Can Data Subject Perception of Privacy Risks Be Useful in a Data

Protection Impact Assessment?

Salimeh Dashti

1

, Anderson Santana de Oliveria

2

, Caelin Kaplan

2

, Manuel Dalcastagn

`

e

3

and Silvio Ranise

1,3

1

Fondazione Bruno Kessler, Italy

2

SAP Labs France, France

3

University of Trento, Italy

Keywords:

GDPR, DPIA, Data Protection, Privacy Risks’ Perception.

Abstract:

The General Data Protection Regulation requires, where possible, to seek data subjects perception. Studies

showed that people do not have a correct privacy risk perception. In this paper, we study how lay people

perceive privacy risks once they are made aware and if experts can differentiate between security and privacy

risks.

1 INTRODUCTION

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) re-

quires to conduct a Data Protection Impact Assess-

ment (DPIA) whenever there are high risks to data

subjects’ rights and freedoms. Among other provi-

sions, DPIA asks to seek data subjects’ perception

where appropriate (article 35.9). Several works (Ger-

ber et al., 2019; Shirazi and Volkamer, 2014) pointed

out the low level of awareness of lay people for pri-

vacy risks. In this work, we assess privacy risk per-

ception of lay people when they are given awareness

(RQ1). Identifying risks to data subjects’ rights and

freedoms might not be easy even for experts because

of their multiple overlaps (Brooks et al., 2017). For

this, we investigate whether experts can distinguish

privacy from security risks (RQ2).

To answer RQ1 and RQ2, we have conducted two

surveys based on a scenario to get people into a cer-

tain mindset (Harbach et al., 2014) while avoiding

bias. The results of the surveys show that awareness

helps participants to better estimate privacy impact

when using correct communication; age and context

influence people’s perception; and that experts have

difficulties in setting apart privacy and security risks.

2 MOTIVATION AND

METHODOLOGY

We used surveys to collect people’s attitudes (Wohlin

et al., 2012). Following (Harbach et al., 2014), we in-

troduced a scenario to get people into a certain mind-

set before eliciting their attitudes within that mindset.

Studies (see e.g., (Gerber et al., 2019; Shirazi

and Volkamer, 2014)) showed that lay people are not

aware of privacy risks. Fischoff et al. (Fischhoff

et al., 1978) states that risk perception decreases if

risks are perceived as either voluntary, not imme-

diate, controllable or when using known technolo-

gies. For example, social networks are perceived less

risky as they are known technologies (Gerber et al.,

2019) where people share sensitive information such

as sexual experiences, religion and political opin-

ions (D

´

ıaz Ferreyra et al., 2020), while online banking

or e-commerce services are perceived risky (Skirpan

et al., 2018) due to their immediate impact. We de-

signed a scenario combining the above mentioned as-

pects by presenting participants with a fictitious social

network that provides intimate dating service.

To raise awareness, authors of (Gerber et al., 2019;

D

´

ıaz Ferreyra et al., 2020) warned participants by

bringing the possible privacy risks in the context of

their scenario.

Although, we wanted to examine whether aware-

ness raise concern of lay people, we wanted to avoid

bias by not introducing privacy risks directly related

Dashti, S., Santana de Oliveria, A., Kaplan, C., Dalcastagnè, M. and Ranise, S.

Can Data Subject Perception of Privacy Risks Be Useful in a Data Protection Impact Assessment?.

DOI: 10.5220/0010602608270832

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Secur ity and Cryptography (SECRYPT 2021), pages 827-832

ISBN: 978-989-758-524-1

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

827

to the scenario. People’ risk perception is higher if

they can relate, e.g., losing a job due to data sharing

on Facebook (Garg and Camp, 2013). Thus, we raise

awareness in the opening lines of our surveys by giv-

ing the example of Facebook–Cambridge Analytica

data scandal. This is to challenge people’s perspective

by indicating that known technology are not necessar-

ily less risky.

We designed two online scenario-based surveys,

namely Guided Survey and Unguided Survey.

1

The

former ask participants to estimate the impact of listed

privacy risks, while the latter to identify the privacy

risks related to the scenario. Before running the

Guided Survey, we conducted an internal Pilot Sur-

vey

1

to refine the Guided Survey. We took the pri-

vacy risks listed in Guided and Pilot surveys from

the CNIL Knowledge base (Commission Nationale

de l’Informatique et des Libert

´

es, 2018) document.

The document lists 64 feared events (i.e. “a breach

of personal data security likely to have impacts on

data subjects’ privacy” (Commission Nationale de

l’Informatique et des Libert

´

es, )) and provides exam-

ples of an impact estimation for each. In the follow-

ing, we refer to feared events as privacy risks.

Impact is on a scale of 1 (negligible) to 4 (dra-

matic). The surveys were designed and responded

to in English; and were conducted from mid-October

2019 until the end of February 2020.

Research Questions. Given the aware-

ness warning we raised with the open-

ing line, our first research question is:

RQ1: How do lay people perceive privacy risks?

If experts fail to correctly identify and assess

privacy risks, organizations may fail to comply

with GDPR. Thus our second research question is:

RQ2 : Can information security and data privacy

experts distinguish security risks from privacy risks?

Procedure. The Guided Survey and the Pilot Sur-

vey consist of 9 pages, whereas the Unguided Survey

has 5 pages. The first three pages and the last page

of the surveys are the same. The first page contains

the opening lines, the aim of study, the procedure,

the estimated completion time for the survey and pri-

vacy statement; the second asks participants to spec-

ify their age range, the third provides the scenario,

and the last thanks the participants.

- Pilot Survey. From page four to eight, each page

asks participants to choose a privacy risk from a

given list. The list contains 64 privacy risks. For

each identified privacy risks, they needed to deter-

mine likelihood, impact, and treatment(s). Accord-

ing to the feedback and our observations, we updated

the Guided Survey by reducing the number of privacy

1

https://github.com/stfbk/SECRYPT2021

risks listed to 20 from the 64 in the pilot and eliminat-

ing some descriptions of the privacy risks that turned

out to be confusing for participants.

- Guided Survey. From page four to eight, each page

demonstrates a category of risk. Each category con-

tains four privacy risks (see Table 1). For instance,

the first category is Discrimination and manipula-

tion risk, which contains the following four risks: (1)

Targeted, unique and nonrecurring, lost opportunities

(e.g., refusal of studies, internships or employment,

examination ban); (2) Feeling of violation of funda-

mental rights (e.g. discrimination, freedom of expres-

sion); (3) Targeted online advertising on a private as-

pect that the individual wanted to keep confidential

(e.g., pregnancy advertising, drug treatment); (4) In-

accurate or inappropriate profiling. The survey asked

participants to estimate the level of impact each pri-

vacy risk could have in the case of a data breach.

- Unguided Survey. Page four of the survey contains

five text boxes and asked participants to identify five

privacy risks. For each, they are asked to evaluate

their impact and introduce relevant applicable treat-

ment to address the identified privacy risks.

Recruitment and Participants. For the Pilot Survey,

we reached out to our colleagues at SAP from unre-

lated centers to the field of information technology,

in particular to information security and data privacy.

The survey received 21 responses with all questions

answered. For the Guided Survey, we reached out to

our colleagues, at Fondazione Bruno Kessler (FBK)

from unrelated centers to the field of information

technology. We also involved Bachelor’s and Mas-

ter’s students at University of Trento in the physics

and mathematics department of our university. The

survey received 88 responses with all questions an-

swered. For the Unguided Survey we reached out to

our colleagues who work on information security and

data privacy at FBK and SAP. The Survey had 43 re-

sponses with all questions answered.

Ethics. We follow the best practice for ethical re-

search laid out by both FBK and SAP. The first page

of the surveys informed participants about the pur-

pose and procedure of survey, that they can choose

not to continue the survey at any time during the study

without providing a reason. The identities of the re-

spondents were not collected; we have no means to

link the individual answers to any given respondent.

The participants’ responses are stored privately and

only used for research purposes.

Quantitative Analysis. To draw valid conclusions

we quantitatively analyzed the results of surveys fol-

lowing the methodology described in (Wohlin et al.,

2012). The data we collected from the Guided Survey

were clean as it was a multi-choice form. While the

SECRYPT 2021 - 18th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

828

Unguided Survey had open answers and required to

be cleaned. For this, we applied the Intercoder reli-

ability solution presented in (Kurasaki, 2000), i.e. an

agreement to proxy the validity of the constructs that

emerge from the data in a systematic way (more on

this in Section 3.2).

For the statistical analysis, we verify whether the

null hypothesis (H

0

) can be rejected in favour of the

alternative hypothesis (H

a

). The significant level α is

the highest p-value we accept for rejecting H

0

. A typi-

cal value for α is 0.05; which we have also considered

in our test.

We make no assumption on the distribution of the

data we have collected. Since we wanted to check if

the estimations are above a certain value, we used the

one-sided Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test for a median.

The description on the Quantitative interpretation and

hypothesis test follows (Wohlin et al., 2012).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We synthesize and discuss the results of the surveys,

available at

1

.

3.1 Results of Guided Survey

The Guided Survey answers RQ1. We formulated H

0

as “lay people’s impact estimations are equal or lower

than 2” and H

a

as “lay people’s impact estimations

is greater than 2”. Table 1 shows the results of the

test and the frequency of given impact by participants.

The results show that participants have high concerns

about privacy risks, except for privacy risks “Physi-

cal issues like transient headaches” and “Alteration of

physical integrity, e.g., following an assault, an acci-

dent at home, work, etc.”.

Age is one of the factors that influence people’s

perception of privacy (Youn, 2009). We wanted to

examine this statement. The results show that age

range 18 − 24 are less concerned about the privacy

risk Separation and divorce and Loss of family tie;

while age range 25 − 34 has low concern about the

former and has no concern about physical and Psy-

chological harms. Age range 18 − 24 and 35 − 54

have higher concern about Psychological problem and

Defamation resulting in physical retaliation.

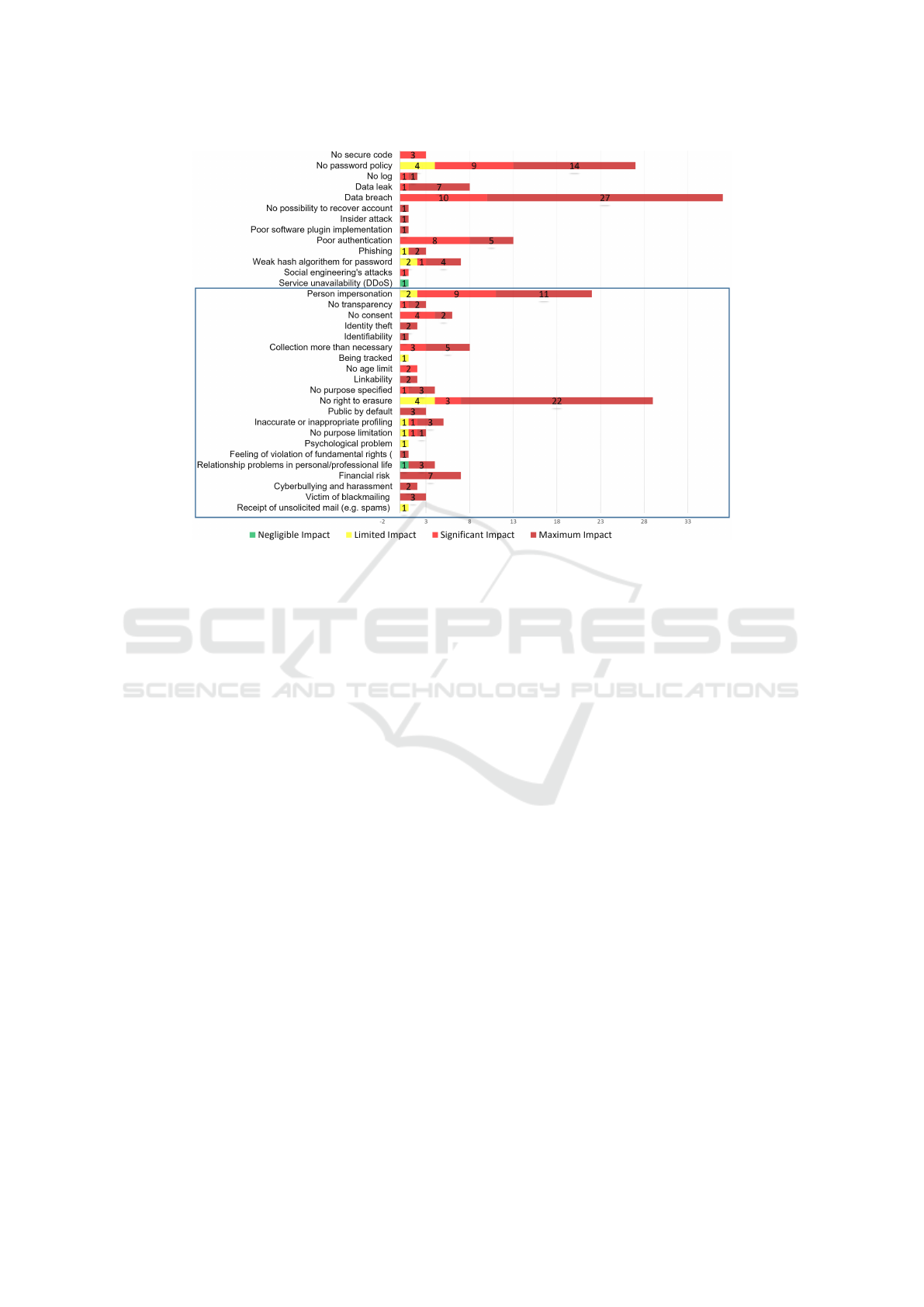

3.2 Results of Unguided Survey

The Unguided Survey answers RQ2. We did not run

the statistical test as the samples were small. The

numbers on the bars indicate the frequency of the

given impact level. The privacy/security text pre-

sented in the Figure are obtained by applying the In-

tercoder reliability solution (Kurasaki, 2000). The

participants have identified 34 issues when 21 of them

are privacy risks, indicated with a rectangle. Partici-

pants were within the age range of 30 to 44.

3.3 RQ 1: People’s Perception

RQ1 aims to assess lay people’ perception of privacy

risks, in the context of a scenario, when given an

awareness warning. As Table 1 shows, except for two

privacy risks related to Physical harm, H

0

is rejected.

We have compared the impact of common pri-

vacy risks in the Guided Survey, listed in Table 3,

with the related risks in the following scenario-based

works (LeBlanc and Biddle, 2012; Harbach et al.,

2014; Gerber et al., 2019; Bellekens et al., 2016;

Mohallick et al., 2018); and three years of the Spe-

cial Eurobarometer general surveys which reach more

than 20,000 people, from 2011 (Special Eurobarom-

eter 359, 2011), 2015 (Special Eurobarometer 431,

2015) and, 2019 (Special Eurobarometer 487a, 2019).

They confirm that people concern about their privacy.

As also stated by Solove in (Solove, 2020), people

care about their privacy, but that does not mean they

are not willing to share their personal data but rather

they evaluate advantages and disadvantages to take

a calculated risk. That contradicts with the works

that state lay people tend to base their decisions on

personal experiences rather than real concerns, such

as (Zhang and Jetter, 2016; Digmayer and Jakobs,

2016; Schneier, 2006; Turner et al., 2011). Where

people seem to be unaware/or not concerned about

privacy could be due to the way they inform them-

selves (Skirpan et al., 2018), or where the risk sce-

nario is abstract (Gerber et al., 2019). Therefore, risk

communication matters to reduce, if not close, the

gap between perception (Skirpan et al., 2018; Turner

et al., 2011) and reality. It could be of help to use

physical and criminal metaphors (Camp, 2009) or

easy-to-recall exampled (e.g., losing a job due to data

sharing on Facebook) (Garg and Camp, 2013)

The result showed that people of different ages

perceive loss of family tie and separation and divorce,

differently (see Table 2); as also stated in some other

works (see e.g., (Smith et al., 2011)), while some oth-

ers (Mohallick et al., 2018; Van Slyke et al., 2006) did

not find any significant difference across age groups.

According to our results, it depends on the category

of the privacy risk under consideration, and cannot be

generalized.

The answer to RQ1 is that raising awareness while

avoiding bias, help lay people to better understand the

Can Data Subject Perception of Privacy Risks Be Useful in a Data Protection Impact Assessment?

829

Table 1: Guided Survey Result.

Impact level Frequency

Category

Privacy Risks

#1

#2

#3

#4

P-value

H0

Ha

Discrimination

/Manipulation

Targeted, unique and nonrecurring, lost opportunities (e.g., refusal of studies,

internships or employment, examination ban)

12

18

37

21

0

Reject

Accept

Feeling of violation of fundamental rights (e.g. discrimination, freedom of

expression)

1

13

40

34

0

Reject

Accept

Targeted online advertising on a private aspect that the individual wanted to

keep confidential (e.g., pregnancy advertising, drug treatment)

4

21

26

37

0

Reject

Accept

Inaccurate or inappropriate profiling

3

24

40

21

0

Reject

Accept

Financial

loss

Non-temporary financial difficulties

12

26

29

21

0

Reject

Accept

Unanticipated payment

7

30

27

24

0

Reject

Accept

Missing career promotion

13

26

30

19

0

Reject

Accept

Financial loss as a result of a fraud (e.g., after an attempted phishing)

5

18

28

37

0

Reject

Accept

Social

Disadvantage

Loss of family tie

20

23

21

24

0

Reject

Accept

Separation or divorce

29

18

21

20

0.0044

Reject

Accept

Receipt of targeted mailings likely to damage reputation

9

23

33

23

0

Reject

Accept

Cyberbullying and harassment like blackmailing

10

11

27

40

0

Reject

Accept

Deprived to

exercise right

Losing control over your data

0

13

37

38

0

Reject

Accept

Reuse of data published on websites for the purpose of targeted advertising

(information to social networks, reuse for paper mailing)

2

7

30

49

0

Reject

Accept

Feeling of invasion of privacy

6

5

31

46

0

Reject

Accept

Blocked online services account (e.g., games, administration)

12

27

34

15

0

Reject

Accept

Physical harm

Psychological problem (e.g., development of a phobia, loss of self-esteem)

19

24

19

26

0

Reject

Accept

Defamation resulting in physical retaliation

21

21

31

15

0.0001

Reject

Accept

Physical issues like transient headaches

29

34

17

8

0.5131

Accept

Reject

Alteration of physical integrity, e.g., following an assault, an accident at home,

work, etc.

24

35

18

11

0.1055

Accept

Reject

LEGEND. #1: Frequency of Negligible, #2: Frequency of Limited, #3: Frequency of Significant, #4: Frequency of Maximum

Privacy Concerns

P-Value

age 18 to 25

P-Value

25 to 34

P-Value

35 to 54

Loss of family tie

0.2735

Accept

0.004

Reject

0.0002

Reject

Separation or divorce

0.7747

Accept

0.0906

Accept

0.0003

Reject

Psychological problem

0.0008

Reject

0.2029

Accept

0.0015

Reject

Defamation resulting in physical retaliation

0.0388

Reject

0.1509

Accept

0.0006

Reject

Physical issues like transient headaches

0.4216

Accept

0.4153

Accept

0.7561

Accept

Alteration of physical integrity, e.g., following an assault, an accident at home, work

0.1006

Accept

0.384

Accept

0.305

Accept

Table 2: Age Range Impact Analysis for Privacy Risks that Accept the H

0

.

Impact level Frequency

Category

Privacy Risks

#1

#2

#3

#4

P-value

H0<=2

Ha>2

Discrimination

/Manipulation

Targeted, unique and nonrecurring, lost opportunities (e.g., refusal of studies,

internships or employment, examination ban)

12

18

37

21

0

Reject

Accept

Feeling of violation of fundamental rights

1

13

40

34

0

Reject

Accept

Targeted online advertising on a private aspect that the individual wanted to

keep confidential (e.g., pregnancy advertising, drug treatment)

4

21

26

37

0

Reject

Accept

Inaccurate or inappropriate profiling

3

24

40

21

0

Reject

Accept

Financial

loss

Non-temporary financial difficulties

12

26

29

26

0

Reject

Accept

Unanticipated payment

7

30

27

24

0

Reject

Accept

Missing career promotion

13

26

30

19

0

Reject

Accept

Financial loss as a result of a fraud (e.g., after an attempted phishing)

5

18

28

37

0

Reject

Accept

Social

Disadvantage

Loss of family tie

20

23

21

24

0

Reject

Accept

Separation or divorce

29

18

21

20

0.0044

Reject

Accept

Receipt of targeted mailings likely to damage reputation

9

23

33

23

0

Reject

Accept

Cyberbullying and harassment like blackmailing

10

11

27

40

0

Reject

Accept

Deprived to

exercise right

Losing control over your data

0

13

37

38

0

Reject

Accept

Reuse of data published on websites for the purpose of targeted advertising

(information to social networks, reuse for paper mailing)

2

7

30

49

0

Reject

Accept

Feeling of invasion of privacy

6

5

31

46

0

Reject

Accept

Blocked online services account (e.g., games, administration)

12

27

34

15

0

Reject

Accept

Physical harm

Psychological problem

19

24

19

26

0

Reject

Accept

Defamation resulting in physical retaliation

21

21

31

15

0.0001

Reject

Accept

Physical issues like transient headaches

29

34

17

8

0.5131

Accept

Reject

Alteration of physical integrity, e.g., following an assault, an accident at home,

work.

24

35

18

11

0.1055

Accept

Reject

LEGEND. #1: Frequency of Negligible, #2: Frequency of Limited, #3: Frequency of Significant, #4: Frequency of Maximum

Privacy Concerns

P-Value

age 18 to 25

P-Value

25 to 34

P-Value

35 to 54

Loss of family tie

0.2735

Accept

0.004

Reject

0.0002

Reject

Separation or divorce

0.7747

Accept

0.0906

Accept

0.0003

Reject

Psychological problem

0.0008

Reject

0.2029

Accept

0.0015

Reject

Defamation resulting in physical retaliation

0.0388

Reject

0.1509

Accept

0.0006

Reject

Physical issues like transient headaches

0.4216

Accept

0.4153

Accept

0.7561

Accept

Alteration of physical integrity, e.g., following an assault, an accident at home, work

0.1006

Accept

0.384

Accept

0.305

Accept

Table 3: Impact Estimations of Same Privacy Risks By Different Works.

Privacy Risks

Guided Survey

Other Works

Losing control over one’s data

Maximum (35.23%)

Significant (40.91%)

[EU2011]: 78% (out of 26,574) feel to have no or partial control.

[EU2015]: 67% (out of 16,244) concerned to have no control.

[EU2019]: 78% (out of 15,915) concerned to have no control.

Reuse of data published on websites for the purpose of

targeted advertising (information to social networks, reuse

for paper mailing)

Maximum (44.32%)

Significant (34.9%)

EU2011: 70\% (out of 26,574) secondary purposes concern.

EU2015: 69\% (out of 27,980) secondary purposes concern.

[Mohallick et al., 2018]: secondary purpose is the main concern.

Targeted online advertising on a private aspect that the

individual wanted to keep confidential

(e.g., pregnancy advertising, drug treatment)

Maximum (40.90%)

Significant (30.68%)

EU2011: 54% (out of 26,574) significant to maximum concern.

EU2019: 53% (out of 21,707) significant to maximum concern.

[Bellekens ´ et al., 2016]: categorized them as the most impactful.

Inaccurate or inappropriate profiling

Maximum (25%)

Significant (44.32%)

Financial loss as a result of a fraud (e.g., after an attempted

phishing)

Maximum (40.91%)

Significant (31.82%)

[Gerber et al., 2019; Bellekens et al., 2016, Harbach et al., 2014,

LeBlanc and Biddle, 2012]: financial is impactful.

LEGEND. EU2011: [Special Eurobarometer 359, 2011], EU2015: [ Special Eurobarometer 431, 2015], EU2019: [ Special Eurobarometer 487a. 2019]

impact of privacy risks when unambiguous language

and concrete examples are used. As context influence

peoples’ perceptions, controllers should not use the

result of an existing data processing without consid-

ering the context.

3.4 RQ2: Expert and Privacy Risks

The second research question aims to understand

whether experts can distinguish privacy risks from

security risks. Figure 1 shows that the participants

have identified 34 issues among which 21 are pri-

vacy risks. Given that the participants are explicitly

SECRYPT 2021 - 18th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

830

Figure 1: The Identified Privacy risks With the Frequency of Given Impacts.

asked to identify privacy risks, the answer to RQ2 is

that experts have difficulties in setting apart privacy

and security risks. Failing to recognize the bound-

aries between security and privacy can result in mis-

judging either the necessity of the DPIA or the impact

level of data processing on data subjects. Controllers

may want to collaborate with legal fellows and Data

Protection Officers. It is also good practice to use

tools that can assist to identify privacy risks (see, e.g.,

(Dashti and Ranise, 2019)).

4 RELATED WORK

The DPIA under the GDPR is a tool for managing

risks to the rights of the data subjects, and thus takes

their perspective(EDPB, ).

Different surveys examined people’s perception.

(Gerber et al., 2019) considered both abstract and spe-

cific scenarios in three different use cases. Specific

scenarios describe how collected data can be abused.

Accordingly, we raise awareness about possible pri-

vacy risks. To avoid bias, we did not put the risks

in the context of the scenario but in the opening lines

of the surveys. (Oomen and Leenes, 2008) inves-

tigates the relation between privacy risk perception

and the privacy actions people take, and conclude that

they are most concerned about invasion in their pri-

vate sphere than dignity and an unjust treatment as

a result of abuse/misuse of their personal data. This

could be because,, unlike our survey, they do not raise.

Experts and lay people perceive privacy concerns

differently. The former judge based on their past

experiences (Zhang and Jetter, 2016; Digmayer and

Jakobs, 2016), with no awareness on specific privacy

concerns (Shirazi and Volkamer, 2014). The latter

see privacy issues as either an abstract problem with

no immediate or not a problem at all (Lahlou et al.,

2005). The work (Tahaei et al., 2021) suggests that

the ”I’ve got Nothing to Hide” mentality makes it

challenging to advocate for privacy values. The re-

sults of our Unguided Survey also suggest that infor-

mation experts experience difficulties in setting apart

privacy and security risks.

5 CONCLUSION

The Guided Survey investigated people’s perception

of privacy concerns when giving them an aware-

ness warning beforehand. We observed that al-

though awareness helps people to better perceive pri-

vacy risks, the language used to communicate risks

matters–less vague and more familiar risk examples

are better; and context impacts on privacy risks’ per-

ception, highlighting the fact that controllers should

not take the impact estimation from previous data pro-

tection impact assessments as they are, without con-

sidering the context. The Unguided Survey suggests

that even experts may have a hard time to set apart pri-

Can Data Subject Perception of Privacy Risks Be Useful in a Data Protection Impact Assessment?

831

vacy and security risks. The results showed that they

confuse them, which may lead to non-compliance.

REFERENCES

Bellekens, X., Hamilton, A., Seeam, P., Nieradzinska,

K., Franssen, Q., and Seeam, A. (2016). Pervasive

eHealth services a security and privacy risk awareness

survey. In CyberSA. IEEE.

Brooks, S., Brooks, S., Garcia, M., Lefkovitz, N., Light-

man, S., and Nadeau, E. (2017). An introduction to

privacy engineering and risk management in federal

systems. NIST.

Camp, L. J. (2009). Mental models of privacy and security.

IEEE Technology and society magazine.

Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libert

´

es.

How to carry out a PIA.

Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libert

´

es

(2018). Privacy Impact Assessment: Knowledge

Base.

Dashti, S. and Ranise, S. (2019). Tool-assisted risk analysis

for data protection impact assessment. In IFIP SEC.

Springer.

D

´

ıaz Ferreyra, N. E., Kroll, T., A

¨

ımeur, E., Stieglitz, S.,

and Heisel, M. (2020). Preventative nudges: Intro-

ducing risk cues for supporting online self-disclosure

decisions. Information, 11.

Digmayer, C. and Jakobs, E.-M. (2016). Risk perception

of complex technology innovations: Perspectives of

experts and laymen. In ProComm. IEEE.

EDPB. Guidelines on data protection impact assessment

and determining whether processing is “likely to re-

sult in a high risk” for the purposes of regulation

2016/679.

Fischhoff, B., Slovic, P., Lichtenstein, S., Read, S., and

Combs, B. (1978). How safe is safe enough? a

psychometric study of attitudes towards technological

risks and benefits. Policy sciences.

Garg, V. and Camp, J. (2013). Heuristics and biases: im-

plications for security design. IEEE Technology and

Society Magazine.

Gerber, N., Reinheimer, B., and Volkamer, M. (2019). In-

vestigating people’s privacy risk perception. Proceed-

ings on PET, 2019.

Harbach, M., Fahl, S., and Smith, M. (2014). Who’s afraid

of which bad wolf? a survey of it security risk aware-

ness. In IEEE 27th CSF.

Kurasaki, K. S. (2000). Intercoder reliability for validating

conclusions drawn from open-ended interview data.

Field methods.

Lahlou, S., Langheinrich, M., and R

¨

ocker, C. (2005). Pri-

vacy and trust issues with invisible computers. CACM.

LeBlanc, D. and Biddle, R. (2012). Risk perception of

internet-related activities. In PST. IEEE.

Mohallick, I., De Moor, K.,

¨

Ozg

¨

obek,

¨

O., and Gulla, J. A.

(2018). Towards new privacy regulations in Europe:

Users’ privacy perception in recommender systems. In

SpaCCS. Springer.

Oomen, I. and Leenes, R. (2008). Privacy risk perceptions

and privacy protection strategies. In Policies and re-

search in identity management. Springer.

Schneier, B. (2006). Beyond fear: Thinking sensibly about

security in an uncertain world. Springer Science &

Business Media.

Shirazi, F. and Volkamer, M. (2014). What deters jane from

preventing identification and tracking on the web? In

Proceedings of the WPES.

Skirpan, M. W., Yeh, T., and Fiesler, C. (2018). What’s

at stake: Characterizing risk perceptions of emerging

technologies. In Proceedings of CHI.

Smith, H. J., Dinev, T., and Xu, H. (2011). Information pri-

vacy research: an interdisciplinary review. MIS quar-

terly.

Solove, D. J. (2020). The myth of the privacy paradox.

Available at SSRN.

Special Eurobarometer 359 (2011). Attitudes on data pro-

tection and electronic identity in the EU.

Special Eurobarometer 431 (2015). Data protection.

Special Eurobarometer 487a (2019). 87a. general data pro-

tection regulation.

Tahaei, M., Frik, A., and Vaniea, K. (2021). Privacy cham-

pions in software teams: Understanding their motiva-

tions, strategies, and challenges.

Turner, M. M., Skubisz, C., and Rimal, R. N. (2011). The-

ory and practice in risk communication: A review of

the literature and visions for the future. In The Rout-

ledge handbook of health communication. Routledge.

Van Slyke, C., Shim, J., Johnson, R., and Jiang, J. J. (2006).

Concern for information privacy and online consumer

purchasing. JAIS, 7.

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., H

¨

ost, M., Ohlsson, M. C., Reg-

nell, B., and Wessl

´

en, A. (2012). Experimentation in

software engineering. Springer Science & Business

Media.

Youn, S. (2009). Determinants of online privacy con-

cern and its influence on privacy protection behaviors

among young adolescents. JCA, 43.

Zhang, P. and Jetter, A. (2016). Understanding risk percep-

tion using fuzzy cognitive maps. In PICMET. IEEE.

SECRYPT 2021 - 18th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

832