Government Digital Service Co-design: Concepts to Collaboration

Tools

Muneer Nusir

College of Computer Engineering and Sciences, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University,

Sa'ad Ibn Mu'adh Street, 11942 Al-kharj, Saudi Arabia

Keywords: Co-design, Design Business Process, e-Government Services, e-Service Design, Key Stakeholders.

Abstract: The inception of digital services is succeeded with the myriad advancements in ICT that aim to support the

growing needs of users and internet-enabled devices. The diversities of these functionalities and digital

services are motivated by the presence of dynamic technologies, delivery channels, and diverse user needs in

an internet-enabled environment. What appropriate instruments could help to support the collaborative design

and create an environment characterized by active knowledge between providers of service and end-users of

the service? The co-design is a well-known approach within the design community that utilizes advanced

ideas and varied instruments of co-design. This study aimed is how to identify unmet requirements for

Government to Citizen (G2C) e-service design and significant ways of achieving the requisite design needs

using a suitable design process? Detailed interviews were undertaken with three groups of stakeholders in

regards to the service design. This study analyses the data collected using an inductive thematic analysis to

analyze qualitative data collected from study participants. This study also explores the patterns resulting from

the G2C e-service design process and further establishes the interconnection between the processes in regards

to fostering the effectiveness and efficiency of the services.

1 INTRODUCTION

e-Government service suppliers should ideally

emphasize on what makes service users gratified in

their daily life and work, reducing centralization

procedures in government agencies and organizations

(Cordella and Tempini, 2015). In contrast to

commercial services, government digital services are

typically developed by internal service providers and

often neglect the service end-user (Axelsson and

Melin, 2007; Bridge, 2012). Therefore, the delivery

of services might be endangered without due concern

of the service users, deficient consideration of their

needs and prospects in the design process (Wu et al.,

2013; Zhao et al., 2008). The consequence of this

challenge is a failure of e-Government projects and a

lack of trust in e-Government services; particularly in

developing countries (Kim et al., 2019; Choudrie et

al., 2009). Limited user involvement throughout the

design process of e-Government services is typical

practice (Anthopoulos et al., 2007; Olphert and

Damodaran, 2007).

Nevertheless, Heeks (2003) acknowledges the

existence of a high failure rate of e-Government

particularly among nations categorized as unindus-

trialized or undeveloped. Further findings reported by

Heeks indicates that at least 35% of the governmental

projects have failed completely, which is coupled with

an estimated 50% failing partially. The figures eclipse

the success of the proposed projects that is only 15%.

The challenge of failing projects has attracted scrutiny

and opposition due to missing trust and credibility

among service providers and consumers of the e-

Government services (Twizeyimana and Andersson,

2019). Besides, among the developing nations, the

mandate of providing eGovernment services is offered

by service providers internally who have a tendency of

neglecting the concerns of those consuming those

services. Most importantly, Wu et al. (2013), and Zhao

et al. (2008) note that service delivery is threatened as

the users are not taken into consideration in terms of

their diverse needs and expectations form the service

framework process.

The challenge of disregarding the users of e-

Government services indicates that providers are

cushioned by the marginal of the services provided

that limits them from meeting the needs of the service

users. Thus, this study aimed to identify unmet

requirements for Government to Citizen (G2C) e-

service design and significant ways of achieving the

Nusir, M.

Government Digital Service Co-design: Concepts to Collaboration Tools.

DOI: 10.5220/0009956900610070

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE 2020) - Volume 3: ICE-B, pages 61-70

ISBN: 978-989-758-447-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

61

requisite design needs using a suitable design process.

This marks the need to bridge the gap differentiating

these two key stakeholders. Therefore, this study

adopted a relatively known ‘co-design approach’ to

enable the government to align a collaborative

relationship between users of services and providers

for the benefit of the citizens (Bridge, 2012). As a

provider of services, the application of this approach

aims to improve the involvement of services in terms

of participating and collaborating activities with

providers of service.

This paper presents a theoretical “design-led”

contribution from a digital service design study (see

figure 4). Co-design is well realized in the design

environment with some innovative and wide-ranging

co-design tools and methods (Zheng et al., 2019). The

paper starts with theoretical government background

literature, service design methodologies and

subsequently leads to the solution space

encompassing co-design techniques.

The main aim of this paper is to identify unmet

requirements for Government to Citizen (G2C) e-

service design and significant ways of achieving the

requisite design needs using a suitable design process.

Accordingly, Sanders and Stappers (2008) expound

on the implications that result from incongruences

between service design requirements and the service

design activities. Some of the mismatches include the

threat of recording decreased benefits from the entire

design process.

The purpose of this paper is to establish the

advantages of co-design approaches present in design

environments that are molded to facilitate the wide-

range activities undertaken by stakeholders. The

activities are hinged on a pledge to be delivered

alongside practical benefits linked to an e-service

design. The next section expounds on numerous

theoretical background literature on e-Government

service. The subsequent section will provide a

discussion on the research methods including the

research phases employed in this paper. The last

section will detail a case study on fieldwork testing.

In terms of the conclusion, this paper will provide a

summative discussion on the significant sections

tackled on the subject of e-Government services.

2 E-GOVERNMENT

BACKGROUND

2.1 e-Government Services

Citizens are entitled to access and enjoy e-Government

services with ease. Moreover, the citizenry has the

right to have reliable e-Government services to foster

their interactions with varied e-Government

engagements, such as Government to Government

(G2G), Government to business (G2B), and lastly,

government to employee (G2E) services (Choudrie,

et al., 2009). However, it is vital to note the

experiences of the populace due to the failure of e-

Government services that are marred with problems

evidenced by unmet desires. The challenge of these

aspects that cause the e-Government failure is present

among the emerging nations. The course of reviewing

the significance of the e-Government and exploration

of aspects that dictate the creation of e-Government

has received growing support among communities

that tend to analyze e-Government (Scholl, 2014).

This paper focuses on G2S services and the ways

the government employs to provide services to the

populace. Examples of these services include tax

collection, the execution of welfare payments,

conducting the process of renewing licenses and

passports, and facilitating government agencies as

well as taking a lead role in the provision of social and

healthcare services (Fogli and Provenza, 2012).

Concisely, the provision of G2C e-services is a task

assumed by service suppliers, which have been

creating the challenge of overlooking the requisite

needs of the service's users. (Heeks, 2003).

The implications of these unmet needs have

elicited numerous socio-technical challenges coupled

with the absence of programming skills. The role of

e-Government is to reduce the gap in the

requirements between the government and citizens

through an interactive process exemplified with the

provision of effective and superb online services. The

presence of these expectations is key in encouraging

citizens to use the services (Fogli and Provenza, 2012;

Scholl, 2014). The question that is often directed to

the G2C services is: “Which is the essential

requirement needed to foster the understanding

during the formulation and creation of the appropriate

process of e-services?” The resultant outcome is that

service delivery is often negative without the

consideration of the service users. Nevertheless, in

terms of addressing the requisite needs of the G2C e-

services, it is vital to note that limited staff working

for the service providers, such as consultants

recruited for the e-services design demonstrate the

right knowledge for this task.

2.2 e-Government Services in Pakistan

In the context of Pakistan, the e-Government service

was championed in 2002. The inception and

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

62

execution of the e-Government service was

commenced as a department within the Science and

Technology Ministry. The department had been

tasked with the role of monitoring diverse e-

Government projects and ensured that they adhered to

the established practical guidelines (Warriach and

Tahira, 2015). The main role of the e-Government

was centered on the provision of support to

organizations tied to the public sector. The roles were

modeled and expected to enhance productivity,

efficacy, and transparency using ICT and ensure that

the end-users access the services with ease (Ovais

Ahmad et al., 2013). As an integral sector in the

Pakistan context, ICT helped in the development of e-

Government services. The government was

concerned with providing varied activities that were

focused on improving the lives of people. The

feasible strategy adopted by the ICT was key in

reinforcing the achievement of the reformed social

and economic aspects. Therefore, the development of

robust ICT helped to highlight the improvement of

the e-Government services accessed by the citizenry

(Ali et al., 2018).

Pakistan is categorized under emerging nations.

Correspondingly, Pakistan has its share of e-service

problems that involve the acquisition of moderate

ICT infrastructure, the presence of low levels of

literacy, demographic factors, and relative dwarfed

development of e-Government services, and

technological challenges (Ovais Ahmad et al., 2013;

Chandio et al., 2018). Additional challenges notable

in the Pakistan context are issues with the privacy of

data and the dissatisfaction of the services rendered e-

government that is demonstrated between providers

and end-users. Similarly, Almakki (2009)

acknowledges the challenges and difficulties of e-

Government services that are experienced among

emerging nations that are often experienced at the

developmental of the services. Qaiser and Khan

(2010) echo the findings reported by Almakki (2009)

by outlining numerous restrictions that include:

inadequate ICT facilities and poor implementation

process that limits the significance and advancement

of e-Government services (Ali et al., 2018).

2.3 Design Methodologies

User-centered design (UCD) methodologies were

established in 1970 and ultimately became accepted

widely and adopted in 1990 (Sanders and Stappers,

2008). Handler outlooks and concepts are merged

into the software improvement progression regularly

to ensure a better system or service deployment

(Wever, et al., 2008). UCD emerged as being greatly

suitable in designing and developing products for

end-user (van Velsen and van der Geest, 2012; Jacobs

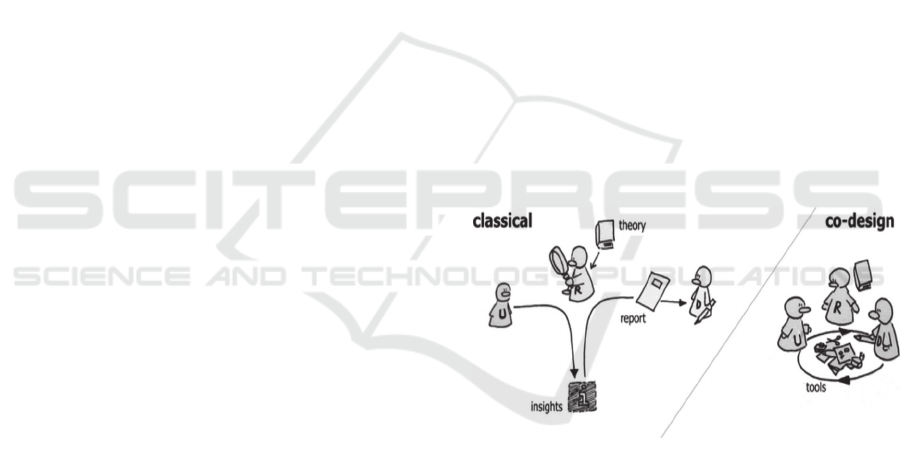

et al., 2019). Figure 1 explains a caricature displaying

the deficiency within the classical user-centered

process of design compared to the co-design

approach, and the rationale for transforming to co-

design approach. Sanders and Stappers (2008, p.11)

stated “the user is a passive object of study, and the

researcher brings knowledge from theories and

develops more knowledge through observation and

interviews”. Moreover, “The designer then passively

receives this knowledge in the form of a report, and

adds an understanding of technology and the creative

thinking needed to generate ideas, concepts, etc.”

(Sanders and Stappers, 2008, p.12). Nevertheless, an

analysis is critical to mentor participants at the

‘performing’ level of creativity, supporting at the

‘adaptive’ level, supporting platforms for resourceful

manifestation at the ‘innovative’ level, and suggest a

delicate account at the ‘designing’ level (Sanders and

Stappers, 2008). Nevertheless, an analysis is critical

to mentor participants at the ‘performing’ level of

creativity, supporting at the ‘adaptive’ level,

supporting platforms for resourceful manifestation at

the ‘innovative’ level, and suggest a delicate account

at the ‘designing’ level (Sanders and Stappers, 2008;

Simonofski et al., 2019).

Figure 1: Classical UCD VS Co-Design (Sanders and

Stappers, 2008).

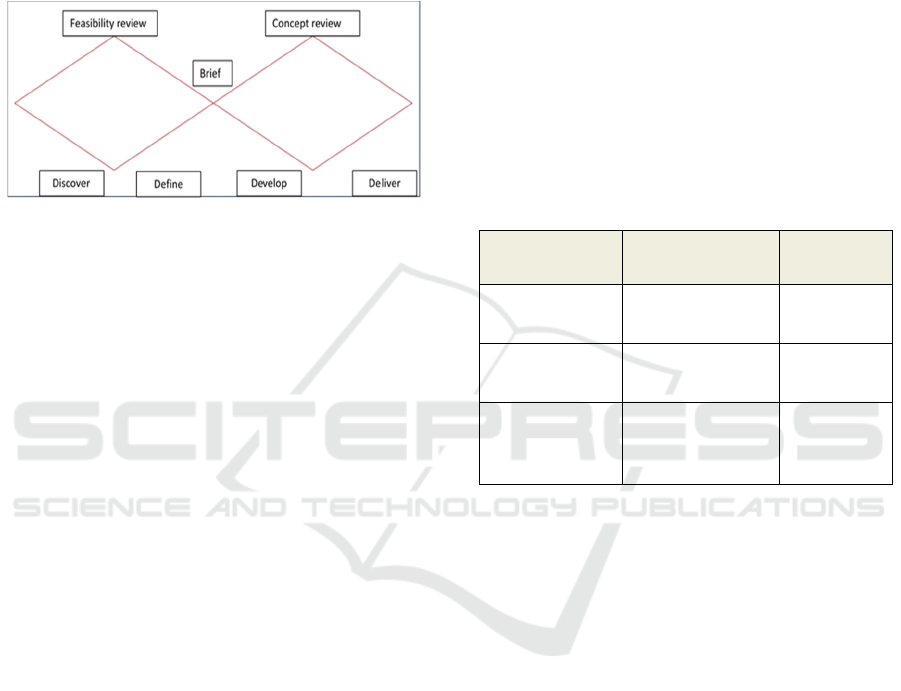

2.4 Double Diamond Model (DDM)

The Double Diamond model (DDM) can be defined

as an basic graphic plan of the process of design as a

creative process (See figure 3) distributed into four

separate stages (Discover, Define, Develop, and

Deliver) representing a typical design process phase

(British Design Council, 2005). These creative

processes reflect various potential ideologies before

refining (i.e. divergent ideas) and narrowing down

ideas to the most suitable ones (i.e. convergent ideas).

DDM designates these four stages to work together as

a map design providing guidelines for the

Government Digital Service Co-design: Concepts to Collaboration Tools

63

organization of thoughts in order to improve the

creative process (JustInMind, 2018). The creative

process is an iterative process (not a linear process),

which implies that the specific ideas are developed,

tested, refined several times to match diverse

thoughts and perspectives of stakeholders; weak ideas

are omitted in the design process (British Design

Council, 2005).

Figure 2: The presentation of the Double Diamond model

(UK Design Council, 2005).

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 Data Collection and Sampling

In-depth interviews were used to collect the views,

ideas, and thoughts from the research subjects, which

helped to categorize G2C e-service design

requirements. Evidence from studies conducted has

reported that the use of a small sample population, such

as between 5 and 50 respondents was sufficient enough

to record a wide range of requirements (Dworkin,

2012). Study participants recruited for this study were

selected purposively. As demonstrated in Table 1, the

purposive sampling approach was employed to recruit

the study participant by reaching out to the potential

respondents. Siau et al. (2010) emphasize on the need

to utilize an appropriate sampling approach to ensure

that different respondents with diverse experiences are

recruited in a study.

This study focused on recruiting stakeholders

identified as users of service, and frontline staff along

with service providers. The author chose to use

interviews since they offer a chance to delve deeper

into the subject being researched, compared to using

surveys (Bell and Nusir, 2017). Cumulatively, the

author carried out 24 in-depth interviews that last

from 45 minutes to one hour. Nonetheless, the author

guaranteed that the experience and familiarity of all

the respondents with the area of investigation (i.e.

G2C e-service design process) was sufficient. All the

interviews began with a brief summary of the

questions in the interview (open-ended), to ensure the

respondents understood the areas being investigated.

Subsequently, the interviewing protocol and

guidelines including additional questions were

explained to participants as an introduction as a way

of facilitating the interviewing process. After a brief

introduction about interview protocol, service users

were supposed to answer questions about their

experiences -What/how do you wish to contribute

and/or enhance your experience with services and

service outcomes? Service providers and frontline-

staff were interviewed on prevailing processes of

design - Which steps are followed by e-Government

projects in Pakistan when creating government to

citizen (G2C) services? This study presents data

analysis and results findings from the comprehensive

interviews in sub-sequent section.

Table 1: The sample population for the in-depth interviews.

Stakeholders Participants

Category

#

participants

Service

Provider

*NITB 6

Service

Frontline-staff

**PITB 6

Service User varied & diverse

Background &

Experience

12

3.2 Data Analysis

The translations of the interview transcripts were

exported to Spreadsheets for data cleaning and

management. This study used the inductive thematic

analysis method to analyze the grouped transcripts

of the research subjects. This process was followed

with the compilation of all the transcripts in a single

file and the analysis of the data executed conducted

using the inductive thematic analysis, which is one

of the popular methods used in qualitative data

analysis. The rationale for selecting this method was

due to its accessibility and flexibility. Additionally,

there are no major limitations that are tied to any

specific theory as the method works with diverse

and changing occurrences. Accordingly, the

description of the study’s dataset was rich with a

throughout interpretation procedure (Braun and

Clarke, 2006).

The procedure for the thematic analysis method

was undertaken in six key phases as elaborated by

Braun and Clarke (2006). The first step involved

familiarization with the data, which involved going

through the data numerous times to achieve a

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

64

comprehensive understanding. The second step

involved the development of the initial analysis from

the transcripts. This step involved the consideration

of the key points that tended to be significant in the

examination of the study interviews (Allan, 2003).

The third phase involved sorting the initial relevant

transcript codes in a bid to identify potential

categories resulting from the interviews. Potential

themes were reviewed in the fourth phase. This phase

involved the process of reviewing and refining

potential categories to ensure that high levels of

consistency are maintained. The fifth step involved

the definition and classification of the categories

derived from the fourth phase using appropriate titles.

The last phase involved the identification of the

satisfied categories and using them to discuss the

study findings in a clear and convincing way.

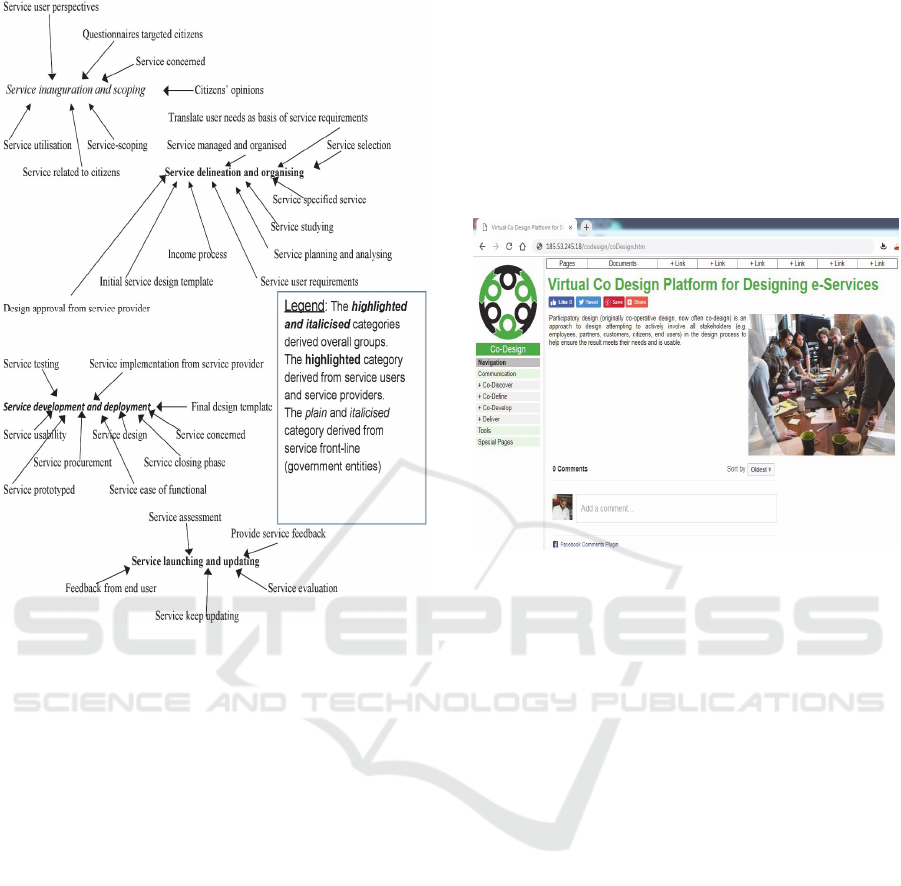

This study derived 30 requirement labels. The four

categories identified involved the service conception,

explanation and organization of service, development,

and deployment of the service, and service unveiling

and implementation. The categorization of the labels

into four groups was undertaken for all the 24

stakeholders involved in the study.

3.3 A Tailored Double Diamond Model

The tailored diamond model (DDM) used in this

study proposed varying weights for the mentioned

stages (Ruhl et al., 2014). Figure 3 is a representation

of the DDM, which is a version redesigned from the

Double Diamond model and the Double Diamond

Model of Product Definition and Design (Hinman,

2012).

The consideration of the varying weights and

stakeholders is documented for the different stages,

which is dependent on the shared interests, tasks, and

requirements among the groups. The stages are

retitled appropriately to ensure that they match with

the expectations of the c-design strategy. As such,

discover was retitled to co-discover. The first two

stages, co-discover and co-define demonstrate a

significant process of definition; whilst the last two

stages consisting of co-develop and deliver indicate

the process of the design.

Figure 3: The Tailored DDM.

The figure above is a representation of the divergent

and though mode that is connected with interview

results. The classification of the G2C’s requirements

and categories are showcased in Figure 4.

The systematic process outlined in Figure 4 spells

out the stakeholder groups that are mapped into

appropriate categories that relate to the DDM phases.

The systematic process further outlines the key

components of defining each stage of design that

matches with the corresponding roles and definitions

purposely to achieve the goal of each design phase

(British Design Council, 2005). It is vital to note that

co-define, co-develop, and co-discover are different

and do not relate to each other due to the fact that they

are found within the stages encompassing the

engaged and the stakeholders.

The Business Process Modelling Notation

(BPMN) denoted in Figure 4 was useful in the

creation of the tailored DDM that ensured that

suitable design tools were utilized in the design

phases. Whereas the BPMN was modeled to operate

internally, it provided a platform for engaging diverse

stakeholders. The three co-design stages are

discussed as follows:

Co-Discover: This is the first stage in the co-

design stage, which is notably identified as the

scoping and service initialization. As such, the design

problem was identified in this stage. Moreover, this

stage was characterized by a wide range of activities,

such as procedures, support activities, and

Figure 4: Co-Design Framework.

Government Digital Service Co-design: Concepts to Collaboration Tools

65

instruments that are used to generate thoughts,

opinions, and views from participants.

Co-Define: This is the second stage where ideas

are filtered from information collected from

participants. The synthesis of ideas at this stage

further involves reviews and eliminations and used to

recommend solutions that are design-led. The

implication of this stage explains the need for

analyzed and synthesized design ideas that are

dependent on the requirements stipulated in the

design brief.

Co-Develop: At this stage, the G2C e-service

participants are first introduced to the solution led by

design (Design Council, 2007, p. 19). The purposes

or resolutions for designing the process of G2C e-

service are expounded in this phase. The development

of the resolutions is key to the demarcating the

requisite objects for the design methodology.

Deliver: This last stage provides the platform for

testing service. This stage which is also known as the

service unveiling and implementation involves the

objects that are a resultant of the previous stage. The

implementation and the delivery process involve the

relationship that required from the inner design staff

only.

4 DATA RESULTS-KEY

CATEGORIES

The main categories identified were based on

frequency as the criterion indicator. Notably, Goffin

et al. (2006) acknowledge that frequency as one of the

vital indicators. The rationale for selecting this

criterion emanated from the reviewed literature that

stipulated how frequency was important such that a

minimum of 25% formed the baseline for the

participants. The overwhelming mention of the

frequency is an indicative factor that this category

was candid as demonstrated in Figure 5.

Nevertheless, it was difficult to determine the

category that was significant given that the results

were not 100%. As such, identified categories are as

follows:

4.1 Service Deployment

The formulation, creation, and deploying services

forms one of the vital categories alongside the

stakeholder groups. Given that the resulting

frequency was 27%, this category is significant when

compared to the group of service providers.

Moreover, this category offers significant attributes to

the users of the service and the group consisting of

front-line service staff. The significance of this

category is characterized by diverse classifications of

the individual stakeholders who are tasked with the

responsibility of making decisions of the

requirements within this category.

4.2 Service Launching and Updating

This category which is 15% comes last in terms of

frequency when compared with other groupings. The

explanation for this significant difference is that the

prospects of launching and updating the service

happen continuously as the services work on

organizing the services with the intention of meeting

the diverse needs of the end-users. The requirements

are elicited from the expectations from stakeholders

using the service and the responses from the service

frontline staff. As an integral component in the

service development, this category demonstrates that

it is only significant to the group of service providers

and not the other groupings.

4.3 Service Delineation and

Organization

This category comprises of the responses, which

estimated at 25% of the frequency when compared

with the other groupings. The responses are derived

from the stakeholder groups, which demonstrates a

high significance towards other groups. However,

this category ranked a low significance in the services

providers groups. Similarly, the categories consisting

of the users of service, as well as the frontline staffs,

are ranked highly as exhibited by the frequency

scores. As such, decision-makers need to take into

consideration vibrant requirements by restructuring

the current service design model.

4.4 Service Inauguration and Scoping

This category which accumulated 21% of the

frequency of mention fails to showcase the integral

significance, which other categories can depend on.

Evidently, this category is built on the assertions and

viewpoints collected from the service frontline staff.

This reveals how government staff exhibit the highest

correspondence in the event a service has design

glitches that result from the daily usage of the service

by the end-users of the service. Conversely, this

category signifies a modest standing when compared

with the other groupings based on mention frequency.

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

66

Figure 5: Cognitive Mapping.

5 CO-DESIGN FRAMEWORK -

FIELDWORK TESTING

A qualitative research method was conducted and led

by author (i.e. predetermined interview questions

using the focus group discussions (FGDs) as form of

semi-structured interviews) with total of 24

participants recruited to participate in this study. The

involvement of the participants was hinged upon to

generate intriguing, appropriate, and subjective

information, such as their experiences with the design

G2C e-service. In the Pakistan context, prototype

evaluation and post-test interview questions and tasks

were administered to the participants to validate the

proposed framework. Co-design Wiki is an

innovative workspace-platform (see figure 6). The

innovation workspace was produced by realizing

several features (core functions) as these functions

explain four phases of the typical design process. For

example, generating checklists for possible services,

creating an account, upload media that informs

design, search, a toolbox including options and text

boxes for providing feedback on the service design

process. Furthermore, rating and voting features grant

participants the opportunity to assess the service

design characteristics. The FGDs with the

participants lasted between 45 minutes and 60

minutes. Study participants were encouraged to

collaborate in task-based planning. As such, they

were required to provide answers to the semi-

structured questions, which were formulated to assess

their adequacy.

Figure 6: Online collaborative Co-design Wiki.

The three main themes resulting from this study,

namely, Creativity and collaborative platform,

Situating and tailoring co-design tools; and

limitations and shortcomings of involvement.

Moreover, the six subthemes resulting from the study

can be identified as follows: demonstrating

engagement, communication, originality, design

instruments of a collaborative nature, interaction and

some advantages and disadvantages. The collective

themes demonstrated varying comparisons in terms

of the groups of the service provider and users of the

service among the other groups. However, the groups

showcased diverse viewpoints that included the

opportunities and difficulties of using a proposed

prototype that comprised the end-users in the process

design. The findings were identified using inductive

thematic analysis as an example of theoretical

analysis for the FGD’s answers. The three major

themes and sub-themes from the study were identified

and explained as follows:

5.1 Creativity and Collaborative

Platform

This platform was presented with positive reports

drawn from the experiences of the participants who

had interacted with the proposed prototype. Some of

the participants even identified the proposed

Government Digital Service Co-design: Concepts to Collaboration Tools

67

prototype as intriguing. It is vital to note that the

frontline staff took part in the entire assessment

process. However, there are numerous participants

who revealed the significance of collaboration with

the exception of one participant who reported the

need to improve the prototype’s interface. The

significance of this theme is exhibited as it emerged

from the merger of two themes, namely, user

communication and involvement, and cooperation

co-design platform.

5.2 Situating and Tailoring Co-design

Tools

Participants from the groups dominated by the

frontline staff took part in the assessment aimed

toward the improvement of the diverse stages of the

iterative design process. Accordingly, the

involvement of this group was geared towards

making most of the opportunity to present ideas on

the process of designing e-services. The previous

suggestion sought by the frontline staff groups

received a warm reception among the groups of the

service provider. Nevertheless, the main objective of

the groups was to position the co-design tools in all

the design phases purposely to enable diverse

stakeholders to modify their varying viewpoints.

5.3 Limitations and Shortcomings of

Involvement

The adoption of design instruments differed

throughout the design phases. For instance, the

frontline staff groups demonstrated higher levels of

interest when compared with other groups of the

service provider. However, there were notable

limitations that were evidenced by the service

provider in regard to the participation of users of

services. The challenges were evidenced through the

design process of the services due to the lack of

knowledge and experience. Evidence from groups

like the frontline staff showcased wide-ranging

opportunities through which they could reduce the

fears of supporting the participants in a more effective

and timely manner. Moreover, the frontline staff

groups did not originate from the service providers.

6 CONCLUSION

This study has provided a significant co-design

activities emerge from a diverse set of service design

stakeholders (see figure 4). Identified themes and

related sub-themes (see figure 5).

Underpin our blueprinting process construction

and subsequent technique selection. Author describes

a design study where co-design is utilized in a

participant (stakeholder group) specific e-

Government service co-design process. Working with

several e-Government stakeholders in Jordan.

Elements of participant and stakeholder group

cognitive models were then synthesized into a

context-specific co-design blueprint, itself based on

the UK Design Council’s DDM. The ‘co-develop’

and ‘co-define’ stages demand convergent thinking to

stimulate diverse stakeholder groups to identify the

concrete strategies for managing and planning

alternative practices by synthesizing the problem. In

contrast, the co-discover stage needs more divergent

thinking, covering different stakeholders for more

robust exploration in the problem phase. The

blueprint was then operationalized (as a practical

process model) to elaborate on the specific service

design steps.

Moreover, it is supporting the designate tools

needed for effective service co-design usage. The

operationalized design process offers an executive

approach that can be utilized to develop e-services in

a governmental domain-context. Remarkably, the

discursive nature of our collaborative process and the

rating tools employed were particularly popular

amongst stakeholders.

This study had a number of limitations primarily

linked to a focus on a single context. Participant

numbers are small and issues are likely to have a

context specific nature. Consequently, the findings

may not be generalizable, but design oriented

qualitative research provides depth, effectiveness and

transferability rather than generalizability. Future

research could determine the extent to which different

stakeholder groups are influenced by the size of task

ahead. It may also be the case that this is linked to the

historical experience of each stakeholder.

Based on the findings from this study, the

recommended approach is the co-design framework

for the G2C e-service for its effectiveness in mapping

out the tailored requirements. Additionally, co-design

deems appropriate as it is integral in the selection

process mechanism as well as matching e-Service

design categories with relevant design methodologies

throughout the phases of the process design.

Therefore, the implementation of this approach will

foster communication among key stakeholders

involved in the design process for the G2C e-service.

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

68

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author would like to acknowledge of the

appreciation of the Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz

University

REFERENCES

Alam, I.: An exploratory investigation of user involvement

in new service development. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science 30(3), 250 (2002).

Ali, M.A., Hoque, M.R. and Alam, K.: “An empirical in-

vestigation of the relationship between e-government

development and the digital economy: the case of Asian

countries”, Journal of Knowledge Management Vol. 22

No. 5, pp. 1176-1200. (2018).

Allan, G.: A critique of using grounded theory as a research

method. Electronic Journal of Business Research Meth-

ods 2, 1-10 (2003).

Almakki, R.: Communities of Practice and Knowledge

Sharing in E-government Initiatives, The University of

Manchester, Manchester (2009).

Anthopoulos, L. G., Siozos, P., & Tsoukalas, I. A.: Apply-

ing participatory design and collaboration in digital

public services for discovering and re-designing e-Gov-

ernment services. Government Information Quarterly

24(2), 353-376 (2007).

Axelsson, K., & Melin, U.: Talking to, not about, citizens–

Experiences of focus groups in public e-service devel-

opment. In International Conference on Electronic

Government 2007 (pp. 179-190). Springer, Berlin, Hei-

delberg (2007).

Braun, V., & Clarke, V.: Using thematic analysis in psy-

chology. Qualitative research in psychology 3(2), 77-

101 (2006).

Bridge, C.: Citizen Centric Service in the Australian De-

partment of Human Services: The Department's Expe-

rience in Engaging the Community in Co‐design of

Government Service Delivery and Developments in E‐

Government Services (澳大利

亚人类服务部以公民

为中心的服务

:

该部门在促进群体参与协同设计政

府服务提供和发展在电子政府的经验

). Australian

Journal of Public Administration 71(2), 167-177

(2012).

British Design Council, 2005. The double diamond design

process model, [Online]. Available at :<http://www.

designcouncil.org.uk/designprocess/>, last accessed

2020/01/19.

Chandio, A. R., Haider, Z., Ahmed, S., Ali, M., & Ameen,

I. (2018). E–Government In Pakistan: Framework of

Opportunities and challenges. GSJ, 6(12).

Choudrie, J., Wisal, J., & Ghinea, G.: Evaluating the usa-

bility of developing countries’e-government sites: a

user perspective. Electronic Government, an Interna-

tional Journal 6(3), 265–281 (2009).

Cordella, A., & Tempini, N. E-government and organiza-

tional change: Reappraising the role of ICT and bureau-

cracy in public service delivery. Government Infor-

mation Quarterly, 32(3), 279–286 (2015).

Bell, D., & Nusir, M. (2017, January). Co-design for gov-

ernment service stakeholders. In Proceedings of the

50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sci-

ences.

Design Council. 2007. The design process: Eleven lessons:

managing design in eleven global companies, [Online].

Available at :<http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.

uk/20080821115409/ designcouncil.org.uk/en/about-

design/managingdesign/the-study-of-the-design-pro-

cess>, last accessed 2020/01/30.

Dworkin, S. L.: Sample size policy for qualitative studies

using in-depth interviews. Electronic Government (pp.

1–9). Springer (2012).

Fogli, D., & Provenza, L. P.: A meta-design approach to the

development of e-government services. Journal of Vis-

ual Languages & Computing 23(2), 47-62 (2012).

Jacobs, C., Rivett, U., & Chemisto, M. (2019). Developing

capacity through co-design: the case of two municipal-

ities in rural South Africa. Information Technology for

Development, 25(2), 204-226, DOI:

10.1080/02681102.2018.1470488.

JustInMind. 2018. The Double Diamond model: what is it

and should you use it?, [Online]. Available at :<

https://www.justinmind.com/blog/double-diamond-

model-what-is-should-you-use/>,last-accessed

2020/03/21.

Goffin, K., Lemke, F. & Szwejczewski, M.: An exploratory

study of ‘close’supplier–manufacturer relationships.

Journal of operations management 24, 189- 209.

(2006).

Heeks, R.: Most egovernment-for-development projects

fail: how can risks be reduced? (Vol. 14). Institute for

Development Policy and Management, University of

Manchester Manchester (2003).

Hinman, R.: The mobile frontier. “O’Reilly Media, Inc”

(2012).

Kim, Suk Kyoung, Min Jae Park, and Jae Jeung Rho. "Does

public service delivery through new channels promote

citizen trust in government? The case of smart devices."

Information Technology for Development 25, no. 3

604-624 (2019).

Ovais Ahmad, M., Markkula, J., & Oivo, M.: Factors af-

fecting e-government adoption in Pakistan: a citizen's

perspective. Transforming Government: People, Pro-

cess and Policy 7(2), 225-239 (2013).

Qaiser, N. and Khan, H.G.A.: “E-government challenges in

public sector”, International Journal of Computer Sci-

ence, Vol. 7 No. 5, pp. 310-317 (2010).

Ruhl, E., Richter, C., Lembke, J., & Allert, H.: Beyond

methods: Co-creation from a practice-oriented perspec-

tive. In Proceedings of Design Research Society Bien-

nial International Conference, Umeå, Sweden (Vol. 1,

No. 1, pp. 967-979 (2014).

Sanders, E. B.-N., & Stappers, P. J.: Co-creation and the

new landscapes of design. Co-Design 4(1), 5–18

(2008).

Government Digital Service Co-design: Concepts to Collaboration Tools

69

Simonofski, A., Snoeck, M., & Vanderose, B. (2019). Co-

creating e-Government Services: An Empirical Analy-

sis of Participation Methods in Belgium. In Setting

Foundations for the Creation of Public Value in Smart

Cities (pp. 225-245). Springer, Cham.

Scholl, H. J.: The EGOV research community: An update

on where we stand. In Electronic Government (pp. 1–

16). Springer (2014).

Siau, K., Tan, X., & Sheng, H.: Important characteristics of

software development team members: an empirical in-

vestigation using Repertory Grid. Information Systems

Journal 20(6), 563-580 (2010).

Stegaru, G., Danila, C., Sacala, I. S., Moisescu, M., &

Stanescu, A. M.: E-Services quality assessment frame-

work for collaborative networks. Enterprise Infor-

mation Systems 9(5-6), 583-606 (2015).

Twizeyimana, J. D., & Andersson, A.: The public value of

E-Government–A literature review. Government infor-

mation quarterly (2019).

van Velsen, L., van der Geest, T., ter Hedde, M., & Derks,

W.: Requirements engineering for e-Government ser-

vices: A citizen-centric approach and case study. Gov-

ernment Information Quarterly 26(3), 477-486 (2009).

Warriach, N.F. and Tahira, M.: “Impact of information and

communication technologies on research and develop-

ment: a case of university of the Punjab-Pakistan”, Pa-

kistan Journal of Library and Information Management,

Vol. 15 (2015).

Wu, A.: Convertino, G., Ganoe, C., Carroll, J. M., & Zhang,

X. L. Supporting collaborative sense-making in emer-

gency management through geo-visualization. Interna-

tional Journal of Human-Computer Studies 71(1), 4-23

(2013).

Wever, R., Van Kuijk, J., & Boks, C. User-centred design

for sustainable behaviour. International Journal of Sus-

tainable Engineering, 1(1), 9–20 (2008).

Zhao, Y., Tang, L. C., Darlington, M. J., Austin, S. A., &

Culley, S. J.: High value information in engineering or-

ganizations. International Journal of Information Man-

agement 28(4), 246-25 (2008).

Zheng, P., Wang, Z., Chen, C. H., & Khoo, L. P. (2019). A

survey of smart product-service systems: Key aspects,

challenges and future perspectives. Advanced Engi-

neering Informatics, 42, 100973.

ICE-B 2020 - 17th International Conference on e-Business

70