PROGDASH: Lessons Learned from a Learning Dashboard In-the-wild

Mohamed Ez-zaouia

1,3,4

, Aur

´

elien Tabard

2,3

and Elise Lavou

´

e

1,3

1

University of Lyon, Universit

´

e Jean Moulin Lyon 3, Iaelyon School of Management, France

2

University of Lyon, Universit

´

e Claude Bernard Lyon, France

3

CNRS, LIRIS UMR5205, F-69621 Lyon, France

4

Woonoz, Lyon, France

Keywords:

Learning, Dashboards, Design Study, Field Study.

Abstract:

Teachers mixing in-class and remote online learning activities face numerous challenges in monitoring learners’

online activity and progress, especially when preparing in-class interventions. We present a design study of

PROGDASH, a dashboard enabling teachers to monitor learners’ activity on an online grammar and spelling

learning platform. We designed PROGDASH based on interviews with seven teachers to understand their needs,

and we collaboratively iterated on design prototypes. We conducted a three-month field deployment with 17

teachers, collecting logs, diaries, and interview data to evaluate how PROGDASH informed their practices. Our

findings extend prior work on teachers’ practices using dashboards: teachers found PROGDASH actionable to

devise informed pedagogical practices: monitoring, conducting assessments, planning interventions, sharing

in-class, providing debriefing and feedback. Based on our findings, we suggest directions on how dashboards

could effectively support teachers in schools using online learning platforms in authentic settings.

1 INTRODUCTION

Schools are increasingly integrating web-based learn-

ing environments with in-class learning activi-

ties (Technavio, 2016). Teachers leverage these plat-

forms, to support in-class learning, help learners de-

velop skill-sets that should already be mastered, or to

provide personalized support to learners with specific

needs, e.g., dyslexics.

Teachers mixing in-class and remote online learn-

ing activities face numerous challenges in monitoring

learners’ online activities, especially when inform-

ing their in-class interventions. Dashboards can be

efficient tools for facilitating sense-making, reflec-

tion, and making informed decisions (Verbert et al.,

2014). Prior work on virtual learning environments,

used mainly in-class, has shown the potential of dash-

boards to support teachers, for instance, to improve

their awareness of their classrooms (Holstein et al.,

2018), to support their planning tasks and interven-

tions (Xhakaj et al., 2017), to support learners with

lesser abilities (Molenaar and van Campen, 2017), and

to provide personalized support to learners in a timely

fashion (Aslan et al., 2019).

However, with online learning, the individualized

pacing of learners makes it difficult for teachers to

monitor learners’ progression before engaging in for-

mative in class interventions. The way teachers lever-

age dashboards in the long run and how dashboards

shape their pedagogical practices is still unclear. Two

recent systematic reviews of more than 150 learning

analytics dashboards emphasize the need for more lon-

gitudinal studies to investigate how a dashboard might

inform and impact teachers’ practices (Bodily et al.,

2018; Schwendimann et al., 2017).

In this paper, we present a design study (Sedlmair

et al., 2012) and a longitudinal field evaluation of

PROGDASH, a dashboard to assist teachers in mon-

itoring learners’ progression on an online grammar

and spelling learning platform. We designed PROG-

DASH based on interviews with seven teachers to un-

derstand their needs, and we collaboratively iterated

on design prototypes (Dow et al., 2011). We imple-

mented and integrated PROGDASH in a commercial

online learning platform called PROJET-VOLTAIRE

1

.

We then conducted a three-month field deployment

with 17 teachers, collecting logs, diaries, and inter-

view data to evaluate how PROGDASH informed and

impacted their practices in blended learning. Our re-

sults show that most teachers reacted positively to the

dashboard. They found it actionable to inform sev-

1

https://www.projet-voltaire.fr

Ez-zaouia, M., Tabard, A. and Lavoué, E.

PROGDASH: Lessons Learned from a Learning Dashboard In-the-wild.

DOI: 10.5220/0009424801050117

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 2, pages 105-117

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

105

eral pedagogical practices: monitoring, conducting

assessments, planning interventions, sharing in-class,

providing debriefing and feedback. Our results fur-

ther highlight a divide between teachers specialized

in the concepts of the learning platform (i.e. French

language) and those in disciplines requiring the skills

(e.g. Marketing), even if both were concerned with

achieving the same objectives, mainly helping learners

master spelling and grammar. Based on our findings,

we provide design implications aimed at improving

dashboards to bridge online and in-class learning and

foster learners’ self-reflection.

The contributions of our work are (1) a design

study of PROGDASH to support teachers in using a

curriculum-integrated online learning platform, (2) a

three-month “in-the-wild” field study of PROGDASH,

which extends our understanding of how teachers inte-

grate a dashboard in their practices to articulate remote

and in-class learning, and (3) design implications for

dashboards to bridge online and in-class learning and

facilitate data-informed pedagogical practices.

2 RELATED WORK

This paper focuses specifically on how dashboards

might inform teachers’ practices in authentic settings.

2.1 Learning Analytics Dashboards

Early work on learning dashboards focused on support-

ing formative assessments to provide teachers with

data-driven insights into learners’ state of learning

(Black and Wiliam, 1998). Follow-up research on

learning dashboards focused on leveraging human

judgment through robust reporting tools and visual-

izations (Siemens and Baker, 2012). Recently, a wide

range of contributions has been introduced to instru-

ment teachers using dashboards spanning a variety of

aspects.

A great deal of research has been devoted to ensure

the solid technical infrastructure of dashboards, such

as standard ways to collect, store, and query learning

traces with the associated context and content, im-

plementation of interoperable architectures (Dyckhoff

et al., 2012), development through toolkits (Kitto et al.,

2015), and data aggregation from multiple learning

platforms (Mottus et al., 2014). Besides, other dash-

boards’ aspects have been investigated, such as en-

abling teachers to personalize the presentation of views

(Dyckhoff et al., 2012; Mottus et al., 2014; Michel

et al., 2017), or to specify what and how indicators are

monitored to match learners’ performance with regard

to competences (Florian-Gaviria et al., 2013).

While these studies shed light on the importance

of dashboards in assisting teachers, they mainly focus

on evaluating the technical aspects of the underlying

systems (Schwendimann et al., 2017). In fact, the

aforementioned dashboards and many others focused

mainly on “usability” (Chetlur et al., 2014; Dyckhoff

et al., 2012; Ez-zaouia and Lavou

´

e, 2017; Carrillo

et al., 2017), “usefulness” (Florian-Gaviria et al., 2013;

Dyckhoff et al., 2012), or “interoperability” (Dyckhoff

et al., 2012), and in many cases the evaluation was con-

ducted in controlled settings or even in the lab (Mazza

and Dimitrova, 2007). Although these studies are use-

ful for understanding the design and intelligibility of

dashboards, they teach us little about the impact of

dashboards on teachers’ practices in-situ.

Very few studies have focused on teachers’ rou-

tines surrounding such tools (Greiffenhagen, 2011), or

on how they are can guide teachers’ actions. And such

studies are often conducted over short-term deploy-

ments. In contrast, we conducted a teacher-centered

design process, leading to a longitudinal study, to in-

vestigate how a dashboard might impact teachers’ ped-

agogical practices in a long term (Ez-zaouia, 2020;

Zapata-Rivera and Katz, 2014).

2.2 Authentic Setting Studies

Research on teachers’ data-informed practices using

dashboards focuses mainly on how to support moni-

toring of learners’ performance while they are using a

learning environment in-class, such as errors, struggles,

attempts, responses, and engagement indicators. Com-

bining field observations and interviews, Molenaar

and van Campen (2017) investigated how 38 teachers

used a dashboard over one session (50 minutes) to

conduct assessments both at class and learner levels

(errors, progression, etc.), to provide motivational and

formative instruction to learners, as well as to adjust

both the learning material and the pace of the lesson.

Although the results revealed a diversity of use (low,

medium, high), three-quarters of teachers’ dashboard

consultations were followed by motivational feedback

or formative instruction either directed to the class as

a whole or to individual learners with medium or high

ability. In a similar study, Holstein et al. (2018) in-

vestigated how 8 teachers used a virtual reality glass

dashboard over a total of 18 courses (30 minutes each)

to orchestrate the classroom. In contrast to (Molenaar

and van Campen, 2017), the authors found that the

dashboard tended to divert teachers’ attention and time

towards learners of lower prior ability.

Combining observations and interviews, Aslan

et al. (2019) investigated how a teacher used indica-

tors of learners’ engagement shown on a dashboard

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

106

over two courses (80 minutes each) to support learners

through different teachers’ interventions: verbal warn-

ing, positive reinforcement, scaffolding, close moni-

toring. The authors observed a medium size-effect of

the dashboard on teachers’ scaffolding interventions

and use for close monitoring, mainly in assisting the

teacher with allocating time to learners who need most

support without compromising the overall experience

of the class. In a similar study, Martinez-Maldonado

et al. (2015) investigated how three teachers used real-

time notifications on learners’ actions and their learn-

ing artifacts, shown on a dashboard. The dashboard

was found to be helpful for teachers in orchestrating

multi-tabletop learning environments and providing

feedback to learners.

In a context similar to ours, Groba et al. (2014) pro-

posed an analytics-based tool to help teachers assess

learners’ activity, and evaluated it with two teachers

during a one-session course. The results showed that

this tool reduced significantly assessment times and

helped teachers understand the learning process of

learners. Combining think-aloud and observations,

Xhakaj et al. (2017) investigated how five teachers

used a dashboard to plan and conduct lessons over

eight courses (60 minutes each), where students used

a virtual learning environment. The authors found that

the provision of both positive and negative notifica-

tions on learners’ status facilitated the dialog between

a teacher and learners, and supported teachers in ad-

justing and orchestrating learning materials. The au-

thors also observed that the dashboard helped teachers

update (confirm, reject, and/or add new items) their

knowledge about both the class as a whole and indi-

vidual learners. In particular, the authors found that

teachers mostly integrated the knowledge acquired

concerning where learners’ struggles in their lessons.

These studies show that dashboards, when they are

well crafted, can successfully assist teachers in moni-

toring learners and conducting adapted interventions.

In fact, the aforementioned dashboards are mostly used

by teachers synchronously inside the classroom while

learners are using the computer-based learning envi-

ronment. Informed by the work of Ez-zaouia et al.

(2020), we investigate how PROGDASH may inform

teachers’ practices in blended and remote online learn-

ing settings. We sought to understand what teachers

actually do with dashboards “in-the-wild”.

3 DESIGN STUDY PROCESS

We followed a teacher-centered design study pro-

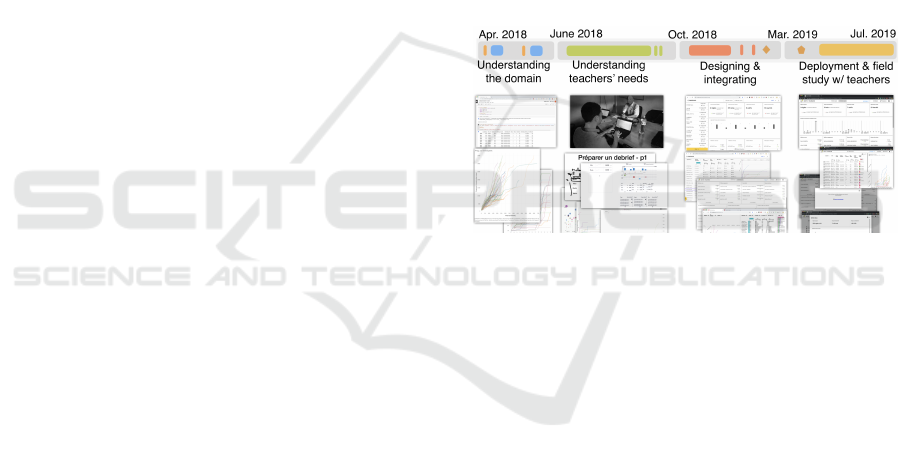

cess (Ez-zaouia, 2020) in four steps (Figure 1):

1. Understanding the Domain:

We discussed with

PROJET-VOLTAIRE designers to understand the the

platform, the exercises, the learning process, and its

data (see Section 4). We gathered real data to prototype

realistic visualizations.

2. Understanding Teachers’ Needs:

We interviewed

seven teachers to identify their needs for monitor-

ing/understanding learners’ progression, and to ex-

plore design alternatives (see Section 5).

3. Design and Implementation:

We iteratively de-

signed PROGDASH, which we then enhanced through

several informal discussions with members of the com-

pany and teachers from our first interviews. We de-

ployed a stable design of PROGDASH to the company’s

R&D team for usability feedback (see Section 6).

4. Field Study:

We conducted a three-month field

study with 17 teachers to capture teachers’ experi-

ence/perception of PROGDASH, and how it may assist

them in informing their practices (see Section 7).

Figure 1: Key steps of PROGDASH design process.

4 PROJET-VOLTAIRE PLATFORM

We collaborated with PROJET-VOLTAIRE, an online

platform for learning French vocabulary, grammar and

spelling rules. The platform is widely used by French

public and private schools (primary, middle, high

school and university). It can be used autonomously

or in-class, either projected on a whiteboard with class

exercises, or on personal computers.

Learning Process:

The platform centers around an

exerciser that adapts to learners’ skills in vocabulary,

spelling, and grammar. Learning is structured around

modules corresponding to a given level of expertise.

Each module has a set of stages that learners must

go through to master the level. A stage has a set of

grammar/spelling rules, corresponding to the concepts

that learners need to master. Each rule has a set of

exercises. Figure 2 shows typical questions on PROJET-

VOLTAIRE. Teachers can also set up class quizzes, i.e.,

short evaluations, typically carried out at the beginning

or the end of a course. PROJET-VOLTAIRE collects

the pertinent learning traces on learners (see Table 1),

PROGDASH: Lessons Learned from a Learning Dashboard In-the-wild

107

Figure 2: Example of exercises in PROJET-VOLTAIRE.

Table 1: PROJET-VOLTAIRE’s collected logs.

Attribute Description

Module Learning module(s) a learner is enrolled in

Stage level of difficulty of the module

Rules to master in each module

Exercises associated to a rule

Answers exercises’ answers (correct/incorrect)

Time-spent Time-spent to answer each exercise of a rule

which we used to build PROGDASH.

Learning Data:

Prior to our study, teachers had ac-

cess to a reporting table (see Figure 3). The table listed

learners with a set of indicators split across multiple

columns: time spent, score (%) of learner’s mastery,

initial level, scores and time spent on the programmed

quizzes, last connection, and rules acquired. Teachers

can also download a pdf report about each learner or

export the entire table as a spreadsheet file.

Figure 3: Example of a class report table.

5 TEACHERS’ NEEDS, AND

DESIGN GOALS

We conducted nine interviews with seven teachers to

understand (1) how they use the learning platform,

and (2) how they monitor learners’ progression. We

recruited teachers via the company’s education cus-

tomers’ team, and they received a book on the French

language as a thank-you gift. Interviews were audio-

recorded, and later transcribed and analyzed by the

main author to identify requirements in supporting

teachers.

Context of Use:

We identified three ways of how

teachers integrate PROJET-VOLTAIRE in their class-

rooms. First, as a learning material, they incorporate

platform-based activities in their curriculum with a

dedicated time-slot. Second, as a support material,

where teachers push learners to use the platform along-

side their course. And, finally, as a personalized aid

for specific learners, such as learners with grammar-

related disabilities, e.g., dyslexia, or with very poor

grammar skills.

Learning Progression:

Teachers characterize learn-

ers’ progression as (1) the levels and modules that

learners have reached, (2) the regularity of their prac-

tice, and (3) how skills develop over a period of time.

They highlighted the temporal nature of the learners’

progression, this is “hidden” in the existing reporting

table which displays only learners’ current state. This

causes learners’ progression – in sense of, e.g., unique

pathways, discrepancies, common strategies, similar

struggles; to become difficult for teachers to grasp.

Teachers reported relying on informal discussions with

learners to infer their progression and regularity of us-

ing the platform.

Informed Interventions:

Teachers often conduct inter-

ventions in-class to congratulate, encourage, remind,

or alert learners. They highlighted the complexity of

using the existing reporting table to keep track of learn-

ers’ online activity and to pinpoint gaps in learners’

progression, which hindered engaging in informed in-

terventions with learners, e.g., acquiring arguments for

debriefs and feedback. Also, when preparing a French

class, teachers expressed interest in knowing which

grammar concepts were not mastered by learners or

those that proved most tricky in order to tackle them

in class.

We derived the following design requirements from

our interviews:

R1:

Offer at-a-glance indicators to facilitate monitor-

ing of learners’ activity at class level by providing

summaries of learners’ overall practice, engagement,

and regularity in using the learning platform.

R2:

Provide indicators about learners’ practice to facil-

itate close monitoring at learner or group of learners’

level. Teachers emphasized the need for practicable

information enabling them to keep track of the status

of learners’ online activity on the platform.

R3:

Incorporate indicators about skills, i.e., grammar

concepts that are already mastered or prove challeng-

ing. In order to prepare class interventions or to help

individual learners, teachers expressed the need to un-

derstand what they should focus their interventions on,

based on learners’ difficulties.

R4:

Provide information about learners’ progression

over time. Teachers expressed the wish to grasp the

progression and regularity of practice over time. Learn-

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

108

ers’ progression is multifaceted and depends on how

teachers and learners engage with the learning plat-

form. Relevant indicators include grammar concepts

mastered, time spent, and amount of exercises prac-

ticed.

6 PROGDASH USER INTERFACE

The main challenge in designing PROGDASH was

to condense all the information required in a small

visual space in order to clearly and directly inform

teachers about the state of learners’ progression. Fol-

lowing “overview first, zoom and filter, then details

on-demand” (Shneiderman, 2003), we structured the

information in four different views so that teachers

can drill down for more information as needed. We

adopted statistical and visual summarization tech-

niques (Sarikaya et al., 2018) to present relevant indi-

cators.

PROGDASH compiles metrics over the last 7 or the

last 30 days, and teachers can pick between these two

temporal windows. We combined textual, visual, and

color encoding when designing the dashboard to facili-

tate glanceable reading of the indicators. We provided

comparison and contextualization of PROGDASH’s in-

dicators by using bars to encode cells in tables and

line-charts to visualize learners’ progression paths. We

also added histograms and bar-charts in the headers

of tables’ columns to facilitate filtering and searching.

We provide supplementary online material about the

dashboard in this link.

Main View:

This view (Figure 4.A) presents overall

information to monitor learners’ activity at class level

(

R1

). It presents 12 metrics in a grid compiled for

the selected time window (7 or 30 last days, see Fig-

ure 4.a1). The grid is structured around three topics on

learning regularity, learners’ progression, and gram-

mar rules acquisition (see Table 2). The first row of

the grid provides the average number of acquired rules

per learner, the time spent as well as the total number

of active/inactive learners. The same widget is used to

show the name, the value, and the associated (+/-) delta

– change since the previous time window (7 or 30 days),

of each metric. The second row shows a timeline bar-

chart of learners’ connections per day. The third row

displays learners’ related metrics: score, commitment,

help, and dropout. The same widget is used to present

the full name of the learner, as well as the associated

value and (+/-) delta. The last row presents grammar

rules related metrics: in focus (currently in learning

by learners), acquired (already learned), and known

(already known) (Figure 4.B). The rules are sorted by

their level of difficulty exhibited by learners’ practice.

Table 2: Main view’s indicators within 7 or 30 days.

Attribute Description

Learning Regularity

Grammar

Rules

Avg. number of mastered grammar rules per learner, with the associ-

ated (+/-) delta of the selected time (Figure 4.a2).

Time Spent Avg. time spent learning per learner, with the associated (+/-) delta of

the selected time window (Figure 4.a3).

Active Learn-

ers

Number of active learners, with the associated (+/-) delta. Learner is

considered active if s/he makes at least one (in 7 last days) or 4 (in 30

last days) connections (Figure 4.a4).

Inactive

Learners

Number of inactive learners, with the associated (+/-) delta. Learner is

considered inactive if he/she makes zero (7 last days) or less than 4 (30

last days) connections window(Figure 4.a5).

Connections

Timeline

Total some of unique connections per day (Figure 4.a6).

Learners Progression

Score Top five learners in grammar rules acquisition (Figure 4.a7).

Commitment Top five learners in practicing on the platform (Figure 4.a8).

Help Top five learners struggling the most (Figure 4.a9).

Dropout Top five non-practicing the most (Figure 4.a10).

Grammar Rules Acquisition

In Focus Top five rules currently in acquisition, and leading to struggles to most

learners (Figure 4.a11).

Acquired Top five rules already acquired, although led to struggles to most

learners (Figure 4.a12).

Known Example of five rules already known by most learners (Figure 4.a13).

Teachers can select a set of rules and launch

Prac-

tice view

to practice them with learners live in-class

(Figure 4.C) (R3).

Practice View:

This view (Figure 4.E) enables close

monitoring of the most important indicators on learn-

ers’ activity at an individual and group level (

R2

). It

displays the list of learners in the class with a set of

associated metrics (learners’ Fullname, Score, Time

spent, Connections, Initial level score, Initial evalua-

tion score, Reached module) arranged in a tabular form

(see Table 3). The column headers are displayed ei-

ther as a histogram or a bar-chart according to whether

the column is categorical or nominal. Similarly, the

cells are encoded using bars to support comparison

between learners. Interaction with the headers through

filtering and sorting is provided to support searching

and to make scanning information easier. The table is

augmented with a line-chart of learners’ learning pro-

gression pathways in a timeline of all learning modules

in which learners may enroll (R4).

Evaluation View:

This view (Figure 4.D) displays the

list of learners’ metrics related to their evaluations, i.e.,

quizzes programmed by teachers (

R2

), in the same

Table 3: Practice view’s indicators.

Attribute Description

Learner Learner’s full name (Figure 4.e1).

Score Learner’s current score, that is, the number of rules known

+ acquired over the total number of rules in his/her learning

path, as both a percentage and a total number (Figure 4.e2).

Time Spent Time spent practicing on the platform (Figure 4.e3).

Connections Total number of connections on the platform (Figure 4.e4).

Last connection Last connection, as: since x hour/day/month(s)(Figure 4.e5)

Initial level Grammar rules that are initially known by a learner, as both a

percentage and a total number (Figure 4.e6).

Initial Evaluation Score at initial evaluation as a percentage of correct answers

(Figure 4.e7).

Reached Module Last module reached by learner in his/her learning path

(Figure 4.e8).

PROGDASH: Lessons Learned from a Learning Dashboard In-the-wild

109

Figure 4: PROGDASH user interface.

tabular form as the Practice view. This includes the

learner’s name, the time spent on the evaluation, the

score obtained, as well as a corresponding derived

score on a scale of 20 (Figure 4.d1–5).

Learner View:

This view (Figure 4.F) is shown as a

dialog box that presents the main metrics of the learn-

ers in a grid form, in a similar way to the Main view.

This includes the current score, the time spent, the total

number of initially known rules, the learning progres-

sion line-chart, as well as grammar rules acquisition

related metrics (top five rules in focus (currently in

learning by learners), acquired (already learned) and

known (already known) (R2, R3).

Implementation:

PROGDASH user interface is built

using Typescript and Angular. The visualizations are

implemented using D3js. PROGDASH works in a

client/server fashion over REST web services. We

pull the data from the database and compile metrics of

the different views, before serving back to the browser

in JSON. For optimization purposes, data is cached on

the client for 1h before refreshing.

7 FIELD STUDY DESIGN

We deployed PROGDASH for three months between

March and June 2019. We aimed at investigating how

teachers used the dashboard to monitor learners’ pro-

gression. Specifically, we sought to answer two main

research questions:

•

Does PROGDASH provide teachers with useful in-

formation about learning progression?

•

How does PROGDASH inform teachers’ practices

in assessing learners’ online learning and conduct-

ing formative interventions?

7.1 Procedure

Deployment lasted three months for each teacher, split

into 3 phases: opening, deployment, and closing.

Participants:

We recruited 17 teachers via the

company’s newsletter (gender: [F=10, M=7], age:

[min=30, max=60], school: [Middle=6, High=4, Vo-

cational=7]). They all used PROJET-VOLTAIRE with

their learners. We informed teachers of the logging

implemented on the dashboard and their ability to with-

draw at any time. They gave us permission for collect-

ing and analyzing data.

Opening:

We started the study after we had recruited

11 participants. We continued to enroll participants

for two weeks afterwards. In the first week, we set

up a webinar as teachers resided in different locations.

We explained the main objectives of the study as well

as the different parts of PROGDASH to help them be-

come familiar with it. The webinar was recorded and

later shared, along with a pdf user guide, with all the

participants when they joined our study.

Deployment:

We informed the teachers that they

could use PROGDASH for a three-month period us-

ing dedicated web instance. Teachers used their own

devices to access the dashboard from their location.

Closing:

At the end, we asked the participants to fill

out a questionnaire to collect feedback about the use-

fulness and effectiveness of PROGDASH, as well as

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

110

teachers’ practices. Later, a member of our research

team set up online semi-structured interviews with six

teachers. The interviews lasted 30 to 50 minutes. The

questionnaire and interviews focused on (1) teachers’

overall experience and perception in using PROGDASH

and (2) how teachers used the tool in practice.

7.2 Data Collection and Analysis

Logs:

We captured teachers’ actions on PROGDASH

with the associated timestamps.

Questionnaires:

During the opening, we asked the

participants to fill out a profile questionnaire to col-

lect demographics information. During the deploy-

ment phase, each week, we asked teachers to fill out

a simple diary questionnaire, asking if they had used

PROGDASH the week before, when and what for. We

gathered 16 (out of 17) participants’ responses to the

profile questionnaire, a total of 76 diary entries where

teachers reported whether or not they had checked

PROGDASH during the week [many times = 24 en-

tries, once = 15, no checks = 36], and 14 (out of 17)

responses to the ending questionnaire.

Interviews:

We audio-recorded the interviews and

followed Braun and Clarke (2006) thematic analysis:

1. Familiarizing with Data:

We manually transcribed

and pseudonymized the interviews. We then allocated

notes to interesting excerpts.

2. Initial Coding:

We transferred excerpts to a spread-

sheet and assigned them codes. We kept enough con-

text to ensure proper understanding. We duplicated

excerpts with multiple codes. We iterated on codes to

converge towards coherent sets.

3. Identifying Themes:

We iteratively piled and orga-

nized codes into themes, resulting in 20 initial themes.

4. Reviewing Themes:

We created a theme map from

the initial themes, which we discussed among co-

authors as suggested by (McDonald et al., 2019). We

decided to split some themes and to merge others,

resulting in 6 main themes. We kept representative

excerpts for each theme to ensure coherence.

5. Naming Themes:

We named and defined each

theme by its set of code excerpts. We then reviewed

coded excerpts to refine the reporting on each theme.

8 FIELD STUDY RESULTS

8.1 Teachers’ Overall Use

Participants’ interaction with PROGDASH evolved over

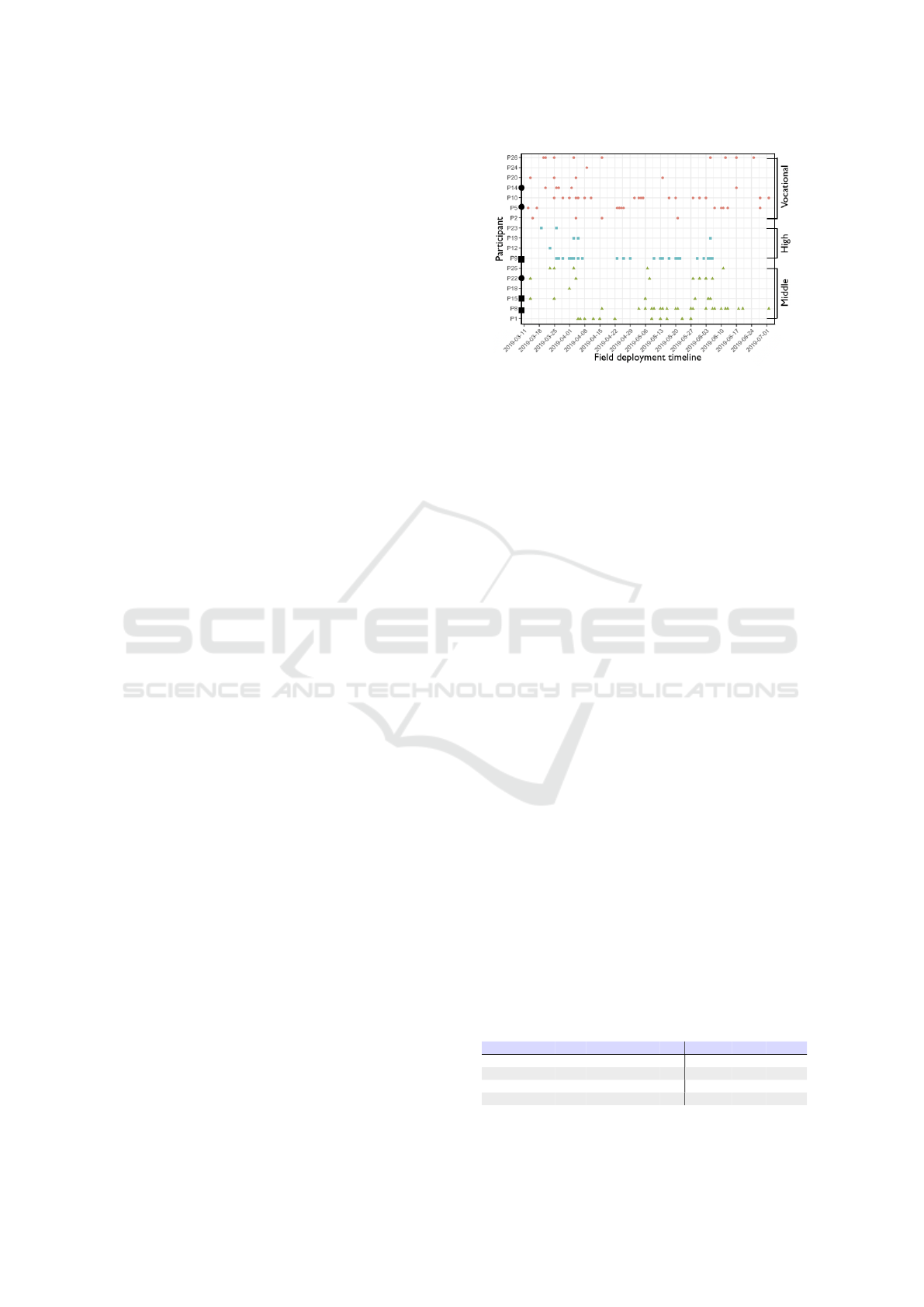

the course of the deployment. Our log data (Figure 5)

Figure 5: Teachers’ sessions using PROGDASH. Interviewed

teachers are marked with squares for French language teach-

ers, and with dots for other teachers.

shows less activity at the end than at the beginning of

the experiment, with school holidays in April account-

ing for a lesser use for two weeks.

Connections.

Log data showed that all teachers used

PROGDASH at least once. The 17 participants used the

tool 274 times in total [min=1, max=72, mean=16.1,

sd=21.2] (identified as accessing the dashboard and se-

lecting a class from the menu to explore AND counting

only single login sessions). P1 asked to withdraw after

using it 17 times, s/he explained that the dashboard

did not suit her/his needs of dealing with 25 groups of

learners, which s/he preferred to handle directly with

spreadsheet exports. Three teachers used it only once

(P12, P18, P24). Thirteen teachers used PROGDASH

three or more times.

PROGDASH Views.

Teachers used mostly the Main

and Practice views, followed by the Learner view, than

the Evaluation view (Table 4). Teachers in middle

schools used the Learner view less than in high or vo-

cational schools, mostly due to P9’s and P10’s exten-

sive use of it. In the post-questionnaire (14 responses

out of 17 participants), teachers expressed interest in

all PROGDASH’s views (Figure 6).

Teachers’ Overall Experience.

We asked teachers in

the post-questionnaire: “Would you like to continue

using the dashboard?”. All 14 out of the 17 who

filled out the questionnaire responded “Yes”. Simi-

larly, we asked participants “Would you recommend

the dashboard to a colleague already using PROJET-

VOLTAIRE?”, and their average rating (out of 14 re-

sponses) was above four on 5-point Likert scale. Over-

Table 4: Use of PROGDASH’s views, as count (#).

View Count Min Max Avg SD Vocational High Middle

Main view 300 1 73 17.6 22.8 100 81 119

Practice view 309 1 72 19.3 23.1 112 77 120

Learner view 207 1 137 18.8 39.8 37 33 137

Evaluation view 150 1 60 11.5 16.6 55 63 32

PROGDASH: Lessons Learned from a Learning Dashboard In-the-wild

111

Figure 6: Teachers’ interest in PROGDASH’s views and indi-

cators on a scale of 0 to 5 with the confidence interval.

all, teachers were satisfied. They highlighted in their

diaries different features of PROGDASH, such as the

(1) visual aspect of the dashboard: “I like the graphics”

(– P5), “visual aspect of the class” (– P20), (2) learn-

ers’ progression: “progression line-charts are very

interesting” (– P22), “quick way to visualize learn-

ers’ trajectories or their connection to the platform”

(– P12), and (3) grammar acquisition: “ability to see

easily the levels learners reached and the number of

concepts acquired by each learner” (– P1), “many

more details and vision about learners who do nothing

to target them with exercises to do” (– P15).

Teachers’ Pain-points and Suggestions.

In their di-

aries and interviews participants noted some usabil-

ity issues and reported several suggestions. Teachers

wanted to identify learners who missed an evaluation

session. They had to look for blank cells in the ta-

ble to find those learners, which became tedious with

multiple evaluations per learner.

P22 stated that teachers must often cope with tech-

nical problems in the classroom, turning on the com-

puter, connecting, setting up PROGDASH, or any other

tool becoming too time-consuming. S/he suggested

simplifying it by making two modes: “a simple mode

and an expert mode. The simple mode needs to be

really ultra simple and ultra direct to track learners’

results, and when you want to move on to something

more advanced you can.” (– P22). S/he added by

pointing out the need for an automated weekly report

that could be sent by email to teachers as it might be

more practical to access and to use on his/her mobile

phone.

P14 highlighted his/her frustration with the design

of the grammar acquisition view as s/he needed to

be able to assign asynchronously specific concepts so

that learners could practice those concepts when they

launched the learning platform.

Table 5: Summary of teachers’ pedagogical practices

through the use of PROGDASH.

Teachers’ practices along with illustrative quotes

Monitoring learners’ progression

I really rely on the line-charts, I find them very telling [..] and immediately I see who

dropped out or not, after I look at the numbers, but I start by looking at the line-charts.

– P8

Often when I conduct my monitoring review, once a month, actually, I will dig deeper

[..] I will rather be in the exploratory but regarding a particular learner. – P14

Formative, Summative Assessments

Now, when we have the detailed list of all the [grammar] concepts, we know precisely

that if the learner no longer has this concept which is displayed – it means that it is

acquired [..]. Before s/he [a learner] used PROJET-VOLTAIRE yes! but what value?

does s/he learn no! we had to evaluate and conduct an evaluation. – P15

When we fill out learners’ transcripts in the school, there is a criterion: the ability

to ex-press oneself in writing with clarity and accuracy; of course, here we have

objective elements [meaning using PROGDASH] to check the boxe. – P9

Planning, Adjusting Interventions

We had planned to work on the homophones “en” and “on” and when I saw that it

was acquired by everybody, we did not do it. – P15

I use [PROGDASH] to adapt things when I realize that a language [grammar] element

is not mastered at all, I will change my plan to incorporate it. – P8

Sharing PROGDASH In-class With Learners

They [Learners] were pleading to have such information, to see how they progress. –

P8

I showed [PROGDASH] to learners [..] telling them that I could see everything that

happened. And, when they knew it, it changed [learners’ pace], because they didn’t

think we had access to it. – P15

Providing Feedback to Learners

It is rather to motivate them [learners], but it is also to sanction those who do not do

their job. – P8

I didn’t do a lot of close or individual monitoring with them [learners] except remind-

ing them that they had to use the app. – P14

P8 and P9 disagreed with the sampling choice of in-

dicators in the main view. For instance, P9 stated: “top

5 is not enough because it needed to be balanced to 35

[number of learners in the class], it must be a top 10”.

Similarly, regarding the top 5 samplings of grammar

concepts, P8 stated: “I really like to be able to choose

what I give to learners using PROJET-VOLTAIRE live

in the classroom”. Drawing a parallel with learners’

progression line-charts, P8 and P22 requested a time-

line for learners’ time spent on the platform.

8.2 Teachers’ Pedagogical Practices

Table 5 provides an overview of the pedagogical prac-

tices teachers developed with PROGDASH, and consid-

ered helpful.

Monitoring Learners’ Progression.

According to

log data, 13 (out of 17) teachers checked the dash-

board three or more times to monitor learners’ activity

on the learning platform (see Figure 5). Overall, in

their diary reporting, those teachers reported a total

of 35 checks of PROGDASH before a class [min=1,

max=8, mean=3.18, sd=2.08]. They reported doing

so to check learners’ status and to look for outliers,

either to encourage those practicing most or to talk

to those not practicing enough. Teachers used such a

strategy to provide the whole class with feedback . In

post-interviews, P8 stated: “I start by looking at the

line-charts, and I see who is doing very well – to be

able to congratulate and encourage them and who is

not doing too well. It allows me to talk to them the

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

112

next day when I see them”.

Eight teachers reported in their diaries that they

checked PROGDASH during a class a total of 27

times [min=1, max=8, mean=3.37, sd=2.26]. In post-

interviews, two French teachers (P9, P15) emphasized

checking the dashboard during a class, while learners

were working on the learning platform, to check dis-

crepancies between learners’ progression in grammar

concept acquisition. P9 stated: “during the class when

they are in training, at a given time, I tell everyone to

stop where they are. I now have the goal to harmo-

nize the progression of the class, so I point to the gaps

between learners”.

Additionally, 13 teachers reported in their diaries

checking PROGDASH after a class for a total of 26

times [min=1, max=5, mean=2.00, sd=1.29]. Teach-

ers did so to inform follow-up debriefs with learners,

or just to check if learners were progressing as ex-

pected. In post-interviews, P15 stated looking at the

dashboard to check whether a learner had practiced a

list of grammar concepts using the platform: “I check

the next week, if s/he still has the same list [of gram-

mar concepts], then we will talk”. Teachers looked at

different dashboard indicators depending on the type

of interventions they anticipated. Learners’ time spent

on the platform was one of the most important indi-

cators for all teachers (see Figure 6). French teachers

who teach material related to grammar concepts or

who even use the learning platform in class, were inter-

ested in monitoring a combination of indicators about

learners’ progression, namely, the time spent on the

platform, the regularity of learning, pacing, and skills

development (P8, P9, P15).

Furthermore, teachers relied primarily on the line-

chart timeline to conduct overall monitoring first be-

fore drilling down for more details. In post-interviews,

four (out of six) teachers (P8, P5, P14, P22) high-

lighted the effectiveness of the line-charts in com-

paring learners’ progression and identifying extreme

learners: “the line-charts representation is interest-

ing because in the blink of an eye we can have the

progression of learners compared to each other” (–

P14). Three teachers (P8, P5, P14) stated that they

started their monitoring from the line-charts and then

looked at the numbers: “I really rely on the line-charts,

I find them very telling [..] and immediately I see who

dropped out or not, after I look at the numbers, but

I start by looking at the line-charts” (– P8). Finally,

two teachers (P14, P22) stated in post- interviews that

they conduct exploratory analyses using the dashboard.

P22 stated that s/he did so to explore out of curios-

ity: “it was mostly to see and do some monitoring, not

remediation. It was mostly to see [PROGDASH] out

of curiosity”. P14 stated that s/he often drilled down

regarding a specific learner: “often when I conduct

my monitoring review, once a month, actually, I will

dig deeper [..] I will rather be in the exploratory but

regarding a particular learner”.

Formative, Summative Assessments.

The dash-

board was instrumental to teachers as it provided on-

going feedback about learners’ online activity. This,

in part, supported teachers in conducting quick forma-

tive assessments about learners’ progression. In post-

interviews, P8 stated comparing without and with the

dashboard: “when I land on the dashboard, I see the

[grammar] concepts that are the most challenging for

learners [..] before I had to infer it, as learners were

the ones who informed me [during discussions]. Now

I have it directly on the dashboard: s/he [a learner]

doesn’t need to explain, and I see which concepts s/he

is struggling with”. Similarly, P15 stated: “[before

PROGDASH] we did not have the impression that we

have a value [from using PROJET-VOLTAIRE]. Now,

when we have the detailed list of all the [grammar]

concepts, we know precisely that if the learner no

longer has this concept which is displayed – it means

that it is acquired [..]. Before s/he [a learner] used

PROJET-VOLTAIRE yes! but what value? does s/he

learn [grammar concepts] no! we had to evaluate and

conduct an evaluation”.

Additionally, the dashboard supported teachers in

conducting summative assessments of learners’ pro-

gression at the end of the school year at the end of

some instructional unit. P9 described how the dash-

board provided objective facts for filling out evalua-

tion reports: “when we fill out learners’ transcripts

in the school, there is a criterion: the ability to ex-

press oneself in writing with clarity and accuracy; of

course, here we have objective elements [meaning us-

ing PROGDASH] to check the boxes”. Similarly, P8

stated using the dashboard to prepare a class council

meeting: “at the time of preparing the class council,

it allowed me to see [learners’ progression] in the

blink of an eye. It is a great tool to see whether learn-

ers’ work is steady over time, where s/he managed to

progress, where s/he didn’t”. On a class level, P15

reported using PROGDASH to evaluate grammar fun-

damentals among classes: “all the bottom part [of the

Main view] about [grammar] concepts [..], especially

the concepts that are already known [by learners], en-

abled us to see which classes had good fundamentals,

and that was interesting”.

Planning, Adjusting Interventions.

Teachers used

the dashboard to inform their in-class activities.

Among the 13 teachers who checked PROGDASH peri-

odically (three or more times), seven reported in their

diaries that they checked the dashboard to prepare a de-

brief. They also used it to adjust their teaching plans,

PROGDASH: Lessons Learned from a Learning Dashboard In-the-wild

113

assign work, or structure their classroom activities

(e.g., peer-tutoring).

In post-interviews, all the French teachers stated

that they used PROGDASH to adjust their lectures. P14

stated: “we had planned to work on the homophones

“en” and “on” and when I saw that it was acquired by

everybody, we did not do it”. Similarly, P8 stated: “I

use [PROGDASH] to adapt things when I realize that

a language [grammar] element is not mastered at all,

I will change my plan to incorporate it”. Only two

teachers (P15, P25) reported in diaries that they used

PROGDASH to prepare lesson content.

Teachers also used PROGDASH to target groups

of learners based on their difficulties. In fact, among

teachers who checked PROGDASH frequently (three or

more times), eight teachers stated that they look at the

dashboard to check the status of individual (or groups

of) learners. For instance, P14 stated: “what we found

interesting is having real information to know that this

learner has a problem with this rule, to be able to reuse

them in more individualized exercises in personalized

aid”. P9 stated “I will note on our digital working

space in bold characters, to tell them: ‘I warn you, I

checked the dashboard’. And, I will mark with a 56

font-size: ‘work on PROJET-VOLTAIRE’.”

In the post-interview, only P15 explained using

PROGDASH to set up peer-tutoring sessions: “I take

active learners [..] and I pick one learner with diffi-

culties and ask Paul [active one] to work with Pierre

[struggling], to show and explain”.

Sharing PROGDASH in-class.

The six teachers who

participated in post-interviews, stated that they used

PROGDASH to facilitate in-class debriefs, by showing

it to individuals or to the class. Two teachers (P8, P9)

stated that they shared the dashboard in-class to tell

learners about their indicators, and to enable them to

see their progression, as learners did not have access

to such information. P8 and P9 further reported that

learners “were pleading to have such information, to

see how they progress” (– P8) and they “ask to see

their line-charts” (– P9).

In post-interviews, five teachers (P8, P9, P15, P14,

P5) explained that they aimed at improving learners’

pacing by showing that they had indicators on their

practice on the learning platform. P15 stated: “I

showed [PROGDASH] to learners [..] telling them

that I could see everything that happened. And, when

they knew it, it changed [learners’ pace], because they

didn’t think we had access to it”.

Additionally, in post-interviews, all teachers re-

ported that they shared PROGDASH in-class to facil-

itate motivational debriefs with learners. Teachers

described different strategies to ensure that learners

maintain a steady practice. One was simply to al-

low learners to see their names among the top 5, or

bottom 5 learners, which, in part, helped stimulate

learners’ self-reflection and motivate them to practice

more. Similarly, P9 stated that showing the table in the

Practice view ordered by learners’ time spent online,

“triggered some sort of challenge, and they [learners]

worked harder”. Moreover, in post-interviews, all

teachers stated that they showed the progression of

line-charts to motivate learners. Its main role was

in “demonstrating the correlation” (P9, P22) between

practicing on a regular basis and learners’ progression.

Hence, showing progression over time was important

to emphasize the longitudinal nature of the learning

process. However, one teacher decided not to dis-

play the information to the whole class, and preferred

to provide one-to-one debriefs with learners, as s/he

thought that showing PROGDASH to the whole class

would stigmatize learners: “[PROGDASH] is some-

thing I keep for myself. I have to show it individually

[..] it stigmatizes learners, and right away they would

mock each other.” (– P5).

We did not anticipate that teachers would share the

dashboard live in-class. We discuss the ethical impli-

cations of such a practice in the discussion section.

Providing Feedback to Learners.

We identified dif-

ferent feedback strategies building on PROGDASH,

both at individual and class level. All the teachers

stated in the post-interviews that they reminded learn-

ers of the need to practice, often lecturing them briefly

about the importance of practicing on a regular basis

to maintain steady progress. Teachers either checked

learners’ status using PROGDASH before or during

a class to congratulate learners who were practicing

and provide public or private reminders to others who

were not. Moreover, French teachers in particular, con-

ducted individual debriefs with learners. For instance,

P9 stated: “I have split-classes, so I can do individual

debriefs. Learners come at the end of the class and ask

to see their line-charts”. Besides, feedback also took

the form of guidance regarding how to best use the

learning platform. P5 stated: “I tell them, take your

time [to read and understand grammar concepts], we

give you the concepts and examples so you can train

on short sentences, and after you can try again”.

In the post-interviews, teachers who did not teach

French (P14, P5, P22), reported that it was the learn-

ers responsibility to practice. They mostly provided

feedback regarding the efforts made by learners online

on the platform, e.g., time spent, and the number of

connections. Also, they often reminded learners of the

importance of mastering the language for their future,

or as stated by P14: “I explain to them their [future]

job, I train them to be assistant managers, so: ‘you

will have to write letters, emails [..]’ they will have a

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

114

lot of written production”. Non-French teachers used

the learning platform in addition to their classes, e.g.,

marketing and management. They stated having little

time to provide formative feedback, and also that they

did not feel competent in providing formative feedback

to learners regarding grammar concepts, as they are

not specialized in French grammar. For instance, P14

stated: “I do not feel qualified to explain a [grammar]

concept, or other things, because I do not necessarily

master it myself”.

Limitations and Future Work.

Although we aimed

at including in the study teachers from different disci-

plines, and levels, e.g., middle, high, and vocational

schools, to gather realistic insights into teachers’ prac-

tices in using web-based online learning platforms,

teachers were self-selected to participate in this study.

Therefore, the results may reflect practices of moti-

vated profiles of teachers. Additionally, we asked

teachers to fill out a diary by sending them a weekly

email, which may have pushed teachers to check the

dashboard. Finally, our study is exploratory in nature,

as the learning platform we collaborated with has a di-

verse context of use in schools, thus making it difficult

to derive representative pedagogical practices of teach-

ers in their use of the dashboard. The next step would

be, for instance, to conduct a study centered around

each profile of teachers with respect to their context of

use of the learning platform. Further work is needed

to understand: how our results may generalize to other

online learning platforms, what is the impact of the

dashboard on learners, and investigate the design of

dashboards that connect teachers, learners, and others.

9 DISCUSSION AND DESIGN

IMPLICATIONS

In this section, we discuss our findings in relation to

previous work. We also suggest design implications

for dashboards in online learning settings.

Providing Insights into Learning Progression.

Our

findings show that PROGDASH was instrumental to

teachers in accomplishing different tasks. First, in

terms of monitoring, the dashboard surfaced infor-

mation previously invisible, and confirmed teachers’

intuitions about learners’ online progression that they

built from formal or informal discussions with learners

in the classroom. This corroborates prior results, par-

ticularly in improving teacher “visibility” of (Groba

et al., 2014) and “knowledge” about (Xhakaj et al.,

2017) learners’ online learning.

Additionally, the dashboard supported teachers in

conducting formative and summative assessments of

learners’ activity both during and at the end of instruc-

tional units, which suggests that dashboards may help

reduce assessment time as found in (Groba et al., 2014;

Govaerts et al., 2011). PROGDASH particularly sup-

ported French teachers in identifying those grammar

concepts where learners struggle most, and in adjust-

ing learning materials accordingly as found in (Xhakaj

et al., 2017; Molenaar and van Campen, 2017).

Understanding Individual and Group Progression.

PROGDASH highlighted the large variability of learn-

ers’ progression in the classroom, enabled by indica-

tors that categorize learners (e.g., top learners) and

by temporal visualizations (e.g., line-charts), which

highlight patterns of tendencies among learners. Also,

this corroborates prior results on dashboards as en-

ablers to identify trends, for instance in forum discus-

sions (Mazza and Dimitrova, 2007), learners’ note-

books (Yuan et al., 2008), and learners’ regulation in a

social network (Groba et al., 2014).

Additionally, teachers emphasized the effective-

ness of line-charts in understanding the temporal pro-

gression of learners, which supported the identification

of outliers, as in (Mazza and Dimitrova, 2007; Mole-

naar and van Campen, 2017). Importantly, line-charts

enabled teachers to grasp and understand the unique

progression of each learner. Teachers started their ex-

ploration of the dashboard by looking at line-charts

and then at numbers, as reported in post-interviews.

Line-charts also supported the comparison between

learners’ progression (P8, P5, P14, P22).

Supporting Effective Data-informed Practices.

Our study underlines critical implications of use of

teachers’ dashboards in contexts like ours, namely, spe-

cialized online learning platforms. That is, even if all

teachers in this study used PROJET-VOLTAIRE to help

learners improve their grammar skills with associated

grades, there was a divide in PROGDASH use. Teach-

ers who used the platform in their French language

courses, relied on different indicators of learners’ pro-

gression, including grammar concept acquisition, and

conducted different informed pedagogical interven-

tions: debriefing, feedback, peer-tutoring, and lessons.

On the other hand, teachers who used the platform

while teaching other disciplines, relied mainly on in-

dicators about learners’ efforts, such as the amount of

time invested online and the number of connections.

They were reluctant to provide formative feedback to

learners, e.g., related to grammar concepts, and thus

mainly lectured and reminded learners to use the learn-

ing platform on their own.

As a result, for instance, the type of feedback given

by teachers could have a mixed-effect on learners. That

is, in post-interviews, all teachers emphasized that

they “congratulate” top learners, while all non-French

PROGDASH: Lessons Learned from a Learning Dashboard In-the-wild

115

teachers relied mainly on “timespent” to devise their

feedback. For example, praising learners for task per-

formance is shown to be ineffective as “it contains

such little learning-related information” (Hattie and

Timperley, 2007). In part, this suggests the need to

train teachers to better support the intended use of such

learning platforms through dashboards. Also, in part,

it suggests the need for dashboards to facilitate find-

ing teachable elements so that a teacher can provide

effective and actionable feedback about learners’ pro-

gression. In fact, teachers’ feedback is more likely to

work when it is supportive, timely, and, importantly,

specific to the learning activity (Shute, 2008).

Anticipating, Facilitating in-class Use.

PROGDASH

supported teachers in engaging in informed debriefs,

e.g., “positive reinforcement”, “verbal warning” to

push learners to do their best, as was found in (Aslan

et al., 2019). Importantly, teachers shared the dash-

board with the whole class to support their debriefs for

three main reasons: transparency, to share informa-

tion with learners as they do not have access to such

dashboards (P9, P8); control, to let learners know that

teachers have precise indicators about their progres-

sion and pacing (P8, P9, P15, P14, P5); and for motiva-

tion, to foster self-reflection and stimulate challenge by

showing learners’ indicators about their progression.

This is very important as the dashboard fostered the di-

alog between teachers and learners in both directions,

as in some classes, learners asked teachers to debrief

them regarding charts on the dashboard. Such dialog

improved the learning experience in the classroom,

which would be lost if, for instance, the dashboard

was designed only for learners (Martinez-Maldonado

et al., 2015), or if the feedback was automated, e.g.,

programmed to learners, a practice found to be inef-

fective (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). However, we did

not anticipate that teachers would show the dashboard

in-class for debriefing with learners, or show informa-

tion on all learners to the whole class, and PROGDASH

was not designed for this purpose. This raises design

and ethical concerns, especially regarding showing full

names, rankings and learning data of all learners.

Additionally, in post-interviews, teachers empha-

sized their use of the dashboard in-class to foster learn-

ers’ motivation and self-reflection. This is very im-

portant as most teacher-facing dashboards, even those

designed to be used in classrooms (e.g., synchronous),

are not designed to be shared with learners to support

debriefs or feedback, even though dashboards can have

a positive effect on learners, as was found in (Aslan

et al., 2019; Holstein et al., 2018). Besides, although

we did not intend to support self-reflection by design

through PROGDASH, this observation is in-line with

the impact model of learning dashboards proposed by

Verbert et al. (2014).

These findings suggest the need for dashboards to

support in-class sharing with individuals and groups,

or for focused teaching interventions. However, dash-

boards need to be carefully designed to anticipate this

kind of emerging teachers’ practices.

10 CONCLUSION

We presented a design study of a dashboard to support

teachers in monitoring learners’ progression on an

online grammar and spelling learning platform. We

iteratively designed the dashboard with teachers, and

we integrated it on a widely used platform. The result

of this work is PROGDASH.

We presented the results of a 3-month field study

of a dashboard in-the-wild, with 17 teachers, from dif-

ferent schools. Our results show that teachers used

the dashboard at different times (before, during and

after a course) and for different purposes: monitoring,

formative, summative assessments, and planning inter-

ventions. Teachers shared the dashboard with learners

for transparency, control, and motivational purposes,

to support debriefs and in-class interventions. Teach-

ers used PROGDASH to provide feedback to learners

at both class and individual level. Our results high-

light a divide between the practices of teachers teach-

ing French language and those using the platform for

extra-curricular learning. Based on our findings, we

suggest directions on how teachers’ dashboards could

better bridge online and in-class learning.

REFERENCES

Aslan, S., Alyuz, N., Tanriover, C., Mete, S. E., Okur, E.,

D

'

Mello, S. K., and Esme, A. A. (2019). Investigating

the impact of a real-time, multimodal student engage-

ment analytics technology in authentic classrooms. In

Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '19. ACM Press.

Black, P. and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom

learning. Assessment in Education: principles, policy

& practice, 5(1):7–74.

Bodily, R., Kay, J., Aleven, V., Jivet, I., Davis, D., Xhakaj,

F., and Verbert, K. (2018). Open learner models and

learning analytics dashboards: A systematic review. In

Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on

Learning Analytics and Knowledge, LAK ’18, pages

41–50, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis

in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology,

3:77–101.

Carrillo, R., Renaud, C., Pri

´

e, Y., and Lavou

´

e,

´

E. (2017).

Dashboard for monitoring student engagement in mind

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

116

mapping activities. In 2017 IEEE 17th Interna-

tional Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies

(ICALT), pages 433–437. IEEE.

Chetlur, M., Tamhane, A., Reddy, V. K., Sengupta, B., Jain,

M., Sukjunnimit, P., and Wagh, R. (2014). Edupal:

Enabling blended learning in resource constrained en-

vironments. In Proceedings of the Fifth ACM Sympo-

sium on Computing for Development, ACM DEV-5

’14, pages 73–82, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Dow, S. P., Glassco, A., Kass, J., Schwarz, M., Schwartz,

D. L., and Klemmer, S. R. (2011). Parallel prototyping

leads to better design results, more divergence, and

increased self-efficacy. In Design Thinking Research,

pages 127–153. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Dyckhoff, A. L., Zielke, D., B

¨

ultmann, M., Chatti, M. A.,

and Schroeder, U. (2012). Design and implementation

of a learning analytics toolkit for teachers. Journal of

Educational Technology & Society, 15(3):58–76.

Ez-zaouia, M. (2020). Teacher-centered design process.

Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Ex-

plainable Learning Analytics, Companion Proceedings

10th International Conference on Learning Analytics

& Knowledge.

Ez-zaouia, M. and Lavou

´

e, E. (2017). Emoda: A tutor ori-

ented multimodal and contextual emotional dashboard.

In Proceedings of the Seventh International Learning

Analytics & Knowledge Conference, LAK ’17,

pages 429–438, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Ez-zaouia, M., Tabard, A., and Lavou

´

e, E. (2020). Emodash:

A dashboard supporting retrospective awareness of

emotions in online learning. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies, 139:102411.

Florian-Gaviria, B., Glahn, C., and Gesa, R. F. (2013). A

software suite for efficient use of the european qualifi-

cations framework in online and blended courses. IEEE

Transactions on Learning Technologies, 6(3):283–296.

Govaerts, S., Verbert, K., and Duval, E. (2011). Evaluating

the student activity meter: Two case studies. In Ad-

vances in Web-Based Learning - ICWL 2011, pages

188–197. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Greiffenhagen, C. (2011). Making rounds: The routine work

of the teacher during collaborative learning with com-

puters. International Journal of Computer-Supported

Collaborative Learning, 7(1):11–42.

Groba, A. R., Barreiros, B. V., Lama, M., Gewerc, A., and

Mucientes, M. (2014). Using a learning analytics tool

for evaluation in self-regulated learning. In 2014 IEEE

Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) Proceedings,

pages 1–8. IEEE.

Hattie, J. and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback.

Review of educational research, 77(1):81–112.

Holstein, K., McLaren, B. M., and Aleven, V. (2018). Stu-

dent learning benefits of a mixed-reality teacher aware-

ness tool in AI-enhanced classrooms. In Lecture Notes

in Computer Science, pages 154–168. Springer Inter-

national Publishing.

Kitto, K., Cross, S., Waters, Z., and Lupton, M. (2015).

Learning analytics beyond the lms: the connected

learning analytics toolkit. In Proceedings of the Fifth

International Conference on Learning Analytics And

Knowledge, pages 11–15. ACM.

Martinez-Maldonado, R., Clayphan, A., Yacef, K., and Kay,

J. (2015). Mtfeedback: Providing notifications to en-

hance teacher awareness of small group work in the

classroom. Learning Technologies, IEEE Transactions

on, 8:187–200.

Mazza, R. and Dimitrova, V. (2007). CourseVis: A graphical

student monitoring tool for supporting instructors in

web-based distance courses. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies, 65(2):125–139.

McDonald, N., Schoenebeck, S., and Forte, A. (2019). Reli-

ability and inter-rater reliability in qualitative research:

Norms and guidelines for cscw and hci practice. Proc.

ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact., 3(CSCW):72:1–72:23.

Michel, C., Lavou

´

e, E., George, S., and Ji, M. (2017). Sup-

porting awareness and self-regulation in project-based

learning through personalized dashboards. 9(2/3):204–

226.

Molenaar, I. and van Campen, C. K. (2017). Teacher

dashboards in practice: Usage and impact. In Data

Driven Approaches in Digital Education, pages 125–

138. Springer International Publishing.

Mottus, A., Kinshuk, Graf, S., and Chen, N.-S. (2014). Use

of dashboards and visualization techniques to support

teacher decision making. In Ubiquitous Learning Envi-

ronments and Technologies, pages 181–199. Springer

Berlin Heidelberg.

Sarikaya, A., Gleicher, M., and Szafir, D. A. (2018). Design

factors for summary visualization in visual analytics.

Computer Graphics Forum, 37(3):145–156.

Schwendimann, B. A., Rodriguez-Triana, M. J., Vozniuk,

A., Prieto, L. P., Boroujeni, M. S., Holzer, A., Gillet,

D., and Dillenbourg, P. (2017). Perceiving learning

at a glance: A systematic literature review of learning

dashboard research. IEEE Transactions on Learning

Technologies, 10(1):30–41.

Sedlmair, M., Meyer, M., and Munzner, T. (2012). Design

study methodology: Reflections from the trenches and

the stacks. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and

Computer Graphics, 18(12):2431–2440.

Shneiderman, B. (2003). The eyes have it: A task by data

type taxonomy for information visualizations. In The

Craft of Information Visualization, pages 364–371. El-

sevier.

Shute, V. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of

Educational Research, 78:153–189.

Siemens, G. and Baker, R. S. (2012). Learning analytics and

educational data mining. In Proceedings of the 2nd

International Conference on Learning Analytics and

Knowledge - LAK '12. ACM Press.

Technavio (2016). Digital classroom market will grow at an

impressive cagr of almost 13% until 2020.

Verbert, K., Govaerts, S., Duval, E., Santos, J. L., Van Ass-

che, F., Parra, G., and Klerkx, J. (2014). Learning

dashboards: an overview and future research opportuni-

ties. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 18(6):1499–

1514.

Xhakaj, F., Aleven, V., and McLaren, B. M. (2017). Effects

of a dashboard for an intelligent tutoring system on

teacher knowledge, lesson plans and class sessions. In

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 582–585.

Springer International Publishing.

Yuan, S., Tabard, A., and Mackay, W. (2008). Streamliner:

A general-purpose interactive course-visualization tool.

In 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Knowledge

Acquisition and Modeling Workshop, pages 915–919.

Zapata-Rivera, D. and Katz, I. (2014). Keeping your audi-

ence in mind: applying audience analysis to the design

of interactive score reports. Assessment in Education

Principles Policy and Practice, 21.

PROGDASH: Lessons Learned from a Learning Dashboard In-the-wild

117