Planetary Health: A Grassroot Experience of Indonesian Sea Nomads

in Solid Waste Management in Bajau Mola Raya, Wakatobi Regency,

Southeast Sulawesi

Wengki Ariando

1a

, Kartika C. Sumolang

2

and Imas Arumsari

3b

1

International Program of Environment Development and Sustainability, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

2

World Wide Fund (WWF) Indonesia, Southern Eastern Sulawesi Sub-seascap Program, Wakatobi, Indonesia

3

Nutrition Department, University of Muhammadiyah Prof DR. Hamka,Jl. Limau II, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Bajau, Local Knowledge, Planetary Health, Sea Nomads, Solid Waste.

Abstract: Indigenous peoples as one of the actors for preserving the environment with their valuable cultural practices

also become spotlight to be incorporated to pursue the planetary health concept. This research contributes to

give evidence in the failure system of implementing planetary health concept at the grassroots level for human

aptitude in the case of the Indonesian Sea Nomads community namely Bajau people in Mola Raya, Wakatobi

Regency. The qualitative setting was implied in this research using ethnography. Preferably, Bajau people

through their knowledge should be recognized as a practice model toward adapting the concept of planetary

health including solid waste management practice. It was found a failure action and stimulus programs from

multi-stakeholders who have been working with Bajau people to date, which also been influenced by the

political situation. Bajau people realize their failures of implementing local knowledge but they were rolled

into the complex system. Bajau people are labeled to be the actor of environmental damages for marine living

resources and as low intention people to ecosystem health. As impacts, Bajau people has a high risk of public

health issues and social blaming regarding their destructive practices.

1 INTRODUCTION

Interdisciplinary issues in the current public health

debate are becoming the spotlight since there has

been a shared commitment to sustainable

development goals (SDGs) (Clifford and Zaman,

2016). Practically, public health quality improvement

programs should imply a situated approach according

to the community needs. This specific approach

undoubtedly must be based on experience and local

wisdom backward to the root of the problem of public

health itself. Local and cultural-based approaches are

currently considered as the most suitable alternative

to today's challenges (Dickerson et al., 2020). In

advance, the environmental issue is one that affects

the interaction between humans and ecosystems as in

the concept of the planetary health approach (Lerner

and Berg, 2017, Horwitz and Parkes, 2019).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7244-8475

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2743-2730

The Lancet Planetary Health Commission

reported calls for the “training of indigenous and

other local community members” in order to “help to

protect health and the biodiversity” (Redvers, 2018).

This concept explains how indigenous peoples play

an important role in protecting the environment

through traditional ecological knowledge (Berkes,

1993) and their own health system (Finn et al., 2017).

Furthermore, this planetary health concept has

developed into an approach which defined as the safe

“planetary playing field”, or the “safe operating space

for humanity” to stay within if we want to make sure

to avoid environmental changes in the major human-

induced on a global scale (Redvers et al., 2020).

Modern and complex ideas regarding social and

environmental issues that apply to the planetary

health have been considered as hereditary knowledge

by indigenous communities since time immemorial.

The success of the future generation lies in caring and

214

Ariando, W., Sumolang, K. and Arumsari, I.

Planetary Health: A Grassroot Experience of Indonesian Sea Nomads in Solid Waste Management in Bajau Mola Raya, Wakatobi Regency, Southeast Sulawesi.

DOI: 10.5220/0010760700003235

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Determinants of Health (ICSDH 2021), pages 214-222

ISBN: 978-989-758-542-5

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

upholding the planet in good health (Behera et al.,

2020), as a main discussion in this research.

The relationship between planetary health and

indigenous peoples as a general concept, certainly has

its own challenges (Capon, 2020), especially in the

implementation and influence of the alignments of

policymakers and public awareness itself. These

kinds of perceptions often become obstacles and gaps

in how global commitment is adopted into local

terms. This nature disconnect grows rapidly, there is

a consideration to be transformative changes inside

and outside public health and healthcare spaces

(Redvers et al., 2020). The basic concept is actually

close to indigenous peoples, both those who live on

land or who live on the coast and marine areas, such

as the Bajau Mola community in Wakatobi Regency,

Southeast Sulawesi Province, Indonesia.

Due to the planetary concept is very broad, this

research overlooked the locus of solid waste

management as the specific analysis guidance. The

socio-economic information of the Bajau Mola

community and Wakatobi Regency also becomes a

considerable background in order to present the

research gap, especially those who have not

succeeded in solving this environmental problem.

The behaviour of the Bajau people themselves as a

community whose ancestors lived in the sea has not

been educated enough to dispose of solid waste in its

place. This has become an issue with the Wakatobi

Regency government lately. The Bajau Mola as the

most densely populated village in Wakatobi with a

total population of 7619 people (Statistic Indonesia,

2021) contributes to waste in the waters of Wakatobi

Regency. This issue is exacerbated by the conflict of

interest in the area between the Bajau, Wakatobi

National Park (WNP) authorities and the coastal

community development program in Wakatobi

Regency. Bajau identity as immigrants has low

collective rights and a local capitalized system

(Wianti et al., 2012). From a socio-economic point of

view, the Bajau people are also vulnerable to

becoming a modern society that will lose their

cultural identity (Marlina et al., 2021). The way of life

Bajau people depends on marine resources for their

food, shelter, livelihoods, and cultural needs.

If it is returned to global issues, this research

implicitly contributes to outlining the facts on the

ground regarding the concepts of planetary health,

Bajau culture, and solid waste management in the

Wakatobi Regency. In more ambitious impacts, the

global environmental change and climate crisis, and

also the existence of pandemics are all consequences

of not following the natural laws that are encapsulated

by the interrelated global nature through planetary

health (Redvers et al., 2020). The natural laws as part

of traditional ecological knowledge have been

growing into a valuable point in the planetary health

system for instance in solid waste management.

Those natural laws that grow in Bajau people should

be a practiced model that must be strengthened in

solid waste management in Wakatobi Regency as

stated in research hypotheses. There are two points of

main focus in this research, the first is to see the

experience of Bajau Mola in implementing planetary

health in daily life, and the second is to study the

factors that influence the successfulness of planetary

health, particularly in the case of solid waste

management.

2 METHOD

This research implied the qualitative setting using

ethnography from October 2020 to May 2021. The

ethnography was used to see the daily activities of

Bajau people in Mola in interpretating the solid waste

management and the use of their local knowledge.

Then, the observation data would be fit into planetary

health as conceptualized by The Lancet (Horton and

Lo, 2015, Myers, 2017, Horton et al., 2014). The

informants consisted of native Bajau people in Mola

and related stakeholders from local government

offices. The data analysis implied the narrative

approaches where the observation notes was analyzed

in every single talks. In more appropriate steps, this

research followed Riessman (1993) which grouping

the ethnography data analysis into; attending, telling,

transcribing, analysing, reading, and validating.

This ethnographic study was conducted by live-in

with the Bajau Mola community. The stages

consisted of basic data investigations, then continued

with the process of finding cases (solid waste

management), collecting facts, and extracting raw

data. Then, it was followed by reading the group

situation involved and its challenges (planetary

health), interpretation, and data analysis.

Furthermore, all data were validated with the Bajau

Mola to deliberate the findings. The validation and

data analysis process were frequent repeated to

reduce data bias and to get the most valid

ethnographic data.

2.1 Study Area

The Wakatobi Regency was nominated as a marine

national park located in Coral Triangle Initiatives that

becoming a home for the highest marine biodiversity

in Indonesia (White et al., 2014). Another interesting

Planetary Health: A Grassroot Experience of Indonesian Sea Nomads in Solid Waste Management in Bajau Mola Raya, Wakatobi Regency,

Southeast Sulawesi

215

point is that the marine national park covers the whole

areas of the Wakatobi Regency as marine protected

area or known as WNP which legally acknowledge

under the Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

With a resident community of around 100,000 people,

the WNP is Indonesia’s third largest and most

populated marine national park with 5,000 hectare

coral reefs, large offshore atoll, seagrass meadows

and mangrove forests (Clifton and Unsworth, 2009).

Nowadays, the WNP become a priority tourism

attraction of Indonesia in 2019 and it will be intended

as “new Bali” in 2021 (Rathgeber, 2018).

Wakatobi Regency is a group of islands located in

Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. The capital city name

is Wangi-Wangi. Officially, this regency was

established by Law No. 29/2003. The name

“Wakatobi” is an acronym that coming from the first

two letters of four largest islands name in the Tukang

Besi archipelago: Wangi-wangi (WA), Kaledupa

(KA), Tomia (TO), and Binangko (BI). Wakatobi

Regency population is 95,737 inhabitants spreading

in four big islands and 43 small islands. This regency

lies south of the equator, stretching latitudinally from

5º12´ to 6º25´ S and 123º20´ to 124º39´ E. The land

area of the Regency extends approximately 823

square kilometers. The water area is estimated at

around 17,554 square kilometers (Statistics

Indonesia, 2019). Approximately eight percent of

ethnic groups in Wakatobi Regency is Bajau

communities (Elliott et al., 2001).

The health-related situation is shown an

improvement in terms of the number of reported

health problems, however, both of infectious and

chronic diseases still become the major diseases in

Wakatobi Regency. Prevalence of people having

health problems in Wakatobi Regency decreased

from 12.2% in 2018 to 9.4% in 2020 (Badan Pusat

Statistik Kabupaten Wakatobi, 2021). The health

problems represented in this data including acute

diseases, chronic diseases, and traffic road accident.

The morbidity rate of Wakatobi Regency in 2020 is

9.39%, decreased 0.89% compared to 2019 (Statistics

Indonesia, 2021).

Wakatobi Regency is still facing burden both in

infectious and chronic diseases, such as hypertension,

upper respiratory tract infection, diabetes mellitus,

and diarrhoea which ranging from 1,000 to 4,000

number of cases out of 100,000 residents (Badan

Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Wakatobi, 2021). Such

infectious diseases are closely related with the

hygiene and sanitation which is the main concern in

the Planetary Health concept focusing on

environmental issues, such as clean water, and an

adequate sanitation system. Data from Wakatobi

Regency Health Office (2013) showed that the

percentage of healthy sanitation household was

61.18% or equal with 15,111 number in healthy

household sanitation category from the total 24,699

surveyed. According to the same survey, the

percentage of the population with access to clean

drinking water is 73.26% and the percentage of the

population with access to proper sanitation is 67.3%.

This number still far from the target by SDGs goal to

ensure the water availability and sanitation for all.

Moreover, as of COVID-19 implications, basic

handwashing with clean water and soap in every

household is urgently needed.

2.2 Bajau in Wakatobi

The Bajau population has become so widely scattered

in eastern Indonesia not merely because they have

moved around the seas, but also because they have

kept forming maritime creoles in their destinations by

accommodating migrants as well as the native

peoples of various origins (Nagatsu, 2017). Many

scholars who have researched the Bajau communities

found that Bajau people are very consumptive and

good hospitality (Stacey et al., 2018, Suryanegara and

Nahib, 2015, Jeon, 2019). The language of Bajau

people is influenced by local dialects around their

settlement.

The Bajau people are sea nomads currently

scattered in Kalimantan, Sulawesi, the Nusa

Tenggara Islands. Maluku Islands and Eastern Java.

Southeast Sulawesi is the province with the highest

number of Bajau populations (Nagatsu, 2017).

Wakatobi Regency, located in Southeast Sulawesi

Province, is the regency with the highest Bajau

population. In Wakatobi Regency, there are five

Bajau villages: Mola raya, Samplea, Mantigola,

Lohoa, and Lamanggau. The ancestor of these five

Bajau villages was once a descendant of the Bajau

people who lived in Mantigola. In 1963, the

Darul Islam Tentara Islam Indonesia (DI/TII)

Movement or Islamic Armed Force of Indonesia

caused social conflict against the Bajau people in

Wakatobi. In that year the Bajau people scattered to

save themselves to various points which are now new

settlements.

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

216

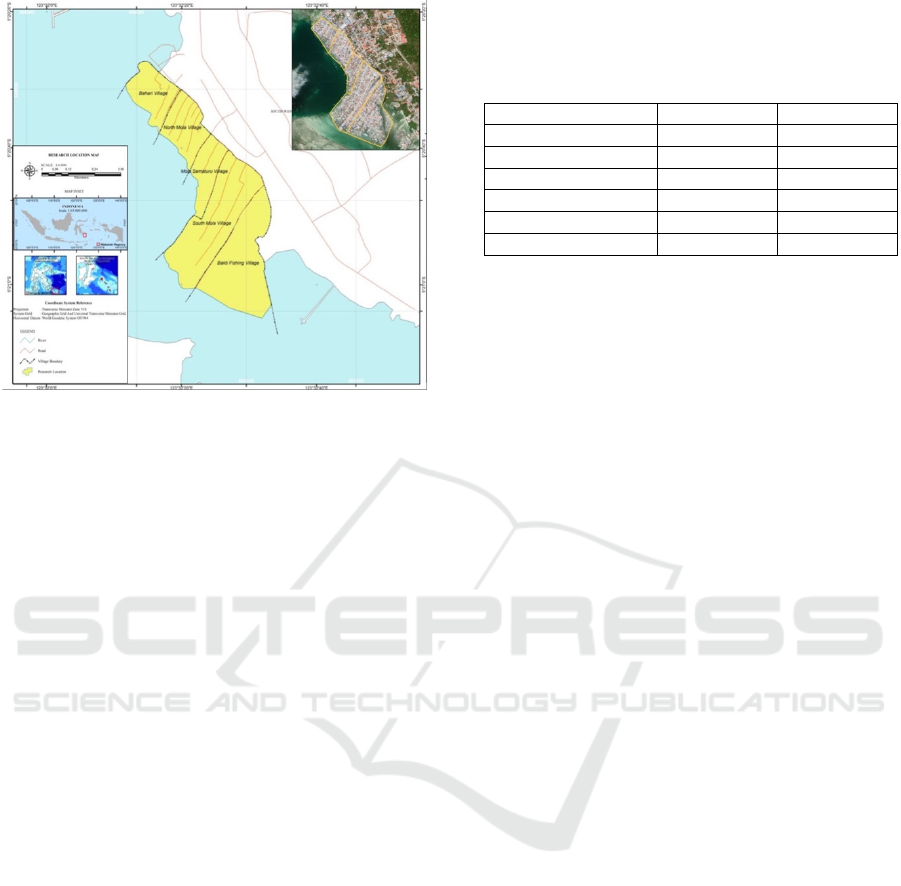

Figure 1: Map of Bajau Mola Raya villages in Wakatobi

Regency (adopted map from (Marlina et al., 2021).

Nowadays, the livelihood of the Bajau people in

Wakatobi Regency is not only as a catch fisherman

but also has a role in the fishery business, the service

sector, and sea transportation. The Bajau people are

also currently going to school and having the equal

socio-economic competitiveness with land

communities. The current consumption and economic

patterns of the Bajau people have followed the land-

oriented communities. The Bajau community's

exposure to information technology has a positive

impact on fishing equipment innovation and business

opportunities. However, the negative impact also

causes the loss of traditional identity as a marine

foraging community that has good adaptability and

resilience to social and environmental changes.

Bajau Mola is the most populous group among

other Bajau villages in Wakatobi Regency.

Administratively, Bajau Mola village consists of five

villages as shown in Table 1. This village is the Bajau

village closest to the district government center called

Wangi-Wangi and is center of fisheries in Wakatobi

Regency. Due to the densely populated and slum

dwellings above the sea, their concern for cleanliness

is very low. The practice of dumping garbage into the

sea and low attention to environmental hygiene is

nowadays a habit of Bajau Mola.

According to the health instructor at the South

Wangi-Wangi subdistrict primary healthcare which

responsible for Bajau Mola villages, the unhealthy

living environment in Mola villages causes several

types of skin diseases such as tinea versicolor,

scabies, scald head and other skin allergies. In

addition, an unclean environment causes a high

incidence of tetanus in Bajau Mola. Meanwhile,

diabetes and hypertension are two diseases that often-

become complaints of Bajau people in Mola.

Table 1: Population of Bajau people in Mola Raya

Village Population Householders

North Mola 995 285

South Mola 1982 546

Bahari 1220 331

Mola Samaturu 891 234

Bakti Fishing 2531 621

Total 7619 2017

Data source: Statistics Indonesia (2021)

According to Khomsan and Syarief (2018),

63.2% of Bajau people in Wakatobi Regency have

more than four household members. Most of the

houses in Bajau Mola are permanent by reclaiming

the sea with coral rocks, only a few houses in the

Bakti Fishing Village still live-in wooden houses that

are staked above the sea and do not have good

sanitation. For the purposes of bathing, washing and

toileting they use sea water. As for the need for clean

water (fresh water) used for drinking and cooking,

they get it by buying. Health issues in Mola Raya are

the nutritional status of toddlers who experience

stunting 48.8%, underweight 32.6% and wasting

9.3% (Khomsan and Syarief, 2018).

2.3 Solid Waste Management

The problem of the relationship between waste,

health, and indigenous peoples is currently a social

phenomenon that needs attention from all parties

since waste is an essential thing generated by every

people. Wakatobi Regency which has a population of

111,402 people with a population growth rate of

1.76% (Statistics Indonesia, 2021) is facing problems

with solid waste management. This problem arises

with the amount of garbage dumped into the sea is

getting higher every year. The available policies that

are not precise in overcoming this problem have also

become a waste problem in Wakatobi which is still

not resolved yet.

In commemoration of Waste Care Day 2018, the

Wakatobi Regency Government launched a

Complete & Sustainable Waste Access Completion

Policy which includes five policy points, namely (1)

creating solid waste entrepreneurs (collection &

reduction of waste), (2) optimizing waste

management, (3) optimization processing of final

disposal sites, (4) village-level cleanliness and waste

reduction competition (Replication Desa Mandiri),

and (4) the annual agenda of the 'Waste Harvest

Festival'. Furthermore, in 2019, the Wakatobi

Planetary Health: A Grassroot Experience of Indonesian Sea Nomads in Solid Waste Management in Bajau Mola Raya, Wakatobi Regency,

Southeast Sulawesi

217

Regency government has ambitions in solid waste

management to achieve the target of 20% reduction

and 80% waste management. Currently, the waste

access rate in Wakatobi Regency is at 57% for

handling and 3% for reduction. As a coastal area that

is often traversed by trans-island shipping vessels,

Wakatobi Regency is not only dealing with garbage

from residents. Marine debris, both from fishermen

and passing passenger ships, is also a complicated

problem faced.

The government of Wakatobi Regency, through

the Department of Environment (DLH) noted that

around 45 tons of waste can be collected per day from

four islands. On the island of Wangi-wangi, the

volume of waste per day reaches 30 tons. The

collected waste, especially plastic waste, which is

mostly household waste from the local community, as

well as garbage shipments from outside the island of

Wakatobi. Of the 45 tons of waste, as much as 30 to

40% is plastic waste, and the rest is non-organic waste

such as fruit peels, corn husks, wood and etc.

In an effort to control waste in Wakatobi

Regency, since December 2018, a circular letter from

the Regent of Wakatobi has been issued regarding the

prohibition of using plastic containers or wraps in all

government activities. Practically, it is not well

managed because of the lack of personal commitment

and habits. For the time being, there is only on the

coast of Wangi-wangi island that cleaning workers

from the DLH has been assigned to keep the entire

beach clean from garbage sent from the sea. The rest

area of Wakatobi assigns their villager to be cleaning

workers which paid by village fund. In one village

there are four to five cleaning workers. Nevertheless,

it seems not quite effective because the cleaning

workers are only oriented to salary over the sense of

belonging to keep environmental clean.

In the main city like Wangi-wangi, the cleaning

workers are DLH’ officers, their job is to maintain the

cleanliness of the entire coastal area, but garbage in

the sea areas has not been significantly cleaned. The

garbage that has been transported from the coast will

be taken to final disposal sites (TPA). In the

appropriate plan, the organic waste will be processed

into compost, and certain types of plastic waste will

be processed into crafts. Moreover, this practice is

just a concept but no longer happening. In addition,

the local government also seeks to raise awareness

about environmental care from an early age, through

the Department of Education in Wakatobi Regency,

using subjects for local content specifically for the

environment.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The existence of local knowledge in the planetary

concept has been implemented by the Bajau people in

their livelihood. This circumstance forces the Bajau

people to adapt to changes in environmental threats

and public health problems, particularly related to

waste management. This study found that several

considerations related to the implementation of

planetary health. In addition, it was found that the

failure of the action and stimulus programs from

various parties that had been working with the Bajau

people in Mola. Government policies and community

awareness regarding solid waste management which

affects environmental and health problems are still

not synergized properly in Wakatobi Regency.

3.1 Local Knowledge and Social

Determinant of Health

The life habits of the Bajau people as marine

colonizers have become a cultural identity known to

the public today. Their local knowledge that has

evolved into a land community has made the Bajau

people in Mola dubbed as people who are confused

by the current advances in information technology.

This evolution is a human-environment interaction

that in an undebatable way affects all aspects of the

life of the Bajau people. The evolution of the local

knowledge can be seen as part of the general self-

organizing process of all-natural systems (Gadgil et

al., 1993). Local knowledge that used to be relied on

to adapt has now turned into a practice that destroys

environmental stability, especially in solid waste

management.

The Bajau people in Mola think that solid waste

management is not a priority issue that they have to

deal with at this time. They think that the garbage that

they deliberately throw into the sea will disappear by

itself and be carried by the ocean somewhere.

Nevertheless, they define the cleanliness of

environment when they do not see garbage in and

around the houses. They do not consider the overall

cleanliness of the sea from garbage and the issue of

marine degradation due to debris as long as they still

can catch fish in the atoll and the other pelagic areas.

The behaviour of throwing garbage into the sea

has existed since their ancestor’s period. Even though

they have known about the sea spirits who prohibit

them to litter. In the past, the waste they disposed

mostly are organic waste but now the types of waste

have varied to plastic, Styrofoam, household

chemicals, and so on. The local wisdom they have

about the sea as their farm and home is not in line with

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

218

their current practice and behaviour. Indeed, the

readiness to become an islander, low participation in

education, and forced adaptation into modern living

are social issues that need to be addressed.

The theory of Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991)

explains that health status or diseases experienced by

individuals is affected by factors located in several

layers of the environment, and most of these health

determinants are alterable factors. This theory is very

supportive to see the phenomena and relationships

between health issues, the environment, and the

practice of waste disposal which could be improved

slowly by providing a consistent understanding to the

Bajau Mola people. Health awareness of the Bajau

people is still low by looking at the ethnocentric point

of view. The Bajau people have term “shaman” but it

is more related to magic spirits. This phenomenon

disconnected in viewing the issue of local knowledge,

planetary health, ecosystem, and community health

that have not been well integrated. Indeed, the social

issues in health have not been included in the waste

reduction points in Wakatobi Regency as shown in

Bajau Mola.

Bajau people realize their failures on

implementing local knowledge, however, they were

rolled into a complex system. The erosion of the

cultural practices of the Bajau people is due to the

adoption of a modern lifestyle and the unrecognition

of Bajau culture and identity collectively by the

Wakatobi Regency government. The destruction is

also exacerbated by the lack in involvement for the

design of community-based environmental education

programs that combine local concepts and

reinforcement with modern concepts especially in

managing waste and its related public health issues.

3.2 Community Participation

Community participation is important in recognizing

the developing social and environmental phenomena.

Community participation entails the problem-solving

caused by various situations. The level of

participation can be revealed from the way the

community overtakes the risks and involvement in

responding to the decisions that have been acted. In

the case of the Bajau Mola, community participation

can be used as the spearhead in solving environmental

and community health problems. The lack of

adaptability and participation in planetary health

cases has made the Bajau Mola tend not to care about

the environment. The invisible social engagement in

the case of the Bajau Mola people has made

environmental and health problems even more

complicated.

In Bajau Mola, the actors of change, whether

young or old, have not been seen to date. Bajau Mola

human resources who are aware of the importance of

environmental and health issues and can educate the

public are still lacking. There are six phenomena

found in this research on social engagement: (1) the

school participation rate is still low; (2) there is no

customary organization that regulates the social

environment; (3) awareness of the damage to the

marine environment due to garbage; (4) the role of the

young generation is still minimal due to the high

number of early marriages; (5) social environmental

programs that enter Bajau Mola are not sustainable;

(6) social discrimination regarding Bajau who are

considered as immigrants.

In another hand, there is a local movement from

multi-stakeholders in Wakatobi Regency which

named Community of Seeing Nature (Kamelia). It is

a consortium of various elements of local government

organizations, NGOs, academics, and

environmentalists. The community's first interest was

focused on the issue of plastic waste management.

One of their working areas is in Mola Raya villages.

The Kamelia embraced a local organization, the

Bajau Mola Tourism Institute (Lepa Mola) to educate

the community by carrying out waste clean-up

actions, waste recycling activities, environmental

education for primary, junior high school students,

and youth organizations. The Kamelia states that the

unavailability of trash cans in each house and the

absence of paid cleaning workers from local

government are the main issues in Bajau Mola.

Therefore, Bajau Mola find it difficult to dispose their

own waste to the garbage dump in the city main road

(land areas).

Regarding to the implementation of planetary

health, the community participation and social

engagement is really matter when working with

indigenous people and local communities (IPLCs)

issues. Ultimately, the individual, community, and

the planet are rooted in traditional systems and

collective knowledge that engages the need for

respect and relationships to the nature-culture system.

3.3 Local Interests in Waste

Management System

Single-use plastics and poor waste management are

relatively new phenomena in remote island

communities in Indonesia (Phelan et al., 2020).

Wakatobi Regency, as an archipelagic area inhabited

by various ethnicities, one of which is the Bajau, is

also facing a complicated waste problem. Of the four

main islands belonging to Wakatobi Regency, only

Planetary Health: A Grassroot Experience of Indonesian Sea Nomads in Solid Waste Management in Bajau Mola Raya, Wakatobi Regency,

Southeast Sulawesi

219

one of them in South Wangi-wangi subdistrict have

adequate TPA. The practice of managing waste is by

burning or throwing it into landfills or sea carelessly.

The case is even worse in the Bajau village, which

incidentally lives on the coast and the sea separately.

The practice of disposing of waste is carried out

directly into the sea. As one of the discussion points,

the government's policy, and seriousness in dealing

seriously with the waste problem in Wakatobi

Regency are factors that support the success of the

planetary health system at the grassroots level.

Associated with the practice of littering, the

Bajau Mola community is one of the community

groups that contribute to environmental pollution by

throwing solid waste directly into the sea (Phelan et

al., 2020). This problem will of course intersect with

the issue of environmental health and the community

itself. The Bajau people as a coastal community with

a complex geography, coupled with a weak waste

collection service system, local interest, and low

plastic literacy make waste management a difficult

problem. This also makes the Bajau Mola people

themselves will bear the impact of the marine plastic

crisis in a certain period.

Furthermore, the political situation in case of

Wakatobi Regency has influenced the mainstreaming

of the introduction of local wisdom and the

mainstreaming of policy directions. Environmental

issues are still associated with local elections and

legislative members which are translated in the form

of and assistance to villages that have won these

political candidates. In the context of acknowledging

local wisdom and the identity of the Bajau

community, Wakatobi Regency has not had it that far.

The assumption and the stigma that is spread about

the Bajau people are labeled to be the actor of

environmental damages for marine living resources

and as low intention people to ecosystem health. As

impacts, Bajau people has a high risk of public health

issues and social blaming regarding their destructive

practices. This is also what makes the Bajau people

lose confidence in the government system, both from

the region and the vertical agency that oversees the

WNP.

The local government's interest in integrated

health issues can be the main point in solving

environmental problems in Bajau Mola. On the other

hand, the Bajau Mola community also needs

cooperation in unifying the existing vision of local

wisdom regarding coastal and marine management,

solid waste management, and environmental health

systems into an integrated concept that should be

reconstructed by the Wakatobi district government.

3.4 Human and Ecosystem Health

Philosophically, the Bajau people recognize the

recommendation to protect the sea because the sea is

the abode of ancestral spirits. If it is damaged, the

Bajau people will get "Pamali" or "Taboo" in the form

of a customary prohibition to take certain actions that

are detrimental to themselves and the community.

Bajau people are prohibited from bathing with soap,

throwing away the rest of the sea drink, using

perfume, throwing chilies in the sea, singing and

making noise in their sacred areas. This concept is

also believed to be a customary-based conservation

practice in the Bajau version, including throwing

garbage into the sea. The fact is that these habits and

beliefs have disappeared with the socio-economic

lifestyle that has been crushed by globalization.

The concept of the relationship between humans

and the environment is the basis of planetary health to

help solve integrated health problems and their

solutions start from the smallest locus in society.

Associated with the issue of solid waste management

in Bajau Mola, this can be seen clearly, where people's

habits of throwing garbage into the sea will damage

the environment and will cause disease and disrupt

public health. In terms of human behavior in the form

of loss of community identity, social recognition, level

of education and external cultural influences, the

behavior of the community in Bajau Mola to dispose

of garbage also increases with time. In terms of

policies and support from local organizations, it also

shows the low level of supervision and poor

management systems in solving waste and

environmental health problems in Wakatobi Regency.

The dynamics of interaction between humans and

the environment in solid waste management in

Wakatobi Regency can be seen from how the Bajau

people adapt, modify, and depend on the

environment, especially the coast and other marine

resources. The generation of Bajau people who have

lost their customary norms and guidelines in

preserving the environment has made this interaction

gap even bigger. The embodiment of local knowledge

into the living system is currently fading in Bajau

Mola. Awareness of the importance of the

environment for human survival has begun to

decrease and is predicted to disappear in the next two

or three generations.

3.5 Implementation of Planetary

Health

The relationship between humans and nature and their

implications for planetary health through the lens of

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

220

traditional ecological knowledge systems is an

integral part of realizing healthy communities and

environment. The traditional ecological knowledge

system itself is based on a proper understanding of the

Natural Law or First Law, the meaning of which is

uniquely rooted in each region globally (Redvers et

al., 2020). Meanwhile, the collapse of the ecological

system is the biggest problem for human health and

survival globally, as felt during the Covid-19

pandemic.

This research argues that the concept of planetary

health is a concept that can reach the smallest social

unit in society if it is implemented with the right

approach with commitment from the government and

other organizations. In the case of implementing

planetary health in Wakatobi Regency with a solid

waste management case study, the commitment of

multi stakeholders is low in solving waste, public

health and environmental problems. This

implementation did not seem well-work, due to the

loss of local wisdom from the Bajau Mola people who

were crushed by the time. Health, safe environment,

cleanliness, and ecosystem sustainability are placed

at the bottom after economic issues by the Bajau Mola

people. If viewed inclusively, there is a gap between

strengthening local wisdom and regional

development goals that are mainstreaming the Bajau

people as fishermen who bear a negative stigma.

As indigenous peoples who engaged with social

environment, rooted in cultural values, political

ideologies, legal and economic systems, ethical

principles, and beliefs, Bajau people are a vulnerable

community regarding planetary health issues. There is

a failure in addressing the interconnection between

human and environmental systems. In current debates,

there is always a need to move beyond science and

technology and address these broader socio-cultural

issues by engaging in economic, legal, and political

work, complementing and supplementing ‘head stuff’

with ‘heart, gut and spirit stuff’, and working from the

grassroots up (Hancock, 2019). At least there is

consideration in the form of innovations that present

the idea of planetary health to the Bajau people in

reducing gaps in current public health policies that fail

to consider key perspectives related to ecology.

Furthermore, increasing cooperation between

governments, non-governmental organizations,

international organizations, academia, private sectors,

and civil society in solving planetary health problems

is mandatory (Paula, 2018).

4 CONCLUSIONS

Planetary health as a phenomenological approach in

viewing the issue of human environment interaction

is very suitable to be implemented in the smallest

social community. In detail, this approach does not

provide concrete steps because each community has

its own uniqueness and challenges. In the case study

of the Bajau Mola people in Wakatobi, the

implementation of the planetary health system in the

example of environmental hygiene and solid waste

management seems inconsistent with the theory.

External conditions and factors related to the

unresolved policies and identity of the Bajau people

make this theory fail in general. Local knowledge,

social determinants of health, community

participation, local interests in waste management

system, human and ecosystem health, and

implementation of planetary health itself is the

consideration of a new integration model for

Wakatobi Regency in implementing planetary health

in the case of solid waste management. Furthermore,

reconstructing the definition of human progress and

situated problem, redesigning human-environment

interaction probabilities, and revitalizing the

prospects for the human health civilizations in the

policy direction are the recommended consideration

that proposing in this research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research work was supported by Doctoral

Dissertation research scholarship for the 90th

Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund

(Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund)

Batch# 46 Round 2/2020 Academic Year 2019

granted by Chulalongkorn University.

REFERENCES

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Wakatobi. (2021).

Kabupaten Wakatobi dalam Angka 2021 (Wakatobi

Regency in Figures 2021).

Behera, M. R., Behera, D. & Satpathy, S. K. (2020).

Planetary health and the role of community health

workers. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary

Care, 9, 3183.

Berkes, F. (1993). Traditional ecological knowledge in

perspective. Traditional ecological knowledge:

Concepts and cases, 52.

Capon, A. (2020). Understanding planetary health. The

Lancet, 396, 1325-1326.

Planetary Health: A Grassroot Experience of Indonesian Sea Nomads in Solid Waste Management in Bajau Mola Raya, Wakatobi Regency,

Southeast Sulawesi

221

Clifford, K. L. & Zaman, M. H. 2016. Engineering, global

health, and inclusive innovation: focus on partnership,

system strengthening, and local impact for SDGs.

Global health action, 9, 30175.

Clifton, J. & Unsworth, R. K. F. (2009). Introduction. In:

CLIFTON, J., UNSWORTH, R. K. F. & SMITH, D. J.

(eds.) Marine Research and Conservation in the Coral

Triangle: the Wakatobi National Park. Australia: Nova

Science Publishers Inc.

Dahlgren, G. & Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and

strategies to promote social equity in health.

Background document to WHO-Strategy paper for

Europe. Institute for Futures Studies.

Dickerson, D., Baldwin, J. A., Belcourt, A., Belone, L.,

Gittelsohn, J., Kaholokula, J. K. a., Lowe, J., Patten, C.

A. & Wallerstein, N. (2020). Encompassing cultural

contexts within scientific research methodologies in the

development of health promotion interventions.

Prevention Science, 21, 33-42.

Elliott, G., Mitchell, B., Wiltshire, B., Manan, I. A. &

Wismer, S. (2001). Community participation in marine

protected area management: Wakatobi National Park,

Sulawesi, Indonesia. Coastal Management, 29, 295-

316.

Finn, S., Herne, M. & Castille, D. (2017). The value of

traditional ecological knowledge for the environmental

health sciences and biomedical research.

Environmental health perspectives, 125, 085006.

Gadgil, M., Berkes, F. & Folke, C. (1993). Indigenous

knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio, 151-

156.

Hancock, T. (2019). Beyond science and technology:

Creating planetary health needs not just ‘head stuff’, but

social engagement and ‘heart, gut and spirit’stuff.

Challenges, 10, 31.

Horton, R., Beaglehole, R., Bonita, R., Raeburn, J., McKee,

M. & Wall, S. (2014). From public to planetary health:

a manifesto. The Lancet, 383, 847.

Horton, R. & Lo, S. (2015). Planetary health: a new science

for exceptional action. The Lancet, 386, 1921-1922.

Horwitz, P. & Parkes, M. W. (2019). Intertwined strands

for ecology in planetary health. Challenges, 10, 20.

Jeon, K. (2019). The Life and Culture of the Bajau, Sea

Gypsies. Journal of Ocean and Culture, 2, 38-57.

Khomsan, A. & Syarief, H. (2018). Studi Ketahanan

Pangan Rumah Tangga Suku Bajau di Kepulauan

Wakatobi Sulawesi Tenggara. Bogor Agricultural

University (IPB).

Lerner, H. & Berg, C. (2017). A comparison of three

holistic approaches to health: one health, ecohealth, and

planetary health. Frontiers in veterinary science, 4,

163.

Marlina, S., Astina, I. K. & Susilo, S. (2021). Social-

economic adaptation strategies of Bajau mola fishers in

Wakatobi national park. GeoJournal of Tourism and

Geosites, 34, 14-19.

Myers, S. S. (2017). Planetary health: protecting human

health on a rapidly changing planet. The Lancet, 390,

2860-2868.

Nagatsu, K. (2017). Maritime Diaspora and Creolization:

Genealogy of the Sama-Bajau in Insular Southeast

Asia. Senri Ethnological Studies, 95, 35-64.

Paula, N. D. (2018). What is planetary health? Addressing

the environment-health nexus in Southeast Asia in the

era of the Sustainable Development Goals:

opportunities for International Relations scholars.

Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 61.

Phelan, A., Ross, H., Setianto, N. A., Fielding, K. &

Pradipta, L. (2020). Ocean plastic crisis—Mental

models of plastic pollution from remote Indonesian

coastal communities. PloS one, 15, e0236149.

Rathgeber, B., & Kirana, P. W. (2018). Wakatobi

Guidebook: Guide to Discovering The World Marine

Heritage of Southeastern Sulawesi.

Redvers, N. (2018). The value of global indigenous

knowledge in planetary health. Challenges, 9, 30.

Redvers, N., Poelina, A., Schultz, C., Kobei, D. M.,

Githaiga, C., Perdrisat, M., Prince, D. & Blondin, B. s.

(2020). Indigenous natural and first law in planetary

health. Challenges, 11, 29.

Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis, Sage.

Stacey, N., Steenbergen, D. J., Clifton, J. & Acciaioli, G.

2018. Understanding social wellbeing and values of

small-scale fisheries amongst the Sama-Bajau of

archipelagic Southeast Asia. Social Wellbeing and the

Values of Small-scale Fisheries. Springer.

Statistics Indonesia. (2019). Statistical Data of Wakatobi

Regency Wakatobi: BPS Kabupaten Wakatobi.

Suryanegara, E. & Nahib, I. (2015). Perubahan Sosial Pada

Kehidupan Suku Bajau: Studi Kasus Di Kepulauan

Wakatobi, Sulawesi Tenggara. Majalah Ilmiah Globe,

17, 67-78.

Wakatobi Regency Health Office. (2013). Health Profile of

Wakatobi Regency. Retrieved from

https://pusdatin.kemkes.go.id/resources/download/prof

il/PROFIL_KES_PROVINSI_2013/28_Prov_Sultra_2

013.pdf

White, A. T., Aliño, P. M., Cros, A., Fatan, N. A., Green,

A. L., Teoh, S. J., Laroya, L., Peterson, N., Tan, S. &

Tighe, S. (2014). Marine protected areas in the Coral

Triangle: progress, issues, and options. Coastal

Management, 42, 87-106.

Wianti, N. I., Dharmawan, A. H. & Kinseng, R. (2012).

Local Capitalism of Bajau. Sodality: Jurnal Sosiologi

Pedesaan, 6.

ICSDH 2021 - International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

222