Overcoming Barriers for OER Adoption in Higher Education

Application to Computer Science Curricula

Rosa Navarrete and Diana Martinez-Mosquera

Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Department of Informatics and Computer Science, Ecuador

Keywords: Open Educational Resources, OER-based Learning, Higher Education, Computer Science, Community of

Practice, MERLOT.

Abstract: The use of Open Educational Resources (OER) in all contexts of education is increasingly promising.

Nevertheless, some barriers are discouraging or delaying the adoption of OER in Higher Education (HE). In

this work, we propose a strategy to overcome obstacles that hinder the adoption of OER as teaching materials

in Computer Science Curricula. This strategy is based on the collaborative work of professors and students

within a Community of Practice (CoP) backed up by MERLOT, a renowned repository of OER. To validate

the proposed strategy, we applied it in some courses of the Computer Science Engineering Curricula from a

Latin American university by two consecutive academic terms. The evaluation obtained from professors and

students who participated in this teaching-learning experience was encouraging for the use of OER. It also

enabled us to settle issues concerning the discoverability and quality of OER. Furthermore, the results of this

proof fostered the institutional willingness to sponsor and spread the OER adoption initiative.

1 INTRODUCTION

Open Educational Resources (OER) are freely

accessible digital materials that are intended to use in

education. A conjunction of factors is driving OER as

a strategy to increase access to educational

opportunities globally. As evidence of that, the

UNESCO Recommendation on OER, adopted in

November 2019, proclaims the use of OER as a

change agent to ensure inclusive and equitable quality

education for all (UNESCO, 2019).

Currently, higher education (HE) takes advantage

of technology-based resources, such as OER, to low

costs and broaden their capacity to serve the growing

demand (Atherton, et al., 2016).

The advantages of using OER in HE have been

documented in some works. For example, the use of

open textbooks is exposed in (Jhangiani, et al., 2016;

Ruth & Boyd, 2016; Ozdemir & Hendricks, 2017),

the use of OER in undergraduate courses is addressed

in (Bradshaw , et al., 2013; Klein, 2015).

Nevertheless, in spite of the increasing

mainstreaming of OER in HE, the obstacles for their

formal adoption are still unsolved (Wong & Li,

2019). In this work, we propose a strategy that aims

to overcome some barriers to OER adoption in HE

curricula. This strategy is based on the shared

knowledge in communities of practice (CoP)

integrated by educators and students.

To validate this strategy, we applied it in some

courses of Computer Science Engineering from a

public university in a Latin American country. We

aim to test the feasibility of OER-based teaching in

formal education when the content of knowledge

discipline is aligned with the ACM/IEEE Computer

Science Curricula (2013).

The results of this proof have shown that both

professors and students achieved a fulfilling

experience of teaching-learning. Professors

highlighted the quality and diversity of resources, as

well as the interrelations that arise from their

participation within a CoP, which provide them for

new academic horizons. The students found that they

are capable of learning from courses prepared by

academics from leading universities of developed

countries.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 covers the background concepts, Section 3

depicts the strategy for the adoption of OER, Section

4 describes the results of the application of the

proposed strategy, and Section 5 presents the

conclusions and future work.

Navarrete, R. and Martinez-Mosquera, D.

Overcoming Barriers for OER Adoption in Higher Education Application to Computer Science Curricula.

DOI: 10.5220/0009471205590566

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 1, pages 559-566

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

559

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Open Educational Resources

The latest definition of OER states: “OER are

teaching, learning and research materials that reside

in the public domain or have been released under an

open license that permits no-cost access, use,

adaptation and redistribution by others with no or

limited restrictions” (UNESCO, 2019). OER range

from full courses including syllabi to textbooks,

lecture notes, video lectures, software simulations,

and more (Atkins, et al., 2007).

OER are mostly released with a Creative

Commons (CC) license. For the fully comply of the

concept of “openness”, resources should enable the

5R activities (Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix,

Redistribute (Wiley & Hilton, 2018).

Many of the largest OER websites are supported

by prestige Universities or academic coalitions, such

as OER Commons by ISKME (Institute for the Study

of Knowledge Management in Education), MERLOT

by the California State University Center for

Distributed Learning, and the OpenLearn project at

the Open University of the United Kingdom,

OpenStax College.

2.2 Community of Practice

The term Community of Practice (CoP) refers to a

group of people who agree to participate in

collaborations that take place in relation to a domain

of knowledge, developing shared practices to build a

common store of knowledge and accumulate

expertise in the area (Wenger & Snyder, 2000).

To differentiate from any community, a CoP must

have three characteristics (Wenger, 2011).

a. The domain. Members are connected by a

learning purpose they share. Therefore,

membership implies to hold a competence over

the domain and an interest in deepening

knowledge on it.

b. The community. Members are engaged in joint

activities, help each other, and share knowledge

and information. In pursuing their interest in their

domain, they build collaborative relationships.

c. The practice. Members develop a shared set of

practices, resources, tools, and documented

experiences to address problems in the domain.

Currently, CoPs are emerging as a strategy in the

educational field to promote knowledge sharing.

Members develop their willingness to share useful

resources and support other members to increase their

domain of knowledge (Tseng & Kuo, 2014).

3 ADOPTION OF OER IN HE

3.1 Barriers for Adoption

The obstacles to the adoption of OER into HE have

been documented in the literature. A survey applied

to 2,144 higher education professors in the U.S.

(Allen & Seaman, 2014), revealed that the time and

effort required to find, retrieve, evaluate and adapt

OER was the most significant barrier for OER

adoption. In a follow-up survey (Seaman & Seaman,

2017), applied to 2,700 professors, the main obstacle

continued to be this same, the effort needed to find

and evaluate suitable resources. Also, in a

complementary qualitative study conducted with 218

professors, the lack of time for resources evaluation

became the barrier for OER adoption (Belikov &

Bodily, 2016).

Another study (Kortemeyer, 2013) exposed that

OER adoption major hurdles were discoverability

(searching and retrieve suitable resources) and quality

control. Moreover, the Commonwealth of Learning

(COL) and UNESCO conducted six regional

consultations, where the main barrier to

mainstreaming OER was described as the lack of

users’ capacity to access, reuse and share OER (COL,

2017).

On the other hand, the adoption of OER in Latin

American HE introduces the obstacle of the language

of the resources, because the predominant language

for OER is English.

The quality of OER has widely covered in

literature as a primary requisite to encourage their use

in HE. For Camilleri, et al. (2014), the quality

assurance of OER relies on peer work, from the

perspective of its fitness for the required purpose, the

ability for reuse (editing), and the kind of learning

experience that can provide.

Another alternative is the application of rubrics to

evaluate the quality of OER. Although rubrics aim to

measure OER quality, each one emphasizes different

aspects. For instance, the rubric used by OER

Commons includes the degree of alignment to

standards, quality of explanation of the subject

matter, the assurance of accessibility, and some other

aspects depending on the type of resource (Achieve,

2011). Some other rubrics relies on the content

quality as a major dimension for evaluating OER

quality, considering indicators such as completeness,

clarity, and accuracy (Jonsson & Svingby., 2007).

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

560

In this work, we assumed as a starting point that

professors already have awareness about the nature

and purpose of OER. We have focused our strategy

on those barriers that are possible to overcome with

actions conducted by professors themselves. For this

reason, the institutional policy for supporting OER

adoption is out of the scope of the proposed strategy.

The barriers we address are those considered as the

most significant according to previously cited works:

a. Discoverability. It involves the search and

retrieval of OER that fit the content and

pedagogical requirements of the subject taught.

b. Quality. It includes these attributes of OER: the

relevance, accuracy, updated information, and

appropriate format for learning purpose.

c. Language. The language used to present the

content of OER.

3.2 Strategy to Overcome Barriers

The strategy description and the rationalizing of how

its application can surpass the barriers for adoption

are explained follow.

3.2.1 Description of the Strategy

The strategy is based on the participation of

professors in a CoP offered by MERLOT under the

denomination of “Community Portals” (Tovar, et al.,

2017). At present, MERLOT holds some CoP aligned

with different disciplines where educators and

students can seek, utilize, curate, review, and rate

learning resources that have been included. These

CoPs are maintained by a discipline Editor and a

related editorial board of peer reviewers who ensure

the quality of the OER by reviewing their pertaining

to the discipline, the correctness of their content, and

their usefulness for teaching and learning.

In 2016, MERLOT created CoPs based on OER

utilization in two knowledge areas concerning the

interest of our proposal.

a. Information Systems and Information

Technology (IT/IS).

b. Computer Science (CS).

These CoPs are related to the knowledge areas

aligned with the undergraduate course topics

recommended by the Accreditation Board for

Engineering and Technology (ABET) for

accreditation of degree programs in computer

science, information systems, software engineering,

information technology, and cybersecurity. In the

case of Computer Science, the curricula

recommendation is guided by (ACM/IEEE, 2013).

Table 1 shows the Computer Science taxonomy of

Knowledge Areas, according to ACM/IEE, with their

acronym and name.

To prove the proposed strategy, it was applied in

two consecutive academic terms (September 2018 –

February 2019, March 2019 – August 2019),

considering two subjects of the current curricula,

“Fundamentals of Databases," that is included in the

IM knowledge area, and “Operating Systems,” that is

included in the OS knowledge area.

Table 1 also exhibits the number of resources

available through the MERLOT CoP in CS

knowledge areas at the beginning and the end of the

application of the strategy. The increasing of the

available OER will be analysed later in this

document.

The participants in the application of the strategy

were the group of students enrolled in each academic

term for the mentioned subjects and, the respective

professors. While the group of students was different,

the professors stayed assigned for the subject in both

terms.

Furthermore, a recommendation in this strategy is

the creation of a Course ePortfolio in MERLOT to

include OER, that have been previously selected,

within a Bookmark Collection and create the syllabus

information of the course.

3.2.2 How Strategy Overcomes Barriers

The strategy proposed in this work enabled to

overcome the barriers to the adoption of OER

mentioned in section 3.1.

a. Discoverability. The professor, member of the

CoP, in the CS discipline, has access to a

collection of OER previously approved by the

Editor and by the peer review. This fact simplifies

discoverability issues, enabling the professor to

save time and effort.

b. Quality. The two-fold review process of OER

carried out by the Editor and academic peers

contributes to ensuring the quality of the

resources. Further, the provenance of OER is

considered an indicator of quality. Mostly

resources collected, particularly in CS discipline,

have been produced by professors of outstanding

universities in the world.

c. Language. All collected resources for CS are

available only in the English language. It does not

represent an actual barrier in the CS domain

because English is considered the lingua franca of

Computing and students are competent to use it.

Overcoming Barriers for OER Adoption in Higher Education Application to Computer Science Curricula

561

Table 1: CS Taxonomy in CoP and number of resources.

Knowledge

Area

Acronym

Knowledge Area Name

Number of

resources

Aug.

2018

Aug.

2019

AL Algorithms and Complexity 45 48

AR

Architecture and

Organization

22 25

CS Computational Science 22 46

DS Discrete Structures 22 28

GV Graphics and Visualization 11 13

HCI Human-Computer Interaction 139 142

IAS

Information Assurance and

Security

25 28

IM Information Management 165 177

IS Intelligent Systems 402 407

NC

Networking and

Communications

173 959

OS Operating Systems 27 28

PBD Platform-based development 11 11

PD

Parallel and Distributed

Computing

7 7

PL

Parallel and Distributed

Computing

4074 4621

SDF

Software Development

Fundamentals

44 53

SE Software Engineering 48 56

SP

Social Issues and

Professional Practice

16 18

4 RESULTS OF THE STRATEGY

APPLIED

The proposed strategy for OER adoption requires that

the professor develop these steps:

a. Get membership in MERLOT by completing the

Sign-up form of the Web page.

b. Select the Academic Discipline Portals in the

Community Portals. Choose the Computer

Science discipline.

c. Create a Bookmark collection. This step requires

to select the OER they consider appropriate to

support the topics in the syllabus of the subject,

from the resources collection within the

discipline.

d. Create a Course ePortfolio with OER included in

the Bookmark collection. This step requires to

complete the information about syllabus subject

(topics, prerequisites, pedagogical approach,

learning outcomes, and assessment).

e. Request

students to become MERLOT members

and select the Computer Science Community

Portal to grant them access to the Course

ePortfolio just created.

As a way of example, some screen captures of the

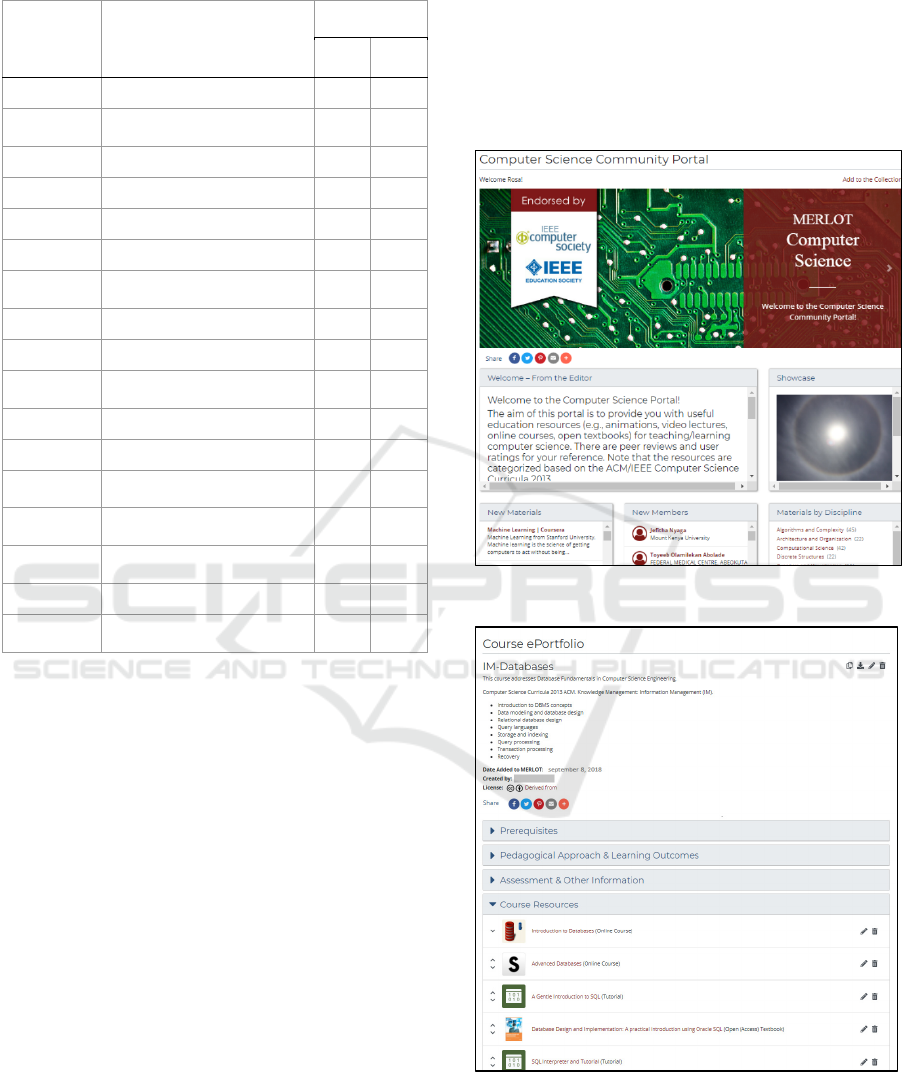

steps described are presented. Figure 1 shows a screen

capture of the MERLOT Computer Science

Community Portal.

Figure 1: MERLOT Computer Science Community Portal.

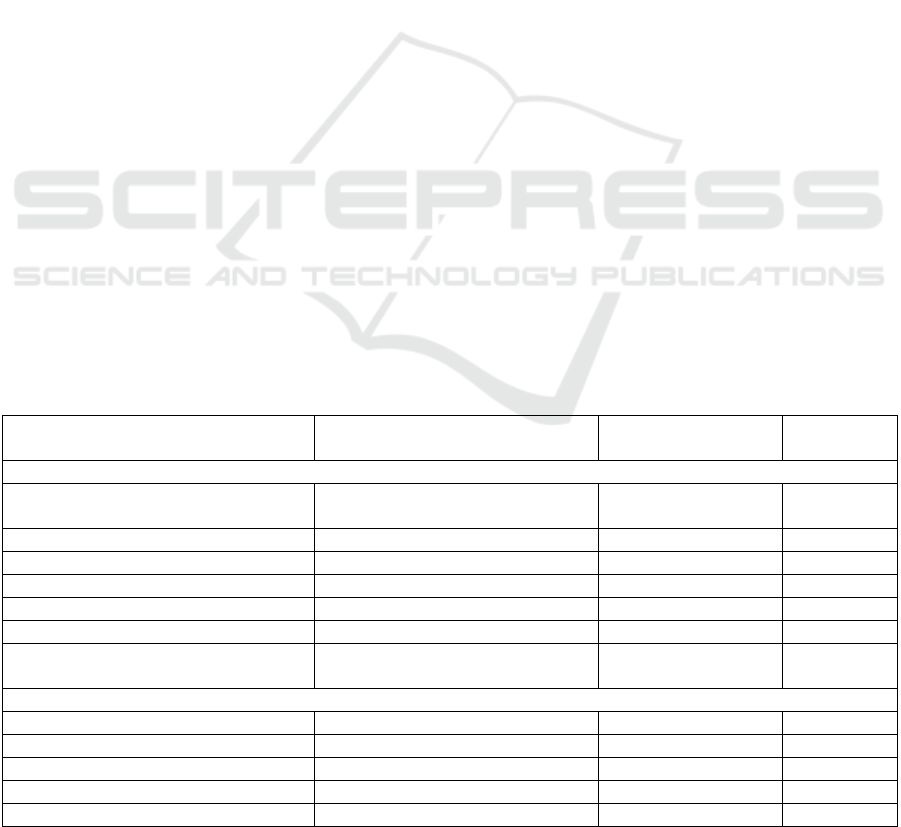

Figure 2: ePortfolio for Fundamentals of Databases.

Figure 2 shows a screen capture of the Course

ePortfolio named IM-Databases, which have been

created by the professor for the Fundamentals of

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

562

Databases subject. Only a partial list of selected

resources is displayed in the image.

For each subject involved in this proof,

“Fundamentals of Database” and “Operating

System”, a sample of OER selected for the Course

ePortfolio is summarized in Table 2.

4.1 Professors Evaluation

The observations expressed by professors concerning

the development of this proof of the strategy are

mentioned. These were the positive comments:

a. The variety and academic rigor of OER.

Professors found educational resources in

multiple formats to cover their teaching purposes.

They appreciated the advantages of simulation

software for learning since students can explore,

experiment, and model real situations. They

awarded that the creation of this kind of resources

involves high production costs, so it was valuable

to get them for free.

b. The right categorization taxonomy for OER used

in CS simplified the search issues. Nevertheless,

it was important to invest time to select the

appropriates resources.

c. The interrelations promoted in the CoP.

Professors gained expertise in their field. It has

aroused their interest to participate more actively

as reviewers and contributors of resources.

These were the negative and neutral comments:

a. The different approach of OER. Professors

affirmed that it is tough to comply with the

syllabus using OER (approximately 45% could be

covered). It is because there were differences in

approaching the topics of the syllabus.

b. The time to prepare the teaching based on using

OER is not profitable for the first time. Professors

agreed in the effort demanded to apply OER in

their subjects, for the first time. Nevertheless, in

the next academic term, when they taught the

subject again, the effort was considerably lesser.

c. The use of OER in teaching is feasible for those

who have expertise in the subject. Professors

claimed that it is not an advisable teaching

strategy for a professor who is a novice teaching

the subject.

d. The lack of metadata for OER. Professors

observed that resources' metadata included in the

informative web page displayed in MERLOT

were incomplete. Notably, the lack of license

associated with the publication of the resource

was missing. It would expect they have a Creative

Commons license.

4.2 Students Evaluation

The proof of the strategy involved 56 students of

Fundamentals of Databases courses and 46 students

of Operating Systems courses, considering both

academic terms. No student took both subjects at time

because these are at different levels in the curricula.

In total, 102 students participated in this experience.

Because of the lack of space, the results of the

evaluation by students are presented for the total of

students.

In this work, the evaluation of the acceptance of

the use of OER by students had a qualitative

Table 2: Sample of the selected resources for Course ePortfolio.

Name Provenance Type Include tests

/exams

SUBJECT: DATABASE FUNDAMENTALS – ePortfolio IM-Databases

Introduction to Databases University of Stanford, US Online Course (Video

lectures)

Yes

Advanced Databases The Saylor Foundation, US Online Course Yes

A Gentle Introduction to SQL Napler University, UK Online Tutorial Yes

SQL Interpreter and Tutorial University of Washington, US Online Tutorial

Introduction to Modern Database Systems The Saylor Foundation, US Online Course Yes

SQL Tutorial W3C School Online Course Yes

Database Design and Implementation: A

practical introduction using Oracle SQL

Oracle CIO Open Access Textbook Yes

SUBJECT: INTRODUCTION TO OPERATING SYSTEMS – ePortfolio OS-IntroOS

Animations for Operating Systems University of Virginia, US Animations No

CPU-OS Simulator Edge Hill University, UK Software application No

Operating Systems and System Programming University of California, Berkeley, US Video lectures No

Computer Structures and Operating Systems University of Münster, Germany Presentations Yes

Operating Systems and Middleware California State University, US Open Access Textbook Yes

Overcoming Barriers for OER Adoption in Higher Education Application to Computer Science Curricula

563

Table 3: Questionnaire for students’ evaluation.

Program: Use of OER in courses of Computer Engineering

Name of the course: Fundamentals of Databases / Operating ¨Systems

Academic Term: 2018-B (September 2018 – February 2019)

Questionnaire of opinion: Please, answer each question by checking the box that best describes your perception.

Q1. How was your knowledge on OER

b

efore taking the course? Excellen

t

Fairy Goo

d

Moderate None

Q2. How was your knowledge on CoP before taking the course?

Excellent Fairy Good Moderate None

Q3. How do you value the achievement of learning outcomes with

the use of OER?

Excellent Fairy Good Moderate None

Q4. How do you value the use of learning resources published by

prestigious Universities?

Excellent Fairy Good Moderate None

Q5. How do you value your membership in MERLOT CoP for

Computer Science?

Excellent Fairy Good Moderate None

Response freely about these questions:

Q6. Did you obtain benefits from learning by using OER?

Q7. Did you perceive obstacles in this learning experience

b

y using OER?

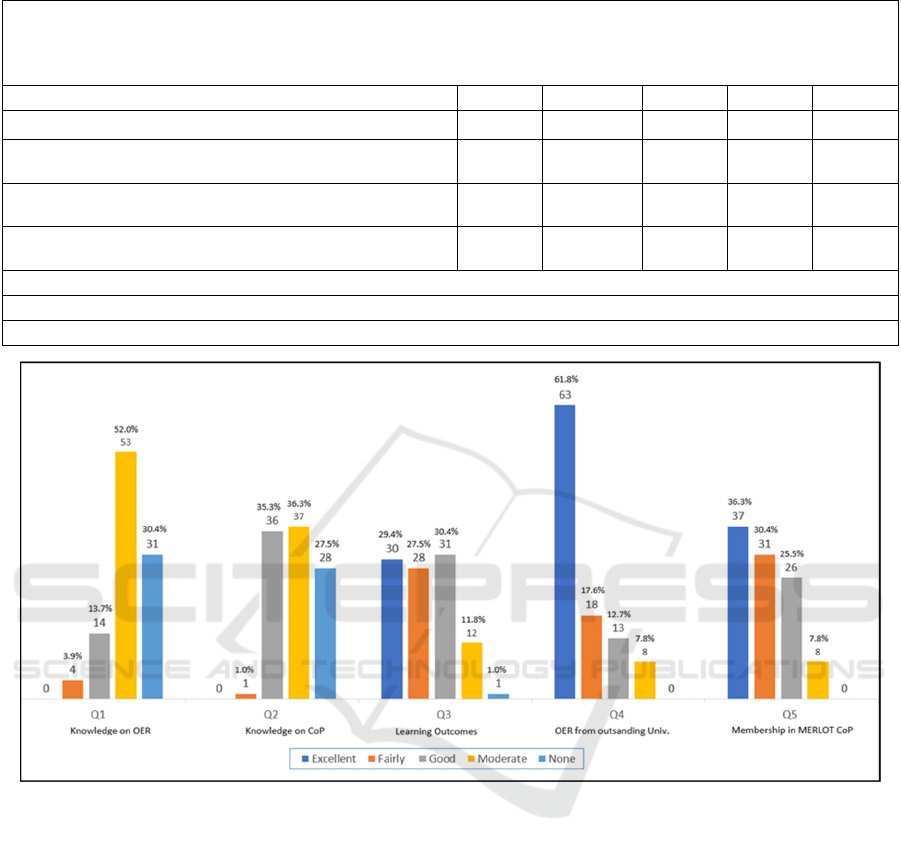

Figure 3: Results of questionnaire.

approach. To evaluate the rate of acceptance of OER

in the learning process, students were evaluated

through a Goal, question, metric (GQM) approach

(Koziolek, 2008) by using a Likert scale.

The questionnaire was applied at the end of each

academic term to all students involved in this proof of

the strategy. The questionnaire content is presented in

Table 3. It embraced three groups of questions:

G1. Two closed questions (Q1 and Q2) to explore

the initial level of knowledge that the student had

about the OER and CoPs.

G2. Three closed questions (Q3, Q4, and Q5) to

know the students’ appreciation concerning this

learning experience.

G3. Two open questions (Q6 and Q7) to receive

feedback

from

students

about

the

use

of

OER

in

the

learning process.

All results for G1 and G2 (closed questions) are

presented in Figure 3, a grouped bar chart. Each group

of bars that represent a question is labelled with a

descriptive text. For each question, a bar in different

colour represents the number of responses (and the

respective percentage) for each level of appreciation.

The total number of students answered the

questionnaire, it means 102 responses.

For closed questions in G1 (Q1 and Q2).

Considering the sum of responses obtained for

"Knowledge", in the scale good and moderate, it is

observed that students were less informed about the

OER concept (65.7%) than about the CoP concept

(71.6%).

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

564

Nevertheless, around 30% of students did not

have any knowledge about those terms. It is

worthwhile to remark that students have not

participated in CoP until this experience despite the

importance of teamwork in the computer science

professional activities.

Concerning Q3, it is observed that students have a

positive opinion on the learning outcomes achieved

through this experience of the use of OER. The

highest percentages correspond to excellent (29.4%),

fairly (27.5%), and good (30.4%) appreciations.

In Q4, students' responses show a remarkable

valuation for the use of OER published by prestigious

universities (61.8%), and 30.4% have a positive

opinion (fairly and good).

For Q5, students also recognized the value of

participation in the MERLOT CoP. The excellent,

fairly and good appreciations represent 92.2% of

responses.

For open questions in G3 (Q5 and Q6) the aspects

noted below have been pointed out by most students.

Concerning the benefits of using OER, in Q6,

students highlighted that the learning based on OER

prepared in prestigious universities added value to

their education. It became a worthwhile experience

for them. Students also recognized that simulations

and online courses as valuable materials to enhance

their learning.

Concerning the obstacles of using OER, in Q7,

students mentioned that the language was a barrier for

comprehension of the content of the resources.

However, they were aware that the domain of the

English language is a key competency for their career

and, consequently, they were gratified to surpass the

challenge of the language in their learning. Students

did not identify additional barriers.

It is important to mention that the summative

evaluations of students in the subjects of this proof of

the strategy, did not show variance respect previous

academic terms. All students approved the courses.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this proof of the strategy, we have tested its

efficacy to surpass the most recognized barriers for

the adoption of OER in HE, as part of subjects in the

curriculum of Computer Science Engineering.

The novelty of this strategy was the introduction

of a CoP that supports the tasks of discovery and

quality control of OER, which be reused as learning

materials in the subjects of the curricula.

Therefore, we aimed to engage professors and

students, within a CoP where they could interact with

other members grouped by the same academic

interest. In this case, we joined to the MERLOT

Community Portal for Computer Science discipline.

The taxonomy applied to classify the resources

aligned with the (ACM/IEEE, 2013), provided a

helpful base to select the appropriate OER for the

subject that the professor needs. In this way, some

barriers, as the discoverability and quality of

resources, could be surpassed.

Professors and students positively evaluated the

proposed strategy. Professors remarked that the

participation of students in the CoP and the use of

OER motivated students for self-learning,

encouraging their critical and reflective thinking

Students recognized the attainment of learning

outcomes and shown their enthusiasm to participate

in the MERLOT CoP for enlarging their relations

with other academic actors of foreign Universities.

The participation in this strategy for OER-based

learning has persuaded to professors and students to

advocate the OER adoption. Hence, they can boost

the spreading of this strategy to include most of the

subjects of the curricula.

Arguably, OER-based education has a significant

chance of success if it provides a trustworthy,

ongoing assessment of the student's work. That is the

professor's role. Moreover, once professors embrace

OER as a valid alternative to the preparation of their

materials, or the payment for textbooks, the learning

in HE could be improved. For instance, professors

will have more time to dedicate it to other research

activities. Also, students will be more independent to

face their learning, able to deep in their interests,

creativity, and responsibility will increase, and,

working in a collaborative group within a CoP, they

will experiment the value of sharing knowledge.

On the other hand, it is necessary to mention that,

as shown in Table 1, the number of OER in the

knowledge areas concerning this CoP increased in a

year, but not in a significative number. Nevertheless,

this increase was extraordinary for Networking and

Communication (from 173 to 959 learning resources).

The results of this proof of the strategy have been

a positive impact on the institutional willingness for

OER sponsorship. The academic authorities have

decided to involve new subjects in the application of

this strategy for the next academic term. Therefore,

we can conclude positively about the success of the

strategy.

The transformative potential of OERs would be

very advantageous for public universities to promote

the affordability of knowledge for more people.

Overcoming Barriers for OER Adoption in Higher Education Application to Computer Science Curricula

565

REFERENCES

Achieve, 2011. Rubrics for evaluating open education

resource (OER) Objects. [Online] Available at:

https://www.achieve.org/achieve-oer-rubrics

ACM/IEEE, 2013. Computer Science Curricula 2013.

United States of America: Association for Computing

Machinery (ACM) and IEEE Computer Society.

Allen , I. E. & Seaman, J., 2014. Opening the curriculum:

Open educational resources in U.S. higher education,

Massachusetts, US: Pearson.

Atherton, G., Dumangane, C. & Whitty, G., 2016. Charting

equity in higher education: drawing the global access

map, London, UK: Pearson

Atkins, D., Seely Brown, J. & Hammond , A. L., 2007. A

review of the Open Educational Resources (OER)

Movement: Achievements, Challenges and New

Opportunities. San Francisco, CA, US: The William

and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Belikov , O. M. & Bodily, R., 2016. Incentives and barriers

to OER adoption: A qualitative analysis of faculty

perceptions. Open Praxis, 8(3), pp. 235-246.

Bradshaw , P., Younie, S. & Jones, S., 2013. Open

Education Resources and Higher Education Academic

Practice, 30(3), 186-193. Retrieved January 5, 2020

from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/132849/.

Campus-Wide Information Systems, 30(3), pp. 186-193.

Camilleri, A. F., Ehlers, U. D. & Pawlowski, J., 2014. State

of the Art Review of Quality Issues related to Open

Educational Resources (OER). JCR Scientific and

Policy Report, pp. 2-43.

COL, 2017. Open Educational Resources: Global Report

2017, Burnaby, British Columbia: s.n.

Jhangiani, R. et al., 2016. Exploring faculty use of open

educational resources at British Columbia

postsecondary institutions, Victoria, BC: BCcampus.

Jonsson, A. & Svingby., G., 2007. The use of scoring

rubrics: Reliability, validity and educational

consequences. Educational Research Review, 2(2), pp.

130-144.

Klein, G., 2015. Embedded digital resources are in,

traditional text out at UMUC, Maryland, US: WCET

Frontier.

Kortemeyer, G., 2013. Ten Years Later: Why Open

Educational Resources Have Not Noticeably Affected

Higher Education, and Why We Should Care.

EDUCAUSE Review Online.

Koziolek, H., 2008. Goal, Question, Metric. Dependability

Metrics: Advanced Lectures, pp. 39-42.

Ozdemir, O. & Hendricks, C., 2017. Instructor and student

experiences with open textbooks, from the California

open online library for education (Cool4Ed). Journal of

Computing in Higher Education, 29(1), pp. 98-113.

Ruth, D. & Boyd, J., 2016. OpenStax already saved

students $39 million this academic year , s.l.: s.n.

Seaman, J. E. & Seaman, J., 2017. Opening the Textbook:

Educational Resources in U.S. Higher Education, s.l.:

Pearson.

Tovar, E., Chan, H. & Reisman, S., 2017. Promoting

MERLOT Communities Based on OERs in Computer

Science and Information Systems. s.l., s.n., pp. 700-706.

Tseng, F.-C. & Kuo, F.-Y., 2014. A study of social

participation and knowledge sharing in the teachers'

online professional community of practice.

Computers

& Education, Volume 72, pp. 37-47.

UNESCO, 2019. UNESCO Recommendation on Open

Educational Resources (OER). [Online] Available at:

https://en.unesco.org/news/unesco-recommendation-

open-educational-resources-oer [Accessed December

2019].

Wenger , E. & Snyder, W., 2000. Communities of practice:

the organizational frontier. Harvard Business Review,

76(1), pp. 139-146.

Wenger, E., 2011. Communities of Practice: A brief

introduction. STEP Leadership Workshop, University

of Oregon, Volume 6.

Wiley, D. & Hilton, J., 2018. Defining OER-Enabled

Pedagogy. The International Review of Research in

Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4).

Wong, B. & Li, K., 2019. Using Open Educational

Resources for Teaching in Higher Education: A Review

of Case Studies. s.l., s.n.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

566