Preventing Sexual Violence against Children: Parents' Perception in

Pontianak City

Izkah Shafha Ramdinar, Linda Suwarni

a

, Selviana, Vidyastuti, Widya Lestari

Health Science Faculty, Universitas Muhammadiyah Pontianak, Jenderal Ahmad Yani Street, Pontianak, Indonesia

widya.lestari@unmuhpnk.ac.id

Keywords: Sexual Violence, Children, Parents’ Perception

Abstract: Cases of violence against children tend to increase from year to year. One of the protective factors for children

against sexual violence is parenting. Perceptions of sexual violence against children are essential, which

impact prevention programs for violence against children. This study explored parents' perceptions of sexual

violence against children as well as prevention practices. This study was a qualitative design, using an in-

depth interview with parents who have children under 18th years old. Maximum variation sampling was used.

Ten participants contribute to this study. The majority of participants in this study defined sexual violence

against children as limited to sexual acts that lead to forced sexual relations. The challenges faced by the

participants were taboo, lack of correct knowledge in sexuality education in children, limited skills in

communicating sexuality to children, and lack of self-confidence. There are disparities in understanding the

meaning of sexual violence against children, and challenges in prevention need to be discussed further.

1 INTRODUCTION

Children are an investment in the future of a nation,

but there are still many problems that arise, one of

which is violence. Violence against children has

received international recognition as a violation of

social and human rights. Common causes and

supporting factors for violence against children are

related to society's traditions, customs, and culture

(Levinson, 1989). Child sexual violence is a form of

violence against children that is rife recently. Sexual

violence and sexual harassment are two different

things. Sexual violence is a term that has a broader

scope than sexual harassment. Sexual harassment is

one type of sexual violence (World Health

Organization, 2013).

Cases of violence against children tend to increase

from year to year. Based on the 2017 Global Report,

73.7% of Indonesian children aged 1-14 years

experience physical and psychological violence at

home as an effort to discipline (Global Report, 2017).

The number of violence against children recorded

from January to June 2020 was 3,928 cases,

consisting of sexual, physical, and emotional violence

cases, and nearly 55% of them experienced sexual

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0862-4881

violence (Medistiara, 2020). It was exacerbated by

the Covid-19 pandemic, which impacted various

aspects, including an increase in child abuse cases

during the pandemic. The Ministry of Women's

Empowerment and Child Protection noted a

significant increase in cases during the pandemic,

including 852 physical violence, 768 psychological

violence, and 1,848 sexual violence. Recorded

instances of violence against children show that

previously before the pandemic period, there were

1,524 children, increasing to 2,367 children victims

of violence during the Covid-19 pandemic (Kemen

PPPA, 2020).

Child sexual violence is a severe problem that is

difficult to detect (Louwers et al., 2010) (Murray et

al., 2014). Sexual violence against children is any

sexual activity that involves a child (less than 18 years

old) getting sexual satisfaction from sexual comments

or seduction to forced sexual relations (Berlo &

Ploem, 2018). Sexual violence in children has a

prolonged impact on their life cycle (Bellis et al.,

2011).

A protective factor for sexual violence in children

is parenting (Meinck et al., 2015) (Rudolph et al.,

2018) (Scoglio et al., 2019) (Ligiero et al., 2019)

182

Ramdinar, I., Suwarni, L., Selviana, ., Vidyastuti, . and Lestari, W.

Preventing Sexual Violence against Children: Parents’ Perception in Pontianak City.

DOI: 10.5220/0010758900003235

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Determinants of Health (ICSDH 2021), pages 182-188

ISBN: 978-989-758-542-5

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

(McKillop et al., 2019) (McKillop et al., 2019) al.,

2021). Parenting patterns in preventing sexual

violence against children require a correct

understanding of sexual violence. This understanding

is essential in determining parents' actions in

providing parenting to children (Collins, 1996).

To our knowledge, in Indonesia, especially the

city of Pontianak, there has been no research that

examines the perceptions of parents who have

children (<18 years) about sexual violence against

children. Although this perception is very decisive in

determining parenting as a protective factor for

children from sexual violence, the law in Indonesia

on sexual violence is still ambiguous and limited to

rape cases only. The impact on the prevention of

sexual violence against children is not

comprehensive. The purpose of this study was to

explore parents' perceptions of sexual violence

against children.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

Maximum variation sampling was used with a set of

criteria for recruiting participants: participants must

be parents of school children as these parents may

begin to consider risks outside the home when their

children are at this age; participants must represent

different backgrounds in terms of work, education,

and economic status; and willing to discuss sexual

violence against children. Ten participants from

diverse demographic backgrounds were recruited to

participate in this study. Participants consisted of two

men (fathers) and eight women (mothers) aged 30-

47

th

. Their sociodemographic characteristics are

shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Participants were recruited between April and

May 2021. Individual interviews were terminated

when it was challenging to find additional insights

from the new data gathered. Before starting data

collection, participants were informed about their

rights as research subjects. They were made aware

that their participation was voluntary and the

information they provided would be kept

confidential. Each interview lasted about 45–60

minutes.

This study has received ethical clearance no:

448/KEPK-FKM/UNIMUS/2021, University of

Muhammadiyah Semarang.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted based

on interview guidelines. Four critical questions about

parents' perceptions of sexual violence against

children include: What is the definition and type or

form of sexual violence against children according to

parents? How do parents understand the risks of

sexual violence against children? What do parents

think about efforts to prevent sexual violence against

children? Two critical questions about parental

practices regarding sexual violence against children

include: What will parents avoid sexual violence

against children? What are parents doing to protect

their children from sexual violence against children?

All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Data

were analyzed using the thematic analysis method

(Guest et al., 2012), which organizes and categorizes

the data according to each participant's main themes

and responses.

3 RESULT

This study conducted to ten participants with indepth

interview technic. The majority participants is 30-39

years old, female, senior high school and employed

(see Table 1). The detail participants in Table 2.

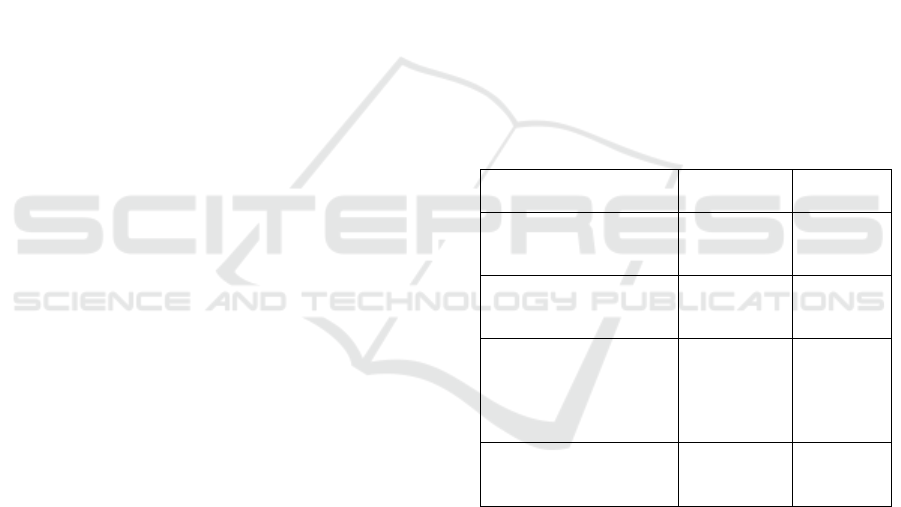

Table 1: Social-demographic characteristics of 10

participants.

Social-demographic

Characteristics

n %

Age

30-39

40-49

6

4

60

40

Sex

Male

Female

2

8

20

80

Level of education

Junior high school

Senior high school

Bachelor degree

Master degree

1

7

1

1

10

70

10

10

Occupation

Employed

Unemploye

d

7

3

70

30

Preventing Sexual Violence against Children: Parents’ Perception in Pontianak City

183

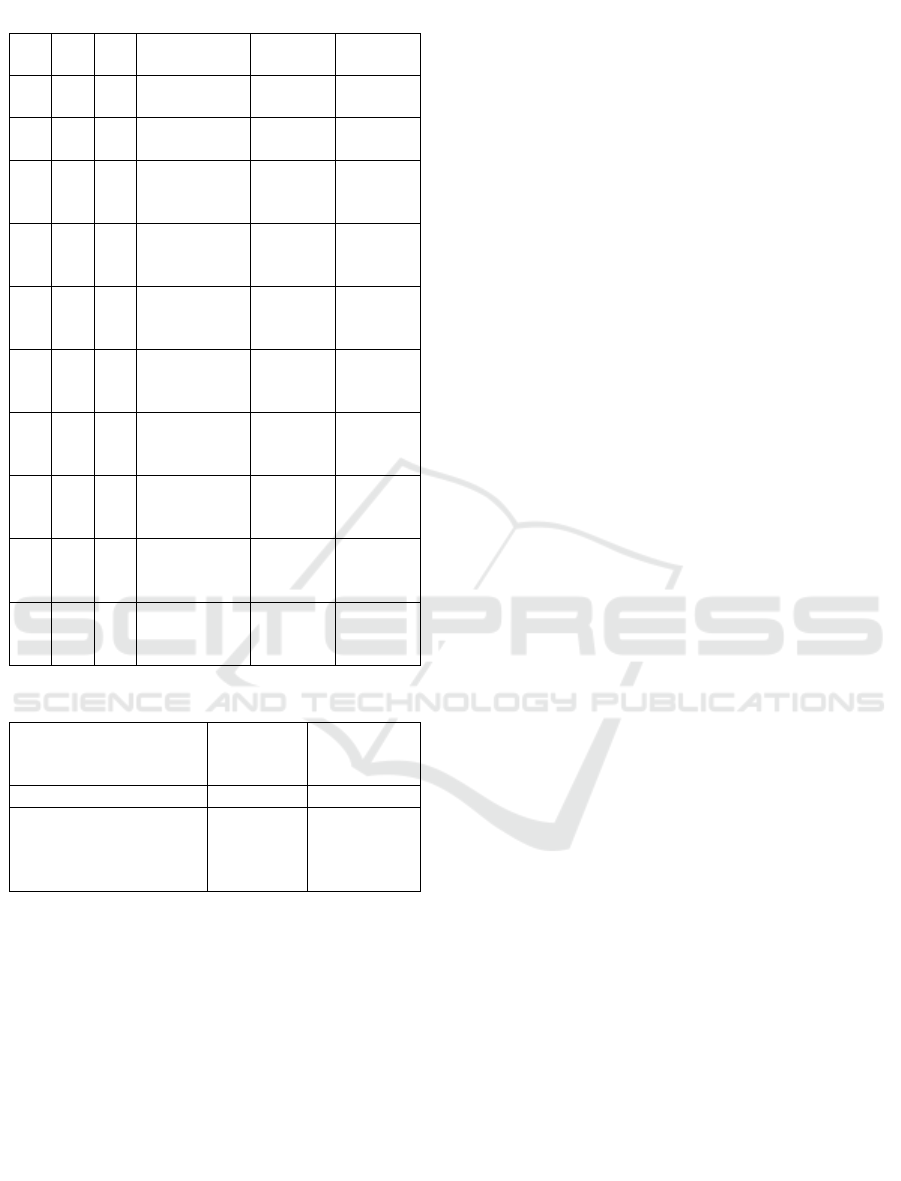

Table 2: Characteristics of participants.

No Sex Age Occupation Education

C

hildren’s

sex/age

M1 M 38

th

Employed Master

de

g

ree

F/8

th

&

M/6

th

M2 M 38

th

Employed Bachelor

degree

F/10

th

&

F/7

th

F1 F 38

th

Employed Senior

high

school

F/11

th

&

M/12

th

F2 F 40

th

Unemployed Junior

high

school

F/12

th

F3 F 47

th

Unemployed Senior

high

school

F/15

th

F4 F 42

th

Unemployed Senior

high

school

F/13

th

F5 F 45

th

Unemployed Senior

high

school

F/16

th

F6 F 39

th

Unemployed Senior

high

school

F/14

th

F7 F 38

th

Unemployed Senior

high

school

F/13

th

&

M/10

th

F8 F 36

th

Unemployed Senior

high

school

F/14

th

&

M/9

th

Table 3: Definition of sexual violence against children

Definition of Sexual

Violence Against

Children

Number

reporting

Percentage*

Ra

p

e 10 100

Other sexual activities

(like kissing, petting,

sensitive areas forcibly

and or violence

3 30

Although all participants specifically defined

physical, sexual activity with a child by force, they

had different standards for the form of sexual activity

performed. The participants' responses can be

grouped into two groups regarding sexual violence

against children, namely rape and other sexual

activities, such as kissing, hugging, touching

sensitive areas forcibly, and violence (see Table 3).

All participants stated that the very narrow limit for

determining sexual violence against children

occurred to forced sexual relations with children

(rape). Only 3 out of 10 participants noted that sexual

violence against children could occur not only

through rape (sexual intercourse) but also in the form

of other sexual activities. As the informant said

below:

"…. Like that… like rape by adults to children…"

(M1)

"…. Playing hands… and forcing sexual

intercourse…." (F1)

"…. That… like holding onto a child's genitals…

kissing… until later on to a husband and wife

relationship…" (M2)

When in-depth interviews were conducted, all

participants reacted embarrassed when asked about

the definition of sexual violence against children.

They felt taboo to talk about sex. As the informant

stated below:

"…. Is that… that… yeah like that… (accompanied

by a shy smile)" (F2)

"… .Hmmm… hmmm…. Yes ... how about it ... it's

hard to talk about it (accompanied by scratching his

head and blushing) (M1)

3.1 Scope and Forms of Sexual

Violence against Children

The in-depth interviews showed that all participants

stated that the scope of sexual violence against

children was rape or sexual immorality. Only four out

of ten participants said that abuse is also included in

sexual violence against children, apart from rape.

Harassment can take the form of kissing, hugging,

holding a child's sensitive area forcibly. As the

informant stated below:

"... the shape and scope are like rape ..." (F8)

"…. Which includes such as a child being kissed, or

being held by a sensitive organ which is done forcibly

... "(F1)

3.2 Causes of Sexual Violence against

Children

This study found that some participants stated that the

cause of sexual violence against children was

promiscuity. Some other participants indicated that

they were influenced by friends and did not listen to

their parents' advice. As the following statement:

"... the cause is due to promiscuity ..." (F4)

"... children like not listening to parents' advice ..."

(F2)

"... the influence of friends too ..." (F6)

In terms of the perpetrator, the cause of sexual

violence against children is the uncontrolled lust of

the perpetrator. As the participants stated below:

"... Cannot control lust ... lust ...." (M2, and F2)

Another informant stated that another cause was

that the wife could no longer serve her husband's lust,

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

184

so she did it to underage children. Several participants

also noted that the current openness of social media is

also the cause of sexual violence against children. The

following is the participants' statement:

"…. Usually it is triggered because the wife cannot be

invited to have sex or often refuses ... "(F7)

"... currently the influence of social media can also be

a cause ..." (F5)

3.3 Victims of Sexual Violence against

Children

According to eight participants, this study stated that

victims of sexual violence against children mainly

occurred in girls (both biological and stepchildren)

and granddaughters. Only two participants said that

apart from girls, it can also happen to boys. The

following is the informant's statement:

"…… The victims are mostly girls… biological or

stepchildren…. Many granddaughters are also

victims…" (M2)

"... indeed there are many victims of the female sex,

but nowadays there are more and more boys who have

become victims ..." (F2)

3.4 Perpetrators of Sexual Violence

against Children

The in-depth interviews showed that all participants

stated that the perpetrators of sexual violence against

children were more family and neighbors (known

people). In addition, outsiders (unknown) are also

perpetrators of sexual violence against children now.

As the informant stated below:

"…. Most cases .. the perpetrators are family such as

an uncle, grandfather, etc., and there are also

neighbors…. People who are known or who are

around the child ... "(M1)

"... if you look at the current trend of cases there are

also many people who are not known ... outsiders ..."

(F8)

3.5 Efforts to Prevent Sexual Violence

against Children

Several participants stated that the attempt to prevent

sexual violence against children strengthened religion

by praying a lot. Several other participants said that

through education on sexual violence against children

from an early age, giving advice, choosing good

friends to hang out with, and limiting gadgets to

children. As the informant stated below:

"Strengthen religion and a lot of worship to prevent

cases of sexual violence against children" (F1)

"…children should be given an education from an

early age… tell private body parts, shout if someone

holds them" (M1)

"Restricting children from playing gadgets" (M2)

"Choose good associates" (F8)

All participants stated that mothers are

responsible for delivering education on the

prevention of sexual violence against them.

"The mother closest to the child" (M1)

"Already nature of mother" (F6)

This study also shows that all participants state

that schools are also responsible for educating

children to prevent sexual violence against children

through the sexual education curriculum. However,

several participants said that even though it was

included in the curriculum, the language used was not

directly related to sexual education. The following is

the informant's statement:

"Schools are also responsible for educating their

students" (M2)

"Agree if the school includes the curriculum" (F1)

"If you can, the name should not be immediately

vulgar in sexual education" (M1)

3.6 Challenges in Education on

Prevention of Sexual Violence

against Children

All participants stated that the biggest challenge in

preventing sexual violence against children is still

taboo and minimal knowledge about what things need

to be conveyed to children to prevent sexual violence.

The participants also stated that when they were little,

their parents never told them either. In addition, some

participants noted that it was difficult to educate

children because of the limited skills and beliefs in

delivering sexual education to prevent sexual

violence against children. As the informant stated

below:

"Awkward, taboo ... parents never taught it, and it was

a taboo" (F1)

"It's hard to be confident and confused about what to

say" (F2)

In addition, several participants stated that the

ongoing Covid-19 pandemic caused the use of

cellphones and internet access to be a challenge in

itself. It is because content that contains pornographic

elements appears on cellphones and when accessing

the internet.

Preventing Sexual Violence against Children: Parents’ Perception in Pontianak City

185

4 DISCUSSION

The majority of participants in this study defined

sexual violence against children as limited to sexual

acts that lead to forced sexual relations. The

participants' responses can be grouped into two

groups regarding sexual violence against children,

namely rape and other sexual activities, such as

kissing, hugging, forcibly touching sensitive areas,

and violence. All participants assumed that mothers

were responsible for delivering education on the

prevention of sexual violence against children. The

challenges faced by the participants were taboo, lack

of correct knowledge in sexuality education in

children, limited skills in communicating sexuality to

children, and lack of self-confidence.

The participants' limited understanding of sexual

violence against children is only in the form of sexual

acts that lead to forced sexual intercourse, affecting

providing sexual prevention education to children

because there is a process before sexual intercourse.

Limitations regarding the notion of sexual violence

have also been reported in several previous studies

(Mathoma et al., 2006) (Ige & Fawole, 2011)

(Jayapalan et al., 2018) (Baldwin-White, 2021). This

misunderstanding also occurred with police officers

who handled cases of sexual violence against children

(Ricciardelli et al., 2021) and the doctors who dealt

with the patients (Andrea & Roland, 2017) (Adams,

2020). WHO defines sexual violence against children

as all sexual acts to get sexual satisfaction, both verbal

(erotic/sexual comments/seductions) or physical

(kissing, hugging, penetration, etc.) that lead to

sexuality (World Health Organization, 2013). Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) provides a specific

definition, namely sexual acts as forced penetration

with intentional touch, or without penetration, and

sexual harassment without contact, such as exposing a

child to sexual activity, taking sexual photos or videos

of a child, prostitution or child trafficking (Leeb et al.,

2008). This understanding is fundamental in leading

to better programs and strategies for preventing sexual

violence against children (Sarno & Wurtele, 1997)

(World Health Organization, 2012) (Murray et al.,

2014) (Rudolph et al., 2018). Education from families

is crucial for preventing cases of sexual violence

(Hackman et al., 2017).

The majority of participants stated that most of the

perpetrators of sexual violence against children were

family members. Contrast with previous research,

which says that most sexual violence against children,

including sexual abuse, is a recurring chronic event

caused by family members (Andrea & Roland, 2017)

even though the family should protect children from

crimes, including sexual violence (Rahimi, 2020)

(Rudolph et al., 2018). Adults, including parents, act

as supervisors to create a safe (conducive)

environment for children to prevent crime, including

sexual crimes against children (Leclerc et al., 2015;

Leclerc et al., 2011). Lastly, parents as gatekeepers of

children have an essential impact on the risk of sexual

violence, including sexual harassment (Meschke &

Peter, 2014) (Mendelson & Letourneau, 2015)

(Fideyah et al., 2020).

All participants in this study stated that the mother

is the most responsible person in delivering education

about sexuality to children. Several studies have

shown that mothers psychologically have a close

relationship with their children so that sexuality

communication is more effective (Muhwezi et al.,

2015) (Nurachmah et al., 2018) (Faudzi et al., 2020).

Supported by other studies that children are more

open with mothers than fathers, making it easier to

establish communication and discussion about

sexuality (Wang et al., 2016) (Shams et al., 2017).

However, sexuality education in children is a shared

responsibility between the mother and father

(Nasution et al., 2019).

The myths circulating about sexual violence are

still problems and challenges to be faced (Zatkin et al.,

2021). The in-depth interviews' findings were related

to the difficulties faced to prevent sexual violence

against children. All participants stated that they still

felt awkward (taboo) in conveying sexuality to

prevent sexual violence against children. Supported

by previous research also shows that there are still

many parents who are taboo in delivering sexual

education (Grusec, 2011) (Manivasakan & Sankaran,

2014) (Suwarni et al., 2015) (Amaliyah & Nuqul,

2017) (Shams et al., 2017). Limited knowledge about

sexuality, inadequate skills in sexuality

communication (Shams et al., 2017). Other qualitative

study findings revealed that cultural resistance more

effectively limits the nature and content of sexual

health education than religious prohibition

(Onwuezobe & Ekanem, 2009). Parents feel they have

limited knowledge about the content of sexuality and

do not have the skills and self-confidence to discuss

sexual topics (social taboos). This social taboo that can

hinder sexual education has also been found in other

studies in Asia, Africa, and other countries in the

Western Pacific (UNESCO, 2015).

Participants (parents) agreed that sexual education

was school-based by integrating school curricula and

religious lessons. Religious education is essential in

preventing sexual violence against children (Ganji et

al., 2017) (Moghadam & Ganji, 2019). This study

also shows that parents' self-confidence and skills are

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

186

still low in delivering sexuality education to prevent

sexual violence against children. One of the factors

causing the lack of self-confidence and skills in

providing sexuality education is the limited

knowledge of parents about the material. Previous

research supports parents who still have minimal

knowledge and understanding of sexual and

reproductive health (Shams et al., 2017) (Ram et al.,

2020).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Our findings indicate that parents' perceptions of

sexual violence against children are still narrow and

limited. Challenges in preventing sexual violence in

the family environment include taboo in talking about

sexuality, lack of correct knowledge in sexuality

education for children, little skills in communicating

sexuality to children, and self-confidence. The

recommendations of this study are based on the

findings that have been stated, namely that a

comprehensive intervention is needed for parents so

that they can provide proper education to prevent

sexual violence against children. Apart from

knowledge interventions, interventions are also

required to increase the self-confidence and skills of

parents in delivering sexual education to their

children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the Ministry of Research and

Technology of the Republic of Indonesia for funding

this research in the applied research grant in 2021.

Thank you also to all the participants in this research.

REFERENCES

Berlo, W. V. & Ploem, R.. (2018). Sexual violence. The

Netherlands: Rutgers.

Faudzi, N. M., Sumari, M. & Nor, A. M.. (2020). Mother-

Child Relationship and Education on Sexuality. .

International Journal of Academic Research in

Business and Social Sciences, 10(3), pp. 787-796.

Leeb, R. T., Paulozzi, L., Melanson, C. & et al. (2008).

Child maltreatment surveillance: uniform definitions

for public health and recommended data elements,

version 1.0., Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention

and Control.

Onwuezobe, I. A. & Ekanem, E. E. (2009). The attitude of

teachers to sexuality education in a populous local

government area in Lagos, Nigeria. Pak J Med Sci,

25(6), pp. 934-937.

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional

estimates of violence against women: prevalence and

health effects of intimate partner violence and non-

partner sexual violence, s.l.: World Health

Organization.

Adams, J. A. (2020). Sexual abuse in children: What the

general practice ob/gyn needs to know. Clinical

Obstetrics and Gynecology, 63(3), pp. 486-490.

Amaliyah, S. & Nuqul, F. L. (2017). Exploration of

Mother's Perceptions of Sex Education for Children.

Psympathic, 4(2), pp. 157-166.

Andrea, E. & Roland, C. (2017). Female child sexual abuse.

Orvosi Hetilap, 158(23), pp. 910-917.

Baldwin-White, A., (2021). College Students and Their

Knowledge and Perceptions About Sexual Assault.

Sexuality and Culture, 25(1), pp. 58-74.

Bellis, M. D., Spratt, E. G. & Hooper, S. R. (2011).

Neurodevelopmental Biology Associated Childhood

Sexual Abuse. J Child Sex Abus, 20(5), pp. 548-587.

Collins, M. E., 1996. ‘Parents’ Perceptions of the Risk of

Child Sexual Abuse and their Protective Behaviors:

Findings from a Qualitative Study. Child Maltreatment,

1(1), pp. 53-56.

Fideyah, N. A., Muda, S. M., Zain, N. M. & Hamid, S. H.

(2020). The role of parents in providing sexuality

education to their children. Makara J Health Res, 24(3),

p. 157−163.

Ganji, J. et al. (2017). The existing approaches to sexuality

education targeting children: A review article. Iran J

Public Health, Volume 46, pp. 890-898.

Global Report. (2017). Ending Violence in Childhood, s.l.:

s.n.

Grusec, J. E. (2011). Socialization processes in the family:

social and emotional development. Annu Rev Psycho,

Volume 62, pp. 243-269.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M. & Namey, E. E. (2012).

Appliedthematic analysis. s.l.:Thousand Oaks, CA:

SAGE Publications, Inc.

Hackman, C. L. et al. (2017). Slut-shaming and victim-

blaming: a qualitative investigation of undergraduate

students’ perceptions of sexual violence. Sex Education,

17(6).

Ige, O. K. & Fawole, O. I. (2011). Preventing child sexual

abuse: parents' perceptions and practices in urban

Nigeria. J Child Sex Abus, 20(6), pp. 695-707.

Jayapalan, A., Wong, L. P. & Aghamohammadi, N. (2018).

A qualitative study to explore understanding and

perception of sexual abuseamong undergraduate

students of different ethnicities. Women's Studies

International Forum, Volume 69, pp. 26-32.

Kemen PPPA. (2020). 3000 Cases of Child Violence during

the Covid-19 Pandemic, s.l.: s.n.

Leclerc, B., Smallbone, S. & Wortley, R. (2015).

Prevention nearby: The influence of the presence of a

potential guardian on the severity of child sexual abuse.

Preventing Sexual Violence against Children: Parents’ Perception in Pontianak City

187

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment,

Volume 27, pp. 189-204.

Leclerc, B., Wortley, R. & Smallbone, S. (2011). Getting

into the script of adult child sex offenders and mapping

out situational prevention measure. Journal of Research

in Crime and Delinquency, Volume 48, pp. 209-237.

Levinson, D. (1989). Violence in cross-cultural

perspective. Newbury Park, California: Sage.

Ligiero, D. et al. (2019). What works to prevent sexual

violence against children: evidence review, s.l.:

Executive Summary. Together for Girls.

www.togetherforgirls.org/svsolutions.

Louwers, E. C. et al. (2010). Screening for child abuse at

emergency departments: a systematic review. Arch Dis

Child, 95(3), pp. 214-8.

Manivasakan, J. & Sankaran, S. (2014). Sexual health

education- is it still a taboo? A survey from an urban

school in Puducherry. International Journal of

Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and

Gynecology, 3(1), pp. 158-161.

Mathoma, A. M. et al. (2006). Knowledge and Perceptions

of Parents Regarding Child Sexual Abuse in Botswana

and Swaziland. International Pediatric Column. 21(1).

pp. 67-72.

McKillop, N., Reynald, D. M. & Rayment-McHugh, S.

(2021). (Re)Conceptualizing the role of guardianship in

preventing child sexual abuse in the home. Crime

Prevention and Community Safety. Volume 23. pp. 1-18.

Medistiara, Y. (2020). PPA Minister: From January-June

2020 there were 3,928 cases of child abuse.

https://news.detik.com/berita/d-5103613/menteri-ppa-

dari-januari-juni-2020-ada-3928-kasus-kekerasan-

anak: DetikNews.

Meinck, F., Cluver, L. D., Boyes , M. E. & Mhlongo, E. L.

(2015). Risk and Protective Factors for Physical and

Sexual Abuse of Children and Adolescents in Africa: A

Review and Implications for Practice. Trauma,

Violence, & Abuse, 16(1), pp. 81-107.

Mendelson, T. & Letourneau, E. J. (2015). Parent-focused

prevention of child sexual abuse. Prevention Science,

Volume 16, pp. 844-852.

Meschke, L. L. & Peter, C. R. (2014). Hmong american

parents’ views on promoting adolescent sexual health.

American Journal of Sexuality Education, 9(3), p. 308–

328.

Moghadam, S. H. & Ganji, J. (2019). The role of parents in

nurturing and sexuality education for children from

Islamic and scientific perspective. Journal of Nursing

and Midwifery Sciences, 6(3), pp. 149-155.

Muhwezi, W. W. et al. (2015). Perceptions and experiences

of adolescents, parents and school administrators

regarding adolescent-parent communication on sexual

and reproductive health issues in urban and rural

Uganda. Reproductive Health, pp. 1-16.

Murray, L. K., Nguyen, A. & Cohen, J. A. (2014). Child

Sexual Abuse. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am,

23(2), pp. 321-337.

Nasution, F., Rusman, A. A. & Apriadi, P. (2019). The

parent perception of early sex education in children at

Simatahari Village, The Sub District of Kota Pinang. -

International Journal on Language, Research and

Education Studies, 3(1), pp. 85 - 93.

Nurachmah, E. et al. (2018). Mother-daugther

communication about sexual and reproductive health

issues in Singkawang, West Kalimantan, Indonesia.

Enferia Clinica, 28(1), p. 172–175.

Rahimi, S. (2020). Protecting children from sexual abuse in

the family environment. Child & Adolescent Health,

4(4), p. 263.

Ram, S., Andajani, S. & Mohammadnezhad, M. (2020).

Parent’s Perception regarding the Delivery of Sexual

and Reproductive Health (SRH) Education in

Secondary Schools in Fiji: A Qualitative Study. Journal

of Environmental and Public Health, Volume 2020, pp.

1-8.

Ricciardelli, R., Spencer, D. C. & Dodge, A. (2021).

“Society Wants to See a True Victim”: Police

Interpretations of Victims of Sexual Violence. Feminist

Criminology, 16(2), pp. 216-235.

Rudolph, J., Zimmer-Gembeck, J., Shanley, D. C. &

Hawkins, R. (2018). Child Sexual Abuse Prevention

Opportunities: Parenting, Programs, and the Reduction

of Risk. Child Maltreatment, 23(1), pp. 96-106.

Sarno, J. A. & Wurtele, S. K. (1997). Effects of a Personal

Safety Program on Preschoolers. Child Maltreatment,

2(1), pp. 35-45.

Scoglio, A. J. et al. (2019). Systematic Review of Risk and

Protective Factors for Revictimization After Child

Sexual Abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(1), pp.

41-53.

Shams, M., Parhizkar, S., Mousavizadeh, A. & Majdpour,

M. (2017). Mothers ’ views about sexual health

education for their adolescent daughters : a qualitative

study. Reproductive Health , 14(24), pp. 1-6.

Suwarni, L., Ismail, D., Prabandari, Y. S. & Adiyanti, M.

G. (2015). Perceived parental monitoring on

adolescence premarital sexual behavior in Pontianak

City, Indonesia. Int J Public Health Sci, 4(4), pp. 211-

219.

UNESCO. (2015). ttitudinal Survey Report on the Delivery

of HIV and Sexual Reproductive Health Education in

School Settings in Palau, Paris, France: UNESCO.

Wang, X. L., Xie, Q. W. & Qiao, D. P. (2016). Parent-

Involved Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse: A

Qualitative Exploration of Parents’ Perceptions and

Practices in Beijing. Journal of Child and Family

Studies, Volume 25, p. pages999–1010.

World Health Organization. (2012). Understanding and

addressing violence against women, s.l.: World Health

Organization.

Zatkin, J., Sitney, M. & Kaufman, K. (2021). The

Relationship Between Policy, Media, and Perceptions

of Sexual Offenders Between 2007 and 2017: A Review

of the Literature. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, p. DOI

10.1177/1524838020985568.

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

188