College Students Perspective on Online Learning during COVID-19:

A Systematic Literature Review

Isnaeni Anggun Sari

1

and Muhammad Zulfa Alfaruqy

2

1

Master of Psychology, Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia

Keywords: College Student, COVID-19 Pandemic, Perspective, Online Learning.

Abstract: COVID-19 has changed the behavior and habits of society around the world, including in the education aspect.

Education is transformed from face-to-face learning to online learning. This study examined previous articles

on college students' perspectives of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. PRISMA guideline was

used as the research method. The database used was Google Scholar with the search keywords of “Online

learning” AND “College student perspective” OR “Undergraduate student perspective” OR “University

student perspective” AND “Covid-19”. The authors found 30 articles in which only five met the criteria and

quality. The results showed that college students had opinions regarding the importance of preparation in

online learning. Students had negative and positive perspectives on online learning. The negative perspective

stemmed from technical problems such as internet and electricity problems, expensive data plans, and

psychological problems (fluctuations in motivation, boredom, and stress). While, the positive perspective

stemmed from valuable experience in expanding technological exploration and developing soft skills

(discipline, responsibility, creativity, and independence). College students argued that online learning was the

best choice during the COVID-19. They showed a preference for face-to-face learning than online learning if

the circumstances have improved. The research has implications for educational policies at the macro and

micro levels to improve the learning system that pays attention to students' psychological well-being and

maintains the quality of education.

1 INTRODUCTION

All countries are currently struggling to face the

Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

COVID-19 was first discovered in Wuhan, Hubei,

China, in December 2019 (Hu et al., 2020). The

people infected with this virus show general

symptoms of fever, shortness of breath, dry cough,

fatigue, and typical symptoms of pain, headache,

diarrhea, and loss of smelling sense (Alshukry et al.,

2020). The virus spread very quickly to various parts

of the world. It forced the World Health Organization

(WHO) to raise the status to global pandemic starting

March 2020 (Rafique et al., 2021).

Countries have also established public policies to

reduce the transmission rate of COVID-19 (Chen et

al., 2020). Indonesia, in particular, has implemented

PSBB (Pembatasan Sosial Berskala besar, Large-

Scale Social Restrictions) and PPKM (Pemberlakuan

Pembatasan Kegiatan Masyarakat, Micro

Enforcement of Community Activity Restrictions).

PPKM consists of level 1-4. WHO recommends the

government to implement health protocols such as

wearing masks, washing hands, maintaining distance,

staying away from crowds, and reducing community

mobility. Some activities that are usually carried out

face-to-face have been transformed into online.

One of the most affected aspects by the pandemic

is education (Sulata & Hakim, 2020; Biswas et al.,

2020; Martinez-Munoz et al., 2021). At least 1.725

billion students are affected due to the school and

college buildings closing. In Indonesia, the Ministry

of Education and Culture (2020) prohibits

universities from conducting face-to-face learning

and instructs universities to conduct online learning.

Several countries, including Egypt, France, Italy, the

United States, and the United Arab Emirates,

orchestrate distance learning using online platforms.

While China, South Korea, Iran, Rwanda, Thailand,

and Peru use the MOOC (Massive Open Online

Course) system which learning materials are provided

through applications, television, or other media,

Sari, I. and Alfaruqy, M.

College Students Perspective on Online Learning during COVID-19: A Systematic Literature Review.

DOI: 10.5220/0010810800003347

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Psychological Studies (ICPsyche 2021), pages 219-227

ISBN: 978-989-758-580-7

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

219

allowing the teachers to access the network (Chang &

Yano, 2020). This condition has encouraged research

on online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Online learning is a form of learning that brings

students and lecturers to carry out academic activities

using the internet (Kuntarto, 2017). Mobile phones,

laptops, and internet connections are important

facilities in online learning. Adedoyin & Soykan

(2020) argued that technological infrastructure and

digital competencies are the primary keys to online

learning. A suitable platform is also needed by every

university organizing online learning (Masoud &

Bohra, 2020). Platforms often used to support the

online learning process are Zoom, Microsoft Teams,

Google Meet, and Google Classroom. Numerous

platforms with supporting features can be attractive

choices for lecturers and students during the COVID-

19 pandemic (Abidah et al., 2020).

Online learning focuses on controlling students;

thus, the approach used is student-centered learning.

College students have full responsibility and

autonomy in the learning process and actively

develop their knowledge based on the previous one

(Jacobs et al., 2016; Yuliani et al., 2020). Sadikin &

Hamidah (2020) found that online learning lost

lecturers and college students' face-to-face

interaction, facilitated students’ learning

independence, and increased student motivation.

Lecturers can transfer information to students via

lecture materials, individual assignments, group

assignments, and quizzes. According to Jamaluddin

et al. (2020), online learning has both advantages and

challenges. Argaheni (2020) stated that online

learning was quite confusing for students, hindered

student comprehension, made students passive, less

creative, and productive, also triggered stress.

Several terms similar to online learning have been

introduced in recent decades—for instance, e-

learning, distance learning, and blended learning

(Moore et al., 2011). Along with the COVID-19

pandemic, various countries researched to describe

the condition of students concerning the utilization of

e-learning (Kaur et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2021),

distance learning (Masoud & Bohra, 2020; Turner et

al., 2020; Hapsari, 2021), and blended learning (Lim

& Wang, 2016).

Many studies have overlapped the terms online

learning, e-learning, distance learning, and blended

learning (Kimkong & Koemhong, 2020). It creates

confusion in assessing how students' perspectives on

online learning are during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Online learning in this study explicitly referred to

learning that lecturers and students carry out fully and

synchronously. Full online learning is certainly not

the same as blended learning. Blended learning refers

to a combination of face-to-face learning and online

learning (He et al., 2014). The synchronous refers to

learning that is carried out simultaneously through

electronic media. Synchronous provides teachers and

students to interact directly (Perveen, 2016).

An assessment of previous research is needed in

the field of education. This research objective was to

examine the previous studies on student perspectives

regarding online learning during the COVID-19

pandemic. The research focused on answering the

question of “What is the student's perspective on

online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic?”.

2 METHOD

The purpose of this study was to examine previous

studies on college student perspectives on online

learning during the COVID-19 pandemic using the

systematic review literature method. The research

design was a systematic literature review referring to

the PRISMA (Prefferens Reporting Items for

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) guidelines

(Page et al., 2021). We used the Google Scholar

database. We searched by writing keywords relevant

to the topic, which were “Online learning” AND

“College student perspective” OR “Undergraduate

student perspective” OR “University student

perspective” AND “Covid-19”.

The articles found would be reviewed based on

the following criteria: 1) full-text articles; 2) research

articles from 2020-2021; 3) articles written in

English; 4) the participants were college students; 5)

the research used quantitative and/or qualitative

designs; 6) the research focused on college students

perspective of online learning during the COVID-19

pandemic.

The article searching process was done on June

25, 2021. We found 30 articles on Google Scholar

with the keywords of “Online learning” AND

“College student perspective” OR “Undergraduate

student perspective” OR “University student

perspective” AND “Covid-19”. Seven articles were

excluded because they were not in full text and did

not use English. The remaining 23 articles were

reviewed. However, 18 had to be excluded because

they were irrelevant, did not have a clear journal

identity, and did not constitute empirical research.

The participants also did not meet the inclusion

criteria. The remaining five articles were processed

because they had suitable participants, research

designs, and discussed online learning perspectives of

students during the Covid-19 pandemic. The five

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

220

articles were quality-checked using the CASP

Qualitative Checklist for qualitative research and

EPHPP for quantitative research. Two articles were

checked for quality using the CASP Qualitative

Checklist by referring to the previously mentioned

quality check. Three other articles were quality-

checked using EPHPP.

The CASP Qualitative Checklist has several

criteria that must be fulfilled by the article, as follows:

1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the

research?

2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate

(proper methodology for addressing the

research goal)?

3. Was the research design appropriate to address

the aims of the research?

4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to

the aims of the research?

5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed

the research issue?

6. Has the relationship between researcher and

participants been adequately considered?

7. Have ethical issues been taken into

consideration?

8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

9. Is there a clear statement of findings?

10. How valuable is the research?

According to the CASP Qualitative Checklist, two

articles met the criteria and could be categorized as

good. The first article was by Hanum (2020) entitled

“Character Education in Online Learning on

Citizenship Education (College Student's

Perspective)”, categorized as qualitative research

with good quality. The article was categorized as

good quality because it did not meet CASP criteria

number 6 and 7. Furthermore, the second article was

done by Turner et al. (2020) entitled “How to Be

Socially Present When the Class Becomes "Suddenly

Distant"”. It was categorized as a good quality

qualitative research because the article did not meet

criteria number 6.

The other three quantitative research articles were

checked using EPHPP. Some of the criteria that must

be fulfilled are as follows;

1. Selection bias

2. Study design

3. Confounders

4. Blinding

5. Data collection methods

6. Withdrawals and drop-outs

The three articles met the criteria and could be

categorized as good quality. The first article was a

quantitative study by Rana and Garbuja (2021) titled

“Nursing Students' Perception of Online Learning

Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic”. The article has a

strong category score on criteria number 1, 2, 5, and

6. The second article was by Puspandari et al. (2020),

titled “Online Learning During a Pandemic: A Web

Based Survey from Student Perspective” which was

categorized as a good quality article. The article met

five criteria with a strong category score: criteria

number 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6.

Furthermore, a quantitative research article by

Al-Amin et al. (2021) titled "Status of Tertiary Level

Online Class in Bangladesh: Students Response on

Preparedness, Participation, and Classroom

Activities” was categorized as a good quality article.

The article had a strong category score in criteria

number 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6. Thus, the five quality-

checked articles would be included in a systematic

review in this study. The process of article searching

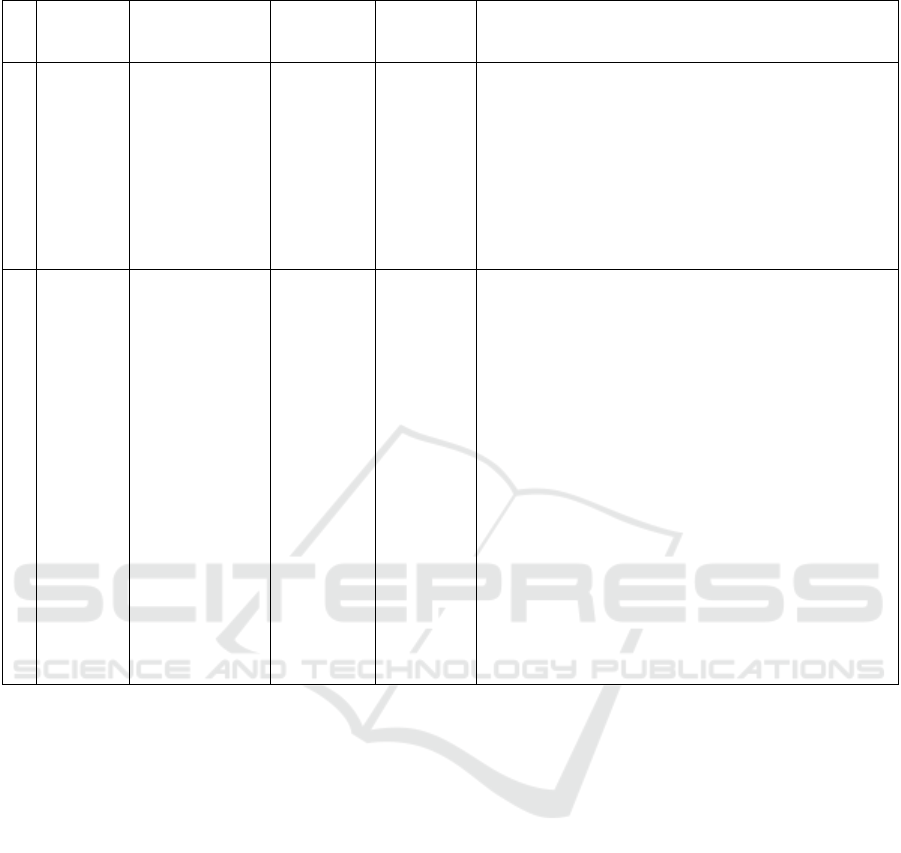

can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Article selection flow.

Record

identified

through

Google

Scholar (n=

30)

Record excluded

(n= 7)

a. Article not in

full text (n= 4)

b. Non-English

article (n= 3)

Record

screening

(n= 23)

Record excluded

(n=18)

a. Irrelevant

article (n=13)

b. Unclear

journal identity

article (n= 1)

c. Non empirical

research article

(n=1)

d. Non student

participants

(n= 3)

Record

assessed for

eligibity

(n= 15)

Identification

Screening

Eligibity

Do not find

articles that not

fulfil the quality

Article

included for

review (n= 5)

Included

College Students Perspective on Online Learning during COVID-19: A Systematic Literature Review

221

3 RESULT

Table 1: Article review summary.

No Author Participant

and

Country

Method Instrument Result

1 Hanum

(2020)

Participant:

Class leader

students in

five study

programs at

Yogyakarta

State

University

participated

in online

Citizenship

Education

lessons.

Country:

Indonesia

Qualitative a. Interviews

b. Documentation

College students believed that online learning improved

their understanding and technology skills, especially on

the used learning platforms. In addition, online learning

could also instill values of religiosity, discipline,

responsibility, democracy, honesty, independence, and

creativity. Religiosity through routine prayer activities

before and after learning. Discipline through punctuality

in starting and ending learning. Responsibility through

lecture rules, presentation of material, and self-study.

Democracy through the habit of respecting opinions and

deliberation between the course participants. Honesty

through the habit of being honest in presence.

Independence through the habit of seeking and

understanding material independently. Moreover,

creativity through the freedom of expression in

expressing ideas and exploring in utilizing technology.

2 Turner et

al. (2020)

Participant:

16 graduate

students at

the US

universities

Country: UK

Qualitative Semi-structured

interviews

All college students considered the change of learning

practices to online developed various obstacles.

Constraints faced by students include the stability of the

internet network, the use of virtual backgrounds on the

Zoom application, and communication in the classroom.

Students felt awkward due to the difficulty in deciding the

moment to spoke. Students' lack of transition time during

online learning was also a challenge, affecting their

mental readiness to stay focused on learning. The lack of

motivation to participate in the online learning process

reduced their motivation, affecting their reluctance to

participate in classroom activities. Online learning could

also disrupt the students’ concentration because they

were not placed in a conducive classroom.

3 Rana &

Garbuja

(2021)

Participant:

211 nursing

students

from

LMCTH

Country:

Nepal

Quantitative Self-

administered

structured

questionnaire

College students regarded online learning from several

aspects: effectiveness, convenience, obstacles,

differences with face-to-face learning, and satisfaction.

Most of the students perceived online learning as

effective, shown by the following aspects: informative

(71.1%), relevance (64.9%), and learning content and

usefulness (62.1%). More than half of students thought

online learning was easy to understand and convenient

(58.3%). Students found the obstacles that emerged

during online classes were related to the inadequacy of

practical courses (57.8%), motivational inconsistency

(54.0%), unstable internet connection (42.7%), and

expensive data plans (39.8%). Although most students

discovered online learning was effective, they still

thought face-to-face learning was more effective

(59.7%). Students were satisfied with the preparation of

the lecturers (75.4%) and the quality of learning (63%).

Overall, 56.9% of college students had a positive

perspective on online learning.

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

222

Table 1: Article review summary (cont.).

No Author Participant and

Country

Method Instrument Result

4 Puspandari

et al.

(2020)

Participant:

154 postgraduate

students from the

public health

study program.

Country:

Indonesia

Quantitative Online

survey

College students answered that online learning platforms

were easy to use (96.1%), especially Zoom, which

supported synchronous online learning (93.5%). The

feelings that arose in students during online learning

include enthusiasm (54.5%), boredom (48.1%), and stress

(23.4%). 76% of students were satisfied with online

learning. 24% were dissatisfied due to unstable internet

connection and physical fatigue from staring at the screen

and sitting for long.

5 Al-Amin

et al.

(2021)

Participant:

844 students from

various

universities in

Bangladesh

Country:

Indonesia

Quantitative Online

survey

College students believed that the urgency of preparation

in online learning was necessary. The preparation was of

electricity (97%), gadget availability (93%), and internet

connection (75%). Technical preparation supported

psychological readiness. Even though well-prepared,

some students often encountered technical issues during

class, namely unstable internet connections (75%) and

electricity problems (51%). Online learning facilitated

students to ask questions (82%), but it was not easy to

focus on understanding the material. Students living in

the urban area appeared to be superior to students living

in rural areas in all factors: electricity, internet

connection, gadget availability, perception of class order,

understanding the lecture material. 85% of students had a

positive perspective on online learning because it allowed

them to meet and discuss during the class amidst the

COVID-19 pandemic situation. On the other hand, those

who perceived it as unfavorable were having difficulties

maintaining focus and understanding the material.

4 DISCUSSION

Online learning is possible in education. It offers

accessibility, flexibility, connectivity, and the ability

to obtain and present information in the learning

process (Moore, Dickson-Deane, & Galyen, 2011). It

explains why most educational institutions consider

online learning as an important part of their

educational strategy (Allen & Seaman, 2011). The

concept of online learning has been around for the last

few decades, and applications have overgrown during

the COVID-19 pandemic. Online learning answers

the challenges of public policy in various countries

focusing on suppressing the spread of COVID-19

(Chen et al., 2020).

Preparation of Online Learning

The systematic literature review assessed previous

empirical studies on college students in Indonesia,

Bangladesh, Nepal, and the UK. The research

findings indicated that students needed to prepare

technically for online learning, such as electricity,

availability of devices, and internet connections (Al-

Amin et al., 2021). Before the covid-19 pandemic,

students had done the key to online learning, as found

by Parsazadeh et al. (2013), to ensure the accessibility

of students and lecturers and the availability of

various online tools. Technical readiness supported

the psychological readiness of students to focus more

on learning (Turner et al., 2020). Thus, there was a

probability of more psychological unpreparedness in

students who did not prepare for technical matters.

Negative Perspective among College Students

The negative perspective of students towards online

learning consisted of two things: technical problems

and psychological problems. Students often had

unstable internet networks (Turner et al., 2020; Rana

College Students Perspective on Online Learning during COVID-19: A Systematic Literature Review

223

& Garbuja, 2020; Al-Amin, 2021), sudden electricity

cut out (Al-Amin et al., 2021), and expensive data

plans (Rana & Garbuja, 2020). Adedoyin & Soykan

(2020) supported the previous statement. They

reported that the main problem in online learning was

related to technological infrastructure and digital

competencies.

Online learning is considered more difficult in

practical courses than theoretical courses (Rana &

Garbuja, 2020). Lecturers can make efforts to provide

learning modules to solve these difficulties. Yahaya

(2021) found that in practical courses, learning

modules were needed by students. Thus, the mastery

of lecturer skills in preparing learning modules can

solve the needs of students.

College students experienced fluctuation in

learning motivation (Turner et al., 2020; Rana &

Garbuja, 2021), boredom, and stress (Puspandari et

al., 2020). Fluctuations in motivation, boredom, and

stress would affect the condition of college students

in maintaining focus and understanding materials

(Al-Amin et al., 2021) alongside involving

themselves in activities during online learning

(Turner et al., 2020).

Based on research by Basak dan Sinha (2020),

online learning made college students study by

themselves, leading to loneliness and missing social

interactions during face-to-face learning. This

condition increased the chances of depression,

especially in female students. Social support from

significant others, especially family and peer groups,

was a component that needed to be ensured in online

learning. According to Bijeesh (2017), the absence of

peer groups who assisted in reminding the students

about assignments increased distraction and the

opportunity to forget about the deadline for collecting

assignments. It made online learning a big challenge

for students who procrastinated and could not meet

the deadline.

Positive Perspective among College Student

Besides negative perspectives, college students also

had a positive perspective of online learning. Online

learning could encourage students to expand

technology exploration (Hanum, 2020). Students

were encouraged to understand the platforms used for

learning, such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google

Meet, and Google Classroom. Students could also

study every feature on the platform to listen to

material explanations from lecturers, establish

interactive lecturer-student interactions, present

assignments, and take exams.

Online learning also improved several soft skills,

including discipline, responsibility, democracy,

creativity, and independence (Hanum, 2020). For

example, they were expressing brilliant ideas by

utilizing technology and understanding lecture

material independently. Online learning could change

passive learning into active learning. Teacher-

centered learning was transformed into student-

centered learning, where students had to be

independent in their learning (Ramlogan et al., 2014).

The thing that lecturers needed to pay attention to in

facilitating attractive learning designs and

opportunities for college students to express ideas

(Puspandari et al., 2020).

Evaluation of Online Learning

This study also evaluated online learning practices

among college students. The students evaluated

online learning, either positively or negatively, as the

best alternative during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is

related to other studies of internet-based learning

during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the use of e-

learning (Khan et al., 2021), m-learning (Yahaya et

al., 2021), and remote teaching (Martinez-Munoz,

2021; Oumar et al., 2021). Online learning is

considered an effective middle way to continue

teaching and learning activities but still supports

public policies in reducing the spread of COVID-19

(Herliandry et al., 2020).

Most college students were satisfied with online

learning (Puspandari et al., 2020; Rana & Garbuja,

2020). The reasons for satisfaction included the

preparation of lecturers and the implementation of

learning. The experience of participating in face-to-

face learning before the COVID-19 pandemic opened

up opportunities for comparison mechanisms.

Although satisfied with online learning, students

deemed face-to-face learning to be more effective

than online (Rana & Garbuja, 2020). These findings

were similar to research from Kaur (2020), which

found that 86.4% of 267 Indian students agreed that

face-to-face learning was more effective than online

learning.

Improving the Implementation of Online Learning

This paper provided a record of online learning

practices that could be considered for the education

system at the micro and macro levels. First, the

urgency to understand student diversity. The diversity

of student backgrounds was a necessity that could not

be denied. Research from Al-Amiin (2021) showed

that students who lived in urban areas were superior

in several aspects to students who lived in rural areas.

The superiority included the facilitation of electricity,

internet connection, gadgets' availability, class order

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

224

perception, and understanding of lecture material.

The research conducted in Bangladesh was not too

different from what happened in Cambodia. Teachers

and students in rural Cambodia did not have reliable

internet access and technology operation skills,

making it difficult to implement online learning and

leading to an unpleasant experience (Jalli, 2020).

Second, the urgency of understanding platforms

that facilitate online learning. Research from

(Puspandari et al., 2020) found that the Zoom

platform was considered effective by students

(93.5%) in supporting synchronous online learning.

There are two types of online learning, namely

asynchronous and synchronous (Hratinski, 2008).

Synchronous learning refers to learning carried out

simultaneously through electronic media.

Synchronous learning provides an opportunity for

direct interaction between lecturers and students

(Perveen, 2016). While asynchronous learning, which

is not the focus of this research, refers to learning

carried out by indirectly giving teaching materials and

assignments. This learning can be done without

bringing together lecturers and students at the same

time.

Third, the urgency of understanding the level of

student motivation in online learning interactions.

Research from Turner et al. (2020) showed that some

college students sometimes found it hard to determine

the moment to speak or be actively involved in

discussions. It is related to research from

Vanslambrouck et al. (2018) regarding student

motivation using Self-Determination Theory (SDT),

which showed that students could be motivated in

different ways. Several types of motivation in the

perspective of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) can

be considered: (1) Intrinsic motivation, in which

students grow by themselves because they carry out

learning activities that are suitable for pleasure, (2)

Motivation created by rules, which are created in

learning system in which these rules bind students, (3)

Motivational external regulation, which encourages

students to learn to obtain positive results or avoid

negative results.

5 CONCLUSION

Online learning is a necessity in the education system,

especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. College

students considered the urgency of preparation in

online learning. The technical preparation of students

could support their mobility and increase their

psychological readiness. Students perceived online

learning during the COVID-19 pandemic negatively

and positively after experiencing it. Negative

perspectives were caused by technical problems such

as internet and electricity problems, expensive data

plans, and psychological problems (fluctuations in

motivation, boredom, and stress). The positive

perspective was created based on valuable experience

in expanding technology exploration and developing

soft skills (discipline, responsibility, creativity, and

independence). College students believed that online

learning was the best choice during the COVID-19

pandemic. However, they preferred face-to-face

learning over online when circumstances had

improved. It is essential for education providers,

especially lecturers, to understand student diversity,

accessible platforms for students to use, and student

motivation.

This systematic literature review has implications

for policies in education, both at the macro and micro

levels, to continuously improve the learning system.

The learning system needs to pay attention to and care

about students' psychological well-being and meet the

demands of the education quality. Future researchers

interested in the theme of online learning research can

explore other important aspects of the learning

process, for example, the educator's perspective, the

perspective of the student's social environment, or the

effectiveness of online tools.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to express their gratitude to

Faculty of Psychology, Diponegoro University for

supporting the implementation of this research. The

research was conducted without any conflict of

interest.

REFERENCES

Abidah, A., Hidaayatullaah, H. N., Simamora, R. M.,

Fehabutar, D., & Mutakinati, L. (2020). The Impact of

covid-19 to Indonesian education and its relation to the

philosophy of “Merdeka Belajar.” Studies in

Philosophy of Science and Education, 1(1), 38–49.

https://doi.org/10.46627/sipose.v1i1.9

Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic

and online learning: The challenges and opportunities.

Interactive Learning Environments, 0(0), 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

Al-Amin, M., Zubayer, A. Al, Deb, B., & Hasan, M. (2021).

Status of tertiary level online class in Bangladesh:

students’ response on preparedness, participation and

classroom activities. Heliyon, 7(1), e05943.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05943

College Students Perspective on Online Learning during COVID-19: A Systematic Literature Review

225

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2011). Going the distance:

Online eduation in the US, 2011. Sloan Consortium, 44,

1–44.

Alshukry, A., Ali, H., Ali, Y., Al-Taweel, T., Abu-Farha,

M., AbuBaker, J., Devarajan, S., Dashti, A. A., Bandar,

A., Taleb, H., Bader, A. Al, Aly, N. Y., Al-Ozairi, E.,

Al-Mulla, F., & Abbas, M. B. (2020). Clinical

characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-

19) patients in Kuwait. PLoS ONE, 15(11), 1–16.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242768

Argaheni, N. B. (2020). Sistematik review: Dampak

perkuliahan daring saat pandemi COVID-19 terhadap

mahasiswa Indonesia. PLACENTUM: Jurnal Ilmiah

Kesehatan Dan Aplikasinya, 8(2), 99-108.

https://doi.org/10.20961/placentum.v8i2.43008

Basak, Rituparna, & Sinha, D. (2020). Association

between interpersonal social support and perceived

depression among undergraduate college students of

Kolkata during unlock phase of COVID-19 lockdown.

EAS Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences,

2(6), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.36349/easjpbs.20

20.v02i06.003

Bijeesh, N. A. (2017). Advantages and disadvantages of

distance learning. Indiaeducation. http://www.india

education.net/online-education/articles/advantages-

and-disadvantages-of-distance-learning.html

Biswas, B., Roy, S. K., & Roy, F. (2020). Students

perception of mobile learning during COVID-19 in

Bangladesh: University student perspective.

Aquademia, 4(2), ep20023. https://doi.org/10.29333/

aquademia/8443

CASP qualitative checklist. (2018). Critical Appraisal

Skills Program (CASP). https://casp-uk.net/wp-

content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-

2018.pdf

Chen, B., Liang, H., Yuan, X., Hu, Y., Xu, M., Zhao, Y.,

Zhang, B., Tian, F., & Zhu, X. (2020). Roles of

meteorological conditions in COVID-19 transmission

on a worldwide scale. BMJ Open, 1-18.

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.16.20037168

Chang, G. C., & Yano, S. (2020). How are countries

addressing the Covid-19 challenges in education?

A snapshot of policy measures. Retrieved from

World Education Blog:https://gemreportunesco.word

press.com/2020/03/24/how-are-countries addressing-

the-covid-19-challenges-in-education-a-snapshot-of-

policy-measures/

EPHPP. (2015). Appendix A: Effective Public Health

Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for

Quantitative Studies. Springer Briefs in Public Health,

45–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17284-2

Hanum, F. F. (2020). Character education in online

learning on citizenship education (college student’s

perspective). Advances in Social Science, Education

and Humanities Research, 524, 89–93.

https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210204.013

Hapsari, C. T. (2021). Distance learning in the time of

Covid-19: Exploring students’ anxiety. ELT Forum:

Journal of English Language Teaching, 10(1), 40–49.

https://doi.org/10.15294/elt.v10i1.45756

He, W., Xu, G., & Kruck, S. E. (2014). Online is education

for the 21st century. Journal of Information Systems

Education, 25(2), 101–105.

Herliandry, L. D., Nurhasanah, N., Suban, M. E., &

Kuswanto, H. (2020). Pembelajaran pada masa

pandemi COVID-19. JTP - Jurnal Teknologi

Pendidikan, 22(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.21009/

jtp.v22i1.15286

Hu, B., Guo, H., Zhou, P., & Shi, Z. L. (2020).

Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19.

Nature Reviews Microbiology, 1-14. https://doi.org/

10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7

Hratinski, S. (2008). A study of asynchronous and

sycnchronous e learning methods discovered that each

supports different purposes. Educase Quarterly, 31,

51-53.

Jacobs, G. M., Renandya, W. A., & Power, M. (2016).

Simple, powerful strategies for student centered

learning. Springer.

Jalli, N. (2020, Maret 11). Lack of internet access in

Southeast Asia poses challenges fir students to study

online amid COVID-19 pandemic. The Conversation.

https://theconversation.com/lack-of-internet-access-in-

southeast-asia-poses-challenges-for-students-to-study-

online-amid-covid-19-pandemic-133787

Jamaluddin, D., Ratnasih, T., Gunawan, H., & Paujiah, E.

(2020). Pembelajaran daring masa pandemik Covid-19

pada calon guru : Hambatan, solusi dan proyeksi. Karya

Tulis Ilmiah UIN Sunan Gunung Djjati Bandung, 1–10.

http://digilib.uinsgd.ac.id/30518/

Kaur, H., Narang, R., Shinh, A.S., Singla, M., Nadaf, I &

Kumar, P. (2021). Perceptions of students regarding

online classes – adapting the new normal. 7(1), 67–70.

https://doi.org/10.21276/ujds.2021.7.1.13

Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. (2020). Surat

Edaran Direktur Jenderal Pendidikan Tinggi Republik

Indonesia Nomor 1 Tahun 2020 tentang Pencegahan

Penyebaran Corona Virus Disease ( Covid-19) di

Perguruan Tinggi. Kemendikbud.

Khan, M. A., Vivek, Nabi, M. K., Khojah, M., & Tahir, M.

(2020). Students’ perception towards e-learning during

COVID-19 pandemic in India: An empirical study.

Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(1), 1–14.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010057

Kimkong, H., & Koemhong, S. (2020). Online learning

during COVID-19: Key challenges and suggestions to

enhance effectiveness. Cambodian Education Forum

(CEF), December, 1–15.

Kuntarto, E. (2017). Keefektifan model pembelajaran

daring dalam perkuliahan Bahasa Indonesia di

perguruan tinggi. Indonesian Language Education and

Literature, 3(1), 99-110.

Lim, Ping, C., Wang, & Libing. (2016). Blanded learning

for quality higher education: Selected case studies

implementation from Asia-Pasific. UNESCO.

Martínez-Muñoz, D., Martí, J. V., & Yepes, V. (2021).

Remote teaching in construction engineering

management during COVID-19. INTED2021

Proceedings, 1(March), 879–887. https://doi.org/

10.21125/inted.2021.0205

ICPsyche 2021 - International Conference on Psychological Studies

226

Masoud, N., & Bohra, O. P. (2020). Challenges and

opportunities of distance learning during COVID-19 in

UAE. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies

Journal, 24(1), 1–12.

Moore, J. L., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyen, K. (2011). E-

Learning, online learning, and distance learning

environments: Are they the same? Internet and Higher

Education, 14(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.iheduc.2010.10.001

Oumar, B.S. Aziz, S.A., & Wok, S. (2021). The impact of

Emergency Remote Teaching and Learning ( ERTL )

during COVID-19 pandemic on students. Journal of

Communication Education, 1(1), 23-38.

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I.,

Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L.,

Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R.,

Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu,

M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E.,

Mcdonald, S., Mckenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020

explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and

exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ,

372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Parsazadeh, N., Megat, N., Zainuddin, M., Ali, R., &

Hematian, A. (2013). A review on the success factors

of e-learning. The Second International Conference on

E-Technologies and Networks for Development, 42–49.

Perveen, A. (2016). Synchronous and asynchronous e-

language learning: a case study of Virtual University of

Pakistan. Open Praxis, 8(1), 21–39.

https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.1.212

Puspandari, D. A., Zulaiha, R., & Hafidz, F. (2020). Online

learning during a pandemic. Proceedings of the

International Conference on Educational Assessment

and Policy (ICEAP 2020), 545(Iceap 2020), 196–199.

https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210423.087

Rafique, G. M., Mahmood, K., Warraich, N. F., & Rehman,

S. U. (2021). Readiness for online learning during

COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of Pakistani LIS

students. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(3),

102346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102346

Ramlogan, S., Raman, V., & Sweet, J. (2014). A

comparison of two forms of teaching instruction: Video

vs. live lecture for education in clinical periodontology.

European Journal of Dental Education, 18(1), 31–38.

https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12053

Rana, S., & Garbuja, K. (2021). Nursing students ’

perception of online learning amidst COVID-19

pandemic. Journal of Lumbini Medical College, 9(1),

1-6.

Sadikin, A., & Hamidah, A. (2020). Pembelajaran daring di

tengah wabah COVID-19. Biodik, 6(2), 109–119.

https://doi.org/10.22437/bio.v6i2.9759

Sulata, M. A., & Hakim, A. A. (2020). Gambaran

perkuliahan daring mahasiswa Ilmu Keolahragaan

Unesa di masa pandemi COVID-19.

Jurnal Kesehatan

Olahraga, 8, 147–156.

Turner, J.W., Wang, F. Reinsch, N.L. (2020). How to be

socially present when the class becomes “suddenly

distant” The Journal of Literacy and Technology

Special Issue for Suddenly Online – Considerations of

Theory, Research, and Practice, 21(2), 76-101.

Vanslambrouck, S., Zhu, C., Lombaerts, K., Philipsen, B.,

& Tondeur, J. (2018). Students’ motivation and

subjective task value of participating in online and

blended learning environments. Internet and Higher

Education, 36, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.iheduc.2017.09.002

Yahaya, M. F., Halim, Z.A., Sahrir, M.S., & Hamid, M.F.A.

(2021). Need analysis on developing arabic language

m- learning basic level during COVID-19. Journal of

Contemporary Issues in Business and Government,

27(2), 5452–5461. https://doi.org/10.47750/cibg.20

21.27.02.551

Yuliani, dkk. (2020). Pembelajaran daring untuk

pendidikan: Teori dan penerapan. Yayasan Kita

Menulis.

College Students Perspective on Online Learning during COVID-19: A Systematic Literature Review

227