Reframing the Fake News Problem: Social Media Interaction Design to

Make the Truth Louder

Safat Siddiqui and Mary Lou Maher

College of Computing and Informatics, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, NC, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Fake News, Misinformation, Intervention, Combat, Interaction, Design Principle, Social Media.

Abstract:

This paper brings a new perspective in social media interaction design that reframes the problem of misinfor-

mation spreading on social platforms as an opportunity for UX researchers to design interactive experiences

for social media users to make the truth louder. We focus on users’ interaction tendencies to promote 2 target

behaviors for the social media users: 1. Users interact more with credible helpful information, and 2. Users

interact less with harmful unverified information. The existing platform-based interventions assist users in

getting context and making informed decisions about the information they consume and share on the platform,

independently of users’ interaction tendencies on social platforms. But social media users exhibit different

interaction behaviors - active users on social platforms tend to interact with content and other users often. In

contrast, passive users prefer to avoid the interactions that produce digital footprints. This paper presents a

theoretical basis and 3 design principles to pursue the new research perspective - it builds on the Fogg behav-

ior model (FBM) to transform users’ interaction behaviors to mitigate the fake news problem, describes users’

active-passive interactions tendencies as a basis for design, and presents the 2 target interaction behaviors to

prompt on social platforms.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper presents a shift in focus for the mitigation

of fake news that has the goal to encourage social me-

dia users to share more credible information rather

than solely relying on stopping the spread of misin-

formation. Misinformation, one type of fake news

that refers to unintentional spreading of false infor-

mation, is responsible for increasing polarization and

the consequential loss of trust in science and media

(Lewandowsky et al., 2017). To reduce the spread

of misinformation, social media platforms are remov-

ing the accounts that spread misleading information

and the posts that contain false information. In ad-

dition to that effort, platforms are introducing new

indicators that facilitate the process of getting con-

textual information about posts that have question-

able veracity. The purpose of the indicators is to as-

sist users’ information verification process while con-

suming or before sharing the information with other

users. Though the intention of these indicators is to

minimize the spread of questionable content [(Smith,

2017); (Roth and Pickles, 2020); (Nekmat, 2020)],

the design aspects do not address users’ interaction

behaviors to leverage the interaction tendencies in

distributing credible information. In this paper, we

present users’ active-passive interactions tendencies

as the basis for design and provide 3 principles of

designing social media interaction that combat fake

news with a focus on making the truth louder on so-

cial platforms.

A focus on making the truth louder on social plat-

forms means that the interaction designs nudge users

toward distributing credible information and limiting

the spread of unverified information. Nudges, in the

form of suggestions or recommendations, intend to

steer users’ behaviors in particular directions with-

out sacrificing users’ freedom of choices [(Thaler and

Sunstein, 2009); (Acquisti et al., 2017)]. We iden-

tify that users’ interaction abilities on social media

can be described in the range from active to passive

- active users have a strong tendency to interact with

content and other users, whereas passive users have

the tendency to refrain from interactions [(Gerson

et al., 2017); (Chen et al., 2014); (Trifiro and Gerson,

2019)]. Users’ interaction behaviors could transform

overtime. Shao (Shao, 2009) has suggested that users

initially consume content and eventually start partic-

ipating on the platform and produce content. The

Reader-to-Leader Framework (Preece and Shneider-

158

Siddiqui, S. and Maher, M.

Reframing the Fake News Problem: Social Media Interaction Design to Make the Truth Louder.

DOI: 10.5220/0010658200003060

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2021), pages 158-165

ISBN: 978-989-758-538-8; ISSN: 2184-3244

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

man, 2009) indicates the evolution of a user from a

reader to a leader. This paper builds on our under-

standing of the active-passive continuum presented in

[ (Gerson et al., 2017); (Shao, 2009); (Preece and

Shneiderman, 2009)] to develop a theoretical basis for

nudging user behavior to adopt the 2 target interaction

behaviors that combat fakes news by making the truth

louder:

• Target Behavior 1 (TB1): Users interact to in-

crease the spread of verified and credible infor-

mation.

• Target Behavior 2 (TB2): Users interact to re-

duce the spread of unverified and questionable in-

formation.

We present 3 principles for designing social media

interaction that are grounded on users’ active-passive

tendencies and intend to increase users’ likeliness of

performing the 2 target behaviors. The design princi-

ples are inspired by the Fogg Behavior Model (FBM)

(Fogg, 2009) that suggests a change of behavior hap-

pens when individuals have 2 factors: 1. the abil-

ity to change the behaviors and 2. the motivation to

change the behaviors and overlays 3 types of prompts,

1. Signal, 2. Facilitator, and 3. Spark. In our design

principles, the factor ‘ability’ refers to individuals’ in-

teraction tendencies and the factor ‘motivation’ refers

to individuals’ motivation to contribute in making the

truth louder. The 3 design principles of social media

interaction for combating misinformation are:

1. Awareness on Making the Truth Louder: The

goal of this design principle is to remind users and

nudge their attention to perform the target behav-

iors that can make the truth louder. This design

principle is inspired from the Signal prompt in

FBM (Fogg, 2009) and appeals to social media

users who possess high ability to perform the be-

haviors and high motivation to contribute to mak-

ing the truth louder.

2. Guidance on Making the Truth Louder: The

goal of this design principle is to provide users the

necessary interaction supports for performing tar-

get behaviors that lead to making the truth louder.

This design principle is inspired from the Facil-

itator prompt in FBM (Fogg, 2009) and appeals

to social media users who have low ability to per-

form the target behaviors but possess a high moti-

vation to contribute to making the truth louder.

3. Incentive on Making the Truth Louder: The

goal of this design principle is to provide incen-

tives and encourage users to perform the target

behaviors that can make the truth louder. This de-

sign principle is inspired from the Spark prompt

in FBM (Fogg, 2009) and appeals to social media

users who have the ability to perform the inter-

action behaviors but are not highly motivated to

participate in making the truth louder.

The organization of this paper is as follows: Sec-

tion 2 presents the related work and describes how the

design principles contribute to the research on com-

bating fake news. In Section 3, we discuss the dif-

ferences between active and passive users’ interaction

behavior and describe the connection of users’ inter-

action tendencies with the target behaviors that can

make the truth louder. Section 4 presents the 3 design

principles, provide prototypes to explain the princi-

ples and discusses the existing social media interven-

tions in the lens of these design principles. Finally,

we conclude the paper with a discussion of future re-

search for making the truth louder.

2 RELATED WORK

Social media companies are taking steps to reduce the

spread of fake news, such as misinformation (unin-

tentional misleading information) and disinformation

(intentional misleading information). They develop

algorithms and work with third parties to detect fake

content and the accounts who spread those fake in-

formation [(Rosen, 2021); (Rosen and Lyons, 2019)].

Platforms such as Facebook and Twitter remove fake

content and the accounts that display inauthentic ac-

tivities [(Roth and Harvey, 2018); (Gleicher, 2019)].

To reduce the spread of unverified information, the

platforms demote flagged posts and the content that

are detected to be spam or clickbait [(Babu et al.,

2017); (Crowell, 2017)]. In the research communi-

ties, a wide range of algorithms have been developed

to detect fake information by analyzing textual fea-

tures, network structure, and developing propagation

models [(Kumar and Shah, 2018)].

Despite the ongoing development of sophisticated

algorithms, misleading information is still posted and

spread on the platforms. Researchers have investi-

gated effective ways of correcting the misinformation

that has already spread, and identified the negative ef-

fects of fake information on individuals due to cog-

nitive biases, such as confirmation bias, continued in-

fluence, backfire effect [(Lewandowsky et al., 2017);

(Lewandowsky et al., 2012); (Mele et al., 2017)].

Studies have been conducted to understand how users

seek and verify the credibility of news on social media

[(Flintham et al., 2018); (Torres et al., 2018); (Bentley

et al., 2019); (Morris et al., 2012)], how they interact

with misinformation (Geeng et al., 2020), why and

how users spread fake news [(Marwick, 2018); (Star-

bird et al., 2018); (Starbird, 2017); (Arif et al., 2016)].

Reframing the Fake News Problem: Social Media Interaction Design to Make the Truth Louder

159

Those investigations provide a broader context of the

problem of fake news spreading on social media and

add value in developing communication and mitiga-

tion strategies for platform-based interventions.

The platform-based interventions create indicators

that assist users in making informed decisions on their

choices of information consuming and information

sharing on the platform. For example, Facebook pro-

vides an information (‘i’) button that shows details

about the source website of an article, and places

‘Related Articles’ next to the information that seems

questionable to the platform [(Hughes et al., 2018);

(Su, 2017); (Smith, 2017)]. Twitter warns users about

the information that could be misleading and harm-

ful, and directs users to credible sources (Roth and

Pickles, 2020); Twitter also introduces a community-

driven approach, Birdwatch, to identify misleading

information on the platform (Coleman, 2021). In

addition to the platform-based attempts, there exist

browser extensions [(Bhuiyan et al., 2018); (Perez

et al., 2020)] and media literacy initiatives [(Roozen-

beek and van der Linden, 2019); (Grace and Hone,

2019)] to assist users in identifying the credibility of

content.

However, the primary focus of existing design in-

terventions is to communicate to users about the cred-

ibility of the content. In this paper, we shift the focus

to create intervention designs that consider the differ-

ence between active and passive users and are adap-

tive to individual’s interaction tendencies. Preece et

al. (Preece and Shneiderman, 2009) have also sug-

gested the importance of various interface supports to

increase participation more generally, where our fo-

cus is on increasing participation to make the truth

louder. We provide 3 design principles for the UX re-

searchers to explore the design ideas with respective

design goals and address users’ active-passive ten-

dencies to increase users’ participation for combating

fake news.

3 TARGET BEHAVIORS FOR

THE USERS WITH DIFFERENT

INTERACTION TENDENCIES

To make the truth louder, our design principles focus

on promoting 2 target behaviors for social media users

possessing interaction tendencies ranging from active

to passive. In this section, we present the relationship

between 2 target behaviors and users’ interaction ten-

dencies on social platforms.

3.1 Users’ Interaction Tendencies on

Social Platforms

Social media users have different interaction tenden-

cies on social platforms. Some users play an active

role by participating in various interactions, such as

posting comments, sharing content and creating their

own content and posts, uploading photos and videos.

These users are known as active users [(Khan, 2017);

(Chen et al., 2014)]. Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2014)

identified 25 active users’ interactions on social me-

dia and categorized those into 4 dimensions: Content

Creation, Content Transmission, Relationship Build-

ing, and Relationship Maintenance. Conversely, some

social media users do not like to interact with so-

cial media that produces a digital footprint - they are

known as passive users [(Gerson et al., 2017);(Non-

necke and Preece, 1999)]. Passive users prefer to

seek information and entertainment on social plat-

forms and they are more involved in the interactions

that are required to consume information - that type

of interactions can be identified as Content Consump-

tion. According to (Shao, 2009), users first consume

content, then start participating and become the mem-

bers who can produce content. Shao’s (Shao, 2009)

suggestion indicates that users are initially involved in

the interactions related to content consumption, and

over time, users start using interaction items related

to the dimension of relationship building, relationship

maintenance, and content transformation. When users

develop relationships with other users and get habit-

uated to interacting with content, they proceed using

interaction items related to content creation.

The passive and active users have different pref-

erences towards the interaction dimensions because

of their interaction tendencies [(Gerson et al., 2017),

(Trifiro and Gerson, 2019)]. Though the users are

similar in the dimension of content consumption,

the interaction preference between active and passive

users starts to differ in other dimensions of interac-

tions, such as content creation and content transmis-

sions. In comparison to active users, passive users

have less preference for interaction items that are

not related to content consumption. The design af-

fordance that helps users to get context and verify

information are related to the interactions of con-

tent consumption dimension, where interaction pref-

erences between active and passive users remain sim-

ilar. We focus on the interactions of content transmis-

sions where active users are more likely to participate

than passive users and provide 3 design principles of

social media interaction adaptive to users’ interaction

tendencies.

CHIRA 2021 - 5th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

160

3.2 Difference between Users’ Abilities

to Perform the Target Behaviors

The ability to perform the 2 target behaviors will be

different for the users due to their interaction tenden-

cies. Active and passive users on social media demon-

strate the opposite ability because of their online in-

teraction tendencies, making target behavior 1 (TB1)

easier for active users but difficult for passive users,

and target behavior 2 (TB2) easier for passive users

but difficult for active users.

The ability to contribute to the spread of verified

information (TB1) demands interactions with content

and other social media users - such ability is high for

the active users but low for the passive users. Due to

active users’ natural inclination, they are habituated

to perform high levels of interactions, such as shar-

ing information with other users, making comments,

or sending love/like reactions to the content - these

interactions contribute to the distribution of verified

information. But passive users hesitate to perform

such interactions and have low levels of interactions

on social platforms, which makes adopting the target

behavior 1 challenging for passive users.

In contrast, limiting the spread of unverified in-

formation (TB2) is easier for passive users to adopt

compared to active users as it requires users to interact

less with the unverified content. For target behavior 2,

passive users get an advantage as they have the gen-

eral tendency to interact less with social media con-

tent. However, active users have to be reflective about

their activities on social platforms so that they do not

interact with any unverified content because of their

natural behavioral tendencies, which makes adopting

target behavior 2 harder for active users.

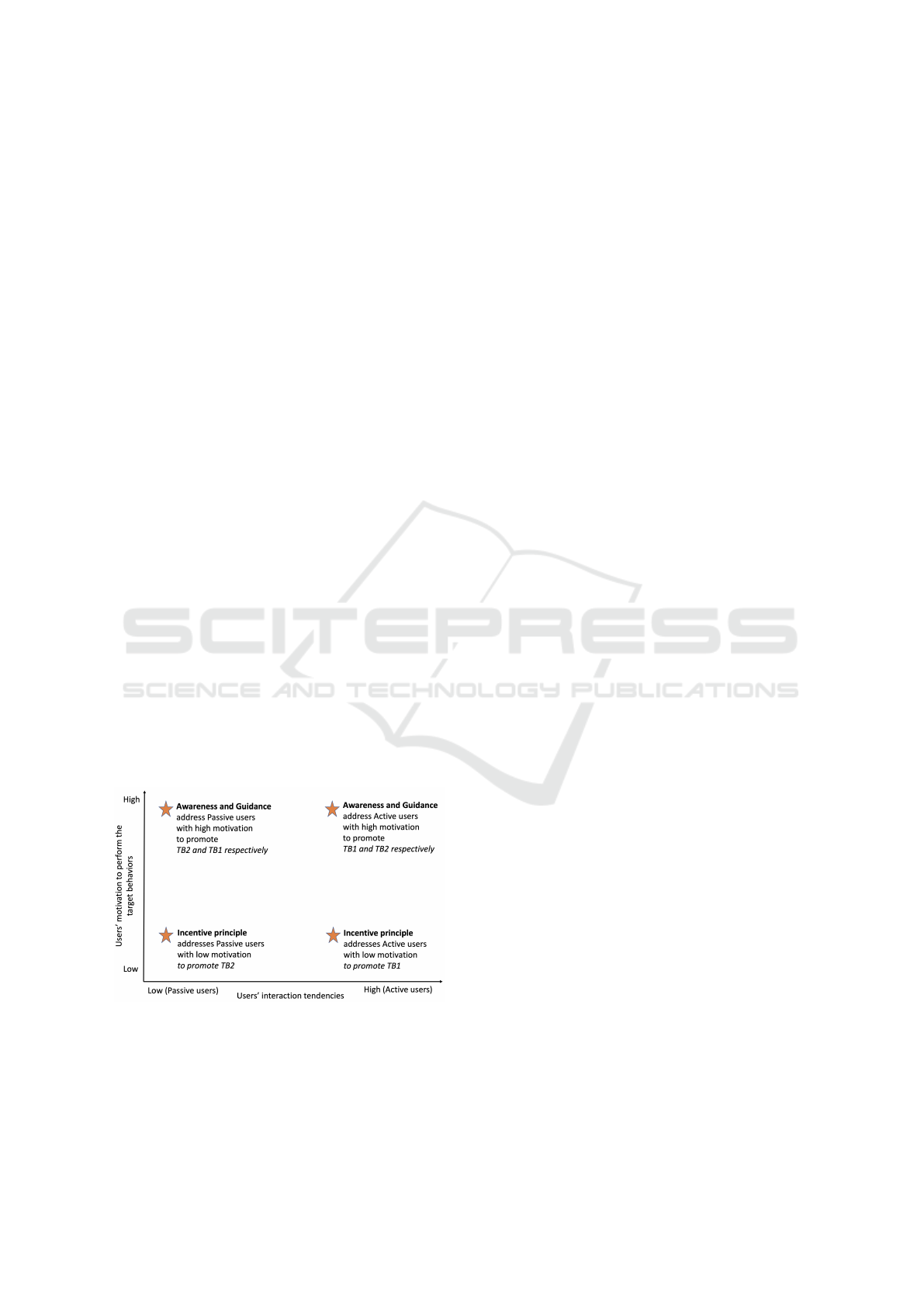

Figure 1: The design principles addresses the differences

between active and passive users to perform the target be-

haviors.

The design principles address the differences be-

tween active and passive users’ online interaction ten-

dencies to direct their interactions to make the truth

louder on social media, as illustrated in Figure 1. Ac-

tive users have high interaction abilities, and passive

users have low interaction abilities. As users’ inter-

actions (e.g., shares, comments, likes) on social plat-

forms lead to the distribution of the content in that

platform, the principles intend to assist active users in

adopting the target behavior to interact only with the

credible information and not to interact with unveri-

fied or questionable information. Similarly, the prin-

ciples intend to support passive users to increase their

interactions with credible information that can make

the truth louder on social platforms.

4 DESIGN PRINCIPLES THAT

ADDRESS USERS’

INTERACTION TENDENCIES

We present 3 design principles that address users’ in-

teraction tendencies: Awareness, Guidance, and In-

centive on making the truth louder. In this section, we

describe the design principles that appeal to the users

of different levels of interaction abilities and motiva-

tion, and discuss the existing design interventions in

reference to these principles.

4.1 Awareness on Making the Truth

Louder

The purpose of the Awareness design principle is to

assist social media users in recognizing verified and

unverified content that appears in their social media

feeds and remind users to perform the target behavior

that can make the truth louder. This design principle

is a Signal prompt in the FBM (Fogg, 2009) that is ef-

fective for individuals who have high motivation and

high ability to perform the target behavior. When ac-

tive users on the platform have the motivation to par-

ticipate in making the truth louder, they can respond

positively to the intervention designs that follow the

Awareness design principle promoting the target be-

havior 1. Likewise, passive users can respond easily

to the interventions that follows the Awareness design

principle to promote the target behavior 2 - requesting

limited interactions with the unverified and question-

able content.

Most of existing interventions can be described

using the Awareness design principle as the focus

of these interventions is to inform users about the

context and validity of the information. For exam-

ple, social media platforms, such as Facebook and

Twitter, provide related fact-checkers’ information so

that users can get the context of the information.

Reframing the Fake News Problem: Social Media Interaction Design to Make the Truth Louder

161

Facebook shows an indicator to related articles when

the platform detects any questionable content [(Su,

2017); (Smith, 2017)]. Twitter warns users if the plat-

form identifies any harmful content (Roth and Pick-

les, 2020). The accuracy nudging intervention (Pen-

nycook et al., 2020) draws users’ attention to the

accuracy of the content, and NudgeFeed (Bhuiyan

et al., 2018) applies visual cues to grab users’ at-

tention to the credibility of the information source -

whether the information source is mainstream or non-

mainstream. These platform-based interventions edu-

cate users about the context of the information when

users are involved in content consumption interac-

tions. Some interventions, such as Facebook, alert

users when they interact to share any questionable

content (Smith, 2017). These interventions follow the

Awareness design principle as the purpose is to make

users aware of the context before they share the infor-

mation on social media.

To describe the Awareness design principle, we

present a design prototype that promotes the target

behavior 1, illustrated in Figure 2. The prototype

use the standard signifiers ‘Like’, ‘Comment’, and

‘Share’ buttons of Facebook that signal users can per-

form interactions to like the information, make com-

ments about that information, and share that informa-

tion with other users. The credible information in

Figure 2 is collected from (Pennycook et al., 2020)

study, and we add ‘More information about this link’

and ‘Related Articles’ sections that assist users in

getting the context of the content. Figure 2 follows

the Awareness design principle that uses texts in the

‘More information about this link’ section to commu-

nicate with users about the credibility of information

and information source, and have related fact-checked

articles in ‘Related Articles’ section to provide more

contextual information. This prototype focuses on in-

forming the active users about context of the infor-

mation so that the subset of active users who posses

the motivation to contribute in making the truth louder

become aware to share the verified information.

Figure 2: Prototype describing the Awareness design prin-

ciple for promoting target behavior 1.

4.2 Guidance on Making the Truth

Louder

The purpose of the Guidance design principle is to

simplify the interactions for the users to increase their

ability to interact on social platforms and educate

users about the interactions that can lead to the distri-

bution of credible information and limit the spread of

unverified harmful information. This design principle

is a Facilitator prompt in the FBM (Fogg, 2009) that

is effective for individuals who have high motivation

but low ability to perform the target behaviors. This

design principle focuses on promoting target behav-

ior 1 among passive users by simplifying the interac-

tion steps for them that assist their interactions for dis-

tributing credible information. Likewise, this design

principle can promote target behavior 2 among the ac-

tive users by designing interaction and affordance that

assist them limiting their interactions with unverified

content.

To describe the Guidance design principle, we

present a design prototype that promotes the target

behavior 1 by simplifying sharing interactions, illus-

trated in Figure 3. The prototype follows the Guid-

ance design principle that increases users’ interac-

tion ability with credible information by reducing the

number of interaction steps required for sharing cred-

ible information. The Share button has the biggest

impact on digital footprints as this functionality al-

lows users to share the information with the users of

their network; the Comments and Like buttons have

smaller digital footprints compared to that. Facebook

includes different sharing options, such as share pub-

licly or privately, and users get those sharing options

when they press the share button. In addition to the af-

fordance presented in Figure 2, this prototype has dif-

ferent sharing options upfront and reduces the num-

ber of interaction steps for sharing. The prototype

includes the privately sharing option to facilitate the

motivated passive users’ interactions toward the cred-

ible information. As passive users have a natural in-

clination to avoid digital footprint, the motivated pas-

sive users will feel comfortable sharing credible in-

formation privately to their friends rather than sharing

publicly with the whole network. The prototype also

includes additional 2 sharing options that enable users

to share the verified fact-checked information with a

single step of interaction. The design can apply visual

cues on those buttons or use text to guide users about

the interactions that lead to the distribution of credible

information on the social platform.

CHIRA 2021 - 5th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

162

Figure 3: Prototype describing the Guidance design princi-

ple for promoting target behavior 1.

4.3 Incentive on Making the Truth

Louder

The purpose of Incentive design principle is to en-

courage and motivate users to orient their interaction

behavior in a direction that can make the truth louder

on the platform. The Incentive design principle is a

Spark prompt in the FBM that is proven effective for

the individuals who have the high ability but low mo-

tivation to perform the target behaviors. This design

principle can prompt the less motivated active users

to perform target behavior 1 and the less motivated

passive users to perform target behavior 2.

To describe the Incentive design principle, we

present a design prototype that promotes the target be-

havior 1 by providing users badges, illustrated in Fig-

ure. 4. The concept of ‘Community Service Badges’

can demonstrate a way to incentivize social media

users to increase their motivation for performing the

target behaviors. When users perform social media

interactions for making the truth louder, they will re-

ceive badges. The platform can add benefits to the

badges, such as prioritizing the content posted by

users who have the badges, suggesting other users

to follow the individuals who hold the badges due to

the contribution in distributing credible information.

Such platform-based benefits can attract active users

to become reflective about their social media interac-

tions and perform interactions only with credible in-

formation.

The platform-affordances can communicate with

users and encourage them to participate in making the

truth louder as a part of their responsibilities for cre-

ating personal, social, and societal impacts. Figure

4 includes the text “Please participate in distribut-

ing credible information; your friends may benefit”

to communicate with social media users and inspire

their motivation. As the community service badges

indicate individuals’ effort to make the truth louder

on social platforms, the badges can gather positive

impressions from other social media users, which can

attract the platform’s active users to attain the badges.

The platform-based interventions can identify useful

information and harmful information by relying on

the fact-checking services and assist users in devel-

oping the interaction habits by rewarding them with

the badges.

Figure 4: Prototype describing the Incentive design princi-

ple for promoting target behavior 1.

In summary, we present 3 design principles to

make the truth louder that are adaptive to users’ in-

teraction tendencies. The relationships between the

design principles and the credibility of the post, the

target behaviors, and the user’s interaction tendencies

is shown in Table 1. These design principles encour-

age UX researchers to design and create affordances

on the social media posts that are adaptive to individ-

uals’ interaction tendencies.

5 FUTURE WORK

We are developing alternative design instances that

follow these design principles as a basis for evalu-

ating the effectiveness of those instances on users’

achieving the target behaviors considering their ac-

tive passive tendencies. In our evaluation studies, we

plan to collect information about participants’ social

media usage and identify their interaction tendencies

with a self report survey. We will ask participants to

report their level of motivation to adopt the 2 target

behaviors and compare their self-reported responses

with the observations data that we collect in the study.

In the study, participants will see social media posts

containing both credible and questionable informa-

tion and will be divided into experiment conditions so

that we can compare the results between controlled

and treatment conditions. The findings of the study

can be the basis for developing an AI model that

presents effective intervention designs in response to

users’ interaction tendencies to optimize making the

truth louder.

Reframing the Fake News Problem: Social Media Interaction Design to Make the Truth Louder

163

Table 1: The design principles can measure the effectiveness of intervention designs for making the truth louder.

Factual status

of the post

that appears on

user’s social

media feed

Target behavior

to promote

User’s

interaction

tendencies on

the platform

User’s motivation

to contribute in

making the truth

louder

Appropriate design principle

to apply on the post

to promote the target behavior

for the user

When information

of the post

is credible

Target behavior 1

High Low

Incentive principle for active user

High High

Awareness principle for active user

Low High

Guidance principle for passive user

When information

of the post

is questionable

Target behavior 2

Low Low

Incentive principle for passive user

Low High

Awareness principle for passive user

High High

Guidance principle for active user

6 CONCLUSION

This paper provides a theoretical basis for structur-

ing the design space around misinformation interven-

tions, which addresses users’ active-passive tenden-

cies as behavior, develops design principles to trans-

form the interaction behavior, and identifies 2 interac-

tion behaviors to promote to make the truth louder on

social media. We develop 3 design principles of social

media interactions and present associated prototypes

to explain the design principles - those principles can

be used to evaluate the effectiveness of design in-

stances for combating misinformation. We interpret

the problematic issue of misinformation spreading on

social platforms as a design challenge for UX re-

searchers to create platform-based affordances that

encourage users to adopt new interaction behaviors:

interact more with credible content and interact less

with harmful content. Instead of solely relying on re-

ducing the spread of misinformation, we encourage

UX researchers to explore design ideas of the 3 de-

sign principles and address the difference between ac-

tive and passive users to create affordances that nudge

users’ interactions to distribute credible information.

REFERENCES

Acquisti, A., Adjerid, I., Balebako, R., Brandimarte, L.,

Cranor, L. F., Komanduri, S., Leon, P. G., Sadeh, N.,

Schaub, F., Sleeper, M., et al. (2017). Nudges for pri-

vacy and security: Understanding and assisting users’

choices online. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR),

50(3):1–41.

Arif, A., Shanahan, K., Chou, F.-J., Dosouto, Y., Starbird,

K., and Spiro, E. S. (2016). How information snow-

balls: Exploring the role of exposure in online rumor

propagation. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Con-

ference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work &

Social Computing, pages 466–477. ACM.

Babu, A., Liu, A., and Zhang, J. (2017). New up-

dates to reduce clickbait headlines. (may 2017).

https://about.fb.com/news/2017/05/news-feed-fyi-

new-updates-to-reduce-clickbait-headlines/.

Bentley, F., Quehl, K., Wirfs-Brock, J., and Bica, M. (2019).

Understanding online news behaviors. In Proceed-

ings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors

in Computing Systems, pages 1–11.

Bhuiyan, M. M., Zhang, K., Vick, K., Horning, M. A., and

Mitra, T. (2018). Feedreflect: A tool for nudging users

to assess news credibility on twitter. In Companion

of the 2018 ACM Conference on Computer Supported

Cooperative Work and Social Computing, pages 205–

208.

Chen, A., Lu, Y., Chau, P. Y., and Gupta, S. (2014). Classi-

fying, measuring, and predicting users’ overall active

behavior on social networking sites. Journal of Man-

agement Information Systems, 31(3):213–253.

Coleman, K. (2021). Introducing birdwatch, a community-

based approach to misinformation (january 2021).

https://blog.twitter.com/en\ us/topics/product/

2021/introducing-birdwatch-a-community-based-

approach-to-misinformation.html.

Crowell, C. (2017). Our approach to bots and misin-

formation. (june 2017). https://blog.twitter.com/

en\ us/topics/company/2017/Our-Approach-Bots-

Misinformation.html.

Flintham, M., Karner, C., Bachour, K., Creswick, H.,

Gupta, N., and Moran, S. (2018). Falling for fake

news: investigating the consumption of news via so-

cial media. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

1–10.

Fogg, B. J. (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design.

In Proceedings of the 4th international Conference on

Persuasive Technology, pages 1–7.

Geeng, C., Yee, S., and Roesner, F. (2020). Fake news

on facebook and twitter: Investigating how people

(don’t) investigate. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI

conference on human factors in computing systems,

pages 1–14.

Gerson, J., Plagnol, A. C., and Corr, P. J. (2017). Passive

and active facebook use measure (paum): Validation

and relationship to the reinforcement sensitivity the-

ory. Personality and Individual Differences, 117:81–

90.

Gleicher, N. (2019). Removing coordinated inauthentic be-

CHIRA 2021 - 5th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

164

havior from china. (august 2019). https://about.fb.

com/news/2019/08/removing-cib-china/.

Grace, L. and Hone, B. (2019). Factitious: Large scale com-

puter game to fight fake news and improve news liter-

acy. In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

1–8.

Hughes, T., Smith, J., and Leavitt, A. (2018). Helping peo-

ple better assess the stories they see in news feed with

the context button. (2018). https://about.fb.com/news/

2018/04/news-feed-fyi-more-context/.

Khan, M. L. (2017). Social media engagement: What moti-

vates user participation and consumption on youtube?

Computers in Human Behavior, 66(4):236–247.

Kumar, S. and Shah, N. (2018). False information on

web and social media: A survey. arXiv preprint

arXiv:1804.08559.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., and Cook, J. (2017). Be-

yond misinformation: Understanding and coping with

the “post-truth” era. Journal of applied research in

memory and cognition, 6(4):353–369.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz,

N., and Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its

correction: Continued influence and successful debi-

asing. Psychological science in the public interest,

13(3):106–131.

Marwick, A. E. (2018). Why do people share fake news?

a sociotechnical model of media effects. Georgetown

Law Technology Review, 2(2):474–512.

Mele, N., Lazer, D., Baum, M., Grinberg, N., Friedland,

L., Joseph, K., Hobbs, W., and Mattsson, C. (2017).

Combating fake news: An agenda for research and ac-

tion. Retrieved on October, 17:2018.

Morris, M. R., Counts, S., Roseway, A., Hoff, A., and

Schwarz, J. (2012). Tweeting is believing? under-

standing microblog credibility perceptions. In Pro-

ceedings of the ACM 2012 conference on computer

supported cooperative work, pages 441–450.

Nekmat, E. (2020). Nudge effect of fact-check alerts:

Source influence and media skepticism on sharing of

news misinformation in social media. Social Media+

Society, 6(1):2056305119897322.

Nonnecke, B. and Preece, J. (1999). Shedding light on lurk-

ers in online communities. Ethnographic Studies in

Real and Virtual Environments: Inhabited Informa-

tion Spaces and Connected Communities, Edinburgh,

123128.

Pennycook, G., McPhetres, J., Zhang, Y., Lu, J. G., and

Rand, D. G. (2020). Fighting covid-19 misinforma-

tion on social media: Experimental evidence for a

scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychological

science, 31(7):770–780.

Perez, E. B., King, J., Watanabe, Y. H., and Chen, X.

(2020). Counterweight: Diversifying news consump-

tion. In Adjunct Publication of the 33rd Annual ACM

Symposium on User Interface Software and Technol-

ogy, pages 132–134.

Preece, J. and Shneiderman, B. (2009). The reader-to-leader

framework: Motivating technology-mediated social

participation. AIS transactions on human-computer

interaction, 1(1):13–32.

Roozenbeek, J. and van der Linden, S. (2019). Fake news

game confers psychological resistance against online

misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(1):1–

10.

Rosen, G. (2021). How we’re tackling misin-

formation across our apps (2021). https:

//about.fb.com/news/2021/03/how-were-tackling-

misinformation-across-our-apps/.

Rosen, G. and Lyons, T. (2019). Remove, reduce, inform:

New steps to manage problematic content. (april

2019). https://about.fb.com/news/2019/04/remove-

reduce-inform-new-steps/.

Roth, Y. and Harvey, D. (2018). How twitter is fight-

ing spam and malicious automation. (june 2018).

https://blog.twitter.com/en\ us/topics/company/

2018/how-twitter-is-fighting-spam-and-malicious-

automation.html.

Roth, Y. and Pickles, N. (2020). Updating our approach to

misleading information. https://blog.twitter.com/en\

us/topics/product/2020/updating-our-approach-to-

misleading-information.html.

Shao, G. (2009). Understanding the appeal of user-

generated media: a uses and gratification perspective.

Internet research, 19(1):7–25.

Smith, J. (2017). Designing against misinformation. (de-

cember 2017). https://medium.com/facebook-design/

designing-against-misinformation-e5846b3aa1e2.

Starbird, K. (2017). Examining the alternative media

ecosystem through the production of alternative nar-

ratives of mass shooting events on twitter. In Eleventh

International AAAI Conference on Web and Social

Media.

Starbird, K., Arif, A., Wilson, T., Van Koevering, K., Yefi-

mova, K., and Scarnecchia, D. (2018). Ecosystem or

echo-system? exploring content sharing across alter-

native media domains. In Proceedings of the Inter-

national AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media,

volume 12.

Su, S. (2017). New test with related articles (2017).

https://about.fb.com/news/2017/04/news-feed-fyi-

new-test-with-related-articles/.

Thaler, R. H. and Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving

decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Pen-

guin.

Torres, R., Gerhart, N., and Negahban, A. (2018). Combat-

ing fake news: An investigation of information veri-

fication behaviors on social networking sites. In Pro-

ceedings of the 51st Hawaii international conference

on system sciences.

Trifiro, B. M. and Gerson, J. (2019). Social media usage

patterns: Research note regarding the lack of universal

validated measures for active and passive use. Social

Media+ Society, 5(2):2056305119848743.

Reframing the Fake News Problem: Social Media Interaction Design to Make the Truth Louder

165