On the Efficacy of Online Proctoring using Proctorio

Laura Bergmans, Nacir Bouali, Marloes Luttikhuis and Arend Rensink

University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands

Keywords:

Online Proctoring, Proctorio, Online Assessment, Online Evaluation.

Abstract:

In this paper we report on the outcome of a controlled experiment using one of the widely available and used

online proctoring systems, Proctorio. The system uses an AI-based algorithm to automatically flag suspicious

behaviour, which can then be checked by a human agent. The experiment involved 30 students, 6 of which

were asked to cheat in various ways, while 5 others were asked to behave nervously but make the test honestly.

This took place in the context of a Computer Science programme, so the technical competence of the students

in using and abusing the system can be considered far above average.

The most important findings were that none of the cheating students were flagged by Proctorio, whereas only

one (out of 6) was caught out by an independent check by a human agent. The sensitivity of Proctorio, based

on this experience, should therefore be put at very close to zero. On the positive side, the students found

(on the whole) the system easy to set up and work with, and believed (in the majority) that the use of online

proctoring per se would act as a deterrent to cheating.

The use of online proctoring is therefore best compared to taking a placebo: it has some positive influence,

not because it works but because people believe that it works, or that it might work. In practice however,

before adopting this solution, policy makers would do well to balance the cost of deploying it (which can be

considerable) against the marginal benefits of this placebo effect.

1 INTRODUCTION

All over the world, schools and universities have had

to adapt their study programmes to be conducted

purely online, because of the conditions imposed by

the COVID-19 pandemic. The University of Twente

is no exception: from mid-March to the end of Au-

gust, no teaching-related activities (involving groups)

were allowed on-campus.

Where online teaching has worked at least reason-

ably well, in that we have by and by found effec-

tive ways to organise instruction, tutorials, labs and

projects using online means, the same cannot be said

for the testing part of the programme. Traditionally,

we test our students using a mix of group project work

and individual written tests. The latter range from

closed-book multiple choice tests to open-book tests

with quite wide-ranging, open questions. Such tests

are (traditionally) always taken in a controlled set-

ting, where the students are collected in a room for a

fixed period, at the start of which they are given their

question sheet and at the end of which they hand in

their answers. During that period, a certain number of

invigilators (in other institutions called proctors) are

present to observe the students’ behaviour so as to de-

ter them from cheating — defined as any attempt to

answer the questions through other means than those

intended and proscribed by the teacher. This system

for testing is, we believe, widespread (if not ubiqui-

tous) in education.

Changing from such a controlled setting to online

testing obviously opens up many more opportunities

for cheating. It is hard to exaggerate the long-term

threat that this poses to our educational system: with-

out reliable testing, the level of our students cannot

be assessed and a university (or any other) diploma

essentially becomes worthless. We have to do more

than just have students make write the test online and

hope for the best.

Solutions may be sought in many different direc-

tions, ranging from changing the nature of the test al-

together (from a written test to some other form, such

as a take-home or oral test), to offering multiple or

randomised versions to different students, or apply-

ing plagiarism checks to the answers, or calling upon

the morality of the students and having them sign a

pledge of good faith; or any combination of the above.

All of these have their pros and cons. In this paper,

rather than comparing or combining these measures,

Bergmans, L., Bouali, N., Luttikhuis, M. and Rensink, A.

On the Efficacy of Online Proctoring using Proctorio.

DOI: 10.5220/0010399602790290

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021) - Volume 1, pages 279-290

ISBN: 978-989-758-502-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

279

we concentrate on one particular solution that has

found widespread adoption: that of online proctoring.

In particular, we describe an experiment in using one

of the three systems for online proctoring that have

been recommended in the quickscan (see (Quickscan

SURF, 2020)) by SURF, a “collaborative organisation

for ICT in Dutch education and research” of which all

public Dutch institutes of higher education are mem-

bers.

1

Approach. Online proctoring refers to the princi-

ple of remotely monitoring the actions of a student

while she is taking a test, with the idea of detecting

behaviour that suggests fraud. The monitoring con-

sists of using camera, microphone and typically some

degree of control over the computer of the student.

The detection can be done by a human being (the

proctor, also called invigilator in other parts of the

Anglosaxon world), or it can be done through some

AI-based algorithm — or a combination of both.

The question we set out to answer in this paper is:

how well does it work? In other words, is online proc-

toring a good way to detect actual cheating, without

accusing honest students — in more formal terms: is

it both sensitive and specific? How do students expe-

rience the use of proctoring?

In answering this question, we have limited our-

selves to a single proctoring system, Proctorio

2

,

which is one of the three SURF-approved systems of

(Quickscan SURF, 2020). The main reason for se-

lecting Proctorio is the usability of the system; it is

possible to use it on the majority of operating systems

by installing a Google Chrome extension and it can

be used for large groups of students. It features au-

tomatic detection of behaviour deemed suspicious in

a number of categories, ranging from hand and eye

movement to computer usage or sound. The teacher

can select the categories she wants to take into ac-

count, as well as the sensitivity level at which the

behaviour is flagged as suspicious, at any point dur-

ing the proceedings (before, during or after the test).

Proctorio outputs an annotated real-time recording for

each student, which can be separately checked by the

teacher so that the system’s suspicions can be con-

firmed or negated. The system is described in some

detail in Section 2.

Using Proctorio, we have conducted a controlled

randomized trial involving 30 students taking a test

specifically set for this experiment. The students were

volunteers and were hired for their efforts; their re-

sults on the test did not matter to the experiment in

any way. The subject of the test was a first-year course

1

See https://surf.nl

2

See https://proctorio.com/

that they had taken in the past, meaning that the na-

ture of the questions and the expected kind of answers

were familiar. Six out of the 30 students were asked to

cheat during the test, in ways to be devised by them-

selves, so as to fool the online proctor; the rest be-

haved honestly. Moreover, out of the 24 honest stu-

dents, five were asked to act nervously; in this way

we wanted to try and elicit false positives from the

system.

Besides Proctorio’s capabilities for automatic

analysis, we also conducted a human scan of the (an-

notated) videos, by staff unaware of the role of the stu-

dents (but aware of the initial findings of Proctorio).

We expected that humans would be better than the

AI-based algorithm in detecting certain behaviours as

cheating, but worse in maintaining a sufficient and

even level of attention during the tedious task of mon-

itoring.

Findings. Summarising, our main findings were:

• The automatic analysis of Proctorio detected none

of the cheating students; the human reviewers de-

tected 1 (out of 6). Thus, the percentage of false

negatives was very large, pointing to a very low

sensitivity of online proctoring.

• None of the honest students were flagged as sus-

picious by Proctorio, whereas one was suspected

by the human reviewer. Thus, the percentage of

false positives was zero for the automatic detec-

tion, and 4% for the human analysis, pointing to

a relatively high specificity achievable by online

proctoring (which, however, is quite useless in the

light of the disastrous sensitivity).

Furthermore, we gained valuable insights into the

conditions necessary to make online proctoring an ac-

ceptable measure in the opinion of the participating

students.

The outcome of the experiment is presented in more

detail in Section 3, and discussed in Section 4 (includ-

ing threats to validity). After discussing related work

(Section 5), in Section 6 we draw some conclusions.

2 EXPERIMENTAL SETUP

To prepare the experiment, we had to find and instruct

participants, choose the technical setup, and deter-

mine what kind of data we wanted to do gather be-

sides the results of Proctorio’s automatic fraud detec-

tion.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

280

Participant Selection. At the time we carried out

the experiment, the issue of online proctoring had al-

ready received quite a bit of attention nationally and

had been discussed among the Computer Science stu-

dents; even though the University of Twente had early

on decided not to rely on online proctoring, the atti-

tude of the student body was overwhelmingly nega-

tive. Thus, we took our experiment as an opportunity

to involve the students more constructively and to be

transparent in our investigation. Moreover, we wished

to remove confounding influences, such as the intrin-

sic motivation of students to score well on the test. In

this light, we made the following choices regarding

the selection of participants:

• We called for volunteer participants among all the

Bachelor Computer Science students, this being

the typical target group for online proctoring.

• Participants were paid as Teaching Assistants for

the time they spent in doing the test and providing

feedback.

• The proctored test was created especially for the

purpose of the experiment; though it mimicked a

real test that all students had already taken (possi-

bly a year or more earlier), it was not part of the

actual test schedule.

A one-hour digital information session was organized

where interested students were informed about the

set-up of the test, the Proctorio system and their pri-

vacy. Students had the opportunity to pose questions,

which turned out to be mainly related to the storage

and use of their data by the Proctorio system and the

university. Students could volunteer to participate at

any point before, during or after this information ses-

sion.

In total, 30 students volunteered, out of a total

Bachelor population of 720; all of the volunteers were

admitted to participate in the experiment. The group

of participants was geographically diverse, reflective

of the actual population in the study programme: 46%

were international students, some of them physically

located outside the Netherlands at the time of the test.

The participants were divided into different popu-

lations:

• Cheating: A group of 6 students who attempted to

fool the system by cheating without detection. Af-

ter the information session, some of the students

themselves indicated their willingness to take up

this role. We invited these students and randomly

selected several others. As we needed a majority

group to compare with, we decided on selecting a

small sample of 6 to be cheating students.

• Nervous: A group of 5 students who were asked

to act nervous, by moving, looking around or mut-

tering more than they would normally do. (They

were not instructed in particular ways to act ner-

vous.) The underlying hypothesis was that such

behaviour could possibly generate false positives.

These students were randomly selected from the

participant list (after the cheaters had been cho-

sen) and were asked to confirm their willingness

to take up this role.

• Default: A control group of 19 students who took

the test as though this was a real exam, behaving

as they would under ordinary circumstances and

not trying to cheat.

The six cheating students were not given a specific

task. They did their own research and decided on

their course of action. They were informed of the

identities of the other cheaters, so that they could dis-

cuss their approach among themselves and stimulate

each other to come up with creative ideas. We did ask

the students to concentrate on digital/technical meth-

ods for cheating, as that would give us insight into

the technical sensitivity of the system. (This was also

based on an earlier, much smaller and more informal

test in which it became apparent that “classical”, non-

technical methods such as cheat sheets were virtually

undetectable by Proctorio.)

Technical Setup. In order to set up online proctor-

ing, we used Proctorio, integrated with the main ap-

plication for digital testing that is used at the univer-

sity: Remindo.

3

In order to take part, students had

to install a Google Chrome extension for Remindo

on their computer (which is available under all three

major OSs: Windows, Mac OS and Linux). Thanks

to the integration, students could activate Proctorio

when starting their exam in Remindo.

Remindo has different settings, in particular con-

cerning the use of any tools outside Chrome, or even

switching to any tabs outside the one in which Re-

mindo runs, for the duration of the test. For this ex-

periment, we used the strictest setting: the test was

presented in a web browser set to full screen, and no

other tabs or applications were allowed.

Before the students conducted the exam, they

were asked to do a system check. The goal of the

system check was twofold; it provided us insight in

technical difficulties students might encounter when

working with Proctorio and it was an opportunity for

the students to get to know the system already and

start well-prepared at the actual exam.

Proctorio produces its results in the form of a so-

called gradebook for each student. It uses a combi-

3

See https://www.utwente.nl/en/educational-systems/

about-the-applications/remindo

On the Efficacy of Online Proctoring using Proctorio

281

nation of audio, video and keystroke monitoring to

analyse the student’s behaviour. In doing so, it uses

so-called profiles that determine how suspicious cer-

tain types of behaviour are judged to be. To be pre-

cise, Proctorio distinguishes metrics and abnormali-

ties (measured based on the difference between the

behaviour of the individual student to the group aver-

age); a profile sets a weight for each of the metrics,

and an on/off switch for each of the abnormalities.

This results in a suspicion level ranging from 0–100

based on the weighted metrics and a count of flagged

abnormalities for each gradebook. Boundaries can be

set for judging the suspicion level to be low (by de-

fault up to 35), medium (by default between 36–59)

or high (by default 60 or higher).

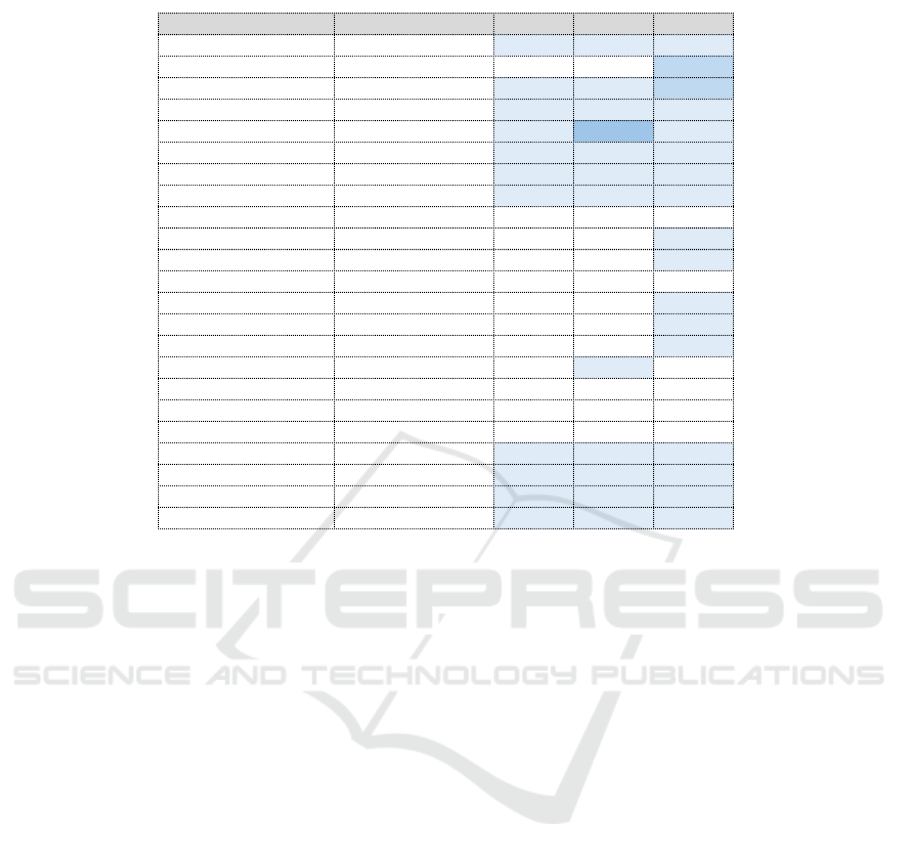

Proctorio has a default lenient profile. Besides

this, we defined a couple of more severe profiles,

which we called audio (weighing audio-related mea-

sures more heavily) and keystrokes (giving a higher

weight to keystrokes and copy/paste behaviours).

These, however, are not neutral; instead, we created

them specifically with the aim to catch out those stu-

dents which we knew to be cheaters, without also ac-

cusing those we know were honest (nervous or nor-

mal). In other words, we were trying to tune the sys-

tem to its best achievable sensitivity and specificity

based on the given gradebooks. Table 1 gives an

overview of the profiles.

Apart from checking the computed suspicion lev-

els and flagged abnormalities, one can also access the

gradebooks directly, and check in more detail what

happened, either as classified by Proctorio or through

own inspection of the recorded input.

2.1 Additional Data

Besides the analysis results provided by Proctorio, we

collected several other types of data.

First of all, the 30 gradebooks were reviewed by

six reviewers (each gradebook by a single reviewer),

all of whom were staff members. The reviewers did

not know which students had been assigned which

role. They noted which fraudulent actions they per-

ceived, and compared their findings against the stu-

dents’ own reports. In reviewing the gradebooks, the

reviewers were guided by what the system had in-

dicated as periods of abnormal activities — so their

findings were not completely independent of the au-

tomatic detection system. We will come back to this

in Section 3.

Next to the focus on the fraudulent actions, it was

also important to gain a more general view on the pro-

cess from a review perspective. Therefore, secondly,

the reviewers were asked to document their approach

and findings, to determine how human proctors can

be used best to complement the automatic detection

system.

Thirdly, the participants were asked to evaluate

their findings, in two ways: the cheaters were asked

to describe their approach, and all students filled in a

survey, asking them about

• ease of use,

• technical possibilities,

• privacy aspects, and

• advice to the teachers.

3 OUTCOME OF THE

EXPERIMENT

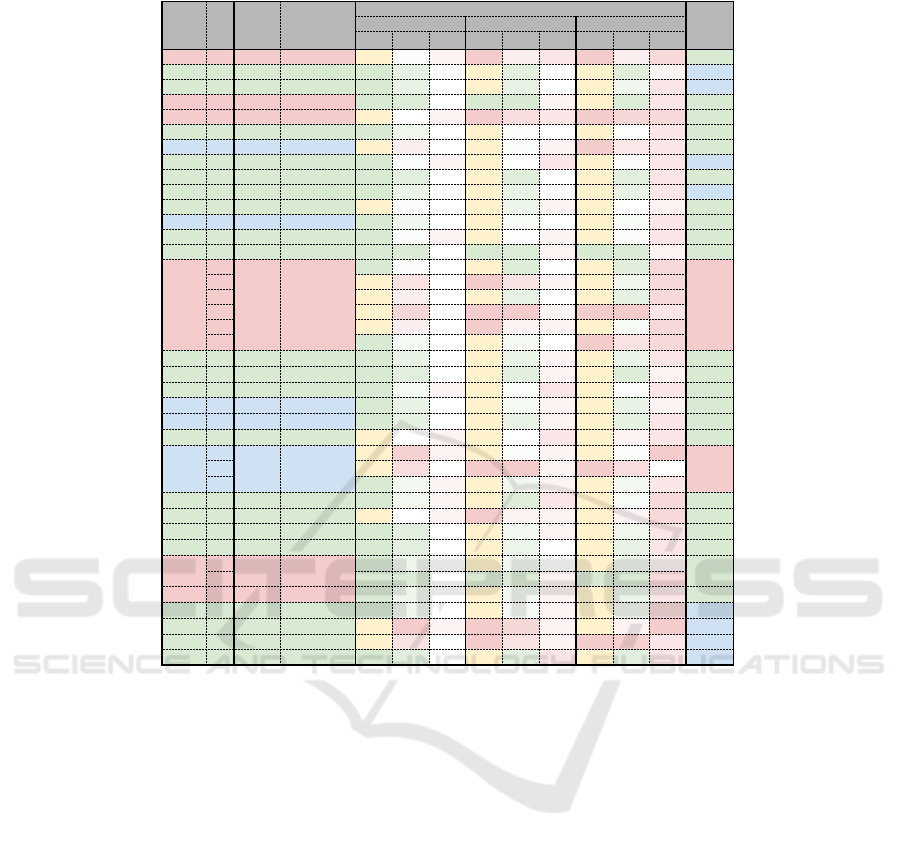

The overall results of the automatic detection (using

the three profiles) and the judgement of the reviewer

are shown in Table 2. Points to be noted are:

• Some students had to restart the test several times,

due to technical difficulties. The second column

(“#”) shows the separate attempts.

• The fourth column (“Cheat method”) summarises

the actions that the cheating students had under-

taken to circumvent the system. These are re-

ported in Table 3 in more detail.

• For each of the three Proctorio profiles we tried

out (see previous section), the table reports the

suspicion level, the rank (which is the place of the

suspicion level in the overall set of results) and

the flags (which is the number of abnormalities

noted). The colour coding of the level columns is

based on the default levels at which Proctorio con-

siders the performance to be unsuspicious (green,

35 or below), slightly suspicious (yellow, between

35 and 60) or suspicious (red, 60 or higher). The

rank columns are coloured red (for the top 20% of

suspicion levels) to green (for the bottom 80%).

• The final column (“Reviewer”) reports the find-

ings of the human reviewer. Reviewers did not

know which students were hackers and which had

been asked to act nervously. Videos with a sus-

picion level (in the default profile) of above 30%

were reviewed entirely. Between 21% and 30%,

reviewers clicked on all peaks that were indicated

in Proctorio’s gradebook. In videos with a risk

score of 20% or lower, only a spot check was per-

formed.

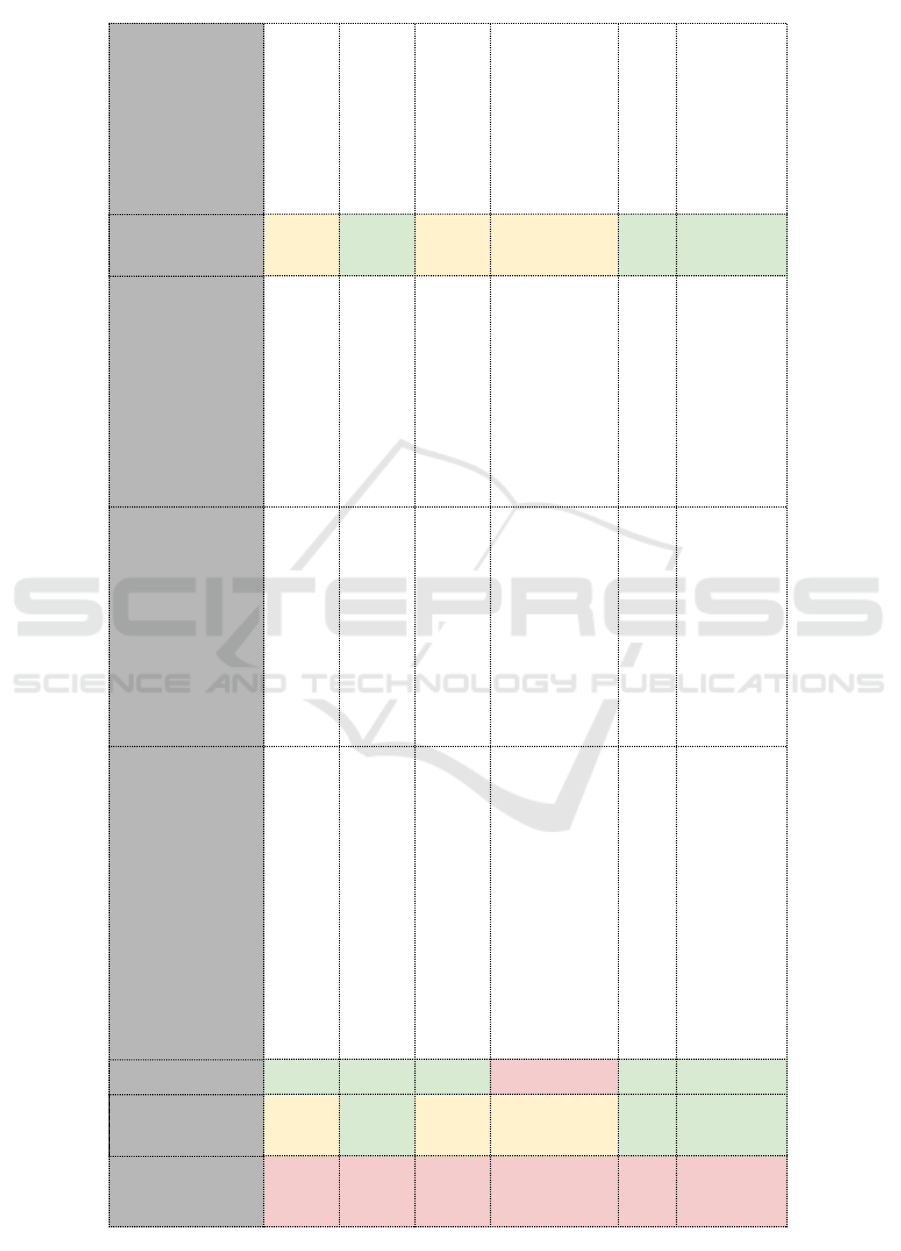

Table 3 shows in more detail what actions the cheaters

took, both successfully and unsuccessfully. As can

be seen, several students used virtual machines, none

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

282

Table 1: Proctorio profiles.

Category Option Default Audio Keystrokes

Frame metrics Navigating away 1 1 1

Kevstrokes 0 0 2

Copy/paste 1 1 2

Browser reisze 1 1 1

Audio levels 1 3 1

Head and eye movement 1 1 1

Multi-face 1 1 1

Leaving the room 1 1 1

Computer abnormalities Navigating away 0 0 0

Keystrokes 0 0 1

Copy/paste 0 0 1

Browser resize 0 0 0

Mouse movement 0 0 1

Scrolling 0 0 1

Clicking 0 0 1

Environmental abnormalities Audio levels 0 1 0

Head and eye movement 0 0 0

Leaving the room 0 0 0

Multi-face 0 0 0

Technical abnormalities Exam duration 1 1 1

Start times 1 1 1

End times 1 1 1

Exam collusion 1 1 1

of which were detected either by Proctorio or by the

reviewers. For the virtual machines, the screen res-

olution was odd, as the window was resized in order

to fit the virtual machines onto the student’s screen,

and this was flagged as an abnormality by Procto-

rio. However, many of the honest students were also

flagged for irregular screen resolution. The audio

level was also not flagged as abnormal by Proctorio,

even for those who did use audio calls (in combination

with a virtual machine) as their method of cheating.

To get a better idea of the usefulness of the Proc-

torio results, we refer to a recommendation from

Technical University Eindhoven, which states that the

top 20% of suspicion levels should always be man-

ually reviewed. This means that, in a regular work-

flow using online proctoring, any students not ranked

among the top 20% would certainly never be sus-

pected of cheating. In our experiment, only one stu-

dent (Test08) falls into that top 20% for the default

(lenient) profile; two more (Test02 and Test06) rise to

the top 20% under either the audio or the keystroke

profile. We then took a final step, namely to try and

create a dedicated Proctorio profile for each of the

cheaters, in order to catch them out. If this fails for

a given cheater, then we may conclude that the in-

put data that Proctorio collects is, under no circum-

stances, sufficient to expose this student. (Of course,

if a dedicated profile does show up a given cheater,

that does not actually mean that it is a useful profile

in general, as it was created based on prior knowledge

about who was actually cheating.)

The results are shown in the last three columns of

Table 3. Three out of six cheating students turn out to

be undetectable by any means whatsoever. We also

wish to recall that, even though Test02 and Test06

are in the top 20% under some profiles, this does not

equal detection, as in both cases our human reviewer

cleared the student, as reported in Table 2.

3.1 Reviewer Evaluation

The reviewers discussed the process and findings.

The most important findings were:

• You can’t see what students are doing from the

chest down because of the way laptop cameras are

aimed. If students were subtle they could use a

phone / notes undetected.

• The room scan is not a very useful feature. Stu-

dents either moved the camera too quickly and

made a blurry recording, or they failed to record

their desktop.

• Watching an entire recording is very boring, mak-

ing it very hard to concentrate for long. Everyone

changed to clicking highlights in the incident re-

port instead.

• The ID scanner does not always yield a clear pic-

ture. Sometimes we could not recognize the stu-

dent.

On the Efficacy of Online Proctoring using Proctorio

283

Table 2: Proctorio and reviewer results.

ID # Role Cheat method

Proctorio

Reviewer

Default profile Audio profile Keystroke profile

Level Rank Flags Level Rank Flags Level Rank Flags

Test02 1 Cheater Audio call 36 13

1

62 7

2

60 7

3

Default

Test03 1 Default 21 31

0

41 34

0

41 36

1

Nervous

Test04 1 Default 22 28

0

43 29

0

50 22

2

Nervous

Test05 1 Cheater Virtual desktop 13 38

0

15 40

1

37 38

2

Default

Test06 1 Cheater Virtual desktop 37 10

1

66 4

2

64 3

3

Default

Test07 1 Default 25 23

0

54 13

0

56 12

2

Default

Test08 1 Nervous 39 7

0

53 14

1

61 6

2

Default

Test10 1 Default 35 15

1

57 11

2

55 13

2

Nervous

Test11 1 Default 20 33

0

40 35

0

44 33

2

Default

Test12 1 Default 23 27

0

44 28

0

46 28

2

Nervous

Test13 1 Default 36 13

0

46 25

1

58 11

1

Default

Test14 1 Nervous 27 22

0

52 17

0

54 17

2

Default

Test15 1 Default 35 15

1

55 12

1

55 13

2

Default

Test17 1 Default 12 39

0

34 38

1

34 39

1

Default

Test18

1

Cheater Audio call

35 15

0

37 37

0

43 35

3

Cheater

2 41 5

0

63 5

1

49 23

3

3 39 7

0

43 29

0

45 31

3

4 48 3

0

70 1

1

70 1

2

5 39 7

0

60 8

1

54 17

3

6 34 18

0

48 19

0

62 5

3

Test19 1 Default 22 28

0

45 27

1

47 26

2

Default

Test20 1 Default 20 33

0

42 32

1

38 37

1

Default

Test21 1 Default 33 19

1

53 14

2

55 13

2

Default

Test22 1 Nervous 22 28

0

48 19

1

46 28

1

Default

Test23 1 Nervous 21 31

0

43 29

1

45 31

2

Default

Test25 1 Default 37 10

1

59 10

2

59 8

2

Default

Test27

1

Nervous

49 2

1

53 14

1

55 13

4

Cheater2 45 4

0

70 1

1

63 4

0

3 32 20

1

47 21

1

53 20

2

Test29 1 Default 30 21

1

38 36

2

54 17

3

Default

Test30 1 Default 37 10

1

60 8

1

59 8

3

Default

Test31 1 Default 20 33

0

47 21

1

49 23

2

Default

Test32 1 Default 20 33

0

46 25

0

46 28

2

Default

Test33

1

Cheater Whatsapp

25 23

0

47 21

0

49 23

1

Default

2 12 39

0

24 39

1

18 40

3

Test34 1 Cheater Virtual desktop 25 23

0

47 21

1

47 26

2

Default

Test35 1 Default 25 23

0

49 18

1

51 21

3

Nervous

Test36 1 Default 51 1

1

69 3

1

59 8

4

Nervous

Test36 2 Default 41 5

0

63 5

1

65 2

2

Nervous

Test36 3 Default 20 33

0

42 32

2

44 33

2

Nervous

• Some students had a lot of sound flags due to out-

side noise. Others were flagged a lot for looking

away because they were restless or working on an

exam question on paper (on their desk).

3.2 Student Evaluation

As described in Section 2, the participating students

were asked to provide us with their evaluation. All the

participating 30 students filled out the digital evalua-

tion survey. The survey consisted of 17 questions (5

open and 12 closed questions). The highlights are pre-

sented below; Figure 1 presents some of the collected

answers in the form of a bar chart.

Ease of Use. In general students are positive about

the user-friendliness of the Proctorio system. Four

students had to contact the Proctorio help desk before

they could start the exam. The issues were resolved

and all of the students (30) were able to conduct the

exam. The majority of students state that it is easy

to start the exam combination Remindo-Proctorio and

that the integration between these systems works well.

About 75% of students state that Proctorio is a suit-

able option for remote assessment.

Technical Possibilities. All students were able to

start the exam. Some students mentioned that they

had technical issues during the exam where most of

them were related to getting started with the exam,

for example microphones and webcams that were not

functioning.

Privacy Aspects. Initially students were quite con-

cerned about their privacy especially when it comes to

the storage of their data and how the data is handled

after the exam process. Students have the following

concerns when it comes to privacy:

• Concerns about the distribution of the recording

to third parties

• Having to install an extension in the browser

• Having to scan my room

• How long will the data be stored and who has ac-

cess to the data

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

284

Table 3: Actions undertaken by cheaters.

ID

Proctorio default

score (rank)

Caught by reviewer?

Cheat actions (successful) Cheat actions (unsuccessful) Dedicated Proctorio settings

Proctorio dedicated

score (rank)

Comments

Test02 36

(13th)

No Lowered volume on input mic, ran a Discord

call in the system tray and continued to talk

to people. Used a Bluetooth mouse that can

switch between devices.

Virtual machine attempted on

different operating systems, but

the virtualized camera never

passed the system check.

Raise frame metric 'Audio levels'

from 1 to 2; add environmental

abmormality 'Audio levels'

48

(4th)

Test05 13

(28th)

No Virtual box. Had websites and WhatsApp

open during the exam, and class notes.

Paused scrolling on the screen to minimize

abnormal scrolling behavior.

Tried to get webcam on a loop.

Tried to find Proctorio source code

No combination of settings was

found that could raise this

student into the top 20%

N/A Even with the strictest

settings, the abnormalities

do not go above 2

Test06 36

(10th)

No Virtual box, similar to Test05. Used the web

to look up answers.

Raise frame metric `Keystrokes'

from 0 to 1; add environmental

abnormalities 'Mouse movement'

and 'Clicking'

49

(7th)

Test18 48

(3rd)

Yes Opened Discord in another desktop on her

laptop so it was not visible in the taskbar.

Friend Googled questions visible on her

screen stream. Answers delivered over voice

chat. Was able to disable microphone after

initial check, so answers via voice chat were

not detected.

Was locked out of Proctorio

several times when attempting to

switch screens.

N/A Student was already in the

top 20% using the default

profile

Test33 25

(26th)

No Used paper notes. Took a picture with his

phone and sent to a friend. Researched

answers on his phone.

No combination of settings was

found that could raise this

student into the top 20%

N/A Head/eye movement was

not sufficiently different

from other students

Test34 25

(24th)

No Virtual desktop (Windows). Virtual keyboard

so typing would not be detected. Googled

answers during the exam. To get around

virtual webcam problem, changed the name

of virtual webcam occurrences in the registry,

after which it was no longer detected.

Virtual webcam initially detected. No combination of settings was

found that could raise this

student into the top 20%

N/A

On the Efficacy of Online Proctoring using Proctorio

285

Figure 1: Student evaluation.

Advice. As the student opinion is a very important

aspect of the acceptation of a Proctoring solution, we

asked the students what the University should defi-

nitely take into account when considering continua-

tion of proctoring. A summary of the given answers:

• Clearly communicate about the privacy aspects;

which data is stored where and visible by whom?

• There will always be students that try to outsmart

a system

• Prefer to have physical exams and only use proc-

toring when really needed, for the people that can-

not come to campus

• The room scan is not thorough enough and there-

fore makes it easy to work-around (cheat)

• Think about bathroom possibilities during the ex-

ams

• For some exams it could be difficult to only work

on one screen, which is an automated setting in

Proctorio.

4 ANALYSIS

The takeaways of the results presented above are as

follows:

1. Proctorio (in the combination with Remindo, as

used here) is an easy-to-use system for students

and teaching staff;

2. When properly informed, students are not op-

posed to the use of online proctoring, though other

testing methods are clearly preferred;

3. Proctorio cannot reliably (or in some cases not

at all) detect technical cheats that Bachelor Com-

puter Science students can come up with (in other

words, its sensitivity is unacceptably low);

4. In seeming contradiction with the above, students

are (in a clear majority) of the opinion that the use

of Proctorio will prevent cheating.

The “seeming contradiction” between the demon-

strated poor actual efficacy of online proctoring on

the one hand and its perceived benefit on the other

can at least partially be resolved by observing that the

former is about detection, whereas the latter is about

prevention. There are clearly some forms of cheating

which would be so easy to detect using online proctor-

ing — like sitting next to each other and openly col-

laborating — that they are automatically prevented,

and in fact were not even tried out by our group of

cheaters. In fact, such cheat methods would be de-

tectable by a technically far less involved system than

the one offered by Proctorio.

Granted that such “casual cheats” are prevented,

what remains are the “technical cheats” such as the

ones employed by our participants. We have shown

that those are virtually un-detectable through online

proctoring; so the question is if there is any preventive

effect. Any such effect will have to stem from the per-

ception of students that the chance of getting caught is

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

286

nevertheless non-zero. Since not all students are risk-

averse, some of them have great confidence in their

technical abilities, and some will even regard it as a

challenge to “beat the system”’, it follows that online

proctoring will not suffice to prevent technical cheats.

We therefore pose that the use of online proctoring as

the primary way to ensure reliability of online testing

is very dubious.

Internal Validity. As we have used an experimental

setup, there are certain threats to the internal validity

that we have had to take into account.

The first point is related to the student group that

participated in the experiment. As the students were

not graded for their effort, there was less at stake for

them than in a real test. This might affect their stress

level, especially for the group of cheaters, being lower

than at an actual test and hence making it harder to de-

tect cheats. On the other hand, the extrinsic incentive

of being paid made them take their role very seriously,

as is also visible in the Proctorio recordings.

Another issue related to the student group is the

representativeness of the sample. Besides the limited

number of participants (30), the selection process was

not structured: students could show their interest to

participate. This could lead to participants that have

a strong opinion about the proctoring, with increas-

ing motivation to successfully cheat. It is not know

how well the sentiment of the experimental group re-

flects the student population. During the informa-

tion session the importance of this experiment for the

decision making of the University was also stressed,

which might have influenced the students’ decision to

participate.

As we wanted to know with which kind of cheat-

ing methods students would come up with, we did not

give specific instructions to the cheaters. In conse-

quence, they mostly selected somewhat similar ap-

proaches. There might be other cheat methods that

were not tried out, to which our observations are

therefore not directly applicable. We did ask the par-

ticipants to focus on technical cheat methods because

from a prior, more superficial check it had already be-

come apparent that more traditional methods, such as

the use of cheat sheets, are hard to detect with proc-

toring software.

External Validity. Our experimental student group

consisted of only Computer Science students. These

are certain to be more technically proficient than the

average student, hence this might have implications

for the external validity. Next to their technical abili-

ties, Computer Science students also might find it mo-

tivating to enrich their knowledge about these kind of

new features and the possibilities to work around the

system.

Next to giving the cheating students the freedom

to select their own methods, we also informed them

about the other cheating students, so that they could

discuss their approach. In a real situation, it might be

less likely that potential cheaters seek each other out

— although anecdotally we have heard that students

have done exactly that in some cases, in connection

with real online tests.

A final threat to external validity is the fact that we

have conducted our experiment using a single tool,

Proctorio, and nevertheless have used the results to

draw conclusions about the general principle of on-

line proctoring. We believe that this is justified be-

cause Proctorio is representative of the cutting edge

in tooling of this kind; we feel that it is unlikely that

the shortcomings we have observed would be absent

in other tools.

System Limitations. One of the criteria during the

selection of Proctorio was that it should be possible

for the majority of students to work with the tool with-

out having any technical difficulties. The Proctorio

system fits this need because of its use as a Google

Chrome extension. the consequence of this approach

is that virtual machines are hard to detect because

there is less influence on the hardware of the student.

The students in our test quickly came to this conclu-

sion as well and all decided to follow more or less a

similar approach of working with a virtual desktop.

5 RELATED WORK

The worldwide shift towards online education in-

duced by Covid-19 brought the conversation on the

credibility of online assessment methods back to

light. When on-site testing is no longer an option,

an effective way to ensure students’ integrity during

exams is a necessity to maintain the value of degrees

that universities deliver around the world. The choice

of a suitable proctoring tool amongst the plethora of

products available is not trivial. Hussein et al. com-

pared online proctoring tools to decide which should

be adopted at the University of the South Pacific, out

of which the decision was to continue with Proctorio

(Hussein et al., 2020).

At the University of Twente, we ran two prior

experiments with candidate proctoring tools, the Re-

spondus Lockdown Browser and the MyLabsPlus en-

vironment, in 2016 and 2017 (Krak and Diesvelt,

2016; Krak and Diesvelt, 2017).Our findings con-

cluded that such tools did not preserve the validity

On the Efficacy of Online Proctoring using Proctorio

287

of digital exams, as both were proven to be vulner-

able and surpassable in a plethora of ways. We have

not found further research into the efficacy of such

methods, besides these prior experiments and the cur-

rent paper. Other online proctoring tools which record

the examinees during their test face criticism related

to privacy issues and raising anxiety levels for test

takers (Hylton et al., 2016). The privacy issues are

also among the concerns found in (Krak and Diesvelt,

2016; Krak and Diesvelt, 2017).

Regarding online proctoring, we look at two related

research lines, one that tackles the acceptance of these

systems by examinees, and another that looks at how

it impacts the performance in a given test.

In 2009, using Software Secure Remote Proctor-

ing SSRP system, researchers conducted an experi-

ment with 31 students from 6 different faculties in a

small regional university to evaluate students’ accep-

tance of online proctoring tools. The results showed

that slightly less than half the students expressed their

support for online proctoring tools, whilst a quarter of

the students expressed refusal of such proctoring tech-

niques (Bedford et al., 2009). Lilley et al. investigated

the acceptance of online proctoring with a group of 21

bachelor students from 7 different countries. Using

ProctorU, the subjects participated in an online for-

mative and two online summatve assessments. 9 of

the 21 participants shared their experiences with on-

line proctoring, 8 of which expressed their support to

use online proctors in further modules (Lilley et al.,

2016). A later experiment conducted by Milone et al.

in the university of Minnesota in 2017 concerned a

larger pool of students, 344, and showed that 89% of

the students were satisfied with their experience using

an online proctoring tool, ProctorU, for their online

exams, while 62% agreed that the setup of the proc-

toring tool takes less than 10 minutes (Milone et al.,

2017).

Another direction in proctoring research concerns

the impact of proctoring tools on test scores. A study

by Weiner and Hurtz contrasted on-site proctoring to

online proctoring. The experiment concerned more

than 14.000 participants and concluded that there is

a high overlap between the scores of the examinees

in both online and on-site settings. Furthermore, the

examinees dissociated their test scores from the type

of proctoring in place (Weiner and Hurtz, 2017). In a

different setting, Alessio et al. compared the scores of

students in proctored and unproctored settings. The

study concerned 147 students enrolled in a online

course on medical terminology. The experiment set-

ting allowed students to be divided over 9 sections,

according to their majors, 4 of which took an online-

proctored test, whilst the remaining 5 took an unproc-

tored test. The results of the study show that stu-

dents in the unproctored setting scored significantly

higher (14% more) than their proctored counterparts,

and spent twice as much time taking the tests, which

the investigators linked to unproctored tests allowing

much space for cheating (Alessio et al., 2017). A

similar result was achieved by Karim et al., whose

experiment setup involved 295 participants who were

handed out to cognitive ability test, one that is search-

able online and one that isn’t. The experiment saw

30% of the participants withdrawing from the proc-

tored test compared to 19% in the unproctored one,

it also confirms that unproctored examinees scored

higher than the proctored ones. Opposing (Alessio

et al., 2017), Hylton et al. administered an experiment

with two groups of participants, wherein the first takes

an unproctored exam while the other is proctored on-

line. Though the results show that the unproctored ex-

aminees score 3% more than their proctored peers and

spend 30% more time on the test, the researchers of-

fer a different interpretation linking the slightly lower

results in proctored settings to higher anxiety levels

(Hylton et al., 2016). Results from a study conducted

at the University of Minnesota show slightly differ-

ent results from (Alessio et al., 2017) and (Karim

et al., 2014). In this setup, students taking a psy-

chology minor afford the freedom of choosing on-

site or online proctored exams. The study spans three

semesters and found that the scores of online exam-

inees were 8% lower than their on-site counterparts

for two semesters; this difference disappeared in the

third semester with both types of examinees scoring

similar results (Brothen and Klimes-Dougan, 2015).

A more recent study by Neftali and Bic compared the

performance of students taking an online and an on-

site version of the same discrete math course. The

study found that while online students score higher in

online homework, their results in the online proctored

exams are 2% less from their online peers.

Dendir and Maxwell (Dendir and Maxwell, 2020)

report on a study ran in between 2014 and 2019,

in which the scores of students in two online

courses, principles of microeconomics and geography

of North America, were compared before and after

the adoption of a web-based proctoring tool in 2018,

Respondus Monitor. The experiment showed that af-

ter the adoption of online proctoring the scores have

dropped on average by 10 to 20%. This suggests, that

prior to the adoption of proctoring, cheating on online

exams was a common occurrence. This confirms that

the use of online proctoring has a preventive effect, as

was also suggested in our own student survey.

Vazquez et al. (Vazquez et al., 2021) ran a study

with 974 students enrolled in two sections —online

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

288

and physical on Winter 2016 and Spring 2017 respec-

tively— of a microeconomic principles course to in-

vestigate the effectiveness and impact of proctoring

on students’ scores. For the face-to-face course, three

exams were scheduled. The experiment showed that

the unproctored students scored 11.1% higher than

the students who took the exam with a live proctor in

the first exam. The gap grew in favor of the unproc-

tored students to 11.2% higher on the second exam,

to reach 15.3% on the third. These differences how-

ever were smaller for online students who were proc-

tored with a web-based proctor (ProctorU) in two ex-

ams. Unproctored students scored 5% higher in the

first exam, and 0.8% higher on the second. Vazquez

el al. tied the larger gap in proctored physical exams

to students collaboration during exams.

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

Most teachers and managers involved in the pro-

cess of testing and the decisions on how to conduct

it online have a very good grasp of the difficulties

involved. For instance, the whitepaper (Whitepa-

per SURF, 2020) by SURF (the same organisation

that performed the quickscan on privacy aspects in

(Quickscan SURF, 2020)) gives a rather thorough

analysis of risk levels and countermeasures to cheat-

ing. Online proctoring is merely one and not the most

favoured of those countermeasures. This is also con-

firmed by students. It is therefore quite important to

involve them as stakeholders when choosing to intro-

duce proctoring as a preventive measure.

With this paper, we have aimed to inject some data

into the discussion, of a kind that is not widely found

nor easy to obtain, namely regarding the sensitivity

of online proctoring — in other words, its ability to

avoid false negatives. Without carrying out a con-

trolled experiment, as we did, it is not really possible

to say anything about this with confidence.

On the other hand, the used experimental approach

also implies limitations (already discussed in Sec-

tion 4) and suggestions for future work. Further re-

search in real exam settings will provide more insight

into the effectiveness of online proctoring. The vol-

untary, mono-disciplinary and relatively small size of

the sample that was used in this experiment also sug-

gests that future work is needed. Conducting research

on a bigger student population, coming from differ-

ent disciplines, would give a more complete overview

on the possibilities for the implementation of online

proctoring. A final proposition for future work is on

the use of different software systems and different

ways of online proctoring. The selection of the Proc-

torio software implied certain design decisions dur-

ing the process. Future work could provide a more

in depth overview of different software systems, but

also different methods of online proctoring, e.g. live

proctoring and automated proctoring. The effective-

ness and student experience should be compared and

evaluated.

For the purpose of the decision process of our univer-

sity, the results of this experiment were written up in

(Bergmans and Luttikhuis, 2020), which also contains

some more details on the behaviour of the (pseudon-

omyzed) individual students. At the moment of writ-

ing, this is used in a University-wide discussion on

the adoption of online proctoring (using Proctorio).

An unavoidable component of any such discussion

is: what are the alternatives? If we do not impose au-

tomatic online proctoring, using Proctorio or one of

its competitors, do we take the other extreme and just

trust on the students’ good behaviour, possibly aug-

mented by oral check-ups of a selection of students?

This is not the core topic of this paper, and merits a

much longer discussion, but let us at least suggest one

alternative that may be worth considering: live online

proctoring, with a human invigilator watching over a

limited group of students, and no recording. We hy-

pothesise that this will have the same preventive effect

discussed in Section 4: casual cheats can be detected

easily, and technical cheats cannot.

REFERENCES

Alessio, H., Malay, N. J., Maurer, K., Bailer, A. J., and

Rubin, B. (2017). Examining the effect of proctoring

on online test scores. Online Learning, 21(1).

Bedford, W., Gregg, J. R., and Clinton, S. (2009). Imple-

menting technology to prevent online cheating: A case

study at a small southern regional university (SSRU).

MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching,

5(2).

Bergmans, L. and Luttikhuis, M. (2020). Proctorio test re-

sults and TELT recommendation. Policy document,

Technology Enhanced Learning & Teaching, Univer-

sity of Twente. Availablehere.

Brothen, T. and Klimes-Dougan, B. (2015). Delivering on-

line exams through ProctorU. Poster at the Minnesota

eLearning Summit; online version here.

Dendir, S. and Maxwell, R. S. (2020). Cheating in online

courses: Evidence from online proctoring. Computers

in Human Behavior Reports, 2.

Hussein, M., Yusuf, J., Deb, A. S., L.Fong, and Naidu,

S. (2020). An evaluation of online proctoring tools.

International Council for Open and Distance Educa-

tion, 12:509–525.

On the Efficacy of Online Proctoring using Proctorio

289

Hylton, K., Levy, Y., and Dringus, L. P. (2016). Utilizing

webcam-based proctoring to deter misconduct in on-

line exams. Comput. Educ., 92-93:53–63.

Karim, M. N., Kaminsky, S., and Behrend, T. (2014).

Cheating, reactions, and performance in remotely

proctored testing: An exploratory experimental study.

Journal of Business and Psychology, 29:555–572.

Krak, R. and Diesvelt, J. (2016). Pearson Digital Testing

Environment Security Assessment. Technical report,

University of Twente, The Netherlands.

Krak, R. and Diesvelt, J. (2017). Security Assessment of

the Pearson LockDown Browser and MyLabsPlus En-

vironment. Technical report, University of Twente,

The Netherlands.

Lilley, M., Meere, J., and Barker, T. (2016). Remote live in-

vigilation: A pilot study. Journal of interactive media

in education, 2016.

Milone, A. S., Cortese, A. M., Balestrieri, R. L., and Pit-

tenger, A. L. (2017). The impact of proctored on-

line exams on the educational experience. Currents

in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 9(1):108 – 114.

Quickscan SURF (2020). Quickscan privacydocumentatie

online proctoring. Online document, SURF, Nether-

lands. In Dutch.

Vazquez, J. J., Chiang, E. P., and Sarmiento-Barbieri, I.

(2021). Can we stay one step ahead of cheaters? a

field experiment in proctoring online open book ex-

ams. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Eco-

nomics, 90.

Weiner, J. and Hurtz, G. M. (2017). A comparative study of

online remote proctored versus onsite proctored high-

stakes exams. Journal of Applied Testing Technology,

18(1).

Whitepaper SURF (2020). Online proctoring — ques-

tions and answers at remote surveillance. Whitepaper,

SURF, Netherlands. Available here.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

290