Human-centred Design of Self-management Health Systems with and for

Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines

Ine D’Haeseleer

a

, Karsten Gielis

b

and Vero Vanden Abeele

c

KU Leuven, e-Media Research Lab, Belgium

Keywords:

Human-centred Design Process, Older Adults, Challenges, Health, Self-management, Recommendations.

Abstract:

Human-centred design approaches that involve older adults are becoming more and more commonplace in the

development of digital systems to support self-management of health and well-being, ultimately contributing

to ageing in place. In order to understand and design effective solutions, it is important to involve older

adults from the beginning and throughout the iterative development process. However, conducting studies

with this target population presents challenges and therefore requires specific adaptations. In this study, we

reflect on the different human-centred methods, e.g., focus group discussions, interviews, and user-tests, that

were conducted with older adults. In total, 81 participants (aged 65 to 97) were involved in a four-year

human-centred design process. On the basis of a thematic analysis, we reflect on the different methodological

intricacies encountered and identify four themes: ‘a life course marked by grand experiences’, ‘a discomfort

with unknown digital technologies’, ‘impact of age-related impairments’, and ‘relatedness as core to research

participation’. Finally, insights and practical guidelines are formulated to help future researchers undertake

more effective and useful human-centred study designs with older adults.

1 INTRODUCTION

Increasingly, older adults are involved in the design

and development of digital systems to manage their

health and well-being (Lindsay et al., 2012; Xie et al.,

2012; Davidson and Jensen, 2013b; Mehrotra et al.,

2016; Volkmann et al., 2016; Sengpiel et al., 2019;

Cornet et al., 2020; Czaja et al., 2019). A scoping

review

1

of studies with older adults in the ACM Dig-

ital Library (Association for Computing Machinery,

2021) revealed 1288 studies, a number that has been

increasing exponentially during the last decade. In its

slipstream, researchers have directed their attention

to the intricacies of involving older adults in the de-

sign of interactive technologies, specifically to man-

age their health (Lindsay et al., 2012; Chaudhry et al.,

2016; Sengpiel et al., 2019; Cornet et al., 2020). Most

recently, Sengpiel et al. (2019) introduced HCD+ as

‘human-centred design for aging’, a specific approach

to address how HCD-methods need to be adapted in

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5455-3581

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7660-8544

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3031-9579

1

Query: ((“user-centred design”) OR (“participatory

design”) OR (“human-centred design”)) AND ((“older

adults”) OR (“elderly”)) AND (“health”))

order to involve older adults as experts of their own

age group. Hence, the body of studies on how to adapt

an HCD process to older adults is continually grow-

ing.

Nevertheless, to date, recommendations and

guidelines on including older adults in the design of

health systems are still few and fragmented. Most of-

ten, research studies focus on the outcomes of HCD

methods, e.g., the majority of studies focus first and

foremost on the product, i.e., the designed system

or service, with the lessons learned on working with

older adults as an afterthought to be discussed (Xie

et al., 2012; Davidson and Jensen, 2013b; Mehrotra

et al., 2016; Volkmann et al., 2016). Notwithstanding

the value of such studies, they may be limited in their

reflection on the HCD methodology. Moreover, most

studies are not specifically geared towards interactive

technologies supporting self-management of health,

but towards ICT in general.

Self-Management Health Systems (SMHS) have

gained increasing interest from researchers; in partic-

ular to empower older users and contribute ageing-

in-place (Sintonen and Immonen, 2013; Heart and

Kalderon, 2013; Peek et al., 2016; Kononova et al.,

2019; D’Haeseleer et al., 2019). Yet, SMHS present

specific challenges as they may relate to sensitive is-

90

D’Haeseleer, I., Gielis, K. and Abeele, V.

Human-centred Design of Self-management Health Systems with and for Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines.

DOI: 10.5220/0010529100900102

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2021), pages 90-102

ISBN: 978-989-758-506-7

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

sues, and bring a limited biomedical focus on age-

related decline (Vines et al., 2015; Nunes et al., 2015).

The aim of this study is to contribute to the grow-

ing body of HCD+ in health, by presenting a thematic

analysis of methodological observations and reflec-

tions on an HCD process of an SMHS, that encom-

passed all phases (inspiration, ideation, implementa-

tion, and evaluation), involving 81 older adults with

ages ranging from 65 to 97 (median=83) over a pe-

riod of four years. In this paper, we present this

analysis and provide lessons learned, transformed into

practical guidelines, to help future researchers set up

more effective and useful study designs for conduct-

ing HCD processes with older adults.

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

WORK

There is an increasing interest in executing HCD pro-

cesses for and with older adults and health systems

in particular. In the paragraphs below, we first dis-

cuss the different understandings of human-centered

design. Next we present studies on that involved older

adults in the design process. We end this section with

existing guidelines related to older adults, HCD, and

health.

2.1 Involving End-users in the Design

Process

Different methodological approaches have been pro-

moted to involve older adults in the design and evalu-

ation of interactive, digital systems, labelled among

others as User-Centred Design (UCD), Human-

Centred Design (HCD) or Participatory Design (PD).

The term UCD was promoted already in Gould and

Lewis’ (1985) seminal paper on ‘Designing for Us-

ability’. In this work, the authors present three pil-

lars for any UCD process: involving users early, us-

ing empirical measurement, and conducting an itera-

tive design. In 1999, the ISO standard on HCD was

launched, embodying the aforementioned pillars of a

UCD process, and further detailing how to involve

end-users in the different phases. Moreover, con-

ceptually the ISO-standard also emphasises the hu-

man rather than the user, thus “putting people before

machines” (Cooley, 1996; Brown et al., 2008; ISO,

2019).

In parallel to UCD and HCD processes, also PD

grew in importance, originating from the premise that

those who ultimately have to use or are affected by

the implementation of technology should have a criti-

cal role in their design (Muller and Kuhn, 1993). PD

is, above all, an ideology that aims for empowerment

of end-users, and considers any design process as a

dialectic process between the different stakeholders

(end-user, designer, project owner, etc.) that serves

to unearth conflicting values. Co-design is also fre-

quently used to point to practices where end-users

are invited to collaboratively design and prototype

(Sanders, 2002). This term is often used interchange-

ably with PD, although with the term co-design, the

emphasis shifts to the actual methods used and less

the ideology.

Despite the different origins and delineations, re-

searchers often hold an idiosyncratic interpretation of

the methodological approaches, and apply them in a

lenient manner. As a consequence, in practice, the

boundaries between UCD, HCD, PD, and co-design

are fuzzy, yet they are united in the central premise

that stakeholders, i.e., here older adults, need to be

involved in the design.

2.2 Involving Older Adults in the

Design Process

Involving older adults is a recurrent topic in Human-

Computer Interaction (HCI), e.g., (Czaja et al., 2019;

Lindsay et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2012; Davidson

and Jensen, 2013b; Sengpiel et al., 2019; Cor-

net et al., 2020). Most recently, Sengpiel et al.

(2019) introduced HCD+, or ‘human-centered de-

sign for ageing’, a new approach that specifically

“considers older adults’ requirements and abilities

throughout the development process, adapting estab-

lished HCD-methods to accommodate the participa-

tion of older adults as experts for their own age

group”. The authors applied their HCD+ approach

to a project that centred on “Historytelling”, including

183 older adults (mean age=66.6, SD=7.5) within dif-

ferent HCD+ activities, i.e., focus group discussions,

workshops, interviews, and evaluations. From this,

the following guidelines were derived: ‘engage with

group leaders’, ‘emphasise reciprocity when recruit-

ing’, ‘plan for social engagement’, ‘overestimate the

scheduled time’, ‘accommodate participants’ wishes’,

‘establish (low-technology) fall-backs’, and ‘use ab-

stract descriptions of technology’ (Sengpiel et al.,

2019).

Notwithstanding, Sengpiel and colleagues were

the first to coin the term HCD+ (Volkmann et al.,

2016; Sengpiel et al., 2019), they are not the first to

propose frameworks or guidelines on how to include

older adults in the design process. Already in 2012,

Lindsay et al. (2012) investigated how to engage older

adults in PD processes. They identified in particular

Human-centred Design of Self-management Health Systems with and for Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines

91

four challenges: ‘maintaining focus and structure in

meetings’, ‘representing and acting on issues’, ‘envi-

sioning intangible concepts’, and ‘designing for non-

tasks’ (Lindsay et al., 2012). To address these chal-

lenges they suggested a new approach (termed OA-

SIS) that highlights the importance of ‘stakeholder

identification and recruitment’, ‘the usage of video

prompts’ to illustrate usage scenarios, followed by

‘exploratory meetings’ to explore the problem do-

main, and finally ‘low-fidelity prototyping sessions’,

here to be understood as co-design sessions to gener-

ate further requirements.

Two recent systematic literature reviews (Duque

et al., 2019; Amaro et al., 2020) further corrobo-

rate the growing number of studies on involving older

adults in the design process; one on user-centred and

participatory design with older adults (Duque et al.,

2019), and one on engaging older adults in participa-

tory and intergenerational design teams (Amaro et al.,

2020). Their findings echo the same considerations

stated above, highlighting the need for a better un-

derstanding and proper integration of older adults in

UCD and PD in general. Additionally, in their future

work, Duque et al. (2019) articulate the need for more

research in the domain of health self-medication.

2.3 Human-centred Design of Health

Technology

Given the prevalence of studies on older adults and

health technology, myriad studies have also applied

HCD processes in the domain of self-management of

health and well-being by older adults. In this section,

we limit ourselves to recent studies of SMHS that pro-

vide a detailed account of the process and method-

ological challenges, followed by recommendations.

The aforementioned OASIS process was also ap-

plied in the context of mobile health applications with

18 older adults (Davidson and Jensen, 2013b). Based

on their findings, researchers suggested additional

considerations. In particular, ‘short design sessions’,

‘allow for socialising among participants’, ‘encour-

age active participation’ by calling upon specific peo-

ple, and ‘finding a balance between input from re-

searchers and participants’ were added during the dif-

ferent workshops.

Chaudhry et al. (2016) conducted a UCD with

older adults and caregivers (mean age=66, SD=9.2)

to design and evaluate a tablet-application to promote

successful ageing called seniorHealth. Focus group

discussions, interviews, and pilot studies were con-

ducted. Both methodological and ethical challenges

encountered during the design and deployment of the

application, e.g., ‘difficulties in forming a design’,

‘high learning curve’ for using technology, and the

‘need for social support’.

Martin-Hammond et al. (2018) conducted a PD

involving 18 older adults (mean age=76, SD=8.25)

including seven phases: background survey, app cri-

tique, team presentation, current health info man-

agement practices, co-design, another team presenta-

tion, and a Q&A. Based on their findings, challenges

were encountered and strategies were shared: ‘enlist-

ing allies in recruitment’, ‘incorporating a design cri-

tique’, ‘use of common vocabularies’, ‘accommodat-

ing schedules and adapting the protocol’, and ‘partic-

ipation in creating tangible artefacts’.

Harrington et al. (2018) used co-design sessions

to design fitness apps with 25 older adults (mean

age=72.1, SD=4.25). These authors highlight in par-

ticular the differences between those familiar with

and those new to the technology, resulting in a tension

between the need to familiarise a participant with a

technology and the importance of not biasing a partic-

ipant through technology exposure. The authors also

found that continued use of the assigned application

led to more robust and detailed feedback in design

sessions, suggesting that long-term prior use of sam-

ple technologies is an important prerequisite to ideat-

ing useful features for new health technology.

Finally, a recent study on mobile health appli-

cations for older adults with heart failure indicated

the importance of tailoring the UCD process to older

adults (Cornet et al., 2020). Based on the authors’ ex-

periences, 12 practical challenges were enumerated,

including, but not limited to, ‘managing UCD logis-

tics’, ‘determining timing and level of stakeholder

involvement’, ‘overcoming designers’ assumptions’,

and ‘adapting methods to end-users’. In addition, au-

thors provided suggestions on how to overcome these

challenges.

Table 1 summarises the different challenges and

recommendations provided by the aforementioned

studies. While informative, certain guidelines seem

to conflict, e.g., overestimating time (Duh et al., 2016;

Sengpiel et al., 2019) versus to keeping sessions short

(Davidson and Jensen, 2013a), or providing tangi-

ble examples (Lindsay et al., 2012; Martin-Hammond

et al., 2018) versus using abstract descriptions of tech-

nology (Sengpiel et al., 2019). Moreover, most guide-

lines were not formulated in the context of SMHS.

Finally, not all studies report on the age of the partic-

ipants that were included, e.g., (Lindsay et al., 2012;

Cornet et al., 2020). Others reported findings where

mean ages typically varied from 65 to 75 years old

(Chaudhry et al., 2016; Harrington et al., 2018; Seng-

piel et al., 2019). Therefore, in this research study we

set out to perform a rigorous analysis of methodolog-

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

92

Table 1: A chronological overview of the studies encountered in the related work section, summarising the research study

methodology along with the challenges and guidelines.

Research Study Participants Study Design Challenges & Guidelines

Engaging Older People using

Participatory Design (Lindsay

et al., 2012)

[not specified] PD OASIS approach: identification

and recruitment of stakeholders,

video prompt creation, exploratory

meetings, low fidelity prototyping

maintaining focus and structure in meetings (challenge), represent-

ing and acting on issues (challenge), envisioning intangible concepts

(challenge), designing for non-tasks (challenge), stakeholder identifica-

tion and recruitment (guideline), the usage of video prompts (guide-

line), exploratory meetings (guideline), low-fidelity prototyping ses-

sions (guideline)

Participatory Design with

Older Adults: An Analysis

of Creativity in the Design of

Mobile Healthcare Applications

(Davidson and Jensen, 2013a)

18 older adults aged

65 to 88 years

OASIS approach: identification and

recruitment of stakeholders, video

prompt creation, exploratory meet-

ings, low fidelity prototyping

Keep design sessions short: trade-off between design quick and effi-

ciently, and lower novelty score (guideline), allow for informal socialis-

ing: informal socialising prior to design sessions (guideline), encourage

participation: call on specific people (guideline), balancing researcher

and participant input: allow questions but encourage to work together

(guideline)

Developing Health Technolo-

gies for Older Adults: Method-

ological and Ethical Considera-

tions (Chaudhry et al., 2016)

40 older adults

(M=66, SD=9.2)

UCD with focus group discussions,

interviews, and pilot studies

design: limited technology-based suggestions as participants were

novices (challenge), learning curve: difficulties on learning using tech-

nology (challenge), social support: interpersonal interactions between

participants (challenge), knowing the user: busy lives, distracted during

training, curious and eager to learn (challenge), sustainability: support

network after the study ended (ethical reflection)

Designing Health and Fitness

Apps with Older Adults: Exam-

ining the Value of Experience-

Based Co-Design (Harrington

et al., 2018)

25 older adults

aged 65 to 80 years

(M=72.1, SD=4.25)

co-design in seven sessions and

semi-longitudinal deployment

leverage pre-study experience (guideline), facilitate longer-term tech-

nology use (guideline), use varied materials and instruments for co-

creation engagement (guideline), establish a collaborative and com-

fortable approach to reviewing brainstormed ideas (guideline), stratify

group participants by experience levels (guideline)

Engaging Older Adults in

the Participatory Design of

Intelligent Health Search Tools

(Martin-Hammond et al., 2018)

18 older adults

aged 61 to 93 years

(M=76, SD=8.25)

PD with background surveys, app

critique, team presentation, co-

design, and Q&A

enlisting allies in recruitment (guideline), incorporating a design cri-

tique (guideline), use of common vocabularies (challenge), accommo-

dating schedules and adapting the protocol (challenge), participation in

creating tangible artifacts (challenge)

Considering older adults

throughout the development

process – The HCD+ approach

(Sengpiel et al., 2019)

183 older adults aged

46 to 93 (M=66.6,

SD=7.5)

HCD+ with focus group work-

shops, interviews, evaluations

engage with group leaders (guideline), emphasise reciprocity when re-

cruiting (guideline), plan for social engagement (guideline), overesti-

mate the scheduled time (guideline), accommodate participants’ wishes

(guideline), establish (low-technology) fall-backs (guideline), use ab-

stract descriptions of technology (guideline)

Untold Stories in User-Centred

Design of Mobile Health: Prac-

tical Challenges and Strategies

Learned From the Design and

Evaluation of an App for Older

Adults With Heart Failure (Cor-

net et al., 2020)

older adults aged

over 65 (see study

design for number

of participants),

along with clinicians

and external UCD

experts

UCD including patient interviews

(n=24), patient advisory meetings

(n=2), clinician advisory board

(n=0), individual interviews with

2 cardiologists (n=0), observation

of clinical encounters with a pa-

tient in the device clinic, usability

evaluation (n=4), usability evalua-

tion (n=12), and heuristic evalua-

tion (n=0)

Deciding on number of iterations (challenge), managing UCD logistics

(challenge), collaborating as multidisciplinary team (challenge), deter-

mining timing and level of stakeholder involvement (challenge), choos-

ing stakeholder representatives (challenge), fostering interactions be-

tween stakeholders and designers (challenge), overcoming designers’

assumptions (challenge), managing project scope and complexity (chal-

lenge), maintaining the innovation equilibrium (challenge), conduction

laboratory or in-the-wild usability sessions (challenge), adapting meth-

ods to end users (challenge), deciding on the number of concurrent eval-

uation methods (challenge)

Human-centred Design of Self-management Health Systems with and for Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines

93

ical observations to yield recommendations for con-

ducting an HCD for SMHS involving older adults,

equally including the oldest old (von Humboldt and

Leal, 2015).

3 METHOD

In this study, a complete HCD process, i.e., inspira-

tion or analysis of context of use and requirements,

ideation of design & prototypes, implementation, and

evaluation (Brown et al., 2008), was conducted in an

iterative manner over the course of four years, from

2016 to 2020.

3.1 Participants

Participants were healthy older adults, being at least

65 years old, and were still able to live independently

at home or in a service flat. In total, 81 participants

(30 identified as male, 51 identified as female) with

ages ranging from 65 to 97 (median=83), and six

moderators and researchers attended at least one of

the different HCD activities.

Participants were recruited in Belgium from 2016

to 2020 via local organisations, i.e., InnovAge (In-

novAge, 2016), service centres (Zorg Leuven, 2020),

and Triamant (Triamant, 2020). In addition, we em-

ployed a snowball technique where participants also

brought us in contact with family, friends, or neigh-

bours who also wanted to participate.

All studies were approved by either the Medical

Ethics Committee (CTC-S60250) or Social and Soci-

etal Ethics Committee (G-2019121931).

3.2 Study Design

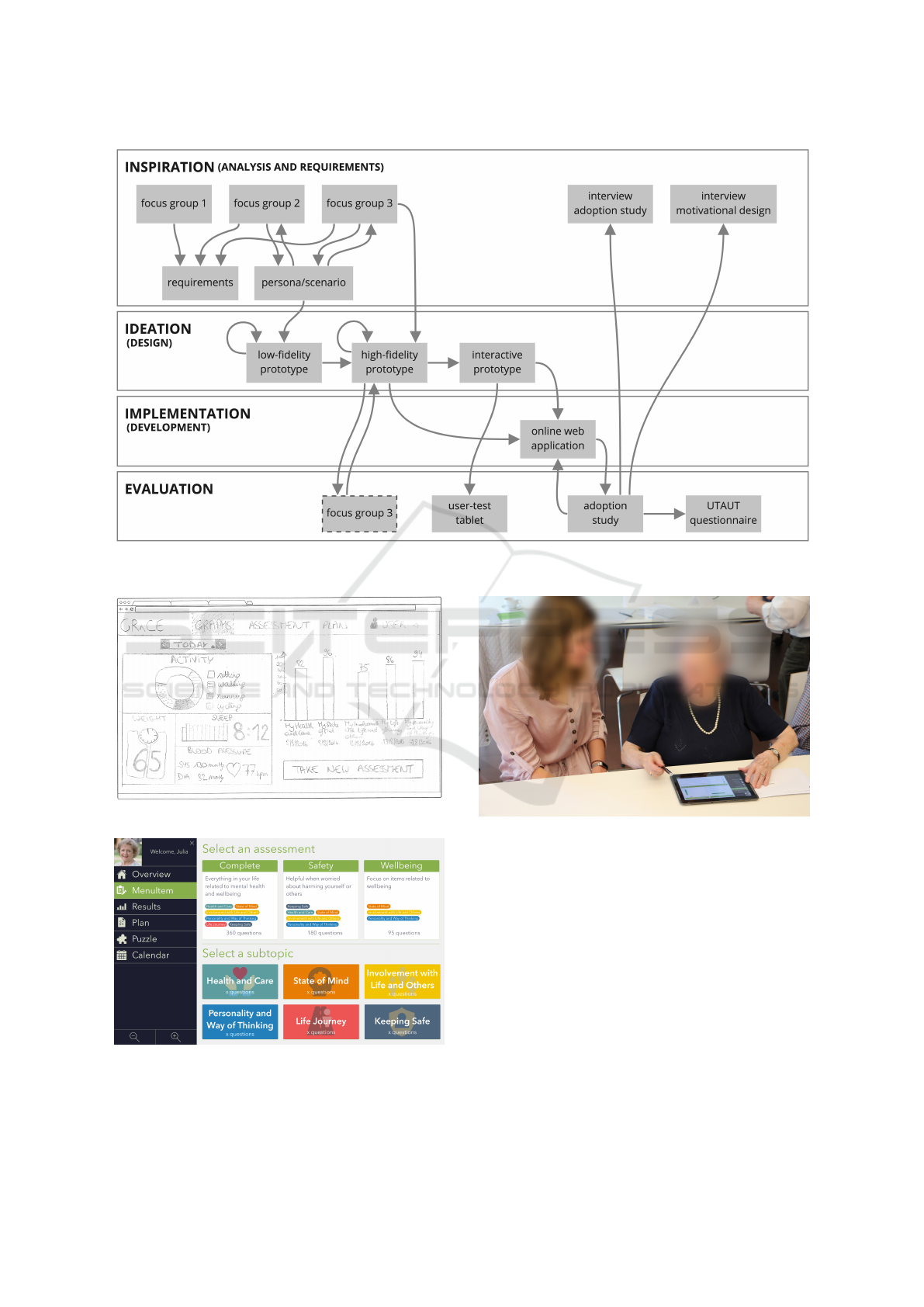

Figure 1 gives an overview of the different HCD

phases and the specific activities that were carried out.

3.2.1 Inspiration

During the inspiration phase, the context of use and

requirements were analysed by means of three focus

group discussions, semi-structured interviews, and

questionnaires.

Focus Group Discussion. Three focus group dis-

cussions were organised to discuss the problem do-

main. Focus group 1 and 2 discussed several topics

related to maintaining a healthy lifestyle, ICT use in

general, and use of SMHS (activity trackers, health

apps, etc). Focus group 3 discussed attitudes towards

a high-fidelity prototype in addition to the topics of

focus group 1 and 2.

Requirements Specification. Based on these prior

focus groups, requirements were enlisted during the

analysis specification. Additionally, a persona and a

context scenario were created to guide the design. A

persona or user model is a “composite user archetype

that represent distinct groupings of behaviours, at-

titudes, aptitudes, goals, and motivations that are

observed and identified during the research phase”

(Cooper et al., 2007).

Interviews. Upon the evaluation of the final appli-

cation, semi-structured interviews with participants

were organised in order to gain insights into their at-

titudes and usage of the system. Additionally, a struc-

tured interview was carried out to understand older

adults attitudes towards motivational designs embed-

ded in SMHS.

3.2.2 Ideation

During the ideation phase, low-fidelity prototypes,

high-fidelity prototypes, and an interactive prototype

were first designed and discussed with project part-

ners at the university and afterwards with the partici-

pants.

Low-Fidelity Prototypes. Low-fidelity prototypes

were used to represent concepts and functionalities

without risking to lose focus due to distracting visual

details. Figure 2 represents a sketch that was made

with pencil and paper.

High-Fidelity Prototypes. Next, a high-fidelity proto-

type was created to represent the look and feel of the

application using the digital design toolkit Sketch

2

.

An example can be found in figure 3.

Interactive Prototypes. The final prototype was made

interactive with Invision prototyping software

3

.

3.2.3 Implementation

An online web-application was developed using

CodeIgniter web framework

4

, a lightweight PHP

framework that supports a Model-View-Controller

approach. The user interfaces were built with the

Bootstrap framework

5

to provide a responsive layout

and ensure high-quality interaction through pre-built

components and JavaScript plugins. Data was stored

in a MySQL database

6

. Figure 4 illustrates the final

SMHS application.

2

Sketch B.V. (2021). The digital design toolkit.

3

Invision Inc. (2021). Digital product designplatform

4

EllisLab (2021). CodeIgniter web framework.

5

MIT. (2021). Bootstrap.

6

Oracle Corporation. (2021). Mysql.

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

94

Figure 1: Overview of the different activities that were part of the human-centred design process of self-management health

systems with older adults.

Figure 2: Low-fidelity prototype.

Figure 3: High-fidelity prototype.

3.2.4 Evaluation

The evaluation phase consisted of formative usabil-

ity testing, summative usability testing, an adoption

Figure 4: Older adult using the online web-application in

tablet mode.

study, and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use

of Technologies (UTAUT) questionnaire to poll for

acceptance.

Formative Usability Test. Formative usability tests

were carried out using high-fidelity prototypes. For-

mative usability tests are rapid and more informal user

tests; users are given realistic tasks and asked to think

aloud while carrying them out. As designers gain in-

sights into the user’s mind while interacting with the

prototype (Cooper et al., 2007). These tests help to

give form to the design.

Adoption Study. Finally, an adoption study was set

up. Older adults used the application over the course

Human-centred Design of Self-management Health Systems with and for Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines

95

of two weeks, in order to investigate the users’ actual

interactive behaviours through user metrics.

Questionnaires. As the experience of this adoption

study shaped their attitudes towards SMHS, a UTAUT

questionnaire (De Witte and Van Daele, 2017) was

provided to all participants. This UTAUT ques-

tionnaire polled for behavioural intention to use the

SMHS and in particular investigated perceived ease-

of-use, usefulness, social influence, and facilitating

conditions.

3.3 Analysis

Noteworthy methodological findings were docu-

mented and discussed with the present researchers af-

ter every phase. In addition, methodological annota-

tions were made during the analysis of the transcripts

which included focus group discussions and inter-

views. Based on this information related to method-

ological observations, a thematic analysis (Clarke and

Braun, 2014) was conducted. First, all transcripts

were studied and nodes were created individually by

two researchers (ID and VVA) who went through the

entire HCD process. In the second iteration, ID de-

fined patterns and clustered nodes in initial themes

which were reviewed by VVA. Afterwards, both ID

and VVA discussed findings until an agreement was

reached and a thematic map created. Finally, these

themes and thematic map were revised by two other

researchers (JG and KG), who were also present dur-

ing at least one phase of the HCD process. This re-

sulted in the final set of themes.

4 RESULTS

Four themes were developed based on the thematic

analysis of methodological observations made during

the HCD process: ‘a life course marked by grand ex-

periences’, ‘a discomfort with unknown digital tech-

nologies’, ‘impact of age-related impairments’, and

‘relatedness as core to research participation’.

4.1 A Life Course Marked by Grand

Experiences

The first theme addresses the full lives lived by older

adults, characterised by joy, but equally misfortune

and grief. Shared naturally and unprompted, these

life experiences often carried significant emotional

weight and permeated all activities of the HCD pro-

cess. For example, during the introduction round of

the focus groups discussion, participants introduced

themselves by name and in one breath recounted per-

sonal details on dramatic events that occurred during

their lifetime.

“Eh... What could I say. Yes, I ended up here be-

cause my wife got a stroke, four years ago. Four

years, well let’s say it started in 2009, at Easter

[tells story of wife who fell ill, was hospitalized and

then moved into a nursing home]. Then they asked

me, why do you keep travelling between here and

your home to take care of your wife, there is a flat

available; and so, since 2013, I reside here.” – man

aged 90

Many participants had lost a loved one and shared

their sorrow. Others talked about the impact of a

chronic or life-threatening disease.

“This morning for example, I went to the hospital

for a consultation concerning my heart. I have to

go every year, and when the results are ready, my

GP will give them to me [...]” – woman aged 81

Naturally, researchers then paused to offer a mo-

ment of thought or consolation. As a consequence,

sufficient time was needed for welcoming and small

talk, e.g., an introductory round during a focus group

discussion was estimated to take up 15 minutes, but

took up 45 minutes to welcome all nine participants.

In addition, a particular recurring pressing topic

was their dire financial situation and related chal-

lenges, brought forward by a lack of a proper pension.

“They can say ‘you have to eat healthy’, but what

is healthy? Five pieces of fruit a day? You have to

buy five pieces of fruit in the store, that is expensive,

you know. We will not get there with our pension

alone...” – woman aged 79

“These are more serious problems, financial prob-

lems for example. Our pension is not sufficient.

[conversation on not having sufficient money]” –

woman aged 65

In some participants’ opinion, this was a much

more pressing problem in their life than the need for

an SMHS. This once again impacted the HCD pro-

cess, as it was difficult for some participants to relate

to a technological solution that was perceived as un-

affordable.

In sum, their tense personal histories, associated

with end of life, were introjected in the different activ-

ities of the HCD process and necessitated researchers

to adapt by making room for them.

4.2 A Discomfort with Unknown Digital

Technologies

The second theme addresses the anxieties and distrust

related to the struggle of older adults with current day

computing technologies that resurfaced in the discus-

sions and evaluations of SMHS.

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

96

The majority of participants in our study had lit-

tle to no experience with current day ICT technol-

ogy such as tablets, activity trackers, smartphones,

etc. Often, this was voiced as a conscious rejection

of these technologies by older adults, propelled by a

distrust towards a society that enforces using technol-

ogy.

“I have chosen to spend no, or as little time as pos-

sible, on the computer, because otherwise people

will become a slave of it.” – woman aged 89

Especially during the focus group discussions, it

was noticeable that some participants showed more

interest in discussing the health topics addressed by

SMHS than the technology itself.

“But I thought this session was about other topics

too, not just about computers.” – man aged 88

“Yes, I thought so too, about nutrition and stuff,

what should improve [for a healthy lifestyle].” –

woman aged 65

“We have also other problems than [using] com-

puters, huh.” – man aged 88

If they had realised beforehand, they might not

have participated.

Similarly, some participants were uncomfortable

during the usability evaluations. Some of them had

not realised they would be interacting with an online

application on a tablet and became somewhat anxious

when they heard about having to test an online tool.

So I just have to do this [cf. take blood pressure

measurements] and then I actually do not have to

use [the tablet]? – woman aged 67

This lack of awareness was initially surprising to

researchers as the informed consent did clearly men-

tion the focus on technologies. However, in hindsight,

the lack in technological proficiency may equally ex-

plain a limited understanding of the different activities

that take place as part of an HCD process.

From these observations we understood that un-

derneath many usability issues was the complete lack

of a mental model on interactive (tablet-based) appli-

cations. The majority of participants did not under-

stand the concepts of touch interactions or logging

into a system. For the same reason, formative user

evaluations with paper prototypes or screenshots on

paper were hard to interpret for some participants.

The lack of mental models made it difficult to hypoth-

esise about future usage situations or different kinds

of features they would prefer.

Additionally, we encountered a language barrier

while testing the application. In Dutch, English terms

are common when using digital and networked ap-

plications, e.g., account, password, login. However,

these mongrel words were not part of participants’ vo-

cabulary and therefore not understood.

“an account has always been a [bank] account for

me. Don’t tell me anything else, because I knew an

account in banking, but not in here [cf. the appli-

cation]. And then login...” – man aged 88

The absolute lack of a mental model also sub-

verted our intention to apply a typical usability test-

ing protocol which recommends starting with a non-

obtrusive part, i.e., refraining from guiding users.

In contrast, in our HCD process, our participants

stressed the importance of receiving help.

“I always like them to show me exactly what I have

to do.” – woman aged 79

In sum, this theme foregrounds the need to adapt

HCD processes to compensate for a lack in experience

in using digital technologies to mitigate anxiety and

discomfort.

4.3 Impact of Age-related Impairments

This third theme addresses the diverse manifestations

of age-related decline, as an interplay of mentally,

physically, and emotional effects. During the differ-

ent research activities of the HCD process, we en-

countered participants who had a broad range of im-

pairments. These impairments included, but were not

limited to, impaired vision, reduced hearing, mobility

limitations, and ailments as a consequence of chronic

diseases. More often than not, participants had sev-

eral of these ailments. As a consequence, and perhaps

most characteristically, we found our HCD process

characterised by a slowness in actions. However, at

the same time this was giving way to tranquillity and

ample time for reflection.

The age-related impairments necessitated several

accommodations. With respect to mobility, it was

paramount that studies were organised nearby partic-

ipants. For one-on-one interviews or user-tests, the

researcher went to the participant’s home. For fo-

cus group discussions or user-tests with multiple par-

ticipants, a room in a local services centre was re-

served. It was ascertained that these rooms were on

the ground floor, thus easily accessible for everyone.

In addition, for participants who wanted to join a ses-

sion but had problems reaching the location, transport

was provided by one of the researchers who picked up

and dropped off participants at home.

In addition, to address visual impairments, we

found it essential to provide all documents, i.e., in-

formation, informed consents, feedback forms, and

increased font size. Furthermore, when testing pro-

totypes, designs were made sufficiently large to make

them apprehensible despite visual impairments. As

such, screenshots were printed in A3 format by de-

fault.

Human-centred Design of Self-management Health Systems with and for Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines

97

Finally, participants also indicated the importance

of talking loud and clear and in isolation. This was

particularly demanding in the moderation of focus

group discussions. The moderator had to ensure that

only one person was talking at the same time, but

equally that everyone talked loud enough or repeated

arguments when necessary.

Repeating and paraphrasing also helped partic-

ipants in processing information and mitigated the

times that attention fleeted.

“What is the actual question, because...” – man

aged 82

This slower processing of information and lesser

cognitive load manageable by the participants became

particularly prominent when conducting evaluations

by means of questionnaires; the shape of the question

and the length of the questionnaire presented difficul-

ties. In the scientific validated questionnaires that we

used, the same construct was often polled using multi-

ple items. This makes these questionnaires quite long

and, in turn, harder for the older participants to sus-

tain attention and complete them in a reliable man-

ner. In addition, negatively formulated questions were

found problematic, as we noted that participants often

marked the opposite answer of what they intended to

answer.

Therefore, it was paramount to orally present

questions and verify answers in a structured interview

format. It helped when participants could verbally

rate their experiences. This also allowed researchers

to rectify errors due to negative phrasing.

As a result, there was a need for a slower pace,

which also brought a sense of perspective. Partici-

pants were often relaxed about these limitations and

adopted a mindset that embraced a lifespan perspec-

tive on ageing.

“Glad we’re still alive.” – woman aged 84

Overall, this theme highlights that every activ-

ity in the HCD process took more time because of

the diverse age-related impairments. This also meant

that less ‘content’ could be dealt with. However, the

slower pace also brought along a relaxing atmosphere.

4.4 Relatedness as Core to Research

Participation

The final theme addresses the inherent social nature

of the HCD process, as a sense of relatedness was a

primordial motive for participants to take part in the

research. At the same time, this need for relatedness

risked obscuring the actual research activities that re-

searchers intended to carry out.

Since it was important to put participants at ease,

a familiar and pleasant setting was chosen to conduct

all research studies; activities took place at the par-

ticipant’s home or a local service centre familiar to

the participants. Moreover, we ensured everyone was

welcomed personally and were offered coffee and bis-

cuits to create a setting in which participants would

feel comfortable. However, the downside of this in-

formal atmosphere was that the actual research pur-

pose was less clear and perhaps less respected. Dur-

ing focus group discussions, participants often devi-

ated from the subject, and it was not always easy to

bring them back to focus on the matter at hand. Dur-

ing interviews, participants seemed unburdened by

the researchers’ agenda. This unawareness of the situ-

ation showed in some participants arriving 25 minutes

late and subsequently explaining their entire life story.

At the same time, many participants seemed

driven by an altruistic motive to participate in the

study .

“I am doing this for you, and to support your re-

search study.” – man aged 69

During the different contact moments, it was re-

markable that almost all older adults were volunteer-

ing or were a volunteer in the past. They all spend

quite a lot of their time helping other people. This

equally reflected in the research study, as participants

often indicated that they wanted to help out on our

research.

“Pleased I was able to help you; I am glad that it

is over, as you are always thinking about it, but I

will also miss being able to follow up everything

[cf. blood pressure, sleep, activities].” – woman

aged 66

Besides helping out as a volunteer, many older

adults equally had other hobbies or activities like

babysitting, going for a walk, or petanque. As a con-

sequence, many of them had quite the busy schedule.

“For 22 years now, I do not have a job, um, yes,

that’s it. I’ll say it in one sentence: It is wonderful

to be retired.” – man aged 82

Remarkably, many older adults endeavoured such

a busy schedule to fill their days.

Many activities they tend to do have a social as-

pect: joining a walking club, going on a group va-

cation, or being a volunteer. They also emphasised

the importance of social interactions. Therefore, we

suspect that some older adults participated in these

studies primarily to maintain social contact.

“contact, social contact is very important. It is for

that reason that I am also a volunteer. I’m out of

the house for about 70 to 80%, just to forget the

grief of my wife who passed away... and that helps

a lot. I even play petanque with my grandchildren

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

98

three times a week. Those are all things that take

time.” – man aged 76

In sum, this last theme indicates that the different

research activities were primarily a means for relat-

ing to other participants or the researchers for many

participants. During the HCD process, there needed

to be sufficient room for small talk. As mentioned

before, participants found it important to share per-

sonal experiences, with conversations often deviating

to chitchat. As a consequence, formalities faded and

adhering to research protocols was challenging.

5 DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the intricacies of involv-

ing older adults in the design of SMHS. The different

themes confirm the need for adaptation of an HCD

process when designing health technologies for the

group of older adults including the oldest old.

The first theme identifies that older adults bring

a life marked by grand experiences with them that

interweave into the diverse HCD experiences. Sec-

ond, we unearthed a strained relationship with digital

technologies, often unknown and unwanted. Third,

we found that different age-related impairments man-

ifest in myriad ways, bringing slowness and tranquil-

lity into the HCD activities. Finally, we found that a

sense of relatedness was essential to participate in the

HCD activities that sometimes complicated the actual

research. The four themes highlight the need for tun-

ing the HCD process and brings the specific role of the

HCD researcher to the foreground. Below, we discuss

this further and relate our findings to prior work.

The Importance of Careful Recruitment and En-

listing of Participants. Given that older adults lack

mental models on interactive technologies, it also im-

plied that it is more difficult for them to understand

what an HCD study actually entails. According to

(Sengpiel et al., 2019; Martin-Hammond et al., 2018;

Czaja et al., 2019), it is therefore important to ensure

a proper understanding before signing up, which was

confirmed in our study. At the same time, this en-

tails the risk of involving only the more tech-savvy

participants with a pre-existing interest in health or

technology, resulting in a biased sample. Moreover,

verbose and lengthy informed consent forms are un-

likely to help. It is therefore important to adjust the

expectations of both researchers and participants prior

to signing up and before each research activity, in or-

der to provide a respectful and useful framework for

everyone. The use of video prompts that illustrate

the problem space (Lindsay et al., 2012) may support

this communication. Pilot testing to identify possible

threats or problems can equally help to gain additional

insights and optimise the recruitment process (Czaja

et al., 2019).

The Challenge of Abstraction in Prototypes. Due

to participants often having low mobile device profi-

ciency and lacking a mental model on using technolo-

gies, it was found difficult to hypothesise about future

innovations. These findings are in line with previous

work (Duh et al., 2016; Lindsay et al., 2012),yet con-

trast with (Sengpiel et al., 2019), who suggested to

rather use abstract descriptions of technology.

The Need for Conscientious HCI Researchers.

Given the vulnerabilities and personal histories of this

older population, there is a need for HCI researchers

who are both empathetic and direct. Researchers

need sensitivity and integrity, to show respect and

give room to dire experiences, yet need to ensure that

structured sessions are kept on track and research fo-

cus is maintained. Moreover, researchers need to en-

sure that all participants are involved during the ses-

sion. When topics fade due to participants trailing off,

it is the role of the researcher to redirect them to the

study in a clear yet empathetic way.

The importance of making room for small talk and

support socialising confirms previous work (Sengpiel

et al., 2019; Davidson and Jensen, 2013a; Chaudhry

et al., 2016). It is at all costs necessary to avoid that

participants get the feeling that they have to pass a

(medical or neuropsychological) test; even more than

with any other age category, the emphasis should be

on ‘do not blame the user’ (Crumlish and Malone,

2009). The crucial role of the researcher is to bal-

ance informal small talk with adequate structure and

guidance, which also confirms results from (Xie et al.,

2012; Lindsay et al., 2012).

Research from (Davidson and Jensen, 2013a; Sen-

gpiel et al., 2019) therefore indicates that it is impor-

tant to be flexible and to adapt to the needs of the

participants. Moreover, providing a safe environment

and additional training could help participants to gain

the confidence they need, which confirms the work by

(Harrington et al., 2018).

To balance all these conflicting demands, having

multiple researchers present in order to provide assis-

tance is not a luxury, but rather mandatory.

5.1 Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study and related work

analysed, we end this paper with a set of recommen-

dations to guide a HCD process of SMHS involv-

ing older adults, structured according to the different

Human-centred Design of Self-management Health Systems with and for Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines

99

phases and activities of a HCD process.

5.1.1 General Recommendations

Every research study starts with the recruitment of

participants. It is essential to (1) find a balanced com-

position of participants with different backgrounds

and (2) align expectations between participants and

researchers. By (3) reaching out to local contact

points or organisations a varied sample of partici-

pants can be reached, and this can lower their thresh-

old for participation. It is also beneficial to (4) organ-

ise sessions nearby participants, ideally in their home

environment so they do not need to move. However,

when organising group sessions, one should (5) take

care of transport in order to make sure that all inter-

ested participants can join.

Given that participants often take part in research

studies as a networking event or to help out the re-

searchers, it is important to listen to the participant,

(6) leaving room and time for social interludes.

5.1.2 Inspiration Phase Recommendations

Interviews and Focus Group Discussions. During

conversations, it is important to (7) talk loud enough,

and (8) provide a clear structure in the session. It can

help to make things specific and (9) provide tangible

examples, as it is hard for participants to hypothesise

due to their lack of experiences.

Particularly focus group discussions need multiple

moderators and researchers, both for providing gen-

eral and practical assistance. The moderator should

make sure to (10) get everyone on board and thus

(11) paraphrase regularly what was discussed, but

should also (12) provide practical assistance and help

participants to write, bring coffee, etc.

Given that there should be room for small talk, but

also due to the attention span of older adults, every-

thing proceeds slower. Therefore, it is suggested to

(13) limit the topics that need to be discussed. A rule

of thumb could be to multiply the estimated timing

by two. Furthermore, by providing sufficient breaks,

participants also have the (14) possibility to stand up

in between. To ensure that everyone has had enough

time to voice their concerns, it could also help to

(15) limit the number of participants to a maximum

of 6.

5.1.3 Ideation Phase Recommendations

Low-Fidelity Prototypes. Although low-fidelity

prototypes are interesting to test internally with

proxies, it was hard for participants to understand the

interactions based on such a prototype. Participants

often had little ICT experience, thus lacking a mental

model. Therefore, we suggest to (16) avoid testing

paper-prototypes with older adults.

High-Fidelity/Interactive Prototypes. When present-

ing information to participants, it was important to

avoid English terms and (17) translate all words into

their native language, even if these terms are official

mongrel words.

5.1.4 Evaluation Phase Recommendations

Formative/Summative Usability Test. When con-

ducting user-tests, it is important to start with (18) re-

assuring participants that they cannot do anything

wrong. At all cost, it should be (19) avoided that

participants feel that they are tested, instead of the

application. For participants without any ICT experi-

ence, it can be hard to understand what to do. There-

fore (20) providing alternatives for participants who

have no mental model on using a technology can help

them. Especially for user-tests with multiple partici-

pants, it is beneficial to have (21) one moderator or

researcher for every 3 to 4 participants. These are

necessary when participants are stuck or have practi-

cal questions.

Adoption Study. Before starting the experiment it is

important to (22) comfort participants and (23) try out

all features together so participants can first experi-

ment in a safe environment.

Questionnaires. First of all, it is important to

(24) avoid questionnaires that are too long, as par-

ticipants’ attention will decrease, resulting in incom-

plete or incorrectly filled out questionnaires. Further-

more, (25) avoid negative phrased questions as these

can be harder to interpret. In addition, when possible,

(26) ask questions orally.

6 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

For the participants’ recruitment, we aimed for a het-

erogeneous sample in which we also included the old-

est old. However, given that participants chose them-

selves whether to participate or not, self-selection was

inevitable. This could also introduce bias in the find-

ings by favouring those who were cognitively or phys-

ically stronger. However, given the transitional qual-

ity of ageing (Durick et al., 2013), it is hard to dis-

tinguish participants based on only age or ability, as

this would simplify the ageing process without hav-

ing a sound theory (Vines et al., 2015). Moreover,

we acknowledge that this research study has come to

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

100

life by studying our own practicalities and that it is

limited to these experiences on what did or did not

work. Therefore, future work is necessary to validate

our recommendations.

7 CONCLUSION

In this study, we report findings based on a four-year

HCD process conducted with 81 older adults (median

age=83). Based on a thematic analysis, four themes

emerged: ‘a life course marked by grand experi-

ences’, ‘a discomfort with unknown digital technolo-

gies’, ‘impact of age-related impairments’, and ‘relat-

edness as core to research participation’. Moreover,

each theme presents insights and guidelines, which

are summarised in section 5.1. This study contributes

by offering lessons learned in the different phases of

an HCD process. Our aim is that these guidelines

can help future researchers to undertake more effec-

tive and useful study designs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank InnovAge, Zorg Leuven, and

Triamant for their participation, as well as all partici-

pants for helping out during one or multiple phases in

this research study.

REFERENCES

Amaro, A. C., Rodrigues, R., and Oliveira, L. (2020).

Engaging older adults in participatory and intergen-

erational design teams and processes: a systematic

review of the current investigation. ESSACHESS–

Journal for Communication Studies, 13(2 (26)):157–

181.

Association for Computing Machinery (2021). Acm digital

library.

Brown, T. et al. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard business

review, 86(6):84.

Chaudhry, B., Duarte, M., Chawla, N. V., and Dasgupta,

D. (2016). Developing health technologies for older

adults: methodological and ethical considerations. In

Proceedings of the 10th EAI International Conference

on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare,

pages 330–332.

Clarke, V. and Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. In En-

cyclopedia of critical psychology, pages 1947–1952.

Springer.

Cooley, M. (1996). On human-machine symbiosis. In Hu-

man Machine Symbiosis, pages 69–100. Springer.

Cooper, A., Reimann, R., and Cronin, D. (2007). About face

3: the essentials of interaction design. John Wiley &

Sons.

Cornet, V. P., Toscos, T., Bolchini, D., Ghahari, R. R.,

Ahmed, R., Daley, C., Mirro, M. J., and Holden, R. J.

(2020). Untold stories in user-centered design of mo-

bile health: practical challenges and strategies learned

from the design and evaluation of an app for older

adults with heart failure. JMIR mHealth and uHealth,

8(7):e17703.

Crumlish, C. and Malone, E. (2009). Designing social in-

terfaces: Principles, patterns, and practices for im-

proving the user experience. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Czaja, S. J., Boot, W. R., Charness, N., and Rogers, W. A.

(2019). Designing for older adults: Principles and

creative human factors approaches. CRC press.

Davidson, J. L. and Jensen, C. (2013a). Participatory design

with older adults: an analysis of creativity in the de-

sign of mobile healthcare applications. In Proceedings

of the 9th ACM Conference on Creativity & Cognition,

pages 114–123.

Davidson, J. L. and Jensen, C. (2013b). What health top-

ics older adults want to track: a participatory design

study. In Proceedings of the 15th International ACM

SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessi-

bility, pages 1–8.

De Witte, N. and Van Daele, T. (2017). Vlaamse UTAUT-

vragenlijst.

D’Haeseleer, I., Gerling, K., Schreurs, D., Vanrumste, B.,

and Vanden Abeele, V. (2019). Ageing is not a dis-

ease: Pitfalls for the acceptance of self-management

health systems supporting healthy ageing. In The 21st

International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Com-

puters and Accessibility, pages 286–298.

Duh, E. S., Guna, J., Poga

ˇ

cnik, M., and Sodnik, J. (2016).

Applications of paper and interactive prototypes in de-

signing telecare services for older adults. Journal of

medical systems, 40(4):92.

Duque, E., Fonseca, G., Vieira, H., Gontijo, G., and Ishitani,

L. (2019). A systematic literature review on user cen-

tered design and participatory design with older peo-

ple.

Durick, J., Robertson, T., Brereton, M., Vetere, F., and

Nansen, B. (2013). Dispelling ageing myths in tech-

nology design. In Proceedings of the 25th Australian

Computer-Human Interaction Conference: Augmen-

tation, Application, Innovation, Collaboration, pages

467–476.

Gould, J. D. and Lewis, C. (1985). Designing for usability:

key principles and what designers think. Communica-

tions of the ACM, 28(3):300–311.

Harrington, C. N., Wilcox, L., Connelly, K., Rogers, W.,

and Sanford, J. (2018). Designing health and fit-

ness apps with older adults: Examining the value of

experience-based co-design.

Heart, T. and Kalderon, E. (2013). Older adults: Are they

ready to adopt health-related ICT? International Jour-

nal of Medical Informatics, 82(11):e209–e231.

InnovAge (2016). Innovage.

ISO, I. O. f. S. (2019). Iso 9241–210: 2019 (en) er-

Human-centred Design of Self-management Health Systems with and for Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines

101

gonomics of human-system interaction—part 210:

Human-centred design for interactive systems.

Kononova, A., Li, L., Kamp, K., Bowen, M., Rikard, R.,

Cotten, S., and Peng, W. (2019). The use of wear-

able activity trackers among older adults: Focus group

study of tracker perceptions, motivators, and barriers

in the maintenance stage of behavior change. JMIR

mHealth and uHealth, 7(4):e9832.

Lindsay, S., Jackson, D., Schofield, G., and Olivier, P.

(2012). Engaging older people using participatory de-

sign. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on hu-

man factors in computing systems, pages 1199–1208.

Martin-Hammond, A., Vemireddy, S., and Rao, K. (2018).

Engaging older adults in the participatory design of

intelligent health search tools. In Proceedings of the

12th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Com-

puting Technologies for Healthcare, pages 280–284.

Mehrotra, S., Motti, V. G., Frijns, H., Akkoc, T., Yengec¸,

S. B., Calik, O., Peeters, M. M., and Neerincx, M. A.

(2016). Embodied conversational interfaces for the

elderly user. In Proceedings of the 8th Indian Confer-

ence on Human Computer Interaction, pages 90–95.

Muller, M. J. and Kuhn, S. (1993). Participatory design.

Communications of the ACM, 36(6):24–28.

Nunes, F., Verdezoto, N., Fitzpatrick, G., Kyng, M.,

Gr

¨

onvall, E., and Storni, C. (2015). Self-care tech-

nologies in hci: Trends, tensions, and opportunities.

ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction

(TOCHI), 22(6):1–45.

Peek, S. T., Luijkx, K. G., Rijnaard, M. D., Nieboer, M. E.,

van der Voort, C. S., Aarts, S., van Hoof, J., Vrijhoef,

H. J., and Wouters, E. J. (2016). Older adults’ reasons

for using technology while aging in place. Gerontol-

ogy, 62(2):226–237.

Sanders, E. B. (2002). From user-centered to participatory

design approaches. Design and the social sciences:

Making connections, 1(8):1.

Sengpiel, M., Volkmann, T., and Jochems, N. (2019).

Considering older adults throughout the development

process–the hcd+ approach. Proceedings of the Hu-

man Factors and Ergonomics Society Europe, pages

5–15.

Sintonen, S. and Immonen, M. (2013). Telecare services

for aging people: Assessment of critical factors influ-

encing the adoption intention. Computers in Human

Behavior, 29(4):1307–1317.

Triamant (2020). Triamant group.

Vines, J., Pritchard, G., Wright, P., Olivier, P., and Brit-

tain, K. (2015). An Age-Old Problem: Examining the

Discourses of Ageing in HCI and Strategies for Fu-

ture Research. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact.,

22(1):2:1–2:27.

Volkmann, T., Sengpiel, M., and Jochems, N. (2016). Histo-

rytelling: a website for the elderly a human-centered

design approach. In Proceedings of the 9th Nordic

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, pages

1–6.

von Humboldt, S. and Leal, I. (2015). The old and the

oldest-old: Do they have different perspectives on ad-

justment to aging? International Journal of Gerontol-

ogy, 9(3):156–160.

Xie, B., Yeh, T., Walsh, G., Watkins, I., and Huang, M.

(2012). Co-designing an e-health tutorial for older

adults. In Proceedings of the 2012 iConference, pages

240–247.

Zorg Leuven (2020). Zorg leuven. (Accessed on

03/12/2020).

ICT4AWE 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

102