

developed a different table containing individual

initial and final times, number of discrepancies,

number of false positives, and other quantitative

measures. The complete table with all quantitative

data can be accessed at (Manzoni et al., 2020b).

To answer the question “RQ1: Is the

CustomCheck4Play Evaluation Technique more

efficient and effective than the set proposed by

Barcelos?”, we conducted a quantitative analysis of

the collected data. For the quantitative analysis, we

considered as treatments for the independent variable

both employed heuristic sets and, as the dependent

variables, the efficiency and the effectiveness of the

sets. We calculated the efficiency of each participant

as the ratio between the number of defects found and

the time spent evaluating the artifact. We calculated

the effectiveness of each participant as the ratio

between the number of defects found and the total

number of (known) defects in the artifact. This total

number considers all the unique (not duplicated)

problems found on the game in all developed studies.

In practice, the total number of known defects

considers both the defects found in this experiment

and defects found in the study developed and

published by Manzoni et al. (2018). This compiled

list of defects can be found in the published open data

(Manzoni et al., 2020b).

To answer “RQ2: What is the evaluators’

perspective on the use of CustomCheck4Play?”, we

conducted a qualitative analysis. For the qualitative

analysis, we asked each participant to fill out a

questionnaire about their perception of using the

heuristic set.

Straight to the Point - Evaluating What Matters for You: A Comparative Study on Playability Heuristic Sets

505

5 QUANTITATIVE RESULTS

Overall, 49 unique problems were found, considering

both Set 1 (CustomCheck4Play) and Set 2 (Barcelos

et al). In this context, a unique problem is a problem

identified in the game, not considering duplicates and

counted just once. In the first round, participants

using Set 1 found 33 unique problems, and

participants using Set 2 found 21 unique problems. In

the second round of the study, participants using Set

1 found 38 unique problems, and participants using

Set 2 found 28 unique problems. The results and the

corresponding level of each participant are available

as an open-data table that can be checked (Manzoni

et al., 2020b).

The experiment was designed to test the following

hypotheses:

H01: There is no difference in terms of efficiency

when using the CustomCheck4Play heuristic set and

the set proposed by Barcelos et al.

HA1: There is a difference in terms of efficiency

when using the CustomCheck4Play heuristic set and

the set proposed by Barcelos et al.

H02: There is no difference in terms of

effectiveness when using the CustomCheck4Play

heuristic set and the set proposed by Barcelos et al.

HA2: There is a difference in terms of

effectiveness when using the CustomCheck4Play

heuristic set and the set proposed by Barcelos et al.

Table 5 presents the calculated means for

efficiency and effectiveness. Every presented

information is calculated over both rounds of the

empirical study. We have conducted statistical tests

to assess the statistical difference and significance

between the sets under evaluation with respect to

efficiency and effectiveness.

Table 5: Calculated means for the quantitative results.

Sets TP M

AE

(%)

TT

(h)

EF

Set 1

71 8.84 14.98 13.18 5.39

Set 2

49 5.72 9.70 13.68 3.59

Legend: TP – Total Problems; M – Mean Problems per

Participant; AE – Average Effectiveness; TT – Total

Time; EF – Efficiency (Problems/Hour)

We ran a Shapiro-Wilk normality test (Shapiro

and Wilk, 1965) to choose the adequate statistical test

for comparing the samples. As Table 6 shows, the

efficiency variable was not normally distributed, so

we performed a Mann-Whitney (Mann and Whitney,

1946) statistical test with a confidence level α=0.05.

2

https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics

Also, as Table 6 shows, as the effectiveness variable

was normally distributed, we performed a T-Student

(Juristo and Moreno, 2001) statistical test with a

confidence level α=0.05. We performed the statistical

analyses using SPSS Tool

2

.

Table 6: Normality test results for efficiency and

effectiveness.

Efficiency

Shapiro-Wilk

Set p-value

1 - CustomCheck4Play 0.005

2 - Barcelos et al. 0.337

Effectiveness

Shapiro-Wilk

Set p-value

1- CustomCheck4Play 0.252

2 - Barcelos et al. 0.212

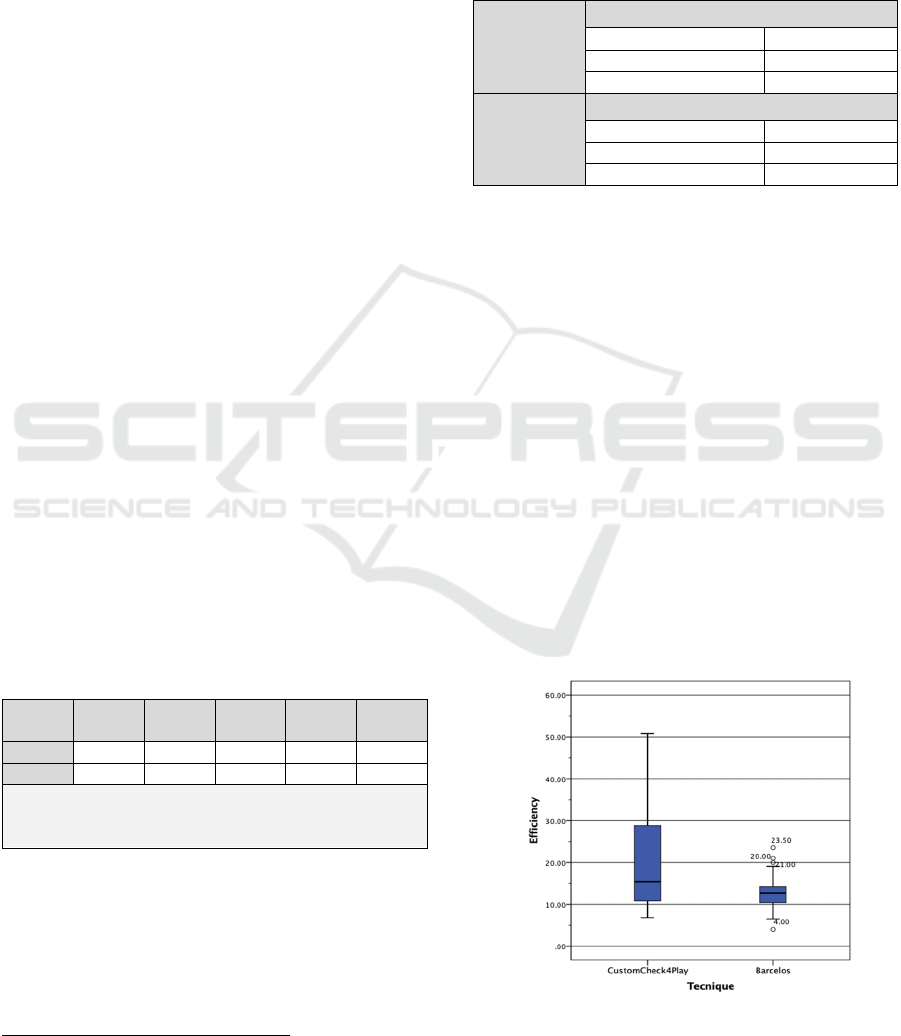

5.1 Efficiency Analysis

Firstly, to visualize the data distribution of the two

sets, we used a boxplot (Cox, 2009). The boxplot for

efficiency is shown in Figure 2. One can observe that

the boxplot for the efficiency shows higher values for

Set 1, but there is a large spread of values, while Set 2

had lower and more concentrated values. The results

of the Mann-Whitney statistical test show that there

is a statistically significant difference between Set 1

and Set 2 (p-value = 0.030). According to these

results, it is possible to reject the null hypothesis

(H01) and accept the alternative hypothesis (HA1).

For Efficiency values, the effect size was d=0.83,

and, considering the scale described by Cohen’s

(Cohen, 1988), this result represents a large

difference between the groups. This means that, for

practical purposes, there is a great advantage in using

Set 1 instead of Set 2 in terms of efficiency, i.e., using

Set 1 one can find problems at a faster pace.

Figure 2: Boxplot for Efficiency values.

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

506

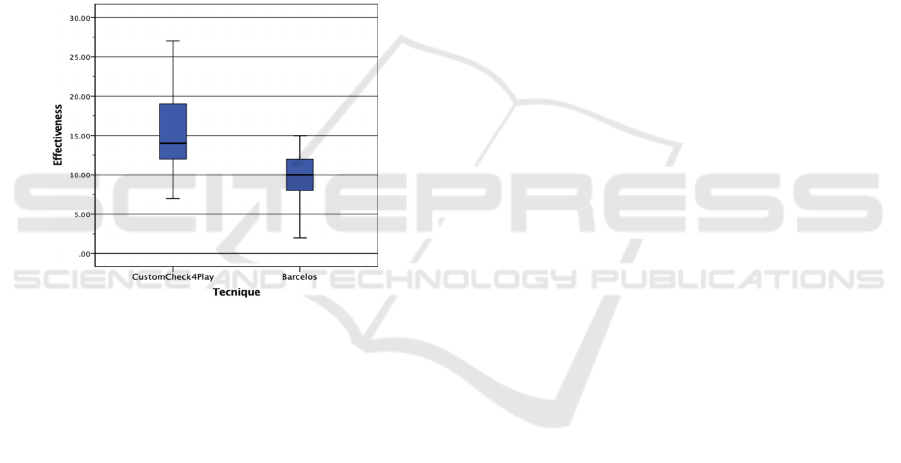

5.2 Effectiveness Analysis

Likewise, a boxplot was used to visualize the data

distribution of the two sets (Cox, 2009). The boxplot

for effectiveness is shown in Figure 3. One can

observe that the boxplot for the effectiveness shows

higher values for Set 1, with a slightly wider spread

than Set 2. The results of the T-Student statistical test

show a statistically significant difference between

Set 1 and Set 2 (p-value = 0.004). According to these

results, it is possible to reject the null hypothesis

(H02) and accept the alternative hypothesis (HA2).

For Effectiveness values, the effect size was d=1.21,

and, considering the scale described by Cohen’s

(Cohen, 1988), this result represents a large

difference between groups. In practice, there is a large

gain in the number of identified problems when using

Set 1 instead of Set 2.

Figure 3: Boxplot for Effectiveness values.

6 QUALITATIVE RESULTS

Participants filled out a questionnaire after they had

evaluated the game with CustomCheck4Play so that

we could evaluate their perception of using the

heuristic set. For the analysis of these questionnaires,

the researchers read individual questionnaires and

wrote down uncovered problems and general

perceptions. These problems and general perceptions

are described and grouped in sections accordingly to

the treated issue or perceptions. The qualitative

results analyzed from the questionnaires are

presented below in regard only to the

CustomCheck4Play participants’ point of view. We

intended to evaluate just the qualitative side of

CustomCheck4Play because the set proposed by

Barcelos has already been evaluated in a different

study that considered qualitative aspects for it

(Barcelos et al., 2011).

6.1 Understanding of the Heuristics

and Heuristic Specificity

Nineteen participants, out of the twenty-five, that

used CustomCheck4Play, declared that they had no

difficulties in understanding what each heuristic

meant and that heuristics were clearly written:

“I had no difficulties in understanding the

heuristics from the given heuristic set; all

sentences were clearly written and easy to

associate with game problems.” – P08.

P06 had a specific difficulty in understanding the

heuristic H25. Analyzing H25, which talks about

pausing the game and returning to the same point later

(as a ‘save state’), we hypothesize that the

participant's difficulty occurred because the selected

game does not have this function. The selected game

cannot stop and return to it in a later moment at the

same state:

“I’ve found some difficulty in understanding

and evaluating the heuristic H25 for the selected

game. Moreover, the rest of the heuristics for the

set are well written and I haven’t had any

difficulty understanding them.” – P06.

Two participants, P07 and P14, had difficulties

with heuristics H3, H8, and H26. In heuristic H3, P07

claimed that the terminology used in one of the words

could mislead participants during evaluation. For H8

and H26, the participants did not specify the difficulty

they had. Regarding H26, which evaluates the

mechanics of the controls used in the game, we

hypothesize that the difficulty occurred because the

selected game has only one mechanic, which does not

vary during play. And, regarding H8, which evaluates

how easily players can find information about the

game state, we hypothesize that the difficulty

occurred because the game does not provide extra

lives nor displays the current score on the screen.

P20 claimed that some heuristics were too specific

for the evaluated game and that others were too

general. However, it has not referenced which

heuristics motivated this comment. P24 explained

that the only difficulty they encountered was with the

first page of the handed-out heuristic set, in which all

heuristic set categories were displayed. P25 claimed

he had difficulties in the understanding of heuristics

but did not specify why or where and with which

heuristics.

“Yes, I had some difficulties understanding

some heuristics because some were too specific,

and others were too broad.” – P20.

“I only had some difficulty to understand that

the first page of the heuristic set only presented

Straight to the Point - Evaluating What Matters for You: A Comparative Study on Playability Heuristic Sets

507

heuristic categories and not the actual

heuristics.” – P24.

6.2 Heuristics Support Sentences

Support sentences had some divergent opinions and

different situations that could be evaluated from the

participants' points of view. The support sentences

were reported to have been used by two participants

in two situations: (i) when the support sentence was

used to understand better a heuristic; and (ii) when the

support sentence was used to decide between similar

heuristics.

“I have not found difficulties, and when I had,

the support sentence was there to explain in

different wording.” – P12.

“A positive point is the support sentence, that

when I was in doubt of which heuristic to use, the

support sentence helped me to choose.” – P11.

For the majority of the participants, the heuristic

support sentences were not used at all or were not

even perceived. In one case, the participant stated that

support sentences made the heuristic set too wordy:

“A negative point is that the heuristic set is too

wordy sometimes, especially when heuristics had

a support sentence with it.” – P25.

6.3 Size of the Heuristic Set and

Missing Heuristics

P03 complained that they missed more heuristics

about the main character and its mechanics. Another

participant, P04, complained about the lack of pure

usability-based heuristics, which could evaluate

problems of consistency and navigation. Also, P18

asked for the heuristics about social networks and

content sharing.

“I would like some more heuristics about the

main character and its mechanics. In the

evaluated game, I’ve encountered two problems

that I have matched with more than one heuristic

so that they would complement each other.” –

P03.

“I’ve missed heuristics that evaluated things

like: navigation pattern, consistency, the game

didn’t have advertising, but still it has a button for

ad removal, I would’ve signaled it as a problem

but there was nothing to associate with it.” – P04.

“I’ve missed a heuristic for the evaluation of

social network connection and content sharing

from the game itself.” – P18.

Regarding heuristic set size, participants P15,

P22, and P24 argued that the set contained heuristics

that were either too general or that could not be

evaluated in the selected game because of their

simplicity.

“The heuristic set does not need new

heuristics; however, not all heuristics could be

evaluated in this game (maybe they would be

evaluated in a bigger and more complex game).”

– P24.

7 THREATS TO VALIDITY

Every empirical study has some threats to its validity,

which need to be identified so that they can be

handled throughout the experimental process. The

associated threats to this work are separated into four

categories: conclusion validity, internal validity,

external validity, and construct validity (Wohlin et

al., 2012).

Internal Validity: Regarding time measurement,

there is the risk of measurement errors made by the

participants during the evaluation. This threat could

have a significant impact on our results from the first

round, as we did not have any control over how

participants recorded time or whether the recorded

time was correct. In an attempt to control this threat,

the provided material had distinct places where

participants needed to record their times, and this

specific step was mentioned during the training

phase. With regard to the given training, it could have

side effects during the inspection. It can happen if the

training given for participants of Set 1 was better or

worse than the training given for participants of Set 2,

or between round one and two. To mitigate this threat,

the same training was given for participants from

Set 1 and Set 2, as well as for rounds one and two.

Moreover, the given training used only simple

examples, which were not from either Set 1 or Set 2,

and which were not related to the assessed game.

Lastly, regarding knowledge levels, the data was self-

reported: the participants themselves filled out the

questionnaire without any independent confirmation

of their assessment.

External Validity: For generalization purposes,

the game used for the evaluation, “Leap of Cat,” does

not represent all types of existing games. Moreover,

the study was made in an academic environment,

simulating an evaluation in industry. However,

participants of this study represent the targeted

audience for our set as non-experts in playability and

gamers in general.

Construct Validity: For this type of threat, we

considered the definition of effectiveness and

efficiency used in this study. Such indicators are

widely used in the literature for this type of study and

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

508

we adopted the same definition as these other studies

in the literature (Korhonen and Koivisto, 2006;

Valentim et al., 2015).

Conclusion Validity: The number of

participants, for the purposes of statistical analysis,

was sufficient to validate our results. However, this

study had a shortage of participants with low levels of

knowledge in games and high levels of knowledge in

game development. Because of this, we cannot reach

further conclusions regarding the analysis based on

knowledge levels.

8 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

We presented in this paper a comparison study

between CustomCheck4Play and a heuristic set from

literature (Barcelos et al., 2011). Below, developed

research questions for this study are answered and

discussed.

Regarding RQ1 (Is the CustomCheck4Play

Evaluation Technique more efficient and effective

than the set proposed by Barcelos?), as statistical

results have shown, CustomCheck4Play is more

efficient and effective than the set proposed by

Barcelos et al. in this specific tested scenario with the

selected game for the study. Also, the effect size of

both variables was considered as representing a large

difference between used techniques. This means that

CustomCheck4Play can find more problems in a

faster pace than the literature compared heuristic set

in the type and genre of game tested in this study.

Considering these results, CustomCheck4Play can be

considered a valid option for the evaluation of

playability problems in digital games as it is more

cost-beneficial in the evaluation of specific type and

genres of games.

Regarding RQ2 – “What is the evaluators’

perspective on the use of CustomCheck4Play?”, the

participants’ perception was shown in Section VI and

are further discussed and resumed here:

• We were able to identify from the participants’

phrases that there was no major category missing

for the evaluation of the proposed game.

• We were able to identify that participants have

missed heuristics regarding the main character,

navigation patterns, consistency, and social

network interactions.

• Participants perceived CustomCheck4Play to be

easy to use and understand, as the participants

have not discussed any major difficulty with the

heuristics provided by the evaluation technique

(out of 25 participants, 20 believed that the

evaluation technique was easy to use and

understand).

• Support sentences could help participants to

better understand or choose heuristic from the set

in some situations, but they were mostly

overlooked.

Playability inspections are essential for well-

designed games. They evaluate how the game

presents itself to general users and how one could

improve it with better design and interaction

mechanisms. CustomCheck4Play helps at this point,

as it can be customized to support the evaluation of

every type of game. As it was devised to be used by

both experienced and inexperienced evaluators, it

may also reduce costs by reducing the need for

experts.

As future works, a study to understand how game

developers would classify the identified problems is

needed. With this information, we could include a

severity scale for the problems identified during

assessments. More comparative results are needed,

with different techniques and different types and

genres of games, in order to fully understand the

benefits of using CustomCheck4Play as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the financial support granted

by SIDIA Science and Technological Institute, CNPq

through the process numbers 311316/2018-2,

423149/2016-4, 311494/2017-0, 204081/20181/ PDE

and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher

Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) through the

Financial Code 001 and the process number

175956/2013. We would also like to thank all the

participants who voluntarily made available some

time to participate in the empirical study presented in

this paper.

REFERENCES

Barcelos, T. S., Carvalho, T., Schimiguel, J., & Silveira, I.

F. (2011). Comparative analyses of heuristics for the

evaluation of digital games. In IHC+CLIHC’11, 10th

Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing

Systems and the 5th Latin American Conference on

Human-Computer Interaction. Brazilian Computer

Society, 187-196. (in Portuguese).

Bargas-Avila, J. A., & Hornbæk, K. (2011). Old wine in

new bottles or novel challenges: a critical analysis of

empirical studies of user experience. In Proceedings of

Straight to the Point - Evaluating What Matters for You: A Comparative Study on Playability Heuristic Sets

509

the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems. ACM, 2689-2698.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the

behavioral sciences. (2nd ed. – chapter 3). Hillsdale,

NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Cox, N. J. (2009, September). Speaking Stata: Creating and

varying box plots. In Annals of The Stata Journal, 9 (3),

478-496. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1536867X090090

0309

Desurvire, H., Caplan, M., & Toth, J. A. (2004, April).

Using heuristics to evaluate the playability of games. In

CHI EA ’04: CHI ’04 Extended Abstracts on Human

Factors in Computing Systems. ACM Press.

https://doi.org/10.1145/985921.986102

Desurvire, H., & Wiberg, C. (2008). Evaluating user

experience and other lies in evaluating games. In

CHI’08: Workshop on Evaluating User Experiences in

Games from the Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems. ACM Press.

Desurvire, H., & Wiberg, C. (2009). Game usability

heuristics (PLAY) for evaluating and designing better

games: The next iteration. In OCSC’09, International

Conference on Online Communities and Social

Computing – Part of the LNCS, 5621. Pags. 557-566.

Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02774-

1_60

Desurvire, H., & Wiberg, C. (2015, June). User Experience

Design for Inexperienced Gamers: GAP—Game

Approachability Principles. In: Bernhaupt, R. (eds)

Game User Experience Evaluation – Human–

Computer Interaction Series book (HCIS). Springer,

Chap. 8, 131-148. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-

15985-0_8

Juristo, N., & Moreno, A. M. (2010, December). Basics of

Software Engineering Experimentation (1

st

Edition).

Springer Publishing Company.

Korhonen, H., & Koivisto, E. M. I. (2006, September).

Playability heuristics for mobile games. In MobileHCI

’06: Proceedings of the 8

th

Conference on Human-

Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and

Services. ACM Press. 9 -16. https://doi.org/10.1145/

1152215.1152218

Korhonen, H., Paavilainen, J., & Saarenpää, H. (2009,

September). Expert review method in game

evaluations: comparison of two playability heuristic

sets. In MindTrek ’09: Proceedings of the 13

th

International MindTrek Conference: Everyday life in

the ubiquitous era. ACM Press. 74 – 81. https://doi.org/

10.1145/1621841.1621856

Korhonen, H. (2016). Evaluating playability of mobile

games with the expert review method [M. Computer

Science thesis, Tampere University]. Tampere

University Research Repository.

https://trepo.tuni.fi/handle/10024/99584

Mann, H. B., & Whitney, D. R. (1947). On a Test of

Whether one of Two Random Variables is

Stochastically Larger than the Other. In Annals of the

Journal of Mathematical Statistics, 18 (1), 50 - 60.

https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177730491

Manzoni, F. S., Ferreira, B. M., & Conte, T. U. (2018).

NExPlay – Playability Assessment for Non-experts

Evaluators. In ICEIS ’18: Proceedings of the 20

th

International Conference on Exnterprise Information

Systems - Volume 2, 451-462. SCITEPRESS.

https://doi.org/10.5220/0006695604510462

Manzoni, F. S., Conte, T. U., Silveira, M. S., & Barbosa, S.

D. J. (2020a). Playability Heuristic Set Comparative

Study: Support Material for CustomCheck4Play.

Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8044523

Manzoni, F. S., Conte, T. U., Silveira, M. S., & Barbosa, S.

D. J. (2020b). Collection Results for the Comparative

Study of CustomCheck4Play. [Dataset]. Figshare.

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8044439

Nacke, L., Drachen, A., Kuikkaniemi, K., Niesenhaus, J.,

Korhonen, H. J., Hoogen, W. M. van den, Poels, K.,

IJsselsteijn, W. A., & Kort, Y. A. W. de. (2009,

September). Playability and player experience research.

In DiGRA ’09: Proceedings of DiGRA - Breaking New

Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and

Theory. DiGRA Digital Library.

Pinelle, D., Wong, N., & Stach, T. (2008a, April). Heuristic

evaluation for games: usability principles for

videogames design. In CHI ’08: Proceedings of the

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems. ACM Press.

Pinelle, D., Wong, N., & Stach, T. (2008b). Using genres to

customize usability evaluations of video games. In

Proceedings of the 2008 Conference on Future Play:

Research, Play, Share. ACM Press.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1496984.1497006

Politowski, C., Vargas, D. de, Fontoura, L., & Foletto, A.

(2016). Software Engineering Processes in Game

Development: a Survey about Brazilian Developers. In

SBGames ’16: XV Brazilian Symposium on Games and

Digital Entertainment. SBC.

González-Sánchez, J. L., Vela, F. L. G., Simarro, F. M., &

Padilla-Zea, N. (2012). Playability: Analyzing user

experience in video games. In Journal of Behavior &

Information Technology (31). Taylor & Francis Online.

Shapiro, S. S., & Wilk, M. B. (1965). An Analysis of

Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples), (52,

3), 591–611. JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/2333709.

Valentim, N., Conte, T., & Maldonado, J. (2015).

Evaluating an Inspection Technique for Use Case

Specifications Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis. In

ICEIS ’15: Proceedings of the 17th International

Conference on Enterprise Information Systems.

SCITEPRESS.

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., Höst, M., Ohlsson, M., Regnell,

B., & Wesslén, A. (2012). Experimentation in Software

Engineering. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (1

st

edition).

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

510