Tailored Retrieval of Health Information from the Web for

Facilitating Communication and Empowerment of Elderly People

Marco Alfano

1,5

, Biagio Lenzitti

2

, Davide Taibi

3

and Markus Helfert

4

1

Lero, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

2

Dipartimento di Matematica e Informatica, Università di Palermo, Palermo, Italy

3

Istituto per le Tecnologie Didattiche, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Palermo, Italy

4

Lero, Maynooth University, Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland

5

Anghelos Centro Studi sulla Comunicazione, Palermo, Italy

Keywords: e-Health, Patient Empowerment, Communication, Health Information Seeking, User Requirements,

Structured Data, Search Engine.

Abstract: A patient, nowadays, acquires health information from the Web mainly through a “human-to-machine”

communication process with a generic search engine. This, in turn, affects, positively or negatively, his/her

empowerment level and the “human-to-human” communication process that occurs between a patient and a

healthcare professional such as a doctor. A generic communication process can be modelled by considering

its syntactic-technical, semantic-meaning, and pragmatic-effectiveness levels and an efficacious

communication occurs when all the communication levels are fully addressed. In the case of retrieval of health

information from the Web, although a generic search engine is able to work at the syntactic-technical level,

the semantic and pragmatic aspects are left to the user and this can be challenging, especially for elderly

people. This work presents a custom search engine, FACILE, that works at the three communication levels

and allows to overcome the challenges confronted during the search process. A patient can specify his/her

information requirements in a simple way and FACILE will retrieve the “right” amount of Web content in a

language that he/she can easily understand. This facilitates the comprehension of the found information and

positively affects the empowerment process and communication with healthcare professionals.

1 INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization (WHO),

empowerment is “a process through which people

gain greater control over decisions and actions

affecting their health” (WHO, 1998). It includes, as a

basic step, the acquisition of health/medical

information that helps patients/citizens to understand

medical conditions and treatments, acquire self-

confidence to discuss them with medical

professionals and, together, make the best-informed

decisions (Akerkar & Bichile, 2004; Smith, 2004).

The main source of health/medical information is,

nowadays, the World Wide Web (or Web, for short)

with the number of Web health information seekers

that have been steadily increasing over the years (Pew

Research Center, 2013; Taylor, 2010). Search engines

are more and more used as the main tools to provide

Web information. However, generic search engines

do not make any distinction among the users and

overload them with the amount of information. The

use of a search engine for Web information retrieval

entails a human-to-machine communication process

between the user (e.g., a patient) and the search

engine. It affects, among others, the amount,

comprehension and use of the found information.

This, in turn, may facilitate or complicate the human-

to-human communication process between patients

and healthcare professionals such as doctors (Smith,

2004).

Communication processes have been modelled in

various ways in the past decades. One of the most

famous communication model is the one introduced

by Morris in relation to its theory of signs (Morris,

1938). It is made up of three levels, i.e., syntactic,

semantic and pragmatic. It is paired up by another

communication model introduced by Shannon and

Weaver (Shannon, 1949) that tackles the problems of

communication at the technical, semantic and

effectiveness levels. The connection of the two

Alfano, M., Lenzitti, B., Taibi, D. and Helfert, M.

Tailored Retrieval of Health Information from the Web for Facilitating Communication and Empowerment of Elderly People.

DOI: 10.5220/0009576202050216

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2020), pages 205-216

ISBN: 978-989-758-420-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

205

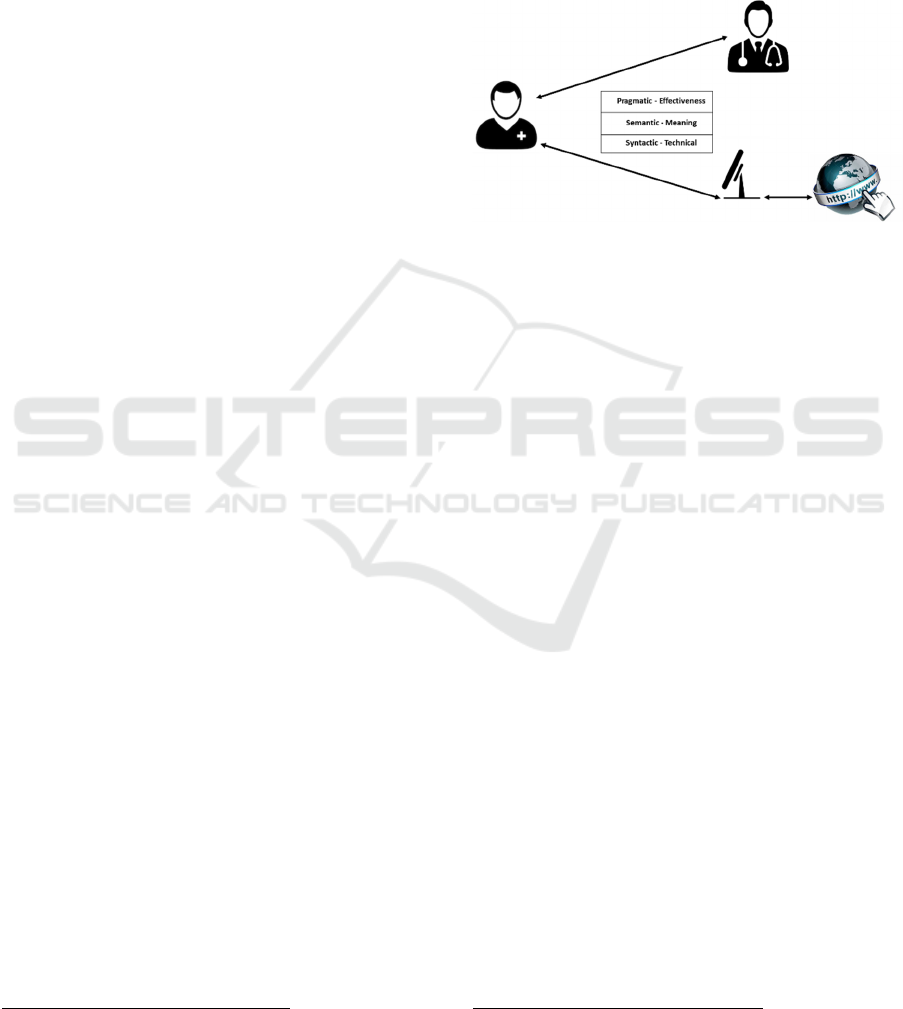

models, as shown in the next section, leads to the

following three levels (top down):

● Pragmatic - Effectiveness;

● Semantic - Meaning;

● Syntactic - Technical.

Although a complete communication process

should take place in order to allow patients/citizens to

fully understand and efficaciously use the found

information, a quick analysis of the three-level

communication model shows how a generic search

engine is only able to retrieve information from the

Web working at the syntactic-technical level, leaving

the semantic and pragmatic part of the

communication process in charge of the user. Elderly

people, in particular, may have great difficulties in

expressing their requirements, and understanding and

using the received information, as envisaged by the

semantic and pragmatic communication levels. This

prevents them, for example, from having a true

understanding of their medical conditions (semantic-

meaning level) and acquire the self-confidence to

communicate with their doctors and make a shared

and informed decision (pragmatic-effectiveness

level). Since a generic search engine is not able to

work at the three communication levels, it does not

constitute a real aid in the process of empowering a

patient/citizen, especially an elderly one. It can also

complicate the communication between a patient and

a healthcare professional. For example, the different

ways of dealing with the information found on the

Web can lead to an argument between a patient and a

doctor.

This work presents the characteristics and use of

a custom search engine, FACILE, that has been

created in order to satisfy the user information needs

and overcome the communication challenges

confronted during the search process. In particular,

FACILE allows a user to specify his/her information

requirements in a simple way. It, then, retrieves

tailored Web information by exploiting the Web

semantic capabilities provided by health-

lifesci.schema.org structured data. By doing so,

FACILE provides the “right” amount of Web content,

without overwhelming the user, and in a language that

he/she can easily understand. This positively affects

patient’s comprehension of conditions and treatment

alternatives and, ultimately, facilitates, his/her

empowerment process.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2

illustrates the problems and challenges presented by

the retrieval of Web health information in relation to

the expected communication process, together with

1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

the motivation of the present work. Section 3 presents

the characteristics and implementation details of the

FACILE custom engine that overcomes the problems

and challenges presented in Section 2. Section 4

presents the use and experimental results of FACILE.

Sections 5 and 6 present a discussion of the obtained

results and some conclusions.

2 BACKGROUND AND

MOTIVATION

“Engaging and empowering people & communities”

constitutes the first of the five strategies of the

“Framework on integrated people-centred health

services” of WHO (WHO, 2016). It calls for a

paradigm shift on the relation between

patients/citizens and health. In fact, empowered

patients have the necessary knowledge, skills,

attitudes and self-awareness about their condition to

understand their lifestyle and treatment options, make

informed choices about their health and have control

over the management of their condition/health in their

daily life (European Health Parliament, 2017; Alfano

et al., 2019a; Alfano et al., 2019b; Bodolica et al.,

2019; Bravo et al., 2015, Cerezo et al., 2016;

Fumagalli et al., 2015).

As seen in Section 1, the acquisition of

medical/health information is a basic step in the

empowerment process and the main source of

health/medical information is, nowadays, the Web

(Pew Research Center, 2013; Taylor, 2010; UK

national statistics, 2010; Instituto Nacional de

Estadística, 2010). Search engines are the main tools

used to retrieve information from the Web (Pletneva,

2011; Roberts, 2017). However, generic search

engines do not make any distinction among the users

and overload them with a huge amount of information

that is often outdated or of poor quality. Moreover,

the Web is full of information not easily

understandable since users, such as patients/citizens,

lack a specific expertise in the health domain.

Although, some of these problems might be

overcome with the advanced features of a search

engine, generic users, and mainly elderly people, do

not usually have the skills required to use such

features and avoid these problems. Specialized search

engines (PubMed

1

or Quertle

2

), on the other hand,

mainly work on medical literature and result quite

complex for generic users, and especially the elderly

ones. Finally, specialized health/medical websites

2

https://quertle.com/

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

206

(e.g., WebMD

3

, MedlinePlus

4

or Health on Net

Foundation Select

5

) are mainly built by hand so

presenting a limited and often outdated amount of

information (compared to what is available on the

Web). Moreover, they are often not free.

The retrieval of health information from the Web

requires a communication process between a user (an

elderly patient/citizen in our case) and a search

engine. Notice that a “complete” communication

process, usually, entails different levels of

communication. Many communication models exist

in the literature and a very famous model (if not the

most famous) is the one introduced by Morris in

relation to his theory of signs (Morris, 1938). It is

made up of three levels, i.e., syntactic, semantic and

pragmatic and it has been used in several works

dealing with human communication (Hahn &

Paynton, 2014; Cherry, 1966; Johnson & Klare,

1961). Shannon and Weaver, on the other hand,

present a mathematical theory of communication that

is focused on information transmission (Shannon,

1949). Even though they mainly deal with the

technical aspects of communication, they introduce

other two levels above the technical one, i.e., the

semantic and effectiveness levels, that are influenced

by the technical level.

Interestingly enough, the two models have been

connected by (Carlile, 2004) and an equivalence

between the terms at the three levels has been

established, in practice. We can then consider a

“unified” communication model that presents the

following levels (with the “semantic” term that has

been associated to “meaning” as indicated in

Watzlawick et al., 1967):

● Pragmatic-Effectiveness: How effectively

does the received information affect

behaviour?

● Semantic-Meaning: How precisely is the

meaning conveyed?

● Syntactic-Technical: How accurately can

the information be transmitted?

This communication model can be used, in

principle, for both human-to-human communication

(e.g., patient to doctor) and human-to-machine

communication (e.g., patient to machine), as shown

in Fig. 1. The human-to-human communication

mainly deals with the syntactic-semantic-pragmatic

aspects of the communication model, whereas the

human-to-machine communication mainly deals with

the technical-meaning-effectiveness aspects.

As seen in the Introduction, this work deals with

tailored retrieval of health information for user

3

http://www.webmd.com/

4

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/

comprehension and empowerment and, consequently,

improvement in the communication/interaction with

medical professionals. With a specific focus on

elderly people, the objective is to improve the overall

communication between a user and the search engine

so that he/she can easily express his/her requirements

through everyday language and obtain the “right” and

easy-to-understand amount of information.

Figure 1: “Unified” communication model.

An analysis of the communication process of a

generic search engine shows how it only works at the

syntactic-technical level by retrieving Web page

addresses (URLs) based on the keyword(s) specified

by the user. It has not been designed to understand the

user specific requirements (in the user own language)

and, thus, it is only able to provide the user with

generic information leaving him/her with the task of

selecting, understanding and using the retrieved

information (semantic and pragmatic part of the

communication process). As a consequence, non-

medical experts, and especially elderly people, can be

overwhelmed with the results and have great

difficulties in the comprehension and use of the found

information. This, in turn, reflects on their ability to

have a “true” two-way communication with their

doctors because, for example, they do not have a

complete understanding of their medical conditions

(semantic level)–when they do not misunderstand

them–and then are unable to make shared and

informed decisions (pragmatic level).

Since a generic search engine does not help much

in the process of empowering patients/citizens,

especially elderly ones, we have thought of creating a

custom engine that allows a user to specify his/her

information requirements in a simple way and

provides the “right” amount of Web content, in a

language that he/she can easily understand. This fully

complies with all three levels of the communication

model and provides a practical help to the

empowerment process.

5

http://www.hon.ch/

Tailored Retrieval of Health Information from the Web for Facilitating Communication and Empowerment of Elderly People

207

The next sections present the characteristics and

use of such a search engine, FACILE, that has been

built in order to satisfy the user information needs and

overcome the challenges confronted during the search

process.

3 A CUSTOM ENGINE FOR

TAILORED RETRIEVAL OF

HEALTH INFORMATION

FACILE is a custom search engine specifically

designed to facilitate the empowerment process of

patients/citizens through the acquisition of

knowledge online. Its objective is to support users in

the health information seeking process on the Web

according to their specific requirements.

The identification of the main requirements of the

health information seekers on the Web has been

carried out in (Alfano et al. 2019a) by analysing the

works presented in (Pletneva et al. 2011; Banna et al.,

2016; Roberts, 2017; Pian et al. 2017; Pang et al.,

2015; Keselman, 2008). This literature review,

although limited, has consistently shown the

following main requirements of health information

seekers:

- Language complexity;

- Information classification/customization;

- Information quality (mainly intended as

information trustworthiness).

FACILE has been developed, based on these

requirements by exploiting the semantic features of

the Web and in particular those related to structured

data and schema.org

6

with particular reference to its

health-lifesci extension

7

. The use of structured data

on the Web is increasing over the years and the

exploitation of structured data to collect information

from the Web, in different sectors, has proven to be

effective (Taibi et al. 2013, Dietze et al. 2017).

3.1 Use of schema.org and

health-lifesci Structured Data

As said above, we have investigated how to leverage

structured data to find suitable Web pages that satisfy

the requirements of health information seekers. To

this end, we have exploited the semantic information

available in the World Wide Web and, in particular,

the one provided by schema.org, an initiative funded

6

https://schema.org/

7

https://health-lifesci.schema.org/

by some major Web players, that aims to create,

maintain, and promote schemas for structured data on

the Internet. For the scope of the present work, we

consider the health-lifesci extension that contains 93

types, 175 properties and 125 enumeration values

related to the health/medical field.

We have performed an analysis of the health-

lifesci elements using the data made available by the

Web Data Commons initiative

8

. The Web Data

Commons (WDC) (Meusel, 2014) contain all

Microformat, Microdata and RDFa (Resource

Description Framework in Attributes) data extracted

from the open repository of Web crawl data named

Common Crawl (CC)

9

. The data released in

November 2018 have been used in this work. The

whole dataset contains about 2.5 billion pages and

about 37.1% of them contain structured data.

The dataset dump, used in our study, consists of

31.5 billion RDF n-quads

10

. These are sequences of

RDF terms in the form {s, p, o, u}, where {s, p, o}

represents a statement consisting of subject,

predicate, object, while u represents the URI of the

document from which the statement has been

extracted. From the whole dataset, we have selected

only the subset containing types, properties and

enumeration values of health-lifesci.schema.org.

3.2 Mapping Health Information

Seeker Requirements to schema.org

Elements

When talking of online health information seekers,

we can, mainly, consider two classes of users:

● Non experts (e.g., patients or citizens);

● Experts (e.g., physicians or medical

researchers).

These two categories have different requirements,

that can be connected to the language complexity and

the other user requirements presented above. It is,

then, important to understand which health-

lifesci.schema.org elements can be mapped to the

health information seeker requirements in order to use

the structured data present in the Web to deliver

tailored information to the user. In relation to the

language complexity user requirement, health-

lifesci.schema.org includes the MedicalAudience

element that indicates whether the content is more

suitable for a non-expert (Patient type) or an expert

(Clinician

and MedicalResearcher types, Alfano et

8

http://webdatacommons.org/

9

http://commoncrawl.org

10

https://www.w3.org/TR/n-quads/

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

208

Figure 2: Comparison of most recurrent health-lifesci.schema.org elements for non-expert and expert audiences.

al., 2019c). A preliminary analysis on the dataset

containing the health.life-sci.schema.org

quadruples, shows that the distribution of

schema.org elements heavily varies depending on

the audience property of the pages (when specified).

Figure 2 shows the comparison between the

normalized distribution of the most recurrent

health-lifesci.schema.org elements for non-expert

and expert audiences.

In order to proceed with a classification and

customization of information for the users, we have

preliminarily analysed the most searched types of

health/medical information on the Web, such as

medical conditions, therapies and drugs (Taylor,

2010; Pew Research Center, 2013, Pletneva et al.

2011). We have then verified that these types

appeared among the most recurring health-

lifesci.schema.org elements reported in Fig. 2 in

order to have enough data to be processed by

FACILE and provide an effective information

classification. At the end of this process, we have

selected the following health.life-sci.schema.org

elements for creating the classification of Web

pages (the definitions are taken from https://health-

lifesci.schema.org/):

● MedicalWebPage, indicates that the Web page

provides medical information.

● MedicalScholarlyArticle, indicates that the

Web page is a scholarly article in the medical

domain.

● MedicalCondition, indicates any condition of

the human body that affects the normal

functioning of a person, whether physically or

mentally.

● MedicalTherapy, indicates a medical

intervention designed to prevent, treat, and cure

human diseases and medical conditions.

● Drug, indicates a chemical or biologic

substance, used as a medical therapy, that has a

physiological effect on an organism. Used

interchangeably with the term medicine.

● MedicalCode, provides a code for a medical

entity.

● MedicalClinic, indicates a hospital or a medical

school.

● MedicalSpecialty, indicates a specific branch of

medical science or practice.

We have then taken the audience elements, i.e.,

Patient, Clinician and MedicalResearcher for the

language complexity, the above health.life-

sci.schema.org elements for the

classification/customization of information and

some schema.org elements related to data

provenance (e.g., author and publisher) for the

quality information (because the health-lifesci

extension does not present such elements). This has

brought us to create a mapping between the user

requirements and the schema.org

elements for the

two user categories. This mapping expands the one

presented in (Alfano et al., 2019a) and is reported in

Table 1.

These schema.org elements are used by

FACILE to retrieve Web pages and extract

information based on the user specific requirements.

As we will show in the next sections, by using

FACILE, users can easily and quickly find the right

amount of information that is reliable and, in a

language suitable to their health literacy level, in

full compliance with the three levels of the

communication model presented above. This, in

turn, improves their empowerment level and allows

a better communication/interaction with the

medical professionals.

Tailored Retrieval of Health Information from the Web for Facilitating Communication and Empowerment of Elderly People

209

Table 1: Mapping between schema.org elements and user requirements for the “non-expert” and “expert” user categories.

Language Complexity Information Classification Information Quality

Non-expert

Audience:

- Patient

Type of document:

- MedicalWebPage

- WebPage

Topic Classification:

- MedicalCondition

- MedicalTherapy

- Drug

- MedicalCode

- MedicalClinic

- MedicalSpecialty

Reliability:

- author

- publisher

- lastRevised

- datePublished

Expert

Audience:

- Clinician

- Medical Researcher

Type of document:

- ScholarlyArticle

- MedicalWebPage

Topic Classification:

- MedicalCondition

- MedicalTherapy

- Drug

- MedicalCode

- MedicalClinic

- MedicalSpecialty

Reliability:

- author

- publisher

- lastRevised

- datePublished

3.3 Facile Implementation

The mapping between user requirements and

schema.org elements, shown in the previous section,

has been used to build FACILE that provides the

different audience types with the proper Web contents

in terms of language complexity, information quality

and information classification. It expands an initial

version of the system that only takes into account the

language complexity user requirement (Alfano et al.,

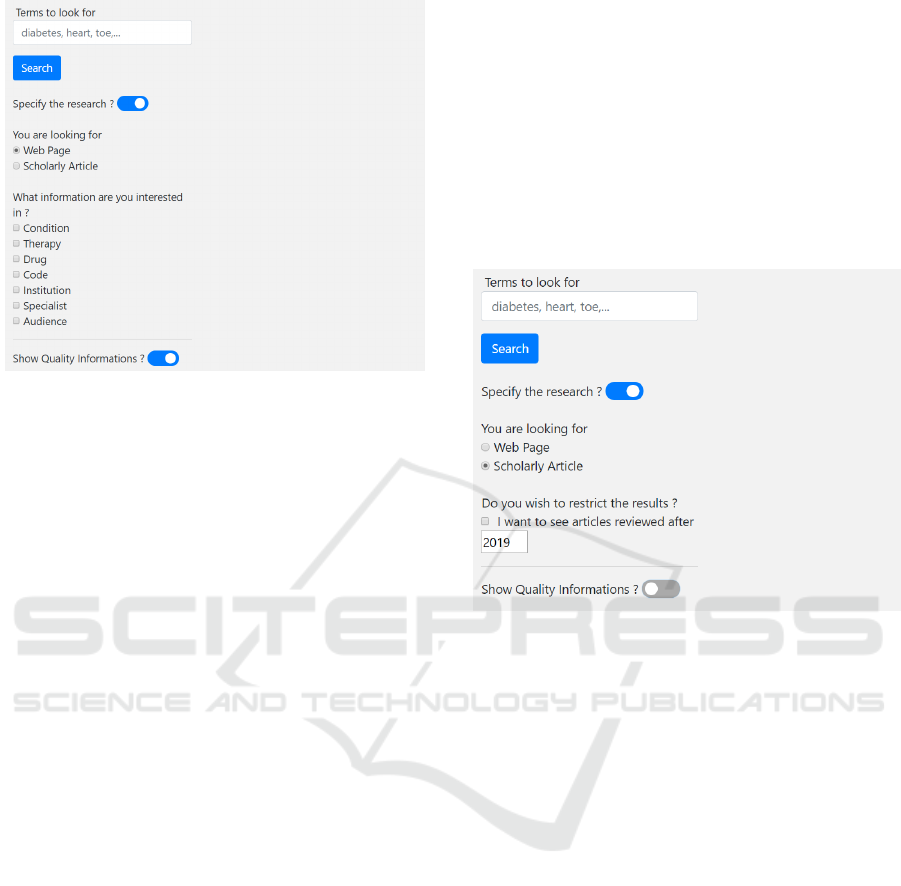

2019c). Fig. 3 shows the user interface of the FACILE

search engine available at the address

http://www.math.unipa.it/simplehealth/faciles.

Figure 3: FACILE user interface.

The user interface includes a simple text input, similar

to that of a generic search engine, where the user can

insert the term(s) to be searched. Moreover, the user

can decide to filter the results in order to get more

focused information and not be overwhelmed with the

amount of information that generic search engines

provide. This is simply done through the two switch

buttons shown in Fig. 3. The first switch button,

“Specify the research”, acts on the classification user

requirement. It allows to search for either medical

“Web Page” or for “Scholarly article” (Fig. 4).

Medical Web pages usually present a mixed language

and contain different types of information making

them suitable to different target audiences. Scholarly

articles are mostly research papers with a more

technical language and mainly targeted to medical

experts. The second switch button, “Show Quality

Information”, acts on the quality user requirement

and provides information such as the last time the

Web page has been reviewed, the publication date and

the author or the publisher of the page (when

available). This switch button does not filter out

results, but it shows additional information useful to

evaluate the information trustworthiness.

When selecting “Web Page”, with the first switch

button, some sub-filters appear in order to allow a

classification of the Web pages in terms of the

required type of medical information (Fig. 4).

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

210

Figure 4: Web page sub-filters.

The Web Page sub-filters can be activated through

checkboxes that can be easily selected by a user with

no specific knowledge (such as an elderly patient),

because they indicate common terms in the health

domain. More than one checkbox can be selected

each time and the filtering will be performed using

the mapping of Table 1 and providing the following

information:

- Condition: It will present the pages that contain

a description of a medical condition and the

values of the properties related to

MedicalCondition schema.org element.

- Therapy: It will present the pages that contain

information about a therapy and the values of the

properties related to MedicalTherapy schema.org

element.

- Drug: It will present the pages that contain the

information about a medicine and the values of

the properties related to Drug schema.org

element.

- Code: It will present the pages that contain the

code of a medical condition and the values of the

properties related to MedicalCode schema.org

element. The code, together with the coding

system, can be used to look on specialized

website to find a specific condition/part of the

body/therapy/drug, or other useful information.

- Institution: It will present the pages that contain

the institutions (e.g., hospitals) that deal with a

medical condition and the values of the

properties related to MedicalClinic schema.org

element.

- Specialist: It will present the pages that contain

the values of the properties related to

MedicalSpecialty schema.org element among

which the medical specialists that deal with a

medical condition.

- Audience: It will indicate the target audience of

the Web page (patient/clinician/medical

researcher) and the values of the properties

related to MedicalAudience schema.org element.

Finally, when a user is interested in finding more

technical information, he/she can select “Scholarly

Article”. He/she will also have the possibility to

specify a year in order to get the articles that have

been reviewed that year or later (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Scholarly Article sub-filters.

4 EXPERIMENTAL USE

FACILE, as shown in the previous section, has been

designed and implemented to be used by different

user typologies, i.e., medical experts or non-experts.

Nevertheless, in relation to what discussed

previously, we have executed some tests to evaluate

FACILE effectiveness and usefulness for its use with

non-experts and mainly with elderly people.

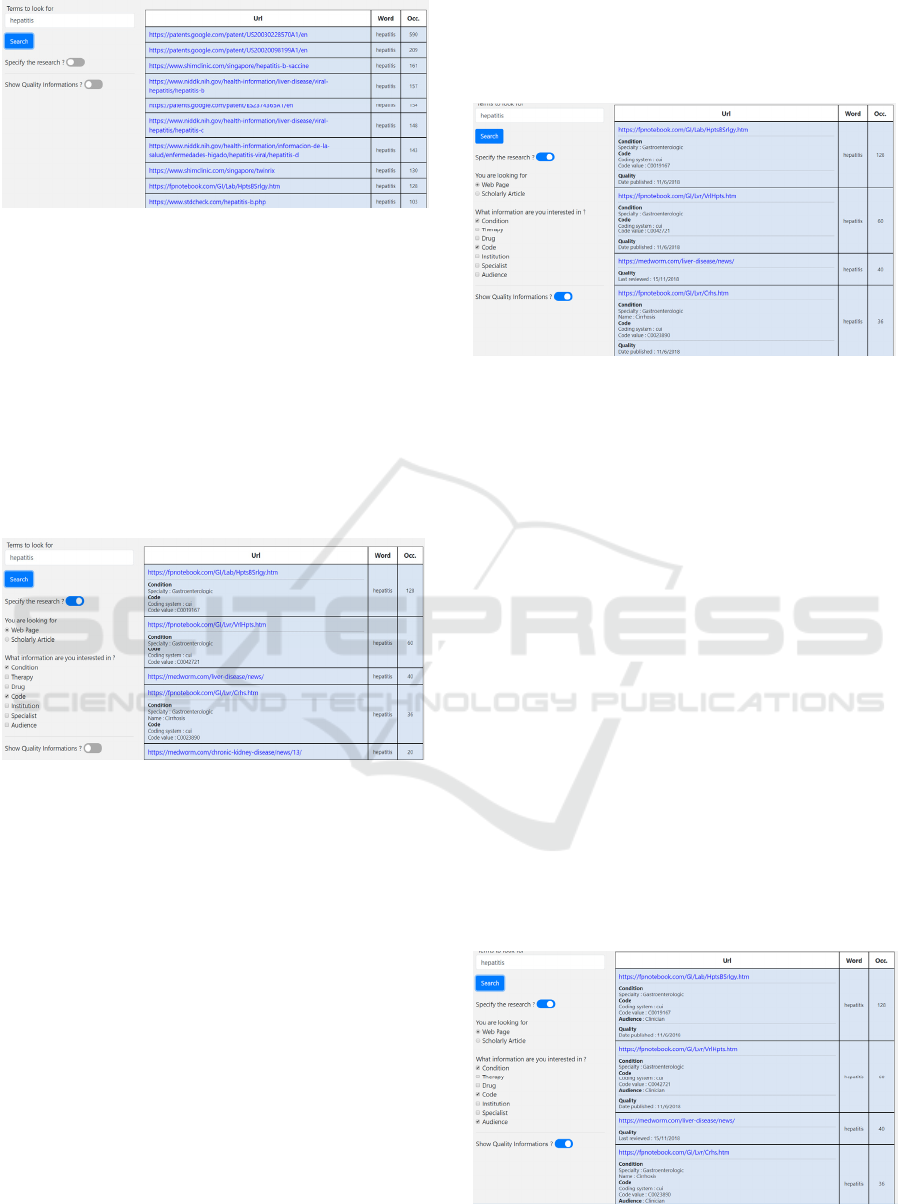

Preliminarily, notice that FACILE can be used as

a generic search engine by inserting any keyword on

the text input (Fig. 3) and receiving, at most, the top

fifty results. Notice that a user usually analyses the

first twenty-five–thirty results when using a generic

search engine such as Google™ (Alfano et al. 2019b).

Thus, from this point of view, the user is not penalized

by using FACILE even though it is not using the

whole Web but only the part that contains schema.org

structured data. Thus, if we search for the hepatitis

keyword, FACILE will provide the first fifty URLs

that present the higher number of hepatitis

occurrences (Fig. 6)

Tailored Retrieval of Health Information from the Web for Facilitating Communication and Empowerment of Elderly People

211

Figure 6: First results of generic search for hepatitis

keyword.

The usefulness of FACILE can be appreciated as soon

as the “Web page” filter and some of its sub-filters are

used. In the example of Fig. 7, the “Condition” and

“Code” sub-filters are checked. In this case FACILE

provides just ten results so reducing the number of

pages to be analysed and focusing to the Web content

of interest. This allows an elderly patient, for

example, to save a great deal of time by just focusing

on the specific type of information he/she has

requested (condition in this case).

Figure 7: First results of search for hepatitis keyword with

Condition and Code sub-filters.

Moreover, FACILE provides some information

directly in the response page (e.g., Specialty:

Gastroenterologic and Name: Cirrhosis for the

Condition) that can be used for further investigation

if of interest. Also the code identifier (e.g., CUI in the

UMLS coding system) and code value (e.g.,

C0019167 that corresponds to Hepatitis B e

Antigens), can be used to have a unique reference of

the information that is being read and that can be used

for further discussion with a doctor or in a hospital.

Notice that we plan to implement the translation of

the code value in its corresponding term so to add this

information directly in the response window.

If the user enables the “Show Quality

Information?” switch button, the quality information,

such as “Date published” or “Last reviewed”, will be

shown (Fig. 8) and the user will have the possibility

to choose, for example, the most recent information.

If the author or publisher information are present, the

user will have the possibility to analyse the

information only if he/she trusts the source it is

coming from.

Figure 8: First results of search for hepatitis keyword with

Quality filter activated.

If the user wants to find pages that match his/her

medical literature level, he/she will check the

“Audience” sub-filter. In this case the target audience

of the page will be shown (whenever present - Fig. 9)

and the user will be able to select the most suitable

pages. For example, in the case of Fig. 9, an elderly

patient would not analyse the pages whose audience

is “clinician” so avoiding to waste time with Web

content that is too difficult to understand.

Notice that in (Alfano et al., 2019c) we have

evaluated the language familiarity of Web pages

targeted to different audience types. This has been

done by computing the “term familiarity index” of a

word (i.e., number of results provided by the Google

search engine, Kloehn, et al., 2018; Leroy, et al.,

2012) and then computing the language familiarity of

a Web page as the average of the term familiarity

indexes of its words. The results clearly show that, on

average, the Web pages targeted to patients have a

much higher language familiarity, and thus a simpler

terminology than the Web pages targeted to clinicians

or medical researchers.

Figure 9: First results of search for hepatitis keyword with

Audience sub-filter activated.

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

212

For sake of completeness of all the filtering

possibilities, we can finally assume that a medical

expert is looking for information on hepatitis. In this

case, given his/her skills, he/she will probably search

for scholarly articles obtaining a result such as the one

reported in Fig. 10 that provides more technical

information.

Figure 10: First results of search for hepatitis keyword with

“Scholarly article” filter activated.

5 DISCUSSION

Although, the development of FACILE is still at

prototypal stage and more experiments are

undoubtedly needed, its principles and practical use

show how FACILE complies with the three-level

communication model presented in Section 2

allowing a non-expert user (e.g., an elderly patient) to

specify his/her requirements in a simple language,

translating into structured data elements for retrieving

health information from the Web, and providing the

user with the “right” amount of reliable and simple

information that he/she can easily understand and

employ in his/her process of empowerment and in

subsequent communication/interaction with medical

professionals. The compliance of Facile with the

three levels of the communication model can be

further analysed as follows:

1. Syntactic-Technical: FACILE presents the

same retrieval capabilities as a generic search

engine and, as such, it allows the user to search

for health information on the Web (although it

restrains the search to the semantic Web) and

returns the requested information as any generic

search engine does.

2. Semantic-Meaning: The translation capability

of FACILE (mapping model) allows the user to

specify his/her requirements in simple terms.

FACILE translates the user requirements into

schema.org elements in order to extract the

appropriate information from the Web

(communication phase: from user to FACILE).

Moreover, the ability of FACILE, to retrieve

Web pages that present different language

complexity levels, allows the user to choose the

pages whose language can be easily understood

(communication phase: from FACILE to user).

3. Pragmatic-Effectiveness: The response

presented by FACILE has a pragmatic impact on

the user (mainly a non-expert one) in terms of

focused and reliable Web results (by avoiding to

spend time analysing the large amount of results

that a generic search engine provides), the

specific information provided in the response

page, and the language simplicity. The

consequence is that a user is, overall, greatly

facilitated in finding, understanding and using

health/medical information on the Web and then

in his/her empowerment process. This, among

others, facilitates the comprehension of his/her

medical conditions and increases his/her ability

to communicate with medical professionals and

make informed decisions.

Notice that the process of finding the “right”

information may be iterative. Although, FACILE has

the objective of immediately providing the user with

the desired information, its flexibility and easiness of

use allows the user to perform further searches when

needed in order to get further information. For

example, first he/she might need to understand a

medical condition/disease and then find a therapy and

the medicines for it. The user might also want to

remove the filtering information, at some stage, in

order to have the possibility of analysing more pages

at the same time. Having already analysed the focused

information (and related Web pages), he/she will

have the ability and confidence to expand his/her

exploration by quickly analysing the remaining

information (or part of it). Overall, FACILE provides

the user with the possibility of filtering and re-ranking

the Web results according to his/her specific

requirements but it leaves the user fully in charge of

his/her navigational path on the Web. In this way, the

user can freely and simply choose what he/she needs

in terms of health/medical information, in any

moment, so to achieve his/her empowerment

objectives and act upon them. Notice that, although,

most of the time, users search for health information

on the Web before or after having consulted a medical

professional as a doctor, the ideal case would see a

doctor accompanying the patient in his/her

navigational path on the Web so to help him/her to

find the most suitable and reliable medical

information. Of course, this is not always possible,

due to time constraints. Nevertheless, we are working

with medical professionals (doctors and nurses) to

Tailored Retrieval of Health Information from the Web for Facilitating Communication and Empowerment of Elderly People

213

understand (and implement as much as possible) their

advices to patients who navigate the Web in search of

“good” health/medical information.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this work, we have presented a “unified” three-

levels communication model that allows a full

interaction of a patient/citizen with both a machine

(e.g., search engine) and another human (e.g., medical

professional). We have shown as a generic search

engine only reaches the first level of the

communication model because it does not allow the

user to specify his/her requirements and thus it does

not provide focused information that the user can

easily and promptly understand and use.

We have then presented FACILE, a custom search

engine, that allows a user to specify his/her

information requirements in a simple way and maps

them to schema.org structured elements. It then

retrieves the “right” and simple Web content without

overwhelming the user. This positively affects his/her

understanding and use and, as a consequence, the

empowerment process.

The principles and first experimental results are

satisfying and show FACILE potentialities even

though, the used dataset (created with the 2018

structured data of Web Data Commons) has proven,

sometimes, too limited in terms of provided results.

Thus, we are in the process of adding the 2019 dataset

(that has become available in the meantime) as well

as the 2017 and 2016 datasets (the various datasets

present some differences), so to have more data to

experiment with and, hopefully, more results.

A deeper analysis also needs to be executed in order

to better understand the mapping between the user

requirements and the schema.org elements, as in the

case of the information quality. Furthermore,

although FACILE is simple and intuitive, we are in

the process of running some tests with elderly people

to evaluate their engagement level in using FACILE

and understand what are the aspects that need to be

improved. An evaluation of the reached

empowerment level is also important and we are in

the process of running some experiments with

patients with multimorbidity. After using FACILE,

the reached health literacy and empowerment levels

will be measured.

As a future work, we want to further develop the

unified communication model for improving the

human-to-human and human-to-machine

communication processes that underlie patient

empowerment. For example, we plan to improve the

communication between patients and medical

professionals by translating the medical terms,

retrieved by FACILE, in lay terms (Alfano et al.,

2020; Alfano et al., 2018; Alfano et al., 2015).

Moreover, we want to create a visual framework

(Alfano et al., 2016) that uses the retrieving

capabilities of FACILE and allows easy creation of

advanced health services for elderly people, such as

virtual assistants, thus facilitating the human-to-

machine communication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by the European

Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation

programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant

agreement No 754489 and by Science Foundation

Ireland grant 13/RC/2094 with a co-fund of the

European Regional Development Fund through the

Southern & Eastern Regional Operational

Programme to Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland

Research Centre for Software, www.lero.ie.

We would like to thank Allan Gomes, of the

Graduate School of Engineering of the University of

Nantes, for his notable support in the technical

development of the FACILE custom engine.

REFERENCES

Alfano, M., Lenzitti, B., Lo Bosco, G., Muriana, C., Piazza,

T., Vizzini, G., 2020. Design, Development and

Validation of a System for Automatic Help to Medical

Text Understanding. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, Elsevier. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.ijmedinf.2020.104109

Alfano, M., Lenzitti, B., Taibi, D., Helfert, M., 2019a.

Provision of Tailored Health Information for Patient

Empowerment: An Initial Study. In Proceedings of the

20th International Conference on Computer Systems

and Technologies (CompSysTech ’19). Association for

Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 213–

220. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3345252.3345301.

Alfano M., Lenzitti B., Taibi D., Helfert M., 2019b.

ULearn: Personalized Medical Learning on the Web for

Patient Empowerment. In: Herzog M., Kubincová Z.,

Han P., Temperini M. (eds) Advances in Web-Based

Learning – ICWL 2019. ICWL 2019. Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, vol 11841. Springer, Cham.

Alfano, M., Lenzitti, B., Taibi, D., Helfert M., 2019c.

Facilitating access to health Web pages with different

language complexity levels. Proc. of the 5th Inter.

Conference on Information and Communication

Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE

2019), 2-4 May 2019, Heraklion-Crete.

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

214

Alfano, M., Lenzitti, B., Lo Bosco, G., and Taibi, D., 2018.

Development and Practical Use of a Medical

Vocabulary-Thesaurus-Dictionary for Patient

Empowerment. Proc. of ACM International Conference

on Computer Systems and Technologies

(CompSysTech’18), Ruse.

Alfano, M., Lenzitti, B., Lo Bosco, G., and Taibi, D., 2016.

A Framework for Opening Data and Creating

Advanced Services in the Health and Social Fields.

Proc. of ACM International Conference on Computer

Systems and Technologies (CompSysTech’16),

Palermo.

Alfano, M., Lenzitti, B., Lo Bosco, G., and Perticone, V.,

2015. An Automatic System for Helping Health

Consumers to Understand Medical Texts, Proc. of

HEALTHINF 2015, Lisbon, pp. 622-627.

Akerkar, S., & Bichile, L., 2004. Health Information on the

Internet: Patient Empowerment or Patient Deceit?

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, 58(8). Pp. 321-

326.

Banna, S., Hasan, H. & Dawson, P., 2016. Understanding

the diversity of user requirements for interactive online

health services. International Journal of Healthcare

Technology and Management, 15(3).

Bodolica, V., & Spraggon, M., 2019. Toward patient-

centered care and inclusive health-care governance: a

review of patient empowerment in the UAE. Public

Health, 169(971), 114–124.

Bravo, P., Edwards, A., Barr, P. J., Scholl, I., Elwyn, G., &

McAllister, M., 2015. Conceptualising patient

empowerment: A mixed methods study. BMC Health

Services Research, 15(1), 1–14.

Carlile, P., 2004. Transferring, Translating and

Transforming: An Integrative Framework for

Managing Knowledge Across Boundaries, Organ-

ization Science, 15(5), pp. 555-68.

Cerezo, P. G., Juvé-Udina, M. E., Delgado-Hito, P., 2016.

Concepts and measures of patient empowerment: A

comprehensive review. Revista Da Escola de

Enfermagem.

Cherry, C. (1966). On human communication: a review, a

survey, and a criticism. Cambridge, Mass, M.I.T. Press.

Dietze S., Taibi D., Yu R., Barker P., d'Aquin M., 2017.

Analysing and Improving Embedded Markup of

Learning Resources on the Web. Proc. of the 26th

International Conference on World Wide Web

Companion (WWW '17 Companion), Switzerland, 283-

292.

European Health Parliament. 2017. PATIENT

EMPOWERMENT AND CENTREDNESS.

Fumagalli, L. P., Radaelli, G., Lettieri, E., Bertele’, P.,

Masella, C., 2015. Patient Empowerment and its

neighbours: Clarifying the boundaries and their mutual

relationships. Health Policy. 119(3), 384–394.

Hahn, L. K. & Paynton, S. T. 2014. Survey of

Communication Study. https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/

Survey_of_Communication_Study.

Health promotion glossary. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 1998.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2010. Encuesta sobre

Equipamiento y Uso de Tecnologías de la Información

y Comunicación en los hogares.

Johnson, F.C., Klare, G.R. 1961. General Models of

Communication Research: A Survey of the

Developments of a Decade, Journal of Communication,

Volume 11, Issue 1, March 1961, Pages 13–26.

Keselman, A., Logan, R., Smith, C. A., Leroy, G., & Zeng-

Treitler, Q., 2008. Developing informatics tools and

strategies for consumer-centered health

communication. Journal of the American Medical

Informatics Association : JAMIA, 15(4), 473–483.

Kloehn, N. et al., 2018. Improving consumer understanding

of medical text: Development and validation of a new

subsimplify algorithm to automatically generate term

explanations in English and Spanish. Journal of

Medical Internet Research, 20(8).

Leroy, G. et al., 2012. Improving perceived and actual text

difficulty for health information consumers using semi-

automated methods. AMIA Annual Symposium

Proceedings. pp.522–31.

Morris, C.W. 1938. Foundations of the theory of signs.

International encyclopedia of unified science, vol. 1,

no. 2. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Meusel, R., Petrovski, P., and Bizer, C. 2014. The

WebDataCommons Microdata, RDFa and Microformat

Dataset Series. Proc. of the 13th International Semantic

Web Conference (ISWC14), Springer-Verlag New

York, USA, 277-292.

Pang, P. C.-I.; Verspoor, K.; Pearce, J.; Chang, S. 2015.

Better Health Explorer: De-signing for Health

Information Seekers. In OzCHI ’15 Proceedings of the

Annual Meeting of the Australian Special Interest

Group for Computer Human Interaction (pp. 588–597).

Pletneva, N., Vargas, A. & Boyer, C., 2011. Requirements

for the general public health search. Khresmoi Public

Deliverable D8.1.1.

Pew Research Center, 2013. Health online 2013,

http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-

2013/.

Pian, W., C.S.G. Khoo, J. Chi. 2017. Automatic

classification of users’ health information need context:

Logistic regression analysis of mouse-click and eye-

tracker data. Journal of Medical Internet Research,

19(12).

Roberts, T. 2017. Searching the Internet for Health

Information: Techniques for Patients to Effectively

Search Both Public and Professional Websites. SLE

Workshop at Hospital for Special Surgery Tips For

Evaluating the Quality of Health, 1–12.

Shannon, C., W. Weaver. 1949. The Mathematical Theory

of Communications. University of Illinois Press,

Urbana, IL.

Smith, T. 2004. Exploring the characteristics of active

health seekers, the thinking behind patient preferences,

and the implications for patient-professional

relationships. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(6),

474–477.

Taibi D., Fetahu B., Dietze S. 2013. Towards integration of

web data into a coherent educational data graph. In

Tailored Retrieval of Health Information from the Web for Facilitating Communication and Empowerment of Elderly People

215

Proc. of the 22nd Int. Conference on World Wide Web

(WWW ’13 Companion). Association for Computing

Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 419–424.

Taylor, H. 2010. HI-Harris-Poll-Cyberchondrics. Harris

Interactive. https://theharrispoll.com/the-latest-harris-

poll-measuring-how-many-people-use-the-internet-to-

look-for-information-about-health-topics-finds-that-

the-numbers-continue-to-increase-the-harris-poll-first-

used-the-word-cyberch/.

UK national statistics, 2010. Statistical bulletin: Internet

Access 2010. Office for National Statistics. 27 Aug

2010.

Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J. B., & Jackson, D. D. 1967.

Pragmatics of human communication: a study of

interactional patterns, pathologies, and paradoxes.

Norton, New York.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2016. Framework on

integrated, people-centred health services: Report by

the Secretariat. World Health Assembly, (A69/39), 1–

12.

World Health Organization (WHO). 1998. Health

promotion glossary. https://www.who.int/

healthpromotion/about/HPR%20Glossary%201998.pd

f.

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

216