Demonstrating GDPR Accountability with CSM-ROPA:

Extensions to the Data Privacy Vocabulary

Paul Ryan

1,2 a

and Rob Brennan

1b

1

ADAPT Centre, School of Computing, Dublin City University, Glasnevin, Dublin 9, Ireland

2

Uniphar PLC, Dublin 24, Ireland

Keywords: Data Protection Officer, RegTech, Register of Processing Activities, Semantic Web.

Abstract: The creation and maintenance of a Register of Processing Activities (ROPA) are essential to meeting the

Accountability Principle of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). We evaluate a semantic model

CSM-ROPA to establish the extent to which it can be used to express a regulator provided accountability

tracker to facilitate GDPR/ROPA compliance. We show that the ROPA practices of organisations are largely

based on manual paper-based templates or non-interoperable systems, leading to inadequate GDPR/ROPA

compliance levels. We contrast these current approaches to GDPR/ROPA compliance with best practice for

regulatory compliance and identify four critical features of systems to support accountability. We conduct a

case study to analyse the extent that CSM-ROPA, can be used as an interoperable, machine-readable

mediation layer to express a regulator supplied ROPA accountability tracker. We demonstrate that CSM-

ROPA can successfully express 92% of ROPA accountability terms. The addition of connectable vocabularies

brings the expressivity to 98%. We identify three terms for addition to the CSM-ROPA to enable full

expressivity. The application of CSM-ROPA provides opportunities for demonstrable and validated GDPR

compliance. This standardisation would enable the development of automation, and interoperable tools for

supported accountability and the demonstration of GDPR compliance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Organisations are facing significant challenges in

meeting the accountability principle of the GDPR.

The GDPR prescribes that organisations create and

maintain a Register of Processing Activities (ROPA),

which is a comprehensive record of their personal

data processing activities. Aside from being a legal

obligation on organisations, a ROPA is an internal

control tool and, is a way to demonstrate an

organisation's compliance with the GDPR.

A review of the ROPA practices of organisations

shows that they face challenges with maintaining their

ROPA documents. We review these approaches and

identify the inherent weaknesses and challenges that

organisations face. We determine what best practice

for GDPR compliance is. We provide a case study to

demonstrate the expressiveness of our mediation layer

CSM-ROPA. We semantically map the ROPA section

of a regulator supplied accountability framework to

support GDPR accountability.

a

https://orcid.org/

0000-0003-0770-2737

b

https://orcid.org/

0000-0001-8236-362X

In section 2, we discuss the accountability

principle of the GDPR. We identify the internal

bodies such as the board of the organisation, and

external entities such as data subjects, business

partners, data protection regulators and certification

bodies to whom GDPR compliance is demonstrable.

We discuss the benefits and sanctions that accrue

dependant on the organisation's ability to demonstrate

their GDPR compliance.

In section 3, we review the available literature to

identify best practice for the demonstration of GDPR

regulatory compliance and identify the key features

that need to be present for a successful regulatory

compliance framework. In section 4, we review the

current approaches taken by organisations to create

and maintain their ROPAs, and we discuss the

challenges faced by organisations in meeting the

accountability principle of the GDPR. In Section 5,

we discuss the approach that organisations should be

taking to go beyond a paper-based strategy for ROPA

compliance. We discuss the steps that organisations

Ryan, P. and Brennan, R.

Demonstrating GDPR Accountability with CSM-ROPA: Extensions to the Data Privacy Vocabulary.

DOI: 10.5220/0010390505910600

In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2021) - Volume 2, pages 591-600

ISBN: 978-989-758-509-8

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

591

should be taking to engage and apply the best

practices to move to a machine-readable ROPA to

support accountability.

In section 6, we introduce our Common Semantic

Model of the Register of Processing Activities (CSM-

ROPA), developed to map regulator supplied ROPA

templates semantically. We describe the role of CSM-

ROPA as a mediation layer between the processing

activities layer of the organisation and the reporting

and monitoring layer facilitating the automation of

ROPA accountability compliance verification. Our

research question asks to what extent can CSM-

ROPA model the ROPA section of a regulator

supplied accountability framework, to assist

organisations in meeting the accountability principle

of the GDPR. The remainder of the paper will

introduce a case study where we deploy CSM-ROPA

to facilitate the interoperable exchange of information

to enable compliance verification as set-out in the

accountability framework.

The contributions of this paper are the

demonstration of the expressiveness of CSM-ROPA

to facilitate GDPR supported accountability. We

identify vocabularies that can be linked to the Data

Privacy Vocabulary (DPV) to improve expressivity,

and we identify several terms for inclusion in the

DPV. The positive outcome of this research indicates

that with a small number of additions to CSM-ROPA,

it is possible to support machine to machine

accountability compliance verification for the

creation and maintenance of ROPAs.

2 WHAT IS ACCOUNTABILITY

UNDER THE GDPR?

Accountability is an expression of how an

organisation must display "a sense of responsibility

and a willingness to act in a transparent, fair and

equitable way" (Bovens, 2007), moreover, "the

obligation to explain and justify conduct' (Bovens,

2007). The GDPR places accountability as one of the

seven fundamental principles of the regulation and

requires that an organisation is responsible for and

must demonstrate compliance with all principles of

the GDPR (Ryan, 2020a). Organisations must put in

place "appropriate and effective measures to put into

effect the principles and obligations of the GDPR and

demonstrate on request" (GDPR, Art 5). This

regulation places an obligation on organisations, to

demonstrate proof related to whether, how and how

well the organisation protects personal data.

Considering such a significant obligation,

organisations must fundamentally rethink the way

they store and process personal data on an enterprise-

wide level (Labadie, 2019).

The purpose of accountability is not just the

evaluation of compliance with statutory obligations.

An accountable organisation can demonstrate how

they respect the privacy of their data subjects, i.e. the

subjects of the processing of personal data. Hence the

organisation has several audiences for the demonstra-

tion of compliance. Internally, the organisation must

demonstrate that it is operating in an accountable

manner to its corporate board and employees; they

need to put internal organisational privacy and

information management programs in place. The

provision would include the implementation of

internal measures and procedures, putting into effect

existing data protection principles, ensuring their

effectiveness and the obligation to prove this should

data protection authorities request it.

Similarly, the organisation has obligations to

demonstrate compliance to external stakeholders

such as individuals, business partners, shareholders

and civil society bodies representing individuals and,

to Data Protection Authorities. The organisation may

also need to demonstrate compliance with a

certification body as part of a code of conduct or a

standardised certification accountability framework

(GDPR Art 42). The role of such external

certifications, seals and codes of conduct have the

benefit to support accountability when accompanied

by some form of external validation, which ensures

both verification and demonstration (CIPL,2018).

The benefits of organisational accountability

cannot be overstated (CIPL2018). Accountability

gives organisations a solid framework for compliance

with applicable legal requirements, for protecting

data subjects from privacy harms and for building

trust in the organisations' ability to engage in the

responsible use of data. Importantly, accountability

provides an approach to data protection that is

transparent, risk-based, technology-neutral and

future-proof (CIPL, 2018). Implementation of

accountability increases trust in the operations of the

organisation. It ensures that the organisation is

equipped to handle new challenges to data protection

law and practice, regardless of advances in

technology or changes in the behaviours or

expectations of individuals and provides them with

the necessary flexibility and agility to customise their

data privacy management programs. Successfully

embedding accountability will enhance the reputation

of the business that it can be trusted with personal data

(CIPL,2018).

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

592

The alternative to the implementation of a robust

accountability framework is that the organisation may

face the consequences for non-compliance with the

accountability principle of the GDPR. Such non-

compliance can result in an organisation facing fines

up to €20 million, or up to 4% of the annual

worldwide turnover of the preceding financial year,

whichever is greater. Hence the accountability

principle is a double-edged sword, with one side

containing the reputational trust and confidence

gained from acting in an accountable manner when

organisations are meeting its obligations versus

compliance failures resulting in reputational damages

and financial sanctions.

3 BEST PRACTICE FOR THE

DEMONSTRATION OF GDPR

ACCOUNTABILITY

We conducted a review of the literature to establish

best practice for the demonstration of regulatory

compliance. The review yielded very little direct

research of GDPR compliance; however, we

identified a body of relevant research in the area of

RegTech. The catalyst for the emergence of this

approach to regulatory compliance was the Global

Financial Crisis of 2007. The introduction of many

financial regulations, increasing operational costs and

significant regulatory fines, created significant

challenges for the Financial Industry. The response of

the industry was RegTech to meet the increasing

compliance challenges they faced (Butler, 2019). We

identified the four critical features of RegTech

systems to enable organisations successfully

demonstrate compliance with regulations. These are,

the enabling of a well-defined data governance

capability, applying ICT advances to regulatory

compliance, the agreement on common standards/

agreed semantics to enable the interoperability of

systems, and the role of regulators as facilitators for

the automation of regulation (Ryan, 2021). We will

discuss these in detail in the next sub-section.

3.1 Enabling a Well-defined Data

Governance Capability

Organisations need a dedicated data governance

capability to build common ground between the legal

and data management domains, to facilitate the digital

transformation of organisations and to enable

effective control and monitoring of data processing

for compliance purposes. Despite embracing the

productivity and agility gains of digitisation, many

organisations struggle with the basic principles of

data governance (Butler,2019). Organisations need to

have clearly defined data principles and treat data as

an asset. (Khatri, 2010). The agreed uses of that data

must be clearly defined, and the organisation must

ensure that the use of data relates positively to the

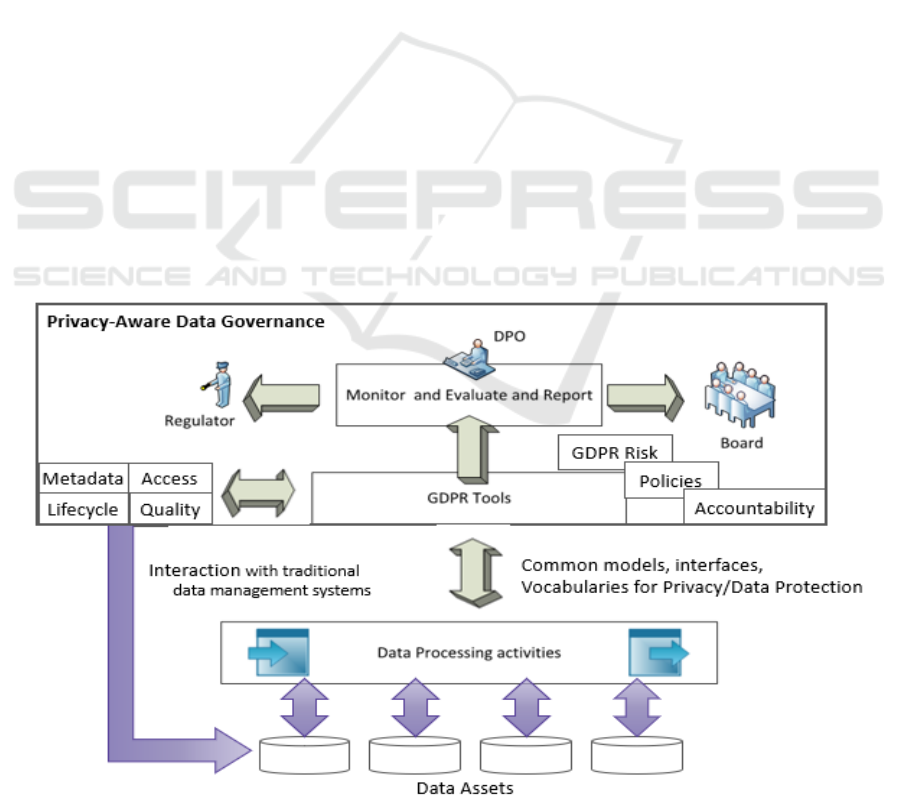

Figure 1: Privacy-Aware Data Governance to Support GDPR RegTech.

Demonstrating GDPR Accountability with CSM-ROPA: Extensions to the Data Privacy Vocabulary

593

regulatory environment. They need to set out as to

what are the organisational behaviours for data

quality, who will access the data, how data is

interpreted and what is the data retention period. The

application of structured data governance to

organisational data, coupled with agreed semantics,

can enable the smooth and efficient flow of data

between parties, thus bringing efficiencies to the

organisation (see figure 1). The challenge that

organisations are facing regarding personal data is

locating, classifying and cataloguing this data, i.e.

creation of appropriate metadata to enable

management of the personal data, and then deploying

a policy monitoring and enforcement infrastructure

leveraging that metadata to assure legal data

processing and generate appropriate compliance

records.

3.2 Applying ICT Advances to GDPR

Compliance

The adaption of new technologies has been at the

forefront of the successes of RegTech. A GDPR

RegTech solution will require the same approach to

new technology to facilitate efficient and effective

compliance. The Fintech revolution (Arner, 2015)

brought about the implementation of Big Data

collection and analytics techniques, machine

learning, Natural Language Processing (NLP),

Artificial Intelligence (AI), cloud technology,

DevOps (continuous development), Distributed

Ledger tech, software integration tools and many

other technologies in the financial industry. The cost

of compliance and the need for agile solutions

brought about the speedy and effective

implementation of such new technologies. A

RegTech approach to GDPR would require

organisations to implement such technologies in a

GDPR environment. The transformative nature of

technology (Arner, 2016) enjoyed by RegTech is

achievable in the GDPR environment through a new

approach to technology at the nexus of data and

regulation.

3.3 Agreement on Common

Standards/Agreed Semantics for

Personal Data Processing

The third requirement for GDPR RegTech is the need

to make personal data interoperable between systems.

Whilst the digital transformation of financial data in

RegTech has facilitated the application of technology

to this data; this may be more challenging in a GDPR

environment. The semantic modelling of GDPR

business processes would be a great benefit to an

organisation and provide for machine-readable and

interoperable representations of information allowing

queries to be run and verified based on open standards

such as RDF, OWL, SPARQL, and SHACL (Pandit,

2020). The combination of legal knowledge bases

with these models become beneficial for compliance

evaluation and monitoring, which can help to

harmonise and facilitate a joint approach between

legal departments and other stakeholders to the

identification of feasible and compliant solutions

around data protection and privacy regulations

(Labadie, 2019). There has been progress in

developing "Core Vocabularies', maintained by the

Semantic Interoperability Community (SEMIC), that

provides a simplified, reusable and extensible data

model for capturing fundamental characteristics of an

entity in a non-domain specific context (Pandit, 2020)

in this area to foster interoperability. This work

continues to be built on through the development of

the W3C Data Privacy Vocabulary (DPV) and the

PROV-O Ontology (Pandit, 2020).

3.4 Data Protection Supervisory

Authorities as an Enabler

The fourth requirement for GDPR RegTech is the

need for proactivity by regulators, who will work with

organisations to automate regulation and make

compliance easier to achieve. GDPR Regulators have

lacked the proactivity of financial regulators in the

facilitation of automated digital compliance. This

lack of leadership has resulted in organisations facing

the "pitfalls of a fragmented Tower of Babel

approach" (Butler,2019). The role of the supervisory

authority is a critical enabler and facilitator, for

RegTech. However, GDPR Regulators have been

relatively slow to take a similar role in comparison to

financial regulators. Our analysis of RegTech (Ryan,

2020a) (Butler,2019) has shown that compliance

monitoring and reporting to improve compliance

monitoring is achievable using technology when

flexible, agile, cost-effective, extensible and

informative tools are combined. When regulators

enable and facilitate digital compliance, and actively

promote digital regulatory compliance standards, and

act as facilitators for the automation of regulation,

they create an environment for digital compliance.

For GDPR RegTech to be successful GDPR

regulators, need to move towards a symbiotic

relationship with technology innovators and

organisations processing personal data to develop

open-source compliance tools, digital regulations,

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

594

sandboxes (Arner,2017) and tech sprints

(Arner,2017). This relationship would significantly

accelerate the successes of GDPR RegTech solutions.

4 CURRENT CHALLENGES TO

ROPA COMPLIANCE

A study conducted mid-2019 among more than 1100

executives across ten countries, and eight sectors

reported that only 28% of the responding

organisations were compliant with the GDPR at that

time (Cap Gemini, 2020). This low level of GDPR

compliance is a significant risk for organisations, so

why are they failing to be compliant? Jakobi et al.

describe the three approaches that organisations are

taking for dealing with the GDPR in day-to-day

business (Jakobi,2020). These strategies stretch from

"burying the head in the sand" to compliance to the

minimum level against a "first-time fine", to the few

organisations that see compliance as a quality feature

for their business customers or end-users and seek to

generate competitive advantage from GDPR

compliance.

The GDPR requires an organisation explicitly to

build and implement comprehensive internal data

privacy and governance programs (including policies

and procedures) that implement and operationalise

data privacy protections. Many Data Protection

Authorities agree that in order to have a good

overview of what is going on in an organisation, the

Register of Processing Activities is a vital element

(Nymity, 2018). Aside from being a legal obligation

on organisations, the record is an internal control tool

and, is a way to demonstrate an organisation's

compliance with GDPR

3

. It is a comprehensive record

of the personal data processing activities of an

organisation. It is integral to meeting the principle of

accountability as set out in Article 30 of the GDPR. It

not only provides an overview of the ongoing data

processing operations but also helps organisations to

decide which are the appropriate technical and

organisational measures that need implementation.

Furthermore, the ROPA supports the drafting and

updating of privacy notices, which will need to

include much information already included in the

register. Finally, the information included in the

ROPA allows assessing if processing activities are

"high risk" and thus need to be part of a Data

Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA).

Considering the importance of ROPA regarding

GDPR compliance, we analyse the approaches that

3

https://www.cnil.fr/en/record-processing-activities

organisations are taking to the creation and ongoing

maintenance of ROPAs. Several data protection

supervisory authorities have provided ROPA

templates to assist organisations to complete their

ROPA. These documents are spreadsheet-based

templates which can vary significantly between

regulators (Ryan,2020). These solutions are mainly

spreadsheet-based, they rely on qualitative input of

users, and they lack input or output interoperability

with other solutions.

The United Kingdom Data Protection Regulator

(ICO) recommends that organisations start by doing

an information audit or data-mapping exercise to

clarify what personal data the organisation holds and

where they hold it. The process requires a cross-

organisation approach to ensure that the organisation

is fully engaged in the process. This approach ensures

that that the organisation is not missing anything

when mapping the data processed by the organisation

The ICO adds that "It is equally important to obtain

senior management buy-in so that your

documentation exercise is supported and well

resourced."

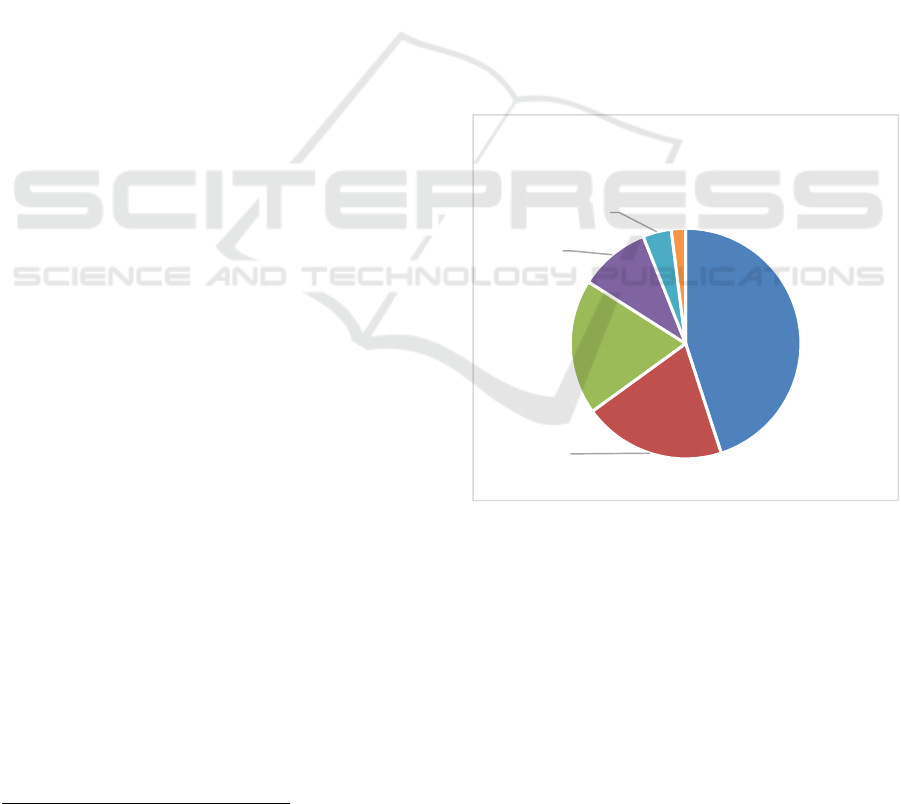

Figure 2: Primary Tool Used by Organisations for Data

Inventory and Mapping.

In practice, we find that almost half (45%) of

organisations complete their data mapping and

inventory operations using manual/informal tools,

such as email, spreadsheets, and in-person

communication (Figure 2). A further 10% of

organisations are using off the shelf vendor-supplied

software (IAPP/Trust Arc, 2019).

There has been significant investment by

organisations in privacy software over the last

Manual/Informal ,

45%

Customised

Software , 20%

Internally-

developed

system ,

19%

Vendor

Privacy

Software,

10%

Outsourced , 4%

Don't

Know , 2%

Primary Tool Used to Perform Data

Inventory and Mapping

Demonstrating GDPR Accountability with CSM-ROPA: Extensions to the Data Privacy Vocabulary

595

number of years. Whilst there are a variety of privacy

software solutions offered by vendors, "there is no

single vendor that will automatically make an

organisation GDPR compliant" (IAPP,2020). One

hundred forty-two vendors supply data mapping, data

inventory and ROPA software (IAPP,2020). The key

challenges with vendor supplied ROPA software are

as follows:

• they are stand-alone and lack interoperability

• they focus on manual or semi-automated

approaches that are labour intensive, rely on

domain experts

• these software solutions have been completed

enterprise without the input of the regulator.

• they lack standards-based approaches to

compliance

A recent survey of the ROPA practices of 30

public bodies found that only 7 (23%) of the

organisations met the threshold of having ROPA's

that were "sufficiently detailed for purpose"

(Castlebridge,2020). Among the failing identified in

this report are:

• Many ROPAs appear to generalised and vague

• Failing to integrate maintenance into the day to

day operations, resulting in ROPA not being kept

up to date

• Defaulting ownership to the Data Protection

Officer (DPO)

• Recording an inventory of records, not of

processing activities

• Insufficient details for technical and

organisational security measures

• Inaccurate or no retention periods declared

• Inconsistent approaches to ROPA maintenance

• Fragmentation of ROPAs across sub-divisions

leading to inconsistency.

Organisations are very much putting their head in

the sand regarding ROPA compliance. They are

failing to clearly, consistently and comprehensively

document their processing activities ROPA. They are

devolving responsibility to the DPO when it is the

organisation that is responsible for the demonstration

of compliance and not the DPO. They are exposing

themselves to significant risk in this area. They need

to adopt best practice for ROPA regulatory

compliance.

5 REQUIREMENTS FOR A

MACHINE-READABLE ROPA

In section 3, we identify the best practice for

supporting the demonstration of regulatory

compliance. In section 4, we show that organisations

are facing significant compliance challenges with

ROPA compliance (Castlebridge,2020).

Organisations continue to create and maintain

ROPAs through informal tools and spreadsheets

(IAPP-Trust Arc 2019). They need to go beyond a

paper-based strategy for compliance verification and

reap the benefits of ICT-based automation and move

to machine-readable ROPA accountability

compliance systems to support ROPA compliance.

These systems will require organisations to employ

systems with the following capabilities:

• Record accountability data

• Interoperable with platforms and tools

• Facilitate the digital exchange of data

• Standards-based

• Apply ICT advances to facilitate automation

• Industry agnostic

• Agile and flexible for expansion

In practice, this will require an organisation to

have an active data governance strategy and deployed

data governance tools or platforms. The organisation

needs to know what data they are holding, why they

are collecting it and what they do with it. This

knowledge must be captured in a machine-readable

format and be easily maintained and exchanged.

Organisations are facing significant difficulties when

implementing GDPR best practice due to a lack of

common ground between the legal and data

management domains (Labadie, 2019). Legal

professionals have led the data protection context

with limited insight into native digital methods to

define, enforce and track privacy-centric data

processing, for example only 3% of data subject

access requests are automated, and 57% are entirely

manual (IAPP 2020). This approach has resulted in

ad hoc or semi-automated organisational processes

and tools for data protection that are not fit for

purpose and block innovation and organisational

change (Ryan 2021).

The organisation needs to employ standard

models that can facilitate the digital exchange of

information between stakeholders. The need for

organisations and regulators alike to work together to

agree on common standards and agreed semantics for

personal data processing has never been greater.

There has been significant investment in governance

and privacy software to date by organisations (IAPP-

EY,2019). The investment would be best directed to

the development of platforms and tools using

interoperable protocols, APIs and data formats, like

RDF-based vocabularies. This investment would

support the creation of privacy-aware, accountability-

centric data processing ecosystems based on

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

596

toolchains, open standards, automated metadata

creation, ingestion and maintenance. These platforms

and tools can use the same standards to connect with

regulators, certification bodies and third parties to

verify compliance, build trust and automate

accountability. The role of supervisory authority has

been a major driving force in the success of RegTech;

however, Data Protection regulators are lagging their

financial counterparts (Ryan et al., 2021). There has

been some effort by data protection regulators to

provide templates self-assessment checklists and

guidance documents to make the business of

compliance easier through the guidance documents,

and templates, however this remains far removed

from the success of RegTech. Whilst each GDPR

regulator must apply the GDPR consistently (GDPR

recital 135), there have been very little in the form of

a unified approach to technical solutions to facilitate

GDPR ROPA compliance.

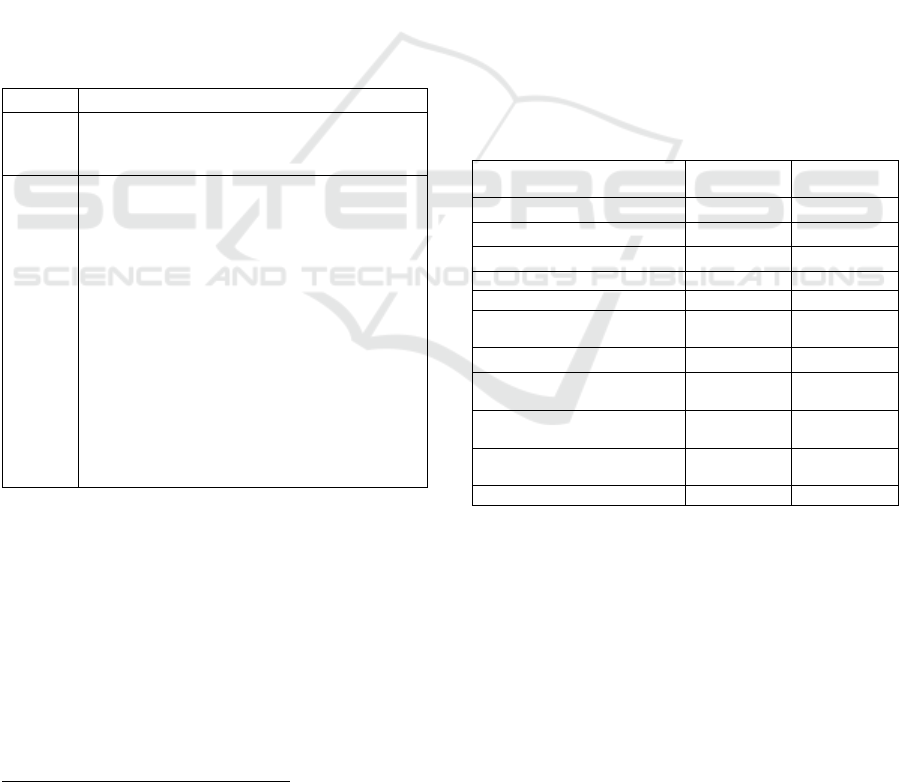

Table 1: Samples of Expectations taken from ICO

Accountability Framework.

Section

Ways to meet ICO expectations

6.2.1 You record processing activities in electronic

form so you can add, remove or amend

information easily.

6.3.1 The ROPA includes (as a minimum):

•Your organisation's name and contact

details, whether it is a controller or a

processor (and where applicable, the joint

controller, their representative and the DPO);

•the purposes of the processing;

•a description of the categories of individuals

and personal data;

•the categories of recipients of personal data;

•details of transfers to third countries,

including a record of the transfer mechanism

safeguards in place;

•retention schedules; and

•a description of the technical and

organisational security measures in place.

There have been progressive initiatives by some

regulators such as the UK regulator (ICO) who

published their accountability framework

4

in 2020.

The ICO describes the framework as an opportunity

for organisations large or small to meet their GDPR

accountability obligations. The ICO accountability

framework contains ten categories. Each category

contains a set of expectations (of how an organisation

can demonstrate accountability), and each

expectation contains many detailed statements (see

table 1 and table 2). An organisation must evaluate

4

https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/accountability-

framework/

their level of compliance relative to each statement

based upon a four-level scale ranging from not

meeting/ partially/ fully meeting this expectation, or

not applicable.

The ICO Framework contains a specific section

for ROPA, which is particularly beneficial for the

organisations as this details the regulator's

expectation that an organisation must reach for ROPA

compliance.

What is interesting though about the ICO's

framework is that for the first time, a regulator has

provided a comprehensive oversight of accountability

looks like, and what they will be looking for when they

investigate organisations. As part of the accountability

framework, the ICO has provided a detailed

accountability tracker which has several uses for

organisations, such as to record, track and report on

compliance progress. It can check the organisations

existing practices against the ICO's expectations to

identify where they could improve existing practices

and to clearly understand how to demonstrate

compliance and to increase senior management

engagement and privacy awareness across an

organisation.

Table 2: Breakdown of ICO Accountability Framework.

Category No. of

Expectations

No of

Questions

Leadership and Oversight 6 33

Policies and procedures 4 17

Training and awareness 5 17

Individuals' rights 11 42

Transparency 7 31

Records of processing and the

lawful basis

10 33

Contracts and data sharing 9 31

Risks and Data Protection

Impact Assessments.

5 29

Records management and

security

12 63

Breach response and

monitoring

8 38

77 334

The provision of the accountability tracker is a

progressive step by a regulator as it is a description of

what GDPR accountability is. The critical challenge

for organisations is to evolve from the existing ROPA

compliance solutions where ROPA are created and

maintained through informal tools and spreadsheets

(IAPP-Trust Arc 2019). The current approach is

resulting in a lack of interoperability and a lack of

interoperability with stakeholders.

Demonstrating GDPR Accountability with CSM-ROPA: Extensions to the Data Privacy Vocabulary

597

6 CSM-ROPA OVERVIEW

In section 3, we identified best practice for the

demonstration of compliance. In section 4, we have

shown how organisations are struggling to maintain

ROPA's, which is a crucial element to demonstrate

their GDPR compliance. We show that they are

resorting to manual solutions for completion and that

they are failing to take cognisance of best practice. In

section 5, we identify the requirements for a machine-

readable ROPA for accountability compliance. The

development of CSM-ROPA is motivated to take

these best practices, and semantically express

regulator supplied ROPA's.

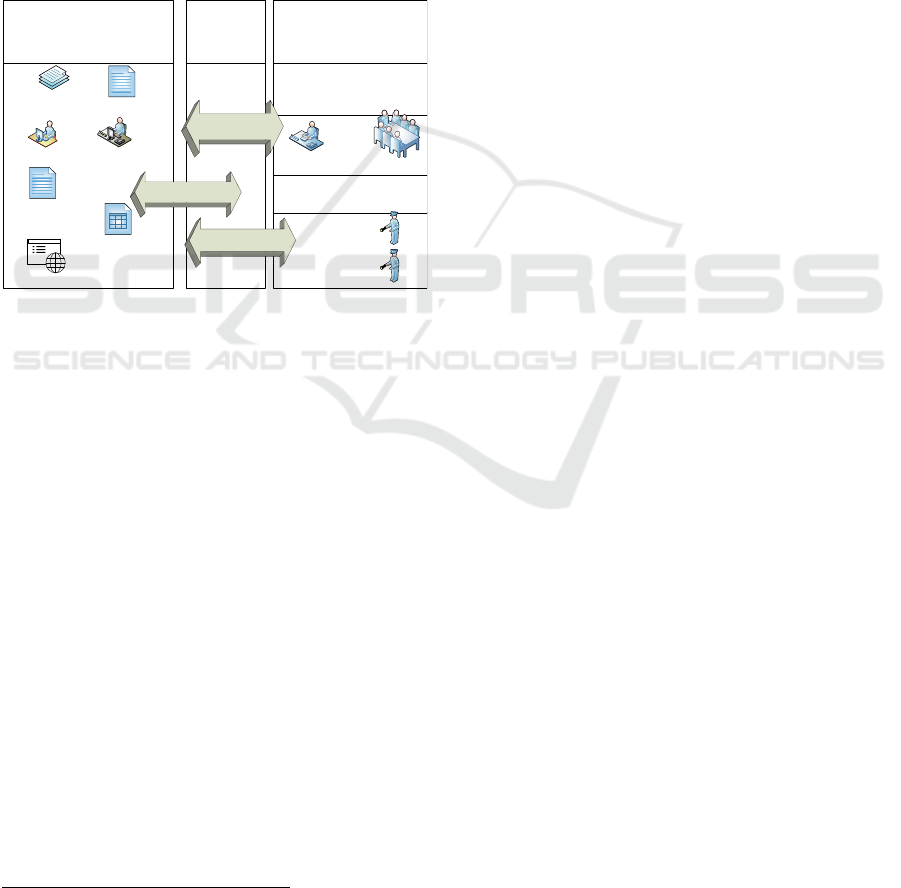

Board

DPO

Policies and

procedures

Technical and

Organisatonal

measures

Legal basis

Transparency

Transfer

Processors

GDPR Risk

Assessments

Certification

Bodies

Regulator

Business Processing

Activities

CSM-ROPA

Mediation

Layer

Reporting and

Monitoring Layer

External Accountability

Inspect and Certify

Internal Accountability

Monitor/Evaluate/ Report

CSM-ROPA

Compliance

Tools

Common models based

on DPV

Compliance Tools

Figure 3: CSM-ROPA as a Mediation Layer.

CSM-ROPA is a semantic model designed to model

six English language ROPA templates provided by

EU Data Protection Regulators and is a profile of the

data privacy vocabulary (DPV). A profile is "a named

set of constraints on one or more identified base

specifications, including the identification of any

implementing subclasses of datatypes, semantic

interpretations, vocabularies, options and parameters

of those base specifications necessary to accomplish

a particular function"

5

. The creation of the DPV

ontology follows guidelines and methodologies

deemed 'best practice' by the semantic web

community (Pandit, 2020). It follows a combination

of NeOn methodology (Suarez-Figueroa, 2012) and

UPON Lite methodology (DeNicola, 2016). The

methodology used for ontology engineering and

development lies on the reuse and possible

subsequent reengineering of knowledge resources, on

the collaborative and argumentative ontology

development, and the building of ontology networks.

CSM-ROPA will be deployed as a mediation

layer (see figure 3) between the business processing

5

https://www.w3.org/2017/dxwg/wiki/ProfileDescriptors

layer and the reporting and monitoring layer of the

organisation. In section 2 we detailed the obligations

that the organisation had to demonstrate compliance

to both internal stakeholders such as the board of the

organisation, and external stakeholders such as

individuals, business partners, shareholders and to

Data Protection Authorities. Organisations can be

complex entities, performing heterogeneous

processing on large volumes of diverse personal data,

potentially using outsourced partners or subsidiaries

in distributed geographical locations and jurisdiction

(Ryan,2021). We developed CSM-ROPA to act as a

mediation layer between such complex business

processing activities and the reporting monitoring

layer of the organisation. CSM-ROPA has evolved to

support machine to machine accountability

compliance verification. CSM-ROPA is the

application of RegTech best practice. CSM-ROPA is

a basis for the development of platforms and tools that

allow for the smooth interoperation of systems. The

use of CSM-ROPA for the creation and maintenance

of the organisations ROPA will enable automated

ROPA accountability compliance verification and

interoperability with regulators and certification

bodies alike. (Ryan, 2020b).

7 CASE STUDY

In this section, we examine the potential deployment

of our existing CSM-ROPA interoperable data

model. We select the ROPA section of the ICO

accountability tracker, where the regulator has set the

reporting requirements. We evaluate the extent that

an organisation can use CSM-ROPA as a mediation

layer to demonstrate ROPA compliance, and as a

basis for the development of compliance tools.

The ICO accountability tracker is an excel based

spreadsheet. The maintenance method for the

document is manual data entry by a user. The ICO

document is a static, stand-alone entity, and it does

not facilitate interoperability with any system, thus

significantly increasing the likelihood that it will not

be managed or maintained. This analysis will also

provide a use case for the DPV and help to identify

additional requirements for vocabulary, thus

providing valuable insight into the standard

requirements from industry and stakeholders to

identify areas where interoperability is a requirement

for the handling of personal data (Pandit, 2019).

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

598

7.1 Methodology

We evaluate to what extent that CSM-ROPA can

express ROPA compliance in its role as the mediation

layer between the business processing layer and the

reporting and monitoring layer of an organisation.

Our methodology for this case study involves the

following steps:

• Identify the ROPA category within the

Accountability Tracker for analysis

• Identify the unique terms stated in each

accountability expectation (see table 3)

• Compare the unique terms to CSM-ROPA terms

to establish if they were is a corresponding exact

pattern match of each other or a narrower match,

or no match (Scharffe,2009)

• For terms that have no match with CSM-ROPA,

evaluate if they exist in another known

vocabulary and use the additional vocabulary to

model the unique term

• For the remaining terms, make a

recommendation for inclusion in CSM-ROPA

7.2 Analysis

For this case study, we select the category "Records

of processing and lawful basis" for analysis, which

contains all relevant expectations for ROPA

compliance demonstration. The process we used to

analyse the category was that we identified 139

unique terms under "Records of processing and

lawful basis" category. We evaluated these terms to

establish if it was possible to map the terms using

existing terms in CSM-ROPA (see table 3 for

examples of outcomes).

Table 3: Sample of Mapping Outcomes.

Unique term taken

from Accountability

Tracker

The matching

concept found

in CSM-ROPA

Mapping/

proposed action

"The official

authority."

No match in

CSM-ROPA

Recommend

addition to

DPV

"An individual." Categories of

data subjects

Narrower

Match

"Contact details." Nil - use other

vocabularies

Use alternative

vocabulary

6

"Information required

for privacy notices."

Privacy notice Exact Match

"The purposes of

the processing."

Purposes of

processing

Exact Match

6

http://www.w3.org/TR/vcard-rdf/

7

http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-time/

8

http://www.w3.org/TR/vcard-rdf/

Our mapping (see Table 4) showed that CSM-

ROPA could express 41% of the unique terms

precisely, while another 51% could be expressed, as

a narrower match. CSM-ROPA did not have the

expressiveness to model 8% of the unique terms. This

equated to 11 terms. We have identified other

vocabulary's that could map 8 of these terms

78

, as they

are date/time and age-related terms.

Table 4: Summary of Mapping Results.

Outcome of Mapping No. of

terms

% of

terms

Exact mapping one to one 57 41%

Narrower mapping 71 51%

Mapped using other

vocabularies

8 6%

No mapping, add the term to

CSM- ROPA

3 2%

We have engaged with the Data Privacy Vocabula-

ries and Controls Community Group (DPVCG)

9

for

the addition of three additional terms that could not be

mapped for inclusion in the DPV and CSM_ROPA.

These terms are "Data Protection Regulator" "Data

Map "and "Legislation" (see RDF listing below). We

have shown that CSM-ROPA can map up to 92% of

them with additional vocabularies bringing the

mapping to 98%. The addition of three identified terms

to CSM-ROPA will enable the full mapping of the ICO

Accountability Tracker ROPA category.

Listing 1: New Terms for DPV in RDF format.

10

dpv:DataProtectionAuthority a

rdfs:Class ;

rdfs:label "Data Protection

Authority"@en ;

dct:description "Public body tasked

with data protection and privacy"@en.

dpv:DataFlowMap a rdfs:Class ;

rdfs:label "Data Flow Map"@en ;

dct:description "A data flow map to

support register of processing

activities"@en ;

rdfs:subClassOf

dpv:DataProcessingActivitySpecification

dpv: Legislation a rdfs:Class ;

rdfs:label "Legislation"@en ;

dct:description "A collective of

laws "@en .

9

https://www.w3.org/community/dpvcg/

10

https://github.com/Paul-Ryan76/ICO2CSM-ROPA

Demonstrating GDPR Accountability with CSM-ROPA: Extensions to the Data Privacy Vocabulary

599

8 CONCLUSIONS

Our research question asks, to what extent can CSM-

ROPA model the ROPA section of the ICO

Accountability Tracker to facilitate ROPA

compliance, and therefore assist organisations in

meeting the accountability principle of the GDPR?

Our case study identified that CSM-ROPA could

express 92% of the 139 identified unique terms

contained in this section of a regulator supplied

accountability tracker. When we consider other

vocabularies, it is possible to express another eight

terms bringing the mapping to 98%. We find that

CSM-ROPA did not contain the expressiveness to

model 3 terms. These terms are "Data Protection

Authority" "Data Flow Map "and "Legislation". We

have recommended these terms for inclusion in the

DPV. The contributions of this paper are that we have

demonstrated that the expressiveness required in a

semantic vocabulary to facilitate the demonstration of

ROPA compliance with the accountability principle

of the GDPR is achievable. We have identified

several vocabularies that can be linked to DPV to

improve expressivity. We have communicated

several terms to the DPVCG vocabulary for

inclusion. The outcome of this analysis is positive as

it indicates that with a small number of additions to

CSM-ROPA, it is possible to use a standardised

approach to the demonstration of ROPA compliance

using CSM-ROPA to meet the ROPA obligations as

set out by a regulator.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is partially supported by Uniphar PLC. and

the ADAPT Centre for Digital Content Technology

which is funded under the SFI Research Centres

Programme (Grant 13/RC/2106) and is co-funded

under the European Regional Development Fund.

REFERENCES

Arner, D., Barberis, J., Buckley, R., 2016 FinTech,

RegTech, and the Reconceptualisation of Financial

Regulation.

Arner, D. W., Zetzche, D.A., Buckley, R.F., Barberis, J.,

2017. Fintech and RegTech: Enabling Innovation while

Preserving Financial Stability, Georgetown Journal of

International Affairs. Vol. 18 47-58

Arner, D., Barberis, J., Buckley, R.., 2015. The Evolution

of Fintech: A New Post-Crisis Paradigm?

Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, 2010. Opinion

3/2010 on the principle of accountability.

Boven's, M., 2007. Analysing and Assessing

Accountability: A Conceptual Framework,

Butler, T., O'Brien, L., 2019 Understanding RegTech for

Digital Regulatory Compliance, Disrupting Finance,

Centre for Information Policy Leadership, 2017.

Certifications, Seals and Marks under the GDPR and

Their Roles as Accountability Tools and Cross-Border

Data Transfer Mechanisms.

Cap Gemini, 2019. https://www.capgemini.com/de-de/wp-

content/uploads/sites/5/2019/09/Report_GDPR_Cham

pioning_DataProtection_and_Privacy.pdf

Castlebridge Report (2020) https://castlebridge.ie/

research/2020/ropa-report/

Centre for Information Policy Leadership, 2018. The Case

for Accountability: How it Enables Effective Data

Protection and Trust in the Digital Society

De Nicola, A., Missikoff, M.: A lightweight methodology

for rapid ontology engineering. Commun. ACM 59(3),

79–86 (2016). http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2818359

IAPP-EY, 2019. Annual Privacy Governance (2019).

IAPP – Trust Arc, 2019. Measuring Privacy Operations.

IAPP, 2020 Privacy Tech Vendor Report (2020).

Jakobi, T., von Grafenstein, M., Legner, C. et al. 2020. The

Role of IS in the Conflicting Interests Regarding

GDPR. Bus Inf Syst Eng. 62, 261–272.

Khatri V., Brown C.V., 2010. Designing data governance.

Pg.148–152

Labadie, C., Legner, C., 2019. Understanding Data

Protection Regulations from a Data Management

Perspective: A Capability-Based Approach to EU-

GDPR.

Nymity, 2018. https://info.nymity.com/hubfs/GDPR%20

Resources/A-Practical-Guide-to-Demonstrating-

GDPR-Compliance.pdf

Pandit, H.J., 2020. Representing Activities associated with

Processing of Personal Data and Consent using

Semantic Web for GDPR Compliance.

Pandit, H.J., et al., 2019. Creating a Vocabulary for Data

Privacy: The First-Year Report of Data Privacy

Vocabularies and Controls Community Group

(DPVCG).

Ryan, P., Crane, M., Brennan, R., 2020. Design Challenges

for GDPR RegTech, ICEIS 92) 787-795.

Ryan, P., Crane, M., Brennan, R., 2021. GDPR Compliance

Tools – Best Practice from RegTech, LNBIP, to appear.

Ryan, P., Pandit H.J., Brennan, R., 2020. A Semantic

Model of the GDPR Register of Processing Activities.

Scharffe, F., 2009. Correspondence Patterns

Representation, Innsbruck

Suárez-Figueroa, M.C., et al., 2012. The NeOn

Methodology for Ontology Engineering, pp. 9–34.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

600