How Does the Indonesian Government Communicate Food Security

during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis on Indonesia

Official Twitter Account

Dimas Subekti

1a

, Eko Priyo Purnomo

2,* b

, Lubna Salsabila

2

c

and Aqil Teguh Fathani

2

d

1

Master of Government Affairs and Administration, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta,

Brawijaya Street, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2

Master of Government Affairs and Administration, Jusuf Kalla School of Government,

Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Food Security Agency, Logistics Affairs Agency, Communication, Social Media Twitter.

Abstract: This study aims to determine communication about food security during the COVID-19 Pandemic by

Analyzing the Indonesian Government's official Twitter account. This research method uses the NVIVO 12

plus in analyzing data with chart, cluster, and word cloud analysis. This research's data source came from

the Food Security Agency Twitter accounts and the Logistics Affairs Agency. This study chose the Food

Security Agency and the Logistics Affairs Agency's Twitter social media accounts because they are

responsible for Indonesia's food security. The finding of this study, the Food Security Agency is more

dominant in discussing communication content related to agriculture, availability of foodstuffs, food needs,

and food prices compared to the Logistics Affairs Agency. Meanwhile, the Logistics Affairs Agency is

superior in communicating content about rice availability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Content is

related to one another, but the most vital link is between foodstuffs and rice availability. The Food Security

Agency and Logistics Affairs Agency's communication narrative with the Indonesian people during the

COVID-19 pandemic concerns rice, prices, food, and Indonesian farmers. The Logistics Affairs Agency has

a higher communication intensity than the Food Security Agency with the Indonesian people in early 2020

to March 2021 period.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2452-7731

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4840-1650

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1140-9349

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0738-2916

1 INTRODUCTION

The Indonesian state has two institutions related to

national food security: the Food Security Agency

under the Ministry of Agriculture and the Logistics

Affairs Agency. This study aims to determine food

security communication during the COVID-19

Pandemic by Analyzing the Food Security Agency

and the Logistics Affairs Agency Twitter account.

The Food Security Agency (BKP) and the Logistics

Affairs Agency (Bulog) are public institutions

responsible for managing Indonesia's food security.

Therefore, disclosure of the information is a must

for public institutions to be provided to the public.

Twitter is one of the Government's facilities because

it allows communication and interaction with the

community. Twitter is a Microblogging service that

allows for a significant increase in exchange.

Efficient cognitions can be activated through Twitter

interaction (Fischer & Reuber, 2011). The Twitter

community created global social networks to send or

receive short messages in real-time (Latonero &

Shklovski, 2011). Twitter is similar to chat rooms in

that it uses the at-sign to allow users to communicate

with one another. (Murthy, 2012). This research is

also interesting for the world community because

food security during the COVID-19 pandemic is

significant. More than that, the Government's ability

Subekti, D., Purnomo, E., Salsabila, L. and Fathani, A.

How Does the Indonesian Government Communicate Food Security during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis on Indonesia Official Twitter Account.

DOI: 10.5220/0010600400003058

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2021), pages 219-226

ISBN: 978-989-758-536-4; ISSN: 2184-3252

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

219

to communicate about the food situation in their

country is a way to avoid public panic.

The problem during the COVID-19 pandemic

was its impact on all lines of life, including the

economic side of the Indonesian people, including

the fulfillment of basic needs. Rice is the main food

commodity for the people of Indonesia, so it plays a

significant role. Rice is also used as a raw material

in vermicelli, cakes, instant rice flour, and others

(Mentang, Liando, & Lengkong, 2017). Therefore,

through the Food Security Agency and the Logistics

Affairs Agency, the Government needs to ensure

adequate food stocks and explain the situation to the

Indonesian people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted Indonesia's

economy, as evidenced by Indonesia's economic

growth, which is estimated to only grow 2.5 percent

from ordinary, capable of up to 5.02 percent(Fahrika

& Roy, 2020). COVID-19 can have an impact on

decreasing socioeconomic behavior and decreasing

people's income. There is a strong link between the

pandemic that has tested positive for COVID-19, the

death rate, and socioeconomic conditions(Prawoto,

Purnomo, & Zahra, 2020).

In some countries that are still developing, the

COVID-19 pandemic tends to cause food insecurity.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has

severely limited food supply and access. This will

affect economic slowdown and increase

poverty(Udmale, Pal, Szabo, Pramanik, & Large,

2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has caused

widespread disruptions, placing billions of people's

food security in danger. Food supply disruptions

caused by the pandemic could double global hunger,

especially in Africa and developing countries

(Zurayk, 2020; Purnomo et al., 2021).

Therefore, this research focuses on the

communication carried out by state institutions in

charge of food security to the public during the

COVID-19 pandemic via Twitter. This research will

answer how the Food Security Agency and the

Logistics Affairs Agency communicate about food

security on Twitter during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The limitation of this study is that it only uses one

type of Twitter.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Social Media in Government

Social media is a virtual environment where people

can exchange knowledge and ideas and collaborate

to form new notions(Malawani, Nurmandi,

Purnomo, & Rahman, 2020). According to Costa

(2018), as a medium for public communication with

a practical monitoring framework, social media is

becoming increasingly popular(Purnomo et al.,

2021). In recent years, government agencies have

embraced various Web 2.0 tools, like blogs, wikis,

social networking, microblogging, visualization

apps, multimedia sharing, tagging, crowdsourcing,

and virtual worlds. The increasing use of social

media in Government is now aimed at transforming

how government bureaucracies function internally

and interact with the public outside of their

walls(Criado, Sandoval-Almazan, & Gil-Garcia,

2013). Fostering social media in Government has

aimed to enhance citizen experiences in near-real-

time, transform government attitudes and behaviors

in knowledge exchange and service provision, alter

government decision-making habits, and force

policy changes based on common citizen

feedback(Chun & Luna Reyes, 2012). The

development of social media tools has changed

modes of communication between governments and

citizens in discussing daily issues. Those

communications also opened up opportunities for

greater political participation, leading to a new

social dynamic(Nurmandi et al., 2018). Social media

tools can exchange information with the public and

reach into the public's collective ingenuity to support

the Government in achieving its goals. While social

media can help a government agency save cash, its

true strength is in increasing audience engagement,

which helps that agency's mission(Dadashzadeh,

2010).

Government science agencies use social media

to disseminate information produced by the

agencies, suggesting a dedication to deficit-model

thinking and little need for dialogic strategies(Lee &

VanDyke, 2015). Governments turn to social media

to provide new channels for information

dissemination, communication, and participation,

enabling citizens to interact with government

officials and make excellent decisions(Song & Lee,

2016). In Government, social media provides a

quick and transparent method of disseminating

information that can be customized to offer

programs that include public participation(Budiana,

H. R., Sjoraida, D. F., Mariana, D., & Priyatna,

2016). Technology competence, top management

support, citizen readiness, and perceived benefits all

play a role in government agencies' social media

usage (Hui Zhang, 2017).

WEBIST 2021 - 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

220

2.2 Food Security in Pandemic

Covid-19

The term "food security" was coined in the early

1970s as a concept of food supply in reaction to

concerns that a global food shortage would endanger

political stability (Jones, Ngure, Pelto, & Young,

2013). Food security means that all people have

access at any time to get sufficient food and the

conditions necessary for a population to be healthy

and well-nourished (Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt,

Gregory, & Singh, 2019). Two broad perspectives

on food security have been identified. One that

focused on growing product as the critical approach

to under-consumption and hunger. The other is a

new social and ecological perspective that

recognizes the need to address various issues, not

just production (Lang & Barling, 2012)—as per

some, ensuring food security is an integrated task

that involves agriculture, political will, and product

delivery logistics (Prosekov & Ivanova, 2018).

COVID-19 is causing havoc on food supply

chains at all levels, from local to global, in a way

that our global society has never seen before.

Chronic food insecurity and a food crisis result from

the cascading effects of Covid-19 (Udmale et al.,

2020; Setiawana et al., 2021). A significant indirect

consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic spreading

across the Global South is a dramatic rise in hunger

and food insecurity. The FAO (Food and Agriculture

Organization) United Nations' (2020) has marked

the food security consequences a crisis within a

crisis, while the World Food Program has labeled it

a hunger pandemic, warning that 30 million people

could die of starvation (Crush & Si, 2020). More

than half of respondents in Kenya during the

COVID-19 period were concerned about food

shortages, and we're unable to eat safe and nutritious

food, ate smaller portions, and ate a limited variety

of foods. Similarly, compared to the usual time, the

number of Ugandans who decreased their food

consumption could not eat safe and nutritious food,

ate less varied diets or were concerned about

running out of food increased significantly during

the COVID-19 era (Kansiime et al., 2021; Ramdani

et al., 2021).

Global hunger is another tragedy that comes

with the COVID-19 pandemic. The director of the

World Food Program warned in April 2020 that the

coronavirus could bring another 130 million people

to the brink of starvation by the end of the year.

This number will increase the number of food-

insecure people globally, which currently reaches

821 million people (Moseley & Battersby, 2020;

The Phan et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic is

unprecedented, with social and economic

consequences. As a result of the COVID-19

pandemic, there have been school closures, appeals

to stay at home, business closures, many people

have lost their jobs, and so on. This phenomenon

has an impact on the potential for a significant

increase in food insecurity. Food insecurity appears

to be rapidly rising above pre-epidemic levels,

according to preliminary evidence. Food insecurity

among households increased from 11% in 2018 to

38% in March 2020; 35% of families with children

aged 18 and under were food insecure in April

2020 (Wolfson & Leung, 2020).

3 METHODS

This research method uses NVIVO 12 plus

analyzing data with chart, cluster, and word cloud

analysis. NVIVO 12 plus is a Computer Assisted

Qualitative Data Analysis Software. NVIVO 12 plus

aims to facilitate qualitative research to be more

effective and efficient in analyzing data. Using the

NVIVO 12 plus method is N-capture the Twitter

account of the food security agency and the logistics

affairs agency. Then the download is inputted into

the NVIVO 12 plus. Next, enter the downloaded

results into the chart, cluster, and word cloud

features on the NVIVO 12 plus, which aims to

analyze and display data.

This research's data source came from the

Twitter accounts of the Food Security Agency and

the Logistics Affairs Agency. This study chose the

Food Security Agency and the Logistics Affairs

Agency's Twitter accounts because these two

institutions are responsible for food security in

Indonesia. The data collection period on the Food

Security Agency and Logistics Affairs Agency

Twitter accounts ranges from January 2020 to March

2021. During that period, Indonesia was hit by the

Covid-19 pandemic, which disrupted the economic

side of the community. Data is taken from the

Twitter accounts of the Food Security Agency and

the Logistics Affairs Agency in the form of

followers, following, tweets, retweets, followers,

following communication content, communication

narratives, and communication intensity.

The number of tweets on the Food Security

Agency Twitter account reached 971. Furthermore,

the number of retweets on the Food Security Agency

social media accounts was 2211 Figure 1.

How Does the Indonesian Government Communicate Food Security during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis on Indonesia

Official Twitter Account

221

Figure 1: Tweet and retweet the Food Security Agency

and the Logistics Affairs Agency Twitter Account.

Meanwhile, the number of tweets of the Logistics

Affairs Agency Twitter accounts was 2698.

Furthermore, there were only 542 retweets of the

Logistics Affairs Agency Twitter accounts Figure 1.

The Food Security Agency Twitter account has

4,391 followers and 80 following. Meanwhile, the

Twitter Logistics Affairs Agency social media

account has 7,386 followers and 312 following. The

number of tweets, retweets, followers, and following

the Twitter accounts of the Food Security Agency

Twitter and the Logistics Affairs Agency shows that

the Twitter account is active.

4 FINDING AND DISCUSSION

4.1 The Communication Content on

Twitter

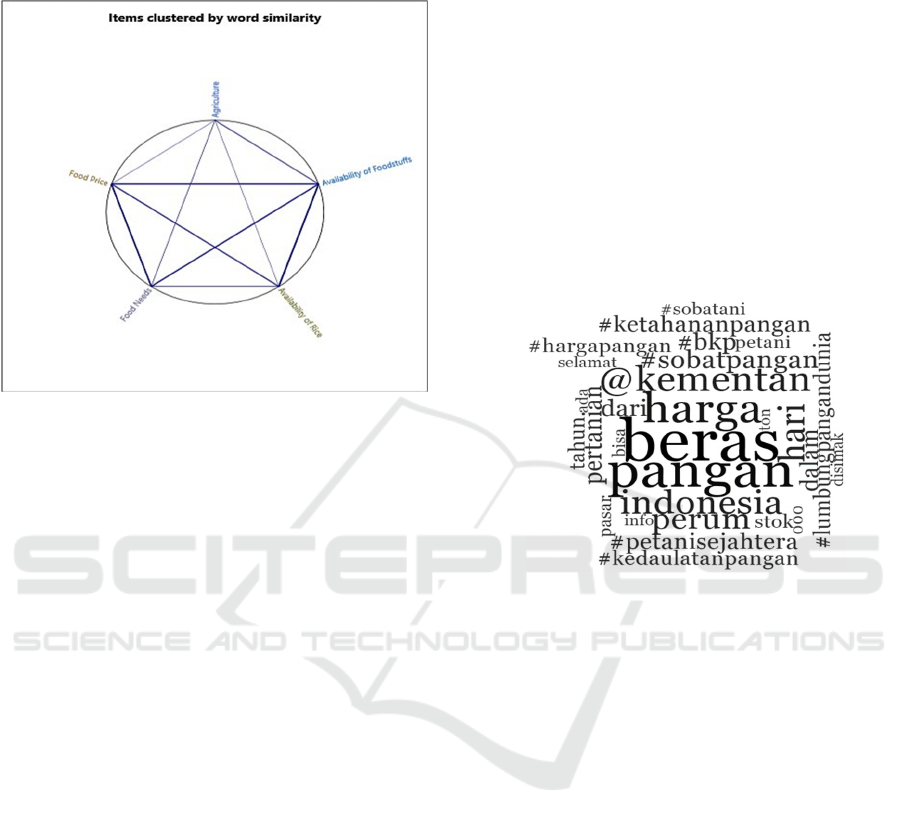

The Food Security Agency and Logistics Affairs

Agency use Twitter to communicate with the

Indonesian public regarding food security content.

The chart analysis Figure 2 shows the Food Security

Agency's communication content and the Logistics

Affairs Agency on Twitter. Chart analysis of Figure

2 helps to understand how the Food Security

Agency's communication content and the Logistics

Affairs Agency related to food security during the

COVID-19 period. The chart analysis results in

figure 2 are processed by auto-code files captured by

the Twitter accounts of the food security agency and

the logistics affairs agency using NVIVO 12 plus.

after that, sort out the content discussed on the

Twitter account. Then the content is entered into the

chart analysis feature on the NVIVO 12 plus to

process and display the data.

Based on Figure 2, the Food Security Agency's

communication content in discussing agriculture is

96.51%, while the Logistics Affairs Agency

communicates content about agriculture only at

Figure 2: Communication Content of Food Security

Agency and Logistics Affairs Agency based on Twitter.

3.49%. The Food Security Agency looks significant

in communicating about agriculture compared to the

Logistics Affairs Agency because it is under the

Ministry of Agriculture, which incidentally deals

with Indonesia's agricultural issues. Furthermore, the

Food Security Agency's communication content on

the availability of foodstuffs was 60.38%, compared

to the Logistics Affairs Agency, which also

discussed content on the availability of foodstuffs of

39.62%. The Food Security Agency appears to be

more dominant in communicating content about

foodstuffs' availability on Twitter than the Logistics

Agency. This is inseparable from the duties and

functions of the Food Security Agency, one of which

is responsible for coordination, assessment, policy

formulation, monitoring, and consolidation in the

field of foodstuffs availability (Bkp.pertanian,

2021).

The Food Security Agency's communication

content regarding rice availability was only 36.76%,

and the Logistics Affairs Agency communicated

content about the availability of rice on Twitter at

63.24%. This is in line with the Logistics Affairs

Agency's primary duties, responsible for rice

management in Indonesia. The Food Security

Agency also communicates content about food

needs of 63.62%, while the Logistics Affairs Agency

talks about it on Twitter at 36.38%. Finally, talking

about the content of food prices, the Food Security

Agency communicated on Twitter at 66.18%

compared to the Logistics Affairs Agency at

33.82%.

The Food Security Agency and Logistics

Affairs Agency's communication content on

Twitter is agriculture, availability of foodstuffs,

availability of rice, food needs, and food prices.

Communication content has a relationship with

each other. Figure 3 results from the Cluster

971

2211

2698

542

Tweet

Retweet

0 2000 4000

The Logistics

Affairs Agency

Food Security

Agency

WEBIST 2021 - 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

222

Analysis, which shows the connectivity between

the communication content.

Figure 3: The relationship between Communication

Content Food Security Agency and Logistics Affairs

Agency based on Twitter.

Based on Figure 3, the relationship between rice

availability and the availability of foodstuffs has the

highest connectivity. This is followed by a linkage

of communication content about food prices and

food needs, in the third position the relationship

between food prices and availability of foodstuffs.

The fourth is the relationship between food needs

and the availability of foodstuffs, and the fifth is the

relationship between food prices and rice

availability—Furthermore, the relationship between

the availability of foodstuffs and agriculture. The

seventh relationship is between the communication

content of food needs and the availability of rice.

Eight relationships between food needs and

agriculture, followed by the relationship between

rice and agriculture availability. Finally, the weakest

link in the content of food price communication with

agriculture.

4.2 The Communication Narrative on

Twitter

Communication narrative Food Security Agency and

Logistics Affairs Agency is obtained from word

cloud analysis in NVIVO on the word frequency

feature. The results of word cloud analysis in figure

4 from Food Security Agency and Logistics Affairs

Agency Twitter accounts, the two institutions often

discuss narrative around food during the COVID-19

pandemic. Figure 4 shows the narrative of the

conversation on the Food Security Agency and

Logistics Affairs Agency Twitter accounts during

the COVID-19 pandemic. "beras (rice)", "pangan

(food)", "harga (price)", @kementan, "Indonesia",

#ketahananpangan(#foodsecurity),#kedaulatanpanga

n(#foodsovereignty),

#petanisejahtera(#prosperousfarmer),

#sobatpangan(#foodbuddy),

#hargapangan(#foodprice),

#lumbungpangandunia(#worldfoodbarn),

#sobattani(#farmerfriend), "pertanian(agriculture)",

"stok(stock)", "pasar(market)" are some of the words

that are often discussed in the narrative of the

conversation on the Twitter accounts of the Food

Security Agency and Logistics Affairs Agency.

Figure 4: Food Security Agency and Logistics Affairs

Agency Communication Narrative based on Twitter.

Based on figure 7, the Food Security Agency and

Logistics Affairs Agency has consistently discussed

narratives about food needs, as evidenced by the

emergence of "beras" and "pangan." The Food

Security Agency and Logistics Affairs Agency also

discussed the issue of "harga," "pasar,"

#hargapangan, and "stok" as an effort to

communicate price stability and food availability

during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Food Security

Agency and Logistics Affairs Agency emphasizes

Indonesia's food security through #ketahananpangan,

#lumbungpangandunia, #sobatpangan, "pertanian"

and #kedaulatanpangan. Interestingly, the Food

Security Agency and Logistics Affairs Agency also

invite attention to the fate of Indonesian farmers

#petanisejahtera, #sobattani, and #bkppetani. The

food security agency with the logistics affairs

agency also cooperates with other food institutions,

as seen in @kementan. @kementan is the Twitter

account of the Ministry of Agriculture of the

Republic of Indonesia.

How Does the Indonesian Government Communicate Food Security during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis on Indonesia

Official Twitter Account

223

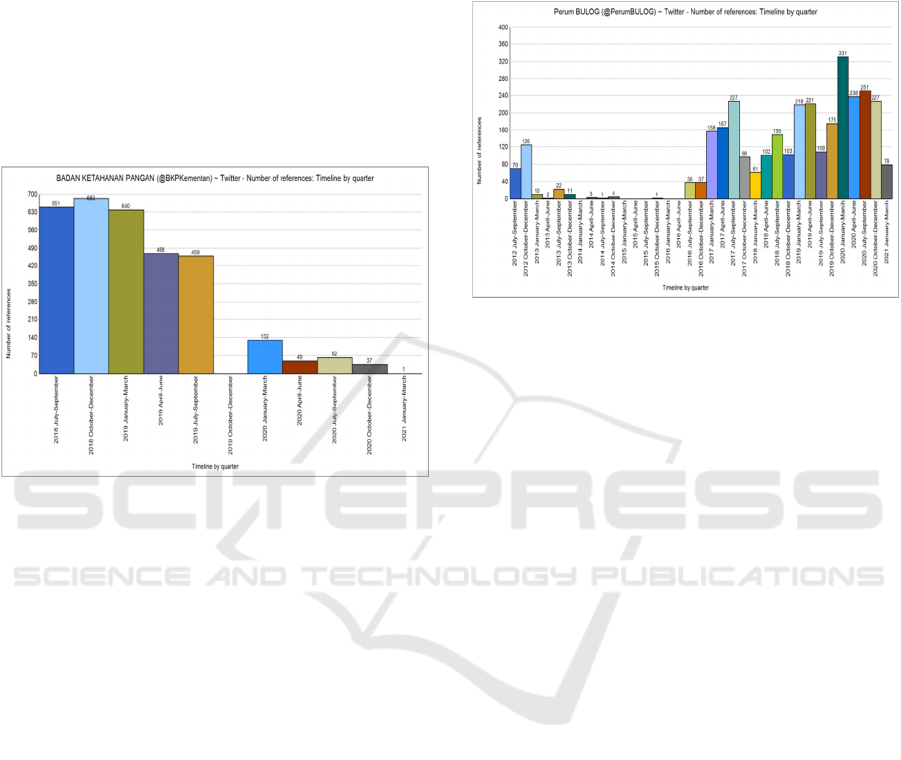

4.3 The Communication Intensity on

Twitter

The Food Security Agency responds to food security

during the COVID-19 pandemic in January-March

2020, decreasing in April-June. It increased again in

July-September 2020 but decreased again in

October-December 2020 and January-March 2021.

Figure 8 shows the complete results, the intensity of

the Food Security Agency's communication on

Twitter for January 2020-March 2021 is relatively

low compared to 2018 and 2019.

Figure 5: Food Security Agency Communication Intensity

based on Twitter.

Even so, the communication intensity of the Food

Security Agency in the July-September 2020 period

increased slightly. This is inseparable from President

Joko Widodo's appeal to his subordinates to continue

to monitor the stock and price stability of necessities.

After the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

warned that the world would experience a food crisis

at the end of August 2020 due to the spread of

COVID-19, which is uncertain when it will end

(Amalia, 2020). Food security agency communication

intensity is very low on Twitter. Therefore, food

security agencies should focus on intensifying

communication through Twitter amidst the COVID-

19 pandemic. This is useful for the Indonesian people

in obtaining information related to the state of food.

So that panic about the shortage of staple foods does

not occur in the community.

Meanwhile, the Logistics Affairs Agency

responds to food security during the COVID-19

pandemic with high communication intensity. Figure

6 shows the intensity of the Logistics Affairs

Agency's communication on Twitter in the last ten

years. The highest communication intensity of the

Logistics Affairs Agency on Twitter occurred in the

period January-March 2020. It slightly decreased in

April-June 2020, then stabilized in the period July-

September 2020 and October-December 2020.

January-March 2021 was the agency's lowest

communication intensity, Logistics Affairs Agency,

during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6: Logistics Affairs Agency Communication

Intensity based on Twitter.

Figure 6 shows that the January-March 2020

period was the highest intensity of Logistics Affairs

Agency communication. At that time, the lockdown

issue was hotly discussed by the public and the

Indonesian Government as one of the policies to

prevent the spread of Covid-19. As a result, many

questioned whether or not the supply of necessities,

including rice stocks from the Logistics Affairs

Agency, was sufficient. The Logistics Affairs

Agency Director of Operations and Public Services,

Tri Wahyudi Saleh, emphasized that the rice stock in

the Logistics Affairs Agency warehouse was still

relatively safe and could be sufficient for routine

distribution needs and market operations until the

end of 2020 (Idris, 2020). Even so, in the April-June

period, it experienced a slight decrease from the

previous one, but the intensity was still relatively

high.

Meanwhile, the July-September and October-

December periods experienced stability in terms of

communication intensity. During this period, the

Logistics Affair Agency was busy with rice

production, which had decreased compared to the

previous two years. This is due to the dry season

experienced by 30 percent of agricultural areas.

Moreover, changes in rice fields' function, which

impact threats to food security, poverty of farmers,

and ecological damage in rural areas, are also

supporting factors. Therefore, the Logistics Affairs

Agency and the Government pay special attention to

rice production to fulfill rice needs until the

beginning of 2021 until entering the next harvest

season (Mursid, 2020).

WEBIST 2021 - 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

224

5 CONCLUSION

This study's conclusions are; The Food Security

Agency is more dominant in discussing

communication content related to agriculture,

availability of foodstuffs, food needs, and food

prices compared to the Logistics Affairs Agency.

Meanwhile, the Logistics Affairs Agency is superior

in communicating rice availability to the Indonesian

people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Communication content is related to one another,

but the most vital link is between the availability of

foodstuffs and rice availability. The Food Security

Agency and the Logistics Affairs Agency's

communication narrative with the Indonesian people

during the COVID-19 pandemic is rice, prices, food,

and Indonesian farmers. The Logistics Affairs

Agency has a higher communication intensity than

the Food Security Agency with the Indonesian

people in early 2020 to March 2021 period. The

food security agency and the logistics affairs agency

have used Twitter to communicate about Indonesian

food security during the pandemic. This shows the

success of the two organizations in using social

media technology facilities as a transmitter of food

security information during the COVID-19

pandemic. This also has implications for the

responsibilities and duties of the two organizations

to the community in managing food in Indonesia

A limitation in this study is that the data source

used only comes from the Food Security Agency

and Logistics Affairs Agency's Twitter social media

accounts. Therefore, the recommendation for further

research is to take data sources from two social

media accounts, such as Facebook and Twitter, so

that the data obtained is more complete.

Advice for netizens is that more intensive

interaction with the Government's Twitter is needed.

There is reciprocity between the information

provided and the response for those who receive it.

Meanwhile, the message for the Government is

further to increase the intensity of its use of Twitter

so that it can be maximized in conveying

information.

REFERENCES

Amalia, L. S. (2020). Menanti Kebijakan Ketahanan

Pangan di Tengah Pandemi COVID-19. Retrieved

March 18, 2021, from Politik.Lipi.go.id website:

http://www.politik.lipi.go.id/kolom/kolom-2/politik-na

sional/1397-menanti-kebijakan-ketahanan-pangan-di-

tengah-pandemi-covid-19

Bkp.pertanian. (2021). Tugas Fungsi. Retrieved July 20,

2021, from bkp.pertanian.go.id website: http://bkp.per

tanian.go.id/tugas-fungsi

Budiana, H. R., Sjoraida, D. F., Mariana, D., & Priyatna,

C. C. (2016). The Use of Social Media by Bandung

City Government in Increasing Public Participation.

International Conference on Communication, Culture

and Media Studies (CCCMS, (1), 63–70. Retrieved

from http://jurnal.uii.ac.id/CCCMS/article/view/7123/

6345

Chun, S. A., & Luna Reyes, L. F. (2012). Social media in

Government. Government Information Quarterly,

29(4), 441–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.20

12.07.003

Coleman-Jensen, A., Rabbitt, M. P., Gregory, C., & Singh,

A. (2019). Household Food Security in the United

States in 2018. Economic Research Report No. 270.

United States Department of Agriculture Economic,

(September).

Criado, J. I., Sandoval-Almazan, R., & Gil-Garcia, J. R.

(2013). Government innovation through social media.

Government Information Quarterly, 30(4), 319–326.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.10.003

Crush, J., & Si, Z. (2020). COVID-19 Containment and

Food Security in the Global South. Journal of

Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community

Development, 9(4), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.

2020.094.026

Dadashzadeh, M. (2010). Social Media In Government:

From eGovernment To eGovernance. Journal of

Business & Economics Research (JBER), 8(11), 81–

86. https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v8i11.51

Fahrika, A. I., & Roy, J. (2020). Dampak Pandemi Covid-

19 Terhadap Perkembangan Makro Ekonomi di

Indonesia dan Respon Kebijakan yang Ditempuh.

Inovasi, 16(2), 206–213. Retrieved from http://journal.

feb.unmul.ac.id/index.php/INOVASI/article/view/8255

Fischer, E., & Reuber, A. R. (2011). Social interaction via

new social media: (How) can interactions on Twitter

affect effectual thinking and behavior? Journal of

Business Venturing, 26(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.09.002

Hui Zhang, J. X. (2017). Assimilation of social media in

local Government: an examination of key drivers.

Emeraldinsight. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-09-2016-

0182

Idris, M. (2020). Apa Cukup Beras Bulog Jika Terjadi

Lockdown? Retrieved March 18, 2021, from

Kompas.com website: https://money.kompas.com/

read/2020/03/17/094010326/apa-cukup-beras-bulog-

jika-terjadi-lockdown?page=all

Jones, A. D., Ngure, F. M., Pelto, G., & Young, S. L.

(2013). What are we assessing when we measure food

security? A compendium and review of current

metrics. Advances in Nutrition,

4(5), 481–505.

https://doi.org/10.3945/an.113.004119

Kansiime, M. K., Tambo, J. A., Mugambi, I., Bundi, M.,

Kara, A., & Owuor, C. (2021). COVID-19

implications on household income and food security in

Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment.

How Does the Indonesian Government Communicate Food Security during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis on Indonesia

Official Twitter Account

225

World Development, 137, 105199. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199

Lang, T., & Barling, D. (2012). Food security and food

sustainability: Reformulating the debate.

Geographical Journal, 178(4), 313–326.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2012.00480.x

Latonero, M., & Shklovski, I. (2011). Emergency

Management, Twitter, and Social Media Evangelism.

International Journal of Information Systems for

Crisis Response and Management, 3(4), 1–16.

https://doi.org/10.4018/jiscrm.2011100101

Lee, N. M., & VanDyke, M. S. (2015). Set It and Forget

It: The One-Way Use of Social Media by Government

Agencies Communicating Science. Science

Communication, 37(4), 533–541. https://doi.org/

10.1177/1075547015588600

Malawani, A. D., Nurmandi, A., Purnomo, E. P., &

Rahman, T. (2020). Social media in aid of post

disaster management. Transforming Government:

People, Process and Policy, 14(2), 237–260.

https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-09-2019-0088

Mentang, F. A., Liando, D. M., & Lengkong, J. P. (2017).

Evaluasi Distribusi Program Pemerintah Tentang

Beras Miskin Kepada Masyarakat (Suatu Studi Desa

Totolan Kecamatan Kakas Barat Kabupaten

Minahasa). Jurnal Eksekutif, 1(1).

Moseley, W. G., & Battersby, J. (2020). The Vulnerability

and Resilience of African Food Systems, Food

Security, and Nutrition in the Context of the COVID-

19 Pandemic. African Studies Review, 63(3), 449–461.

https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2020.72

Mursid, F. (2020). Dampak Pandemi, Wapres: Produksi

Beras Diperkirakan Menurun. Retrieved March 18,

2021, from Republika.co.id website: https://republika.

co.id/berita/qfyqd4370/dampak-pandemi-wapres-prod

uksi-beras-diperkirakan-menurun

Murthy, D. (2012). Towards a Sociological Understanding

of Social Media: Theorizing Twitter. Sociology, 46(6),

1059–1073. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511422553

Nurmandi, A., Almarez, D., Roengtam, S., Salahudin,

Jovita, H. D., Kusuma Dewi, D. S., & Efendi, D.

(2018). To what extent is social media used in city

government policy making? Case studies in three

asean cities. Public Policy and Administration, 17(4),

600–618. https://doi.org/10.13165/VPA-18-17-4-08

Prawoto, N., Purnomo, E. P., & Zahra, A. A. (2020). The

impacts of Covid-19 pandemic on socioeconomic

mobility in Indonesia. International Journal of

Economics and Business Administration, 8(3), 57–71.

https://doi.org/10.35808/ijeba/486

Prosekov, A. Y., & Ivanova, S. A. (2018). Food security:

The challenge of the present. Geoforum, 91(August

2017), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.20

18.02.030

Purnomo, E. P., Loilatu, M. J., Nurmandi, A., Salahudin,

Qodir, Z., Sihidi, I. T., & Lutfi, M. (2021). How

Public Transportation Use Social Media Platform

during Covid-19: Study on Jakarta Public

Transportations’ Twitter Accounts? Webology, 18(1),

1–19. https://doi.org/10.14704/WEB/V18I1/WEB18001

Purnomo, E. P., Zahra, A. A., Malawani, A. D., & Anand,

P. (2021). The Kalimantan Forest Fires: An Actor

Analysis Based on Supreme Court Documents in

Indonesia. Sustainability, 13(4), 2342. https://doi.org/

10.3390/su13042342

Ramdani, R., Agustiyara, & Purnomo, E. P. (2021). Big

Data Analysis of COVID-19 Mitigation Policy in

Indonesia: Democratic, Elitist, and Artificial

Intelligence. IOP Conference Series: Earth and

Environmental Science, 717(1), 012023.

https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/717/1/012023

Setiawana, A., Nurmandi, A., Purnomo, E. P., &

Muhammad, A. (2021). Disinformation and

Miscommunication in Government Communication in

Handling COVID-19 Pandemic. Webology, 18(1),

203–218. https://doi.org/10.14704/WEB/V18I1/WEB

18084

Song, C., & Lee, J. (2016). Citizens Use of Social Media

in Government, Perceived Transparency, and Trust in

Government. Public Performance and Management

Review, 39(2), 430–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/153

09576.2015.1108798

The Phan, C., Jain, V., Purnomo, E. P., Islam, M. M.,

Mughal, N., Guerrero, J. W. G., & Ullah, S. (2021).

Controlling environmental pollution: dynamic role of

fiscal decentralization in CO2 emission in Asian

economies. Environmental Science and Pollution

Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15256-9

Udmale, P., Pal, I., Szabo, S., Pramanik, M., & Large, A.

(2020). Global food security in the context of COVID-

19: A scenario-based exploratory analysis. Progress in

Disaster Science, 7, 100120. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.pdisas.2020.100120

Wolfson, J. A., & Leung, C. W. (2020). Food insecurity

and COVID-19: Disparities in early effects for us

adults. Nutrients, 12(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/

10.3390/nu12061648

Zurayk, R. (2020). Pandemic and Food Security: A View

from the Global South. Journal of Agriculture, Food

Systems, and Community Development, 9(3), 1–5.

https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2020.093.014

WEBIST 2021 - 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

226