Interoperability Maturity Assessment of the Digital Innovation Hubs

Concetta Semeraro

1,2 a

, Hervé Panetto

2b

, Gabriel da Silva Serapiao Leal

2,3,4 c

and

Wided Guédria

2,3

1

Department of Industrial and Management Engineering, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2

University of Lorraine, CNRS, CRAN, F-54000 Nancy, France

3

Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST), Luxembourg

4

Meritis, 5 – 7, rue d’Athènes, 75009 Paris, France

Keywords: Digital Innovation Hubs, Interoperability, CPS.

Abstract: In today’s manufacturing companies need to be able to join the Industry 4.0 paradigm and technologies. Often

companies, especially SMEs are not digitally ready. Digital Innovation Hubs (DIHs) are raising for

overcoming this problem. DIHs support companies providing services and digital technologies. However,

the critical challenge, for the development of the DIHs ecosystem is to assess the ability of the DIHs and

partners to interoperate together. DIH4CPS (Fostering DIHs for Embedding Interoperability in Cyber-

Physical Systems of European SMEs) is an Innovation Action (IA) receiving funding from the European

Union’s Horizon 2020 programme. DIH4CPS aims to create an embracing, interdisciplinary network of DIHs,

and solutions providers, focused on cyber-physical and embedded systems, interweaving knowledge and

technologies from different domains, and connecting regional clusters with the Pan-European expert pool of

DIHs. The paper presents the concepts, the ontology, and the prototype developed for DIH4CPS project with

the aim of assessing the Interoperability maturity of the DIHs and partner’s network.

1 INTRODUCTION

Industry 4.0 (I4.0) is a new paradigm of production

systems and it addresses transformable and

networked factories, depending on several drivers

such as modularity, virtualization, decentralization,

interoperability etc. and digital technologies

including big data analytics, autonomous robots and

vehicles, additive manufacturing, simulation,

augmented and virtual reality

etc. (Kagermann et al.,

2013). The potentialities of I4.0 paradigm are to

ensure a better flexibility and scalability of

manufacturing systems through the developments of

new information technologies (Dassisti and De

Nicolò, 2012), (Brettel et al., 2014).

The advances and the development of digital

technologies are largely responsible for the popularity

of the industry 4.0 paradigm and its potential use by

companies. Often SMEs lack IT competences and the

necessary technological and digital knowledge

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5152-0004

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5537-2261

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7121-7600

(Dassisti et al., 2017). To lower barriers, Digital

Innovation Hubs (DIH) are arising. Digital

Innovation Hubs are defined as: one-stop-shops that

help companies to become more competitive with

regard to their business/production processes,

products or services using digital technologies

(Smart Specialisation Platform, 2020). The role of

Digital Innovation Hubs (DIHs) is to help and support

companies, especially SMEs, in growing digital

competences, technologies and in providing

advanced training in digital technologies and skills.

DIHs provide services for the digitization of the

companies and, thereby, support the development of

the innovation ecosystem. The critical

factor/challenge, for the successful development of

the DIHs ecosystem and for the implementation of

Industry 4.0 technologies is to assess the ability of the

DIHs and partners to interoperate together.

Interoperability is the ability or the aptitude of two

systems that have to understand one another and to

function together (Chen et al., 2006). In the context

Semeraro, C., Panetto, H., Leal, G. and Guédria, W.

Interoperability Maturity Assessment of the Digital Innovation Hubs.

DOI: 10.5220/0010653800003062

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Innovative Intelligent Industrial Production and Logistics (IN4PL 2021), pages 67-74

ISBN: 978-989-758-535-7

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

67

of DIHs, assessing the DIHs and partners’ ability to

interoperate allow the identification and the

definitions of interoperability problems and

interoperability improvements (Panetto, 2007). The

interoperability assessment approaches can determine

DIHs’ interoperability strengths and weaknesses

defining actions for improving, avoiding or solving

interoperability problems (Guédria et al., 2015).

The paper aims to use and adapt the maturity model

developed in (Gabriel da Silva Serapiao Leal et al.,

2019) for defining how to assess and improve the

network interoperability between Digital Innovation

Hubs (DIHs) and partners. The paper presents the

basis for the Network Interoperability assessment and

improvement. In section 2 a focus is made on the state

of art of interoperability frameworks with the aim of

defining the DIHs interoperability requirements, the

DIHs interoperability barriers and DIHs

interoperability concerns in section 3. The ontology

of interoperability assessment is presented in section

4 while the interoperability assessment prototype in

section 5. At the end, the conclusions are presented.

2 STATE-OF-ART

Many researchers have proposed frameworks for

describing and assessing the Interoperability

providing and representing concepts, issues and

knowledge on Interoperability in a structured way

(Chen et al., 2006). The main discussed

interoperability frameworks are the European

Interoperability Framework (EIF), the Framework for

Enterprise Interoperability (FEI) and the Enterprise

Interoperability conceptualization (Gabriel da Silva

Serapião Leal et al., 2019).

The European Interoperability Framework (EIF)

provides a model to be applicable to all digital public

services. It is composed of four layers of

interoperability: legal, organizational, semantic and

technical (EIF, 2017). Legal interoperability refers to

the way in which organizations operating under

different legal conditions can work together.

Organizational interoperability defines how public

administrations align their business processes, and

responsibilities. Semantic interoperability denotes the

ability to exchange data and information between

applications and partners assuring a precise and

unambiguous meaning of the exchanged information.

Technical interoperability covers and includes

technical interoperability aspects and services

infrastructures.

The Framework for Enterprise Interoperability (FEI)

aims at structuring the concepts of the Enterprise

Interoperability domain and it is composed by three

dimensions: interoperability barriers, interoperability

concerns, and interoperability approaches (Chen et al.,

2006). The interoperability barriers refer to the

mismatches between systems which can obstruct the

sharing and exchanging of information. The

interoperability concerns regard enterprise levels

where interoperation can take place. Finally, the

interoperability approaches refer to the ways for

applying solutions and thus, removing

interoperability barriers. The FEI defines three major

interoperability barriers: Conceptual, Technological

and Organizational, four main Interoperability

concerns: Business, Process, Service and Data and

three approaches: federated, unified, and integrated.

The Enterprise Interoperability conceptualization

attempts to conceptualize the interoperability domain

(Panetto, 2007) defining the Ontology of

Interoperability (OoI) (Rosener et al., 2005),

(Ruokolainen et al., 2007). In the following years, the

OoI had been integrated with concepts from FEI

(Chen et al., 2006) and Enterprise-as-a-System

concepts proposing the Ontology of Enterprise

Interoperability (OoEI) (Chen et al., 2006). The OoEI

formally describes the system’s concepts and their

relations, regarding interoperability.

3 DIHs INTEROPERABILITY

REQUIREMENTS

A definite number of Interoperability Requirements

(IRs) for DIHs should be defined and satisfied

(Daclin et al., 2016) to achieve a higher quality of

interoperability (Guédria et al., 2015). To structure

the DIHs interoperability requirements we follow and

adapt the Maturity Model for Enterprise

Interoperability (MMEI) presented in (Guédria et al.,

2015). The MMEI is composed by the following six

components: the interoperability concerns, the

interoperability barriers, the interoperability area, the

maturity levels, the interoperability criteria, and the

best practices. Based on the FEI dimensions, the

MMEI defines four interoperability concerns

(Business, Process, Service, Data), three

interoperability barriers (Conceptual, Technological,

Organizational) and twelve interoperability area.

Those areas represent the crossing between an

interoperability barrier and an interoperability

concern e.g., Business-Conceptual, Service-

Technological etc. The MMEI defines five maturity

levels: Maturity Level 0- Unprepared; Maturity Level

1-Defined; Maturity Level 2-Aligned; Maturity Level

3-Organized; Maturity Level 4-Adaptive. The MMEI

present one criterion for each interoperability area for

each maturity level, totalizing forty-eight

interoperability criteria that can be rated using four

IN4PL 2021 - 2nd International Conference on Innovative Intelligent Industrial Production and Logistics

68

qualitative measurements: Not Achieved (NA),

Partially Achieved (PA), Largely Achieved (LA) and

Fully Achieved (FA). Furthermore, MMEI proposes

126 Best Practices that describe “what” should be

done to improve the interoperability performances

(Guédria et al., 2015).

In order to define the DIHs interoperability concerns,

we explored the Data-Business-Ecosystem-Skills-

Technology (D-BEST) reference model proposed in

(Sassanelli et al., 2020). The D-BEST reference

model configures and classify the DIHs services

portfolios on five main macro-classes: Data,

Business, Ecosystem, Skills and Technology. Each

class is composed by several types of services, as

shown in the Figure 1. The types of services represent

the main categories of services provided by the DIH

to its stakeholders in each of the five specific macro-

classes.

Data macro-class is important for exploiting digital

technologies potentialities. A DIH can provide five

types of services: data acquisition and sensing, data

processing and analysis, decision-making and data

sharing, including also physical-human action and

interaction.

Business macro-class intervenes in providing

services for supporting companies in business

training and education, project development, and in

facilitating access to different funding sources and

facilities.

Ecosystem macro-class is aimed at creating,

nurturing, expanding, and creating a community

around the DIHs that connects the members of the

innovation ecosystem providing services for sharing

best practices expertise.

Skills macro-class services allows to assess the skills

maturity of the companies that want to digitalize the

organization to set an adequate roadmap to empower

it and also to support the skill empowerment.

Technology macro-class provides hardware and

software services and solutions to technology

providers and technology users supporting the whole

lifecycle of digital technologies from conception and

idea generation to commercialization.

Figure 1: Services provided in the D-BEST reference

model. Extracted from (Sassanelli et al., 2020).

The DIHs Interoperability Requirements are defined

and organized according to the (ISO/IEC/IEEE

29148, 2011) recommendations for construction of a

requirement, the MMEI and the D-BEST reference

model. We integrate the European Interoperability

Framework (EIF) with the Framework for Enterprise

Interoperability (FEI) for defining the following

DIHs interoperability barriers: Conceptual,

Technological, Organizational and Legal. We adopt

the D-BEST reference model for defining the DIHs

interoperability concerns: Data, Business,

Ecosystem, Skills and Technology.

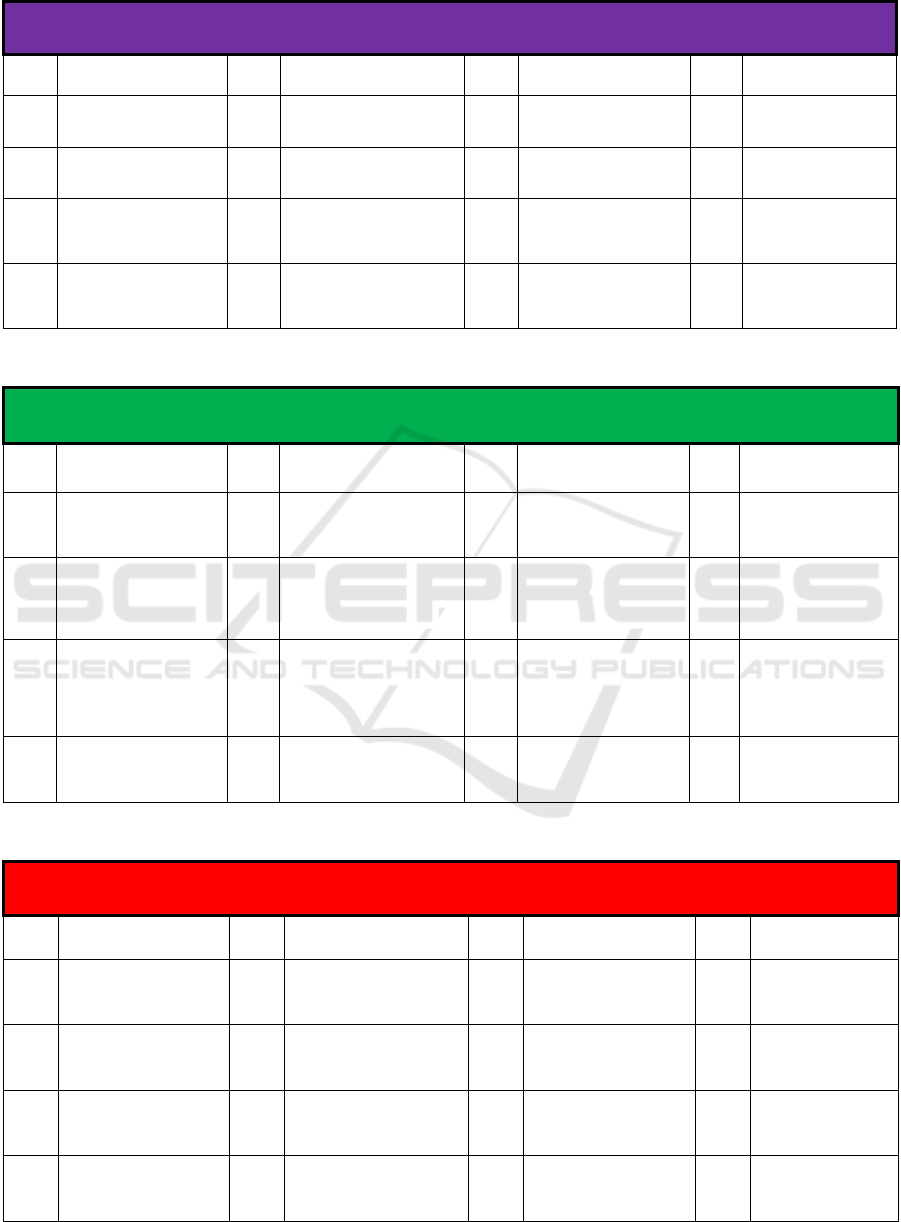

Table 1 to Table 5 present the DIHs Interoperability

requirements adapting also a set of interoperability

requirements presented in (Gabriel da Silva Serapiao

Leal et al., 2019), (Leal et al., 2020). Each table

present the interoperability concerns on the rows and

the interoperability barriers on the columns. The

interoperability area is the cross-section between an

Interoperability Barrier (Conceptual, Technological,

Organizational and Legal) and an Interoperability

Concern defined in D-BEST (Data, Business,

Ecosystem, Skills, and Technology, ) totalizing

twenty interoperability areas (Data-Conceptual,

Data-Technological, Data-Organizational, Data-

legal, Business-Conceptual, Business-Technological,

Business-Organizational, Business-Legal,

Ecosystem-Conceptual, Ecosystem-Technological,

Ecosystem-Organizational, Ecosystem Legal, Skills-

Conceptual, Skills -Technological, Skills-

Organizational, Skills -Legal, Technology-

Conceptual, Technology-Technological, Technology-

Organizational, Technology-Legal) and eighty

interoperability criteria.

Each requirement in the tables has an ID, which it is

composed of the first letter of the related

Interoperability Concern, the second letter of the

related Interoperability Barrier. These are followed

by the letter “R”, meaning that it is a requirement. The

related maturity level follows it. For example, the ID

“DCR1” represents the requirement related to the

Data concern and the Conceptual barrier from the

maturity level 1-Defined. The ID “BOR2” represents

the requirement related to the Business concern and

the Organizational barrier from the maturity level 2-

Aligned.

Interoperability Maturity Assessment of the Digital Innovation Hubs

69

Table 1: DIHs Interoperability Requirements for DATA Concern.

DATA

ID Conceptual ID Technological ID Organizational ID Legal

DCR1

Data models shall be

defined and documented

DTR1

Data acquisition, sensing,

storage and processing shall

be in place

DOR1

Responsibilities and

authorities shall be

defined and in place

DLR1

Data protection and

security shall be defined

DCR2

Standards shall be used for

alignment with other data

models

DTR2

Automated access to data

based on standard protocols

shall be in place

DOR2

Rules and methods for

data management shall be

in place

DLR2

Rules and methods for

data security shall be in

place

DCR3

Meta-modelling shall be

done for multiple data

model mappings

DTR3

Remote access to databases

shall be possible for

applications and shared data

shall be available

DOR3

Personalized data

management for different

partners shall be in place

DLR3

Meta-modelling shall be

done for data security

DCR4

Data models shall be

adaptive

DTR4

Direct database exchanges

capability and full data

conversion tool(s) shall be in

p

lace

DOR4

Adaptive data

management rules and

methods shall be in place

DLR4

Adaptive data

security rules and

methods shall be in

p

lace

Table 2: Dihs Interoperability Requirements for BUSINESS Concern.

BUSINESS

ID Conceptual ID Technological ID Organizational ID Legal

BCR1

Business Models, Methods

and Tools, Business

Operations Modelling shall

b

e defined and documented

BTR1

Basic IT infrastructure be in

place shall

BOR1

Organization structure shall

be defined and in place

BL1

Access to founding

sources and financial

issues shall be defined

and documente

d

BCR2

Standards shall be used for

alignment with other

business models, Methods

and Tools, Business

O

p

erations Modellin

g

BTR2

Standard and configurable

IT infrastructures shall be

used

BOR2

Standards shall be used for

alignment with other

partners

BL2

Standards shall be

defined and used to

provide legal and fiscal

advices

BCR3

Business Model, Methods

and Tools, Business

Operations Modelling shall

be designed for multi

partnership and

collaborative DIHs

BTR3 IT infrastructure shall be open BOR3

Organization structure and

collaboration shall be

flexible

BL3

Technical and legal

assistance should be

provided to facilitation

the access to different

funding sources

BCR4

Business model, Methods

and Tools, Business

Operations Modelling shall

b

e ada

p

tive

BTR4

IT infrastructure adaptive

shall be

BOR4

Organization -demand

business shall be agile for

BL4

Legal services should be

adaptative

Table 3: DIHs Interoperability Requirements for ECOSYSTEM Concern.

ECOSYSTEM

ID Conceptual ID Technological ID Organizational ID Legal

ECR1

Service provided to the

ecosystem shall be

defined and documented

ETR1

Applications/services shall be

connectable and ad hoc

information

exchan

g

e shall be

p

ossible

EOR1

Ecosystem responsibilities

and authorities shall be

defined and put in place

ELR1

Ecosystem governance

shall be defined and

documented

ECR2

Standards shall be used for

alignment with other

partners and DIHs

ETR2

Standardize and configurable

service architecture(s) and

interface(s) shall be available

EOR2

Procedures for ecosystem

interoperability shall be

in place

ELR2

Procedures for

ecosystem governance

shall be defined and in

p

lace

ECR3

Meta-modelling shall be

done for multiple service

model mappings

ETR3

Automated services discovery

and composition shall be

possible and shared

a

pp

lications shall be in

p

lace

EOR3

Collaborative services

and application

management shall be in

p

lace

ELR3

Ecosystem

collaboration shall be

in place

ECR4

Service modelling shall be

adaptive

ETR4

Dynamically composable

services and networked

applications shall be

in

p

lace

EOR4

Dynamic service and

application management

rules and methods shall

b

e in

p

lace

ELR4

Procedures for

ecosystem governance

shall adaptative

IN4PL 2021 - 2nd International Conference on Innovative Intelligent Industrial Production and Logistics

70

Table 4: DIHs Interoperability Requirements for SKILLS Concern.

SKILLS

ID Conceptual ID Technological ID Organizational ID Legal

SCR1

Skill and rules shall be

defined and documented

STR1

Assessment of human skills

maturity shall be defined and

documented

SOR1

Responsibilities

and authorities shall be

defined and put in place

SLR1

Skills governance shall

be defined and

documented

SCR2

Standards shall be defined

for assessing the company

readiness for Industry 4.0

STR2

Standard process tools and

platforms shall be available

SOR2

Procedures for skills

exchange shall be in

place

SLR2

Procedures for Skills

governance and

exchange shall be

defined and in

p

lace

SCR3

Standard shall be defined

based on the maturity

model assessment

STR3

Platform(s) and tool(s) for

collaborative training shall be

available

SOR3

Organization of dedicated

human up-skilling, re-

skilling trainings and

worksho

p

s shall be in

p

lace

SLR3

Intellectual properties

shall be defined and in

place

SCR4

Standard shall be defined

for supporting the

knowledge-transfer through

internal channels, structure

contacts and collaborations

STR4

Dynamic and adaptive tool(s)

shall be available

SOR4

Support for knowledge-

transfer through internal

channels, structure contacts

and collaborations shall be

ada

p

tative

SLR4

Procedures for Skills

governance shall

adaptative

Table 5: DIHs Interoperability Requirements for TECHNOLOGY Concern.

Technology

ID Conceptual ID Technological ID Organizational ID Legal

TCR1

Technologies shall be

defined and documented

TTR1

IT devices shall support

processes and ad hoc

exchange of process

information shall be

p

ossible

TOR1

Responsibilities

and authorities shall be

defined and put in place

TLR1

Technology

governance shall be

defined and

documente

d

TCR2

Standards shall be used

for alignment of new skills

TTR2

Standard process tools and

platforms shall be available

TOR2

Procedures for technologies

interoperability shall be in

place

TLR2

Procedures for

technology governance

shall be defined and in

p

lace

TCR3

Meta-modelling shall be

done for multiple

process model mappings

TTR3

Platform(s) and tool(s) for

collaborative execution of

processes shall be available

TOR3

Cross-enterprise/DIHs

collaborative processes

management shall be in

p

lace

TLR3

Technologies

intellectual properties

shall be defined and in

p

lace

TCR4

Technologies modelling

shall be done for dynamic

re-engineering

TTR4

Dynamic and adaptive tool(s)

and engines shall be

available

TOR4

Real-time monitoring of

processes, adaptive

procedures shall be in place

TLR4

Procedures for

technology governance

shall adaptative

4 ONTOLOGY OF

INTEROPERABILITY

ASSESSMENT

To assess the interoperability degree between DIHs,

we use and adapt the Ontology of Interoperability

Assessment (OIA) presented in (Gabriel da Silva

Serapiao Leal et al., 2019), (Leal et al., 2020).

(Gabriel da Silva Serapiao Leal et al., 2019) propose

a conceptual model for illustrating the concepts and

relations of the OIA. This model serves as the basis

for implementing the ontology using Protégé tool.

The OIA presents an architecture containing three

different layers: the Assessment Meta-model, the

Interoperability Assessment Meta-model and the

Implementation.

The Assessment Meta-model contains the general

concepts of an assessment and defines a general

representation of an assessment. The model is divided

into two cores: the systemic core, which allows the

design of systems to be assessed, and the assessment

core that describes the concepts related to an

assessment allowing the design of different kinds of

assessment.

The Interoperability Assessment Meta-Model is an

instantiation of the Assessment Meta-model, based on

the interoperability assessment.

Finally, the Implementation is the instantiation of the

real world, i.e., it represents the real assessed system

and the applied assessment model.

Interoperability Maturity Assessment of the Digital Innovation Hubs

71

We adapted the OIA to DIHs assessment populating

the ontology with the fixed instances as shown in

Figure 2. These instantiations include the following

concepts:

Requirement with the set of interoperability

requirements defined in section 3 based on D-

BEST reference model (Sassanelli et al., 2020)

and the MMEI defined in (Guédria et al., 2015).

Problem with the interoperability barriers

described in the Framework for Enterprise

Interoperability (FEI) (Chen et al., 2006) and in

the European Interoperability Framework (EIF)

(EIF, 2017).

Solution with the 126 best practices defined in

MMEI (Guédria et al., 2015), (ISO 11354-2,

2015) and the catalogue of DIHs competences.

Quality Attribute with the sixteen

interoperability areas (Data-Conceptual, Data-

Technological, Data-Organisational, Data-legal,

Business-Conceptual, etc) presented in section 3.

Quality with the five maturity levels

(Unprepared, Defined, Aligned, Organised and

Adaptive) defined in MMEI (Guédria et al.,

2015).

Figure 2: Ontology of Interoperability Assessment.

Adapted from (Gabriel da Silva Serapiao Leal et al., 2019).

5 DIHs INTEROPERABILITY

REQUIREMENTS

The prototype architecture, its functionalities, and the

concerned users are developed based on the results

discussed in section 3 and the ontology presented in

section 4. The prototype has the objective to support

the DIHs assessment process. An overview of the

users, assessment process and prototype relations are

illustrated in Figure 3. The assessment process is

composed by the activities carried out by the Lead

assessor and the Assessor. The Lead assessor

manages the evaluation workflow and the system to

structure and finalize the entire assessment. He

oversees creating and editing the assessment. The

assessors (in this context the DIHs and partners’

network) are responsible for completing and editing

their assigned assessment by entering their

evaluations.

Figure 3: Screenshot of the DIHs Interoperability

Assessment Tool.

When the lead assessor creates the assessment, he

sends a notification to the concerned assessors

(DIHs). The DIHs, then, can log in their accounts and

complete the concerned interoperability assessment

evaluating the interoperability concerns based on the

interoperability layers (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Screenshot of the DIHs assessment scope:

Interoperability Barriers and Concerns.

The rating process is illustrated in Figure 5. The

interoperability requirements presented in table 1-5 in

section 3 are written in the form of questions to

facilitate their evaluations. In this interface of the

prototype, the assessors (DIHs) rate the requirements,

related to the interoperability area: Conceptual barrier

and Business concern, using the maturity levels: “Not

Achieved (NA)”, “Partially Achieved (PA)”,

“Largely Achieved (LA)” and “Fully Achieved

(FA)”. Comments and evidence (e.g., documents,

images, etc.) can also be added.

Once the assessors complete their assessments, they

send a notification to the lead assessor. The latter,

then, aggregates the requirement ratings provided.

Figure 6 illustrates the summary concerning the rates

related to requirement from the Business-Concern. In

the final step, the lead assessor launches the option

“validate” to finalize the results.

IN4PL 2021 - 2nd International Conference on Innovative Intelligent Industrial Production and Logistics

72

Figure 5: Screenshot of the DIHs assessment: Requirement

rating.

Figure 6: Screenshot of the DIHs assessment: Assessment

Summary.

The prototype has the objective to assess the DIHs

interoperability maturity. For example, if it assesses

unprepared level (maturity level 0) means that the

DIH does not have an appropriate environment for

developing and maintaining interoperability. For

achieving the next level (maturity level 1), the

concerned DIH should focus on improving the

conceptual/ technological/ organizational and legal

requirements related to data/ business/ ecosystem/

skills/ technology concerns.

A list of best practices and competences based on the

maturity level and criteria evaluation is automatically

generated in the tool and presented in a report that

contains the determined DIHs and partners’ maturity

level, the final rating of each evaluation criteria, the

identified problems, and associated solutions (best

practices and DIHs competences)

6 CONCLUSIONS

The paper aims at defining the DIHs interoperability

requirements adapting the Ontology of

Interoperability Assessment. In section 2 we have

presented an overview of the state of art of

interoperability assessment frameworks. First, we

have explored the European Interoperability

Framework (EIF), the Framework for Enterprise

Interoperability (FEI) and the Enterprise

Interoperability conceptualization. Second, we have

reviewed the Interoperability exploring the Maturity

Model for Enterprise Interoperability (MMEI), and

the D-BEST reference to model to define the DIHs

interoperability barriers and the DIHs interoperability

concerns. The DIHs interoperability requirements

have been presented and listed in section 3. In section

4 we have described the Ontology of Interoperability

Assessment. The proposed architecture is composed

by three layers: the Assessment Meta-model, the

Interoperability Assessment Meta-model and the

Implementation. Finally, in section 5 we have

presented the interoperability assessment prototype

developed from the ontology described in section 4.

The prototype has the objective to ease the

assessment process by providing automatic steps such

as the requirement rate and the evaluation report

generation.

This paper presents the first version of the

interoperability maturity model prototype, which will

have major additional improvements. These updates

will concern mainly the integration of the maturity

model and the prototype. Currently, the prototype is a

stand-alone Java application linked to a MySQL

database. As it is intended to be a feature/service of

the DIH4CPS Portal, it should be easily transformed

in a web-based feature available for all DIH4CPS

partners but also the whole DIH4CPS network.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has received funding from the European

Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation

programme under grant agreement No 872548.

REFERENCES

Brettel, M., Friederichsen, N., Keller, M., Rosenberg, M.,

2014. How virtualization, decentralization and network

building change the manufacturing landscape: An

Industry 4.0 Perspective. International journal of

mechanical, industrial science and engineering 8, 37–44.

Chen, D., Dassisti, M., Elvesaeter, B., Panetto, H., Daclin,

N., Jaekel, F.-W., Knothe, T., Solberg, A., Anaya, V.,

Gisbert, R.S., 2006. DI. 2: Enterprise Interoperability-

Framework and knowledge corpus-Advanced report.

Daclin, N., Daclin, S.M., Chapurlat, V., Vallespir, B., 2016.

Writing and verifying interoperability requirements:

Application to collaborative processes. Computers in

Industry 82, 1–18.

Dassisti, M., De Nicolò, M., 2012. Enterprise integration and

economical crisis for mass craftsmanship: a case study of

an Italian furniture company, in: OTM Confederated

Interoperability Maturity Assessment of the Digital Innovation Hubs

73

International Conferences" On the Move to Meaningful

Internet Systems". Springer, pp. 113–123.

Dassisti, M., Panetto, H., Lezoche, M., Merla, P., Semeraro,

C., Giovannini, A., Chimienti, M., 2017. Industry 4.0

paradigm: The viewpoint of the small and medium

enterprises, in: 7th International Conference on

Information Society and Technology, ICIST 2017. pp.

50–54.

EIF, 2017. European Interoperability Framework -

Implementation Strategy. Annex II of to the

communication from the commission to the European

parliament, the council, the European economic and

social committee and the committee of the regions.

Brussels.

Guédria, W., Naudet, Y., Chen, D., 2015. Maturity model

for enterprise interoperability. Enterprise Information

Systems 9, 1–28.

ISO/IEC 29148, 2011. ISO/IEC 29148: System and

software engineering – Life cycle processes –

Requirements Engineering. ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 7.

Geneva.

ISO 11354-2, 2015. ISO 11354-2:2015 - Advanced

automation technologies and their applications --

Requirements for establishing manufacturing enterprise

process interoperability -- Part 2: Maturity model for

assessing enterprise interoperability. ISO/TC 184/SC 5.

Kagermann, H., Helbig, J., Hellinger, A., Wahlster, W.,

2013. Recommendations for implementing the strategic

initiative INDUSTRIE 4.0: Securing the future of

German manufacturing industry; final report of the

Industrie 4.0 Working Group. Forschungsunion.

Leal, Gabriel da Silva Serapiao, Guédria, W., Panetto, H.,

2019. An ontology for interoperability assessment: A

systemic approach. Journal of Industrial Information

Integration 16, 100100.

Leal, Gabriel da Silva Serapião, Guédria, W., Panetto, H.,

2019. Interoperability assessment: A systematic

literature review. Computers in Industry 106, 111–132.

Leal, G., Guédria, W., Panetto, H., 2020. A semi-automated

system for interoperability assessment: an ontology-

based approach. Enterprise Information Systems 14,

308–333.

Panetto, H., 2007. Towards a classification framework for

interoperability of enterprise applications. International

Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing 20,

727–740.

Rosener, V., Naudet, Y., Latour, T., 2005. A Model

Proposal of the Interoperability Problem., in: EMOI-

INTEROP.

Ruokolainen, T., Naudet, Y., Latour, T., 2007. An ontology

of interoperability in inter-enterprise communities, in:

Enterprise Interoperability II. Springer, pp. 159–170.

Sassanelli, C., Panetto, H., Guedria, W., Terzi, S.,

Doumeingts, G., 2020. Towards a reference model for

configuring services portfolio of digital innovation

hubs: the ETBSD model, in: Working Conference on

Virtual Enterprises. Springer, pp. 597–607.

Smart Specialisation Platform, 2020. Digital Innovation

Hubs [WWW Document]. Smart Specialisation

Platform. URL https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu

(accessed 6.4.21).

IN4PL 2021 - 2nd International Conference on Innovative Intelligent Industrial Production and Logistics

74