NatureCollections: Can a Mobile Application Trigger Children’s

Interest in Nature?

Saba Kawas

1

, Jordan Sherry-Wagner

3

, Nicole S. Kuhn

1

, Sarah K. Chase

2

, Brittany Bentley

4

,

Joshua J. Lawler

2

, and Katie Davis

1

1

The Information School, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, U.S.A.

2

School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, U.S.A.

3

College of Education, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, U.S.A.

4

Human Centered Design and Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, U.S.A.

Keywords: Human-computer Interface, Mobile Learning, Informal Learning, Interest-centered Design.

Abstract: In this study, we investigate whether and how a mobile application called NatureCollections supports chil-

dren’s triggered situational interest in nature. Developed from an interest-centered design framework,

NatureCollections allows children to build and curate their own customized photo collections of nature. We

conducted a comparison study at an urban community garden with 57 sixth graders across 4 science class-

rooms. Students in two classrooms (n = 15 and 16) used the NatureCollections app, and students in another

two classrooms (n = 13 and 13) used a basic Camera app. We found that NatureCollections succeeded in

focusing students’ attention–an important aspect of interest development– through sensory engagement with

the natural characteristics in their surroundings. Students who used NatureCollections moved slower in space

while scanning their surroundings for specific elements (e.g., flowers, birds) to photograph. In contrast, stu-

dents who used the basic Camera app were more drawn to aesthetic aspects (e.g., color, shape) and tended to

explore their surroundings through the device screen. NatureCollections supported other dimensions of inter-

est development, including personal relevance, social interactions, and positive experiences for continued

engagement. Our findings further showed that the NatureCollections app facilitated students’ scientific dis-

course with their peers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Personal interest plays a vital role in learning across

domains (Ainley, 2006; Azevedo, 2013; Hidi & Ren-

ninger, 2006; Krapp, 2002, 2003). When students

form a personal connection to a topic, they are more

likely to feel intrinsically motivated to learn about it,

retain what they have learned, and enjoy the learning

process itself (Ainley, 2006; Hidi & Renninger, 2006;

Krapp, 2002). Prior work investigating nature-related

science learning is consistent with the broader re-

search related to interest-driven learning. When

children have a personal interest in nature, their learn-

ing about nature-related topics increases (Klemmer et

al., 2005; Louv, 2008; O’Brien & Murray, 2007).

To develop interest in nature, one must have pos-

itive experiences outdoors (Azevedo, 2013; Braun &

Dierkes, 2017; Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Krapp, 2002,

2003). Unfortunately, children today are spending

less and less time in contact with nature (Bassett et

al., 2015; Holt et al., 2015; Kimbro et al., 2011; Lohr

& Pearson-Mims, 2004). Although increased screen

time is often blamed for decreasing children’s time

spent outside (Gray et al., 2015; Kimbro et al., 2011;

Louv, 2008), prior work has demonstrated that mobile

technologies can actually support children’s positive,

fun experiences outdoors and can be effective in con-

necting children to nature (Crawford et al., 2017;

Ruiz-Ariza et al., 2018). For instance, recent research

has shown that mobile-enabled activities such as

games (e.g., Pokémon GO) can engage children and

their parents in enjoyable activities, help motivate

them to go outside, and even increase their overall

time spent outdoors (Sobel et al., 2017).

We know less about leveraging mobile technolo-

gies for interest-driven learning about nature. Prior

work has focused on using mobile technologies to en-

gage children in science learning and guided

exploration (Chipman et al., 2006; Kamarainen et al.,

2013; King et al., 2014; Kuhn et al., 2011; Y. Rogers

Kawas, S., Sherry-Wagner, J., Kuhn, N., Chase, S., Bentley, B., Lawler, J. and Davis, K.

NatureCollections: Can a Mobile Application Trigger Children’s Interest in Nature?.

DOI: 10.5220/0009421105790592

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 1, pages 579-592

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

579

Figure 1: a. Student taking a close-up shot of a flower b. One student pointing nature element to her peers a c. Students

walking and scanning their surroundings.

et al., 2004; Yvonne Rogers et al., 2005; Schellinger

et al., 2017; Zimmerman et al., 2016). This research

shows how leveraging affordances such as location

awareness makes it possible to push contextually rel-

evant content to users, thus enriching their learning

experience (Kamarainen et al., 2013; Y. Rogers et al.,

2004; Zimmerman et al., 2016). However, this re-

search has not typically positioned interest

development as a major and explicit consideration in

designing mobile technologies for nature-based sci-

ence learning. At the same time, researchers have

uncovered insights that are relevant to the design of

interest-driven learning experiences with mobile

technologies more broadly (i.e., not specific to na-

ture), which inform the current work. For instance,

prior work shows how introducing overly structured

activities limits a learner’s autonomy. In addition, it

can be difficult to achieve balance between guided ac-

tivities and open-ended exploration—a key

component of interest-driven learning (Azevedo,

2013; Hidi & Renninger, 2006)—when designing

mobile learning technologies (Kamarainen et al.,

2013; Kuhn et al., 2011; Lo et al., 2012; Zimmerman

et al., 2016).

In their four-phase model of interest development,

Hidi and Reninger describe the evolution of an exter-

nally triggered situational interest into a sustained

personal interest (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). In the

current work, we explore how mobile technologies

can support interest-driven exploration in nature, par-

ticularly, the first phase of interest development: a

triggered situational interest. Although typically

short-lived, a triggered situational interest is central

to the model because it contains characteristics that

pervade it, and because it is the necessary precursor

to all other phases of interest development. The char-

acteristics that underpin all phases of the model

include personally relevant experiences, focused at-

tention accompanied by positive emotional

engagements, social interactions,, and opportunities

for re-engagement (Hidi & Renninger, 2006).

In prior work (Kawas et al., 2019), we presented an

interest-centered design framework to promote

children’s interest in nature. Drawing on Hidi and

Reninger’s model of interest development, we derived

a set of four design principles: (1) personal relevance,

(2) focused attention, (3) social interactions, and (4)

opportunities for continued engagement. Through co-

design sessions with children, we developed design

strategies to enact each of these principles (Table 1).

Using this framework, we designed NatureCollections,

a mobile application that allows children to build and

curate photo collections of nature.

In the current study, we evaluate the interest-cen-

tered design principles and strategies embodied in the

NatureCollections app features and the extent to

which, together, they support children’s interest de-

velopment in nature. Our purpose in this evaluation is

to assess whether the system as a whole supports the

emergent behavior of interest, in this case, a triggered

situational interest in nature. This objective stands in

contrast to research that assesses individual design

features or interaction techniques (Greenberg &

Buxton, 2008; Olson & Kellogg, 2014).

In line with this objective, we adopted a qualita-

tive approach in the current investigation, one that

allowed us to identify and describe the emergent be-

havior of interest as children interacted with the

system as a whole, in a real-world setting (Klasnja et

al., 2011; Olson & Kellogg, 2014). The study took

place at an urban garden with 57 sixth graders across

4 science classrooms at a single school. Students in

two classrooms (n =15 and 16) used the NatureCol-

lections app, and students in another two classrooms

(n = 13 and 13) used a basic Camera app. We included

the comparison group to ensure that any effects that

we observed were not due simply to using a

smartphone to take pictures of nature (Jake-

Schoffman et al., 2017; Nayebi et al., 2012). Beyond

ruling out a novelty effect of using a smartphone to

take pictures, our comparison group was not intended

to evaluate any single feature of the app.

The contribution of this work is empirical evi-

dence showing that NatureCollections succeeded in

triggering children’s situational interest in their natu-

ral surroundings. This evidence supports the

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

580

effectiveness of the interest-centered design frame-

work that we used to design NatureCollections. In

addition to showing how the app’s features supported

specific dimensions of the interest development

model (e.g., focused attention), our analysis also un-

covered emergent themes related to students’

scientific discourse and distinct patterns of movement

through nature while using the app, which comple-

ment the interest development framework.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 A Theoretical Model of Interest

Development

Hidi and Renninger describe four distinct and sequen-

tial phases of interest development that depict how a

sustained, internally driven personal interest emerges

from an initial external stimulus (Hidi & Renninger,

2006). The first phase is a triggered situational inter-

est, which occurs from a stimulus in the environment

that sparks an individual’s in-the-moment, focused at-

tention, either because it is personally relevant,

unexpected, or both. The experience is also typically

accompanied by positive feelings. The second phase

is a maintained situational interest, where both fo-

cused attention and positive feelings are sustained

through meaningful interactions over an extended pe-

riod of time. Both a triggered and a maintained

situational interest require external support to materi-

alize. During the third phase, an emerging individual

interest develops from recurrent engagement with a

particular content that the individual values based on

prior experiences. Some external support is typically

needed during this phase to provide reengagement op-

portunities. The last and fourth phase of the model is

a well-developed individual interest, which stems

from an enduring predisposition towards re-engaging

with a topic overtime. This stage is marked by an in-

dividual’s accumulated knowledge, positive feelings,

and supportive social interactions (Hidi & Renninger,

2006).

All four phases share common characteristics that

underpin interest development: focused attention on

personally relevant content accompanied by positive

emotions, supportive social interactions, and oppor-

tunities for continued engagement. We drew on these

characteristics to form the foundational principles in

the interest-centered design framework (Kawas et al.,

2019). In the current evaluation study, we focus on

the first phase of interest development, a triggered sit-

uational interest, as it contains the core characteristics

that pervade the entire model. It is also a necessary

precursor to all other phases of interest development.

2.2 Insights from Mobile Learning

Technologies Research

In addition to being theoretically guided by the inter-

est development model, our work is informed by prior

empirical research on mobile learning technologies

that aim to support learners’ science inquiry and na-

ture-based explorations. Projects like Ambient Wood

(Y. Rogers et al., 2004), Tree Investigators

(Zimmerman et al., 2015), Zydeco (Kuhn et al.,

2011), GeoTagger (Fails et al., 2014), iBeacons

(Zimmerman et al., 2016) and EcoMOBILE

(Kamarainen et al., 2013) harness location awareness

capabilities and just-in-time prompts to deliver rele-

vant content based on the learner’s location to engage

them with their surroundings. For instance, both Eco-

MOBILE and Tree Investigators leverage augmented

reality to overlay images of biodiversity and back-

ground information to amplify learners’ observations

in their surroundings. Similarly, Zydeco and iBea-

cons push relevant information to the mobile device

to connect learners with their surroundings. All these

projects also allow learners to collect and/or annotate

their observations to guide their science inquiry.

Commercial location-based mobile games have

also engaged children with outdoor exploration using

similar features (Ruiz-Ariza et al., 2018; Sobel et al.,

2017). For example, Pokémon Go uses augmented re-

ality features to overlay co-located game characters

onto the physical surrounding. The game also makes

use of just-in-time, location-based prompts to deliver

relevant content, such as the existence of a nearby raid

battle. Research has shown that such games are highly

engaging for children, support social interaction, and

promote positive feelings (Sobel et al., 2017).

There exists a tension between the engaging qual-

ity of mobile learning and game applications, on the

one hand (Kamarainen et al., 2013; Sobel et al., 2017;

Zimmerman et al., 2015), and their tendency to focus

children’s attention on the device screens rather than

their surroundings, on the other (Ruiz-Ariza et al.,

2018; Sobel et al., 2017). Researchers have docu-

mented parents’ and teachers’ concerns about

children being preoccupied with the mobile devices

during outdoor science inquiry (Ayers et al., 2016;

Cahill et al., 2010; Kamarainen et al., 2013). Simi-

larly, parents have worried about their children’s

safety while playing Pokémon Go due to their absorp-

tion in the game world seen through their screen

rather than the physical world through which they are

moving (Ayers et al., 2016; Ruiz-Ariza et al., 2018;

NatureCollections: Can a Mobile Application Trigger Children’s Interest in Nature?

581

Sobel et al., 2017). In designing NatureCollections,

our goal was to design a system that avoids the prob-

lem of focusing on one’s device for extended periods

of time to the exclusion of experiencing one’s natural

surroundings directly.

3 INTEREST-CENTERED

DESIGN FRAMEWORK

In prior work (Kawas et al., 2019), we presented a de-

sign framework comprising a set of design principles

and strategies to guide the design of mobile technol-

ogies to promote children’s interest development in

nature. Development of the framework was guided by

both theoretical and empirical insights. We identified

four design principles by drawing on the core dimen-

sions of the interest development model (Hidi &

Renninger, 2006): (1) personal relevance, (2) focused

attention, (3) social interactions, and (4) opportunities

for continued engagement.

Next, we conducted co-design sessions with chil-

dren aged 7–12 years to generate design strategies to

implement each of the four design principles (See Ta-

ble 1) (Kawas et al., 2019). Throughout this process,

we took into consideration insights and challenges

identified in prior research on designing mobile

learning technologies.

Table 1: (adapted from prior work): Interest-Centered

design principles and strategies.

Mobile Design

Principles

Design Strategies to Support Personal

Interest Development

1. Engage

Children in

Personally

Relevant

Activities

1.1 Support children’s pre-existing personal

interests through customizable activities

1.2 Provide opportunities to extend activities

by unlocking new content

1.3 Create a personalized user interface

2. Support

Children’s

Focused

Attention on

Their

Surroundings

2.1 Draw attention to specific elements i

n

the child’s physical surroundings

2.2 Encourage self-directed, sensory interac-

tions with natural elements

3. Encourage

Children to

Engage in

Social

Interactions

3.1 Connect users with each other and pro-

vide conversational prompts around topics

of interest

3.2 Create activities that involve two o

r

more users to complete

4. Provide

Opportunities

for Continued

Engagement

4.1 Display children’s accumulated progress

over time

4.2 Promote app engagement across settings

3.1 Nature Go App Feature Design

Guided by our interested-centered design framework,

we designed the features of the NatureCollections app

to promote children’s interest in nature. NatureCol-

lections allows children to photograph things they see

in nature, classify plants and animals in their photo-

graphs, and organize them into themed albums such

as birds, insects, and trees. Here, we briefly describe

key app features, along with their connection to the

four design principles and associated design strate-

gies in parentheses () shown in Table 1. (See (Kawas

et al., 2019) for an expanded discussion.)

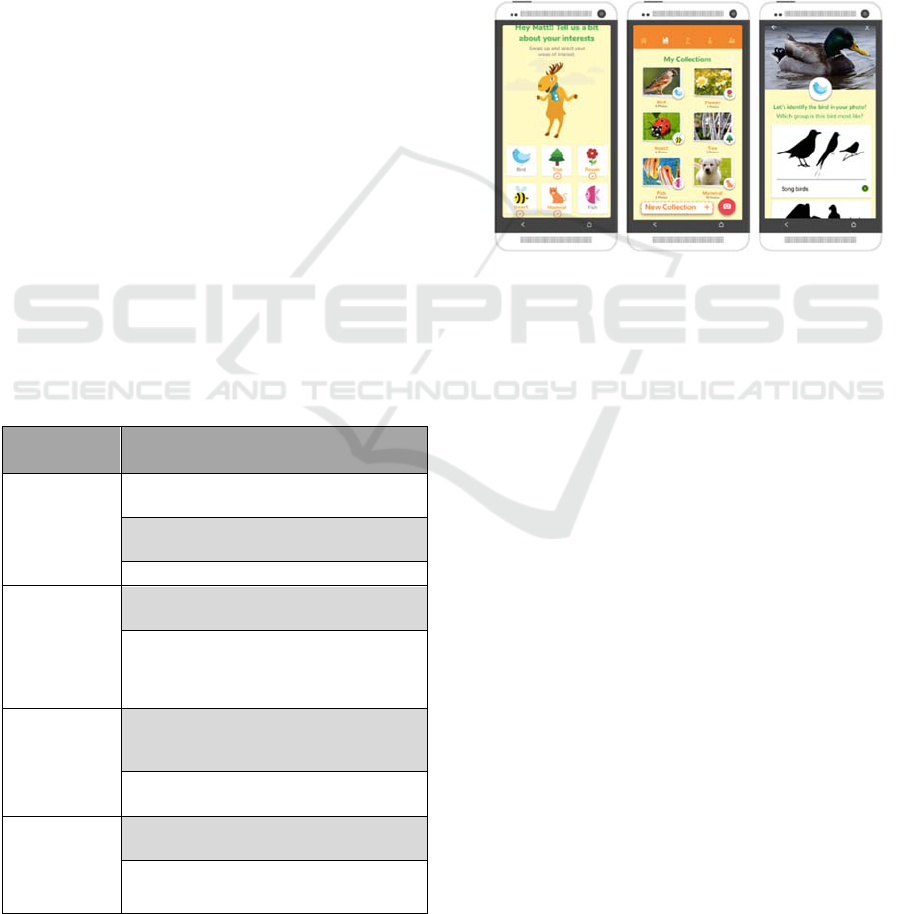

Figure 2: Screens of the NatureCollections app 1: Onboard-

ing “What are your interests?” 2: My Collections. 3: Photo

Classification.

3.1.1 Design Principle 1: Engage Children in

Personally Relevant Activities

During the NatureCollections onboarding process, a

friendly moose character addresses child by their

name, introduces himself as their guide through the

app experience, and prompts them to enter their inter-

ests (design strategies 1.1, 1.2, 1.3) (see Fig 2.1). The

app includes a personalized “Profile Page” where

children can track their accomplishments, including

photos taken, badges earned, and challenges com-

pleted. In addition, children can create and organize

their photographs into customized “My Collections”

that reflect their specific blend of interests (design

strategy 1.1) (Fig 2.2).

3.1.2 Design Principle 2: Support Children’s

Focused Attention on Their

Surroundings

The “Add Details” feature allows children to enter de-

scriptive information about their photo into text fields

using conversational prompts (e.g., “How would you

describe this photo?”). This feature encourages chil-

dren to examine the subject of their photograph

carefully and reflect on specific elements (design

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

582

strategies 2.1, 2.2). The “Photo Classification” fea-

ture similarly encourages children to focus on a

nature element by providing simple classification

schemes for each preset photo collection. These

schemes direct users through a series of stepped

prompts containing visual silhouettes to facilitate

classification (design strategy 2.1) (Fig 2.3).

3.1.3 Design Principle 3: Encourage

Children to Engage in Social

Interactions

Children can see their friends on a “My Friends”

screen, including their photos and badges earned (de-

sign strategy 3.1). New friends can be added through

a unique username. Several “Challenges” are de-

signed to be social. Friends can collaborate on a team

scavenger hunt (earning a team badge), or challenge

each other to match a photo they have already taken

(design strategy 3.2).

3.1.4 Design Principle 4: Provide

Opportunities for Continued

Engagement

NatureCollections features such as “My Profile,”

“My Friends,” and “Challenges” track children’s ac-

cumulated progress over time by displaying their

photo count, badges earned, and friends list (design

strategy 4.1). Challenges span multiple locations to

promote app engagement across settings, providing

opportunities for continued engagement (design strat-

egy 4.2). Progress toward a particular goal is shown

through a “Progress Bar” (design strategy 4.1).

3.2 Basic Camera App

For the current study, we developed a second, basic

Camera app (also titled NatureCollections with the

same app icon) to test whether the behaviors we ob-

served as children used NatureCollections were due

to the app and its collective features, or whether they

were instead attributable to the effect of using a

smartphone to photograph one’s natural surroundings

(Jake-Schoffman et al., 2017; Nayebi et al., 2012).

This app consisted of two main features: (1) a camera

feature with only a single shot (no other photo capture

modes, filters, or video capabilities), and (2) a photo

gallery displaying a grid of all photos taken.

4 METHOD

Our goal in the current study was to understand if and

how the NatureCollections app design succeeds in-

triggering children’s situational interest in nature.

Although the design framework used to develop Na-

tureCollections addresses all four phases of interest

development, we chose to focus this initial evaluation

study on the first phase, a triggered situational inter-

est. A necessary precursor to the other three phases of

interest development, a triggered situational interest

incorporates the core dimensions of interest develop-

ment that pervade the entire model. Moreover, a

triggered situational interest can be witnessed over

the short-term, which was a practical consideration

for this study. We operationalized interest by focus-

ing on behavioral indicators of the four core

dimensions of a triggered situational interest. This

strategy is consistent with other work that uses prox-

imal behavioral indicators as evidence of complex

constructs (such as interest) (Moller et al., 2017).

We conducted an observational in-situ study compar-

ing two groups of students in a community garden.

One group used the NG app and the other used a basic

Camera app (both presented to participants as the Na-

tureCollections app). Prior research has shown that

in-situ studies capture context of use when evaluating

a new mobile technology and often uncover a range

of design and usability issues that lab-based evalua-

tions are likely to miss (Klasnja et al., 2011).

4.1 Participants

Participants were 57 sixth graders aged 11-13 years

(M = 11.5 years) attending a private middle school lo-

cated in an affluent suburb of a city in the Northwest

United States. Students were predominantly

White/Caucasian (73.5%) and lived in households

with a high annual income (see Table 2 for complete

demographic details). In a pre-survey, 100% of par-

ents reported that their children use a tablet or phone

on a daily basis, and 98% of parents reported their

children own their own device. Prior to the study, we

asked students about their general interests, hobbies,

and favorite outdoor and nature-based activities and

found no notable differences between the NG app and

the Camera app groups. Students in both groups were

far more likely to identify organized sports as a favor-

ite activity than a nature-foregrounded activity.

NatureCollections: Can a Mobile Application Trigger Children’s Interest in Nature?

583

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of participants, who

shared their data (n = 49, across all classrooms).

Gender Female (51%), Male (49%)

Age

Mean (SD) = 11.5 (0.54) | Age 11

(n=26), Age 12 (n =22) Age 13 (n =1)

Race

White (73.5%), Asian/Pacific Islande

r

(16.5%), Hispanic (4%), Africa

n

American (2%), Middle Eastern (2%),

Mixed (2%)

Household

Income (US$)

Less than 25K (2%), 25k-49K (2%),

50k-74k (4%), 75K-99K (4%),

100K-125K (14.5%), Over 150

K

(73.5%)

4.2 Procedures

We conducted the study with four different classrooms

over a two-day period during their regular science class

period. Since the study took place over two consecu-

tive days and to account for weather and time of day

effects (e.g., energy levels may vary before and after

breaks), we used controlled random cluster assign-

ments to assign the NatureCollections app and the

Camera app to classrooms on both days. Two class-

rooms used the NG app (15, 16 students in each

classroom, total = 31), and two classrooms used the

basic Camera app (13 in each classroom, total = 26)

(see Table 3). All four classrooms were told they were

using a beta version of the NatureCollections app. Be-

yond introducing the researchers to the students,

classroom teachers did not help the researchers run the

study. They did, however, stay to observe their stu-

dents and direct their questions to a researcher.

After explaining the study purpose, we divided the

students randomly into small groups (4–5 students, 1

researcher per group). We obtained student assent,

gathered parental consent forms, and administered a

pre-activity questionnaire (described above). Re-

searchers then led students in an outdoor icebreaker

activity before introducing them to the photo-taking

activity and handing out the phones with the app.

Table 3: App Class Assignment.

The photo-taking activity took place at a nearby

urban community garden. Students in both groups

were invited to explore their surroundings and take

photos using the app for approximately 25 minutes.

Researchers were careful not to prime children by dis-

cussing details of the research project; rather, we

asked them to help us try and give feedback on the

nature app and reinforced that there were no right or

wrong ways to use the app. In addition to videotaping

the students’ activity using chest-mounted GoPro

cameras, researchers followed small groups of stu-

dents to take observational field notes and ask them

questions about their photo choices and app function-

ality. Following the activity, students returned to the

classroom to participate in a semi-structured focus

group discussion led by the researcher within their

small groups. In this debrief discussion, we asked stu-

dents about what pictures they took and their rationale

for taking them, what they liked and disliked, and if

they had suggestions for additional features.

4.3 Data Analysis

We used the video recordings of the sessions to ex-

amine triggered situational interest “moments” in

detail across the two groups. The video recordings

were central to our analysis; they included 18 total

videos of the outdoor activity ranging from 25 to 29

minutes each. The recordings of the post-activity

small-group discussions were secondary in our anal-

ysis; they included 18 debrief videos lasting

approximately 15 minutes each. We analyzed our

data thematically using both etic and emic codes

(Boyatzis, 1998; Maxwell, 1996). Etic codes repre-

sented behavioral evidence of the core dimensions

associated with a triggered situational interest: (1)

personal relevance, (2) focused attention, (3) social

interactions, and (4) opportunities for continued en-

gagement. Due to the short-term nature of a triggered

situational interest (and of our study), we did not ex-

pect to see robust evidence relating to continued

engagement. Instead, we considered indicators that

students were open to re-engage with the NG app if

given future opportunities. Although we focused cen-

trally on these etic coding categories, we also used a

grounded theory approach to coding (Glaser &

Strauss, 1967) that allowed for emic themes to

emerge directly from the data (Maxwell, 1996).

We used interactional analysis and video research

techniques to analyze the video data (Derry et al.,

2010; Jordan & Henderson, 1995). The 6 researchers

who led the analysis were not involved with the NG

app design process. Researchers individually created

a content log for the GoPro video they captured, and

conducted an initial coding based on the four design

principles contained in the design framework. While

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

584

logging, researchers flagged segments for more in-

tense analysis and other salient emergent themes

based on alignment with the interest development

model (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). After indexing the

video data, the research team collectively viewedeach

video alongside its respective content log, stopping

for group discussion at the identified flagged seg-

ments. Researchers resolved disagreements and came

to consensus on the appropriate coding before moving

to the next segment (Derry et al., 2010; Jordan &

Henderson, 1995). During this process, researchers

highlighted “hotspots” representing triggered situa-

tional interest moments and examples of the emergent

salient themes (Jordan & Henderson, 1995). After the

group viewing, three researchers repeatedly

viewed

the identified hotspots to document the triggered sit-

uational interest moments in detail.

We used the codes from the community garden

activity analysis to code the video data of the post-

activity focus group discussions. Two researchers

viewed one video from each app assignment and

coded it together to establish agreement. One re-

searcher then coded the remaining videos and

transcribed students’ responses for each small group.

We chose not to analyze the content of children’s

photos, as photo content itself does not offer deep in-

sight into students’ attention, intent, or experience.

Instead, we focused on qualitative observational and

interview methods to gauge children’s interactions

with the app and their interest in nature.

5 RESULTS

We present results from our analysis exploring the re-

lationships between our etically derived interest

development themes: Personal Relevance, Focused

Attention, Social Interactions, and Opportunities for

Continued Engagement and the students’ interactions

with the assigned app and their natural surroundings.

In addition, we discuss two related themes that

emerged emically: Science Discourse and Mobility.

We include vignettes from the video data (outdoor ac-

tivity and focus group debriefs) to illustrate how

NatureCollections features supported specific dimen-

sions of a triggered situational interest, followed by

our observations of the Camera app group.

5.1 Personal Relevance

We observed several instances where the students

verbally indicated a connection between the NG app

and their existing interests. NG features allowed stu-

dents to choose the nature photos they wanted to

collect, as one student expressed aloud while select-

ing her interests on the onboarding screen, “Oh my

god, I forgot about rocks, rocks are like my favorite

things. I had so many rock pets when I was younger”.

We also noticed that the NG app features, such as

“My Collections,” prompted students to notice and

take interest in unexpected and unsought elements in

their surroundings. One student described to a re-

searcher the pictures he was taking, “I’m just finding

insects for my collection, that’s all.” He then said, “I

lost it!” and pointed his phone up in the air and said,

“Oh, there! I see it” while another student crouched

down next to him and lifted his phone up higher and

exclaimed, “They’re too small” (referring to the in-

sects). The first student pointed to the insects area

and said, “Yeah most of them, they’re right there.”

During the small group debriefs, several students

mentioned that their choice of photos was driven, in

part, by things they were already interested in, such

as rocks and flowers. For example, one of the students

explained, “I took photos of flowers because I like

flowers,” and she continued saying, “I got excited

when I found flowers to take pictures of.” Another

student said “I took a photo of Winston” When the re-

searcher asked, “Who is Winston?” she replied, “It’s

my pet rock, I named it” showing the researcher and

her peers the photo of the rock.

Students across the small groups noted that they

liked the Collections feature. They observed that it

helped them to organize their photos based on their

interests, as this student explained, “I took pictures

because it was a collection of photos, so I was not just

taking random photos…and I like small plants, so I

took photos of them.” Students indicated they liked

being able to create their own custom collections.

5.2 Focused Attention

5.2.1 Direction of Attention

Students in the NG app sessions appeared considera-

bly more focused on their surroundings than their

device. The teacher in attendance remarked to a re-

searcher, “For a person who experiences them daily,

this is what ‘focused’ is.” When students did look at

their device, their gaze alternated between the app and

the nature element. This typically happened when

they were photographing, entering captions, or com-

pleting a classification for a nature element.

We observed that specific app features prompted

students to focus on their surroundings. For instance,

the “Challenges” encouraged students to search for

specific nature elements, which led them to focus

much of their gaze on scanning the community

NatureCollections: Can a Mobile Application Trigger Children’s Interest in Nature?

585

garden as opposed to observing objects through their

device screen. One student mumbled while looking

closely at garden plots, “I need two more photos of

flowers.”

5.2.2 Sense-making

When students classified a photo using the “Classifica-

tion” feature, the prompts encouraged them to focus on

specific characteristics of a nature element. In one in-

stance, three students looked at the ground, having

finished photographing a pale spaghetti squash and

now trying to classify it. Moving their gaze between

the ground and their app, these students discussed

which details and classification to assign to the photo.

One said, “That’s an egg,” another responded, “I know

it’s an egg,” and a third student said, “No it isn’t, it’s

a plant, it’s a squash, can’t you see the stem?” The

second replied, “Oh yeah, it is,” and the third contin-

ued, “That has to be like an ostrich egg.”

5.2.3 Tactile Interactions

Students also interacted tactilely with particular

elements while photographing them. We observed

students, while adding details or classifying their pho-

tos, move closer to plants to touch leaves or kneel to

feel the grass. For instance, one student, when trying

to determine whether a plant was cabbage, moved

closer to touch its large leaves. Several other students

knelt to get closer to the ground to touch and take pho-

tos of an insect they had spotted. (See Fig 2 for the

classification screen).

5.3 Social Interaction

5.3.1 Peer Engagement

Social interaction started immediately upon engaging

with the NG app, with students helping peers discover

new app features. Throughout the activity, students

engaged in robust social interactions that involved not

only showing each other their photos and earned

badges, but also copying each other by photographing

nature elements that their peers showed interest in or

had photographed. They also provided suggestions to

each other on which nature elements would be inter-

esting to photograph, and helped each other find

photos to complete challenges. In one instance, a stu-

dent ran up to her friend, who was crouched down

taking a photo of a plant, and excitedly told her, “I

found a purple flower!” Her friend asked where, and

she gestured for her friend to follow her. They both

walked quickly to a garden bed where she pointed to

a flower close to the ground. Her friend immediately

crouched down to take a close-up photo of the flower

and then she checked her friend’s progress with the

flower challenge.

NG app students were often exploring together

and engaged in collaborative discussions about what

they found and how to name or categorize their pho-

tos as with the example of the “ostrich egg, spaghetti

squash” above. In another instance, a student took a

photo of the same shrub as his friend and asked, “Oh,

what should I put in here? [referring to the Detail

screen],” to which his friend responded “shrub, I

guess.” The first student exclaimed, “Oh snap! Yeah,

I earned a new badge!” and his friend replied, “It

looks like I earned a badge, too.”

We also observed more competitive interactions

between students, such as comparing their total number

of photos, completed challenges, and earned badges.

One girl remarked, “You made it a competition,” while

another responded, “If it is a competition that means I

won [referring to their badge counts].”Students

seemed to find competing to earn badges motivating to

find new things to photograph in nature.

5.3.2 Playful Interactions

Students seemed to be having fun with each other

when they were using the NG app, showing excite-

ment when they were sharing what they noticed. In

one instance, a student excitedly called to his friends,

“Oh come here! Come here! I wonder what this is!”

kneeling to get close to a plant, “this is so cool!” His

friend responded, “It’s a spiky broccoli” following

his friend to take a photo of it as well. Students had

fun exchanging ideas about what captions to add to

their photos. While photographing a stone figure, for

instance, one student referred to it as a “fat snail” and

both giggled. The other said, “Put it in the Stones and

Amphibians collections” and continued to laugh. Stu-

dents also celebrated with each other when they

earned a badge; for example, we observed three stu-

dents high fiving each other when they earned a badge

for taking a photo of a rock.

5.4 Opportunities for Continued

Engagement

Due to the short duration of the study, we did not an-

ticipate that our analysis would uncover substantial

evidence relating to opportunities for continued en-

gagement with the app. Nevertheless, we did identify

several indicators that we believe increase the chances

of students’ re-engagement with the NG app (Fig. 3,

bottom right). For example, students’ evident engage-

ment in the activity and their positive emotions—both

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

586

described above—suggest they would be inclined to

use the app again in the future.

Students expressed verbally in the post-activity

discussion that they would use the app if they had it

on their own devices. Several students said they were

motivated by the challenges and desired to earn

badges. One student in the NG app session explained,

“Getting [the] Aspiring Botanist badge makes me

want to earn more badges.” He continued “I’ll prob-

ably do the challenges…I think this would get me

outside more...like Facebook draws you in.” This

positive desire for continued engagement frequently

manifested in the post-activity discussions, as stu-

dents talked about the many ways they were

interested in continuing to use the app beyond the ses-

sion to document nature on hikes, while camping, and

even in their own home gardens.

5.5 Science Discourse

Certain features of the NG app appeared to facilitate

discussions between students about the natural ele-

ments in the surrounding area of the activity. Students

engaged in science discourse as they collaborated to

categorize their photos in collections and when

choosing the classification options (Fig. 3, top right).

For instance, one student asked his friend, “Are

humans mammals?” while trying to classify the photo

he took of his friend. Another student pointed out to

his friend, “Did you see the hummingbird?” then

added as he was trying to classify the photo he took,

“Is it a songbird?”

Several other students asked their science teacher

repeatedly about the plants they did not recognize. At

one point, two students were asking the teacher ques-

tions about plants when a student, crouching on the

ground, exclaimed to get his teacher’s attention,

“Wooo! Is it a broccoli?” At the same time, another

student moved close to touch a plant and asked the

teacher, “Is it a cabbage?” The teacher pointed to the

plants in sequence and explained, “We got kale,

chard, and this, I don't know what this is, but I have

seen it at the grocery store.” Then another student

said “Is it rainbow choy?”

Students also discussed the influence of seasons

and geographical location on the nature elements they

observed, noticing that some plants grow in certain

seasons, as illustrated by the earlier example of one

student who wondered how she could find a flower in

winter. Students also discussed animal behavior. As

one student searched for an animal to complete the

mammals challenge, another student said to him,

“There's no animals out in the rain."

5.6 Mobility

Across all of the NG app sessions, we observed stu-

dents moving at a slower speed and scanning their

surroundings more carefully as they searched for nat-

ural elements to photograph in the community garden

(Fig. 3, top right). We hypothesize that this intention-

ality of movement supported their focused attention

on nature. Students were also more likely to kneel

down and position themselves closer to the natural el-

ements they saw while using the NG app.

In addition, we noticed that students in the NG

sessions showed distinct patterns of movement in

small groups as they explored their natural surround-

ings together. Compared to the Camera app groups,

NG app students were more likely to move in clusters

and stay closer to friends, whether to compete or col-

laborate on completing challenges and identifying the

elements in the community garden (Fig. 3, bottom

left). We suggest that this spatial mobility was also

critical to how students influenced each other’s photo

choices, as they were more likely to point out and dis-

cuss natural elements in their surroundings when they

moved together.

5.7 Basic Camera App Group

Compared to students using the NG app, students in

the Camera app group displayed notably different pat-

terns of behavior in each of our four etic and two emic

themes, as described below.

5.7.1 Personal Relevance

Overall, we documented less evidence of students

forming a personal connection to the activity when

using the Camera app. When we did see a personal

connection, it tended to be around photography rather

than nature. In one of the sessions, for example, a stu-

dent uttered, "I love photography," and a fellow

student responded, "I know, same" while they were

both capturing photos using the Camera app. This

finding is not surprising when one considers that the

two main features of the Camera app were the photo

capture and photo gallery; nothing in the app

prompted students to connect personally with nature

beyond the name of the app (NatureCollections) and

the researcher’s initial prompt to take pictures of na-

ture during the activity.

5.7.2 Focused Attention

In the Camera app sessions, students’ interactions

with their surroundings appeared to be mediated pri-

marily through the device. The majority of the

NatureCollections: Can a Mobile Application Trigger Children’s Interest in Nature?

587

students looked through their phone screens to frame

potential elements they considered photographing.

For instance, one student mumbled while focusing the

camera on a specific shrub, “Let's take some more

pictures of this.” Throughout the interaction, his gaze

remained on the screen; he never looked directly at

the bush. Students’ attention seemed to be focused on

the aesthetic aspects of nature elements when decid-

ing what to photograph. When asked in the post-

activity focus group sessions, students explained that

vivid colors, light patterns, and unique shapes were

things they were interested in capturing. One student

explained, “Anything that's brightly colored or seems

unique," and another replied, “Really colorful stuff,

colorful plants, colorful step stones, or yeah, like

plants.” Students also mentioned the composition of

elements, experimenting with different camera angles

when framing photos. For instance, one student

showed a researcher a photo he had taken of a small

plant, noting, “Look, I sorta make it look like a tree…

I took it from underneath.” We did not observe stu-

dents articulating observations of specific non-

aesthetic characteristics (e.g., identifying the type of

plant), as we did in the NG groups. We also did not

observe students in this group move closer to or touch

the different nature elements they photographed.

5.7.3 Social Interactions

Students in the Camera app groups displayed notably

different patterns of peer interaction, engaging in fewer

app-related, nature-focused interactions with their

peers. The interactions were more likely to be mediated

through the phone screen as students took photos of

one another and played offline games. For instance, we

observed a group of students walking around the com-

munity garden together. They slowed down together in

three different areas and spent no more than 5 seconds

in each area. They had little interaction with each other

while taking photos, which were often of different

things. There was little discussion among them about

their photos. The playful interactions we observed in

this group typically consisted of posing for or taking

photos of and with their peers rather than nature. Dur-

ing the post-activity debrief, students were excited to

share with researchers the photos they had taken of

themselves and their peers.

5.7.4 Opportunities for Continued

Engagement

Overall during the Camera app session, we did not

observe the same level of excitement among students

using the app. On the contrary, many students ap-

peared to be disengaged from the photo-taking

activity. Nearly two-thirds of the students in one ses-

sion turned to an offline game on the device’s default

browser (the phones had no data plans and were not

connected to WiFi) out of self-reported boredom.

5.7.5 Science Discourse

Similar to the NG app groups, we did observe some

students discussing what counts as nature. However,

these conversations appeared to be prompted primar-

ily by the title of the app (NatureCollections). For

instance, one student yelled when his friend tried to

take a picture of a garden trellis grid, “That's not na-

ture enough!” In fact, one group of students thought

that the Camera app could only take photos of nature.

They quickly abandoned this idea (and their focus on

their natural surroundings) when they tried to take a

selfie and the photo appeared in their gallery.

5.7.6 Mobility

During the Camera app sessions, students appeared to

be more aimless and wandering in their movements.

We observed students move faster through different

parts of the environment, snapping pictures in a seem-

ingly haphazard way. In these sessions, students

displayed a tendency to search alone for things to

photograph, and they gave photos only momentary

focus before moving on. This led to students being

scattered and spread out in different directions during

the activity.

6 DISCUSSION

In the current work, we investigated whether and how

the NatureCollections app as a whole succeeded in

triggering children’s situational interest in nature. Our

analysis of sixth-grade students’ interactions with Na-

tureCollections showed that the app’s features

collectively supported the four behavioral elements of

personal interest that we investigated: personal rele-

vance, focused attention, social interaction, and

positive experiences for continued. In addition, we

documented two emergent themes in our analysis:

children’s distinct patterns of mobility around the

community garden and their engagement in science

discourse with peers. Both of these behaviors related

to and supported the four dimensions of interest de-

velopment. Our findings point to the effectiveness of

the interest-centered design framework used to design

NatureCollections (Kawas et al., 2019). We conclude

that, collectively, the design strategies embodied in

the NatureCollections app hold promise for solving

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

588

the problem of children’s decreased time spent and

interest in nature (Clements, 2004; Holt et al., 2015;

Lohr & Pearson-Mims, 2004), with implications for

supporting interest-driven learning about nature

(Klemmer et al., 2005; Louv, 2008).

Our video analysis revealed how the design fea-

tures of NatureCollections supported specific

dimensions of interest development model (Hidi &

Renninger, 2006). Moreover, our analysis of the stu-

dents in the comparison Camera app group showed

that the absence of these design features produced no-

tably different behaviors in children. For instance, the

NG app succeeded in supporting children’s focused

attention on the natural elements in their surroundings

through features such as “Challenges,” which prompt

children to search for specific elements in nature, and

“Photo Classification,” which requires children to fo-

cus on specific characteristics of an element in order

to identify it. Although children in the basic Camera

app group also focused their attention on natural ele-

ments in their environment, the Camera app’s limited

palette of features, both of which emphasized taking

pictures rather than exploring nature, resulted in fo-

cusing children’s attention on the act of setting up and

taking aesthetically pleasing photographs rather than

on the characteristics of the nature element they were

photographing. In this way, the Camera app func-

tioned much like prior outdoor mobile learning

technologies, which have consistently faced chal-

lenges associated with focusing children’s attention

on their device at the expense of engaging with their

surroundings (Cahill et al., 2010; Kamarainen et al.,

2013; Sobel et al., 2017).

Similarly, the “Onboarding” and “My Profile”

features, among others, supported children’s self-di-

rected, personalized exploration of nature. Lacking

such features, children in the Camera app group

tended to connect personally to the act of photog-

raphy, if they formed a personal connection at all.

Self-guided, personalized exploration also had the ef-

fect of drawing children’s attention to surprising

elements in their surroundings, which they experi-

enced as enjoyable, particularly when they shared

them with their friends. Children using the Na-

tureCollections app displayed excitement engaging

with their environment and with their peers, and they

conveyed their interest in continued engagement with

the app beyond the study session. In contrast, children

using the basic Camera app quickly lost interest in

both the app and the activity. These differences sug-

gest that it was the NatureCollections app and its

unique set of design features, rather than the mere

novelty effect of using a smartphone to take photo-

graphs of nature, that succeeded in triggering

children’s situational interest in nature.

Although our analysis focused on teasing out indi-

vidual design features and tying them to specific

behavioral indicators of interest development, we un-

derscore that it is the system as a whole that supported

the emergent behavior of a triggered situational interest

in nature. To help make this point, consider the find-

ings related to social interaction. Children in both the

NatureCollections sessions and the Camera app ses-

sions engaged in social interactions with their peers

during the activity. However, features such as “My

Friends,” “Challenges,” and “Badges” shaped chil-

dren’s social interactions in distinct ways compared to

the basic Camera app group. Importantly, the distinct

quality of social interactions we observed in the Na-

tureCollections sessions appeared to support other key

dimensions of Hidi and Reninger’s interest develop-

ment model. For example, children helped each other

discover the app’s various features, such as how to use

the “Photo Classification” and “Challenges” features to

tailor a personally relevant and meaningful app expe-

rience that involved focused attention on nature. They

further supported each other’s focused attention by ex-

ploring their environment together, giving each other

suggestions about what to photograph, and helping

each other to classify the nature elements in their pic-

tures. In addition, their playful interactions around

collecting, classifying, and earning badges contributed

to their engagement in and enjoyment of the activity,

which we interpret as increasing their likelihood to re-

engage in the activity in the future (Azevedo, 2013;

Hidi & Renninger, 2006). By contrast, the social inter-

actions we documented among children in the Camera

app sessions were centered to a greater degree on tak-

ing photos of each other rather than exploring and

taking photos of their natural surroundings. These so-

cial interactions were neither nature-oriented nor were

they supportive of the other dimensions of interest de-

velopment. This example highlights the novel

contribution of this work: we have provided empirical

evidence that embodying the design strategies of the

interest-centered design framework in NatureCollec-

tions can support children’s interest development in

nature.

7 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Our study included students from an affluent school,

limiting the generalizability of our results. Moreover,

NatureCollections: Can a Mobile Application Trigger Children’s Interest in Nature?

589

although the participants’ racial diversity was reflec-

tive of the city in which the study was conducted, it is

not representative of the broader US population. As

prior research has shown, attitudes with nature are in-

fluenced by demographic variables (Lohr & Pearson-

Mims, 2004; Louv, 2008). Therefore, it would be use-

ful to evaluate NatureCollections with students from

diverse backgrounds to determine whether they re-

spond differently to the app. Further, the current study

was conducted as part of a school-based science class

and took place in a natural setting (i.e. community

garden). Students’ behaviors with the app and the out-

door activity might be different in other contexts (e.g.

urban settings) when they are not surrounded by na-

ture and when they are not being observed by their

teacher.

We also had a camera crew with videography

equipment, which might have altered students’ be-

haviors. However, because these limitations apply to

both groups across sessions, we are optimistic that

distinctions in behavior between app groups remain

meaningful.

In future work, we will deploy the Na-

tureCollections app in the field over a longer period

of time to evaluate whether it succeeds in triggering

children’s interest in nature over the long-term.

8 CONCLUSIONS

We presented a comparative, in-situ study examining

the extent to which the features of the NatureCollec-

tions app, developed from an interest-centered design

framework, supported children’s triggered situational

interest in nature. We found that, in the short-term,

NatureCollections succeeded in triggering situational

interest by connecting to students’ personal interests,

focusing their attention on the natural elements in

their surroundings, encouraging social interactions

among their peers, and promoting positive feelings–

evidence we interpret as a likelihood to re-engage

with the app. Compared to the basic Camera app

group, students using the NatureCollections app also

displayed different patterns of movement and science

discourse with their peers that further supported their

engagement with nature. This study contributes em-

pirical evidence that the interest-centered design

framework can be used successfully to develop mo-

bile applications that support children’s interest-

centered engagement in nature.

REFERENCES

Ainley, M. (2006). Connecting with Learning: Motivation,

Affect and Cognition in Interest Processes. Educational

Psychology Review, 18(4), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.

1007/s10648-006-9033-0

Ayers, J. W., Leas, E. C., Dredze, M., Allem, J.-P.,

Grabowski, J. G., & Hill, L. (2016). Pokémon GO—A

New Distraction for Drivers and Pedestrians. JAMA In-

ternal Medicine, 176– 12. https://doi.org/10.1001/

jamainternmed.2016.6274

Azevedo, F. S. (2013). The Tailored Practice of Hobbies

and Its Implication for the Design of Interest-Driven

Learning Environments. Journal of the Learning

Sciences, 22(3), 462–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/

10508406.2012.730082

Bassett, D. R., John, D., Conger, S. A., Fitzhugh, E. C., &

Coe, D. P. (2015). Trends in Physical Activity and

Sedentary Behaviors of United States Youth. Journal of

Physical Activity and Health. https://doi.org/10.1123/

jpah.2014-0050

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative

information: Thematic analysis and code development.

SAGE.

Braun, T., & Dierkes, P. (2017). Connecting students to

nature – how intensity of nature experience and student

age influence the success of outdoor education

programs. Environmental Education Research, 23(7),

937–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.

1214866

Cahill, C., Kuhn, A., Schmoll, S., Pompe, A., & Quintana,

C. (2010). Zydeco: Using Mobile and Web Technolo-

gies to Support Seamless Inquiry Between Museum and

School Contexts. Proceedings of the 9th International

Conference on Interaction Design and Children,

174–177. https://doi.org/10.1145/1810543.1810564

Chipman, G., Druin, A., Beer, D., Fails, J. A., Guha, M. L.,

& Simms, S. (2006). A Case Study of Tangible Flags:

A Collaborative Technology to Enhance Field Trips.

Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Interaction De-

sign and Children, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1145/

1139073.1139081

Clements, R. (2004). An Investigation of the Status of Out-

door Play. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood,

5(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2004.5.1.10

Crawford, M. R., Holder, M. D., & O’Connor, B. P. (2017).

Using Mobile Technology to Engage Children with Na-

ture. Environment and Behavior, 49(9), 959–984.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916516673870

Derry, S. J., Pea, R. D., Barron, B., Engle, R. A., Erickson,

F., Goldman, R., Hall, R., Koschmann, T., Lemke, J. L.,

Sherin, M. G., & Sherin, B. L. (2010). Conducting

Video Research in the Learning Sciences: Guidance on

Selection, Analysis, Technology, and Ethics. Journal of

the Learning Sciences,19. https://doi.org/10.1080/

10508400903452884

Fails, J. A., Herbert, K. G., Hill, E., Loeschorn, C.,

Kordecki, S., Dymko, D., DeStefano, A., & Christian,

Z. (2014). GeoTagger: A Collaborative and Participa-

tory Environmental Inquiry System. Proceedings of the

Companion Publication of the 17th ACM Conference

on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social

Computing, 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556420.

2556481

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

590

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of

grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research.

Aldine Publishing.

Gray, C., Gibbons, R., Larouche, R., Sandseter, E.,

Bienenstock, A., Brussoni, M., Chabot, G., Herrington,

S., Janssen, I., Pickett, W., Power, M., Stanger, N.,

Sampson, M., Tremblay, M., Gray, C., Gibbons, R.,

Larouche, R., Sandseter, E. B. H., Bienenstock, A., …

Tremblay, M. S. (2015). What Is the Relationship be-

tween Outdoor Time and Physical Activity, Sedentary

Behaviour, and Physical Fitness in Children? A

Systematic Review. International Journal of Environ-

mental Research and Public Health, 12(6).

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606455

Greenberg, S., & Buxton, B. (2008). Usability Evaluation

Considered Harmful (Some of the Time). Proceedings

of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1145/

1357054.1357074

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The Four-Phase Model

of Interest Development. Educational Psychologist,

41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/

s15326985ep4102_4

Holt, N. L., Lee, H., Millar, C. A., & Spence, J. C. (2015).

‘Eyes on where children play’: A retrospective study of

active free play. Children’s Geographies, 13(1), 73–88.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.828449

Jake-Schoffman, D. E., Silfee, V. J., Waring, M. E.,

Boudreaux, E. D., Sadasivam, R. S., Mullen, S. P.,

Carey, J. L., Hayes, R. B., Ding, E. Y., Bennett, G. G.,

& Pagoto, S. L. (2017). Methods for Evaluating the

Content, Usability, and Efficacy of Commercial Mobile

Health Apps. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 5(12).

https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.8758

Jordan, B., & Henderson, A. (1995). Interaction Analysis:

Foundations and Practice. The Journal of the Learning

Sciences, 4(1), 39–103.

Kamarainen, A. M., Metcalf, S., Grotzer, T., Browne, A.,

Mazzuca, D., Tutwiler, M. S., & Dede, C. (2013).

EcoMOBILE: Integrating augmented reality and

probeware with environmental education field trips.

Computers & Education, 68, 545–556.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.02.018

Kawas, S., Chase, S., Yip, J., Lawler, J., & Katie, D. (2019).

Sparking Interest: A Design Framework for Mobile

Technologies to Promote Children’s Interest in Nature.

International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction.

Kimbro, R. T., Brooks-Gunn, J., & McLanahan, S. (2011).

Young children in urban areas: Links among neighbor-

hood characteristics, weight status, outdoor play, and

television watching. Social Science & Medicine, 72(5),

668–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.

015

King, C., Dordel, J., Krzic, M., & Simard, S. W. (2014).

Integrating a Mobile-Based Gaming Application into a

Postsecondary Forest Ecology Course. Natural

Sciences Education. https://doi.org/10.4195/nse2014.

02.0004

Klasnja, P., Consolvo, S., & Pratt, W. (2011). How to

Evaluate Technologies for Health Behavior Change in

HCI Research. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 3063–3072.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979396

Klemmer, C. D., Waliczek, T. M., & Zajicek, J. M. (2005).

Growing Minds: The Effect of a School Gardening Pro-

gram on the Science Achievement of Elementary

Students. HortTechnology, 15(3), 448–452.

Krapp, A. (2002). Structural and dynamic aspects of inter-

est development: Theoretical considerations from an

ontogenetic perspective. Learning and Instruction,

12(4), 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-

4752(01)00011-1

Krapp, A. (2003). Interest and human development: An ed-

ucational psychological perspective. In Development

and motivation (pp. 57–84). British Psychological So-

ciety.

Kuhn, A., Cahill, C., Quintana, C., & Schmoll, S. (2011).

Using Tags to Encourage Reflection and Annotation on

Data During Nomadic Inquiry. Proceedings of the

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, 667–670. https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.

1979038

Lo, W. T., Delen, I., Cahill, C., Kuhn, A., Schmoll, S., &

Quintana, C. (2012). A New Type of Learning

Experience in Nomadic Inquiry: Use of Zydeco in the

Science Center. 2012 IEEE Seventh International

Conference on Wireless, Mobile and Ubiquitous Tech-

nology in Education (WMUTE). https://doi.org/10.

1109/WMUTE.2012.16

Lohr, V. I., & Pearson-Mims, C. H. (2004). The Relative

Influence of Childhood Activities and Demographics

On Adult Appreciation For The Role Of Trees In

Human Well-Being. Acta Horticulturae, 253–259.

https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2004.639.33

Louv, R. (2008). Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our

Children from Nature-deficit Disorder. Algonquin

Books.

Maxwell, J. A. (1996). Qualitative research design: An

interactive approach. Sage Publications.

Moller, A. C., Merchant, G., Conroy, D. E., West, R.,

Hekler, E. B., Kugler, K. C., & Michie, S. (2017).

Applying and advancing behavior change theories and

techniques in the context of a digital health revolution:

Proposals for more effectively realizing untapped

potential. Journal of Behavioral

Medicine.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9818-7

Nayebi, F., Desharnais, J., & Abran, A. (2012). The state of

the art of mobile application usability evaluation. 2012

25th IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and

Computer Engineering (CCECE), 1–4.

https://doi.org/10.1109/CCECE.2012.6334930

O’Brien, L., & Murray, R. (2007). Forest School and its

impacts on young children: Case studies in Britain.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 6(4), 249–265.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2007.03.006

Olson, J. S., & Kellogg, W. (2014). Ways of knowing in

HCI. Springer.

Rogers, Y., Price, S., Fitzpatrick, G., Fleck, R., Harris, E.,

Smith, H., Randell, C., Muller, H., O’Malley, C.,

NatureCollections: Can a Mobile Application Trigger Children’s Interest in Nature?

591

Stanton, D., Thompson, M., & Weal, M. (2004). Ambi-

ent Wood: Designing New Forms of Digital

Augmentation for Learning Outdoors. Proceedings of

the 2004 Conference on Interaction Design and

Children: Building a Community, 3–10.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1017833.1017834

Rogers, Yvonne, Price, S., Randell, C., Fraser, D. S., Weal,

M., & Fitzpatrick, G. (2005). Ubi-learning Integrates

Indoor and Outdoor Experiences. Commun. ACM,

48(1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1145/1039539.

1039570

Ruiz-Ariza, A., Casuso, R. A., Suarez-Manzano, S., &

Martínez-López, E. J. (2018). Effect of augmented

reality game Pokémon GO on cognitive performance

and emotional intelligence in adolescent young.

Computers & Education, 116. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.compedu.2017.09.002

Schellinger, J., Mendenhall, A., Alemanne, N. D.,

Southerland, S. A., Sampson, V., Douglas, I., Kazmer,

M. M., & Marty, P. F. (2017). “Doing Science” in

Elementary School: Using Digital Technology to Foster

the Development of Elementary Students’

Understandings of Scientific Inquiry. Eurasia Journal

of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education.

https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00955a

Sobel, K., Bhattacharya, A., Hiniker, A., Lee, J. H., Kientz,

J. A., & Yip, J. C. (2017). It wasn’t really about the

Pokémon: Parents’ Perspectives on a Location-Based

Mobile Game. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems -

CHI ’17, 1483–1496. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.

3025761

Zimmerman, H. T., Land, S. M., Maggiore, C., Ashley, R.

W., & Millet, C. (2016). Designing Outdoor Learning

Spaces With iBeacons: Combining Place-Based

Learning With the Internet of Learning Things.

Zimmerman, H. T., Land, S. M., McClain, L. R., Mohney,

M. R., Choi, G. W., & Salman, F. H. (2015). Tree

Investigators: Supporting families’ scientific talk in an

arboretum with mobile computers. International

Journal of Science Education, Part B, 5(1), 44–67.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2013.832437

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

592