Design of a Social Media Simulator as a Serious Game for a Media

Literacy Course in Japan

Marcos Sadao Maekawa

1

, Leandro Navarro Hundzinski

1

, Sena Chandrahera

1

,

Shota Tajima

2

, Shoko Nakai

2

, Yoko Miyazaki

2

and Keiko Okawa

1

1

Keio University Graduate School of Media Design, Yokohama, Japan

2

SmartNews Media Institute, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords: Media Literacy, Serious Games, Fake News, Social Media.

Abstract: This paper introduces the initial phase of the design process of a simulator about information sharing in social

media for educational settings. This online tool mimics real-world social media services and provides a playful

learning experience. Players evaluate online information, make decisions to share or not the information, and

as a result, gain or lose followers. Students can access other players’ statistics and analyze references such as

expert’s opinions to support their decision-making. Through this experience, students are expected to exercise

and reflect on their online social media behavior and become smart consumers and responsible creators of

online information. The preliminary findings reveal a glance of social media sharing behavior among

university students in Japan and clues for measuring the learning effects and the engagement for this sort of

practice. Results from this research are expected to contribute to digital media literacy education and serious

game design domains.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital media technologies are developing at

unprecedented speed, and the amount of information

available on the internet increases exponentially. At

the same time, it is hard for our skills to process and

evaluate to keep up with this enormous amount of

information that we are exposed to daily. One of the

indicators is the spread of fake news online.

It has been said that the spread of fake news is

related to age. The elderly shared nearly seven times

as many articles from fake news domain than younger

age groups (Guess et al., 2019). On the other hand,

young people’s ability to reason about information on

the internet is low (Wineburg et al., 2016).

We have never had this volume of information in

the reach of our fingertips, with just one touch of our

smartphones. Although the importance of media

literacy education is increasing, social media

behavior knowledge is not reflected enough in related

curriculums. Fact-check checklists have also been

criticized in regards to their usefulness on current

media literacy education settings. (Breakstone et al.,

2018; Mimizuka. 2020)

This paper presents the design process of a serious

game related to social media and fake news. It mimics

a social media service, and users are expected to

evaluate the information on posts and make decisions

about sharing or not a post, and if sharing, choose

between public or smaller groups. The main goal of

this tool is to trigger self-reflection on students

sharing behavior in social media. This game has been

designed as one component of a media literacy course

at a national university in Japan.

This serious game’s design process comprises

concept creation, development, and utilization of

games as engaging, playful and informative tools.

Understanding that the ability to consume online

information shapes one’s digital citizenship, the

purpose of this game is to allow students to reflect on

their behavior when dealing with information online.

This is expected to stimulate students to think of their

decision-making when consuming, creating, and

sharing content on social media. Moreover, it

stimulates students to engage in online participation.

This research aims to measure the outcomes of a

digital media course designed for university students

in Japan and contribute to the literature of media

literacy education in the digital era.

392

Maekawa, M., Hundzinski, L., Chandrahera, S., Tajima, S., Nakai, S., Miyazaki, Y. and Okawa, K.

Design of a Social Media Simulator as a Serious Game for a Media Literacy Course in Japan.

DOI: 10.5220/0010499903920399

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021) - Volume 1, pages 392-399

ISBN: 978-989-758-502-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Media Literacy and Media Literacy

Education

The spread of information and communication

technologies (ICT) made information accessible to

everyone with access to the Internet. This setting

deeply impacted the way we work, learn, socialize,

and made it easier for anyone to create media and

online content. Nowadays, we are all exposed to an

overwhelming amount of information online, making

it difficult to understand messages and distinguish

reliability.

The need to reconsider how we understand and

interact with information and media has been

reinforced by recent global events. Information

literacy and the media shape the way one makes

decisions and behaves toward social-political facts or

events such as a pandemic.

Considering the high connectedness context in the

current global society, media literacy has become a

core competence in educational frameworks around

the globe. Media literacy is “the ability to identify

different types of media and understand the messages

they’re sending” (Common Sense Media, n.d.). It is

directly related to topics such as 21st-century skills

and digital citizenship.

Education frameworks presented worldwide

show characteristics of strengthening the digital

context of media literacy and stimulating students to

creativity and expression. However, Japan still

struggles to incorporate digital media related topics

into the curriculum, despite the increasingly high

internet penetration among elementary (around

85.6%) and junior high school (95.1%) students,

including access from smartphones, tablets, and

personal computers (Cabinet Office, 2018).

As described by Maekawa et al. (2020), ”the goal

of the course developed with this research is to bring

the fundamental messages of media literacy

education in a different approach to media literacy

education practice at Japanese university

classrooms.” The course, as well as the components,

were designed based on the fundamental pillars of

learning competencies (knowledge, skills and

attitude) as described below (Maekawa et al., 2020):

Knowledge: Understand the dangers of

simplifying and labelling information;

Skill: Understand the key points to assess the

reliability of the information;

Attitude: Nurture responsible behaviour as a

digital citizen.

The course comprises three modules:

About Digital Media Literacy;

Information and News Literacy;

Behind the ‘Like it’ button.

Each module was designed to provide a blended-

learning experience with video, online interactive

activities, and group discussions.

The impact of the coronavirus in all levels of

education made 97% of Japanese universities offer all

courses online during the first half of the academic

year (Digital Knowledge, 2020), with many still

remote as of the first half of 2021. Because of that,

the course structure, as well as all its components,

were designed also for online, offline, or hybrid

learning environments.

2.2 Serious Games in the Context of

Fake News

Digital games are a part of daily life in Japan. In 2018,

the number of game players in Japan was estimated

to be 67.6 million (Newzoo, 2018), a number that

represents more than half of the entire country’s

population. The popularity of digital games is often

associated with engaging and meaningful

experiences.

In education, their potential for interactive

learning environments and collaborative learning

experiences have been seen in the shape of serious

games (Anastasiadis et al., 2018). The term serious

games can be defined as “any piece of software that

merges a non-entertaining purpose (serious) with a

video game structure” (Djaouti et al., 2011). Serious

games are also often seen used in conjunction with

other terms such as edutainment, digital game-based

learning, and immersive learning simulator (Alvarez

& Djaouti, 2011).

Schifter (2013) highlights the connection between

serious games and 21st-century classrooms with

games as external motivators, for drills, practices, and

other types of learning. Additionally, the games’

virtual environments can represent a safe

environment in which students can experience and

experiment with their skills and knowledge

(Anastasiadis et al., 2018). As such, games represent

a safe zone to try new approaches and ideas, without

real-world repercussions if they turn out to not be

good. Failure itself can be seen as a step conducive to

learning, which can help to initiate collaboration and

dialogue between peers and provide learners with

new insights (Anderson et al., 2018).

Serious games have been one of the ways utilized

to work with the problems caused by fake news.

Several games have been done utilizing different

Design of a Social Media Simulator as a Serious Game for a Media Literacy Course in Japan

393

approaches to bring awareness to the topic, such as:

“Bad News”, where you play the role of a fake news

producer and learn their techniques (Roozenbeek and

van der Linden, 2019); “Fake News Detective”, in

which you become a fact-checker in a hoax busting

organization (Junior, 2020); and “LAMBOOZLED!”,

a competitive deck-building card game to enhance

news literacy skills (Chang et al., 2020). Each with

their own approach, those games were utilized as

ways to work with misinformation and news literacy.

Another game called “Factitious” utilizes data

collection mechanisms to allow assessment of factors

such as patterns in understanding news literacy and

play experience (Grace and Hone, 2019).

In the next section, we will introduce the game

Brain Company, designed in the Graduate School of

Media Design, Keio University as a master’s project.

2.3 Brain Company

Brain Company (Mengyun, 2019) is a card game that

aims to bring awareness about the dangers of fake

news. It was designed around the concept that sharing

fake news or not sharing reliable news can have real-

life impacts.

Players score points by sharing reliable news and

blocking fake news. If they share fake news or block

trustworthy news sources, they lose points instead.

Each news piece is associated with reference cards,

which aim to give other perspectives on the

information and aid the player in making a decision.

The reference cards are designed to simulate a variety

of sources, from reliable news sources to social

media. It is up for the players to decide which of those

references are to be considered trustworthy and help

them to identify if the news is fake or not. The

objective of associating each news with other sources

is to show the importance of researching and filtering

information before sharing online, as well as

considering the sources where each piece of news or

associated information comes from.

Players have a time limit to make their decisions

on sharing or blocking for 10 different news cards.

The playing part is a single-player, but the idea of

Brain Company is to run multiple single-player

sessions in parallel at once. This way, after the

individual sessions are over, players can compare

their scores and results with each other.

One unique aspect of Brain Company to other

games about fake news is that it exemplifies to

players how social, economic and environmental

problems can be linked to their choices on

contributing or not to misinformation. The impact can

be seen immediately after the play session, giving

players the possibility of establishing a causal

relationship with their decisions on sharing or

blocking pieces of news. Some of those scenarios are

based on real fake news cases and others are fictional.

When comparing their results, players can engage in

conversations on how each of their scenarios might

differ, raising many points for discussion.

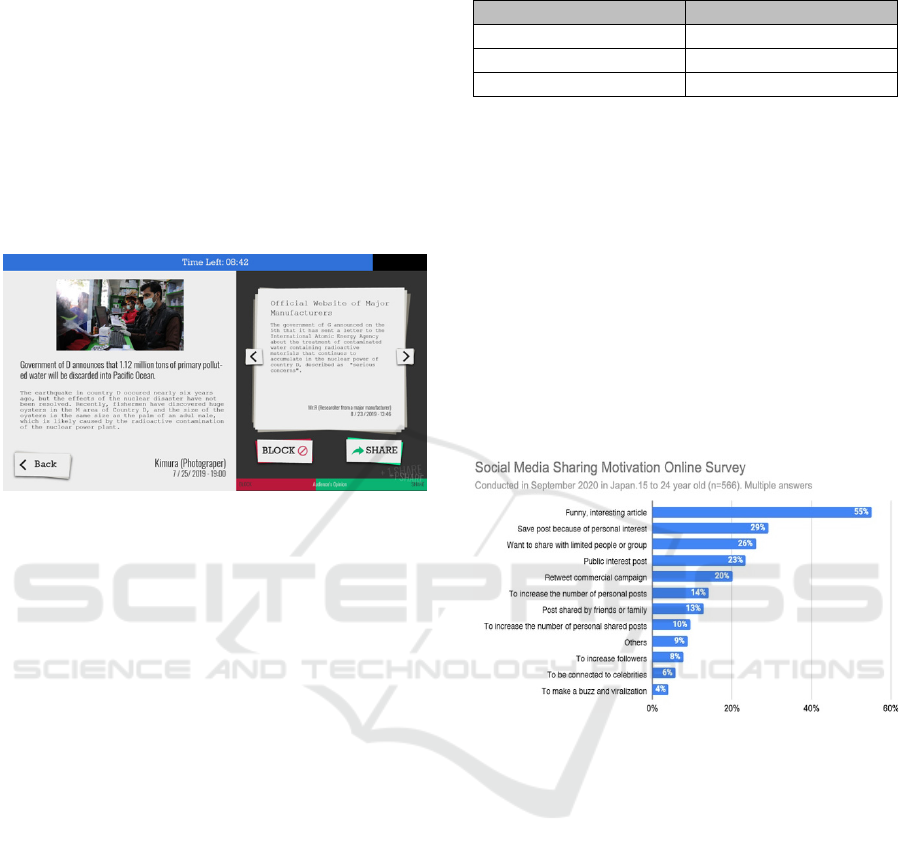

The following image (Figure 1) shows an example

of fake news included in the game, as well as the

impact caused in society by the massive sharing or

blocking of this news piece.

Figure 1: Results from sharing or blocking news in Brain

Company.

In the case above, the information stating that the

tuna died because of flash photography in the

aquarium was fake news. So, if players share this

information, the consequence is that a junior high

school student who visited the aquarium and took

photos with flash gets bullied by his classmates (and

in this case, players lose points for sharing fake

news). On the other hand, by blocking the fake news,

players score points and the aquarium is not affected

by misleading information, keeping its popularity as

a visiting spot.

Brain Company's goal was to show those

scenarios to players and allow them to reflect on the

consequence of their actions online. Comparing

before and after they play the game, test participants

shifted their view towards the impact they have when

they share news to be more cautious on the

information they share, as well as on researching

several sources to assess the reliability of news.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

394

3 DESIGN CONCEPT

The game designed in this research is part of a higher

education course on media literacy. This course

includes time in the lecture for students to learn how

to handle the online information around them through

blended learning activities such as watching videos,

classroom discussions, and the serious game

described in this paper. To better understand the

context, we describe the course core concept and how

it impacts the game design process.

3.1 Media Literacy Course Concept

The core structure of the course (Maekawa et al.,

2020) is also adopted in the game design, as described

below.

Knowledge: Understand the dangers of

simplifying and labelling information.

There is a lot of information that cannot be

classified as completely correct or completely wrong.

In fact, there are grey areas in determining accuracy

in fact-checking. The value of information varies with

context, and even experts may disagree about its

reliability.

Skill: Understand the key points to assess the

reliability of the information

Meta information like author and publish date is

often useful for evaluation. Figure out what can be

used as meta-information and what to pay attention

to. In some cases, it is useful to estimate the intent of

the publisher. Various reasons exist for publishing

fake news, including revenue, propaganda, desire for

approval, and misunderstanding.

Attitude: Nurture responsible behaviour as a

digital citizen

Proactive sharing of valuable information can lead

to a wealth of information space, community

development, and solutions to social problems. On

the other hand, even non-malicious sharing can foster

misunderstanding and discrimination. The term

"information" is not limited to articles in the

commercial media, but also includes UGC, as

represented by social networks as well as corporate

and government announcements and data.

3.2 Game Concept

Based on knowledge, skill, and attitude, the game

aims to engage players through making decisions of

sharing information on social media. The first action

that players make is to evaluate information in a

context that mimics real-world services. The user

interface takes an SNS-like look by displaying card-

type information and a timeline styled layout. The

game also presents real articles and posts, so players

can use them as references to base their decision

making.

The second action players take is to analyse

experts’ opinions as part of how to read and

understand information. In a real-life context, readers

are influenced by opinion leaders and key persons

related to a determined subject. It is also said that

what others in their social circle do can influence

one’s opinion.

3.3 Game Experience

The original card game is a single-player game.

However, it is meant to be played with more players

simultaneously, as the results can be compared

through a ranking system. In the setting of a

workshop, comparing results between players can

create an environment conducive for discussions and

deeper analysis to take place.

As such, the new game experience based on Brain

Company can be seen in two main parts:

The first part is the individual play session, in

which each player reads different news and

references, deciding to share or to block the

information. Each player's decision process is

based on their interpretation of news and sources,

related to their assessment of the reliability of

each piece of information;

The second part is the discussion session, in which

players can compare their results and discuss the

impacts of the news they shared and blocked, as

well as discuss the importance of responsible

behaviour as a digital citizen. In this part, players

can see the overall session results, how players

answered, and what type of scenario their choices

created. The statistics of other players' choices, as

well as the answers of specialists in the topic of

the news are shown, adding extra elements for

discussion.

3.4 Initial Digitization

To approach the digitization of the concept originated

from the card game Brain Company, the first step was

to digitize the original game. Initially, we converted

the original game experience as is, without

adjustments. However, the original version was not

designed with specific course modules in mind.

Consequently, missing features and opportunities for

changing the design were detected.

Design of a Social Media Simulator as a Serious Game for a Media Literacy Course in Japan

395

The goal in this first step was building the same

experience designed in the original game but in a

digital medium. Some advantages from having the

game in a digital version includes having pictures for

each news to mimic a real article, providing a timer,

adding soundtrack, saving session results, and linking

different sessions with several participants in the

same group through a code system.

The following picture (Figure 2) shows how each

news is presented to the players, with

blocking/sharing features, reference cards on the right

side and meta-information.

Figure 2: Initial digitization of Brain Company.

3.5 Refinement based on the Initial

Digitization

Initially, the development platform changed from

Game Maker Studio 2 (utilized on the digitization

step) to a JavaScript implementation. This change

was based on intended features and scalability. The

version created during the digitization step served as

a benchmark for the mechanics from Brain Company.

From this point, we decided to create a new game

from scratch, based on the design aspects of Brain

Company. The main change is on how the objective

of the game is presented to players. In Brain

Company, players aimed to score higher to compete

with other players and perform well.

In this new version, players take influencers' role,

and their final score is based on the number of

followers they can obtain. To increase their number

of followers, they must share reliable news and block

fake news. If they do the opposite, the number of

followers will decrease.

According to results from a preliminary online

survey, this design decision focuses on the sharing

behavior in social media among youth in Japan. We

built an online version of the game as a mock-up. We

listed up 20 posts (including real and fake news) and

asked respondents to make decisions on sharing

(public share, limited share, and not to share) and

indicate the reliability of that post.

Table 1: Results of sharing behavior.

RESULTS Percentage (n=566)

Shared (public) 10.2

Shared (private) 10.0

Did not share 79.8

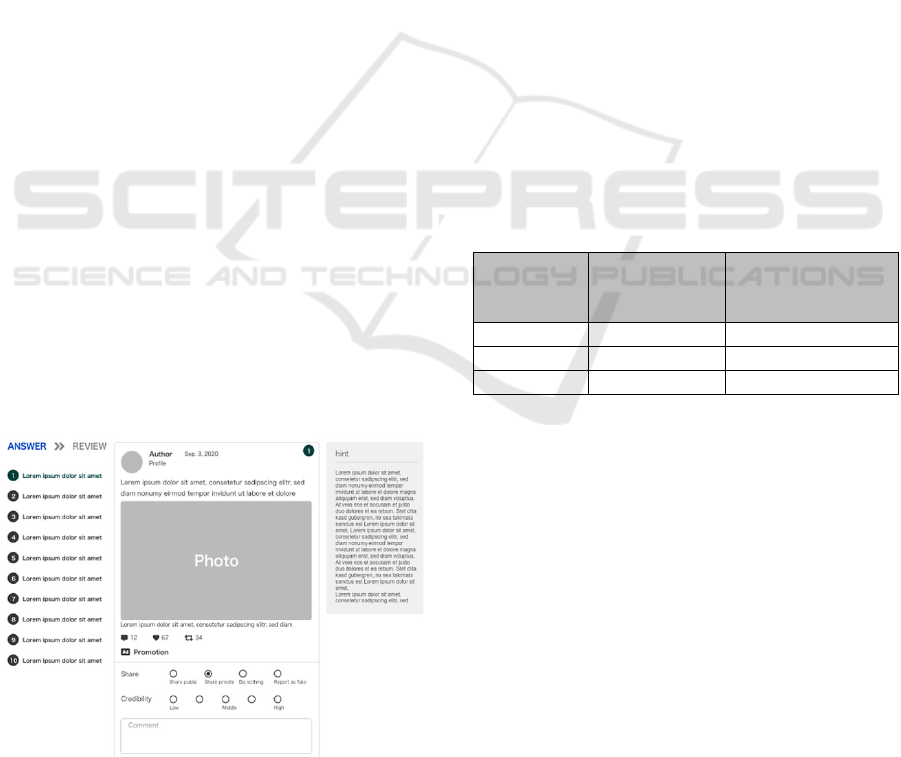

There were 566 valid responses, and the age range

varies from 15 to 24 years old. The results revealed

that 79.8% of respondents did not share posts (Table

1). When asked about why they shared a post, 55%

declared that it was because the post content was 面

白い (omoshiroi) that stands for interesting, funny,

entertaining (Figure 3). Regarding criteria to evaluate

the post's credibility rate, 61.48% mentioned the

citation source, followed by 59.72% who mentioned

the author of the post. The number of likes and shares

also influences the decision (26.33% and 20.85%,

respectively). Based on these results, we decided to

add an incentive component to stimulate users to

share more posts.

Figure 3: Reasons and motivation to share posts.

The results of this preliminary survey shaped the

design refinements of this version. The following list

details features added on the design of the new game,

many of them aiming at engaging players by making

the game more realistic or containing interactions that

mimic social media usage:

Existing news: all news shown to players are

examples of real news or fake news. In Brain

Company, some of the information was based on

real cases, but not necessarily the same as the

original source. From now, all news shown is

based on real (or 'real gale's) sources;

Statistics: players can see in real-time the answers

from other players. This can influence how

information is perceived based on the pressure of

other players. In the discussion step, comparing

players' answers and utilizing captured data to

generate relevant statistics on answering patterns

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

396

and information perception can be a resource for

discussion and learning;

Specialists perspective: players can see

specialists' opinions on the credibility of each of

the news they blocked or shared. This can be used

as a material for the discussion session in the

second part of the game, showing different

perspectives on how to assess information

reliability;

Algorithm-based scoring system: the scoring

system for the new game is based on relevance

algorithms utilized in social media services. If a

specific news is shared by the overwhelming

majority of players, then the quantity of followers

the players can get or lose is also higher,

increasing the weight of their decision. This aims

to mimic how trends tend to be highlighted on

content websites, with everyone talking about the

same subject. Many times, when a new trend

happens, many content producers / influencers

also create content on the same topic, as trendy

can mean increased revenue or exposure. Because

of how information tends to be replicated

thousands of times during trends, the impact can

also be greater. After the game session, players

will be able to see how many followers each

player obtained.

Some of the features are still a work-in-progress

in terms of implementation, but already defined as

part of the new design. The changes in design

presented in the next chapter aim to increase the

engagement of the players and make the game more

connected to real-life internet usage.

3.6 Incentive Design and User

Engagement

Figure 4: New game implementation and interface.

The new design aims to be more realistic and add

more layers when assessing the credibility of

information. To achieve a more relatable and

believable setting, a new visual style was developed

to mimic a social media interface. This change also

relates to the change that players now play the role of

an influencer with the objective of having more

followers. The following picture (Figure 4) is an

example of the new user interface added to the game.

The setting of being an influencer in online media

is chosen to create a more relatable setting for players.

Students participating in the game sessions during the

media literacy course are university freshmen and, in

general, close to the reality of social media usage.

Being an influencer also means that they would be

held more accountable towards what they share on

social media.

In this phase of the design, the tool introduces

components that will help understand social media

sharing behavior. The first one allows players to define

the range (public or private) when sharing a post. The

decisions taken at this point will impact the number of

followers they will get or lose. The algorithm used for

the following count (Table 2) allows those who share

posts with no fake information, will get more

followers. On the other hand, if they share fake

information, they lose followers.

Table 2: Algorithm for followers count.

SHARING Not Fake

News post

(x=followers)

Fake News post

(x=followers)

Public x + 3x x

–

x/2

Private x + 2x x

–

x/4

N

o sharin

g

N

o chan

g

e

N

o chan

g

e

The second component is related to information

credibility. Players can rate how credible they believe

each news to be and an open space for commenting

on the reasons they decide to share or block the news.

This information is not meant to impact the final score

of the game as much, but to generate data that can

enrich the discussion session after the play sessions.

From the perspective of the player, it aims to evoke

further consideration before making a final decision

during the game. In some cases, information cannot

be defined as totally fake or true. There might be

some truth in a piece of fake news, when looked at

from different perspectives or different contexts. This

creates a dilemma in which people can get confused

when assessing information reliability. Evaluating

how certain a player is in their choice of sharing or

blocking a certain news can generate meaningful data

that can be studied further.

Design of a Social Media Simulator as a Serious Game for a Media Literacy Course in Japan

397

The final prototype in this phase was composed of

10 posts extracted from real social media and

included real news, fake news, advertising (or

promotion), and opinions. Each participant starts with

100 followers. The players are encouraged not only to

increase the number of followers, but also to play it

as close as to an actual situation in social media in

their daily lives.

4 ITERATIONS AND ANALYSIS

Two different iterations were conducted over the

prototype described in 3.7 as of this paper’s

submission date (January 2021). The following

subchapters describe both iterations and present

preliminary conclusions for this phase of the research.

The first iteration was conducted in mid-

November of 2020, in a hybrid lecture environment

with 13 freshmen students (onsite and online). They

had a brief explanation about the serious game and

how it works. The gameplay was set for 30 minutes

and followed by class discussion. After the end of the

activity, they answered an online questionnaire about

their impressions.

The questionnaire was built to understand sharing

behavior in social media, the criteria they use to make

their decision to share or not a post and what was their

impression after using the simulator.

The results revealed that eight among 13 students

mentioned the “verified account” mark was the main

factor in evaluating the posts’ credibility. Besides,

most students (12 among 13) mentioned the account

holder as the primary valuation criteria. On the other

hand, students are likely to mention services and

platforms and data aggregators such as Yahoo!News,

LINE News, SmartNews, Twitter and YouTube when

asked about the original media source.

According to the students’ impressions

comments, it is very likely that the activity can trigger

reflection on users’ online behavior and even made

them change their perception towards evaluation

criteria. “Until now, I used to rely on verified account

marks to evaluate online information, but I felt that

even a verified account could be sharing a piece of

questionable information. I need to be more careful

from now on,” said one of the students. “This activity

made me think and reflect about my criteria to

evaluate information online, and it made me realize

that my evaluation criteria were not clear.”

A second iteration was held in late December

2020 in an online classroom setting with 23 students.

The main finding came from the feedback from

stakeholders. We interviewed the lecturer who

conducted both iterations in his sections and with the

media literacy course coordinator. The lecturer

mentioned that students were engaged in the activity.

Discussions started with the spontaneous comparison

of the number of followers at the end of the game,

indicating that the gamification component of the

experience likely contribute to engage and motivation

for sharing. The coordinator said there is a great

potential in this serious game since the ultimate goal

is not about winning or losing; there is no right or

wrong. The final result reflects the real situation and

may help students to understand their online

behavior.

Both made suggestions of features such as the

visualization of the game progress. They also

emphasized that the initial briefing should not be too

long or too detailed because it may influence

students’ mindset in a competitive direction.

5 FUTURE WORKS

The first run of the game in the actual course setting

is scheduled to start in Japan's new academic year,

starting in April 2021. The team will then refine its

design to match the media literacy course's academic

needs according to the feedback and findings from

iterations.

One of the main improvements is related to the

lecturer's feedback, such as an interface to share real-

time progress of all students and final results and the

customization of real content. These factors may

define and give more flexibility to the way lecturers

conduct the activity and the discussion afterward.

After the first course run, we expect to explore the

data collected and feedback to make a more in-depth

analysis of the first version of this serious game and

evaluate the impacts of this approach in a real

educational setting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This paper and the research behind it would not have

been possible without the exceptional support of

Professor Tomohiro Inagaki and Associate Professor

Atsushi Hikita from Hiroshima University,

Smartnews Research Institute and all other

institutions involved.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

398

REFERENCES

Alvarez, J. & Djaouti, D. (2011). An introduction to Serious

game - Definitions and concepts. Serious Games &

Simulation for Risks Management. 11(1), 11-15.

Anastasiadis, T., Lampropoulos, G. & Siakas, K. (2018).

Digital Game-based Learning and Serious Games in

Education. International Journal of Advances in

Scientific Research and Engineering, 4(12), 139–144.

https://doi.org/10.31695/IJASRE.2018.33016

Anderson, C. G., Jen, D., Vishesh K., Berland, M. &

Steinkuehler, C. (2018). Failing up: How Failure in a

Game Environment Promotes Learning through

Discourse. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 30, 135–144.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.03.002

Breakstone, J., McGrew, S., Smith, M., Ortega, T., &

Wineburg, S. (2018). Why we need a new approach to

teaching digital literacy. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(6), 27–

32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721718762419

Cabinet Office. (2019).

平成

30

年度

青少年のインター

ネット利用環境実態調査報告

. (Fact-finding Survey

on Internet Usage Environment among Youth - 2018)

https://www8.cao.go.jp/youth/youth-harm/chousa/h30/

net-jittai/pdf-index.html

Chang, Y. K., Literat, I., Price, C., Eisman, J. I., Chapman,

A., Gardner, J. & Truss, A. News Literacy Education in

a Polarized Political Climate: How Games Can Teach

Youth to Spot Misinformation. Harvard Kennedy

School Misinformation Review, 1(3), 2020.

Common Sense Media. (n.d.). What is media literacy, and

why is it important? https://www.commonsensemedia.

org/news-and-media-literacy/what-is-media-literacy-

and-why-is-it-important

Digital Knowledge. (2020, July 16).

大学におけるオンラ

イン授業の緊急導入に関する調査報告書

. (Survey

Report on Emergency Implementation of Online

Lectures in Higher Education). https://www.digital-

knowledge.co.jp/archives/22823

Djaouti, D., Alvarez, J. & Jessel, J. (2011). Classifying

Serious Games: The G/P/S Model. IRIT – University of

Toulouse. http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60960-495-

0.ch006

Grace, L. and Hone, B. (2019). Factitious: Large Scale

Computer Game to Fight Fake News and Improve

News Literacy. CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems Extended Abstracts (CHI’19

Extended Abstracts). https://doi.org/10.1145/3290607.

3299046

Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you

think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news

dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1),

eaau4586. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4586

Junior, R. B. (2020). The Fake News Detective: A Game to

Learn Busting Fake News as Fact Checkers using

Pedagogy for Critical Thinking. Georgia Institute of

Technology.

Maekawa, M., Hundzinski, L., Chandrahera, S. & Tajima,

S. (2020). Design of a Serious Game about Fake News

for a Media Literacy Course. AXIES 2020 -

大学

ICT

推進協議会

.

Mengyun, L. (2019). Design of a Party Game to Raise

Awareness of Fake News. Master’s Thesis. Keio

University Graduate School of Media Design.

Mimizuka, K. (2020). Rethinking Media Literacy in The

Age of Online Disinformation: A Review of Global

Discourse and Challenges.

社会情報学

(Journal of

Socio-Informatics, 8(3), 2020.

Newzoo. (2018, August 1). Japan Games Market 2018.

https://newzoo.com/insights/infographics/japan-

games-market-2018/

Schifter, C. C. (2013). Games in learning, design, and

motivation. Handbook on innovations in learning, 1Ͷͻ-

16Ͷ.

Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S. (2019). Fake news game

confers psychological resistance against online

misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(12).

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0279-9

Wineburg, Sam and McGrew, Sarah and Breakstone, Joel

and Ortega, Teresa. (2016). Evaluating Information:

The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning. Stanford

Digital Repository. http://purl.stanford.edu/

fv751yt5934

Design of a Social Media Simulator as a Serious Game for a Media Literacy Course in Japan

399