Understanding How People Weigh the Costs and Benefits of using

Facebook

Jack McClary

1

and Sid Stamm

2

1

Independent Researcher, Seattle, WA, U.S.A.

2

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, Terre Haute, IN, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Privacy, Cost-benefit Analysis, Social Network.

Abstract:

Much work in privacy focuses on educating a system’s users so they will be better armed to take action based

on the benefits and drawbacks of how their data is treated. Intuitively, this makes sense; one may expect people

who perceive more benefit than risk in a system will elect to use it, but our research shows that is commonly not

the case. We surveyed users of a social network to quantify what they perceive as the benefits and drawbacks

of the platform. Given their net “value” perceived, we would have expected those who see mostly drawbacks

(or a net cost) in its use to abandon the platform for a more privacy-preserving alternative. What we found was

that only 62% of individuals we surveyed acted so rationally—the remainder either chose to use a platform

they felt had a negative impact on their life, or chose to abandon one that served them favorably. This result

indicates there are strong factors beyond rational cost/benefit analysis that lead people to decide what social

platforms they use. This means that privacy professionals must focus not only on building transparency and

choice, but also constructing viable alternatives so people do not feel pressured into using a platform they see

as a net loss of personal privacy.

1 INTRODUCTION

When you interact with a service or entity, you re-

veal some information about yourself. In the physi-

cal world, most people are aware of what information

they are giving to those around them and how it can

be used (Mayer-Schonberger, 2009). Online, how-

ever, this is not always the case: many online services

will sell or use the information they gather about their

customers for non-obvious purposes. While these ser-

vices typically provide access to privacy policies that

outline this behavior, McDonald et al. showed that

even after participants read the privacy policy, gener-

ally they still do not fully understand how their infor-

mation can be used (McDonald et al., 2009). This fail-

ure to understand privacy policies implies that there

is a disparity between what information is correct and

what the reader believes is correct (Staszak, 2016).

This gap in understanding, which we refer to as the

“privacy perception gap”, may even manifest as ani-

mosity and distrust towards the service. While a sig-

nificant amount of research has been done on how to

close this gap (Kay and Terry, 2010; Kunze, 2008;

Lavesson et al., 2008), we seek to identify how read-

ers use their understanding to interact with online sys-

tems. For example, Kelley et al. created a graph-

ical representation of privacy policies to help read-

ers understand the information intended to help them.

They were successful in creating a chart that allows

users to quickly interpret privacy policies more ac-

curately, however, they did not measure the differ-

ence in a user’s willingness to continue using the soft-

ware (Kelley et al., 2009). What we want to under-

stand is, once people know what an online service

does with their data, will they act according to their

judgment about how respectfully the service treats

their data.

2 RELATED WORK

Privacy is increasingly important to users of Face-

book, according to Dey et. al (Dey et al., 2012). In

2018, Vishwnath et al. showed how people attempt to

balance “social fulfillment” with their privacy settings

on Facebook (Vishwanath et al., 2018), and Govani et.

al show that students who are aware of risks still over-

value social interactions (Govani and Pashley, 2007).

Balancing privacy and social fulfillment can only be

526

McClary, J. and Stamm, S.

Understanding How People Weigh the Costs and Benefits of using Facebook.

DOI: 10.5220/0010258405260533

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2021), pages 526-533

ISBN: 978-989-758-491-6

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

rationally done if people are fully aware of how their

data is used and and can control it. Many have worked

on the problem of closing the privacy perception gap

by educating users, and the strategies for this vary.

One strategy is to make privacy policies easier to

understand. Kelley et al. propose standardized quick

summary charts (“nutrition labels”) for privacy poli-

cies to enable users quick access to the personal in-

formation being used (Kelley et al., 2009). There

were many iterations of these labels culminating in

a grid of colorful symbols representing what infor-

mation would always be taken, what information the

user could opt-out of being taken, what information

the user could opt-into being taken, and what infor-

mation would not be taken. The researchers found

subjects were receptive to this display and also that

subjects could more quickly and accurately answer

questions about privacy policies represented in this

fashion. While this is a successful way to educate

users, the authors did not measure how this affected

a participant’s desire to use the software behind the

privacy policy.

Another gap-closing strategy is to standardize the

format and language of End User License Agreements

(EULAs) themselves. Kunze et al. assert that a

standard format would balance power between users

and developers and provide a fair mechanism for dis-

putes (Kunze, 2008). This work argued that improv-

ing EULAs could improve “virtual world” software,

arguing standardization provides both legal and eco-

nomic improvements. By forcing EULAs to be in

plain language, the authors assert companies will ben-

efit from informed consent agreement stronger than

what is often standard practice (signing the EULA

without reading it). When these standard EULAs giv-

ing all the power to the developers are challenged

in court, the agreements often failed to hold (Kunze,

2008). By giving more power to the user, these agree-

ments become more reliable, and not just easier to un-

derstand. By examining both sides of EULAs, Kunze

et al. assert this standardization would help both com-

panies and users by balancing power and making the

agreements more binding (Kunze, 2008).

A similar practice of making a unified format

could be used with privacy policies; many have tried

similar approaches, such as icons (Holtz et al., 2011;

?) or short privacy notices (Utz et al., 2019) (cookie

notices often used to comply with GDPR). Hoping

to automatically standardize privacy policies, Hark-

ous et al. developed Polisis (a machine learning-

based privacy policy analyzer) to interpret and present

privacy policies at a higher level more accessible to

users (Harkous et al., 2018).

Other work turns privacy notices and policies into

something users can interact with to learn more about

the site’s privacy practices. The Pribots project (Hark-

ous et al., 2016) attempts to close the privacy per-

ception gap with a virtual entity with which users

may converse to learn about their privacy choices and

settings. Other work suggests boosting the usabil-

ity of privacy settings themselves will aid educated

users (Lipford et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011).

In “Noticing notice,” Good et al. used a partic-

ipant’s acceptance of software as an indication that

education was successful (Good et al., 2007). Their

work is similar to this paper’s contributions, but does

not capture the case where the users identify a prod-

uct as beneficial yet still avoid using it. In “Noticing

notice,” participants were asked to read EULAs and

were shown a summary of the EULA before or af-

ter the consent page (depending on which group they

were assigned). When compared with the group that

was not given any summary, Good et al. noted that

those who were pre-briefed with a summary spent

more time installing the software and often declined

agreements. The authors asserted that effective edu-

cation leads to a change in behavior, but it is not ob-

vious that “knowing” leads to “doing”.

In this paper, we further examine the “Noticing

notice” underlying assumption (Good et al., 2007)

that education about a site’s data practices will change

users’ behaviour.

3 DO PEOPLE ACT ON THEIR

EDUCATION?

We hypothesize that educating people on risks associ-

ated with a social networking site has a smaller effect

than expected from rational actors. To limit the scope

of this paper we focused on one social network: Face-

book. To break down our hypothesis into questions

we can test, we split it into three parts.

Question 1. Do people realize that there is an in-

herent risk to using social media?

We expect they do since many security breaches

and controversial policies have been in the news re-

cently, and thus educated people more about risks of

using the Internet. This combined with a broad defini-

tion of risk (a possible negative impact on one’s life)

suggests that most people will be aware of the risks.

Identifying whether people see this inherent risk will

motivate the other two questions because people must

make non-trivial decisions based on their education.

Understanding How People Weigh the Costs and Benefits of using Facebook

527

Question 2. Do people practice reasonable cost

benefit analysis?

We expect they do not because many people con-

sider social media to be a waste of time. This com-

mon perception reduces perceived value in social me-

dia, so even if the risk and impact of loss is low, the

cost of participation will still outweigh any potential

value. Question 2 is core to this paper: if people do

not behave in alignment with their values, changing

their values (via education) will not likely change be-

haviour.

Question 3. Does perceived value from Facebook

directly correlate to frequency of use?

If people employ cost benefit analysis, we expect

those who see less (or negative) value from Facebook

to have less motivation to use it, or they may perceive

more value in aspects of Facebook that do not re-

quire consistent use. Furthermore, we anticipate peo-

ple who fail to practice cost-benefit analysis will see a

very small negative value in Facebook, which may in-

dicate the effort of deactivating their account doesn’t

seem worth the time required.

3.1 Contributions

Much work is being done to see if users can be effec-

tively educated, and some even interpret their reaction

as purely a result of their education, but it is not clear

if people are truly using their education to make deci-

sions. Our work suggests they don’t.

In this paper, we use the results of a survey to

show that (1) people realize there is potential risk or

costs in using Facebook, (2) even knowing there is a

cost, peoples’ usage patterns do not commonly align

with their perception of cost or benefit in use of the

social network, and (3) there is a correlation between

a person’s perceived value of Facebook and their in-

tensity of use. We also dig deeper into our results to

draw some additional insights about what externali-

ties may influence peoples’ perception of costs and

benefits of using Facebook.

4 METHODOLOGY

While we seek general knowledge about all social net-

working platforms, our survey focused on the most

widely used network on our campus: Facebook. To

answer the three questions listed in Section 3, we ad-

ministered a survey to volunteers from the student

population of our university to measure their percep-

tion of risks and values, and their usage patterns of

Facebook.

Our work was conducted with an exemption

granted by our university’s ethics board (Institutional

Review Board) as protocol #RHS0329. To protect

the subjects, all identifying information was sepa-

rated from survey responses and after data collection

was completed, the identifying information was de-

stroyed.

Our survey was split into two parts: (1) we first

gathered information on how intensely individuals

used the social network if at all, and then (2) iden-

tified what attributes people deem to be benefits (val-

ues) and costs (risks) of using the social network.

4.1 Identifying Value and Risk

Perceptions

Perceived value ratings are relevant to all three ques-

tions we seek to answer. We asked survey respon-

dents what they perceive as both positive and nega-

tive aspects of using Facebook. From their answers,

we can identify where the population generally per-

ceives risk, where they see benefit, and the intensity

of these feelings.

We hypothesized that the net perceived value (sum

of benefits minus sum of costs) directly correlates

with intensity of use on the social network. Specif-

ically, respondents who see more value than risk to

their activities on the site will choose to use it and

those who see more risk than value will choose not

to use it. This leads us to classify “rational” actors as

those whose usage follows their perceived value.

On one hand, those who see Facebook as a net

positive are rational actors if their perceived bene-

fit (value) outweighs the perceived cost (risk), and

it would follows that such a respondent would use

the platform. On the other hand, those who perceive

Facebook to be a net negative (more risk than value)

are rational actors if they choose to avoid or lessen

their use of the platform.

4.2 Identifying Usage Patterns

Usage pattern questions are needed to gather data on

how often or with what intensity a respondent uses

Facebook. These patterns are identified by the user’s

frequency of use, account history with Facebook, and

whether they have decided to deactivate their account

(and how long ago). This part of the survey is not

only necessary to find a correlation between usage in-

tensity and value seen, but also informed us about re-

spondents’ decisions on whether to use Facebook or

not.

Combining this usage information with that of the

value and risk parts of the survey, we can estimate

ICISSP 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

528

whether or not the respondents are rationally applying

cost-benefit analysis on their use of Facebook.

4.3 Survey Design

At first we sought mainly to answer Question 2, so the

surveys were designed with information needed to de-

termine if people weigh the costs and benefits of using

Facebook. Question 3 is an extension of Question 2,

seeking whether people use Facebook with intensity

matching their perception of its net value. Related,

we anticipated existence of a specific value percep-

tion below which users deactivate their accounts. To

find this “minimum-bar”, we first needed to quantify

what peoples perceive as benefits and costs of using

Facebook.

We initially planned to present a series of posi-

tive and negative “aspects”, where respondents were

asked to rate how valuable they perceived the posi-

tive aspects, and how costly they perceived the neg-

ative ones. We noticed that classification into posi-

tive and negative categories would introduce bias so

we revised our survey to allow respondents to rate all

aspects on a scale including both costs and benefits.

The survey questions used a scale of -5 to 5, where

-5 was the highest cost and 5 was the highest bene-

fit. This way the authors’ judgment about “good” and

“bad” aspects should not influence the responses. To

create each aspect, we looked at different features of

Facebook and attempted to generalize their function,

for example the feature of showing a specific day in

a past year was isolated into “A way to connect with

your past”.

Iterative Bias Removal. Before administering the

survey, we attempted to remove bias (attempting to

make each aspect appear as it could be a cost or a

benefit) by making the language we used as neutral as

possible. Then we repeatedly asked a small set of peo-

ple how biased our set of “aspect” phrases sounded

and then revised the phrases. Our goal was to obtain

phrases as neutral or factual as possible, changing bi-

ased phrases like “a way for trackers to spy on me” to

more outcome-driven phrases like “a way for content

providers to target my interests”.

4.4 Collection

We offered the resulting email survey to the student

population of our university, offering five $10 gift

cards to randomly selected respondents to encour-

age responses. To handle the random reward, we

needed to collect personally identifying information

about our respondents in addition to their survey re-

sponses. In the interest of smooth IRB approval, we

split survey responses into two isolated data sets: one

that contained the research questions and one that

contained the respondent’s contact information. To

avoid “ballot box stuffing”, our survey verified a re-

spondent’s contact information was not yet in our data

set before splitting and recording the entire response.

This entire process was vetted and approved by our

university’s IRB, the survey data was collected by a

third party, and then only provided to us after be-

ing scrubbed of potentially personal information. We

protected privacy of our respondents by separating

their PII from their research question responses, and

only having access to contact information of the five

randomly-selected gift card winners. Once the gift

cards were distributed, the contact information data

set was destroyed.

We initially attempted to gather responses in per-

son, at our university’s dining hall. Given the large

majority of students walk through there every day, we

expected a good response rate. It turned out that very

few were willing to stop and take a short survey on

their way through the dining hall, so we elected to

request responses to the survey by sending a single

message to all 2200 university students. Within two

weeks we had collected 555 responses to the survey

with 450 unique and complete responses.

5 RESULTS

Before analyzing the results we removed any re-

sponses that did not fully complete the entire survey.

To our surprise, each question received a full range of

responses (-5 to 5) and so we were not able to remove

“outliers” based on any sort of response pattern.

The majority of respondents’ behavior regarding

Facebook does in fact reflect their net values. This im-

plies that further education of Facebook users about

how the platform uses their data would result in over-

all behavior change. However, the number of students

failing to practice risk analysis suggests that educa-

tion is not as effective as many believe.

Question 1 (Results). People realize there is risk in

the use of the social network platform. 98.6% of re-

spondents acknowledge risk existed in the platform.

This was identified by finding all respondents who

identified at least one negative response in the values

section of the survey; as prompted, this was a respon-

dent’s indication of a “cost” to using Facebook.

Understanding How People Weigh the Costs and Benefits of using Facebook

529

Question 2 (Results). People do not always prac-

tice reasonable cost benefit analysis. 62%, less than

two-thirds of respondents were identified as practic-

ing and acting on valid cost benefit analysis. This

was measured by comparing the sum of the values

assigned to aspects for each individual’s response to

whether or not the individual has an active account.

If the respondent perceived an overall negative value

(cost) and yet still uses the platform, we marked this

as not practicing cost benefit analysis. Value sums of

zero indicate neutrality, and we considered all such re-

spondents to be practicing cost-benefit analysis. (The

net-zero values are included in the 62% figure and

were less than two percent of responses.) The break-

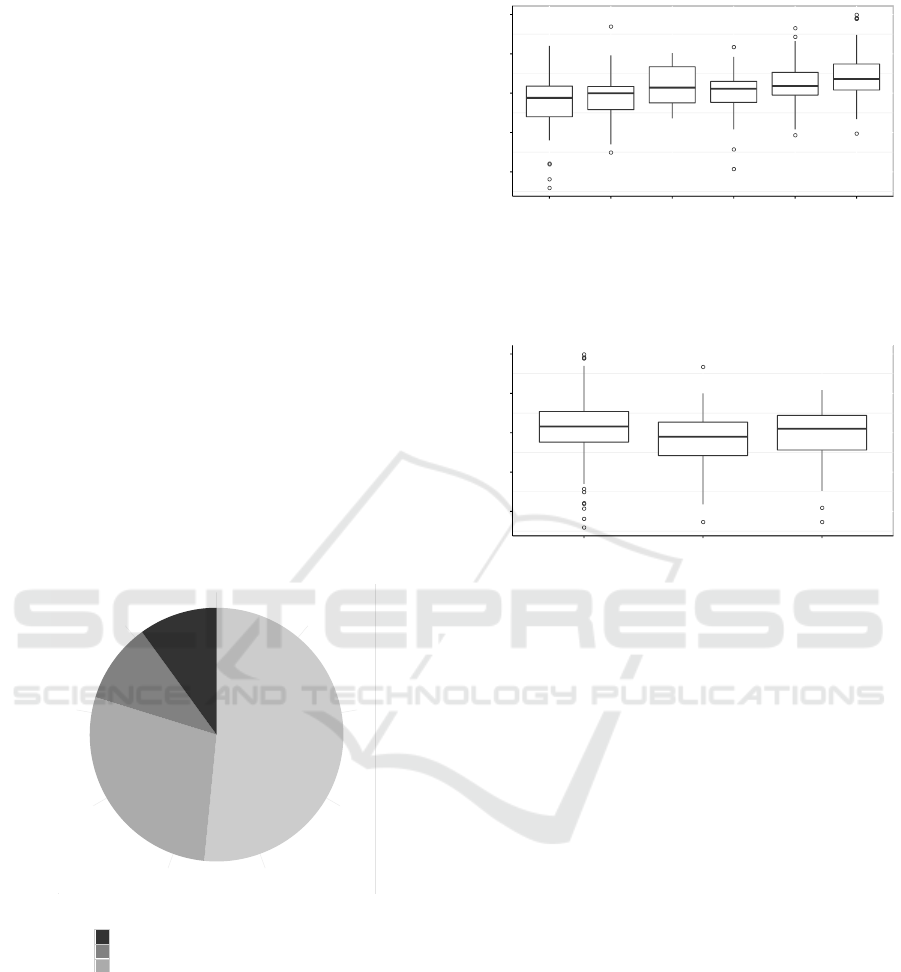

down of the four possible groups is seen in Figure 1.

Question 3 (Results). There does seem to be a

slight correlation between perceived net value and in-

tensity of use. The positive correlation can be seen in

the trend displayed by the mean value results in Fig-

ure 2: the more positive value respondents perceive

in the platform, the more frequently they use it. It is

important to note that the range of perceived values is

not very wide; this suggests that as a whole, users of

the platform are fairly neutral.

Categories of Users

Don't Have Facebook See Negative ( 10% )

Don't Have Facebook See Positive ( 10.22% )

Have Facebook See Negative ( 28.22% )

Have Facebook See Positive ( 51.56% )

Figure 1: The breakdown of the net value respondents as-

sign to Facebook and whether they use it. 62% of respon-

dents either see a net negative value and have no account or

see net positive value and have an account. The remaining

38% seem to behave contrary to their value judgment of the

social network.

6 FURTHER INTERPRETATION

By administering a survey through an all-student

email, we were able to collect survey responses from

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

−100

−50

0

50

100

Less than

once a

month

Once a

month

A few

times a

month

About once

a week

A few

times a

week

Every Day

Frequency

Value

Figure 2: A comparison of use frequency and value seen.

Respondents who see more value also seem to use Facebook

more often.

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

−100

−50

0

50

100

Have a Facebook

account

Deactivated Facebook

account

Never had a Facebook

account

Account Status

Value Seen

Figure 3: Comparison between net value perceived and ac-

count status. Those with no account tend to perceive less

net value in the use of Facebook, but not by a substantial

amount.

a large, strongly representative sample of the stu-

dent body. We compared the demographics of the

responses to those of the entire population of stu-

dents to identify how representative our sample was.

The largest difference we saw was that of male stu-

dents; the male student population of our university

was 75.3%, but was 64.9% of the sample responses.

All race demographic sizes we measured fell within

10% of those of the student population, with many

within 5% of expected. This all indicates the sample

is a strong representation of our University’s student

population.

6.1 Demographic Cross-sections

Across all race and sex sub-groups, percentages of

those who saw and didn’t see benefit in Facebook, and

those with or without an account, varied widely. For

every subgroup, the portion of respondents who prac-

ticed valid cost benefit analysis fell within ±4% of

the result of the whole sample. This did not hold for

subgroups based on academic major.

ICISSP 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

530

A way to spread your ideas

A way to stay connected as you meet people

A way to summarize your character

An archival method

A way to learn about current events

A way to learn about local events

A way to message people

A way to seek help

A way to expose people

A way to find new people

A way to have fun

A way to keep track of events

A use of my time

A way for advertisers to learn about me

A way to build community

A way to connect with your past

A source of knowledge about family

A source of knowledge about friends

A source of objective knowledge

A source of self image

A place for personal data

A place to discuss differing opinions

A place to play games

A source for news

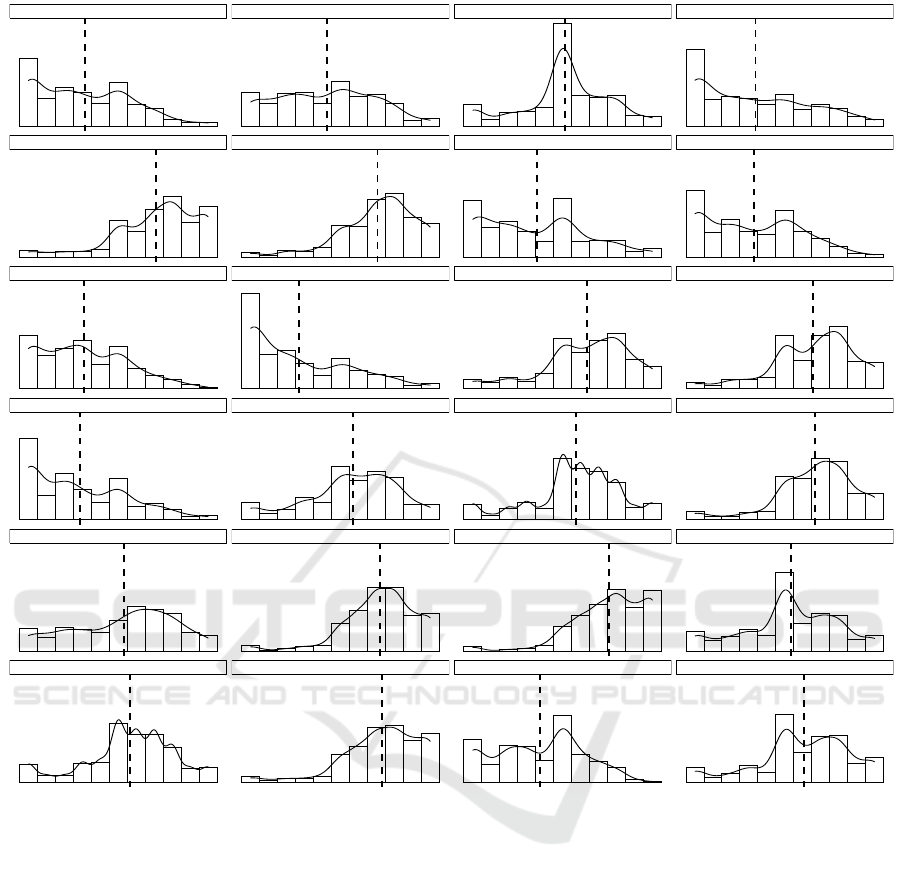

Figure 4: Survey respondents were asked to rate each of these aspects of Facebook on a scale of -5 (most costly, left side of

each histogram) to 5 (most beneficial, right side of each histogram). Here histograms can be seen for each aspect including a

mean response as a vertical dotted line. Participants were presented these “value” questions in random order.

Insight 1. There was no clear correlation between

perceived net value of Facebook and the student’s aca-

demic major. It’s important to note that our sample

was all math, science and engineering majors, so this

may not be very significant.

Insight 2. On average, female respondents reported

a higher perceived net value (11.4) than male respon-

dents (1.3) in a possible range of -120 to +120.

6.2 Insights About Perception

Because most of our survey gathered value judgments

on the different aspects of Facebook, we can combine

those results with intensity–of–use data to identify the

population’s general opinion of the platform. These

types of insights may potentially be used by Facebook

or other social media platforms to identify how favor-

ably their users perceive them.

Insight 3. Facebook is generally seen as beneficial.

The average net value measured was 4.35 and the me-

dian was 6, showing that Facebook is generally seen

as positive but with low confidence due to a standard

deviation of 33.32.

Insight 4. The least frequent users are in general

what we call “reluctant users”. These are those who

see a net negative value to using Facebook and yet

still use it. Most who use the platform less than once a

week are in this category (see Figure 2, leftmost box).

Understanding How People Weigh the Costs and Benefits of using Facebook

531

Insight 5. Respondents who had deactivated their

Facebook account reported the lowest average net

value seen in Facebook. This can be seen in Figure 3.

Insight 6. People see the most valuable part of

Facebook to be messaging (average 2.59 and median

3 with range -5 to 5). The next most valuable aspect

was “A way to stay connected as you meet people”

with average 2.34 and median 3. Results for each as-

pect can be found in Figure 4.

Insight 7. The aspect of Facebook with the most

negative perceived value was “A way for advertisers

to learn about me” with average -2.32 and median -3.

This suggests people generally do not like that their

data is being used for targeted ads.

6.3 Limitations and Future Work

The survey we developed was not rigorously tested

for reliability and these results could be improved by

measuring the reliability of the responses. One way

this could be accomplished is by executing another

experiment with a slightly adjusted survey: we would

add a second question for all existing value questions

that is similar to the original, but differently worded.

A result showing the originally-asked questions an-

swered in the same way as the rephrased ones would

indicate reliability in the original data set. We could

also administer the same survey twice to a subset of

the respondents with a substantial delay between re-

quests to measure changes over time. Less change

indicates stable responses.

Our survey, while a large sample (n=450), is only

representative of our school’s student body. This does

not map to the demographic composition of Internet

users as a whole, and to measure how an average per-

son acts, we would need to expand the survey to a

representative sample of the general population.

We would also like to know if the survey respon-

dents knew they often acted contrary to their value

judgment: using Facebook even when they claim it

is a negative impact on their lives. By sharing these

results with the survey respondents and following up

after some time, we may be able to see if educating

individuals about their proficiency using their educa-

tion is beneficial.

If the respondents do indeed understand they seem

to behave irrationally, it would be beneficial to learn

what is motivating the reluctant users to exist; perhaps

there are externalities (such as using Facebook as an

identity provider for other websites) that coerce these

users into keeping their Facebook account alive.

Finally, Facebook is not the only social media

platform. It is possible that individuals rely differ-

ently on their value judgments when using other plat-

forms. A similar study could be done with other social

media platforms such as Instagram or Twitter to reveal

how the aspects of each platform are perceived by its

users. This would also allow a deeper understanding

of social media use in general instead of simply one

platform.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Through a survey administered to our university’s stu-

dent body, we were able to answer a few questions

about whether people practice cost–benefit analysis

when choosing how to use a social networking plat-

form. While our results do not show strongly “Yes” or

“No”, we did identify that people who perceive more

benefit in the use of a social networking platform tend

to use it more frequently.

It’s important to note, however, that some people

are “reluctant users”: while they perceive a negative

value to using a social network, they still engage. This

suggests that educating users about the risks and ben-

efits to use of a system may not be sufficient to em-

power them to act on their preferences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Jordan Trachtenberg,

Diane Evans, and Paul Christensen for their help with

survey design, development, deployment, and relia-

bility measures. Thanks also go to Dan Morris, who

was instrumental in helping navigate the institutional

review board process.

REFERENCES

N. S. Good, J. Grossklags, D. K. Mulligan, and J. A. Kon-

stan, “Noticing notice,” Proceedings of the SIGCHI

conference on Human factors in computing systems -

CHI ’07. 2007. DOI 10.1145/1240624.1240720

H. Harkous, K. Fawaz, K. G. Shin, and K. Aberer. 2016.

“PriBots: Conversational Privacy with Chatbots.”

In Proceedings of the 12th Symposium on Usable

Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2016), Denver, CO.

USENIX Association, USA.

H. Harkous, K. Fawaz, R. Lebret, F. Schaub, K. G. Shin, and

K. Aberer. 2018. “Polisis: automated analysis and pre-

sentation of privacy policies using deep learning.” In

ICISSP 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

532

Proceedings of the 27th USENIX Conference on Se-

curity Symposium (SEC’18). USENIX Association,

USA, 531–548.

L. Holtz, K. Nocun, and M. Hansen. “Towards Displaying

Privacy Information with Icons.” In Privacy and Iden-

tity Management for Life (Berlin, Heidelberg, Ger-

many, 2011). Vol 352 of IFIP Advances in Information

and Communication Technology, Springer, pp 338-

348. DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-20769-3 27.

M. Kay and M. Terry, “Textured agreements,” Pro-

ceedings of the Sixth Symposium on Usable Pri-

vacy and Security - SOUPS ’10. 2010. DOI

10.1145/1837110.1837127

P. G. Kelley, J. Bresee, L. F. Cranor, and R. W. Reeder, “A

’nutrition label’ for privacy,” of the 5th Symposium on

Usable Privacy and Security - SOUPS ’09. 2009. DOI

10.1145/1572532.1572538

J. T. Kunze, “Regulating Virtual Realms Optimally: The

Model End User License Agreement,” Northwestern

Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property, vol.

7, no. 1, Fall 2008.

N. Lavesson, P. Davidsson, M. Boldt, and A. Ja-

cobsson, “Spyware Prevention by Classifying End

User License Agreements,” New Challenges in Ap-

plied Intelligence Technologies. pp. 373–382. DOI

10.1007/978-3-540-79355-7 36

V. Mayer-Schonberger, Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in

the Digital Age. Princeton University Press, 2009.

A. M. McDonald, R. W. Reeder, P. G. Kelley, and L. F.

Cranor, “Comparative Study of Online Privacy Poli-

cies and Formats,” Privacy Enhancing Technologies.

pp. 37-55, 2009. DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-03168-7 3.

Mozilla. “Privacy Icons”, published online

June 28, 2011. Accessed March 1, 2020.

https://wiki.mozilla.org/Privacy Icons

S. Staszak, “Privacy Protection Online: Measuring the Gap

of User Understanding.” Senior Thesis. May 2016.

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology.

C. Utz, M. Degeling, S. Fahl, F. Schaub, and T. Holz. 2019.

“(Un)informed Consent: Studying GDPR Consent

Notices in the Field.” In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM

SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communica-

tions Security (CCS ’19). Association for Comput-

ing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 973–990. DOI

10.1145/3319535.3354212

T. Govani and H. Pashley. “Student awareness of the privacy

implications when using Facebook.” Proceedings of

The IEEE - PIEEE. 2007.

R. Dey, Z. Jelveh and K. Ross, “Facebook users have be-

come much more private: A large-scale study,” 2012

IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Comput-

ing and Communications Workshops, Lugano, 2012,

pp. 346-352, DOI 10.1109/PerComW.2012.6197508.

B. Debatin, J. P. Lovejoy, A. Horn, M.A., Brittany N.

Hughes, “Facebook and Online Privacy: Attitudes,

Behaviors, and Unintended Consequences,” Jour-

nal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume

15, Issue 1, 1 October 2009, Pages 83–108, DOI

10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01494.x

A. Vishwanath, W. Xu, and Z. Ngoh, “How people pro-

tect their privacy on Facebook: A cost-benefit view,”

Journal ofthe Association for Information Science and

Technology. 2018. 58. DOI 10.1002/asi.23894

H. R. Lipford, A.Besmer, and J. Watson. “Understanding

Privacy Settings in Facebook with an Audience View.”

UPSEC, 2008, 8, 1-8.

Y. Liu, K. P. Gummadi, B. Krishnamurthy, and A. Mis-

love. “Analyzing facebook privacy settings: user ex-

pectations vs. reality,” In Proceedings of the 2011

ACM SIGCOMM conference on Internet measure-

ment conference (IMC ’11). 2011. 61–70. DOI

10.1145/2068816.2068823

Understanding How People Weigh the Costs and Benefits of using Facebook

533