Discrimination between Social Groups: The Influence of

Inclusiveness-Enhancing Mechanisms on Trade

Stefano Bennati

1,2 a

, Catholijn M. Jonker

2 b

, Pradeep K. Murukannaiah

2 c

,

Rhythima Shinde

2,3 d

and Tim Verwaart

2

1

Computational Social Science, ETH Zurich, Clausiusstrasse 50, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland

2

Intelligent Systems, EEMCS, TU Delft, Van Mourik Broekmanweg 6, 2628 XE, Delft, The Netherlands

3

Ecological Systems Design, ETH Zurich, John-von-Neumann-Weg 9, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland

Keywords:

Discrimination, Agent-based Simulation, Values, Inclusion.

Abstract:

The bargaining power of prosumers in a market can vary significantly. Participants can range from industrial

participants to powerful and less powerful citizens. Existing trade mechanisms in such markets, e.g., in rural

India’s energy trade market, show occurrences of discrimination, exclusion, and unfairness. We study how dis-

crimination affects market access, efficiency, and demand satisfaction for the discriminating and discriminated

groups via an agent-based simulation, incorporating the available real data. We introduce a mechanism for

such markets that is designed for the values of inclusion and equal opportunities. The crux of our mechanism

is that goods are divided into smaller units, as determined by the market participants’ surplus and demands,

and traded anonymously via agents representing the prosumers. We evaluate six hypotheses in a case study

about energy trade in rural India, where members of a caste known as Dalits are discriminated by Others.

We show that anonymization contributes to the value of inclusion, and the combination of anonymization and

inclusion contributes to equal opportunities with respect to market access for both Dalits and Others.

1 INTRODUCTION

The possibility of tracing goods to their production

and delivery is important for accountability. How-

ever, knowing the origin of goods or of payments can

enable social discrimination based on, e.g., ethnicity,

gender, or caste. The shorter the link between buyers

and sellers, the more poignant the opportunity for dis-

crimination. In physical markets, the link is direct as

personal contact is required for transactions.

Energy trading in rural India is a clear setting to

study discrimination in a physical market. Large parts

of rural India lack an infrastructure for automated en-

ergy distribution. Solar panels can be a solution for

generating energy locally but require a local market

for distributing surplus energy. The local market is

currently realized by trading batteries. This exchange

requires personal contact, implying that the origin of

energy can be established. Therefore, this trade cre-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7603-8564

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4780-7461

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1261-6908

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3435-3202

ates an opportunity for social discrimination.

A specific type of discrimination present in the

Indian markets is the discrimination between mem-

bers of higher castes and Dalits (historically, the low-

est caste in India). Specifically, individuals of a high

caste may not buy energy produced by Dalits since

the former may consider the energy produced by Dal-

its as “impure.” The high caste individuals may not

discriminate when selling the energy to the Dalits.

Ideally, increasing personal distance by mediation

should reduce the opportunity (not the cause) for dis-

crimination. However, if the mediator is a Dalit, the

market is prone to the same discrimination as when

the producer is a Dalit. In contrast, if the mediator is

of a high caste, discrimination can still happen. The

mediator, to maintain reputation or to simply follow

the social rules, may block trade across caste lines,

practically creating two separate markets.

Considering the factors above, we propose medi-

ation through a local grid as a technological alterna-

tive. We compare different market mechanisms with

respect to their discriminatory potential and study

the effect of these mechanisms on the market per-

Bennati, S., Jonker, C., Murukannaiah, P., Shinde, R. and Verwaart, T.

Discrimination between Social Groups: The Influence of Inclusiveness-Enhancing Mechanisms on Trade.

DOI: 10.5220/0010544100710082

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications (SIMULTECH 2021), pages 71-82

ISBN: 978-989-758-528-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

71

formance. In particular, we study the effect of dis-

crimination on the volumes of trade between people

from different caste groups and market efficiency in

order to answer the following research question: Can

we reduce the effect of discrimination on market effi-

ciency and trade volumes between (caste) groups by

anonymizing trade via agent-based mediation?

Answering this question is nontrivial. First, a vari-

ety of factors, including the distribution of individuals

across social groups in a population, their production

and consumption characteristics, the market type, and

the trade mechanisms supported by it, influence the

market outcome. Thus, the influence of discrimina-

tion and the mechanisms to reduce the influence must

be studied in complex setting, including the additional

factors that influence outcomes. Second, introducing

and studying such mechanisms in the wild, in a real

energy market, is not feasible.

We seek to answer the research question above via

a rigorous agent-based market simulation. We com-

pare market access of the different groups, trade vol-

umes between groups, and overall market efficiency

in mediated and non-mediated markets. To gain fur-

ther insights on the effects of discrimination, we sim-

ulate different trading protocols considering transac-

tion size and trading rounds. Our simulations are

based on the available data about the size and income

of different social groups in rural India, and on their

energy production and consumption characteristics.

Our contribution in this paper is three fold.

1. We describe a formal model to capture the influ-

ence of discrimination on market measures.

2. We develop the first agent-based model (to the

best of our knowledge), simulating caste-based

discrimination in an energy market.

3. We propose and evaluate two simple yet effective

mechanisms (bid splitting and multibidding) to re-

duce the influence of discrimination.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Sec-

tion 2 describes related works. Section 3 describes

the formal model we develop to study discrimination

in a market. Section 4 describes the mechanisms we

introduce to reduce discrimination, and the the simu-

lation model we develop to study the influence of the

proposed mechanisms. Section 5 describes our hy-

potheses and the experiments we conduct. Section 6

discusses the results of our experiments. Section 7

concludes the paper, highlighting key findings.

2 RELATED WORK

We provide a background decentralized electrifica-

tion in India, and review works on agent-based energy

trade and caste-based discrimination in India.

2.1 Decentralized Electrification

In a country like India, connecting everyone to a cen-

tralized power grid is problematic due to rough ter-

rains and patchy rural settlements (Census of India,

2011), and high costs for distribution companies. As

of August 2019, 25 million Indian households still do

not have electricity (REC Limited, 2019).

Decentralized solutions such as solar home sys-

tems (SHS)—rooftops with integrated solar Photo-

Voltaic (PV) panels—and PV microgrids (capable of

supplying electricity to a village for domestic use) are

preferable (Bhattacharyya, 2006; Chaurey and Kand-

pal, 2010; Cust et al., 2007). However, long-term

electrification projects are susceptible to many socio-

cultural, economic, and technical factors (Urmee and

Md, 2016; Singh et al., 2017; Trotter, 2016). For ex-

ample, the choice of target users, and the identifica-

tion, appointment of a trusted local leader, and com-

munity participation is important.

2.2 Agent-based Electricity Trade

As Kirman (1989) argued in his seminal paper, one

should study not only market equilibria, but also con-

sider the individual behavior of the traders. For this

purpose, a whole research line in agent-based eco-

nomics has been developed. Our work can be re-

lated to the work about choice functions (Nadal et al.,

1998), specifically, what is the influence of an agent’s

knowledge about the caste system and the status of its

trade partners on the agent’s choice function?

The literature on agent-based electricity trade dis-

cusses agents that optimize their own utility, e.g.,

maximizing profits, or maximize utility of the market

consumers needs (Bower and Bunn, 1999; Ilic et al.,

2012; Sha and Catalão, 2015; Tushar et al., 2014). Li

et al. (2011) and Weidlich and Veit (2008) discuss bid-

ding strategy models, indicating that new optimiza-

tion functions should be developed to take into ac-

count the increased uncertainty of energy generation

and demands of the renewable energy markets.

Concepts used in bidding and acceptance strate-

gies include memory and trust (i.e., number of times

the buyer and seller meet in the market). In this pro-

cess of exchange, agents also learn about the other

agents and change their behavior via different meth-

ods, e.g., comparing their own profits with others

(Chen, 2012; Winker and Gilli, 2001). Most of the

price matching is done via a passive role of buyer in

the market where seller decides a price (Lee et al.,

2015). Other methods discussed to deal with uncer-

SIMULTECH 2021 - 11th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications

72

tainty in the market and bidding strategies, are e.g.,

(Bower and Bunn, 1999; Sha and Catalão, 2015). Fi-

nally, simulation settings for experimental research

are discussed in (Ilic et al., 2012; Saad et al., 2011),

where different evaluation measures, e.g., social wel-

fare and efficiency of the energy exchange are studied.

The works above cover different aspects of agent-

based modeling in energy trade. However, none of

those are used to study the effects of discrimination,

as we do, in the context of peer-to-peer energy trade.

2.3 Caste-based Discrimination

There is ample evidence for caste-based discrimina-

tion in India in almost all sectors (Thorat and Neu-

man, 2012). Betancourt and Gleason (2000) find

that a higher proportion of individuals of Scheduled

Castes (and Muslims) in the rural areas of a district

leads to a lowering of the provision of medical and

educational services to that district, and observe this

across all states, providing a direct evidence for dis-

crimination. Borooah et al. (2014) observe that a

household’s position in the distributional ladder and

its chances of being poor are largely dependent on its

caste. They find that, even when two households have

comparable assets, the household of lower caste gets

rewarded lower than the higher caste household. For

example, buffaloes in a Scheduled Caste household

did not earn (via sale of milk) as much as they did in a

higher caste household for “untouchability” reasons.

The role of caste in energy exchange is largely un-

explored. Singh et al. (2017) show that castes and

sections of the community which did not trust each

other for historical reasons were not ready to share

energy with each other. In an empirical field study

by Shinde (2017), experts from nine different India-

based projects confirm the existence of caste-based

discrimination in energy sharing. In particular, even

though caste-based discrimination is illegal, people

belonging to higher castes still discriminate Dalits and

refuse to buy from Dalits, affecting the trade volume

of batteries between Dalits and Others.

To the best of our knowledge, neither caste-based

discrimination nor the influence of discrimination on

trade in a market have been studied via simulation

models in the current literature. However, other forms

of discrimination have been studied. For instance,

Bullinaria (2018) studies gender-based discrimination

in the setting of career progressions. Takács and

Squazzoni (2015) study how inequality can emerge in

an idealized labor market (without a history of dis-

crimination) due to information asymmetry. Plous

(2003) explains that the stereotypes about low-status

groups, e.g., labelling them as ’lazy’, lead to their dis-

criminatory treatment in a social context.

3 FORMAL MODEL

A population of prosumers is trading energy at a mar-

ket. We define G as the set of all groups. The popu-

lation is divided into two subgroups: D ∈ G are the

discriminated group and O ∈ G are the others.

At each time step, each agent j in the popula-

tion obtains a production value p

j

and a consumption

value c

j

(the energy needs). At first, an agent uses its

production to satisfy its needs and then turns to the

market to deal with the surplus. We define the surplus

s

j

= p

j

− c

j

. A positive surplus means that the agent

has extra production to sell; a negative surplus means

that the agent has unmet consumption to satisfy. We

subdivide the groups depending on the surplus as fol-

lows. For any group g ∈ G: g

+

= {i ∈ g : s

i

> 0},

g

−

= {i ∈ g : s

i

< 0}. We then define the total surplus

S

g

and the total demand C

g

of a group g as:

S

g

=

∑

i∈g

+

s

i

and C

g

=

∑

i∈g

−

s

i

Trade in the market moves a resource from an

agent with a surplus to an agent with a demand. In the

following, for any two groups g, g

0

∈ G, T

g

0

g

denotes

the total trade from members of group g to members

of group g

0

. The total of all transactions is defined by

totalling the trade in all directions:

τ =

∑

g,g

0

∈G

T

g

0

g

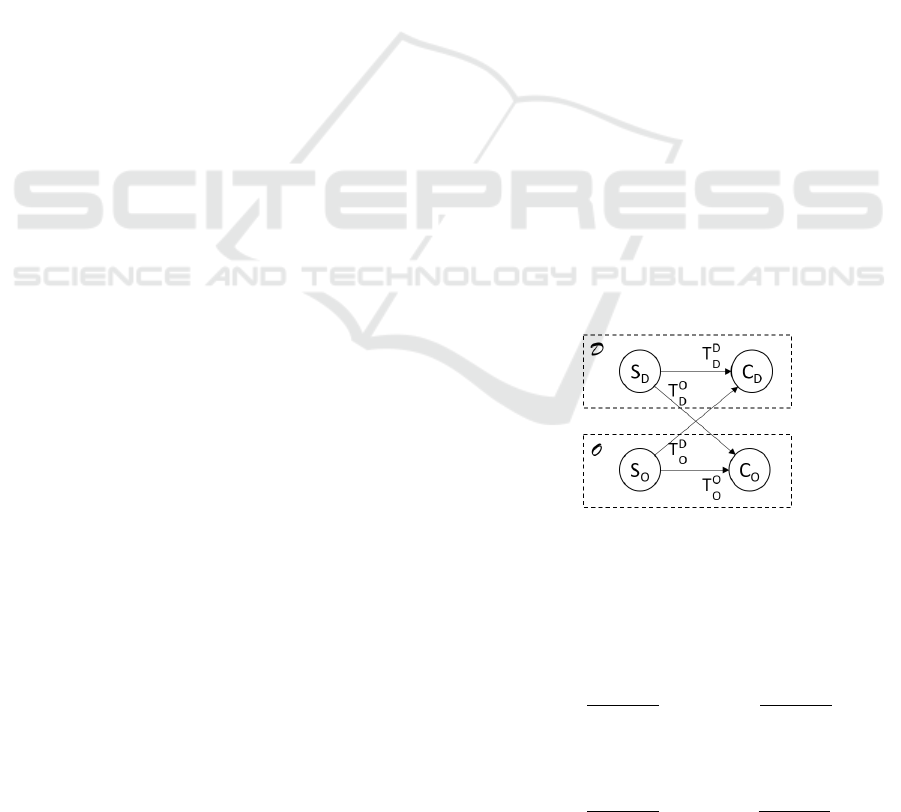

In particular, for only two groups (D and O), τ is

defined as τ = T

D

D

+T

O

D

+T

D

O

+T

O

O

as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: Trade directions between groups D and O.

For the evaluation of the market and its proto-

cols, we introduce measures about demand satisfac-

tion, selling success, and market efficiency.

Demand satisfaction factors are determined as in-

coming trade over demand per group:

η

D

=

T

D

D

+ T

D

O

C

D

and η

O

=

T

O

D

+ T

O

O

C

O

Selling success factors are determined as incom-

ing trade over surplus per group:

θ

D

=

T

D

D

+ T

O

D

S

D

and θ

O

=

T

D

O

+ T

O

O

S

O

Discrimination between Social Groups: The Influence of Inclusiveness-Enhancing Mechanisms on Trade

73

Two groups, g and g

0

∈ G , are said to have equal

opportunity in the market if:

|η

g

− η

g

0

| ≤ ρ

1

and |θ

g

− θ

g

0

| ≤ ρ

2

,

where ρ

1

and ρ

2

are significance margins. In contrast,

the market favors a group g over group g

0

, if:

η

g

− η

g

0

> ρ

1

or θ

g

− θ

g

0

> ρ

2

.

The total amount of trade possible is limited by the

total surplus (it is not possible to trade more energy

than what is produced) and by the total demand (it

does not make sense to trade more energy than what

is asked for). Hence, the total trade possible is:

σ = min{C

D

+C

O

, S

D

+ S

O

}

Market efficiency is defined as total trade over to-

tal possible trade:

γ =

τ

σ

Thus, γ = 1 indicates total market efficiency, but γ < 1

indicates a market in which more demand could have

been satisfied and surplus production is unnecessarily

wasted. The avoidable waste factor of surplus produc-

tion ω is defined as:

ω = 1 − γ

Similarly, the proportion of unmet demands that a

group g ∈ G suffers is defined as δ

g

= 1 − η

g

.

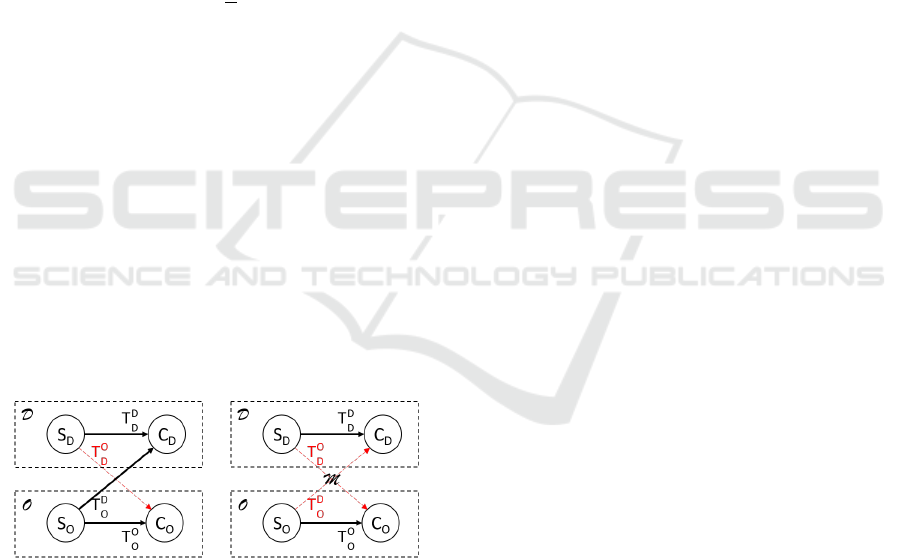

Discrimination. When considering discrimination

in two groups, the effect of discrimination on trade

volumes, in terms of the model, can be described as

the proportions of trade over the trade directions be-

tween and within the two groups as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Left: discrimination on trade from D to O. Right:

market segregation due to the discriminating mediator (m).

4 SIMULATION MODEL

Our description follows the ODD (Overview, Design

concepts, Details) protocol (Grimm et al., 2010).

4.1 Purpose

Our model simulates trade in a prosumer market, in

presence of social discrimination, to understand the

effect of discrimination on the market and to evaluate

a mechanism for reducing discrimination.

4.2 Entities, State Variables, and Scales

The Agents in our model are the energy prosumers,

characterized by the following state variables:

• population to which the agent belongs;

• caste (Dalits or Others);

• (per capita) income; and

• consumption and production values.

The Environment is the market, characterized by the

following state variables:

• market type (bilateral or mediated);

• transaction type (full surplus, bid splitting, or

multibidding);

The Collectives of interest are the agents correspond-

ing to Dalits (D) and Others (O). The following state

variable is defined at the level of the collectives:

• discrimination, which specifies the extent to which

an agent discriminates trade from another agent.

4.3 Process Overview and Scheduling

The Main Process is a SCHEDULER, which executes

one of the following trade protocols, depending on the

transaction type: (1) FULL_SURPLUS_PROTOCOL(),

(2) BID_SPLITTING_PROTOCOL(), and (3) MULTI-

BIDDING_PROTOCOL(). Depending on the protocol,

one or more of the following functions are involved.

• TRADE() executes trades between pairs of agents;

• SPLIT_BIDS() splits bids;

• SELECT_PARTNERS() selects trade partners;

• DISCRIMINATES() determines whether and agent

discriminates trade from another agent; and

• MEASUREMENTS() computes response variables.

One complete run of the model simulates trade

among agents in a population for one day. For each

run, once the agents and the environment are config-

ured, the SCHEDULER, executes one of the the trading

protocols and logs the measurements.

4.4 Design Concepts

4.4.1 Basic Principles

Our simulation depends on market type and transac-

tion type, which determine how trade happens.

SIMULTECH 2021 - 11th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications

74

Market Type. In a bilateral market, the agents di-

rectly trade energy with each other. In a mediated

market, the agents trade energy via a mediator.

In a physical market, bilateral trade means that

the prosumers exchange batteries with each other,

whereas mediated trade means that a mediator col-

lects and redistributes the batteries. In an online mar-

ket, e.g., realized on a smart grid, the grid, acting as a

mediator, collects and distributes energy.

Transaction Type.

• Full surplus: An agent sells its full daily surplus

in one transaction. This setting is intended to cap-

ture how agents trade batteries in a physical mar-

ket, where they buy or sell whole batteries (which

cannot be divided). For simplicity, we assume that

each seller has all of its surplus in one battery.

Thus, each trade (buy or sell) involves one battery.

• Bid splitting models the exchange of energy, where

each production and consumption is divided into

chunks of a maximum size. For example, given a

maximum chunk size of 1, a production of 2.13 is

divided in chunks of sizes 1, 1 and 0.13. Then, each

chunk can, in principle, be sold to a partner with the

matching demand, but the remaining production or

consumption stays with the agent. For instance, in

the example above, if the agent sells two chunks

of size 1, the production of 0.13 remains with it.

The maximum chunk size plays a role in making

the system more or less efficient. We choose the

smallest surplus or demand value across all agents

as the maximum chunk size.

• Multibidding models multiple rounds of bidding in

which the remaining production from one round

can be allocated in the next round to individuals

that still have unsatisfied consumption. In each

round, bid splitting takes place, considering the

smallest surplus or demand value in that round as

the maximum chunk size. Multibidding maximizes

trade efficiency as trading ends when one of pro-

duction or consumption is fully satisfied.

4.4.2 Emergence

The market outcomes directly depend on the trades

that take place. The trades, in turn, depend on the

discriminating behavior of the agents. It is important

to note that the effect of discrimination on multiple

market variables cannot be determined directly. Sev-

eral factors, including the distribution of discriminat-

ing agents, consumption and production characteris-

tics, and trading protocols influence the effect of dis-

crimination on the response variables. Our simulation

seeks to systematically quantify these effects.

4.4.3 Objectives

One the one hand, each agent’s objective is to maxi-

mize trade (sell all surplus or buy for all demand). On

the other hand, some agents may be discriminating

(e.g., to conform to social rules) and thus participate

in some trades but not others.

4.4.4 Interaction

A pair of agents (a seller and a buyer) interact when

they trade energy. Depending on the protocol, (1) an

agent can participate in multiple trades and (2) the

same pair of agents may trade with each other mul-

tiple times, within a trading day.

4.4.5 Stochasticity

• Income is computed stochastically. The income

range is determined according to income distribu-

tion in real data but, with in the range, an income

value is randomly selected.

• Production is computed deterministically from in-

come. Since income is stochastic and production

depends on income, production is also stochastic.

• Consumption is computed, considering the agent’s

income as well as the uncertainty about the future

energy demand. Thus, consumption is stochastic.

• Discrimination behavior is stochastic. A fraction of

agents in the population are treated as discriminat-

ing. A discriminating agent has a certain probabil-

ity of successfully trading with an agent it discrim-

inates. This behavior is realistic since an agent may

not be discriminating all the times.

4.4.6 Observations

We employ the measures of market efficiency (γ), the

demand satisfaction for the two groups (η

D

ad η

O

),

and the selling success of the two groups (θ

D

and θ

O

).

4.5 Input Data

The population, income, and consumption are based

on external datasets summarized below.

Population. We model agent populations after peo-

ple in eight Indian villages, spanning four states:

Andhra Pradesh (AP), Uttar Pradesh (UP), Maharash-

tra (MH), and Rajasthan (RJ). We select these vil-

lages because the Project on Agrarian Relations in

India (PARI), a project that studies economies of dif-

ferent regions in India, surveyed households in these

villages during 2005–2007, providing important data

for our simulation (Rawal and Swaminathan, 2011)

Discrimination between Social Groups: The Influence of Inclusiveness-Enhancing Mechanisms on Trade

75

shown in Table 1. Two key pieces of information we

exploit from this data are the number households and

the percentage of Dalits households for each village.

Table 1: The household composition (of Dalits and Others)

and the mean household income (INR per year) of the eight

Indian villages (Rawal and Swaminathan, 2011) on which

we base our simulations.

Village

Households Mean Income

Total %D D O

Ananthavaram 667 42.4 30,690 93,727

Bukkacherla 292 19.8 19,829 40,596

Kothapalle 372 43.3 26,197 38,962

Harevli 112 36.6 27,540 118,951

Mahatwar 150 58.8 25,077 53,530

Warwat Khanderao 757 32.6 24,843 68,400

Nimshirgaon 250 10.0 41,647 87,393

25 F Gulabewala 204 60.2 25,111 339,078

Income. The PARI data (Rawal and Swaminathan,

2011) includes the distributions of incomes per caste

for each of the eight villages. Table 2 shows examples

of income distributions for three villages.

Table 2: The per capita income distributions of Dalits and

Others for three villages. Data for all eight villages is in

(Rawal and Swaminathan, 2011).

Income Range

Ananth-

avaram

Harevli

Nimsh-

irgaon

(INR per year) D O D O D O

<5,500 39.5 26.3 8037.7 49.4 20.5

5,500–10,000 26.1 14.6 12.5 26.1 27.3 28.2

10,000–20,000 23.6 29.3 7.511.6 16.1 31.4

20,000–30,000 10.8 11.8 0 10.1 1.2 12.1

30,000–40,000 0 4.4 0 4.3 5.9 0

40,000–50,000 0 2.2 0 0 0 3.1

>50,000 0 11.5 0 10.1 0 4.7

Consumption. No datasets, providing consumption

distributions along with income or caste information,

were available for the Indian market. However, the

RECS 2015 report (EIA, 2015) classifies the energy

consumption of US households by their annual in-

come as summarized in Table 3. We employ this data

for computing consumption values for agents in the

Indian market. Since consumption in the US market

is much higher compared to that in rural India, we per-

form appropriate scaling (described in Section 4.6).

Table 3: The income and energy consumption distribution

in US households based on the RECS report (EIA, 2015).

Household Income

(USD per year)

Consumption per

Household member

(in million BTU)

< 20,000 25.9

20,000–39,999 29.3

40,000–59,999 29.9

60,000–79,999 29.9

80,000–99,999 31.5

100,000–119,999 30,6

120,000–139,999 33,7

> 140,000 36.8

4.6 Initialization

Population. We simulate trading between agents in

eight populations of size ∈ {122, 160, 204, 250, 292,

372, 667, 757} corresponding of actual village sizes.

Within each population, the agents are assigned to

Dalits or Others according to the data (Table 1).

Income. Given an agent’s population and caste, its

income range is computed according to the distribu-

tion of incomes (Table 2). Then, an income is ran-

domly selected within the computed range.

Production. Individuals produce energy based on

their disposable income since they must be able to

afford the equipment. Thus, production is computed

from income. According to a survey (ICE 360, 2016),

Indian households in the the bottom quantile spend

around 20% of their income on other expenses, which

we consider as disposable income to pay for electric-

ity production. Given that a device with a production

of 0.1kWh costs around 1,600 INR and the lifespan

of a solar panel is around 20 years, we assume house-

holds invest all disposable income for the following

20 years to buy as many devices as they can afford.

Thus, the available production is computed by multi-

plying the production of a single device by the num-

ber of devices that a household can afford, given its

disposable income for the following 20 years.

Consumption. First, we map the income of an

agent from the Indian range (0–60,000) in Table 2 to

the USA range (0–150,000) in Table 3. Then, we as-

sign an initial consumption value to the agent from

Table 3. Next, we scale the initial consumption value

based on the average consumption values (in 2015)

of Indian household, given as 806 kWh (compared to

12,984 kWh of US) (The World Bank, 2014). Yearly

SIMULTECH 2021 - 11th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications

76

consumption is then converted to daily consumption.

The energy needs of an average Indian household

and an average rural Indian household may differ.

Thus, the consumption values are further rescaled,

controlled by the consumption offset parameter ∈

{0.25, 0.5, 1.0}. Finally, for each agent, a daily con-

sumption value is sampled from a normal distribu-

tion centered on the scaled consumption value for the

agent, and having a standard deviation controlled by

the consumption std.dev parameter ∈ {10, 50}.

Discrimination. In a bilateral market, the parame-

ter fraction of O discriminating D ∈ {0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8,

1} controls the number of agents in O that discrimi-

nate the agents in D (one direction). A discriminating

agent in O refuses to buy from an agent in D, if paired

so by the protocol, with a high probability (90%).

In a mediated market, the same parameter (fraction

of O discriminating D ∈ {0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1}) controls

the percentage of inter-caste trades (in either direc-

tion) that the mediator allows.

4.7 Submodels

Listing 1 describes the three protocols introduced in

Section 4.4. The full surplus protocol is a baseline,

representing how batteries are likely traded in a phys-

ical market. The bid splitting and multibidding proto-

cols capture the mechanisms we introduce.

Each protocol starts by sorting the bids. The sort-

ing order makes a difference during partner selection

(Listing 2). In the full surplus protocol, both sellers’

and buyers’ bids are sorted in the descending order.

This captures the intuition that a seller wants to sell

his or her battery to a buyer with the highest possi-

ble demand but less than the seller’s surplus. In con-

trast, the other two protocols sort the sellers’ bids in

descending order and buyers’ bids in ascending order

giving priority to sellers with higher surplus and buy-

ers with lower demand. However, since the trade hap-

pens with split bids in bid splitting and multibidding

protocols, all agents get an opportunity to trade.

The simulation is implemented in Python 3 based

on the MESA simulation framework

1

with custom-

made agents and actors. The source code is available

on GitHub

2

. The simulation was executed on a work-

station with 48 cores and 64GB of RAM.

1

https://github.com/projectmesa/mesa

2

https://github.com/bennati/EnergyVCG/tree/

discrimination_dev

Listing 1: Trading protocols.

1: procedure FULL_SURPLUS_PROTOCOL(S, B)

2: SORT_BIDS(S,‘DSC’, B, ‘DSC’)

3: TRADE(S, B);

4: return MEASUREMENTS()

5: procedure BID_SPLITTING_PROTOCOL(S, B)

6: SORT_BIDS(S, ‘DSC’, B, ‘ASC’)

7: SPLIT_BIDS(S, B)

8: TRADE(S, B)

9: return MEASUREMENTS()

10: procedure MULTIBIDDING_PROTOCOL(S, B)

11: SORT_BIDS(S, ‘DSC’, B, ‘ASC’)

12: while ¬(S.BIDS().EMPTY()

|| B.BIDS().EMPTY()) do

13: SPLIT_BIDS(S, B)

14: TRADE(S, B)

15: return MEASUREMENTS()

16: procedure TRADE(S, B)

17: partners_list ←

/

0

18: next_partners ← SELECT_PARTNERS(S, B)

19: while next_partners 6=

/

0 do

20: partners_list.ADD(next_partners)

21: next_partners ← SELECT_PARTNERS(S, B)

22: for all partners ∈ partners_list do

23: PERFORM_TRADE(partners[0], partners[1])

24: UPDATE_BIDS(S, B)

5 EXPERIMENTS

We evaluate the following hypotheses.

H

1

: Discrimination prevents Dalits from accessing

the market, hence reducing θ

D

.

H

2

: Discrimination reduces market efficiency γ.

H

3

: In a mediated market, implemented with a dis-

criminating mediator, the efficiency γ as well as the

satisfaction of both Dalits η

D

and Others η

O

, will

be worse than in the non-mediated case.

H

4

: The bid-splitting strategy increases the effi-

ciency of trade γ even if discrimination occurs.

H

5

: Given H3 and H4, bid splitting increases the

range of situations in which a mediated configu-

ration is preferable, for efficiency γ and η

D

, over a

bilateral configuration.

H

6

: In the condition that total surplus is larger than

total demand: S

D

+ S

O

> C

D

+ C

O

, where there is

the possibility of satisfying the needs in the mar-

ket completely, discrimination prevents trade T

O

D

,

which might reduce the demand satisfaction η

O

.

Simulations were run for 10 trading days, for each

combination of population size ∈ {122, 160, 204, 250,

292, 372, 667, 757}, consumption offset ∈ {0.25, 0.5,

Discrimination between Social Groups: The Influence of Inclusiveness-Enhancing Mechanisms on Trade

77

Listing 2: Bid splitting and Partner selection.

1: procedure SPLIT_BIDS(S, B)

2: all_bids ← S.BIDS() ∪ B.BIDS()

3: max_chunk_size ← MINIMUM(all_bids)

4: for all s ∈ S do

5: s.split_bids ← SPLIT(s.bid, max_chunk_size)

6: for all b ∈ B do

7: b.split_bids ← SPLIT(b.bid, max_chunk_size)

8: procedure SELECT_PARTNERS(S, B)

9: while i < S.LENGTH() do

10: while j < B.LENGTH() do

11: if protocol == ‘Full_Surplus’ then

12: match_condition ← S[i].bid >= B[ j].bid

13: else

14: match_condition ←

S[i].split_bids[0] == B[ j].split_bids[0]

15: if match_condition == True then

16: if DISCRIMINATES(S[i], B[ j]) == True then

17: i ← i + 1 Discriminating seller

18: else if DISCRIMINATES(B[i], S[ j]) == True then

19: j ← j + 1 Discriminating buyer

20: else

21: return hi, ji No discrimination

22: j ← j + 1

23: i ← i + 1

24: return

/

0

1.0}, consumption std.dev ∈ {10, 50}, and fraction of

O discriminating D ∈ {0.0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0}, result-

ing in in 240 samples, with 10 replications each.

First, we analyze the sensitivity of important ob-

servable variables (market efficiency γ and market ac-

cess for Dalits with production surplus θ

D

) to varia-

tion of the control variables above. In this analysis, a

market is assumed with bilateral trade among agents

using FULL_SURPLUS protocol. The sensitivity anal-

ysis is used to configure the following experiments.

Experiment 1: compares the efficiency and satisfac-

tion in bilateral markets, for varying discrimina-

tion by agents, in markets with different transaction

types (H

1

and H

2

).

Experiment 2: compares the efficiency and satisfac-

tion of a bilateral and a mediated configuration,

with and without bid splitting, against discrimina-

tion (H

3

, H

4

, and H

5

).

Experiment 3: compares the reduction of satisfac-

tion factors by discrimination (in particular, the

slope in demand satisfaction) in cases with surplus

production with that in cases with shortage, both

in bilateral and mediated markets (H

6

).

6 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

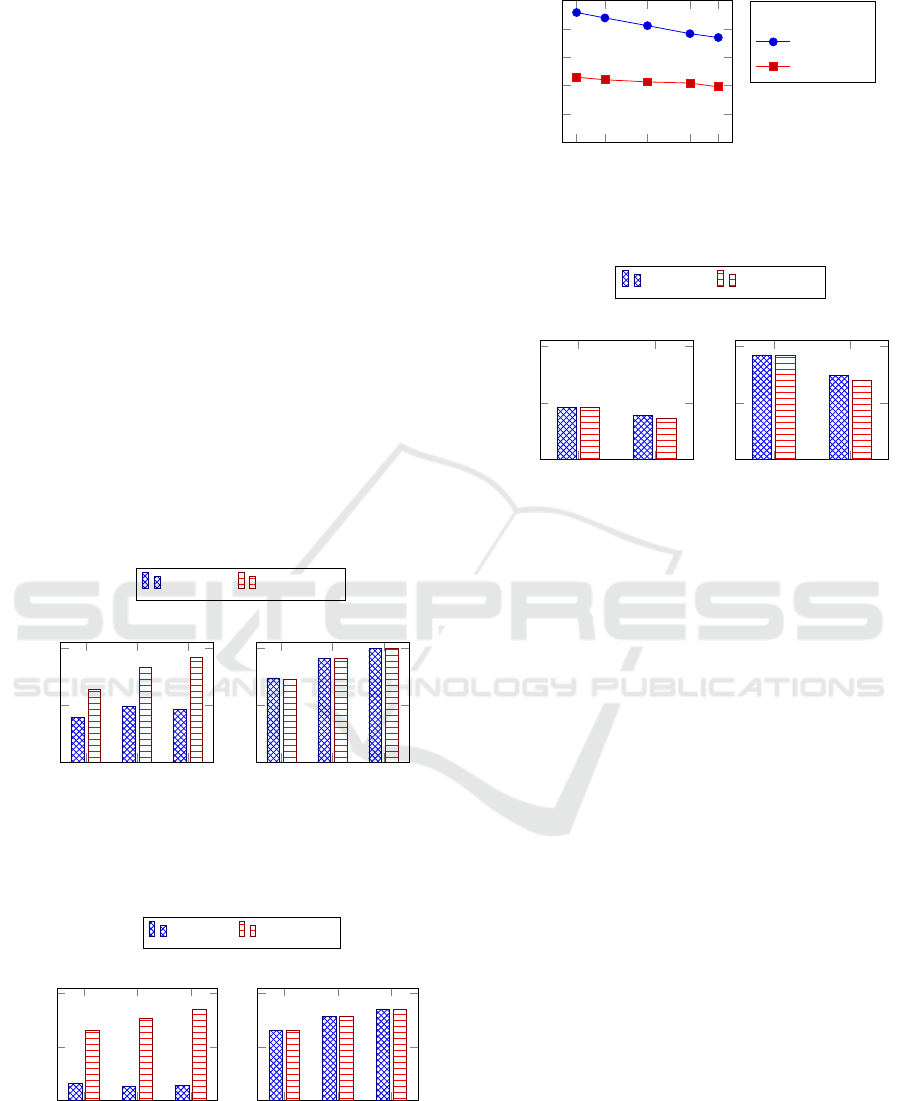

Sensitivity Analysis. The average γ and θ

D

values

from 2400 observations were 0.687 and 0.372, respec-

tively. Average within-sample variance resulting from

random generation processes in the simulations was

5% and 14% of total variance for γ and θ

D

, respec-

tively, leaving the rest to be explained from parameter

variations. Table 4 shows the results of multiple re-

gression to test sensitivity, with adjusted R

2

values of

0.76 and 0.74, respectively.

Table 4: Regression coefficients from sensitivity analysis.

Estimate Std.Error Pr(> |t|)

Coefficients for γ:

(Intercept) 1.272 8.2e-3 <2e-16

Fraction of

O discriminating D

-0.095 5.1e-3 <2e-16

Consumption offset -8.024 0.109 <2e-16

Consumption std.dev. -9.5e-3 2e-4 <2e-16

Population size -5e-6 8.5e-6 0.559

Consumption offset

× std.dev.

0.124 3e-3 <2e-16

Coefficients for θ

D

:

(Intercept) 0.126 0.01 <2e-16

Fraction of

O discriminating D

-0.295 6.4e-3 <2e-16

Consumption offset 4.708 0.135 <2e-16

Consumption std.dev. 5e-3 2.5e-4 <2e-16

Population size -1.7e-5 1.1e-5 0.0992

Consumption offset

× std.dev.

-0.014 3.8e-3 0.0002

Discrimination and consumption distribution have

strong and significant effects on the simulation out-

comes. Thus, in testing hypotheses, we differenti-

ate the variable analyzed with respect to the values

of these two parameters.

Population size has no relevant effect. ANOVA

with Tukey test did not reveal significant differences

between average outcomes for different population

sizes. Since larger population sizes have negligible

effects and largely affect simulation time, we perform

further experiments on populations of 100 agents.

For hypothesis testing, we formed a dataset, con-

taining results from 10 replications of simulations

of 10 trading days. Each replication freshly gener-

ated random variables for each of the possible com-

binations of discrimination (5 values as above), con-

sumption distribution characteristics (6 combinations

as above), market type ∈ {bilateral, mediated}, and

transaction type ∈ {full daily surplus, bid split, multi-

bid}, resulting in 18000 observations.

SIMULTECH 2021 - 11th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications

78

6.1 H

1

(Market Access)

Figure 3 shows the market access for Dalits, averaged

over the transaction types, for the different consump-

tion distributions. In all cases, the effect of discrimi-

nation on θ

D

is significant (p <0.001). Figure 4 shows

the market access for Dalits for each transaction type,

averaged over different consumption characteristics,

for different discrimination levels. Again, the dif-

ference, across discrimination levels, was significant

(p <0.001). These results confirm that discrimination

reduces the market access for Dalits (H

1

).

(0.025, 10)

(0.025, 50)

(0.05, 10)

(0.05, 50)

(0.1, 10)

(0.1, 50)

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Consumption parameters

θ

D

Discrimination=False

(0.025, 10)

(0.025, 50)

(0.05, 10)

(0.05, 50)

(0.1, 10)

(0.1, 50)

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Consumption parameters

Discrimination=True

Bilateral Mediated

Figure 3: Average θ

D

values for different consumption dis-

tribution parameters (offset, SD) in non-discriminating and

discriminating bilateral and mediated trades.

Further, with no discrimination (Figure 3, left),

simulated results did not significantly differ between

bilateral and mediated trading. However, with dis-

crimination (Figure 3, right), for the right most con-

sumption configuration, the difference in θ

D

between

bilateral and mediated markets was significant, show-

ing that a discriminating mediator, segregating the

market, can further influence θ

D

.

Finally, transaction type had little effect on the

market access for Dalits in both bilateral and medi-

ated markets. Figure 4 shows the result for bilateral

case (results for the mediated case are similar).

0 0.2

0.5

0.8 1

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Discrimination

θ

D

Transaction

Full

Bid splitting

Multibid

Figure 4: Average effect from fraction of O discriminating

D on θ

D

, under different transaction types in bilateral trade.

6.2 H

2

(Market Efficiency)

Figure 5 shows the effect of discrimination on mar-

ket efficiency (averaged across consumption distribu-

tions) for different transaction types. The effect of

discrimination on market efficiency was significant

(p < 0.001), confirming H

2

. Further, we observe that

the difference in efficiency between transaction types

was also significant (p < 0.001). These results are for

the bilateral market. Similar results are obtained for

mediated markets (Section 6.3).

0 0.2

0.5

0.8 1

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Discrimination

γ

Transaction

Full

Bid splitting

Multibid

Figure 5: Average effect of discrimination on market effi-

ciency γ under different transaction types in bilateral trade.

6.3 H

3

(Discriminating Mediator)

Since a discriminating mediator may separate the

markets for Dalits and Others, not all trade oppor-

tunities can be utilized, which can potentially lower

market efficiency and demand satisfaction (H

3

).

Figure 6 shows the effect of discrimination on ef-

ficiency and demand satisfaction in a mediated mar-

ket. The differences were significant (p < 0.001),

confirming H

3

. Further, it is interesting to observe

that, discrimination reduces the demand satisfaction

for not only the Dalits (η

D

) but also the Others (η

O

).

However, the margin of difference is much higher for

the Dalits than the Others.

γ

η

O

η

D

0

0.5

1

Discrimination=False

γ

η

O

η

D

0

0.5

1

Discrimination=True

Full Bid splitting Multibid

Figure 6: Average values of efficiency (γ), demand satisfac-

tion of Others (η

O

) and Dalits (η

D

) in a mediated market

with a non-discriminating and a discriminating mediator.

Discrimination between Social Groups: The Influence of Inclusiveness-Enhancing Mechanisms on Trade

79

6.4 H

4

(Bid Splitting)

Bid splitting, i.e., selling the daily surplus in fixed

chunks, as well as the multibid market with variable

chunks, increases efficiency in bilateral and mediated

markets, with and without discrimination, as Figures

5 and 6 show, confirming H

4

.

6.5 H

5

(Bid Splitting and Mediation)

Given H

4

results, it is tempting to assume that it

would be preferable to implement a mediated system

with some bid-splitting mechanism, even if discrimi-

nation is possible. However, as Figures 7 and 8 show,

this is not the case. That is, if there is discrimination,

(1) the efficiency (Figure 7) of the mediated market is

worse than that of the bilateral market; and

(2) the demand satisfaction of Dalits (Figures 8) is

worse (to a greater degree than efficiency) in the

mediated market than in the bilateral market.

Thus, we could not confirm H

5

. In essence, we

observe that a discriminating mediator is worse than

a bilateral market with discrimination.

Full

Bid-splitting

Multibid

0

0.5

1

γ

Discrimination=True

Full

Bid-splitting

Multibid

0

0.5

1

Discrimination=False

Bilateral Mediated

Figure 7: Market efficiency (γ), without and with discrimi-

nation, in mediated and bilateral markets.

Full

Bid-splitting

Multibid

0

0.5

1

η

D

Discrimination=True

Full

Bid-splitting

Multibid

0

0.5

1

Discrimination=False

Bilateral Mediated

Figure 8: Demand satisfaction for Dalits (η

D

), without and

with discrimination, in mediated and bilateral markets.

0 0.2

0.5

0.8 1

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Discrimination

η

O

Production

Surplus

Shortage

Figure 9: Effect of discrimination on η

O

in bilateral trade,

in situations of surplus production and shortage.

False

True

0

0.5

1

Discrimination

η

O

Production=Shortage

False

True

0

0.5

1

Discrimination

Production=Surplus

Bilateral Mediated

Figure 10: Effect of discrimination on Others’ demand sat-

isfaction (η

O

) in bilateral and mediated markets.

6.6 H

6

(Demand Satisfaction)

The preceding hypotheses were mainly about the neg-

ative effects on Dalits. However, in some cases, dis-

crimination may also affect the discriminating Others.

Complete demand fulfillment is possible if the to-

tal surplus production from the entire population ex-

ceeds the total demand, with some margin for chunk

size ε, i.e., η

O

= 1 − ε. However, when Others refuse

to buy from Dalits, possible fulfillment cannot not be

realized in some cases, resulting in a discrimination-

induced reduction of η

O

. Figures 9 and 10 show this

effect. The effect of discrimination on η

O

was signif-

icant (p < 0.001) in both shortage and surplus cases,

confirming H

6

. However, we observe that this effect

is stronger with a surplus as opposed to shortage.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Discrimination has an Overall Negative Effect on

Market. Our simulation confirms the negative effect

of discrimination in prosumer markets in terms of re-

duced trade efficiency (H

2

) and, in particular, reduced

market access for the discriminated group (H

1

). We

show how discrimination can damage the discriminat-

ing group as well. By restricting market access of the

discriminated group and with it the overall trade vol-

SIMULTECH 2021 - 11th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications

80

ume, the demand satisfaction of both discriminated

and discriminating groups are affected.

Increasing Production May Not Reduce

Discrimination. We show that discrimination

prevents complete demand satisfaction even when

production is surplus (H

6

). Thus, subsidies for the

purchase of equipment, so as to increase production

capacity, especially, that of the discriminated group,

would not solve the problem. On the contrary, their

positive effect would be eroded by discrimination.

Mediation with Discrimination is Worse than

Bilateral Trade. Some people may have regular over-

production and some regularly suffer from shortage,

instigating trading opportunity. As long as no elec-

tricity grid is in place, surplus energy will have to be

stored in and traded via batteries. On the one hand,

bilateral trade, requiring physical contact, is subject

to discrimination. On the other hand, mediation in-

creases personal distance and can potentially reduce

discrimination. However, we show that, a mediated

market with discriminating mediator is worse than a

non-mediated market for both Dalits and Others (H

3

).

Agent-based Mediation Reduces Discrimination.

A human mediator is subject to the same prejudices

as the rest of the society. If the mediator is a Dalit, the

Others may not buy from the mediator. If the mediator

is an Other, he or she may segregate the market to con-

form to social rules. We study agent-based mediation,

where agents trade on behalf of humans. We argue

that agents designed with the values of anonymiza-

tion and inclusion reduce discrimination. We propose

a mechanism, involving bid splitting and multibid-

ding, for agents to trade energy, e.g., via a local grid.

Our overall simulation results show that the proposed

mechanism is effective in reducing discrimination.

REFERENCES

Betancourt, R. and Gleason, S. (2000). The allocation of

publicly-provided goods to rural households in India:

On some consequences of caste, religion and democ-

racy. World Development, 28(12):2169–2182.

Bhattacharyya, S. C. (2006). Energy access problem of the

poor in India: Is rural electrification a remedy? En-

ergy Policy, 34(18):3387–3397.

Borooah, V. K., Diwakar, D., Mishra, V. K., Naik, A. K.,

and Sabharwal, N. S. (2014). Caste, inequality, and

poverty in India: A re-assessment. Development Stud-

ies Research, 1(1):279–294.

Bower, J. and Bunn, D. (1999). A Model-Based Com-

parison of Pool and Bilateral Market Mechanisms for

Electricity Trading. New York, 44(0):1–20.

Bullinaria, J. (2018). Agent-based models of gender in-

equalities in career progression. Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation, 21(3):7.

Census of India (2011). Sources of lighting: 2001–

2011. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/hlo/

Data_sheet/India/Source_Lighting.pdf.

Chaurey, A. and Kandpal, T. C. (2010). A techno-economic

comparison of rural electrification based on solar

home systems and PV microgrids. Energy Policy,

38(6):3118–3129.

Chen, S. H. (2012). Varieties of agents in agent-based com-

putational economics: A historical and an interdisci-

plinary perspective. Journal of Economic Dynamics

and Control, 36(1):1–25.

Cust, J., Singh, A., and Neuhoff, K. (2007). Rural electri-

fication in India: Economic and institutional aspects

of renewables. Cambridge Working Papers in Eco-

nomics 0763, University of Cambridge.

EIA (2015). US Energy Information Administration: Res-

idential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS). https:

//www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2015/.

Accessed: September 2019.

Grimm, V., Berger, U., DeAngelis, D. L., Polhill, J. G.,

Giske, J., and Railsback, S. F. (2010). The ODD pro-

tocol: A review and first update. Ecological mod-

elling, 221(23):2760–2768.

ICE 360 (2016). People Research on India’s Consumer

Economy: How Indians Spend? http://www.ice360.

in/en/projects/homepageservey/how-indians-spends.

Accessed: September 2019.

Ilic, D., Da Silva, P. G., Karnouskos, S., and Griesemer,

M. (2012). An energy market for trading electricity

in smart grid neighbourhoods. In IEEE International

Conference on Digital Ecosystems and Technologies,

pages 1–6.

Kirman, A. (1989). The intrinsic limits of modern economic

theory: The emperor has no clothes. The Economic

Journal, 99(395):126–139.

Lee, J., Guo, J., Choi, J. K., and Zukerman, M. (2015).

Distributed Energy Trading in Microgrids: A Game

Theoretic Model and Its Equilibrium Analysis. IEEE

Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 62(6):1–1.

Li, G., Shi, J., and Qu, X. (2011). Modeling methods for

GenCo bidding strategy optimization in the liberalized

electricity spot market–a state-of-the-art review. En-

ergy, 36(8):4686–4700.

Nadal, J.-P., Chenevez, O., Weisbuch, G., and Kirman,

A. (1998). A formal approach to market organiza-

tion: Choice functions, mean field approximation and

maximum entropy principle. In Advances in Self-

Organization and Evolutionary Economics: New De-

velopments, pages 1–9.

Plous, S. (2003). The psychology of prejudice, sterotyp-

ing, and discrimination: An overview. In Plous, S.,

editor, Understanding prejudice and discrimination,

pages 3–48. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Rawal, V. and Swaminathan, M. (2011). Income inequality

and caste in village India. Review of Agrarian Studies,

1(2):108–133.

REC Limited (2019). Household electrification status (as

reported by states). https://saubhagya.gov.in.

Discrimination between Social Groups: The Influence of Inclusiveness-Enhancing Mechanisms on Trade

81

Saad, W., Han, Z., Poor, H. V., and Ba¸sar, T. (2011). A

noncooperative game for double auction-based energy

trading between PHEVs and distribution grids. In

IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Com-

munications, pages 267–272.

Sha, M. and Catalão, J. P. S. (2015). A stochastic multi-

layer agent-based model to study electricity market

participants behavior. IEEE Transactions on Power

Systems, 30(2):867–881.

Shinde, R. (2017). Institutional innovation: Case study of

sustenance of solar electrification projects in rural In-

dia: Innovating institutions with technological innova-

tions. Master’s thesis, Delft University of Technology.

Singh, A., Strating, A. T., Herrera, N. R., van Dijk, H. W.,

and Keyson, D. V. (2017). Towards an ethnography of

electrification in rural India: Social relations and val-

ues in household energy exchanges. Energy Research

& Social Science, 30:103–115.

Takács, K. and Squazzoni, F. (2015). High standards en-

hance inequality in idealized labor markets. Journal

of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 18(4):2.

The World Bank (2014). Electric power consumption (kWh

per capita). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.

USE.ELEC.KH.PC. Accessed: September 2019.

Thorat, S. and Neuman, K. S., editors (2012). Blocked

by Caste: Economic Discrimination in Modern India.

Oxford University Press, Noida, India.

Trotter, P. A. (2016). Rural electrification, electrification

inequality and democratic institutions in sub-Saharan

Africa. Energy for Sustainable Development, 34:111–

129.

Tushar, W., Zhang, J. A., Smith, D., Poor, H. V., and

Thiébaux, S. (2014). Prioritizing consumers in smart

grid: A game theoretic approach. IEEE Transactions

on Smart Grid, 5(3):1429–1438.

Urmee, T. and Md, A. (2016). Social, cultural and politi-

cal dimensions of off-grid renewable energy programs

in developing countries. Renewable Energy, 93:159–

167.

Weidlich, A. and Veit, D. (2008). A critical survey of agent-

based wholesale electricity market models. Energy

Economics, 30(4):1728–1759.

Winker, P. and Gilli, M. (2001). Indirect estimation of the

parameters of agent based models of financial mar-

kets. Computing in Economics and Finance 2001 59,

Society for Computational Economics.

SIMULTECH 2021 - 11th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications

82