Knowledge Acquisition on Team Management Aimed at Automation

with Use of the System of Organizational Terms

Olaf Flak

a

University of Silesia in Katowice, 3 Pawla Str., Katowice, Poland

Keywords: Knowledge Acquisition, Team Management Automation, System of Organizational Terms.

Abstract: The aim of the paper is to present a new approach to knowledge acquisition on team management based on

the original methodological concept called the system of organizational terms. The topic of knowledge

acquisition on team management is important because of a lack of development in managerial work

automation in recent years. The scientific problem is how to acquire knowledge on team management in the

holistic, coherent and formalized way and how to represent team management in order to automate it. Both

aspects of this scientific problem are described in this paper. On the one hand there is a common perspective

met in management studies, and on the other hand also the original perspective of the system of organizational

terms was presented. In the paper there is also a short description of a solution for this scientific problem and

examples of previous research verifying the system of organizational terms as a method of knowledge

acquisition on team management and team management representation aimed at automation this area of

human life.

1 INTRODUCTION

After the first age of robotics in mechanical processes

and manufacturing, rapid development of computer

science has given opportunities to make some more

sophisticated work automated (McAfee and

Brynjolfsson, 2016). Especially, the last twenty years

there has been a rapid change of information

technology and an increase of replacing human work

with machines or algorithms. However, it still not

possible to employ a robot on a managerial position

of a team. Why?

The first reason seems to be the characteristics of

managerial work. Team managers do not have the

luxury of standing back or outside of a situation in

which they act. They have to take actions in the

context of the situation. Despite the fact that an

effective teamwork becomes more and more

important for companies (Hoegl and Parboteeah,

2007), managerial actions lead to the consequences

which managers are not able to foresee (Segal, 2011).

A team manager and team members are the warp and

woof of the dynamic fabric of cooperation. They

cannot exist without each other combined together by

managerial actions (Sohmen, 2013).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8815-1185

The second reason consists of three not-existing

conditions: (1) a mutual basis for communication for

an artificial manager and team members (shared

concepts and their meanings) (Clark and Brennan,

1991), (2) prediction methods of human behavior in

teamwork (Klein, Feltovich, Bradshaw and Woods,

2005), (3) a possibility of a real influence of an

artificial manager on team members (Christoffersen

and Woods, 2002).

Both reasons are equally important in the

scientific problem of knowledge acquisition on

managerial work aimed at team management

automation and replacing human managers with

robots (Flak, 2017b).

In this perspective the crucial issue of knowledge

on team management has always come to a simple

question: what does a team manager really do? (Sinar

and Paese, 2016) Therefore, the scientific problem

concerns (1) a succession of managerial actions done

one after another by a team manager, and (2) their

content.

As the result of defining this scientific problem

there is a research question: can it be a holistic,

coherent and formalized methodological concept of

management sciences, which allows to build real

302

Flak, O.

Knowledge Acquisition on Team Management Aimed at Automation with Use of the System of Organizational Terms.

DOI: 10.5220/0010271703020311

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods (ICPRAM 2021), pages 302-311

ISBN: 978-989-758-486-2

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

knowledge on team management aimed at team

management automation?

The aim of this paper is to present the answer to

this research question in the perspective of team

management knowledge acquisition and

representation. In Section 2 there are the literature

review of knowledge acquisition in management

science and team management representation. In

Section 3 there are a description of a methodological

concept called the system of organizational terms

together with research tools which are the main

contribution in the area of knowledge acquisition and

representation. Section 4 contains examples of

building knowledge on team management ready to

use in team management automation. Section 5 is

focused on challenges and further directions of

studies in the field of team management automation.

2 KNOWLEDGE ON TEAM

MANAGEMENT

2.1 Traditional Knowledge Acquisition

Models in Management Science

Knowledge on any issues can concern a few

dimensions of reality named by questioning

pronouns: what, how, who, when, where, why? It is

also possible to distinguish knowledge called

“knowledge: what” and “knowledge: how”. This first

type of knowledge is also named as theoretical

knowledge and the second type is used to be seen as

practical knowledge (El-Sayed, 2003).

In the management studies we can find a wide

range of approaches to creating knowledge on team

management. One of the main division in this context

contains two types of knowledge: tacit and explicit

knowledge (Matos, Lopes, Rodrigues and Matos,

2010). This is the way of creating tacit knowledge as

a result of team work and it is based on an intellectual

capital of team members. Explicit knowledge is

created by the processes taken by team members on

the ground of tacit knowledge.

The second method of knowledge acquisition

presents the model of El-Sayed. This model contains

four stages of creating tacit knowledge changing into

explicit knowledge and on the other way. This

process is extremely dynamic and it proceeds as it

follows. Tacit knowledge on team management

changes into explicit knowledge by the means of

socialisation processes and creating physical things

by teamwork. After this combination explicit

knowledge on organizational reality appears. Then,

by the process of learning, team members acquire

new tacit knowledge which are represented by

socialisation processes and physical things created by

team members etc. This cycle can last forever (El-

Sayed, 2003).

The third way of knowledge acquisition in

management science comes from B. Russel, who

created a term “knowledge by description”. This type

of knowledge acquisition concerns a set of rules

which we combine with a certain physical or mental

thing in the organizational reality. This type of

knowledge can be used in description rather than in

finding fundamental laws of the world (Amijee,

2013). Comparing to tacit and explicit knowledge this

way of knowledge acquisition does not lead to any

innovations and new achievements (Aligica, 2003).

The fourth division of approaches in knowledge

acquisition in management science is presented in

Table 1. This is possible to distinguish two

approaches: functionalism and constructivism

Darmer 2000).

Table 1: Functionalism and constructivism in knowledge

acquisition.

Functionalism Constructivism

Ontology realism relativism

Epistemology narrow

objectivity

subjectivity

Methodology experiments mixed methods

Main question what effective

management

means?

what is

management?

Goal development of

management

cognition of

management

Results normative descriptive

The fifth group of knowledge acquisition

approaches are based on ontological and

epistemological assumptions in organizational reality

research. In these two important areas of every

science there are two main questions: (a) from

ontological point of view – do theories describe the

reality, (b) from epistemological point of view – do

theories lead to the truth? (Kilduff, Mahra and Dunn,

2011). Based on that four approaches to knowledge

acquisition are presented in Table 2.

The sixth approach to knowledge acquisition in

management science is a model of internal and

external knowledge. This model is quite similar to the

model which contained tacit and explicit knowledge,

however, internal and external knowledge is stable in

time (Jaime, Gardoni and Mosca, 2006).

The similar approach is the seventh one presented

by Chalmeta and Wrangel (2008). They define target

knowledge which is a result of tacit and explicit

Knowledge Acquisition on Team Management Aimed at Automation with Use of the System of Organizational Terms

303

knowledge. They claim, similarly to Matos, Lopes,

Rodrigues and Matos (2010), that tacit knowledge is

hidden in people’s minds and explicit knowledge is

placed in organizational documents.

Table 2: Ontological and epistemological questions in

knowledge acquisition.

Epistemology: do the

theories lead to the truth?

Yes No

Ontology:

do the

theories

describe the

reality?

Yes realism

following

paradigms

No

foundatio

nalism

instrumentalis

m

As it can be reckoned from this short review of

approaches to knowledge acquisition on team

management, there are not effective approaches of

building precise knowledge on the organizational

reality which would be holistic, coherent and, what is

more important, formalized in order to use it in team

management automation. Therefore, the original

approach to knowledge acquisition, which meets

these three parameters, was designed and it is

presented in Section 3.

2.2 Dominating Team Management

Representations

As there is a lack of a stable and reliable approach to

knowledge acquisition in management science, the

same situation concerns team management

representation. The view of managerial work has

been changed since the scientific management was

born. At the beginning of 20

th

century the picture of a

manager was defined by his classical functions (set of

activities), such as a planner, an organizer, a

motivator and a controller (Fayol, 1916). 50 years

later a view of a manager was dominated by two

approaches and it has lasted until today.

Firstly, in 1964 Koontz and O'Donneil (1964)

launched a discussion on the meaning of managerial

skills. A few years later an approach in which

managerial work was represented by managerial

skills was proposed (Katz, 1974). The managerial

skill was than defined as an ability to work effectively

as a team manager in order to build cooperative effort

within the team (Katz, 1974). A dominating typology

of managerial skills divides skills into 3 groups:

technical, interpersonal and conceptual. Technical

skills were regarded as most important for

supervisors, interpersonal skills for middle managers,

and conceptual skills for executives (Kaiser, Craig,

Overfield and Yarborough, 2011). This approach to

skills has been developed over decades and one of the

latest typologies contains such skills as critical

thinking, problem solving, an ability to organize data,

conceptual thinking, evaluating ideas, persuasive

skills etc. (Ullah, Burhan and Shabbir, 2014).

Secondly, in 1980 Mintzberg concluded that the

managerial work in a team can be described in terms

of 10 roles within interpersonal, informational and

decisional areas which were common to the work of

all types managers. He defined a managerial role as

an area of job activities which is undertaken by a

manager (Mintzberg, 1980). Mintzberg introduced to

the management science a typology of managerial

roles which contains such roles: a figurehead, a

leader, a liaison, a monitor, a disseminator, a

spokesman, an entrepreneur, a disturbance handler, a

resource allocator, a negotiator (Mintzberg, 1980).

Other researchers of team management proposed

other divisions of roles, such as a leader, a peer, a

conflict solver, an information sender, a decision

maker, a resources allocator, an entrepreneur, a

technician (Pavett and Lau, 1982) or an explorer, an

organizer, a controller, an adviser (McCan and

Margerison, 1989).

Managerial skills and managerial roles have

influenced scientists and practitioners so much, that

most of research on managerial work was designed as

a research either on managerial skills or managerial

roles. The examples of published results of such

studies during last 50 years:

The nature of the skills involved in managerial

jobs; Managers in 32 manufacturing firms in the

Madison-Milwaukee industrial area (McLennan,

1967).

Measuring the process of managerial

effectiveness in relations with specific behaviour and

activities characteristic of managerial work;

Managers from 6 companies in the US (Morse and

Wagner, 1978).

Importance of Mintzberg’s roles across several

different functional areas, including a relatively

ignored segment of the managerial population—

namely, the general manager; Managers and

executives representing a wide variety of private

sector service and manufacturing firms in southern

California (Pavett and Lau, 1982).

Investigation on the managerial roles of the chief

information officer (CIO) based on Mintzberg’s

classic managerial role model; Companies randomly

selected from the 1991 listing of Fortune 1000

companies (Grover, Jeong, Kettinger and Lee, 1993).

Relationships between creativity style, as

measured by the Kirton Adaption Innovation

ICPRAM 2021 - 10th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods

304

Inventory (KAI) and the self and other ratings on a

360-degree feedback instrument, the Management

Skills Profile (MSP); Managers who were mid-career

MBA students attending a part-time evening

programme in a medium-sized south-eastern state

university in the United States (Buttner, Gryskiewicz

and Hidore, 1999).

Employees’ attitudes and performance as

measures of managerial effectiveness. Middle

managers in numerous US facilities of a large, high-

technology, non-traditional firms (Shipper and Davy,

2002).

Perception of the role of the manager which

contributed to changes in everyday managerial

practices. CEO of the companies employed between

slightly fewer than 2,000 persons to almost 15,000

persons and the combined market value of the three

listed companies exceeded US$12 billion at the time

of study (Tengblad, 2006).

Female and male managers communication

skills; Managers of an organization located in the San

Francisco, Bay Area (Kaifi and Noori, 2011).

Global management skill sets and capabilities

among multinational corporations; Senior executives

from multinational organizations in North America

and India (Ananthram and Nankervis, 2013).

Status of managerial skills, features of

organisational climate and the interaction of

managerial skills with organisational climate;

Managers in educational service sector (Vandana and

Dhull, 2014).

Importance for each managerial role in using

managerial skills; MBA students (Ullah, Burhan and

Shabbir, 2014).

Importance of values and skills of managers;

Senior lean experts employed by a single Dutch

medium-sized management (van Dun, Hicks and

Wilderom, 2015).

Management skills of retail companies; Team

leaders in retail companies (Mihalcea and Mihalcea,

2015).

Actions of great leaders, the definition of an

effective leader, factors need to be considered to

identify the right leaders who can successfully

transition into higher-level roles; Team leaders in 300

organizations, 20 industries and 18 countries (Sinar

and Paese, 2016).

Based on the review presented above, it is

possible to draw a conclusion that managerial skills

and managerial roles are traditional theoretical

concepts commonly used to represent team

management. However, these terms still do not

recognize what a team manager really does (Sinar and

Paese, 2016). So that, it is not possible to recognize

(1) a succession of managerial actions done one after

another by a team manager, and (2) their content. The

answer to this question is presented in Section 3 and

it is the main contribution in this paper to the problem

of knowledge acquisition on team management aimed

at automation.

3 THE SYSTEM OF

ORGANIZATIONAL TERMS

METHODOLOGY

3.1 Knowledge Acquisition based on

the System of Organizational

Terms

The first aspect of the scientific problem mentioned

in Section 1 concerns achieving a precise and

coherent view of team managerial work which could

be efficiently used in team management automation.

There comes a challenge, how to represent a

succession of different types of managerial actions

one after another done by a team manager. The

pioneering answer to this challenge is the system of

organizational terms, which is a complex of

ontological and epistemological aspects designed for

managerial action patterns research (Flak, 2013; Flak

2020).

The ontological assumption of the system of

organizational terms is that every fact in the

organizational reality can be represented by the

organizational term (Zalabardo, 2015). The

organizational term is a symbolic object which can be

used as an element of the organizational reality model

(Rios, 2013) and it is a close analogy to a physical

quantity in the SI unit (length, mass, time etc.).

It is assumed that the organizational terms are

abstract objects which are used to represent the facts

which appear in the organizational reality. The

features of the organizational term, on the one hand,

come from its definition and, on another hand, derives

from causal relations or occurrence relations with

other organizational terms (Backlund, 2000).

The philosophical foundation of the system of

organizational terms is based on Wittgenstein’s

philosophy: his theory of facts (the only beings in the

world) and “states of facts” (Brink and Rewitzky,

2002). According to this approach managerial actions

can be organised by events and things. Specifically,

as shown in Figure 1, each event and thing have the

label n.m, in which n and m represent a number and a

version of a thing, respectively. Event 1.1 (set 1.1)

Knowledge Acquisition on Team Management Aimed at Automation with Use of the System of Organizational Terms

305

causes thing 1.1 (goal 1.1), which in turn releases

event 2.1 (generate 2.1) that creates thing 2.1 (idea

2.1). Thing 1.1 (goal 1.1) simultaneously starts event

3.1 (describe 3.1) which creates thing 3.1 (task 3.1).

Then, thing 3.1 (task 3.1) generates the second

version of the first event, i.e. event 1.2 (goal 1.2). So,

the managerial action structure consist of, e.g. event

1.1 and thing 1.1 (in the system of organizational

terms called a derivative and primal organizational

term, respectively).

Figure 1: Fundamental structure of managerial actions.

According to the logical division, organizational

terms are divided into two classes: primal and

derivative organizational terms. Facts, which are

things (primal organizational terms) in the

organizational reality, represent resources (Barney,

1991). Facts, which are events (derivative

organizational terms) in the organizational reality,

represent processes in the organization (Brajer-

Marczak, 2016). By the same token, the system of

organizational terms combines the resource approach

and the process approach in the management science.

It combines processes which effect in resources. In

pairs they create managerial actions.

Features of managerial actions are grouped in

time, content and human relations domains. They

show how much two managerial actions differ from

one another or one managerial action differs from

itself in the function of time.

Such an approach to ontology of team managerial

work lets represent all managerial activities by

standardized features vectors with data grouped in

time and content (Flak, Yang and Grzegorzek, 2017).

Comparing this approach to the team management

representation described in Section 2 it is possible to

assume that the answer to the question “what does a

team manager really do?” seems to be hidden in the

relation between managerial roles and managerial

skills. In order to play managerial roles a team

manager should have some managerial skills (Pavett

and Lau, 1983). It results in understanding playing

managerial roles within their managerial skills by

day-to-day activities of managers effects in the

managerial actions, which these managers make.

Therefore, the managerial action can be defined as a

real activity, which a manager does in order to play a

managerial role and have a certain managerial skill

(Flak, Yang and Grzegorzek, 2017).

3.2 Research Tools Aimed at Building

Knowledge on Team Management

The second aspect of the scientific problem

mentioned in Section 1 concerns focusing on the

content of the managerial actions. This challenge

needs a special method of gathering data on team

managerial actions. The data should be recorded in a

way, which allows to represent a team manager by

managerial actions, that take place in a team, which

he leads. That is why, the content of managerial

actions should be represented by a scalable vector.

The best way of recording team managerial actions by

research tools is using online management tools or

other electronic devices, which a team manager and

his team members use during day-to-day work (Flak,

2017a). The innovative tools of recording information

in time and content domains are embedded in the

TransistorsHead.com platform, which is a complex of

online management tools designed for a modern and

contemporary method of time and motion study.

In order to get such data about managerial actions,

one of the epistemological assumption of the system

of organizational terms is, that the main research

method is an objective long-term observation

(Midgley, 2003). The measurement of a managerial

action is defined as an assignment of a certain set of

values to a certain set of managerial action features

(Mari, 2005). It is designed so that the features of any

managerial action can be measured by a research tool

which gathers data about the primal organizational

term (a thing in the fundamental structure of a

managerial action – Figure 1 – which means a

resource in the organizational reality) (Chopraa and

Gopal, 2011).

As it is shown in Figure 1, when a team manager

sets a goal (a managerial action represented by event

1.1 - setting 1.1 and thing 1.1 - goal 1.1), the research

tool called “Goaler” records features of goal 1.1 in

time and content domains. If later (e.g. after

describing a task – describing 1.1 and task 1.1) this

team manager does the next setting of the same goal,

he launches the next managerial action. Then the

features of this managerial action are changed and

represent the second version of this managerial action

(setting 1.2 and goal 1.2). The difference between

managerial action features of goal 1.2 and goal 1.1.

let do reasoning on the events which happened in this

period of time (Flak, 2017a).

ICPRAM 2021 - 10th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods

306

Table 3: TransistorsHead.com structure.

Name of managerial

tools in

TransistorsHead

Number of

managerial

actions

Name of

managerial

actions

set goals 1 set goals

describe tasks 2 describe tasks

generate ideas 3 generate ideas

specify ideas 4 specify ideas

create options 5 create options

choose options 6 choose options

check motivation 7

check

motivation

solve conflicts 8 solve conflicts

prepare meetings 9

prepare

meetings

explain problems 10

explain

problems

Table 4: Functions of online management tools.

Tool Application of the tool during team work

Set goals

Agreeing on the goals of the project,

actions to be taken, etc. (what is the

overall goal of the project?).

Describe

tasks

Describing tasks that will have to be

performed in order to achieve the overall

goals.

Generate

ideas

Generating ideas (brainstorming) about

performing the tasks (who, how, when,

where) and solving potential problems.

Specify

ideas

Describing in detail the ideas and

solutions.

Create

options

Creating options for decision making

(deciding which options are the best and

which options the team will choose as the

final ones).

Choose

options

Selecting and deciding which options will

be chosen as the most beneficial for the

participants according to criteria that

determine this (what is the most

important aspect/criterium).

Check

motivation

Checking the level of motivation of the

team members according to Maslow’s

theory of basic needs.

Solve

conflicts

Analyzing reasons for potential conflicts

among the team members, coming up

with possible solutions to these conflicts.

Prepare

meetings

Preparing agenda for a meeting based on

the law of demand and supply, known in

economy. The agenda allows for using

the potential in the team and knowledge

of participants.

Explain

problems

Explaining business problems or tasks by

analysis of keywords in sentences.

From the theoretical point of view online

management tools have such features:

according to the idea of an „unit of behaviour”

(Curtis, Kellner and Over, 1992) every online

management tool tracks and records one specific team

managerial action,

when a team manager uses any online

management tool it is equal a process which results in

a resource, respectively (Flak, 2017a),

every management tool is designed for recording

a certain team managerial action (Flak, 2017a).

Such online management tools were implemented

as online management tools called

TransistorsHead.com available at the website

browser. This platform was designed by the author of

this paper and it consists of 10 different tools to track

10 separate managerial actions (Flak, Hoffmann-

Burdzińska, Yang, 2018). Table 3 contains the names

of online managerial tools, their numbers (which are

necessary to read the Figures 2, 3, 4), and names of

managerial actions. In Table 4 there are functions of

the online management tools.

4 EXAMPLES OR RESEARCH

RESULTS

4.1 Knowledge on Succession of

Managerial Actions

In the last few years there were a dozen experiments

aimed at checking if the system of organizational

terms can be a new knowledge acquisition method

useful in team management automation.

Concerning the first aspect of the scientific

problem mentioned in Section 1 (a succession of

managerial actions done one after another by a team

manager) it is possible to show results of one of such

experiments. In 2019 students of Human Relations

Management at the Faculty of Psychology at the

University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland, were to

conduct a given project from an idea to a final

presentation. The students were working in teams of

4-5, every one of which had a defined manager who

was leading it.

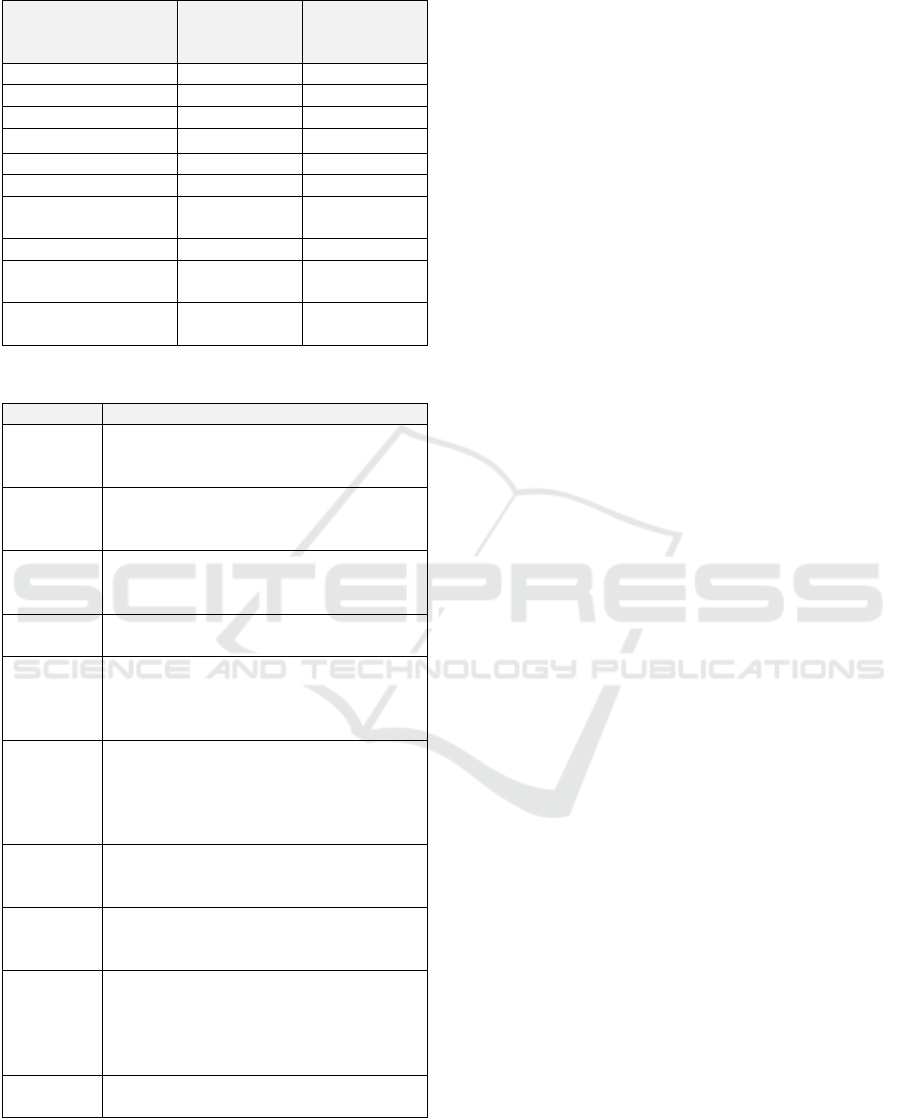

Firstly, Table 5 shows how many separate

managerial actions were taken by every manager,

when they started and finished their work and how

much time their teamwork took in this project.

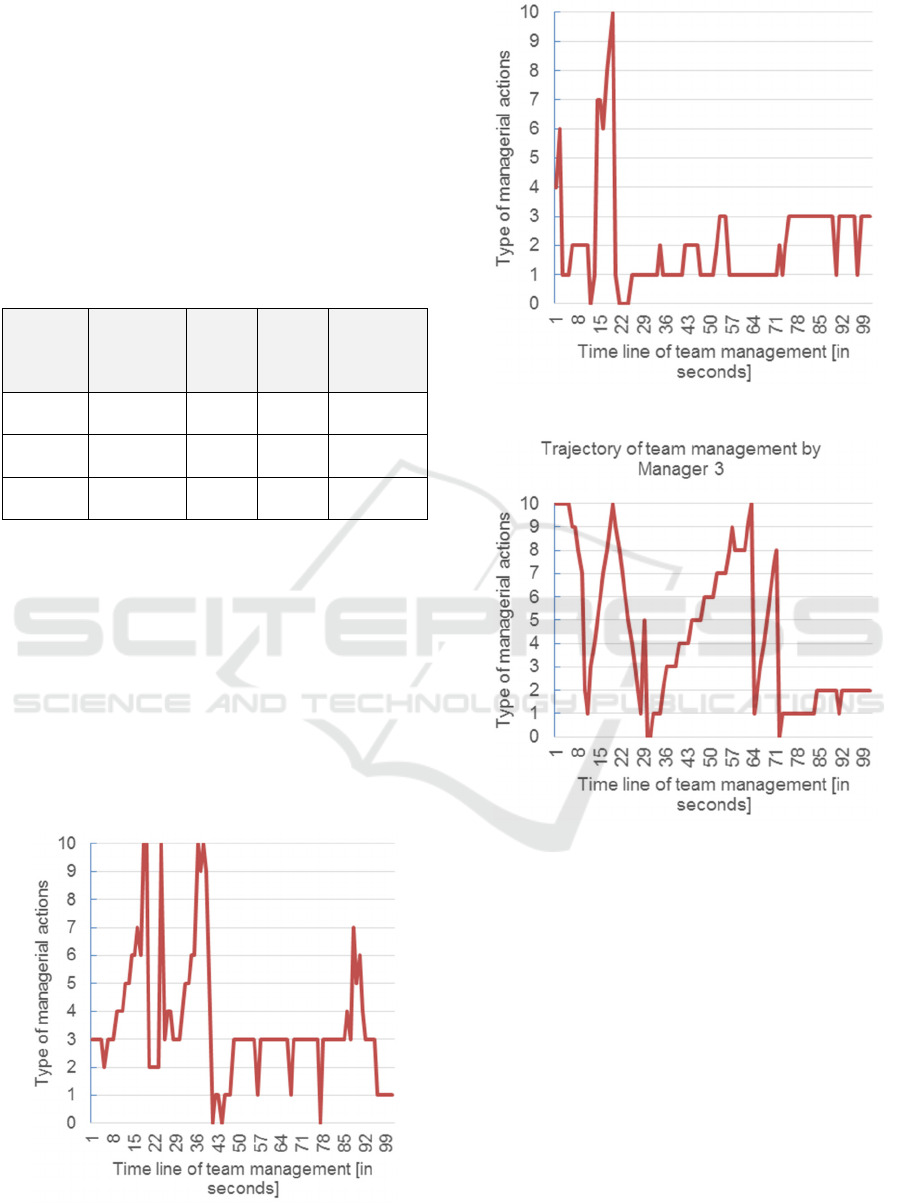

Secondly, managers were managing teams by

online management tools that recorded their

managerial actions. Owing to the fact, it is possible to

present the trajectory of 10 recorded managerial

actions on a timeline in histograms of team

management. The trajectories of all managers are

Knowledge Acquisition on Team Management Aimed at Automation with Use of the System of Organizational Terms

307

presented in Figures 2 to 4, respectively. Numbers in

types of managerial actions mean: 0 – no managerial

action, 1 – set goals, 2 – describe tasks, 3 – generating

ideas, 4 – specifying ideas, 5 – creating option s, 6 –

choosing options, 7 – checking motivation, 8 –

solving conflicts, 9 – preparing meetings, 10 –

explaining problems. The figures shows 100 chosen

moments of managerial actions recorded

approximately in the middle of the team work period

shown in Table 5.

Table 5: General statistics on managerial actions taken by

managers.

Manager

no.

Total

number of

managerial

actions

Date of

start

dd.mm

hh:mm

Date of

finish

dd.mm

hh:mm

Period of

teamwork

(in

seconds)

Manager

1

293

14.05

10:55

28.05

10:20

1207523

Manager

2

328

14.05

10:53

28.05

21:57

1249484

Manager

3

446

14.05

10:53

01.06

18:13

1581591

As it can be recognized, all team managers had

different trajectory of their managerial actions even

than they were working on the same projects. The

succession of managerial actions done one after

another by every team manager was completely

different. This shows that the system of

organizational terms together with special

measurements tools (which is separate problem and

area of design) lets us solve the first aspect of the

scientific problem shown in Section 1. We can

achieve a knowledge on a succession of managerial

actions done one after another by a team manager.

Figure 2: Trajectory of team management by Manager 1.

Figure 3: Trajectory of team management by Manager 2.

Figure 4: Trajectory of team management by Manager 3.

4.2 Knowledge on Managerial Actions

Content

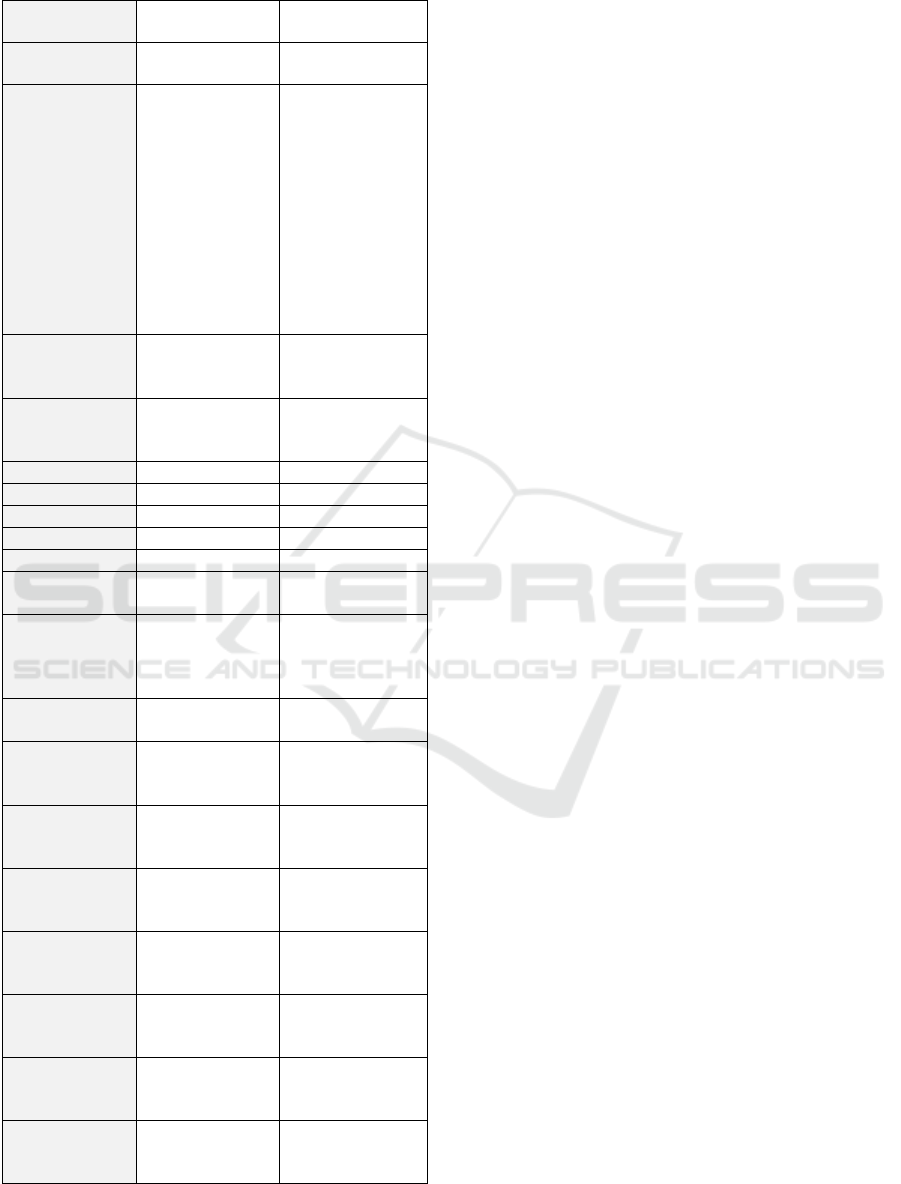

Concerning the second aspect of the scientific

problem mentioned in Section 1 (content of

managerial actions) as an example can be the results

of the experiment which was conducted in 2018.

Business students from one of the universities of

applied sciences in Helsinki took part in it. They were

divided into seven teams, each of which consisted of

five members and a team manager. The teams got the

task of preparing a training program for teachers of

their university (Flak, 2018).

In Table 6 there is content of a goal set by one of

the participants of the research in the first and the

second

version.

According

to

Figure

1,

the

manager

ICPRAM 2021 - 10th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods

308

Table 6: Content of a goal in two following versions.

Number of a

goal

1 1

Version of a

goal

1 2

Future vision

after achieving

a goal

We employ

young, ambitious

people to new

project groups

called C-LAB

and to new

projects of a

company. A

brand of our

company is well

known on the

market.

We employ young

and ambitious

employees. We

have no project

groups called C-

LAB.

Name of a goal

Workshops for

teenagers

Workshops for

teenagers

Way of setting a

time of

achieving a goal

period period

hours 0 0

days 0 0

weeks 0 0

months 0 5

years 1 0

Measurer 1

Finding cheap

employees

Low salary for

employees

Measurer 2

Increase of

peoples

knowledge on

animation

Middle

experience of

participants

Measurer 3

3 innovations in

social media

1 innovation in

social media

Measurer 4

Employment of

new workers to

project groups

New

advertisement in

radio

How much is

this goal real to

achieve?

Mostly yes Completely

How much does

this goal belong

to your duties?

Partly Mostly no

What is the

business area of

this goal?

Human resources

management

Human resources

management

Is this goal

shortterm or

longterm?

longterm shortterm

Is this goal

operational or

strategic?

operational strategic

Who is

responsible for

this goal?

My team My team

set this goal 1.1. and then reset it – we have a goal 1.2.

How this goal changed during the time of team

management (which happened between the first and

the second version) it is shown in Table 6. This shows

that the system of organizational terms lets us also

solve the second aspect of the scientific problem

presented in Section 1. We record not only a

succession of managerial actions but also a content of

every managerial action. This gives us knowledge

what are parameters of managerial actions in their

feature vectors.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The system organizational terms as a method of

knowledge acquisition on team management can help

to solve the scientific problem of getting real

knowledge what the manager really does. In this

concept the source of cognition is an observation of

the organisational reality in independent of the

cognition subject.

It is assumed that the source of information is the

fact which occurs in the organisational reality. That

information can be converted into data, while data can

be turned into knowledge about organisational reality.

Therefore knowledge about the organisational reality

can be largely objective. It is normative knowledge

and it is represented by sentences formulated in a

language.

As it was shown in Section 4, both succession of

team managerial actions and their content can be

capture by using the system of organizational terms

together with dedicated measurement tools. This type

of knowledge acquisition is the first step to answer to

the research question “what does the team manager

really do?” aimed at automation of these managerial

actions.

The next step towards team management

automation and effective replacement human

managers with robots is to implement some pattern

recognition techniques and machine learning

techniques which could lead to launch automated

managerial actions in team management.

REFERENCES

Aligica, P. D. (2003). Prediction, Explanation and the

Epistemology of Future Studies. Futures, 35, 1027-

1040.

Amijee, F. (2013). The Role of Attention in Russell’s

Theory of Knowledge. British Journal for the History

of Philosophy, 21(6), 1175-1193.

Knowledge Acquisition on Team Management Aimed at Automation with Use of the System of Organizational Terms

309

Ananthram, S., & Nankervis, A. (2013). Global managerial

skill sets, management development, and the role of

HR: an exploratory qualitative study of north American

and Indian managers. Contemporary Management

Research, 9(3), 299-322.

Backlund, A. (2000). The definition of system. Kybernetes,

29(4), 444-451.

Barney, J.B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained

competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1),

99-120.

Brajer-Marczak, R. (2016). Elements of knowledge

management in the improvement of business processes.

Management, 20(2), 242-260.

Brink, C. & Rewitzky, I. (2002). Three dual ontologies.

Journal of Philosophical Logic, 31(6), 543-568.

Buttner, E. H., Gryskiewicz, N., & Hidore, S. C. (1999).

The Relationship between styles of creativity and

managerial skills assessment. British Journal of

Management, 10, 228-238.

Chalmeta, R., & Wrangel, R. (2008). Methodology for the

Implementation of Knowledge Management Systems.

Journal of the American Society for Information

Science and Technology, 59(5), 742-755.

Chopraa, P. K., & Gopal, K. K. (2011). On the science of

management with measurement. Total Quality

Management, 22(1), 63-81.

Christoffersen, K., & Woods, D. D. (2002). How to make

automated systems team players. Advances in Human

Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research, 2,

1-12.

Clark, H. H., & Brennan, S. E. (1991). Grounding in

communication. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D.

Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on Socially Shared

Cognition (pp. 127-149). American Psychological

Association.

Curtis, B., Kellner, M., & Over, J. (1992). Process

modelling. Communications of the ACM, 35(9), 75-90.

Darmer, P. (2000). The subject(ivity) of management.

Journal of Organizational Change Management, 13(4),

334-351.

El-Sayed, A. Z. (2003). What can Methodologist Learn

from Knowledge Management? The Journal of

Computer Information Systems, 43(3), 109-117.

Fayol, H. (1916). Administration industrielle et generate.

Paris: Dunod.

Flak, O. (2013). Theoretical foundation for managers’

behavior analysis by graph-based pattern matching.

International Journal of Contemporary Management,

12(4), 110-123.

Flak, O. (2017a). Methodological foundations of online

management tools as research tools. In: V. Benson, F.

Filippaios (Eds.), Proceedings of the 16th European

Conference on Research Methodology for Business and

Management Studies ECRM2017, 113-121.

Flak, O. (2017b). Selected Problems in Team Management

Automation. Acta Universitatis Nicolai Copernici -

Zarzą

dzanie, 4, 187-198, ISSN 1689-8966

Flak, O. (2020). System of organizational terms as a

methodological concept in replacing human managers

with robots. W: Advances in information and

communication. Proceedings of the 2019 Future of

Information and Communication Conference (FICC),

471-500.

Flak, O., Hoffmann-Burdzińska, K., & Yang, C. (2018).

Team Managers Representation and Classification

Method based on the System of Organizational Terms.

Results of the Research. Journal of Advanced

Management Science, 6(1), 13-21.

Flak, O., Cong, Y., & Grzegorzek, M. (2017). Action

Sequence Matching of Team Managers. In:

Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on

Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods

ICPRAM, February 24-26, Porto, Portugal, 386-393.

Grover, V., Jeong S-R., Kettinger, W.J., & Lee, C.C.

(1993). The chief information officer: a study of

managerial roles. Journal of Management Information

System, 10(2), 107-130.

Hoegl, M., & Parboteeah, K.P. (2007). Creativity in

innovative projects: how teamwork matters. Journal of

Engineering and Technology Management, 24(1–2),

148-166.

Jaime, A., Gardoni, M., & Mosca, J. (2006). From Quality

Management to Knowledge Management in Research

Organisations. International Journal of Innovation

Management, 10(2), 197-215.

Kaifi, B. A., & Noori, S. A. (2011). Organizational

behavior: a study on managers, employees, and teams.

Journal of Management Policy and Practice, 12(1), 88-

97.

Kaiser, R. B., Craig, S. B, Overfield, D. V., & Yarborough,

P. (2011). Differences in managerial jobs at the bottom,

middle, and top: a review of empirical research. The

Psychologist-Manager Journal, 14(2), 76-91.

Katz, R. L. (1974). Skills of an effective administrator.

Harvard Business Review, 52(5), 90-102.

Kilduff, M., Mahra, A., & Dunn, M. B. (2011). From Blue

Sky Research to Problem Solving: A Philosophy of

Science Theory of New Knowledge Production.

Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 297-317.

Kimberley, A., & Flak, O. (2018). Culture, Communication

and Performance in Multi and Mono-Cultural Teams:

Results of a Study Analysed by the System of

Organisational Terms and Narrative Analysis. In:

Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on

Research Methodology for Business and Management

Studies ECRM2018, 199-207.

Klein, G., Feltovich, P. J., Bradshaw, J. M., & Woods, D.

D. (2005). Common ground and coordination in joint

activity. In W. R. Rouse & K. B. Boff (Eds.),

Organizational Simulation (pp. 139-178). John Wiley

& Sons.

Koontz, H., & O'Donneil, C. (1964). Principles of

management. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mari, L. (2005). The problem of foundations of

measurement. Measurement, 38(4), 259-266.

Matos, F., Lopes, A., Rodrigues, S., & Matos, N. (2010).

Why Intellectual Capital Management Accreditation is

a Tool for Organizational Development? Electronic

Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(2), 235-244.

ICPRAM 2021 - 10th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods

310

McAfee, A., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2016). Human work in the

robotic future: Policy for the age of automation.

Foreign Affairs, 95(4), 139-150.

McCan, D., & Margerison, Ch. (1989). Managing high-

performance teams. Training & Development Journal,

10, 53-60.

McLennan, K. (1967). The manager and his job skill.

Academy of Management Journal, 10(3), 235-245.

Midgley, G. (2003). Science as systemic intervention: some

implications of systems thinking and complexity for the

philosophy of science. Systemic Practice and Action

Research, 16(2), 77-97.

Mihalcea, A., & Mihalcea, D. (2015). Management skills

assessment using 360° feedback - MSF 360. Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 187, 318-323.

Mintzberg, H. (1980). The nature of managerial work. New

York: Prentice-Hall.

Morse, J. J., & Wagner, F. R. (1978). Measuring the process

of managerial effectiveness. Academy of Management

Journal, 21(1), 23-35.

Pavett, C. M., & Lau, A. W. (1982). Managerial roles,

skills, and effective performance. Academy of

Management Proceedings, 95-99.

Pavett, C. M., & Lau, A. W. (1983). Managerial work: the

influence of hierarchical level and functional specialty.

Academy of Management Journal, 26(1), 170-177.

Rios, D. (2013). Models and modeling in the social

sciences. Perspectives on Science, 21(2), 221-225.

Segal, S. (2011). A Heideggerian perspective on the

relationship between Mintzberg’s distinction between

engaged and disconnected management: the role of

uncertainty in management. Journal of Business Ethics,

103, 469-483.

Shipper, F., & Davy, J. (2002). A model and investigation

of managerial skills, employees’ attitudes, and

managerial performance. The Leadership Quarterly,

13, 95-120.

Sinar, E., & Paese, M. (2016). The new leader profile.

Training Magazine, 46, 46-50.

Sohmen, V.S. (2013). Leadership and teamwork: Two sides

of the same coin. Journal of Information Technology

and Economic Development, 4(2), 1-18.

Tengblad, S. (2006). Is there a ‘New Managerial Work’? A

comparison with Henry Mintzberg’s Classic Study 30

years later. Journal of Management Studies, 43(7),

1437-1461.

Ullah, F., Burhan, M., & Shabbir, N. (2014). Role of case

studies in development of managerial skills: evidence

from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Business Schools. Journal

of Managerial Sciences, 8(2), 192-207.

Ullah, F., Burhan, M., & Shabbir, N. (2014). Role of case

studies in development of managerial skills: evidence

from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Business Schools. Journal

of Managerial Sciences, 8(2), 192-207.

van Dun, D. H., Hicks, J. N., & Wilderom, P. M. (2015).

Values and behaviors of effective lean managers:

Mixed-methods exploratory research.

European

Management Journal, 35(2), 174-186.

Vandana, B. K., & Dhull, P. I. (2014). An exploration of

managerial skills and organizational climate in the

educational services. Journal of Services Research,

4(1), 141-160.

Zalabardo, J. (2015). Representation and reality in

Wittgenstein's Tractatus. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Knowledge Acquisition on Team Management Aimed at Automation with Use of the System of Organizational Terms

311