The Economic Impact of Intellectual Property Management:

Towards Model of Intellectual Property Management

Tomasz Sierotowicz

a

Jagiellonian University, Faculty of Management and Social Communication,

Institute of Economics, Finance and Management, Department of Economics and Innovation,

Prof. Lojasiewicza 4, 30-348, Krakow, Poland

tsierotowicz@uj.edu.pl

Keywords: Management of Intellectual Capital, IT Management, Model of the Intellectual Property Management,

Empirical Analysis.

Abstract: Subject literature indicates the International Business Machines (IBM) as the uninterrupted leader in the

number of patents obtained from United States Patents and Trademarks Office (USPTO), out of all enterprises

and industries for over 25 years. Since 1998, the IBM has conducted an internal business segment called

Intellectual Property Management (IPM). This article presents results of two research goals of this study. The

result of the first goal was to create an original design of the IPM model based on the IBM business experience.

Given the interdependent environment of IBM, the complexity theory approach was used to achieve this goal.

The second goal was to evaluate the economic profitability of activities included in the IPM segment, and

their impact on the total income of the whole IBM enterprise, over the entire research period 1998-2018. The

created design of IPM segment is a new and significant help for managers dealing with the complex issues of

intellectual property, which allows to achieve economic profitability of IPM in the large enterprises. The final

conclusion of results of the second goal indicated that out of all IPM activities only custom development of

intellectual property was the only driver of profit increase in the IBM.

1 INTRODUCTION

The evaluation of research and development (R&D)

expenditure efficiency in relation to the number of

obtained patents is economically significant. This

evaluation addresses how enterprises manage their

spending in a profitable way; by reducing the cost of

a single obtained patent while increasing the number

of obtained patents in the long-term. One of the best

ways to evaluate R&D expenditure efficiency is to

undertake research on leading enterprises in terms of

the number of obtained patents. Previous research

indicates that, over the last three decades, enterprises

belonging to the Information and Communication

Technologies (ICT) sector obtained the highest

number of patents from the USPTO compared to

other industries and enterprises (USPTO, 2019).

Among them, the International Business Machines

(IBM) was the uninterrupted leader in the number of

obtained patents from the for over 27 years (USPTO,

2019; IBM, 2017). Source documentation, made up

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1462-8267

of annual reports also confirms this statement

(Sierotowicz, 2017). Previous research also indicated

that during 1997-2015, IBM maintained the flattest

value of R&D expenditure, while the number of

patents obtained from the USPTO was the highest

(Sierotowicz, 2017). In addition, the number of

patents obtained per US$1 million spent on R&D was

the highest and increased annually by an average of

7.92% (Sierotowicz, 2017). This indicates that every

dollar spent on R&D at IBM resulted in a better

outcome measured in the obtained patents, ensuing

cheaper patents. However, this research dedicated to

patent activity also reveals that IBM conducted an

internal business segment called Intellectual Property

Management (IPM), closely related to other business

segments including R&D. Since 1998, this business

segment has been recognised in source

documentation. According to these documents, the

IPM segments is dedicated to managing all types of

the intellectual property in IBM, including patent

activity (IBM, 2019; USSEC, 2019). The findings

Sierotowicz, T.

The Economic Impact of Intellectual Property Management: Towards Model of Intellectual Property Management.

DOI: 10.5220/0009513600730081

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE 2020) - Volume 3: ICE-B, pages 73-81

ISBN: 978-989-758-447-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

73

presented above are the most important reasons

behind launching another research effort, this time

dedicated to a more in-depth understanding of how

this enterprise managed the intellectual property, as

well as economic profitability over a long-time

period. The main goals of this article are: to present

the results of the research that is a conceptual design

and implementation of the IPM segment in the

corporate complex environment and economic

achievements of this segment, generates as a part of

entire income. The research period covers all years

since the IPM segment was indicated in the source

documentation, from 1998 to 2018. The presented

case study indicates how the unquestionable leader of

patent activity designed and configured the IPM

segment with other segments like production, R&D,

acquisitions and divestitures, and addresses whether

the IPM segment generates economic profit over the

entire research period.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

The measurement of patent activities as economic

indicators, particularly the relationship between the

number of patents and expenditure on R&D activities,

is not a new concept (Schmookler, 1951; Stoneman,

1987; Meliciani, 2000; Lanjouw and Schankerman,

2004; Arora et al. 2010). Analyses and evaluations

presented in existing literature covers the inventive

activities of countries, sectors and industries, such as

the ICT sector (Thornhill, 2006; Sierotowicz, 2015).

The conclusions of these studies indicate that there is

a strong relationship between expenditure on R&D

and inventive activities represented by the number of

obtained patents. Hence, patent activity as a suitable

measure of R&D spending is also widely discussed in

existing literature. There are mainly a few streams of

discussion related to the patent activity, where

specific arguments are presented, for example: usage

of specific statistical tools, significance of patent

applications and granted patents (Baraldi et al. 2014),

or the lag between input and output variables of R&D

activities (Bjelland and Chaptman, 2008; Ness,

2012). Although these arguments are important, none

of them discredit patent activity as an adequate

measure of R&D. However, patent activity is a

component of intangible assets that belongs to the

intellectual property of an enterprise (Henkel et al.

2013; Hagedoorn and Zobel, 2015). Although patent

activity is not the only result of R&D, it is important

to recognise that it has many sources inside and

outside the enterprise environment beyond R&D,

including employees, acquisitions or custom

developed projects (Sagasti, 2004; Afauf, 2009;

Palfrey, 2011; IBM, 2013; Alimov and Officer,

2017). Existing literature presents research results in

relation to the sophisticated role of intellectual

property in business management (Junghans et al.

2006; Kianto et al. 2017). Other discussions are

related to the usage of intangible assets in business

strategy (Kaplan and Norton, 2004; Manzini and

Lazzarotti, 2016; Sessions and Hamaty, 2016) and the

evolution of the intellectual property role in the

enterprise (Holgersson et al. 2017). But widely

discussed in the literate problem related to successful

implementation of the IPM in the enterprise, is not

only sophisticated and it is impossible to describe it

through common components. Instead of the

sophisticated and reductionist approach that is

applied in many existing literature examples, the

complexity theory approach should be used

(Richardson, 2008; Espinosa and Walker, 2017).

Large enterprises representing unique and complex

environments. In the case of IBM, there are about 90

international wholly owned subsidiaries. In such

environment, design the IPM efficiently aligned with

all sources and products and services in order to

achieve advantage of opportunity to support the

generated income is the most important and complex

managerial issue. This article presents an example of

such a successful solution, based on the complexity

theory approach that combines the abovementioned

examples.

3 MATERIALS AND METHOD

This research consists of two stages. The first stage

was to provide a more in-depth understanding of how

IBM managed its intellectual property and intangible

assets. The intellectual property and intangible assets

are used in this research according to the rules

presented in the General Accepted Accounting

Principles (GAAP) and Statement of Financial

Accounting Standard (SFAS). As Hargadon and

Douglas (2001, p. 480) pointed out, “historical case

studies provide a perspective that covers the decades

often necessary to observe an innovation's emergence

and stabilization”, to achieve the main goal of this

article, a longitudinal case study approach was used.

The IPM evolved over time. Adopting a long-term

perspective helps to correctly specify the complex

role of IPM in business activities. This research

covers the period of 1998-2018, as the IPM segment

of IBM was included in source documentation from

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

74

1998. As stated in the introductory section of this

article, there are four reasons why IBM was chosen

for this study. Firstly, IBM is the uninterrupted leader

in the number of obtained patents from the USPTO,

among all enterprises, sectors and industries for over

27 years. Secondly, the results in patent activity was

achieved based on the increased efficiency of R&D

spending, not the amount of spending. Thirdly, the

patents obtained by IBM became cheaper. Finally,

IBM introduced its new IPM segment where patent

activity is one of many other activities related to

intellectual property and intangible assets. Given the

complex and interdependent environment of IBM, to

achieve the research goals of this study, it was

necessary to abandon the sophisticated and

reductionists approach, as presented in many existing

literature examples, and apply the complexity theory

approach (Espinosa and Walker, 2017; Richardson,

2008). The design of IPM, efficiently aligned with all

sources of intangible assets (inputs) and products and

services of enterprise (outputs), to successfully

support the generated profit, become the most

complex managerial issue.

The second stage of this research was to analyse and

evaluate the dynamics of the economic profitability

of the IPM segment, its impact on the total income of

the whole IBM enterprise, over the specified research

period. This stage consists of two steps. Firstly, to

analyse and evaluate the IPM segment separately to

identify whether it generates profit or loss. In this

case, the costs and revenues can be used as an input

and output variables, or at least total IPM income

before tax. Hence, the income before tax does not

include the analysis of cash flow; however, it

evaluates the economically important issue of

whether profits or losses are generated by the IPM

segment. Secondly, to analyse and evaluate the IPM

segment impact on the total income of the entire IBM,

before tax. This evaluation identifies the extent and

dynamic rate of the IPM segment impact on the total

income of the IBM, over the specified research

period. As the IPM segment operates continuously

over the research period, empirical analysis is used to

indicate the continuous impact of the IPM segment

(profits or losses, as well as dynamics) on the total

income of IBM, before tax, in both steps of the second

stage, over the research period. This approach ensures

that single episodic and short-term events with both

positive and negative impacts are not treated as

standalone impact indicators, and this is important for

eliminating lag influence generated by

commercialisation process. To achieve the

abovementioned evaluation goals and to correctly

indicate the dynamics of the IPM segment impact on

the income generated by IBM, the dedicated Average

Change Rate tool was selected. This tool is used to

analyse changes in results, and evaluate impact over

long periods of time. The method of calculation is

presented in equations 1 and 2 (Sharpe et al. 2014;

Triola, 2014).

()

2

(1)

1

logy log

1

n

it

Vi

i

it

v

nv

(1)

where:

y

Vi

– is the geometric mean of chain indices of the

analysed variable v

i

, during the entire period of

analysis,

v

i

– is the next, annual value in the time series of the

analysed variable v

i

,

()

(1)

it

it

v

v

– is the annual value of the chain index of the

analysed variable v

i

,

i – is the next value in the chain index,

n – – expresses the number of elements in the time

series of the analysed variable v

i

.

Vi Vi

T y 1 ×100

(2)

where:

Vi

T

– is the average rate of change of the analysed

variable v

i

, during the entire period of the study,

Vi

y

– is the geometric mean of the chain indices of the

analysed variable v

i

, during the entire period of

analysis.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Empirical Data

The source documentation describes financial results

of the IPM segment over the research period. Table 1

and table 2 illustrates the input data in time series,

allowed to identity in the source documentation. The

four columns of the data series presented in Table 1

illustrates the IPM segment.

The Economic Impact of Intellectual Property Management: Towards Model of Intellectual Property Management

75

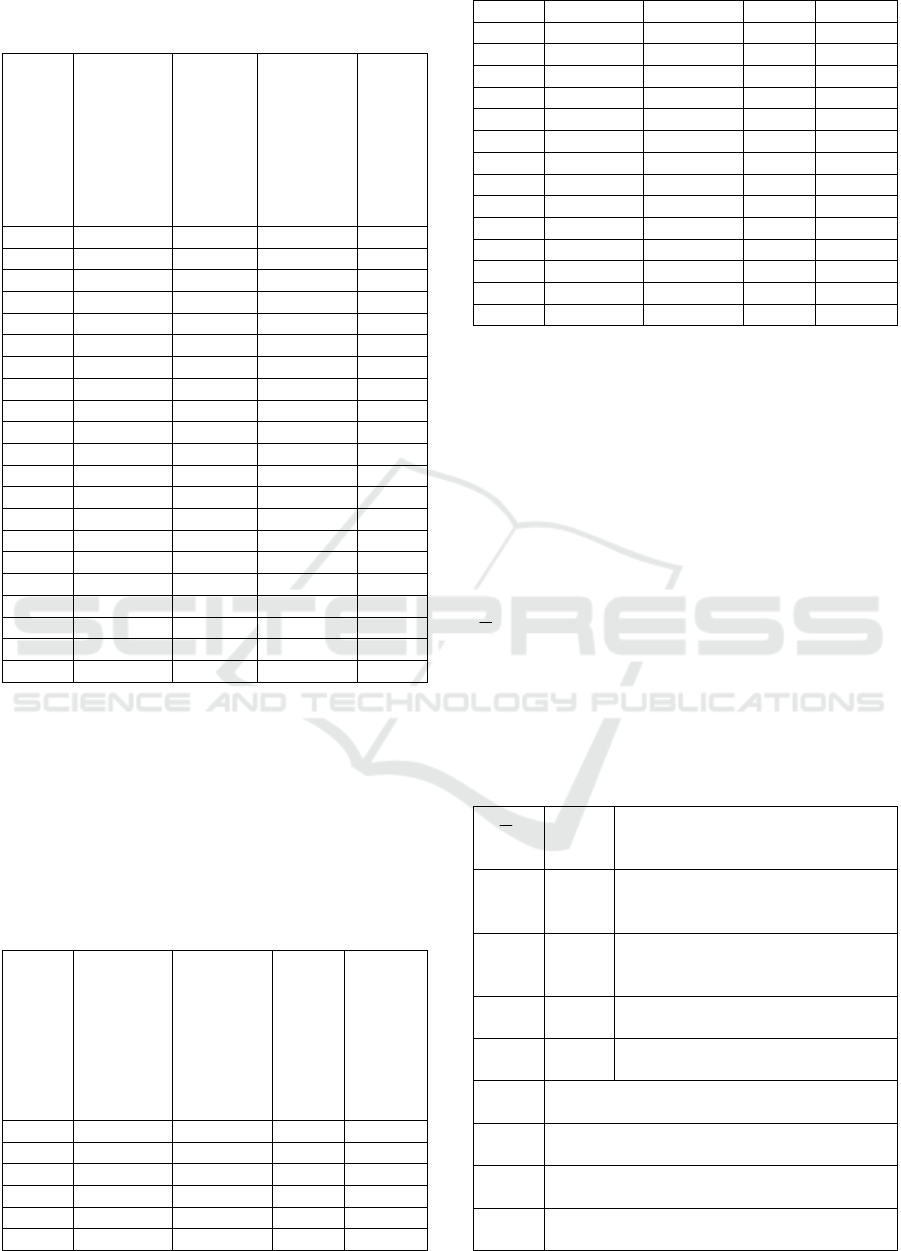

Table 1: The input data identified over the entire research

period – description of the IPM segment.

Year/ Variable

Sales and other

transfers of intellectual

property income before

tax [USD millions]

Licensing/royalty-

based income before

tax [USD millions]

Custom

development income

before tax

[USD millions]

Total IPM Income

before tax

[

USD millions

]

1998 363 302 436 1 100

1999 628 646 232 1 506

2000 915 590 223 1 728

2001 736 515 284 1 535

2002 511 351 238 1 100

2003 562 338 268 1 168

2004 466 393 310 1 169

2005 236 367 345 948

2006 167 352 381 900

2007 138 368 452 958

2008 138 514 501 1 153

2009 228 370 579 1 177

2010 203 312 639 1 154

2011 309 211 588 1 108

2012 323 251 500 1 074

2013 352 150 320 822

2014 283 129 330 742

2015 303 117 262 682

2016 27 214 1 390 1 631

2017 21 252 1 193 1 466

2018 28 275 723 1 026

(Source: IBM, Annual Report, 1998, p. 64; 1999, p. 64;

2000, p. 64; 2001, p. 70; 2002, p. 81; 2003, p. 94; 2004, p.

63; 2005, p. 68; 2006, p. 80; 2007, p. 84; 2008, p. 60; 2009,

p. 89; 2010, p. 62; 2011, p. 70; 2012, p. 70; 2013, p. 78;

2014, p. 33; 2015, p. 76; 2016, p. 84; 2017, p. 78; 2018, p.

70).

The first column in Table 2 contains the total income

of IBM, before tax.

Table 2: The input data identified over the entire research

period – description of the entire IBM.

Year/ Variable

IBM – total

income before taxes

[USD millions]

Expenditure on

R&D activities

[USD millions]

Number of

acquired companies

Total Expenses

on acquisitions

[millions USD]

1998 9 040 5 046 9 828

1999 11 757 5 273 17 1 551

2000 11 534 5 151 9 511

2001 10 953 5 290 2 1 082

2002 7 524 4 750 12 3 958

2003 10 874 5 077 9 2 536

2004 12 028 5 673 14 2 111

2005 12 226 5 842 16 2 022

2006 13 317 6 107 13 4 817

2007 14 489 6 153 12 1 144

2008 16 715 6 337 15 6 796

2009 18 138 5 820 6 1 471

2010 19 723 6 026 17 6 538

2011 21 003 6 258 5 1 849

2012 21 902 6 302 11 3 964

2013 19 524 6 226 10 3 219

2014 19 986 5 595 6 608

2015 15 945 5 247 14 3 555

2016 12 330 5 751 15 5 899

2017 11 400 5 787 5 134

2018 11 342 5 397 2 49

(Source: IBM, Annual Report, 1998, p. 64; 1999, p. 64;

2000, p. 64; 2001, p. 70; 2002, p. 81; 2003, p. 94; 2004, p.

63; 2005, p. 68; 2006, p. 80; 2007, p. 84; 2008, p. 60; 2009,

p. 89; 2010, p. 62; 2011, p. 70; 2012, p. 70; 2013, p. 78;

2014, p. 33; 2015, p. 76; 2016, p. 84; 2017, p. 78; 2018, p.

70).

Column two in Table 2 contains some additional time

series, such as the expenditure on R&D activities, and

columns three and four presents the number of

acquired companies and expenses on acquisitions,

respectively. Table 3 presents the variables used in

the analysis and evaluation.

Vi

T

– symbol of the calculated average rate of

change,

v

i

– symbol of the time series input data.

Table 3: Time series of variables obtained during the

research for all components of the IPM segment and the

IBM total income, over the period of 1998-2018.

Vi

T

v

i

Name of the analysed input data

variable over the period of 1998–

2018

Ast

ipm

st

ipm

Time series of the IPM sales and

other transfers of intellectual

property income before tax.

Alr

ipm

lr

ipm

Time series of the IPM

licensing/royalty-based income

before tax.

Acd

ipm

cd

ipm

Time series of the IPM custom

development income before tax.

Ati

ipm

ti

ipm

Time series of the total IPM income

before tax.

At

ibm

t

ibm

– Time series of the total IBM income

before tax.

Ard

sp

rd

sp

– Time series of research and development

spending

Aac

nq

ac

nq

– Time series of the number of acquired

businesses

Aac

q

ac

q

– Times series of the total acquisition

expenses

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

76

The first four variables presented in Table 3 are used

to achieve the first step of the second stage of the

analysis and evaluation. To accomplish the other step

of the second stage of the analysis and evaluation,

Equation 3 was applied to indicate the share of the

IPM segment in relation to the total income before tax

of the IBM.

()

()

it

ipm

ibm t

v

vtz

t

(3)

where:

vtz

ipm

– annual value of IPM subsequent variable data

series from Table 1 and 2, to annual value of the total

income of IBM, before tax, over the research period;

v

i(t)

– annual value of IPM subsequent variable data

series from Table 1 and 2;

tibm

(t)

– annual value of the total income of IBM,

before tax;

z – the subsequent IPM source variable presented in

Table 1 and 2;

t – following year in the time series.

Equation 3 introduces time series variables

representing the ratio of each IPM segment source

variable (as presented in Table 3) income before tax

of the entire IBM over the research period. The ratio

variables are presented in Table 4, and were used to

calculate the average change rate (according to

Equations 1 and 2). Using the same methodology

allowed a direct comparison of the calculated results

to be performed.

Vi

T

– symbol of the calculated average rate of

change,

vtz

ipm

– symbol of the time series input data.

Table 4: The variables representing the ratio of each IPM

segment.

Vi

T

vtz

ipm

Name of the analysed input data

variable over the period of 1998–

2018

Avt1

ipm

vt1

ipm

Time series of the IPM sales and

other transfers of intellectual

property income before tax to total

IBM income before tax ratio.

Avt2

ipm

vt2

ipm

Time series of the IPM

licensing/royalty-based income

before tax to total IBM income

before tax ratio.

Avt3

ipm

vt3

ipm

Time series of the IPM custom

development income before tax to

total IBM income before tax ratio.

Avt4

ipm

vt4

ipm

Time series of the total IPM income

before tax to total IBM income

before tax ratio.

Income before tax was used as financial results of the

IPM segment over the research period, obtained from

the source documentation. There was an identified

limitation in the performed evaluation as cash flow

could not be analysed for the IPM segment. The

results of the two stages of this study are presented in

the following sections.

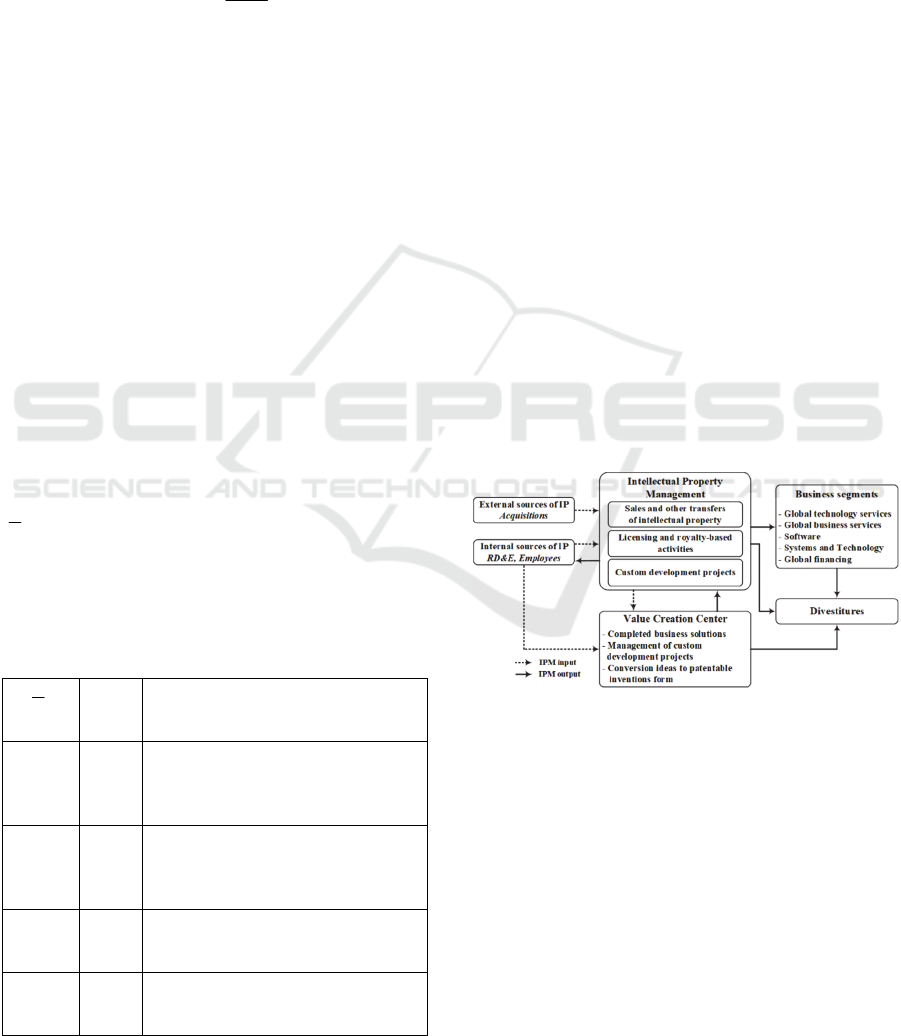

4.2 Complex Design of IPM Model

based on the IBM Environment

The first stage of this research was dedicated to

identifying and describing the complex design of the

IPM segment. Many changes in the IPM were tracked

over the research period of this study. The conceptual

design of the configuration and cooperation of the

IPM segment in the complex IBM enterprise is

illustrated in Figure 1. The links presented in the

diagram occur throughout the entire research period,

but with different levels of intensity and scope.

Intensity can be measured by the number of

recognised intangible assets, while scope represents

the number of intangible asset types of IPM sources

and outputs. For example, and in relation to outputs,

at the beginning of the research period, IPM mostly

powered systems and technology and software

business segments, but later in the period, it powered

other additional business segments such as global

technology services and global business services.

Figure 1: Conceptual design of the IPM model based on the

IBM environment.

Over the research period, IBM was involved in the

divestiture of selected business operations, such as

Hitachi's hard disk drive technology in 2002 for USD

2.05 billion and ThinkPad to Lenovo in China for

USD 2.3 billion in 2005 (IBM, 2019). The acquired

intellectual property and other intangible assets

constituted a direct supply of some of the business

operations selected as strategic priorities for

divestiture. In these transactions, IPM had its share in

the field of technical and technological solutions.

However, divestitures were also supported directly

from the Value Creation Centre (VCC). This centre is

The Economic Impact of Intellectual Property Management: Towards Model of Intellectual Property Management

77

responsible for completing business solutions

obtained from the R&D segment, managing custom

development projects where some results from IPM

were systematically used, and converting ideas

gathered from employees’ information patentable

forms and sending them to the IPM segment for the

finalising patenting process in USPTO. The custom

projects create necessary solutions through

initialising dedicated projects in the R&D segment, as

well as put as priority to acquire from outside the

specific intangible values though the IPM. Hence, the

link between the VCC and the IPM, and the IPM and

R&D was bidirectional, intensive and wide scoped,

with close cooperation. Such a close cooperation was

necessary to transform the various intangible assets

obtained through acquisitions, along with those

required by dedicated custom projects, R&D

segments, business segments or businesses selected

for divestiture. Acquisitions bring many assets, and

among them, intangible assets were indicated

according to GAAP and SFAS, such as goodwill,

completed technology, in-process R&D, patents and

trademarks, client lists and relationships, but

excluding contracts, clients with contracts/backlog

and other intangible assets. Acquisitions were

performed regularly and during the research period;

IBM acquired 219 businesses. Using Equations 1 and

2, the number of acquired businesses (Aac

nq

)

decreased over the research period, year to year, by

an average of 7.24%. At the same time, the

acquisition expenses (Aac

q

) also decreased year to

year, by an average of 13.18%. However, the R&D

spending was managed through the entire research

period at a flat level, and the average R&D spending

(Ard

sp

) increased year to year, by an average of only

0.34%. Acquired businesses are mostly from the

Information Technology sector. A selection of

acquisitions is a part of the multidimensional

innovation development strategy. One of the

dependent strategies is dedicated to IPM segment and

plying own role in the entire system of orchestrated

strategies. Intangible assets obtained through

acquisitions are partially directly included in current

business solutions. Some of them are transformed

(through R&D) to form required by other segments,

and finally, some intellectual properties are patented

and/or commercialised. Hence, the IPM consists of

the following subsegments of business activities:

sales and other transfers of intellectual property,

licensing and royalty-based activities,

custom development projects.

These activities manage all intangible assets obtained

through acquisitions and ideas coming from

employees. The distinctive characteristic of the IPM

complexity is to maximise the use of various

intangible assets in many diversified business fields.

The presented concepts imply wide usage of

intangible assets. The presented design concept,

works as a form of template for large enterprises,

which is able to manage many intangible assets in a

profitable way. Its outputs are wide in provided

business types; from custom development projects, to

five business segments and divestitures of unwanted

businesses, from services in financing of business

ventures, through the most advanced technological

solutions in nanoelectronics and bionanoelectronics

to wide offer of computer software (often acquired)

and comprehensive business services including

outsourcing, reengineering or business

transformation outsourcing (IBM, 2019). Such a

multi-business environment allows IPM to make

profit through precisely and carefully selected

acquisitions and the collection of any intangible

assets from R&D and employees. This raises the

question of whether the IPM segment is profitable.

This question is explored and addressed in the next

subsection.

4.3 Economic Impact of the IPM

Profitability is the most important economic measure.

One of the most common profitability measures is

income before tax, where the value of which directly

indicates the profit or loss. Table 1 presents the source

of the time series variables. The first four columns

contain four variable values, taken over the research

period that describe the IPM segment income before

tax. These variables were used to analyse and

evaluate the IPM as a standalone segment. The fifth

column contains values of the total IBM income,

before tax. There are only positive values that indicate

that each year of the research period, the IPM

segment and the IBM corporation generated profit.

This raises the question about dynamic change of

these variables over the research period. The results

of the calculation performed in the first step of the

second stage covered the first five variables as

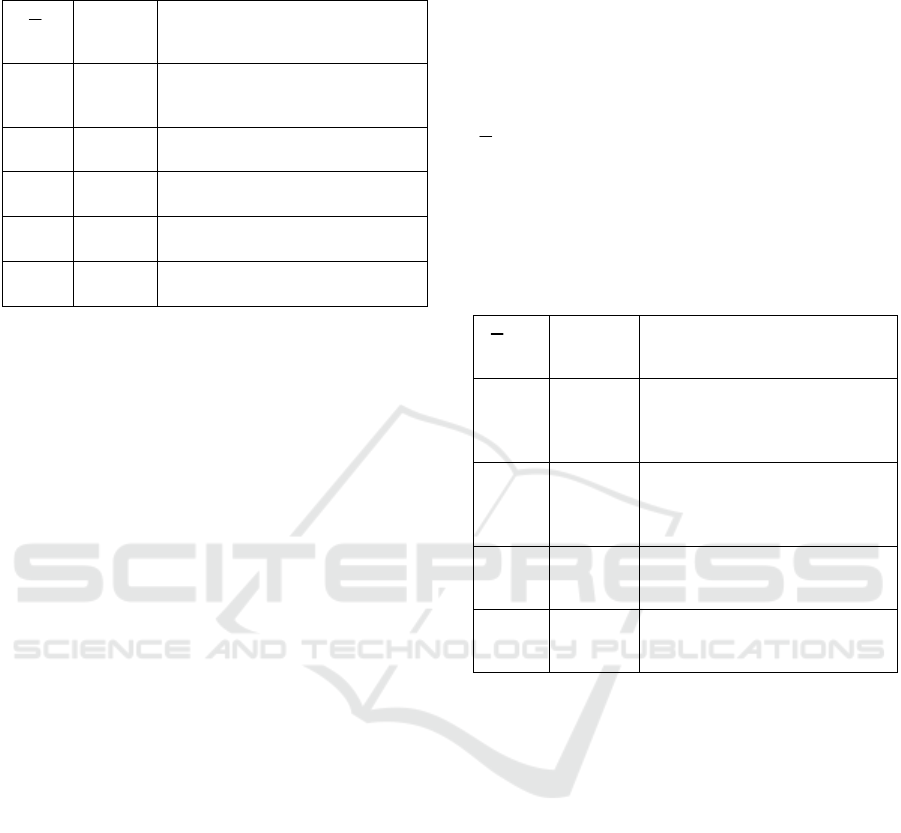

presented in Table 3, and are presented in Table 5.

Vi

T

– symbol of the calculated average rate of

change,

Av

[%]

– the calculated value of the average rate of

change.

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

78

Table 5: The average change rate of income before tax

describing IPM segment.

Vi

T

Av

[%]

Name of the analysed input data

variable over the period of 1998–

2018

Ast

ipm

-12.02%

IPM sales and other transfers of

intellectual property income

before tax.

Alr

ipm

-0.47%

IPM licensing/royalty-based

income before tax.

Acd

ipm

2.56%

IPM custom development income

before tax.

Ati

ipm

-0.35% IPM total income before tax.

At

ibm

1.14% Total IBM income before tax

The first three variables represent the main activities

carried out in the IPM segment over the research

period (Table 5). The fourth variable is the IPM

segment total income before tax. Although all values

of variables indicated profit, the calculated dynamics

showed that for sales and other transfers of

intellectual property income before tax, the profit

decreased over the research period, year on year, by

an average of 12.02%. Similarly, for

licensing/royalty-based income before tax, the profit

decreased over the research period, year on year, by

an average of 0.47%. It can be concluded that

commercialisation of intellectual property achieved

by sales and other transfers and licensing became less

profitable over the research period. The custom

development income before tax, representing

participation in the management of custom

development projects (organised and managed in

VCC, see Figure 1), indicated that profit increased

over the research period, year on year, by an average

of 2.56%. Similarly, for the entire IPM segment

income before tax, profit decreased over the research

period, year on year, by an average of 0.35%. The

calculation reveals that the total IBM income before

tax increased over the research period, year on year,

by average 1.14%. It can be concluded that the profit

generated by custom development income increased

faster than profit generated by the entire IBM, while

the profit generated by the entire IPM segment

income before tax decreased in the research period. In

conclusion, not all commercialisation activities of

intellectual property generated increased dynamics in

profit. Two intellectual property commercialisation

activities brought an alarming decrease in profit: the

sales and another transfer of intellectual property and

licensing/royalty-based. In the IBM case, the IPM

segment decrease profit, while the entire IBM income

before tax increases.

The second step of the second stage of research

analysis and evaluation consisted of the measure of

dynamic share variables of the IPM segment to total

income of IBM, before tax. The results from this step

showed a dynamic change in the generated profit of

the IPM segment activities compared to the dynamic

change of the total profit of IBM. The calculation

results are presented in Table 6.

Vi

T

– symbol of the calculated average rate of

change,

Av

[%]

– the calculated value of the average rate of

change.

Table 6: The average change rate of the IPM segment

income before tax to the IBM income before tax ratio.

Vi

T

Av

[%]

Name of the analysed input data

variable over the period of

1998–2018

Avt1

ipm

-13.17%

The ratio of the IPM sales and

other transfers of intellectual

property income before tax to

total IBM income before tax.

Avt2

ipm

-1.76%

The ratio of the IPM

licensing/royalty-based income

before tax to total IBM income

before tax.

Avt3

ipm

1.23%

The ratio of the IPM custom

development income before tax

to total IBM income before tax.

Avt4

ipm

-1.64%

The ratio of the total IPM

income before tax to total IBM

income before tax.

The calculated results illustrate that the profit

generated from sales and other transfers of

intellectual property decreased at the highest level

over the research period, year on year, by an average

of 13.17% when compared to the profit generated by

IBM. Similarly, the dynamics of profit generated by

licensing/royalty-based activities also decreased over

the research period, year on year, by an average of

1.76% when compared to the profit generated by

IBM. These results not only confirm the previous

conclusions for the IPM segment standalone, but also

show deeper divergence of dynamic profit generation

in the IBM. The dynamics of profit generated by IPM

custom development of intellectual properties

increased over the research period, year on year, by

an average of 1.23% when compared to the profit

generated by IBM. Furthermore, the dynamics of

profit generated by the IPM segment decreased over

the research period, year on year, by an average of

1.64% when compared to the profit generated by

IBM. Based on this result, it can be concluded that

intellectual property custom development increased

The Economic Impact of Intellectual Property Management: Towards Model of Intellectual Property Management

79

significantly faster than the dynamics of the total IBM

profit. However, the entire IPM segment brought

decrease profit, while the dynamics of the total IBM

profit increases.

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

The complexity theory encourages a different

managerial approach than the sophisticated and

reductionist method (Espinosa and Walker, 2017).

Instead of selecting strict and precisely defined

courses of action in complex systems, the managerial

role is to provide correctly defined goals, necessary

resources and verify trajectory of development.

Hence, in the case of IPM, it does not appear to be

enough. The presented complex design maximises the

spectrum of use of various types of intangible assets

in a diversified business field and in the business-to-

business project cooperation. Only in such conditions

does the IPM segment appear to bring the full benefit,

but it also requires orchestration with the entire

multidimensional innovation development strategy.

Dealing with intellectual property alone, without

business context, control and correction of strategic

alignment according to changes in socio-economic

environment, can cause serious difficulties in

achieving success. Hence, not all commercialisation

activities managed in the IPM segment generated

profit. The IBM is the unquestionable leader in the

number of patents obtained from the USPTO. Thus,

the obtained results indicate that the IPM segment and

custom development of intellectual property,

managed in custom development projects, can be

mentioned as drivers of profit generated by the entire

company, because their dynamic of increasing profit

is higher than the dynamic of increasing profit of

IBM. The profit generated by the entire IBM

enterprise increased over the research period, year on

year, by an average of 1.14%. While the profit of the

custom development of intellectual property,

representing participation in the management of

custom development projects, increased over the

research period, year on year, by an average of

2.56%; approximately 2.5 times faster than IBM. The

profit generated by the IPM segment, measured by

income before tax, slightly decreased over the

research period, year on year, by an average of 0.35%.

The dynamics of generated profit show that the

custom developed intellectual property associated

with projects implemented on individual orders of

business clients is the most profitable, and brought the

most significant positive economic impact. The last

two activities; the sales and other transfers and

licensing/royalty-based of intellectual property

generated profit over the research period. But the

dynamic of income before tax indicates a significant

reduction in the evaluation of the IPM segment

standalone over the research period, year on year, by

an average of 12.02% and 0.47% respectively.

Similarly, the dynamics of the profit of these two

activities in relation to the dynamics of the profit

generated by entire IBM, also decreased over the

research period, year on year, by an average of

13.17% and 1.76% respectively. It means that these

two activities become less profitable. Thus, the

acquisitions strategy should be corrected and shifted

to obtain properties, which support custom

development of the internal IP.

In conclusion, not all commercialisation activities

of intellectual property generated increasing

dynamics in profit. From a strategic point of view, the

situation of losing profit and addressing this issue

should have been recognised faster than after twenty-

one years. Specifically, for sales and other transfers

of intellectual property decreasing at that magnitude,

this should have been a warning. In such a case, it is

imperative to act to reverse this dynamic. This is an

area where the new complexity approach still requires

specifically designed and tested tools for analysing

and evaluating achieved results, and comparing them

to a dedicated strategic subject and target. Achieving

success in IPM requires an orchestration of both the

classic and complex managerial approach.

In existing literature, there is a wide discussion about

the use of intellectual property, including incentives

from the law to obtain patent protection (Alimov and

Officer, 2017; Holgersson et al. 2017). Both

proponents and sceptics present coherent arguments

related to the management of intellectual property

within businesses. As expected, there is no universal

application for success in intellectual property

management. Hence, the presented research results

show that large IPM corporations have a better

chance to achieve profit due to a wider spectrum of

commercialisation activities, and using intellectual

properties in dedicated custom development projects

is a commonly used approach in micro and small IT

companies. On the contrary, the presented results

illustrate that not all IPM-related activities are drivers

of profit in modern business. These activities are

subject to the same rules as the individually

developed and implemented enterprise strategies.

IPM does not guarantee success and a source of

competitive advantage. Poorly managed intellectual

property can bring even a large business to its

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

80

downfall. The results show that IPM does not

guarantee better profit and success, even if the

enterprise is innovative. The final conclusion is that

not all activities of IPM generated increasing

dynamics in profit which must be taken into account

while design own IPM model.

REFERENCES

Afauh, A. 2009. Strategic Innovation: New Game

Strategies for Competitive Advantage. Routledge. New

York.

Alimov, A., Officer, M. 2017. Intellectual property rights

and cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Journal of

Corporate Finance, 45, 360-377.

Arora, A., Athreye, S., Huang, C. 2010. Returns to

Patenting: A Literature Review, Report Prepared for the

Project of Intellectual Property Rights and Returns to

Technology Investment. The UK Intellectual Property

Office. London.

Baraldi, A. Cantabene, C. Perani, G. 2014. Reverse

causality in the R&D – patents relationship: an

interpretation of the innovation persistence. Economics

of innovation and New Technology, 23(3), 304-326.

Bjelland, O. Chaptman Wood, R. 2008. An inside view of

IBM’s ‘innovation Jam’. MIT Sloan Management

Review, 50(1) 32-40.

Espinosa, A., Walker, J. 2017. A complexity approach to

sustainability. Theory and practice. World Scientific

Publishing Europe Ltd. London.

Hagedoorn, J., Zobel, A. 2015. The role of contracts and

intellectual property rights in open innovation.

Technological Analysis Strategic Management, 27(9)

1050-1067.

Hardagon, A., Douglas, Y. 2001. When Innovations Meet

Institutions: Edison and the Design of the Electric

Light. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(3) 476-

501.

Henkel, J., Baldwin, C.Y., Shih, W. 2013. IP modularity:

profiting from innovation by aligning product

architecture with intellectual property. California

Management Review, 55(4) 65-82.

Holgersson, M., Granstrand, O., Bogers, M. 2017. The

evolution of intellectual property strategy in innovation

ecosystems: Uncovering complementary and substitute

appropriability regimes. Long Range Planning, 50(6)

617-634.

IBM, 2013. Made in IBL Labs: 10 Chip Breakthroughs in

10 Years. IBM Publisher. Armonk.

IBM, 2019. Annual Reports. From the Period 1997-2018.

IBM Publisher. Armonk.

Junghans, C., Levy, A., Sander, R., Boeckh, T., Heerma, J.,

Regierer, Ch. 2006. Intellectual Property Management.

Willey & Sons. New York.

Kaplan, R., Norton, D. 2004. Strategy Maps: Converting

Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes. Harvard

Business School Press. Boston.

Kianto, A., Sáenz, J., Aramburu, N. 2017. Knowledge-

based human resource management practices,

intellectual capital and innovation. Journal of Business

Research, 81, 11-20.

Lanjouw, J. O., Schankerman, M. 2004. Patent quality and

research productivity: measuring innovation with

multiple indicators. The Economic Journal, 114, 441-

465.

Manzini, R., Lazzarotti, V. 2016. Intellectual property

protection mechanisms in collaborative new product

development. R&D Managmenet, 46(2) 579-595.

Meliciani, V. 2000. The relationship between R&D,

investment and patents: a panel data analysis. Applied

Economics, 32(11), 1429-1437.

Ness, R. B. 2012. Innovation Generation: How to Produce

Creative and Useful Scientific Ideas. Oxford University

Press. Oxford.

Palfrey, J. 2011. Intellectual Property Strategy, MIT Press.

Boston.

Richardson, K., 2008. Managing Complex Organizations:

Complexity Thinking and the Science and Art of

Management. Emergence & Complexity Organization.

10(2), 13-26.

Sagasti, F. 2004. Knowledge and Innovation Development.

Edward Elgar Publisher. New York.

Schmookler, J. 1951. Invention and Economic

Development, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Philadelphia.

Sessions, B., Hamaty, Ch. 2016. Corporate Perspectives on

IP Strategy. CreateSpace Independent Publishing

Platform. New York.

Sharpe, N., Veaux, R., Velleman, P. 2014. Business

statistics, Pearson Publisher. Boston.

Sierotowicz, T. 2015. Patent activity as an effect of the

research and development of the business enterprise

sectors in the countries of the European Union. Journal

of International Studies, 8(2), 31-43.

Sierotowicz, T. 2017. The economic aspect of the

efficiency of patent activities based on case studies of

leading ICT enterprises. Queen Mary Journal of

Intellectual Property, 7(3), 343-355.

Stoneman, P. 1987. The Economic Analysis of

Technological Change. Oxford University Press.

Oxford.

Thornhill, S. 2006. Knowledge. innovation and firm

performance in high- and low-technology regimes.

Journal of Business Venturing, 21(5), 687-703.

Triola, M. 2014. Essentials of Statistics. Pearson Publisher.

London.

USPTO, 2019. The United States Patent and Trademark

Office. Available at: http://www.uspto.gov/ (accessed:

December 8, 2019).

USSEC, 2019. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Available at: https://www.sec.gov/? (accessed:

December 8, 2019).

The Economic Impact of Intellectual Property Management: Towards Model of Intellectual Property Management

81