Urban Consumption Patterns: OpenStreetMap Quality for Social

Science Research

Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi

1a

1

, Gavin McArdle

1b

2

and Andrea Ballatore

2c

3

1

School of Computer Science and CeADAR, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin, Ireland

2

Department of Geography, Birkbeck, University of London, Malet Street, London, U.K.

Keywords: Consumption Inequality, OpenStreetMap (OSM), Data Quality, London.

Abstract: Citizen consumption refers to the goods and services which citizens utilise. This includes time spent on leisure

and cultural activities as well as the consumption of necessary and luxury goods and services. The spatial

dimension of consumption inequality can show the underlying urban spatial structure and processes of a city.

Usually, the main barrier to effectively measuring consumption is the availability and accessibility of spatial

data. While the main body of the literature utilises official, government data, such data is not always available,

up-to-date or can be costly to acquire. In this paper, we discuss the potential of Volunteered Geographic

Information (VGI) as a source of spatial data for determining consumption inequality. To this end, we

compared OpenStreetMap (OSM) data, that can be used as proxies for consumption inequality, with official

data in the area of Greater London. The results show that OSM is currently inadequate for studying the spatial

dimension of consumption. It is our view that while VGI is appropriate for tasks such as routing and

navigation, it also has the potential to add value to social science studies in the future.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cities are centres of consumption due to the size of

population and density (Glaeser et al. 2001) but

access to consumption spaces is not equal for all

citizens (Mahadevia and Sarkar 2012). While the

focus of the literature on urban inequality is usually

on income inequality, consumption inequality

deserves more attention. Briefly, consumption means

what people consume including what they allocate

time to such as leisure or cultural activities e.g.

cinema and music, luxury goods such as jewellery

and necessary goods such as food and medicine. On

one hand, shopping baskets vary across income

groups in terms of quality and quantity. On the other

hand, from a geographic point of view, it is taken for

granted that the prices of goods and services are

usually not constant in different parts of cities due to

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2576-793X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0613-546X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3477-7654

1

https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables.htm

2

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/

english-indices-of-deprivation-2015

their quality and consumers' ability and willingness to

pay for them.

Although measuring consumption and leisure is

complex due to the multidimensionality of

consumption (Attanasio et al. 2012) such as allocated

time for leisure (Aguiar and Hurst 2007), identifying

where different goods and services are offered in the

city is a common interest of many disciplines such as

urban geography, urban economy, and sociology (Cai

et al. 2010). There are different data sources for

measuring consumption, such as Consumer

Expenditure Surveys

1

4

by the US Bureau of Labor

Statistics which provides data on expenditure,

income, and demographic characteristics of

consumers but this survey does not cover all

components of urban utilities such as leisure. Even

the Index of Multiple Deprivation

2

5

in the UK which

covers income, employment, health deprivation and

disability, education, skills and training, barriers to

278

Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., McArdle, G. and Ballatore, A.

Urban Consumption Patterns: OpenStreetMap Quality for Social Science Research.

DOI: 10.5220/0009576302780285

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management (GISTAM 2020), pages 278-285

ISBN: 978-989-758-425-1

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

housing and services, crime and living environment

does not include consumption and leisure data. Other

efforts are usually limited to mapping energy

consumption and water consumption regardless of the

sociospatial setting of the city.

Measuring consumption and leisure inequality

(Attanasio and Pistaferri 2016), and mapping patterns

of consumption inequality of goods e.g. the

geographical distribution of fast food outlets and

supermarkets, pharmacies, and cultural centres of a

city draw a different picture from income inequality

(Attanasio and Pistaferri 2016). Many researchers

believe Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI)

can be an effective alternative to official data

(Goodchild 2007) or can enrich or complement

official data (Antoniou 2011). Among VGI platforms,

OpenStreetMap (OSM)

3

6 has been tested in various

domains such as land use classification (Pfoser 2013),

road network analysis (Zhang and Malczewski 2017),

and disaster management (Zook et al. 2010). While

many previous studies seem promising of the high

potentials of OSM applications, there is little research

on the extraction of locational insight from user-

generated data (Shelton et al. 2015) to investigate

spatial inequality, especially the spatial dimension of

consumption inequality. This is not surprising since,

OSM was not intended for this purpose, yet we seek

to understand if it is suitable for this type of study.

The focus of the literature is on different metrics

of accuracy related to OSM data, but mainly on the

road network and landmarks (Fan et al. 2014; Graser

et al. 2014). The aim of this paper is to examine the

question as to whether OSM data can be used as an

alternative to official data to measure or map spatial

variation of consumption inequality in goods and

urban amenities (Fraser et al. 2010; Dai and Wang

2011). The three main contributions of this paper are:

Assessing completeness, accuracy, and usefulness

of OSM data layers to study consumption

inequality in London.

Testing OSM data in mapping the spatial

dimension of consumption inequality.

Highlighting some of the limitations of using

OSM data in urban studies.

2 BACKGROUND

Crawford describes how “the ethos of consumption

has penetrated every sphere of our lives…[and]

increasingly constructs the way we see the world”

3

https://www.openstreetmap.org

(Crawford 1992, p. 11). Moreover, as Crew and Lowe

argue, “retailing and consumption create and recreate

place-specific” (Crewe and Lowe 1995, p. 1878).

Similarly, Functional Utility can help us to

understand the preferences of individuals for different

goods and services. Simply put, individuals buy the

most important goods and services of their necessities

based on their needs and ability to pay. (Currid‐

Halkett et al. 2019) classified consumption into three

frameworks from an economic geography

perspective, 1. commodification of cultures 2. high-

end luxurious 3. amenities. In this research, we

investigate the potential usage of OSM data to map

the spatial dimension of these main categories of

consumption in the city. The first one represents

cultural centres such as cinemas and theatres. The

second one can be viewed as conspicuous goods

(Veblen or luxury goods), and the last one as

necessary goods for life (Currid‐Halkett et al. 2019).

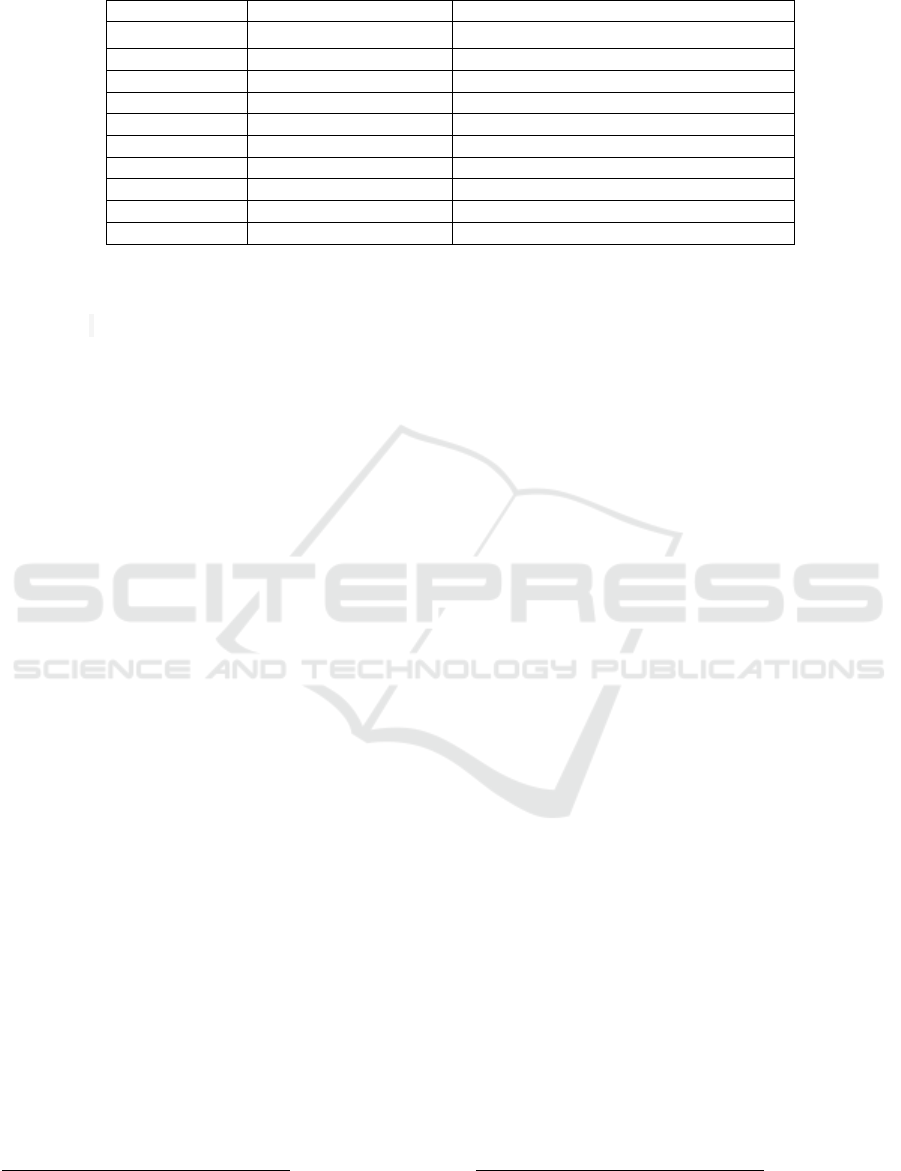

Table 1 shows which OSM tags may be used to

study and map consumption inequality in the city. It

also identifies why the selected tags are proxies of

consumption inequality based on relevant references

to the literature. For example, from a welfare point of

view, consumption inequality of basic necessities,

especially food is very important (Attanasio and

Pistaferri 2016). Food, as one of the basic needs of

human life, is a proxy for both nutrition and leisure

(Mair et al. 2008), but fast-food is energy-dense,

nutrient-poor and can cause obesity (Bowman et al.

2004). Fashion is a specific good that shows where

local identity and global drivers are united (Crewe

and Lowe 1996) and it is a cultural signifier

(McRobbie 1994) and is classified as Veblen goods.

Similarly, a beauty salon belongs to this class.

Furthermore, the swimming pool layer in OSM has

the potential to map the difference between rich and

poor neighbourhoods (Stephens 1996).

VGI has attractive characteristics such as free use

for users and researchers. During the last decade, a

plethora of research has been done using this type of

data (Longueville et al. 2010). The huge range of

applications and potential of VGI opens new horizons

for socioeconomic research and applications to

overcome data limitations and availability (Sun and

Du 2017). OSM, a prominent example of VGI,

attracts much attention, especially where there is no

validated or official data (Moomen et al. 2019). OSM

is available under an Open Database License

4

7, and

users can use, edit and share the maps without

copyright permission.

Recent

growing usage of OSM in different

4

https://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/summary/

Urban Consumption Patterns: OpenStreetMap Quality for Social Science Research

279

Table 1: List of selected OSM Tags and layers.

Name Prox

y

/Descri

p

tion References

Fast food Malnutrition/Health (Burns and Inglis 2007; Mair et al. 2008)

Beaut

y

Salon Veblen

g

oo

d

(

Kwate et al. 2009

)

Garden Leisure

/

Health

(

Chen and Jim 2008; Lou

g

hran 2014

)

,

Swimming pool Leisure

/

Health (Stephens 1996; Salvati et al. 2016)

Cinema Entertainment

/

Culture (Shiel and Fitzmaurice 2001)

Pharmac

y

Health (Clark et al. 2012; Todd et al. 2014)

Librar

y

Entertainment

/

Culture

(

Calcuttawala 2004; Park 2012

)

,

Banks Access to finance

(

Liu et al. 2015

)

Baker

y

Food/ Health/Nutrition

(

Dai and Wan

g

2011

)

Restau

r

ant Leisure

/

Health/ Foo

d

(Mehta and Chang 2008)

domains

of socioeconomic and health research

includes the spatial availability of alcohol (Bright et

al. 2018), social activity of the population

(Putrenko 2017), and retail tobacco exposure

(Rodriguez et al. 2013).

The literature on consumption (inequality) is

usually based on official data and is concentrated on

the consumption of energy (Pereira and Assis 2013;

Souza et al. 2009) or water (Panagopoulos et al. 2012;

Vandecasteele et al. 2014). Usually, an important

driver in sociospatial studies is availability and access

to valid spatial data. Official data are not always up-

to-date and free to access for researchers. This

prompts the question in this paper regarding the

possibility of using OSM data to map consumption

inequality in the city as an alternative to official data.

To achieve this, we need to assess the veracity of

OSM data for this purpose. Different guidelines and

measures have been suggested to assess data quality

(Batini et al. 2009). Each method usually suggests

different metrics for different aspects of data quality.

For spatial data, seven key metrics are as follows

(Guptill and Morrison 1995; Shi et al. 2002; McArdle

and Kitchin 2016).

1. Lineage: the history of data.

2. Positional Accuracy: absolute and relative position.

3. Attribute Accuracy: the accuracy of quantitative

and qualitative data.

4. Completeness: to what extent spatial and attribute

data are complete, including geographical coverage

of spatial data (maps).

5. Logical Consistency: trustiness or dependability of

data.

6. Semantic Accuracy: consistency and persistency of

classes of objects.

7. Temporal Data: observation date, the validity of

time and type of update.

5

http://download.geofabrik.de/europe/great-

britain/england/greater-london.html

Although all measures are important in OSM

assessment (Fan et al. 2014; Ballatore and Zipf 2015),

based on our theoretical framework and the aims of

our research, we gave priority to the completeness of

data because it is a significant metric to study the

spatial dimension of inequality research. It is our

position that without a minimum acceptable degree of

completeness of data, it is not possible to measure any

type of (spatial) inequality in the city. McArdle and

Kitchin describe completeness as the degree to which

spatial and attribute data are included or omitted from

the database. It also describes how the sample is

derived from the full population and presents the

spatial boundaries of the data (McArdle and Kitchin

2016).

3 CASE STUDY & DATA

The case study is Greater London. London is a

thoroughly studied global city that is an ideal and

unique place to assess the usefulness and

completeness of OSM urban data. Researchers agree

that OSM data for London are extremely rich and so

it is an ideal case study to assess the best-case

completeness of OSM data for urban sociospatial

research (Ballatore and Sabbata 2018). OSM Shape

files were collected through two methods using the

GeoFabrik

5

8

website and the QGIS plugin

6

9 tool, for the

Greater London area in November 2019.

4 RESULTS & DISCUSSION

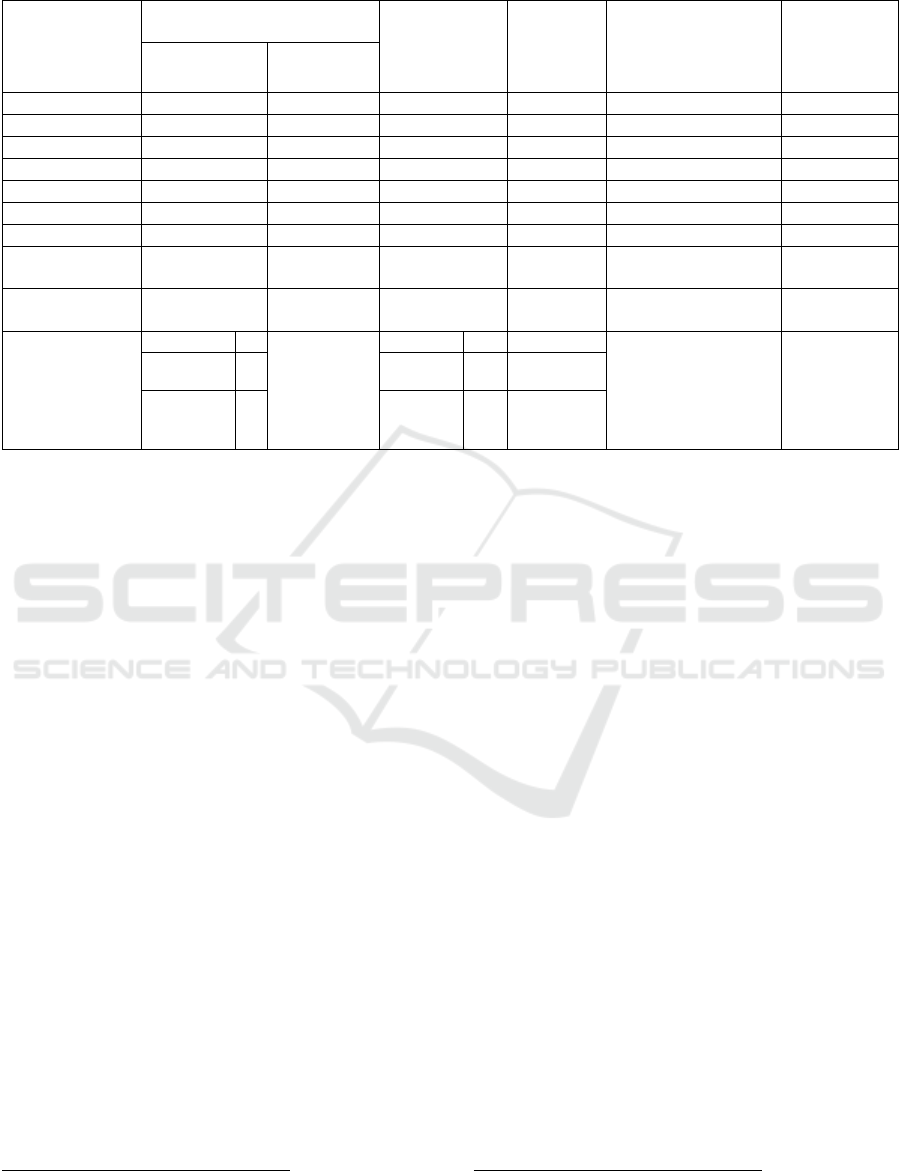

Table 2 shows the difference between the number of

entities of each layer in the official data and OSM data

that

we selected to measure consumption inequality.

6

https://plugins.qgis.org/plugins/QuickOSM/

GISTAM 2020 - 6th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

280

Table 2: Comparison between OSM and official data sources.

OSM Tag Download Source and Number

of entities

Official

Statistics

Date Reference Format

geofabrik.de

(tag=amenity)

QuickOSM

(tag=class)

Fast foo

d

2398 2400 8662 June 2016 gov.u

k

Georef

/

CSV

Swimming pool 13 15 196 Oct 2008 london.gov.uk Report

Cinema 69 69 116 May 2019 data.london.gov.u

k

Georef

/

CSV

Library 169 169 342 Dec 2019 data.london.gov.uk GeoPackage

7

10

Pharmac

y

816 815 1839 Se

p

2019 ordnancesurve

y

.co.u

k

Georef/txt

Theatre 92 80 118 Jan 2019 data.london.gov.uk GeoPackage

Pub 2211 Na 4098 Jan 2019 data.london.

g

ov.u

k

GeoPacka

g

e

Museum and

Public galler

y

Na 86 163 Jan 2019 data.london.gov.uk GeoPackage

Jewelry Design Na 288 320 Nov 2018 data.london.gov.uk GeoPackage

Music

Venue

4

Venues

797 March 2018 data.london.gov.uk GeoPackage

School

4

Rehearsal

Studio

79 June 2019

Instrument

2

Recording

Studio

71 June 2019

All layers of OSM present a lower number of points

compared

to official data although official data is

usually updated slowly and scarcely. Most official

point

layer data were downloaded from the

LondonDatastore

8

11. To assess the impact of utilising

OSM data, typical spatial analysis approaches used to

identify the spatial aspects of consumption were

applied to the OSM and official data. Figure 1

presents, (a) the number of OSM data, (b) number of

official data, (c) Getis Ordi Gi*(Getis and Ord 2010)

of OSM, and (d) Getis Ordi Gi* of official data

respectively for 1. cinema as a cultural centre, 2.

jewellery shops as a provider of luxury good, and 3.

pharmacy as a place to provide basic necessary goods

in a 1000-meter hexagonal gird of the Greater London

Area. Getis Ordi Gi* (Z Score) shows the hotspots

and coldspots of selected layers on each map. Figure

1 shows how three selected layers including cinemas

(cultural consumption), jewellery shops (Veblen

goods), and pharmacies (necessary goods) are

distributed in both OSM and official data.

Both datasets show a concentration of data points

in the city centre. It shows that editors and contributors

in OSM are more focused on the centre of London

where the population activities and consumption

spaces are concentrated while other areas are ignored.

In other words, there is an inconsistency between the

geographical coverage of OSM and official data. This

means that OSM data are not representative of the

7

https://www.geopackage.org/

ground truth data. All Getis indexes (Z Score) also

illustrate a sharp gap between OSM and the official

dataset. For example, the maps in Figure 3c and 3d

show that hotspots and coldspots of pharmacy have

different patterns of data concentration and richness.

These types of visualisation were selected because they

can show the difference between point layers of official

and OSM datasets for this social science study.

The

analysis has shown the gaps in the OSM data and

highlights the challenges of using OSM data for a study

on consumption and inequality. Each dataset would

yield different results. The gaps may relate to the

semantic completeness of map features. Semantic

information describes the function or meaning of a map

feature such as its name or type. In many cases, the

spatial information is available but the description of

the spatial feature which is essential for sociospatial

research is absent and leads to an inability to classify

the feature type which impacts completeness and

veracity (Iddianozie and McArdle 2019).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Data collection is costly and time consuming, and

permission to use or license the data is a barrier in

providing the necessary data for research. Emerging

VGI in general and in particular the OSM platform

are

considered as tools to overcome the data barrier

8

https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/statistical-gis-

boundary-files-london

Urban Consumption Patterns: OpenStreetMap Quality for Social Science Research

281

1. Cinema (Cultural Centre) 2. Jewellery (Veblen Good) 3. Pharmacy (Necessary Good)

a. Number in OSM

b.Number of Official Data

c.Getis Ordi Gi* of OSM

d.Getis Ordi Gi* of Offcial Data

Figure 1: Spatial Coverages and Patterns of Cinema, Jewelry Shops, and Pharmacy in OSM and Official Dataset. (Figure a)

Intensity of red color shows the number of points in each hexagon (Figure a and Figure b). Dark red color shows hotspots

and dark blue is coldstops (Figure c and Figure d) or Getis Ordi Gi* based on Z Score.

and limitation. OSM provides easy access to spatial

data for citizens, policy designers, urban mangers,

and researchers in some domains such as tracking and

road mapping. However, at present the veracity of

OSM data is insufficient for mapping underlying

sociospatial patterns.

Other studies have corroborated the inadequacy of

OSM in other research areas (Muzaffar et al. 2017).

In addition, we have seen in this paper that OSM data

and tags are not consistent across different

downloading methods. This issue makes OSM less

useable in urban socioeconomic research especially

for researchers with less technical skills. This

research raises these critical questions:

1. Why are some layers of OSM (especially layers

which were assessed in this paper) not complete?

How can the OSM mapping community be supported

to address this type of completeness?

2. Are there any relationships between the

completeness of OSM data and the underlying

socioeconomic process? Or in other words, can we

use spatial patterns of richness/incompleteness of

OSM data as a proxy for urban spatial inequality

especially (spatial) digital divide in the city?

3.

Will OSM find its position in the future for

urbansocioeconomic research comparing to

authoritative data sources considering the past and

GISTAM 2020 - 6th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

282

current trends of enriching? Or How can we deal with

this problem?

It is not our intention to be negative towards OSM.

Afterall, it is not the remit of OSM to provide data for

the type of projects discussed in this paper, instead we

wish to highlight the potential of OSM as tool for use

within the social sciences. We have highlighted some

of the current shortcomings of OSM for this purpose.

A partial solution might be technical, but there are

other underlying cultural and socioeconomic factors

in OSM production and consumption that have

potential for multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary

research (Ballatore and Sabbata 2020). We will

explore these in future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi is a Marie Skłodowska-

Curie Career-FIT Fellow at UCD School of Computer

Science, CeADAR (Ireland’s National Centre for

Applied Data Analytics). Career-FIT has received

funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020

research and innovation programme under the Marie

Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 713654. The

Ordnance Survey Points of Interest data is licensed to

Birkbeck, University of London.

REFERENCES

Aguiar, M.; Hurst, E. (2007): Measuring Trends in Leisure:

The Allocation of Time Over Five Decades. In The

Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (3), pp. 969–1006.

DOI: 10.1162/qjec.122.3.969.

Antoniou, V. (2011): User generated spatial content: an

analysis of the phenomenon and its challenges for

mapping agencies. UCL (University College London).

Attanasio, Orazio; Hurst, Erik; Pistaferri, Luigi (2012): The

Evolution of Income, Consumption, and Leisure

Inequality in The US, 1980-2010. Cambridge, MA.

Attanasio, Orazio P.; Pistaferri, Luigi (2016): Consumption

Inequality. In Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (2),

pp. 3–28. DOI: 10.1257/jep.30.2.3.

Ballatore, Andrea; Sabbata, Stefano de (2018): Charting the

Geographies of Crowdsourced Information in Greater

London. In Ali Mansourian, Petter Pilesjö, Lars Harrie,

Ron van Lammeren (Eds.): Geospatial Technologies

for All, vol. 64. Cham: Springer International

Publishing (Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and

Cartography), pp. 149–168.

Ballatore, Andrea; Sabbata, Stefano de (2020): Los Angeles

as a digital place: The geographies of user‐generated

content. In Transactions in GIS 64 (1), p. 309. DOI:

10.1111/tgis.12600.

Ballatore, Andrea; Zipf, Alexander (2015): A Conceptual

Quality Framework for Volunteered Geographic

Information. In Sara Irina Fabrikant, Martin Raubal,

Michela Bertolotto, Clare Davies, Scott Freundschuh,

Scott Bell (Eds.): Spatial Information Theory. Cham,

2015: Springer International Publishing, pp. 89–107.

Batini, Carlo; Cappiello, Cinzia; Francalanci, Chiara;

Maurino, Andrea (2009): Methodologies for data

quality assessment and improvement. In ACM Comput.

Surv. 41 (3), pp. 1–52. DOI:

10.1145/1541880.1541883.

Bowman, Shanthy A.; Gortmaker, Steven L.; Ebbeling,

Cara B.; Pereira, Mark A.; Ludwig, David S. (2004):

Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and

diet quality among children in a national household

survey. In Pediatrics 113 (1 Pt 1), pp. 112–118. DOI:

10.1542/peds.113.1.112.

Bright, Jonathan; Sabbata, Stefano de; Lee, Sumin; Ganesh,

Bharath; Humphreys, David K. (2018): OpenStreetMap

data for alcohol research: Reliability assessment and

quality indicators. In Health & place 50, pp. 130–136.

DOI: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.01.009.

Burns, C. M.; Inglis, A. D. (2007): Measuring food access

in Melbourne: access to healthy and fast foods by car,

bus and foot in an urban municipality in Melbourne. In

Health & place 13 (4), pp. 877–885. DOI:

10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.02.005.

Cai, Hongbin; Chen, Yuyu; Zhou, Li-An (2010): Income

and consumption inequality in urban China: 1992–

2003. In Economic Development and Cultural Change

58 (3), pp. 385–413.

Calcuttawala, Zohra (2004): Knowledge stores: The spatial

dynamics of public library accessibility and

consumption in Calcutta. University of Cincinnati.

Chen, Wendy Y.; Jim, C. Y. (2008): Cost–benefit analysis

of the leisure value of urban greening in the new

Chinese city of Zhuhai. In Cities 25 (5), pp. 298–309.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2008.06.002.

Clark, Robyn A.; Coffee, Neil; Turner, Dorothy; Eckert,

Kerena A.; van Gaans, Deborah; Wilkinson, David et

al. (2012): Application of geographic modeling

techniques to quantify spatial access to health services

before and after an acute cardiac event: the Cardiac

Accessibility and Remoteness Index for Australia

(ARIA) project. In Circulation 125 (16), pp. 2006–

2014. DOI:

10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.083394.

Crawford, Margaret (1992): The world in a shopping mall.

In The city cultures Reader.

Crewe, Louise; Lowe, Michelle (1995): Gap on the map?

Towards a geography of consumption and identity. In

Environment and Planning A 27 (12), pp. 1877–1898.

Crewe, Louise; Lowe, Michelle (1996): United colours?

Globalization and localization tendencies in fashion

retailing. In Retailing, Consumption and Capital.

Towards the New Retail Geography. London:

Longman, pp. 271–283.

Currid‐Halkett, Elizabeth; Lee, Hyojung; Painter, Gary D.

(2019): Veblen goods and urban distinction: The

Urban Consumption Patterns: OpenStreetMap Quality for Social Science Research

283

economic geography of conspicuous consumption. In

Journal of Regional Science 59 (1), pp. 83–117.

Dai, Dajun; Wang, Fahui (2011): Geographic disparities in

accessibility to food stores in southwest Mississippi. In

Environ. Plann. B 38 (4), pp. 659–677. DOI:

10.1068/b36149.

Fan, Hongchao; Zipf, Alexander; Fu, Qing; Neis, Pascal

(2014): Quality assessment for building footprints data

on OpenStreetMap. In International Journal of

Geographical Information Science 28 (4), pp. 700–719.

DOI: 10.1080/13658816.2013.867495.

Fraser, Lorna K.; Edwards, Kimberly L.; Cade, Janet;

Clarke, Graham P. (2010): The geography of fast food

outlets: a review. In International journal of

environmental research and public health 7 (5),

pp. 2290–2308.

Getis, Arthur; Ord, J. Keith (2010): The Analysis of Spatial

Association by Use of Distance Statistics. In Luc

Anselin, Sergio J. Rey (Eds.): Perspectives on Spatial

Data Analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin

Heidelberg, pp. 127–145. Available online at

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-01976-0_10.

Glaeser, Edward L.; Kolko, Jed; Saiz, Albert (2001):

Consumer city. In Journal of Economic Geography 1

(1), pp. 27–50. DOI: 10.1093/jeg/1.1.27.

Goodchild, Michael F. (2007): Citizens as sensors: the

world of volunteered geography. In GeoJournal 69 (4),

pp. 211–221.

Graser, Anita; Straub, Markus; Dragaschnig, Melitta

(2014): Is OSM Good Enough for Vehicle Routing? A

Study Comparing Street Networks in Vienna. In Georg

Gärtner, Haosheng Huang (Eds.): Progress in location-

based services 2014, vol. 22. Cham: Springer (Lecture

Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography, 1863-2246),

pp. 3–17.

Guptill, Stephen C.; Morrison, Joel (1995): Elements of

spatial data quality. Kidlington: Elsevier Science.

Iddianozie, Chidubem; McArdle, Gavin (2019): A transfer

learning paradigm for spatial networks. In Chih-Cheng

Hung, George A. Papadopoulos (Eds.): The 34th

Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing.

Limassol, Cyprus, April 8-12, 2019. the 34th

ACM/SIGAPP Symposium. Limassol, Cyprus,

4/8/2019 - 4/12/2019. [New York, New York]:

Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 659–666.

Kwate, Naa Oyo A.; Yau, Chun-Yip; Loh, Ji-Meng;

Williams, Donya (2009): Inequality in obesigenic

environments: fast food density in New York City. In

Health & place 15 (1), pp. 364–373. DOI:

10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.07.003.

Liu, Yafei; Dijst, Martin; Geertman, Stan (2015):

Residential segregation and well-being inequality over

time: A study on the local and migrant elderly people in

Shanghai. In Cities 49, pp. 1–13. DOI:

10.1016/j.cities.2015.06.012.

Longueville, Bertrand De; Luraschi, Gianluca; Smits, Paul;

Peedell, Stephen; Groeve, Tom De (2010): Citizens as

sensors for natural hazards: A VGI integration

workflow. In Geomatica 64 (1), pp. 41–59.

Loughran, Kevin (2014): Parks for profit: The high line,

growth machines, and the uneven development of urban

public spaces. In City & Community 13 (1), pp. 49–68.

Mahadevia, Darshini; Sarkar, Sandip (2012): Handbook of

urban inequalities. In OUP Catalogue.

Mair, Heather; Sumner, Jennifer; Rotteau, Leahora (2008):

The politics of eating: Food practices as critically

reflexive leisure. In Leisure/Loisir 32 (2), pp. 379–405.

DOI: 10.1080/14927713.2008.9651415.

McArdle, Gavin; Kitchin, Rob (2016): Improving the

veracity of open and real-time urban data. In Built

Environment 42 (3), pp. 457–473.

McRobbie, Angela (1994): Postmodernism and popular

culture. London: Routledge.

Mehta, Neil K.; Chang, Virginia W. (2008): Weight Status

and Restaurant Availability: A Multilevel Analysis. In

American Journal of Preventive Medicine 34 (2),

pp. 127–133. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.031.

Moomen, Abdul-Wadood; Bertolotto, Michela; Lacroix,

Pierre; Jensen, David (2019): Inadequate adaptation of

geospatial information for sustainable mining towards

agenda 2030 sustainable development goals. In Journal

of Cleaner Production 238, p. 117954. DOI:

10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117954.

Muzaffar, Hafiz Muhammad; Tahir, Ali; Ali, Asmat;

Ahmad, Munir; McArdle, Gavin (2017): Quality

Assessment of Volunteered Geographic Information for

Educational Planning. In : Volunteered Geographic

Information and the Future of Geospatial Data: IGI

Global, pp. 76–96.

Panagopoulos, George P.; Bathrellos, George D.;

Skilodimou, Hariklia D.; Martsouka, Faini A. (2012):

Mapping Urban Water Demands Using Multi-Criteria

Analysis and GIS. In Water Resour Manage 26 (5),

pp. 1347–1363. DOI: 10.1007/s11269-011-9962-3.

Park, Sung Jae (2012): Measuring public library

accessibility: A case study using GIS. In Library &

Information Science Research 34 (1), pp. 13–21. DOI:

10.1016/j.lisr.2011.07.007.

Pfoser, Dieter (Ed.) (2013): Proceedings of the Second

ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on

Crowdsourced and Volunteered Geographic

Information. the Second ACM SIGSPATIAL

International Workshop. Orlando, Florida, 11/5/2013 -

11/5/2013. New York, NY: ACM.

Putrenko, Viktor (2017): Data mining of relationship in

crowdsourcing projects and social activities of citizens.

In : 2017 IEEE First Ukraine Conference on Electrical

and Computer Engineering (UKRCON). Conference

proceedings : May 29-June 2, 2017, Kyiv, Ukraine.

2017 IEEE First Ukraine Conference on Electrical and

Computer Engineering (UKRCON). Kiev, 5/29/2017 -

6/2/2017. [Piscataway, New Jersey]: IEEE, pp. 1060–

1065.

Rodriguez, Daniel; Carlos, Heather A.; Adachi-Mejia,

Anna M.; Berke, Ethan M.; Sargent, James (2013):

Retail tobacco exposure: Using geographic analysis to

identify areas with excessively high retail density. In

nicotine & tobacco research 16 (2), pp. 155–165.

GISTAM 2020 - 6th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

284

Salvati, Luca; Ridolfi, Elena; Pujol, David Saurí; Ruiz, Pere

Serra (2016): Latent sprawl, divided Mediterranean

landscapes: urban growth, swimming pools, and the

socio-spatial structure of Athens, Greece. In Urban

Geography 37 (2), pp. 296–312. DOI:

10.1080/02723638.2015.1058115.

Shi, Wenzhong; Goodchild, Michael F.; Fisher, Peter F.

(2002): Spatial data quality. London: Taylor & Francis.

Shiel, Mark; Fitzmaurice, Tony (2001): Cinema and the

city. Film and urban societies in a global context /

edited by Mark Shiel and Tony Fitzmaurice. Oxford:

Blackwell (Studies in urban and social change).

Stephens, Carolyn (1996): Healthy cities or unhealthy

islands? The health and social implications of urban

inequality. In Environment and Urbanization 8 (2),

pp. 9–30. DOI: 10.1177/095624789600800211.

Sun, Yeran; Du, Yunyan (2017): Big data and sustainable

cities: applications of new and emerging forms of

geospatial data in urban studies. In Open geospatial

data, softw. stand. 2 (1), p. 1940. DOI:

10.1186/s40965-017-0037-0.

Todd, Adam; Copeland, Alison; Husband, Andy; Kasim,

Adetayo; Bambra, Clare (2014): The positive pharmacy

care law: an area-level analysis of the relationship

between community pharmacy distribution, urbanity

and social deprivation in England. In BMJ open 4 (8),

e005764. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005764.

Vandecasteele, I.; Bianchi, A.; Batista e Silva, F.; Lavalle,

C.; Batelaan, O. (2014): Mapping current and future

European public water withdrawals and consumption.

In Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18 (2), pp. 407–416. DOI:

10.5194/hess-18-407-2014.

Zhang, Hongyu; Malczewski, Jacek (2017): Accuracy

evaluation of the Canadian OpenStreetMap road

networks. In International Journal of Geospatial and

Environmental Research 5 (2).

Zook, Matthew; Graham, Mark; Shelton, Taylor; Gorman,

Sean (2010): Volunteered Geographic Information and

Crowdsourcing Disaster Relief: A Case Study of the

Haitian Earthquake. In World Medical & Health Policy

2 (2), pp. 6–32. DOI: 10.2202/1948-4682.1069.

Urban Consumption Patterns: OpenStreetMap Quality for Social Science Research

285