Ethical Concerns of the General Public regarding the Use of Robots

for Older Adults

Esther Ruf

a

, Stephanie Lehmann

b

and Sabina Misoch

c

Institute for Ageing Research, OST Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences, Rosenbergstrasse 59,

St. Gallen, Switzerland

Keywords: Ethics, Ethical Concerns, Robot Use, Older Adults.

Abstract: Due to demographic change the proportion of older adults in the population is increasing, which means that

the proportion of people with limitations making it difficult to live independently at home or in institutions is

also increasing. As a nursing shortage is evident today and expected to increase in the coming years, several

strategies are needed to address these challenges. One possibility is the use of robots to support older adults

and their caregivers. Taking ethical considerations into account is an essential task. Agreement with ethical

concerns identified in the literature was surveyed in a Swiss sample. The participants expressed their

agreement with seven predetermined items but to varying degrees. Possible reduced human contact or

problems with sensitive data received the most agreement. Nearly half of the respondents expressed no

concerns about job loss or violation of privacy. Additional concerns that the older adults would be deceived,

their self-determination compromised, or their dignity violated received less agreement. Further ethical

considerations for future studies are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

As demographic change is evident in Europe due to

low birth rates and increased life expectancy (Eatock,

2019), especially in industrialized countries the

proportion of older adults is growing (Vaupel, 2000).

Within a few decades, the proportion of people aged

65 or older is expected to rise from 19.4 % in 2017 to

28.5 % in 2050 in the European Union (EU)

(Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2018). In 30

years, more than a quarter of the population will be

over 65 years and thus in most European countries in

retirement age. Although life expectancy after

retirement differs in EU-countries, it is on average 21

years for women and nearly 17 years for men

(European Data Journalism Network, 2020). With

this increased number of years of life, the number of

years with limitations such as infirmities also

increases (Hautzinger and Reimer, 2007) and

independence in activities of daily living (ADL)

decreases (Eurostat, 2019), leading to an increase in

the need for care (Statista, 2020). Currently, a

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0520-9538

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1086-3075

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0791-4991

shortage of nursing staff has been acknowledged (Die

Presse, 2019), which will increase in the coming

years. Further, in the inpatient geriatric sector staff

shortages, time pressure and a high workload are

evident today (Baisch, Kolling, Rühl, Klein, Pantel,

Oswald and Knopf, 2018). Different strategies are

needed to respond to these developments, and one

possibility is seen in using robots to support older

adults and their caregivers.

Different types of robots are being developed for

use with older adults. These can be divided for

example into rehabilitation robots and socially

assistive robots with the subcategories service and

companion robots (Broekens, Heerink and Rosendal,

2009, p. 94). Robotic systems are developed for older

adults in various settings and for different tasks: at

home or in retirement and nursing homes, to support

activities of daily living (ADL), to maintain

independence and well-being, and to provide

entertainment (Graf, Heyer, Klein and Wallhoff,

2013; Lehoux and Grimard, 2018; Ray, Mondada and

Siegwart, 2008; Stahl and Coeckelbergh, 2016; Wu,

Ruf, E., Lehmann, S. and Misoch, S.

Ethical Concerns of the General Public regarding the Use of Robots for Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0010478202210227

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2021), pages 221-227

ISBN: 978-989-758-506-7

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

221

Wrobel, Cornuet, Kerhervé, Damnée and Rigaud,

2014). Nursing staff in outpatient and inpatient

settings can be relieved by robotic systems by

reducing remote and routine activities and physically

demanding tasks (Becker, Scheermesser, Früh,

Treusch, Auerbach, Hüppi and Meier, 2013).

Relatives could benefit, knowing their relatives in

need of care are entertained and comfortable (Moyle

et al., 2019). This shows that motives for and goals of

robot use can differ. In their review,

Vandemeulenbroucke, Dierckx de Casterlé and

Gastmans (2018) summarize that many studies have

examined how robots can be used for older adults,

how effective they are, what factors influence

acceptance, and attitudes toward socially assistive

robots.

The high-tech-strategy of the federal government

of Germany states that possibilities of robotic

solutions should be exploited, but at the same time,

challenges should not be overlooked (BMBF, 2015).

A mere orientation towards the needs of different

groups is not enough; research and innovation should

also be steered in directions desired by end users and

society (Kehl, 2018).

In addition to technical functionality, social

acceptance is crucial for the diffusion of robots. The

ethical discussion as well as legal and social

implications play a decisive role (Radic and Vosen,

2020; Remmers, 2020). With increasing technical

development and the use of robotic systems for older

adults, there are not only advantages but also

disadvantages (Lehoux and Grimard, 2018), which

particularly raise ethical questions.

Therefore, in addition to questions of usability and

acceptance, the discussion of various ethical aspects

is essential and is being conducted intensively

(Körtner, 2016; Misselhorn, Pompe and Stapleton,

2013; Portacolone, Halpern, Luxenberg, Harrison and

Covinsky, 2020).

One factor to be considered is that older adults

may be a vulnerable group in need of support due to

potential cognitive and physical limitations. The

German Ethics Council (2020) emphasizes "robotics

should fundamentally represent a complementary and

not a substitutive element of care, which must always

be embedded in a personal relationship" (p.13).

In principle, basic biomedical ethical values

(Beauchamp and Childress 2009, from Körtner,

2016) such as protection from harm, care, self-

determination, and justice must also be applied to the

use of robots for older adults. Additional aspects such

as digital ethics which translates existing ethical

standards need to be systematically considered

(BVDW, 2019). With increasing digitization,

recording, and storing data is possible with robots. As

the data collected from older and/or vulnerable adults

is particularly sensitive, it must be protected from

unauthorized access. Only necessary data on the

person in need or on the supporting person should be

collected. Already today, robots must comply with

data protection regulations and are not allowed to

collect and disseminate data without informed

consent (EGE, 2018, p. 22).

In a systematic review for argument-based ethics

publications, it was shown that two different forms of

the ethical debate on care robots use in aged care

exist: an ethical assessment of or an ethical reflection

about care robots (Vandemeulebroucke et al., 2018).

From the point of view of older adults, concerns

could be that they could experience reduced social

and emotional support using robots and could be

subjected to intrusions on their privacy, as well as

being deceived and infantilized. The point of view of

professional caregivers could include a change in

their work towards less relationship-oriented care,

and that the preferred financing of robotic systems is

at the expense of improvements in personnel (instead

of higher remuneration, lower work density, general

upgrading of the nursing profession) (German Ethics

Council, 2020). According to Yew (2020), ethical

challenges in the use of robots in care concern the

extent of care provided by robots, the possibility of

deception of vulnerable individuals, (over)trust and

(over)commitment to robots, the lack of informed

consent, and the potential violation of user privacy.

There is a broad theoretical discussion of the

ethical points with different emphases depending on

the subject area or focus on user groups. To obtain an

initial indication of whether the ethical concerns

regarding the use of robots in the care and support of

older adults that have been frequently mentioned in

the theoretical literature are also considered important

by the population, a survey study was conducted.

2 METHOD

2.1 Recording Ethical Concerns

Data on general ethical concerns were collected as

part of a broad survey on attitudes, wishes and

concerns of Swiss people regarding robot use for

older adults, with a robot acceptance questionnaire

self-developed in 2018. Regarding ethical aspects,

seven items were created that cover the most

frequently mentioned ethical topics in literature

regarding robot use and older adults (Körtner, 2016;

Sharkey and Sharkey, 2012; Sorell and Draper, 2014;

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

222

Vandemeulebroucke et al., 2018): (I) deception, (II)

violation of dignity, (III) restriction of self-

determination, (IV) reduced human contact, (V)

violation of privacy, (VI) problems with sensitive

data, (VII) job loss.

Data were collected via an online and a paper

questionnaire between January 2019 and December

2020. Participants were asked: “If robots are used to

assist in care or service activities with the older

adults, I would have concerns that...” and had to

indicate their agreement on a six-point Likert scale

(1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = somewhat

disagree, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = agree, 6 = strongly

agree). For a detailed description of the overall study,

the entire survey, the item selection process, the

recruitment procedure, and the pretest see Lehmann,

Ruf and Misoch (2020).

2.2 Analysis

In this paper, the results for the seven ethical concern

items are reported. For data analysis IBM SPSS 26

was used. Before analysing data, cases with more than

70 % missings were deleted. Consent to ethical

concerns is shown descriptively (n for sample size, %

for frequencies, M for mean value, SD for standard

deviation), according to the scale level. To determine

agreement or disagreement with a given ethical

concern, the answers "strongly disagree" (1),

“disagree” (2) and “somewhat disagree” (3) were

taken together to calculate disagreement, the answers

“somewhat agree” (4), “agree” (5), strongly agree” (6)

were taken together to calculate agreement. To

analyse differences between two groups regarding

ethical concerns, t-tests were calculated. When

comparing more than one group, one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) was calculated.

2.3 Participants

Until December 2020, 188 persons participated, most

of them used the online version of the questionnaire.

The participants were between 17 and 96 years old

(M = 65,7, SD = 16,7). More women participated

(57,6 %), most were married or living with a partner

(64,5 %) and Swiss (89,4 %). 65,8 % had tertiary

education. Most participants lived in a private

household (96,8 %) consisting of two people (53,7

%). They lived in 14 different cantons, in St.Gallen

(28,2 %), Aargau (20,7 %) and Zurich (18,1 %), 50,3

% rated their residential area as rather rural. 81,8 %

rated themselves as interested or very interested in

technology. 59,7 % had collected more experience

with technology during their life and 41,6 % had

already experience with a robot. Table 1 shows the

characteristics of the study population.

Table 1: Participants.

Variable (n = number)

Gender

(

n = 184

)

57,6 % female

42,4 % male

Marital status

(n = 183)

64,5 % married or living

with a partner

13,1 % single

12,6 % widowed

9,8 % divorced or living

without a

p

artne

r

Nationality

(n = 179)

89,4 % Swiss

10,6 % othe

r

Education level

(n = 184)

65,8 % tertiary level

24,5 % secondary level

9,2 % mandatory school

0,5 % unknown

Occupational field

(current or former)

(n = 187)

44,9 % other field

31,6 % social, nursing, or

medical field

22,5 % technical field

1,1 % not working

Type of living

(n = 185)

96,8 % private household

1,6 % care home

1,1 % other

0,5 % retirement home

Residential area

(

n = 183

)

50,3 % rather rural

49,7 % rathe

r

urban

Interest in technology

(n = 187)

52,4 % yes, interested

29,4 % yes, very interested

14,4 % no, rather less

interested

3,7 % no, not at all

intereste

d

Experience with

technology

(

n = 186

)

59,7 % yes

40,3 % no

Experience with a

robot

(n = 183)

54,6 % no

15,8 % yes, somewhere else

11,5 % yes, at work

7,7 % yes, at a shop, hotel,

restaurant

6,6 % yes, at home

3,8 % don’t know

3 RESULTS

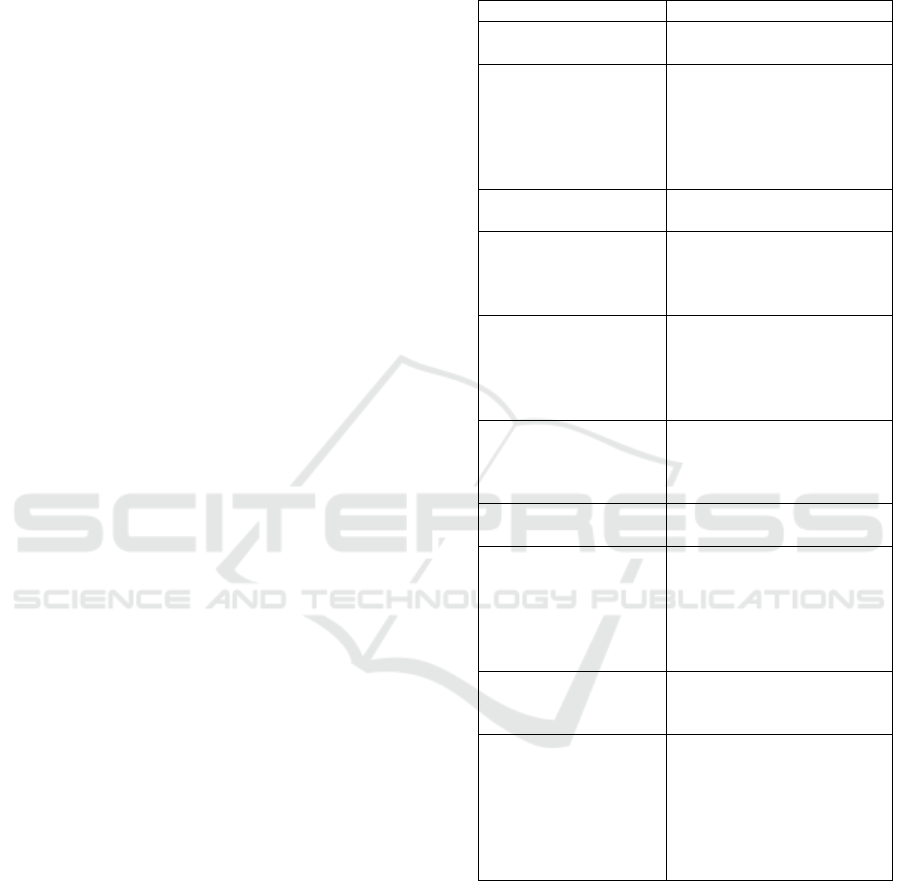

The study population expressed their agreement with

all seven predetermined factors regarding the use of

robots with older adults, but to varying degrees

(figure 1). Agreement with concerns regarding

deception, dignity of older adults, restricted self-

determination, violation of privacy and job loss were

expressed by fewer than 50 % of the study population.

Ethical Concerns of the General Public regarding the Use of Robots for Older Adults

223

76,5 % reported the concern that older adults could

have reduced human contact. 60,4 % reported the

concern that the handling of personal or sensitive data

could cause problems. The strength of agreement

varied (table 2).

Figure 1: Frequencies of ethical concerns of the study

population.

Table 2: Reported ethical concerns.

Number Mean

Standard

deviation

(

I

)

Dece

p

tion 179 3,3 1,3

(II) Violation of

di

g

nit

y

184 3,2 1,4

(III) Restriction of

self-determination

182 3,2 1,4

(IV) Reduced

human contact

183 4,4 1,4

(V) Violation of

p

rivac

y

184 3,5 1,5

(VI) Problems

with sensitive data

182 4,0 1,4

(

VII

)

Job loss 185 3,6 1,6

Comparing male and female participants there

was no significant difference in ethical concerns.

When comparing age-groups (oneway ANOVA with

three age groups: up to 65 years (N = 65), 66-74 years

(N = 63), from 75 years (N = 56)), no statistically

significant differences in means of ethical concerns

could be shown, as well as when comparing

participants with and without interest in technology,

and when comparing participants with and without

technology experience, or when comparing

participants from different professional backgrounds

(oneway ANOVA with four groups: technical field

(N = 42), social field (N = 59), other field (N = 84),

not working (N = 2)).

Regarding participants with and without previous

contact with robots, only the ethical concern “reduced

human contact” was significant. Persons with no prior

contact had more concerns that older adults would

have reduced human contact when robots are used to

support care or service activities for older adults

(table 3).

Table 3: Ethical concerns by participants with and without

prior contact with a robot.

No prior

contact

Prior

contact

t-test

I

M = 3,4

(SD = 1,2;

n = 99)

M = 3,3

(SD = 1,4;

n = 76)

t(144,788) = ,121,

p = ,904

II

M = 3,3

(SD = 1,4;

n = 105)

M = 3,0

(SD = 1,4;

n = 75)

t(178) = 1,271, p

= ,205

III

M = 3,3

(SD = 1,5;

n = 103

)

M = 3,1

(SD = 1,4;

n=75

)

t(176) = ,912, p =

,363

IV

M = 4,6

(SD = 1,3;

n = 103

)

M = 4,1

(SD = 1,4;

n=76

)

t(177) = 2,271, p

= ,024

V

M = 3,6

(SD = 1,4;

n = 105)

M = 3,3

(SD = 1,6;

n = 75)

t(178) = 1,298, p

= ,196

VI

M = 4,0

(SD = 1,3;

n = 103)

M = 4,1

(SD = 1,4;

n = 75)

t(176) = -,228, p

= ,820

VII

M = 3,8

(SD = 1,4;

n = 106)

M = 3,4

(SD = 1,7;

n = 75)

t(179) = 1,744, p

= ,083

4 DISCUSSION

In the present study, ethical concerns of the Swiss

population concerning the use of robots for older

adults were collected based on the main ethical issues

discussed in literature. Ethical concerns with the

highest agreement were reduced human contact and

problems with sensitive data. Nearly half of the

respondents also agreed to concerns about workers

losing their jobs and violation of privacy. Other

expressed agreements were concerns that older adults

would be deceived, their self-determination

compromised, and their dignity violated. However,

this means conversely that for five of the seven

questions, the respondents were ambivalent, with

51−62 % of respondents not agreeing that these issues

were of ethical concern.

Arras and Cerqui (2005) reported that individuals

with more prior knowledge had a more positive

attitude toward robots. In the present study, when

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

224

comparing the agreement to ethical concerns by

participants with and without prior contact with a

robot it seems that real-world contact with robots

lessens the concerns that robot use might reduce

human contact.

The focus of the present study was intentionally

on the general population's viewpoint. The main

ethical points to be assessed were taken from the

literature and theoretical discussions. In doing so, the

results fit with Ray et al. (2008) who found the lack

of interpersonal relationships as negative aspects in

their questionnaire survey (N = 240, 6 % over 65

years). However, it must be considered that there can

be discrepancies between ethical concerns raised in

theory, and those of end users in practice when they

must decide to use or buy a robot. For example, in

their study, Bradwell, Winnington, Thill and Jones

(2020) asked 67 young adults (M = 28 years, SD =

10,99, range 18 – 65) about their concerns after

interacting with four companion robots. When

surveyed with an open-end question, the majority (60

%) reported having no ethical concerns, reduced

human contact was the most likely. However, this

was not evident in the standardised question. The

(younger) participants in the study of Bradwell et al.

(2020) were more concerned about economic issues

and equality of access, as this is an important

consideration for those involved in the care of older

adults. The concerns proposed by ethicists seemed

not to be a barrier to use robots.

Such studies are very important to be able to make

a comparison between what is mentioned as a concern

from a theoretical ethical perspective and what the

actual fears and concerns of the end users are. The

implementation of a robot is more likely to be

determined by the attitudes and concerns of end users,

for example, care facility personnel, the older adults

themselves, or their relatives who purchase a robot.

Some important limitations of the study must be

mentioned. As shown by the sociodemographic data

of the participants, the sample is composed of highly

educated participants with a high interest in

technology and therefore not representative of the

general population. The fact that mainly well-

educated and technology-oriented people participate

in such studies is also known from other studies

(Classen, Oswald, Doh, Kleinemas and Wahl, 2014;

Kubiak, 2015; Mies, 2011; Stadelhofer, 2000).

Further, since it was a questionnaire study the

participants had to make their assessment globally,

without being shown a concrete robot and without

interacting with a robot. This could have influenced

their judgement, and as people have different

backgrounds and experiences, some could have relied

on experience, others only on an internal picture

(Savela, Turja and Oksanen, 2018). Therefore, it

cannot be excluded that the assessments would be

different if a concrete robot or a concrete interaction

or decision had to be assessed. Another limitation was

that there were no open-ended questions where

people could formulate ethical concerns. Thus

important areas beyond those mentioned may have

been overlooked.

To stimulate societal discourse, important ethical

concerns were identified. It became clear that not just

theoretical ethical concerns, but actual concerns and

fears of end users should be considered. For future

research, it would be important to survey specific

ethical concerns of individual user groups and

specific settings or related to specific types of robots,

and to raise these concerns more openly.

Since we noticed that some important issues are

not yet considered, in future projects and studies we

will include five more ethical concerns derived from

discussions with researchers, lawyers, and caregivers:

(1) robots could be hacked; (2) robots could hurt the

older adults; (3) older adults could feel controlled; (4)

caregivers could feel controlled; (5) older adults

could be afraid of the robot. In addition, inequality in

terms of financial possibilities should be considered.

Interviewing end users will ensure that they have the

opportunity to formulate and express their concerns

freely.

Moreover, it is necessary to consider ethical

aspects at the stage of programming and designing

robots (Yew, 2020). The robot’s potential actions and

decisions must be based on a basic ethical framework

and the robot must also learn ethical values through

interaction with its environment. Ethical guidelines,

standards and regulations specifically related to the

design of robots and other artificial intelligent

systems are available from the European Commission

(2020).

REFERENCES

Arras, K. O. & Cerqui, D. (2005). Do we want to share our

lives and bodies with robots? A 2000 people survey.

Technical Report, 0605-001. ETH Zürich. Zürich.

https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-010113633

Baisch, S., Kolling, T., Rühl, S., Klein, B., Pantel, J.,

Oswald, F. & Knopf, M. (2018). Emotionale Roboter

im Pflegekontext. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und

Geriatrie, 51(1), 16-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s00391-017-1346-8

Becker, H., Scheermesser, M., Früh, M., Treusch, Y.,

Auerbach, H., Hüppi, R. A. & Meier, F. (2013). Robotik

in Betreuung und Gesundheitsversorgung. TA-SWISS /

Ethical Concerns of the General Public regarding the Use of Robots for Older Adults

225

Zentrum für Technologiefolgen-Abschätzung, 58.

https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-007584670

BMBF (2015). Technik zum Menschen bringen;

Forschungsprogramm zur Mensch-Technik-

Interaktion. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from

https://www.bmbf.de/pub/Technik_zum_Menschen_br

ingen_Forschungsprogramm.pdf

Bradwell, H. L., Winnington, R., Thill, S. & Jones, R. B.

(2020). Ethical perceptions towards real-world use of

companion robots with older people and people with

dementia: survey opinions among younger adults. BMC

Geriatrics, 20(1), 244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-

020-01641-5

Broekens, J., Heerink, M. & Rosendal, H. (2009). Assistive

social robots in elderly care: a review.

Gerontechnology, 8(2), 94-103.

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (2018). Altersstruktur

und Bevölkerungsentwicklung. Retrieved January 15,

2021, from https://www.bpb.de/ nachschlagen/zahlen-

und-fakten/europa/70503/altersstruktur#:~:text=Bezoge

n%20auf%20die%2028%20Staaten,auf%2028%2C5%2

0Pro-zent%20erh%C3%B6hen

Bundesverband Digitale Wirtschaft (BVDW) e.V. (2019).

Mensch, Moral, Maschine. Digitale Ethik, Algorithmen

und künstliche Intelligenz. Retrieved January 15, 2021,

from https://www.bvdw.org/fileadmin/bvdw/upload/

dokumente/BVDW_Digitale_Ethik.pdf

Classen, K., Oswald, F., Doh, M., Kleinemas, U. & Wahl,

H.-W. (2014). Umwelten des Alterns: Wohnen,

Mobilität, Technik und Medien. Kohlhammer. Stuttgart.

Die Presse (2019). Dieses Europa braucht Pflege!

Retrieved January 15, 2021, from

https://www.diepresse.com/5670909/dieses-europa-

braucht-pflege

Eatock, D. (2019). Demografischer Ausblick für die

Europäische Union 2019. Retrieved November 18,

2020, from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/

etudes/IDAN/2019/637955/EPRS_IDA(2019)637955_

DE.pdf

Europäische Gruppe für Ethik der Naturwissenschaften und

der neuen Technologien (EGE) (2018). Erklärung zu

künstlicher Intelligenz, Robotik und „autonomen“

Systemen. Retrieved Januar 15, 2021, from

https://ec.europa.eu/research/ege/pdf/ege_ai_statement

_2018_de.pdf

European Commission (2020). Ethics guidelines for

trustworthy AI. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from

https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/ethi

cs-guidelines-trustworthy-ai

European Data Journalism Network (2020).

Lebenserwartung nach der Rente – Ein sehr

unausgeglichenes Europa. Retrieved January 15, 2021,

from https://www.europeandatajournalism.eu/ger/Na

chrichten/Daten-Nachrichten/Lebenserwartung-nach-de

r-Rente-Ein-sehr-unausgeglichenes-Europa#:~:text=We

nn%20das%20Rentenalter%20aber%20angehoben,67%

20(Griechenland)%20f%C3%BCr%20M%C3%A4nner

Eurostat (2019). Difficulties in personal care activities by

sex, age and educational attainment level. Retrieved

November 18, 2020, from https://appsso.eurostat.ec.

europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=hlth_ehis_pc1e&lang=

en

German Ethic Council (2020). Robotik für gute Pflege.

Stellungnahme. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from

https://www.ethikrat.org/fileadmin/Publikationen/Stell

ungnahmen/deutsch/stellungnahme-robotik-fuer-gute-

pflege.pdf

Graf, B., Heyer, T., Klein, B. & Wallhoff, F. (2013).

Servicerobotik für den demographischen Wandel.

Mögliche Einsatzfelder und aktueller

Entwicklungsstand. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-

Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 56(8), 1145-

1152.

Hautzinger, M. & Reimer, C. (2007). Psychotherapie alter

Menschen. In Reimer, C., Ecker, J., Hautzinger, M.,

Wilke, E. (Eds.), Psychotherapie. Ein Lehrbuch für

Ärzte und Psychologen (pp. 631-648). Springer.

Heidelberg, 3

rd

edition.

Kehl, C. (2018). Wege zu verantwortungsvoller Forschung

und Entwicklung im Bereich der Pflegerobotik: Die

ambivalente Rolle der Ethik. In Bendel, O. (Ed.),

Pflegeroboter (pp. 141-160). Springer Gabler.

Wiesbaden.

Körtner T. (2016). Ethical challenges in the use of social

service robots for elderly people. Ethische

Herausforderungen zum Einsatz sozial-assistiver

Roboter bei älteren Menschen. Zeitschrift fur

Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 49(4), 303-307.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-016-1066-5

Kubiak, M. (2015). Ist Beteiligung immer gut und sinnvoll?

Partizipation und/oder politische Gleichheit. Impu!se

88, 4-5.

Lehmann, S., Ruf, E. & Misoch, S. (2020). Robot use for

older adults – attitudes, wishes and concerns. First

results from Switzerland. In Stephanidis, C., Antona,

M. (Eds.), HCI International 2020 – Posters. HCI 2020.

Communications in Computer and Information

Science, vol 1226, Part III (pp. 64-70).

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50732-9_9

Lehoux, P. & Grimard, D. (2018). When robots care: Public

deliberations on how technology and humans may

support independent living for older adults. Social

Science & Medicine, 211, 330-337.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.038

Mies, C. (2011). Akzeptanz von Smart Home Technologien:

Einfluss von subjektivem Pflegebedarf und

Technikerfahrung bei älteren Menschen. Untersuchung

im Rahmen des Projekts «Accepting Smart Homes».

Diplomarbeit. Wien.

Misselhorn, C., Pompe, U. & Stapleton, M. (2013). Ethical

Considerations Regarding the Use of Social Robots in

the Fourth Age. GeroPsych: The Journal of

Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(2),

121. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000088

Moyle, W., Bramble, M., Jones, C. & Murfield, J. E.

(2019). “She had a smile on her face as wide as the

Great Australian Bite”: A qualitative examination of

family perceptions of a therapeutic robot and a plush

toy. The Gerontologist, 59(1), 177-185.

https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx180

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

226

Portacolone, E., Halpern, J., Luxenberg, J., Harrison, K. L.

& Covinsky, K. E. (2020). Ethical issues raised by the

introduction of artificial companions to older adults

with cognitive impairment: A call for interdisciplinary

collaborations. Journal of Alzheimer's disease: JAD,

76(2), 445-455. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190952

Radic, M. & Vosen, A. (2020). Ethische, rechtliche und

soziale Anforderungen an Assistenzroboter in der

Pflege. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 53,

630-636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-020-01791-6

Ray, C., Mondada, F. & Siegwart, R. (2008). What do

people expect from robots? In Proceedings of the

IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent

Robots and Systems (pp. 3816-3821). IEEE. Nice.

Remmers P. (2020). Ethische Perspektiven der Mensch-

Roboter-Kollaboration. In Buxbaum, H. J. (Ed.),

Mensch-Roboter-Kollaboration. Springer Gabler.

Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-28307-

0_4

Savela, N., Turja, T. & Oksanen, A. (2018). Social

acceptance of robots in different occupational fields: a

systematic literature review. International Journal of

Social Robotics 10(4), 493-502.

Sharkey, A. & Sharkey, N. (2012). Granny and the robots:

ethical issues in robot care for the elderly. Ethics and

Information Technology, 14, 27-40.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-010-9234-6

Sorell, T. & Draper, H. (2014). Robot carers, ethics and

older people. Ethics and Information Technology, 16,

183-195.

Stadelhofer, C. (2000). Möglichkeiten und Chancen der

Internetnutzung durch Ältere. Zeitschrift für

Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 33, 186-194.

Stahl, B. C. & Coeckelbergh, M. (2016). Ethics of

healthcare robotics: Towards responsible research and

innovation. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 86,

152-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2016.08.018

Statista (2020). Prognostizierter Anstieg von

Pflegebedürftigkeit nach Weltregion im Zeitraum von

2010 bis 2050. Retrieved December 02, 2020, from

https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/274042/u

mfrage/prognostizierter-anstieg-von-

pflegebeduerftigkeit-nach-weltregion/

Vandemeulebroucke, T, Dierckx de Casterlé, B. &

Gastmans, C. (2018). The use of care robots in aged

care: A systematic review of argument-based ethics

literature. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 74,

15-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2017.08.014

Vaupel, J. (2000). Setting the stage: a generation of

centenarians? The Washington Quarterly, 23(3), 197-

200.

Wu, Y.-H., Wrobel, J., Cornuet, M., Kerhervé, H., Damnée,

S. & Rigaud, A.-S. (2014). Acceptance of an assistive

robot in older adults: a mixed-method study of human-

robot interaction over a 1-month period in the Living

Lab setting. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 801-811.

Yew, G. C. K. (2020). Trust in and ethical design of

carebots: The case for ethics of care. International

Journal of Social Robotics, 1-17.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00653-w

Ethical Concerns of the General Public regarding the Use of Robots for Older Adults

227