Do Employees Stay Satisfied in Times of Digital Change? On How

Motivation Aware Systems Might Mitigate Motivational Deficits

Frederike Marie Oschinsky

a

and Bjoern Niehaves

b

Chair of Information Systems Research, University of Siegen, Kohlbettstrasse 15, 57072 Siegen, Germany

Keywords: Employee Motivation, Performance, Satisfaction, Attention Aware Systems, Motivation Aware Systems.

Abstract: Fostering motivation seems a crucial parameter at the time of the global pandemic and far beyond. It helps

master the challenge that employees spend up to half of their working time in an unproductive manner –

especially when using technology. Against this background, Information Systems (IS) research started to

design systems capable of supporting employees in enhancing their productivity and focus at work: attention

aware systems. We follow up on the regarding design implications in current literature and similarly propose

the development of motivation aware system to enhance employee motivation. We suggest to follow a mixed-

method approach to study whether the development of these systems could be seen as a promising avenue.

Also, we outline how to design such systems and point at possibilities for future research.

1 INTRODUCTION

Employees spend up to half of their working time in

an unproductive manner – oftentimes using

information technologies (IT) (Bennett & Naumann,

2005). Studies show that, since an increasing number

of them works remotely, employees are diminishingly

controlled by their colleagues and executives, and

prevalently use their privately owned devices for

professional purposes (Klesel et al., 2017). The Bring

Your Own Device (BYOD) movement already led to

the implementation of various organizational

guidelines intended to regulate how employees use

their private equipment. Nowadays, the ongoing

global pandemic resulted in an even more urgent

demand for strategies on how to use privately-owned

devices when working outside the office. Because the

companies’ IT departments have only limited control

over applications and downloads these days, it seems

strikingly important to find ways to ensure the

employees’ productivity when using private IT.

Fostering motivation seems a crucial parameter to

master this challenge. At the individual level, being

motivated increases performance, well-being and

creativity, while it minimizes misconduct and

absenteeism (e.g., Baard et al., 2004; Zhang & Bartol,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2591-9860

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2682-6009

2010). At the organizational level, a high level of

motivation increases overall productivity and

profitability, growth and competitiveness as well as

customer satisfaction and retention (e.g., Noe et al.,

2017). Thus, the interest in motivation principles is

well-established and yet steadily increasing.

Doing research about motivational obstacles and

drivers is fruitful, since it is imperative for

organizations to create a motivating working

environment so that employees remain willing to

exploit their full potential and productivity. Against

this background, Information Systems (IS) research

already set focus and started to design systems

capable of supporting employees in doing so:

attention aware systems. These systems are able to

detect a user’s current attentional state, evaluate

alternative attentional states and employ focus switch

or maintenance (Roda & Thomas, 2006).

Consequently, we see great potential for the

development of specific systems capable of

supporting motivational mechanisms: motivation

aware systems. Technologies, in addition to allowing

fast access to information and people, should be

designed to mitigate against motivational deficits.

Based on current literature and latest empirical

evidence, we derive three research questions (RQs):

Oschinsky, F. and Niehaves, B.

Do Employees Stay Satisfied in Times of Digital Change? On How Motivation Aware Systems Might Mitigate Motivational Deficits.

DOI: 10.5220/0010621601770182

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B 2021), pages 177-182

ISBN: 978-989-758-527-2

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

177

RQ1: Which factors influence the motivation of

employees in the working environment?

RQ2: Can the development of motivation aware

systems be seen as a promising avenue to enhance

employee motivation?

RQ3: How can a motivation aware system be

designed?

To answer these questions, we seek to compile the

current state of research and to shed light on the most

important influences on employee motivation. With

this research-in-progress paper, we will describe the

theoretical foundation of such a system. Our work

thereby merges existing knowledge of the fields of

business administration, management, psychology

and IS research (Chapter 2) to derive implications for

design (Chapter 3). After concluding remarks about

the benefit and limitation of our approach, possible

ways of future research are shown (Chapter 4).

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Motivation is defined as the direction, intensity, and

persistence of a will to execute a behavior towards or

away from goals (Kanfer et al., 2008). Motivation is

thus not an actual behavior, but the willingness to

undertake it. It is substantial among the various

antecedents of human behavior, which can be divided

into four groups: Besides motivation, behavior is

mostly affected by individual abilities, an enabling

context and the social environment (Rosenstiel, 2007,

p. 57). There are interactions between the antecedents

of human behavior as they all depend on individual

experience and subjective perception. However, we

will focus only on motivation.

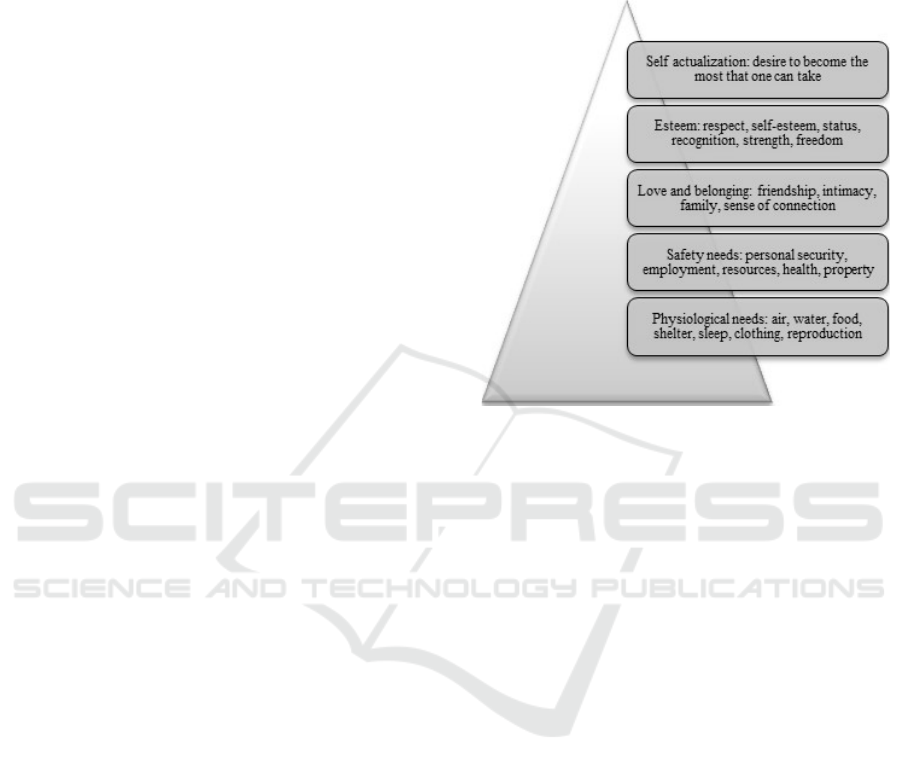

2.1 Maslow’s Pyramid

Maslow’s Need Pyramid (1954) is as an early

example of motivation theories. Instead of motif he

uses the term need, because scientists in those years

frequently talked about needs, drivers, and even

instincts interchangeably. The author assumes that

underlying needs drive behavior and states a

hierarchical structure: At the lowest level, there are

basic physiological needs (such as hunger). If these

are satisfied, security needs (such as stability) are

activated at the next level. They are followed by

social needs (such as belonging) and needs for self-

realization (i.e., self-esteem via respect and self-

actualization via the pursue of inner talent) at the top.

The assumption of levels and hierarchy implies that

only when a lower need is satisfied, the upper one is

activated. By properly identifying needs, Maslow

presumes, people can be effectively motivated.

Figure 1: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow’s assumptions have successfully spread

in theory and practice as a kind of motivation

checklist. For instance, they explain why it is not

purposeful to allow an employee to choose where to

work (i.e., self-realization), if the social need for

contact is not satisfied. However, empirical data rises

doubt: Observations show people who trade their

security for status or who risk their health for self-

fulfillment. In addition, the importance of the needs

can vary greatly depending on age and the stage of

life (Gebert & von Rosenstiel, 2002). Maslow’s

theory lacks essential motifs such as power and does

not include differences in culture (e.g., Stajkovic &

Luthans, 1998; Winter, 2001; Steel, 2007). It does not

show what motivational leadership or a motivational

work environment should look like, how to design

tasks or how to formulate organizational goals. Thus,

we aim at finding a more promising approach.

2.2 Lewin’s External Influences and

Internal Influences on Motivation

Lewin considers external and internal influences on

human motivation more systematically (1936). He

describes behavior as a function of person and

environment. External influences on employees’

motivation are the design of a task (e.g., Bakker &

Demerouti, 2007) or a company’s incentive system

(e.g., Stajkovic & Luthans, 2003). Other important

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

178

factors are team work, leadership and the

organization itself in that it shapes the above aspects

with its corporate culture. Internal influences on

employees’ motivation are the personality of the

individual (e.g., Judge et al., 2007) and their ability to

regenerate from work and stress (e.g., Sonnentag,

2003; Sonnentag et al., 2010). Other essential factors

are self-efficacy, individual habits, optimism and

self-regulation. Employee motivation arises from the

interplay of environmental influences and

characteristics and the traits and states of individuals.

2.3 Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory of

Motivation

To find out whether the development of motivation

aware systems can be seen as a promising avenue to

enhance employee motivation, we take into account

the vast psychological literature. For instance,

Herzberg and his colleagues were interested in the

external influences of why someone is motivated at

work (1959). They moved away from studying

general motives towards concrete aspects in the

environment of employees. In their studies, they

asked numerous employees from different branches

and hierarchical levels about typical situations at

work. Based on frequency lists, the researchers

discovered an interesting pattern: They distinguished

two factors a) dissatisfying ‘hygiene factors’, and b)

satisfying ‘motivators’ (Herzberg, 1972). Against this

background, they deduced that dissatisfaction and

satisfaction represent two different dimensions, and

not simply opposite poles of a single dimension.

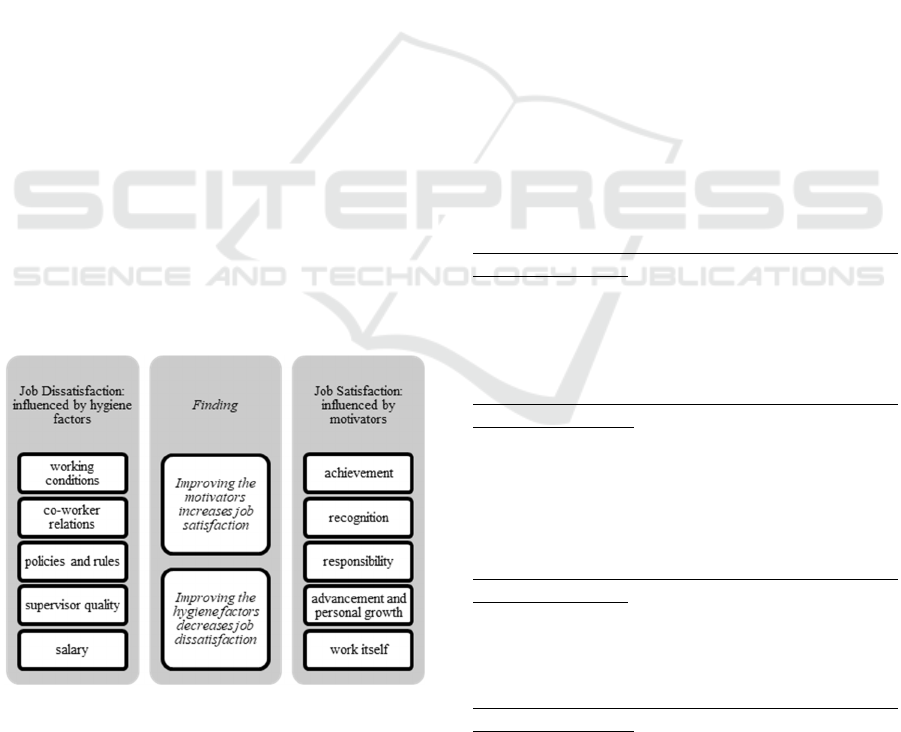

Figure 2: Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory of Motivation.

The dimension of hygiene factors describes the

work environment (e.g., the quality of relationships).

Exemplary hygiene factors are leadership, working

conditions, administration or payment. If the hygiene

factors are favorable, there is no dissatisfaction – but

they do not determine whether employees are

motivated or not. The dimension of motivators

focuses on the work itself (e.g., performance

experience). Exemplary motivators are responsibility,

recognition, the content of the task and perception of

growth. This dimension determines whether there is

dissatisfaction as it produces motivation – but only if

hygiene factors have been optimized. According to

Herzberg (1972), the opposite of dissatisfaction is

thus not contentment but only the absence of

dissatisfaction.

When we compare Maslow’s Hierarchy of Need

with Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory, we see that they

overlap at some points. The basic psychological

needs for safety and security as well as for belonging

and love fit well with hygiene factors. Interpersonal

relations, supervision, company policies and

administration, salary, and working conditions are

addressed. The needs on a higher hierarchy (i.e.,

esteem and self-actualization) are accompanied by

Herzberg’s motivators. They illustrate achievement,

recognition, responsibility, advancement and work as

a value for itself. Bearing this insight in mind, four

states can be discriminated from each other.

Transitions are fluent, but the states pinpoint the

central idea that in the case of dissatisfaction,

motivation goes nowhere.

The condition of the hygiene factors is bad;

motivators are low.

The employees are dissatisfied and there is

nothing that could motivate them in the short term.

This likely results in high turnover, low attendance

and low performance.

The condition of the hygiene factors is bad;

motivators are high.

Although the employees like their job, a bad

working environment suffocates the joy of work.

Inefficient administration and bureaucracy, a bad

relationship with the leader or team constantly

demotivate.

The condition of the hygiene factors is good;

motivators are low.

The employees are in a great environment, with a

great boss, nice colleagues and well-organized

processes. Unfortunately, the task offers no fun at all.

The condition of the hygiene factors is good;

motivators are high.

The employees find themselves in an optimal

environment, are satisfied and have a dreamlike job,

which really motivates. This stage is where

sustainable motivation comes about.

Do Employees Stay Satisfied in Times of Digital Change? On How Motivation Aware Systems Might Mitigate Motivational Deficits

179

The empirical investigation in a concrete context

for a specific target group (i.e., employees) provides

meaningful categories. This is why the two-factor

theory has also been applied in IS research. For

instance, Cenfetelli (2004) found out that the

rejection to use IT is best predicted by inhibitors (i.e.,

hygiene factors) that discourage usage when present,

but do not necessarily favor usage when absent (see

also Bhattacherjee & Hikmet, 2007; Hsieh et al.,

2014). Next, the results are much more manageable

and useful for practical purposes than, amongst

others, Maslow’s Pyramid. With Herzberg’s change

of perspective, companies and executives were given

more concrete advice to promote employee

motivation. Moreover, looking at the four states, we

see that the lower the motivators, the higher the

potential of applying motivation aware systems.

3 TOWARDS DESIGNING

MOTIVATION AWARE

SYSTEMS

Understanding how our brain works gives us

important clues about how to increase employee

motivation. For designing motivation aware system,

we again dive into psychological literature as it

reveals that human affect optimization is associated

with the release of substances in the brain (e.g.,

endorphins for positive feelings and cortisol for

negative feelings) and that specific physical reactions

are linked to their release (e.g., an increase in

heartbeat) (see also Kuhl, 2001). Events in the

environment or in one’s own body are registered by

the limbic system, which in turn activates behavior-

controlling centers. Thus, the measurement of

specific brain substances, limbic system activity and

physical reaction make it possible to draw

conclusions on a person’s state of affect quite reliably

(Roth, 2017). This insight is very valuable when it

comes to designing a motivation aware system.

Again, we are aware that research stemming from

neuroscience, psychology, and medicine already

address bodily responses of humans, whose insights

open a promising avenue for future studies. On top of

that, in our own follow-up studies, we will put this

work in the perspective of the design science process,

so that our next steps become prominent. In addition,

this will help understand our work’s relation to the

current body of knowledge and empirical evidence.

One important clue is that rewards at work must

have some degree of uncertainty. They must be an

exception, which can be implemented as a feature in

a motivation aware system. Another important clue is

that habits carry reward in themselves. It is fun to do

things quickly, accurately and effectively. The more

tasks are practiced and established, the less emotional

effort is required to carry out an activity. To hold on

to the proven conveys the feeling of security and

competence and reduces fear and skepticism.

Motivation aware systems can detect the necessity to

do automated things at work. This can greatly

increase to feel comfortable work and thus, enhance

employee motivation.

To answer our RQs, we suggest to follow a mixed-

method approach: To elaborate on RQ1 and RQ2, we

will send a survey to 350 small, medium-sized and

large companies in (left out for review). If the results

are promising, a second survey is planned abroad,

taking into account cultural features. To elaborate on

RQ3, we will do both a systematic literature review

and expert interviews to get an idea of how the

insights about attention aware systems can stimulate

the design of motivation aware systems (e.g., Which

measurement methods could be used to measure

motivation?). In the end, we plan to do focus group

interviews to discuss the preliminary findings and to

draw conclusion on how to refine our study. Data

analysis will be in line with data collection either in

the form of quantitative (i.e., structural equation

modeling) or qualitative analysis (i.e., content

analysis). The results will be interpreted and

discussed in an interdisciplinary team.

4 DISCUSSION

At this point, we do not at all claim completeness or

generalizability as we have only deduced our

approach theoretically. Against this background, we

want to address a few critical factors of our work so

far and present ways for future research: First,

literature shows that job satisfaction can be partly

innate and not externally determined (Hahn et al.,

2016). Moreover, the widely assumed positive linear

relationship between job satisfaction and motivation

seems not to exist (Bowling, 2007). For instance, job

satisfaction can rise from achieving own goals

without meeting organizational goals. Future research

can offer a more differentiated perspective and take

into account important confounding factors such as

openness to career moves (e.g., working one’s way up

with job shopping). Moreover, it will be interesting to

study whether motivational deficits really persuade

employees to change jobs.

Being a research-in-progress paper, our work still

lacks clarity and empirical insight. Against this

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

180

background, future research is invited to come up

with narrower research question to approach the

broad research question mentioned in this manuscript.

On top of that, they can acknowledge that working

environments may differ greatly between different

jobs and domains. The ongoing debate of establishing

‘new work’ in a post-pandemic world highlights the

need for more focus and unerring conceptualization.

Furthermore, future studies can consider

additional system design options when it comes to the

question of how motivation aware systems can

increase employee motivation. For example, the

differentiation into hedonic and utilitarian systems

could have explanatory power (van der Heijden,

2004). On top of that, future work can address the

very close relationship between motivation and self-

efficacy (Bandura & Wessels, 1997). Self-efficient

employees tenaciously pursue their goals

(persistence) and estimate what effort is worthwhile

for which task (reality orientation). They feel quite

satisfied and capable and make the important

experience that the pursuit of self-determined goals is

a reward in itself. In this respect, looking at the

correlation of employee motivation and self-efficacy

opens the door for interesting insights.

In addition, applying Herzberg’s Two-Factor

Theory of Motivation offers several pitfalls. First, the

four states are still abstract. The author focused on

essential aspects in the environment of employees,

but still did not show what motivating leadership or

motivating work tasks exactly look like. In addition,

the distinct assignment as a hygiene factor or

motivator is narrow. Among others, leadership is

categorized as a hygiene factors, but has been shown

to be a powerful motivator that can do much more

than simply not demotivating employees (e.g., Aryee

et al., 2012; Avolio, 2011; Bass & Riggio, 2006). On

top of that, the generalization and validity of

motivators and hygiene factors are vague. Depending

on the situation, the meanings change. For example,

salary can become more significant during an

economic crisis. The meanings vary between subjects

(e.g., Minton et al., 1980). Next, the motivators

themselves are somehow delusive, since people are

more likely to seek the reasons for success in

themselves, but attribute the reasons for failure to

external factors to protect their self-esteem (e.g.,

Mezulis et al., 2004). Finally, we are aware that the

mentioned theories are still basic and that researchers

have built on them for many years. In particular, the

technology adoption literature published technology-

related findings such as the Motivational Technology

Acceptance Model by Davis’s lab.

However, in a constantly changing working

environment, we see great potential in researching

factors that are related to employee motivation, using

the application of motivation aware systems as a

contemporary example. Future research can show

how to design such systems in more detail, study

whether they really motivate to achieve higher

performance and provide a deeper analysis of relevant

related approaches. Based on these future insights,

conclusions can be drawn on how employees can stay

motivated during the global pandemic and in times of

continuous change and digital transformation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Volkswagen

Foundation (grant: 96982).

REFERENCES

Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Zhou, Q., & Hartnell, C. A.

(2012). Transformational leadership, innovative

behavior, and task performance: Test of mediation and

moderation processes. Human Performance, 25(1), 1–

25.

Avolio, B. J. (2011). Full range leadership development

(2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic

Need Satisfaction: A Motivational Basis of

Performance and Weil-Being in Two Work Settings.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–

2068.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands‐

Resources model: State of the art. Journal of

Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328.

Bandura, A., & Wessels, S. (1997). Self-efficacy. W.H.

Freeman & Company.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational

leadership (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

Bennett, N., & Naumann, S. E. (2005). Withholding Effort

at Work: Understanding and Preventing Shirking, Job

Neglect, Social Loafing, and Free Riding. In Managing

Organizational Deviance (pp. 113–130). SAGE

Publications.

Bhattacherjee, A., & Hikmet, N. (2007). Physicians’

resistance toward healthcare information technology: A

theoretical model and empirical test. European Journal

of Information Systems, 16(6), 725–737.

Bowling, N. A. (2007). Is the job satisfaction–job

performance relationship spurious? A meta-analytic

examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(2),

167–185.

Cenfetelli, R. (2004). Inhibitors and Enablers as Dual

Factor Concepts in Technology Usage. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 5(11), 472–492.

Do Employees Stay Satisfied in Times of Digital Change? On How Motivation Aware Systems Might Mitigate Motivational Deficits

181

Gebert, D., & von Rosenstiel, L. (2002).

Organisationspsychologie: Person und Organisation

(5th ed.). Kohlhammer.

Hahn, E., Gottschling, J., König, C. J., & Spinath, F. M.

(2016). The heritability of job satisfaction reconsidered:

Only unique environmental influences beyond

personality. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31(2),

217–231.

Herzberg, F. (1972). One more time: How do you motivate

employees. In Harvard Business Review (pp. 113–125).

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snijderman, B. B. (1959). The

Motivation to Work. Wiley.

Hsieh, P.-J., Lai, H.-M., & Ye, Y.-S. (2014). Patients’

Acceptance and Reistance toward the Health Cloud: An

Integration of Technology Acceptance and Status Quo

Bias Perspectives. PACIS 2014 Proceedings, 230, 15.

Judge, T. A., Jackson, C., Shaw, J. C., Scott, B. A., & Rich,

B. L. (2007). Is the effect of self-efficacy on job/task

performance an epiphenomenon. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 92, 107–127.

Kanfer, R., Chen, G., & Pritchard, R. D. (2008). Work

Motivation Past, Present, And Future. Routledge.

Klesel, M., Lemmer, K., & Bretschneider, U. (2017).

Transgressive Use of Technology. Proceedings of the

Thirty Eighth International Conference on Information

Systems (ICIS).

Kuhl, J. (2001). Motivation und persönlichkeit:

Interaktionen psychischer systeme. Hogrefe.

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology.

McGraw-Hill.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Personality and Motivation. Harper

and Row.

Mezulis, A. H., Abramson, L. Y., Hyde, J. S., & Hankin, B.

L. (2004). Is there a universal positivity bias in

attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual,

developmental, and cultural differences in the self-

serving attributional bias. Psychological Bulletin,

130(5), 711.

Minton, H. L., Schneider, F. W., & Wrightsman, L. S.

(1980). Differential Psychology. Cole Publishing

Company.

Noe, R. A., Hollenbeck, J. R., Gerhart, B., & Wright, P. M.

(2017). Human resource management: Gaining a

competitive advantage. McGraw-Hill Education.

Roda, C., & Thomas, J. (2006). Attention Aware systems:

Theories, Applications, and Research Agenda.

Computers in Human Behavior, 22(4), 557–587.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.12.005

Rosenstiel, L. von. (2007). Grundlagen der

Organisationspsychologie: Basiswissen und

Anwendungshinweise (6th ed.). Schäffer-Poeschel.

Roth, G. (2017). Persönlichkeit, Entscheidung und

Verhalten: Warum es so schwierig ist, sich und andere

zu ändern - Aktualisierte und erweiterte Auflage (12.

Druckaufl.). Klett-Cotta.

Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and

proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between

nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology,

88(3), 518.

Sonnentag, S., Binnewies, C., & Mojza, E. J. (2010).

Staying well and engaged when demands are high: The

role of psychological detachment. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 95(5), 965.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and

work-related performance: A meta-analysis.

Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 240–261.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (2003). Behavioral

management and task performance in organizations:

Conceptual background, meta‐analysis, and test of

alternative models. Personnel Psychology, 56(1), 155–

194.

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-

analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-

regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–

94.

van der Heijden, H. (2004). User Acceptance of Hedonic

Information Systems. MIS Quarterly, 28(4), 695–704.

bth.

Winter, D. G. (2001). The Motivational Dimensions of

Leadership: Power, Achievement, and Affiliation. In

Multiple Intelligences and Leadership (pp. 132–152).

Psychology Press.

Zhang, X., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking Empowering

Leadership and Employee Creativity: The Influence of

Psychological Empowerment, Intrinsic Motivation, and

Creative Process Engagement. Academy of

Management Journal, 53(1), 107–128.

E-DaM 2021 - Special Session on Empowering the digital me through trustworthy and user-centric information systems

182