Stressed by Boredom in Your Home Office? On „Boreout“ as a

Side-effect of Involuntary Distant Digital Working Situations on

Young People at the Beginning of Their Career

Ioannis Starchos

and Anke Schüll

a

Department of Business Information Systems, University of Siegen, Kohlbettstr. 15, Siegen, Germany

Keywords: Boreout, Crisis of Meaning at Work, Crisis of Growth, Job Boredom, Connectivity, Home Office.

Abstract: The main focus of this paper is on boredom and boreout perceived by working novices driven into home

office due to the covid-19-pandemic. Because this situation is exceptional, the impacts on a crisis of meaning,

job boredom and a crisis of growth manifest themselves more clearly. Young people are the unit of interest

within this paper, as a boreout could be devastating for their professional career. Leaning on recent literature,

a qualitative analysis was conducted, followed by an anonymous online survey to test the viability of the

approach. Only spare indicators for a crisis of meaning were identified, clear signals pointing towards

boredom and strong indicators for a crisis of growth as well as evidence for coping strategies relying on

various communication tools to compensate the lack of personal contact. This paper contributes to the body

of knowledge by expanding research on boreout and by underlining the importance of its dimensions crisis of

meaning, job boredom and crisis of growth. A moderating effect of IT-equipment and IT-support on

establishing and maintaining connectivity in distant digital working situations became evident. This paper

reports on work in progress, further research would be necessary to confirm the results.

1 INTRODUCTION

Spurk and Straub (2020) point out, that the pandemic

and its consequences can affect working conditions,

work motivations and behavior, job and career

attitudes, career development, and personal health

and well-being. Due to the recency of the pandemic,

its impact on employees is yet underexplored, results

of actual studies contradictory. Dubey and Tripathi

(2020) e.g. report on a sentiment analysis conducted

on 100000 tweets worldwide, identifying a positive

attitude towards working from home, while a lack of

work motivation became evident within a study

among indonesian teachers (Purwanto et al. 2020).

Within this paper, we elaborate on possible negative

effects of digital distant working situations. We aim

to contribute to the body of knowledge by focussing

on boredom as a side-effect of home-offices due to

the covid-19-pandemic.

The pandemic drove employees into home offices

and changed their working situations decisively.

Access to job resources is suddenly blocked,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9423-3769

technological equipment is poorer than at work,

interaction with co-workers limited. In digital distant

working situations, feedback from superiors and co-

workers is reduced, acknowledgement of

achievements is less noticeable. And even though

neither the amount of work nor the complexity of the

tasks necessarily changes with a shift towards home

offices, a lack of excitement, of challenge, of

competition and of team spirit could lead to job

boredom.

Boredom can be understood as a negative

psychological state of unwell-being (Reijseger et al.

2013), that can even turn into an phenomenon called

“boreout” (Stock 2015). In contrast to “burnout”, its

counterpart “boreout” is still underexplored.

Triggered by a crisis of meaning, job boredom and a

crisis of growth, boreout goes along with

demotivation, a lack of coherence and a loss of

purpose (Stock 2015).

Even though these stressors affect employees in

any stadium of their working life, young people at the

beginning of their careers are the focus of our interest.

Starchos, I. and Schüll, A.

Stressed by Boredom in Your Home Office? On „Boreout“ as a Side-effect of Involuntary Distant Digital Working Situations on Young People at the Beginning of Their Career.

DOI: 10.5220/0010479405570564

In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2021) - Volume 2, pages 557-564

ISBN: 978-989-758-509-8

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

557

In this stage of working life, boreout could have a

serious impact on these young people’s careers and it

is in their interests as well as in those of their

employers, to deal with the working situation

accordingly. Exploring the impact of involuntary

distant working situations on “boreout” as a negative

psychological state of young people at the beginning

of their career, is therefore the focus of this study.

2 RELATED LITERATURE

Boredom at work can be understood as a negative

psychological state of low internal arousal and

dissatisfaction (Reijseger et al. 2013). In its extreme,

“Boreout” manifests itself in a crisis of meaning at

work, job boredom, and content plateauing, also

referred to as a crisis of growth (Stock 2013, 2015).

In contrast to “burnout”, its counterpart “boreout” is

still underexplored.

A sense of coherence in working environments is

built on a perception of comprehensibility,

manageability, and meaningfulness (Antonovsky

1988). Comprehensibility points towards the working

situation being structured, clear and consistent.

Manageability addresses the availability of job

resources to cope with job demands and

meaningfulness indicates the perceived value and

sense of the assigned tasks (Jenny et al. 2017).

According to Kompanje (2018), boreout as well

as burnout are rooted in a crisis of meaning. He posits

a basic need of a person to believe, that what this

person does is important, makes sense and is

significant (Kompanje 2018). If people lose this

believe, their capability to cope with difficult working

situations is restricted, they might even crash

(Kompanje 2018). A recent study confirmed a

positive association of boreout with depression,

anxiety and stress (Özsungur 2020a).

As loss of meaning, lack of excitement and of

personal development correspond with loss of valued

resources, the main effects of boreout can be

explained by the conservation of resources (COR)

theory (Stock 2016). The COR theory was introduced

by Hobfoll (Hobfoll 2001; Hobfoll et al. 2018).

According to this theory, the loss or anticipated loss

of valued resources causes mental strain (Stock

2016). Compared to job demands, job resources are

more stable (Brauchli et al. 2013), or rather: they

were, until the covid-19-pandemic turned this upside

down.

The salutogenic model, or the model of

salutogenesis defined by Antonovsky, underlines the

importance of coherent experiences (Antonovsky

1991, 1979). A sense of coherence influences how an

employee makes use of the available job resources

and can cope with stressors in working-life (Jenny et

al. 2017). A good sense of coherence can protect

employees from negative aspects of working

conditions (Feldt 1997). Jenny et al. (2017) point out,

that this mechanism is reciprocal: building and

maintaining job ressources enables employees to

develop coping strategies and to put them into action.

Losing this sense of coherence can lead to a „crisis of

meaning“ and can even affect the health of an

employee. Kempster et al. (2011) put the task of

building meaningful working situations into the

responsibility of management.

Boredom as a lack of internal arousal due to

understimulating working environments leads to

dissatisfying working experiences (Reijseger et al.

2013). According to Stock (2015) a lack of

excitement and on-the-job challenges can have a

demotivating effect. Habituation increases and

creativity impedes (Stock 2013). Evidence for

boredom are daydreaming, task-unrelated thoughts,

or work-unrelated tasks, inattention or a distorted

perception of time dragging along (Reijseger et al.

2013).

Jessurun et al. (2020) introduced the concept of

relative underperformance and chronic relative

underperformance and aligned both to a person-

environment-misfit. Relative underperformance

addresses a state of being, in which the performance

stays underneath a persons’ level of abilities. In

relation to what they could do, they fall behind. This

state is acquired, develops over time and can turn

chronic, if permanent (Jessurun et al. 2020).

But as an unpleasant state, boredom can also have

a positive effect: it promotes movement, urges the

need to take action, to escape this uncomfortable

situation (Jessurun et al. 2020). If this urge to actively

move away from a dissatisfying working situation is

inhibited, this person is stuck within this state and

might even switch into a paradox behaviour by

actively maintaining the situation (Rothlin und

Werder 2007). This would indicate a boreout, so job

boredom is a precursor of boreout (Jessurun et al.

2020).

Another dimension of boreout is a crisis of growth

(Stock 2015). If the perspective of gaining

knowledge, learning and personal development is

restricted, motivation decreases (Özsungur 2020b).

A lack of challenge can initiate a crisis of growth,

which can lead to a crisis of meaning. A crisis of

meaning can be related to boredom. The three

dimensions are thus not independent, but related to

each other.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

558

Within this pandemic, access to job resources is

blocked, technological equipment in home office is

poorer than at work, interaction with co-workers

limited. On the same hand, the limited control offers

more autonomy. We focus on working novices, as a

boreout at this very early stage could have a negative

impact on their professional career.

3 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

Informed by literature, we conducted a qualitative

analysis as a preliminary step to building our

hypotheses. Due to the situation, the interviews had

to be conducted by telephone or video conference.

The distance subdued the interviewees being

influenced, therefore we drew up a guideline for the

semi-structured interviews.

As ambitious young people at the beginning of

their careers are the units of our interest, interviewees

were selected among the target group of trainees,

interns and student workers (age 20-24 years, mixed

sex), that were sent into home office. They were

selected from different lines of work: Mechanical

engineering, automotive, advertising, financial

services and service providers, but all engaged in IT-

supported tasks.

Five semi-structured interviews were conducted

lasting 25-45 minutes. Linking the responses to the

dimensions of boreout and grouping them into

themes, led to six categories:

Crisis of meaning,

Job boredom,

Crisis of growth,

Connectivity,

IT equipment and IT support and

Benefits.

Table 1: Sample statements on a crisis of meaning.

I4

“This is not what I wanted, what I imagined.

There is a lot missing, that made this profession

special and I know that many colleagues and

friends feel the same wa

y

.”

I5

“I get along very well with my team. I get along

very well with my direct supervisor. And the fact

that some of that has disappeared means that, the

only thing that remains is work. Only what you

actually are paid for […] I think that makes the

work less rewardin

g

.”

Even though the discontent is palpable, the

interviews gave only spare indication of a crisis of

meaning. The tasks were comparable to the tasks

assigned before. Neither quantity nor quality changed

significantly. Initial problems in task assignment

were solved after a short period of time: “In the

beginning, I didn't have many tasks. It was just: I was

sitting at the PC, I was online when something was

going on, but I didn't really work on anything and

there I would say that I was underchallenged during

that time.” (I2) While indicators for a crisis of

meaning were spare, signals for boredom became

more evident.

Table 2: Sample statements on job boredom.

I1

“You spend more time on everyday chores, less

on the bigger and more challenging tasks. […]

You feel a bit, I wouldn't say underchallenged,

b

ut the tasks are a bit monotonous.”

I2

“However, because I don't have to take the

subway or train in the morning, I am in front of

my laptop earlier and start earlier, but it takes me

lon

g

er until I actuall

y

reall

y

do somethin

g

.”

I3

“You have a bit of a feeling that time has

sto

pp

ed.”

I3

“When you work at home, it happens quite

quickly that you are distracte

d

”

I4

“Procrastination is definitely a thing and also the

lack of contacts.”

I4

“Yes, you spend more time on fewer tasks. So I

often needed more attem

p

ts for one thin

g

.”

I5

“Due to the fact that the work is currently more

monotonous, if you do the same thing over and

over again, then you get bored or I get more

b

ored.”

Commenting on a feeling, that time had stopped

(I3) addresses a distorted perception of passing time,

indicating boredom (Reijseger et al. 2013).

Distraction, procrastination, work unrelated tasks,

monotony and boredom were mentioned by all five

interviewees. As the pandemic caused massive

restrictions in the working situation plus the private

situation, the combination adds up to the discontent:

“It somehow doesn't feel as satisfying anymore when

you finish the eight hour day because you can't do

anything after that anyway.” (I4)

Our special interest was on a crisis of growth, as

this would be devastating for young ambitious people

in the early stages of their working life. The

interviewees experienced this very differently. I5

postponed his intention to pick-up studies at a

university. He commented on a decreased mood:

“Yes, but this is not directly due to the job. I think it's

more due to the duration. It's been going on for

months now. […] This, of course, makes for a

diminished quality of life.” (I5)

Stressed by Boredom in Your Home Office? On „Boreout“ as a Side-effect of Involuntary Distant Digital Working Situations on Young

People at the Beginning of Their Career

559

Table 3: Sample statements on a crisis of growth.

I3

“In general, I still learn a lot on the work I do.

Especially as a student it is extremely valuable to

have such experiences and I am therefore very

grateful anyway and very satisfied.”

I4

“The contact is not so direct, and I find that if

you don't know the people well, it's […] more

distant. You might be more inhibited to ask

something, especially if you're new to the

department or the office.”

I4

“I had the feeling I dared much less. So my

feedback has actually gotten worse because of

that.”

I4

“We have an "academy of knowledge" almost

every week where someone from the industry is

invited or marketers are invited, to present

themselves and give their presentations for

trainin

g

or for marketin

g

p

ur

p

oses.”

I5

“For me specifically in marketing, of course, it's

the case: this is a profession that is extremely

communicative. That is now completely gone.

There's no exchange at all anymore, and that

naturally has an impact. Both personally and

professionally. That means that you could even

call it professionally limiting.”

Table 4: Sample statements on connectivity.

I2

“We often take a coffee break together or

something like that. And we chat a lot, yes. So I

still feel like part of the team.”

I3

“I think building social contacts is relatively hard

online. You can maintain them, if you have

already met people, but online people simply

don’t walk

b

y and

p

op in and say "hello".”

I3

“It's always easier to go straight over and talk in

person than to write an email or arrange a call for

the next day. It always seems to take a little time

ri

g

ht now.”

I4

“I have the feeling that, through

videoconferences or other media, there are often

misunderstandings and then I ask things and then

I do things the way I think they were told to me

and afterwards they say, "Well, that's completely

wrong. I told you that, didn't I? What's going

on?" And I think that a lot of it is also due to this

lack of inter

p

ersonal contact.”

I4

“We have a rotation principle. That means we're

in new departments every four months, and I

have to say, in all my last departments, all during

the Corona crisis, I felt my connectivity was very

low.”

I4

“So yes, I can say that you can feel left alone as a

trainee.”

“I had the feeling I dared much less.” (I4) points

towards a relative underperformance (Jessurun et al.

2020), that I4 is well aware of and discontent with.

Interviewee 2 mentioned a lack of acknowledgement:

“Maybe it is less, because the co-workers just

acknowledge it less or generally see less. In the end,

they only see the result, and even that is not

necessarily the case. Yes, the others just don't see it

anymore.” The perception of results remaining

unseen and achievements going unnoticed could

indicate a crisis of growth, but the interviewee denied:

“Personally, that's not so important to me. First and

foremost I do it for myself.” (I2).

But the degree to which a person perceives to be

valued by their supervisors, takes influence on their

innovative work behaviour (Stock 2015). Jessurun et al.

(2020) describe “not been seen” as a major stressor,

capable to undermine the attachment system and to sow

doubts into an otherwise self-confident person.

The aforementioned statements referred to

connectivity as a major issue. The statements

underlined the importance of social interaction for

these young people and the difficulties they face in

building up new working contacts, to help them cope

with on-the-job challenges. Interviewee 2 pointed in

a similar direction: “And the distant working often

gives you the feeling that the supervisors don't have

much time or are annoyed when one of us wants

something.” (I2) Following up on this, the

interviewee was asked if “annoyance” was more

frequent, he commented: “Because of the home

office, yes, because you can't assess the mood as well

as you can face-to-face. You can more easily tell

whether there is time for you at the moment or not.”

In Reijseger et al. (2013) evidence was found, that

unsupportive and uncooperative co-workers are

positively related to job boredom, declaring the social

context as a risk factor for boredom.

As the company of interviewee 2 found ways to

compensate the lack of personal interaction, the

feeling of isolation was prevented: “I wouldn't say

that, because we often take a coffee break together or

something like that. And we chat a lot, yes. So I still

feel like part of the team.” (I2). This statement gives

evidence for the necessity to offer a digital surrogate

to compensate the lack of personal communication.

IT-equipment & support are basic resources to

fulfill the assigned tasks. As the interviews gave

evidence for coping strategies relying on digital

surrogates to compensate the lack of personal contact,

the importance goes beyond the basic necessity. Even

though mandatory, an adequate IT infrastructure in a

home office can’t always be taken for granted.

Purwanto et al. (2020) dedicated the main part of their

discussion of negative impacts of “work from home”

within the covid-19-pandemic to technical

equipment, advocating an additional budget to cover

the increased costs for electricity and internet.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

560

Table 5: Sample statements on IT equipment and IT

support.

I2

“The company was well prepared. Just about

every employee got two notebooks to take home

and also the opportunity to still work at the

com

p

an

y

if the

y

reall

y

wanted to.”

I2

“However, because I work at home, there is less

space, and also no extra monitor anymore. This

makes workin

g

a bit more difficult sometimes.”

I3

“I have always had a work laptop and VPN

access. Accordingly, the infrastructure for home

office has always been there. At the same time,

we had […] as a communication and a video

conferencing tool”

I5

“We are all equipped with mobile devices and

have a VPN network.”

I3

“[…] especially during the first lockdown the

VPNs were simply overloaded and then a new

node was set up relatively quickly […] so that all

p

eople could continue to work again.”

I2

“We have our internal tool. I can write a lot with

colleagues there, or some employees meet with

their boss for coffee breaks and the like. We

students also have a monthly lunch together

every Tuesday. So I certainly don't feel so

isolated”

Within their study of 100000 tweets on “work at

Home” conducted in the beginning of the covid-19-

pandemic, Dubey and Tripathi (2020) found the

majority of tweets worldwide dominated by trust,

anticipation and joy, giving evidence for people

looking forward to working from home. Several

month into the pandemic, this positive attitude is

unbroken. When asked if the interviewees would

proceed working from home voluntarily afterwards,

I1 agreed: “Yes, indeed. You realize that you have

tasks that you can do best at home, or even better,

because it is quieter there. But not full-time. You need

the one, two, maybe even three days a week in the

company. Simply because you also learn more about

things that happen internally and you can talk

properly with your colleagues again.” (I1)

Table 6: Sample statements on perceived benefits of the

working situation.

I3

“I simply realized that when I'm here and I'm

stuck on a problem, that I just can say, “Okay.

I'm taking a break for half an hour. […] And I

have noticed that often in these breaks some

ideas come u

p

on how to solve this

p

roblem.”

I5

“And on the other hand, the concentration at

home, at least with me, is higher, because you are

in your comfort zone and can concentrate fully

on your work.”

4 RESEARCH MODEL

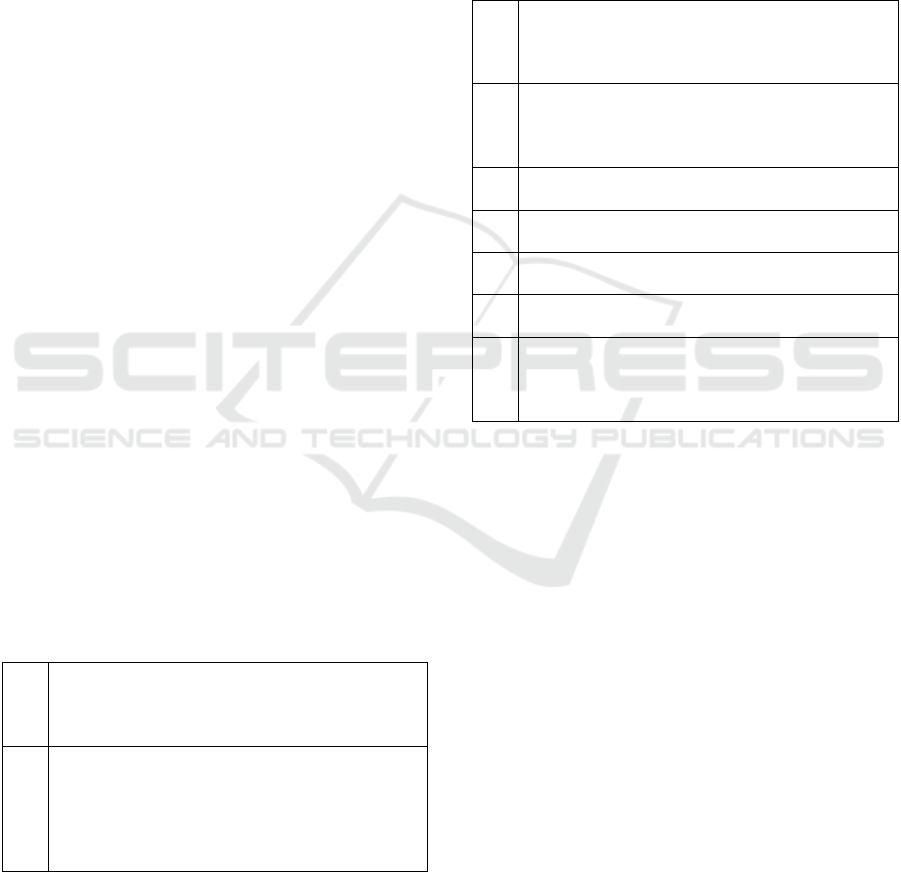

Figure 1: Research model.

The research model is leaning on Stock (2013, 2015,

2016) and was informed by these interviews.

Kompanje (2018) points out the importance to

consider working activities as meaningful, important

and of relevance. If the tasks don’t make sense or

seem insignificant, motivation decreases. Stock

(2013) coined the term “crisis of meaning at work”

for this and identified it as one of three dimensions

pointing towards boreout. In involuntary digital and

distant working situations the feedback from

superiors and co-workers is reduced,

acknowledgement of achievements less noticeable.

Especially young people, whose professional self-

confidence is yet to be developed, are prone to

develop a crisis of meaning under these

circumstances, promoting a boreout (H

1

).

Even though neither the amount of work nor the

complexity of the tasks necessarily changes with a

shift towards distant digital working, a lack of

excitement, of challenge, of competition and of team

spirit could lead to job boredom. According to (Stock

2015) a lack of excitement and on-the-job challenges

can have a demotivating effect. Habituation increases

and creativity impedes. Job boredom is another

dimension of boreout (H

2

) (Stock 2015).

Young people at the beginning of their working

life are ambitious to grow within their working

environment. In digital distant working situations,

participating in the working routines of superiors and

co-workers is limited and errors occurring during the

learning process are less easily detected. If working

in home-office is perceived to slow down the learning

curve, this can lead to a “crisis of growth” (Stock

2013), favouring the occurrence of a boreout. This

crisis of growth affects especially the ambitious and

talented novices, whose hunger to prove themselves

is more difficult to satisfy in digital distant working

situations. A lack of opportunities to go beyond the

expectations of superiors and co-workers and a lack

Boreout

Crisis of meaning

at work

Job Boredom

Crisis of growth

H

1

H

2

H

3

H

4

IT equipment

& support

Stressed by Boredom in Your Home Office? On „Boreout“ as a Side-effect of Involuntary Distant Digital Working Situations on Young

People at the Beginning of Their Career

561

of challenges and stimulation could foster

dissatisfaction and boreout (H

3

).

IT-equipment & support are basic resources to

complete the assigned tasks. As the interviews gave

evidence for coping strategies relying on digital

surrogates to compensate the lack of personal contact,

the importance goes beyond the basic necessity

towards a moderating effect (H

4

).

5 QUALITATIVE ANANYSIS

As the covid-19-induced working situation is without

precedence, the questionnaire (Appendix) was only

loosely oriented on the Boredom scale (Stock 2015)

and the Dutch Boredom Scale (Reijseger et al. 2013).

An anonymous online survey was conducted as a pre-

test for a broader survey. Questions to assess the

workspace environment were followed by statements

with a five-point Likert scale and space for additional

comments. The housing situation (single, family,

children to care for) points towards possible

distractions. The aforementioned six categories

(crisis of meaning, job boredom, crisis of growth, IT

equipment and support, connectivity and benefits)

defined the structure of the survey. All headers within

were dismissed, to prevent terms like “crisis”

influencing the interviewees.

A convenience sample of 65 datasets was

collected, 25 of which were dismissed because the

participants didn’t switch to home office during

covid-19-pandemic. 77.5% of the remaining 40

participants were 20-30 years old. Due to the sample

size, overstretching the interpretation would be

inappropriate, therefore we conducted no in-depth

analysis on these data sets.

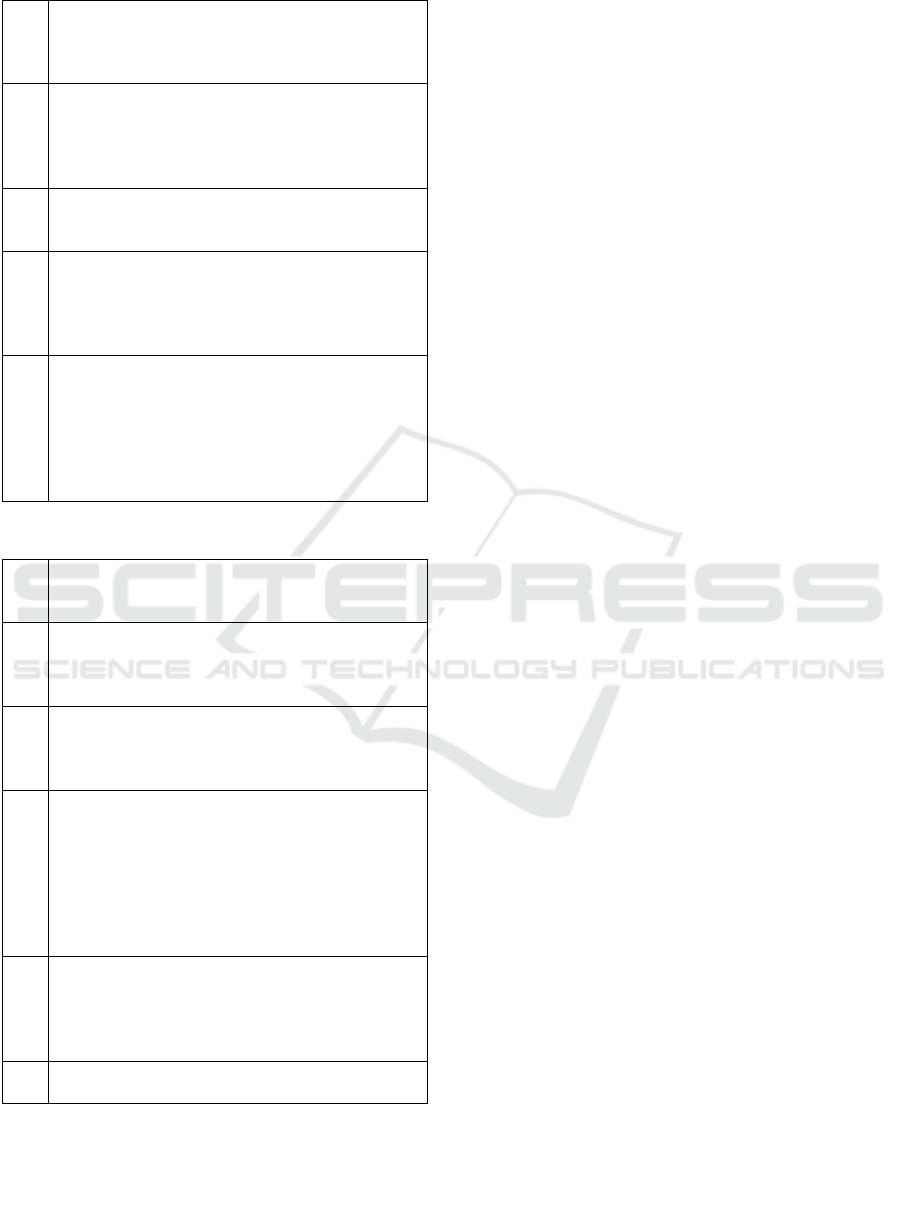

Table 7: Percentages of mentionings.

H1

While the majority of respondents (85%) say

they have less contact with their colleagues and

superiors, only 32.5% feel left alone by their

employer or no longer feel part of a team. A

large proportion (60%) still receive a similar

amount of recognition for work performed as

b

efore the

p

andemic.

H2

Although the majority of respondents (62.5%)

stated that they do not work more slowly in the

home office, an equally large proportion (62.5%)

devote more time to private matters during

regular working hours. For most of the

participants neither the scope of tasks (67.5%)

nor the difficulty (77.5%) has changed and they

have no problems with organizing their daily

work autonomously (62.5%). 65% feel neither

b

ored nor unde

r

-challen

g

ed in home office.

H3

Interest and opportunities for professional

development have not decreased for 77.5% and

a vast majority (92.5%) can turn to colleagues

and supervisors for help. A limitation of work

processes was an issue for 45% and no issue for

47.5%. Half of the respondents claimed,

creativity and morale had suffered as a result of

isolation, while 35% tended to notice no change

in this regar

d

.

H4

Employers have prepared and planned the

transition to the home office in a structured

manner in 70% of cases. The IT equipment has

ensured that 92.5% of employees can do their

work easily. For 77.5% digital surrogates

avoided feelin

g

isolated.

The results of this pre-test gave insights on

necessary minor adjustments to the questionnaire, e.g.

the change of the header, to keep it neutral ( “Job

satisfaction within the Covid-19-pandemic”) and the

use of inverted statements, to avoid bias.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The main focus of this paper was on boredom and

boreout perceived by young people driven into home

office due to the covid-19-pandemic. In home-offices

the degree of them participating in the working

routines of co-workers is limited and errors occurring

during the learning process are less easily detected.

They are less experienced in developing coping

strategies and have a smaller network of professional

contacts to carry them through. The aim of this paper

was to gain insight on boreout within this specific

situation on young people, to assist in mitigating its

effect and to provide assistance in overturning it into

fulfilling and satisfying digital working environments

on a long-term basis. We contribute to the body of

knowledge on job boredom and boreout by

underlining the importance of the three dimensions as

early indicators for boreout and of the moderating

effect of IT-equipment and IT-support on establishing

and maintaining connectivity.

Leaning on recent literature a qualitative analysis

was conducted, that was used to derive a research

model. An anonymous online survey was conducted

to test the viability of our approach. To our relief, the

initial hypothesis, that the digital distant working

situation induced by the covid-19-pandemic would

initiate a crisis of meaning, job boredom and a crisis

of growth, thus would lay the ground for a boreout,

could not be verified within our sample. Neither the

qualitative nor the quantitative survey gave evidence

for a boreout. Only spare indicators for a crisis of

meaning were found, clear signals pointing towards

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

562

boredom and strong indicators for a crisis of growth.

This crisis of growth is palpable and leads to

discontent and frustration within the target group of

young people at the beginning of their working life.

A lack of connectivity was identified as a main issue.

Intensified digital communication compensated the

lack of personal communication and mitigated the

negative effects.

The results show that all interviewees and almost

all respondents to the online survey stated that they

would like to continue or work more often in a home

office after the pandemic at will. In particular,

advantages such as the elimination of commuting, the

better combination of leisure and work, and

sometimes even higher productivity were given as

reasons.

The interviews and the anonymous survey pointed

towards the importance of digital surrogates to

mitigate the negative effects. Coping strategies based

on social network services, chats, etc. proliferated and

avoided a feeling of isolation. This segues into

management implications: „making sense“ and

„giving purpose“ are managerial tasks, and a core

element of leadership (Kempster et al. 2011) and so

is maintaining connectivity. Making sure, that novice

workers are included into the formal and informal

communication network by all technical means, to

keep them connected, well-informed and as part of a

team, is crucial to avoid cutbacks in their personal

development.

As the sample size is too small to provide reliable

insights, further studies would be necessary to verify

the results. Expanding the research on employees

more advanced in their working careers could be

worth some exploration, as well as taking different

cultures and social millieus into account, who might

cope differently with this pandemic. As the situation

is exceptional, the stressor is episodic. Findings

gained within this rather extreme situation could give

valuable insights for home office communications in

the aftermath of the pandemic.

REFERENCES

Antonovsky, A. (1988): Unraveling the mystery of health.

How people manage stress and stay well. San

Francisco, London: Jossey-Bass Publ.

Antonovsky, A. (1991, 1979): Health, stress, and coping.

1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers (The

Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series).

Brauchli, R.; Schaufeli, W. B.; Jenny, G. J.; Füllemann, D.;

Bauer, G. F. (2013): Disentangling stability and change

in job resources, job demands, and employee well-

being — A three-wave study on the Job-Demands

Resources model. In: Journal of Vocational Behavior

83 (2), S. 117–129. DOI: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.03.003.

Dubey, A. D.; Tripathi, S. (2020): Analysing the

Sentiments towards Work-From-Home Experience

during COVID-19 Pandemic. In: jim 8 (1). DOI:

10.24840/2183-0606_008.001_0003.

Feldt, T. (1997): The role of sense of coherence in well-

being at work: Analysis of main and moderator effects.

In: Work & Stress 11 (2), S. 134–147. DOI: 10.1080/

02678379708256830.

Hobfoll, St. E. (2001): The Influence of Culture,

Community, and the Nested‐Self in the Stress Process:

Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. In:

Applied Psychology 50 (3), S. 337–421. DOI: 10.1111/

1464-0597.00062.

Hobfoll, St. E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M.

(2018): Conservation of Resources in the

Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and

Their Consequences. In: Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol.

Organ. Behav. 5 (1), S. 103–128. DOI: 10.1146/

annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640.

Jenny, G. J.; Bauer, G. F.; Vinje, H. F.; Vogt, K.; Torp,

Steffen (2017): The Handbook of Salutogenesis. The

Application of Salutogenesis to Work. Ed.. Mittelmark,

M. B.; Sagy, S.; Eriksson, M.; Bauer, G. F.; Pelikan, J.

M.; Lindström, B.; Espnes, G. A. Cham (CH).

Jessurun, J. H.; Weggeman, M. C. D. P.; Anthonio, G. G.;

Gelper, S. E. C. (2020): Theoretical Reflections on the

Underutilization of Employee Talents in the Workplace

and the Consequences. In: SAGE Open 10 (3),

215824402093870. DOI: 10.1177/2158244020938703.

Kempster, St.; Jackson, B.; Conroy, M. (2011): Leadership

as purpose: Exploring the role of purpose in leadership

practice. In: Leadership 7 (3), S. 317–334. DOI:

10.1177/1742715011407384.

Kompanje, E. J. O. (2018): Burnout, boreout and

compassion fatigue on the ICU: it is not about work

stress, but about lack of existential significance and

professional performance. In: Intensive care medicine

44 (5), S. 690–691. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-018-5083-2.

Özsungur, F. (2020a): The effects of boreout on stress,

depression, and anxiety in the workplace. In: bmij 8 (2),

S. 1391–1423. DOI: 10.15295/bmij.v8i2.1460.

Özsungur, F. (2020b): The Effects of Mobbing in the

Workplace on Service Innovation Performance: The

Mediating Role of Boreout. In: isarder 12 (1), S. 28–

42. DOI: 10.20491/isarder.2020.826.

Purwanto,.; Asbari, M.; Fahlevi, M.; Mufid, A.;

Agistiawati, E.; Cahyono, Y.; Suryani, P. (2020):

Impact of Work From Home (WFH) on Indonesian

Teachers Performance During the Covid-19 Pandemic

: An Exploratory Study. In: International Journal of

Advanced Science and Technology 29, S. 6235–6244.

Reijseger, G.; Schaufeli, W. B.; Peeters, M. C. W.; Taris,

T. W.; van Beek, I.; Ouweneel, E. (2013): Watching the

paint dry at work: psychometric examination of the

Dutch Boredom Scale. In: Anxiety, stress, and coping

26 (5), S. 508–525. DOI: 10.1080/10615806.2012.

720676.

Stressed by Boredom in Your Home Office? On „Boreout“ as a Side-effect of Involuntary Distant Digital Working Situations on Young

People at the Beginning of Their Career

563

Rothlin, P.; Werder, P.R. (2007): Diagnose Boreout.

Warum Unterforderung im Job krank macht. München:

Redline Verlag.

Spurk, D.; Straub, C. (2020): Flexible employment

relationships and careers in times of the COVID-19

pandemic. In: Journal of Vocational Behavior 119, S.

103435. DOI: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103435.

Stock, R. M. (2013): A hidden threat of innovativeness:

Service employee Boreout. In: AMA Winter Educators'

Conference Proceedings 24, 159ff.

Stock, R. M. (2015): Is Boreout a Threat to Frontline

Employees' Innovative Work Behavior? In: J Prod

Innov Manag 32 (4), S. 574–592. DOI:

10.1111/jpim.12239.

Stock, R. M. (2016): Understanding the relationship

between frontline employee boreout and customer

orientation. In: Journal of Business Research 69 (10),

S. 4259–4268. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.037.

APPENDIX

Questionnaire

Are you working from home due to the covid-19-

pandemic? (y/n)

How old are you? (<20,20-30, >30)

Which sex? (m/f/d)

Which industry?

How long do you work for your employer per week?

(>35h/week, 15-35 h/week, <15 h/week)

How long are you working for your employer? (<1 year,

1-4 years, > 4 years)

What is your current housing situation?

(single/family/other)

Children to care for? (y/n)

Did you have any experience working from home before

the pandemic? (y/n)

I have less contact with my colleagues/supervisors.

I feel left alone by my employer because of the home

office. / I no longer feel part of a team.

I receive no/less recognition for the work I do.

I do the same work slower in my home office.

I waste more of my working time on private matters than

before.

I have problems with organizing my own working day.

I have to do fewer tasks than I did before.

My assigned tasks have become easier.

I feel increasingly bored or underchallenged.

I currently have no more interest/opportunities to improve

my professional development.

I can easily contact my supervisors/colleagues if I need

help.

My work processes are restricted.

My creativity/work ethic has suffered from the isolation.

The longer the pandemic/home office goes on, the more

dissatisfied I become.

I am currently less willing to work overtime.

I am more dissatisfied with my job.

My employer prepared and planned the transition into

home office in a structured way.

My employer has ensured, that I can work from home by

providing software and hardware.

I have, by digital means, the feeling of being less isolated

than without.

I can imagine working more often in a home office in the

future.

I think that home offices will be used more often in the

future.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

564