Systematic Review on Cybersecurity Risks and Behaviours:

Methodological Approaches

Eliza Oliveira

a

and Vania Baldi

b

Digital Media and Interaction Research Centre, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords: Cybersecurity, Risk Perception, Precautionary Behaviour, Literature Review, NVivo.

Abstract: This paper presents a systematic literature review regarding risk perception and precautionary behaviour

related to cybersecurity. Objectives encompassed identifying issues related to methodological approaches, the

studies’ operationalisation and other essential topics, highlighting significant gaps to be fulfilled in future

investigations. The study included a search in the multidisciplinary databases of Science Direct, Web of

Science, and the Scientific Repositories of Open Access in Portugal, focusing on publications after 2016. A

total of nine articles were analysed. The review was developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols’ research method. Also, publications were coded using the

NVivo 12 software for synthesising the results. The small number of studies considered for analysis revealed

that risk perception and precautionary behaviour concerning cybersecurity is still an under-explored study

area. Furthermore, methodological gaps are highlighted for future works. Studies in the cybersecurity field

provide a dataset for policymakers, directing efforts and predicting responses to digital technologies, making

this subject matter highly substantial.

1 INTRODUCTION

Humanity has lived an era of extraordinary success

concerning digital technological advancements,

allowing the dissemination of information, and

enabling communication worldwide (Castells, 2011;

Pinto & Cardoso, 2021). Moreover, with the

progressive evolution of digital solutions and the

democratization of electronic devices, citizens use the

Internet anytime and anywhere they wish (Baldi &

Oliveira, 2018).

However, despite contributing to interpersonal

interaction and information transmission

effectiveness, the new paradigm in information

systems and communication processes has brought

security and privacy problems within the digital

environments (Conteh & Schmick, 2021).

In this context, data are frequently forged and

defrauded, making the digital environment a constant

threat to information-sharing security (Loon, 2003).

Examples of hazards that threaten the integrity of

personal data on the Internet include phishing,

doxing, identity thief, cyberbullying, viruses,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3518-3447

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7663-3328

surveillance and spyware (Conteh & Schmick, 2021).

Further, while everyone is exposed to several kinds of

danger, the use frequency of digital technologies

seems to be directly related to the increase of risk of

cyberattacks (Cheng, Lau, and Luk 2020).

According to Slovic (1981), the risk scenario

regarding the technologies involves the citizens’

awareness of the hazards they are exposed to. Thus,

the security of personal information is associated to

the user’s behaviour on the Internet, being Risk

Perception (RP) a predictor of the individuals’

precaution when facing risks (Assailly, 2010).

Risk perception is not a recent study area and has

been the subject of interest in different knowledge

domains, aiming to understand citizens perceptions

concerning the exposure to several hazards in society

(Slovic, 2000). Nevertheless, although a diversity of

hazards arises with the digital technologies, limited

attention has been given to RP and Precautionary

Behaviours (PB) in this area (Oliveira & Baldi, 2019).

In this paper, we update the prior work to deepen

understanding of how Risk perception and

Precautionary Behaviour regarding cybersecurity are

Oliveira, E. and Baldi, V.

Systematic Review on Cybersecur ity Risks and Behaviours: Methodological Approaches.

DOI: 10.5220/0010762600003197

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk (COMPLEXIS 2022), pages 49-56

ISBN: 978-989-758-565-4; ISSN: 2184-5034

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

49

currently being investigated (Oliveira & Baldi, 2019).

Therefore, we expand our search to 2021 to achieve

recent studies concerning these themes. In addition,

we adopted the structural methodology “PRISMA”

(Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews

and Meta-Analyses) and used the NVivo 12 software

for a systematic coding that gave rise to new

discussion topics compared to those analysed in the

previous study.

The article is organised as follows. In section two,

we present the background theory and relevant

studies. Subsequently, the methodology of this

systematic review is presented. Section 4 present the

results, and Section 5 the discussion. Finally, section

6 provides the most relevant conclusions.

2 BACKGROUND

There is no consensus in the literature regarding the

meaning of the word risk. While according to some

authors, the Latin etymology means that risk

separates us from the known to confront us with the

unknown and challenge it (Assailly, 2010; Bernstein,

1996), Mythen (2004) says that the derivations of the

term “risk” come from the Arabic word “risq”, related

to the acquisition of health and fortune. Moreover, the

risk is also related to “The actions we dare to take,

which depend on how free we are to make choices.”

(Bernstein, 1996, p. 29), introducing the subjectivity

of what is considered risky in different cultures.

Lash (2000) presents that dangers or risks, in the

risk culture, should not be understood as being

objective, but as inscribed in individualized ways of

life, defending, therefore, that the perception of risk

is an essential matter since it is subjective and is

intrinsically related to the contexts of each citizens’

lives. In this sense, Paul Slovic (2000) refers to Risk

Perception as an intuitive daily risk judgment that the

citizens rely on to evaluate typical and catastrophic

hazards. As an interdisciplinary subject of concern,

risk perception is not a recent area of knowledge

(Starr, 1969) and has been widely studied across

different fields, including psychology, social

sciences, geography and anthropology (Slovic, 2000).

Also, the past studies on risk perception have mainly

been carried out in the United States and

encompassed the proposal of a set of risk dimensions

that help identify behavioural patterns in hypothetical

situations related to the decision-making process

when facing risks (Slovic, 1981). Some of these

dimensions are the severity of consequences of the

hazard, catastrophically effect of the danger,

vulnerability face the danger, the novelty of the

hazard, and level of knowledge about the hazard.

Further, Slovics’ works were mainly directed to the

latest devices and technologies of the time, such as X-

ray, nuclear power, cars and parachutes (Slovic,

1981; 1990). Regarding the dangers associated to

digital technologies, some works are worth

mentioning. For instance, the literature shows that the

more voluntarily exposed people are to phishing, the

lower they perceived the risk of getting involved in

situations like these on the Internet. Also, the risk

perceived is reduced when positive effects are

immediate and negative consequences of an action

are delayed (Kahneman, 2011).

Huang (2010) and Garg & Camp (2012) studied

21 and 15 dangers related to the cybersecurity

domain, respectively. Higher perception of risk is

directly related to the severity of consequences of a

danger, duration of its impacts and previous accident

history involvement in the cybersecurity domain

(Huang, 2010). Equally, Garg & Camp (2012)

verified that voluntariness to danger, knowledge of

science concerning a hazard, controllability of the

danger, the newness of the danger, dread, and severity

of effects were significant predictors of risk

perception. Moreover, while people frequently

underestimate cybersecurity threats (LaRose, Rifon,

& Enbody, 2008), perceived risk is lower when

people think they control a particular cybersecurity

situation (Rhee, Ryu, and Kim, 2012).

Ng et al. (2009) verified that an individuals’

security behaviour is directly proportioned to their

risk perception regarding the specific danger, the

perception of the threat, and the effectiveness of their

capacity to solve the problem. Additionally, the

authors affirm that individuals should use specific

necessary actions to avoid security problems, such as

using strong passwords, frequently changing

passwords, and conducting regular backups.

Pattinson and Anderson (2005) presented risk

perception as a mediator in the relationship between

risk communication and risk-taking behaviour in

information security. Concerning security actions,

although college students are highly engaged in more

precautionary behaviour (for instance, using anti-

virus software), Öğütçü et al. (2016) identified that

the exposure to hazards was highest among this social

fringe. Furthermore, Mariani & Zappala (2014)

verified that self-competence was related to a positive

precautionary behaviour against attacks from a

computer virus, while Slovic, MacGregor & Kraus

(1987) affirm that the risk dimensions that predict

perceived risk are also possible predictors of

precautionary behaviour. Therefore, risk perception

and precautionary behaviour are associated.

COMPLEXIS 2022 - 7th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

50

In the following section, we will present the

methodological path to operationalising the present

systematic literature review.

3 METHODOLOGY

Systematic reviews have received credibility in the

social sciences since they offer consolidated and

unbiased information about a particular subject and is

associated with a starting inquisition (Liberati et al.,

2009; Gough et al., 2017). Thus, the primary

outcomes of this systematic review must answer the

following question: What empirical works are

available in the literature on risk perception and

precautionary behaviour regarding cybersecurity

issues, and what are the main significant gaps to be

fulfilled in future studies?

The present work was developed using the

PRISMA method, a guided protocol for a systematic

review to achieve reliable data. The PRISMA method

ensures that the systematic review is carefully

planned and explicitly documented, promoting

consistent results by the review team, accountability,

research integrity, and transparency of the completed

review (Liberati et al., 2009).

In this sense, the first step was to define the data

basis for searching the documents related to risk

perception and precautionary behaviour within the

cybersecurity domain. Considering that these subjects

run through different knowledge areas, we opted for

Web of Science and Science Direct data basis.

Furthermore, the search was also made in the

Scientific Repositories of Open Access in Portugal

(RCAAP) to find works carried out under the

Portuguese scope.

After choosing the data basis, the next step was to

determine the appropriate keywords, covering risk

perception, cybersecurity, and precautionary

behaviour. This study was carried out in May 2021

and was limited to peer-reviewed journal and

proceedings articles published from 2016 onwards

since a relevant review was published in 2015

(Quigley et al., 2015). Works that exhibit studies

related to RP or PB but not encompass the two

subjects were also accepted. However, it is worth

highlighting that all the works should approach

cybersecurity issues. Also, the works must be

published in English and present empirical studies.

The screening process comprised the exclusion of

duplicate documents. Then, after the titles and

abstracts were analysed, the articles that did not fit the

inclusion criteria were removed. Next, the papers

have been fully read for the selection of the

appropriate studies for this review. After, the

publications were read in full and coded using the

NVivo 12 software. The parameters for analysis

were: (1) methods for data collection, (2) country of

the study, (3) sample, (4) methodological approaches,

(5) inclusion of the topics in the query (i.e., RP, PB,

and Cybersecurity), (6) articles’ keywords, and (7)

cybersecurity issues addressed.

4 RESULTS

The categories in NVivo were aggregated into groups

that contain relevant topics for the analysis of results.

4.1 Overview of the Studies

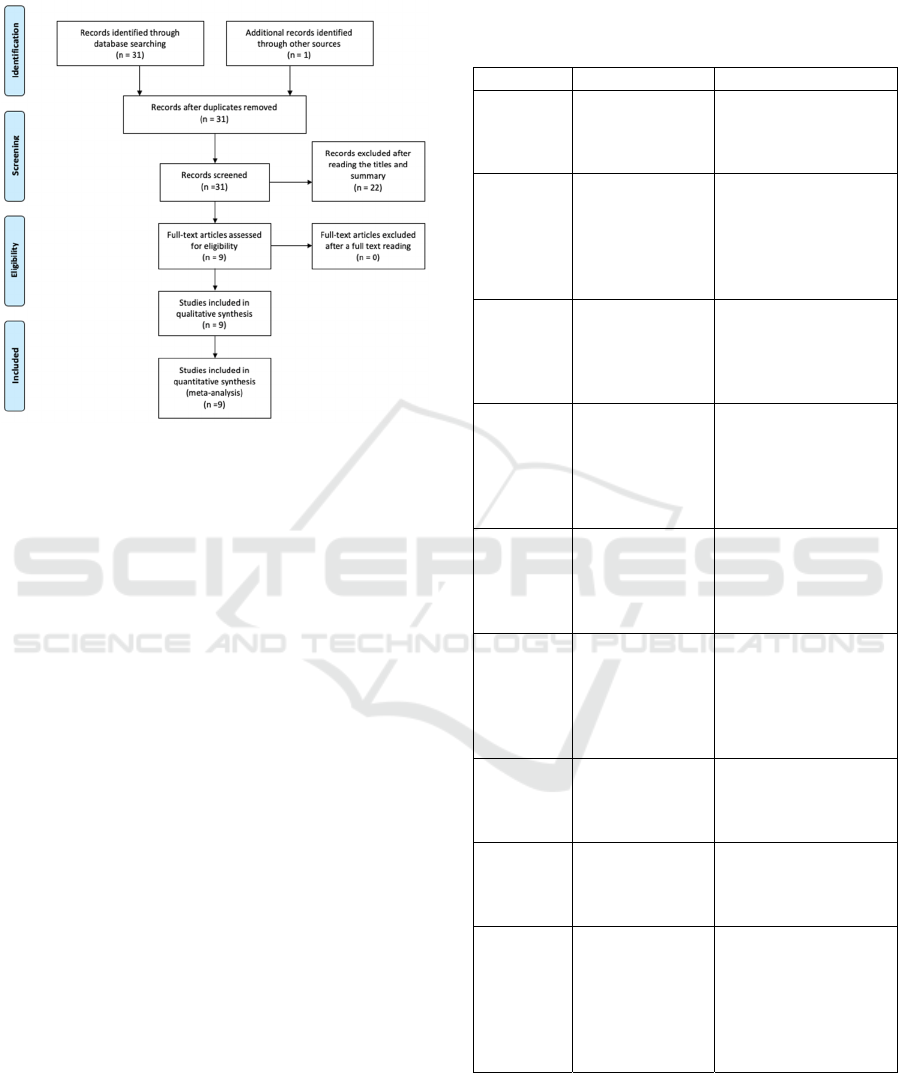

As a result of the search in the previously mentioned

databases, 30 articles were found in Science Direct,

only one repeated article has been found in Web of

Science, and none was found in the RCAAP.

Furthermore, an extra article has been integrated into

this study since it complies with the inclusion criteria.

Thus, 31 research articles were considered possible to

use in this systematic review, with only nine elected

at the end of the screening process. Figure 1 shows

the PRISMA flow diagram with the screening of the

articles to integrate this study.

The main regions where the studies were carried

out included the United Kingdom and the USA, with

five and three studies conducted in these countries,

respectively. Other countries were Netherlands,

Turkey, Hong Kong, Germain, Sweden, Poland and

Spain. Among the papers, only one was published in

2016, while two studies were published in 2017, two

in 2018, two in 2019, and two in 2020. Table 1

presents the general information of the studies, with a

list of the authors, year of publication, the goal of the

study, and the main contributions of the articles.

4.2 Methods and Methodologies

Concerning the methodological approaches, the

papers present quantitative approaches, comprising

experimental and empirical studies. Eight studies

conducted online surveys, while one used a telephone

survey to collect data (Cheng et al., 2020). In

addition, participants were chosen through different

methods, with seven papers using online recruitment,

one using the selection as a sample method (Öğütçü

et al., 2016), and one using the random digit dialling

method (Cheng et al., 2020). The digital recruitment

method encompassed Toluna (Bavel et al., 2019),

recruitments by e-mail (Schaik et al., 2017; Jeske et

al., 2017; Schaik et al., 2020), recruitment services of

Systematic Review on Cybersecurity Risks and Behaviours: Methodological Approaches

51

online panels (Jansen & Shaik, 2019; Shaik et al.,

2018), and Mechanical Turk (Cain et al., 2018).

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow diagram with the screening

process and number of documents selected in each phase.

Data were collected using a psychometric

paradigm with internet users through different scales

in all studies. In this direction, none of the research

articles presented a distinct strategy for obtaining

outcomes, all using a traditional rating scale as a

metric measure in the empirical phase.

4.3 Sample

The sample was different in all articles, comprising a

minimum of 201 in the work of Van Shaik et al.

(2018) and a maximum of 2014 in the empirical study

conducted by Bavel et al. (2019). The mean age in the

Bavel et al. (2019) studies was 40.8 years, with 50.3%

of females and 40.84% with upper secondary

education. Jansen & Schaik (2019) carried out two

studies (ages between 19-76 years), being one with

1,201 individuals (50.6% females and 52.4% with

high education), and a second with a sample of 768

individuals, being 51.4% men and 52.5% with high

education. In Cain et al. (2018), the age range of the

sample was between 18-55+ years, with 142 women

and 24.63% with higher education, against an average

age of 42 years in a sample of 201 Facebook users,

characterized by 92 women and 55% with less than

fist degree in the studies of Schaik et al. (2018). In the

work of Schaik et al. (2017), the mean age of the 436

participants was 23, with 336 females. Further, Jeske

et al. (2017) conducted a study with 323 participants

with a mean age equal to 22.78 in an age range from

18-60 (74.9% women), while the works of Öğütçü et

al. (2016) included a sample with the mean age of

28.1 years old with 70.4% with high students’ degree.

Table 1: General information of the studies.

Article Goal Main results

Schaik et

al. (2020)

Check

Facebook CS

issues.

Affect is positive for

perceived benefit and

negative of perceived

ris

k

Cheng et

al. (2020)

Verify IT use

and risk to

involve in CS

issues.

Cybercrime

victimization was

inversely associated

with perceived

control, fairness, and

happiness.

Bavel et

al. (2019)

Explore the

effects of

notifications on

CS behaviour.

Coping messages

were more effective

than threat appeals in

promoting secure

online behaviou

r

Jansen &

Schaik

(2019)

Examine the

impact of fear

appeal messages

on security

behaviours

against phishing

Fear appeals have

great potential to

promote cybersecurity

behaviour.

Cain et al.

(2018)

Explore the

users’ behaviour

regarding cyber

hygiene.

Gender and age are

determinants in users’

behaviour and

knowledge regarding

cyber hygiene.

Schaik et

al. (2018)

Examined risk

perception and

precautionary

behaviour

related to CS in

Faceboo

k

.

Perception of risk was

highest for

cyberbullying and

information sharing.

Schaik et

al. (2017)

Examined risk

perception and

precautionary

b

ehaviour in CS

Risk Perception was

higher for identity

thief, keylogger and

c

y

berbull

y

in

g

.

Jeske &

Schaik

(2017)

Examined the

familiarity of

users about 16

online threats.

Three clusters of

knowledge were

labelled regarding

securit

y

behaviour.

Ögütçü et

al. (2016)

Examined levels

of awareness

toward

information

security in terms

of perception

and behaviou

r

.

Results show

significant differences

within samples and

habits of internet

usage.

Schaik et al. (2020) presents two studies, one with

63 and the other with 233 individuals. The first

sample with a mean age of 51.19 and the second with

the mean age of 52.13, both ranged from 22 to 79,

COMPLEXIS 2022 - 7th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

52

while in Cheng et al. (2020), the average was 42.18

years old, with the range among 10-65. Finally, while

the major sample of analysis encompassed random

people from the population, the sample in Shaik et al.

(2017) and Jeske et al. (2017) were university

students, and Öğütçü et al. (2016) comprised people

associated with the university environment.

4.4 Topic Trends

With the word frequency NVivo functionality, the

keywords determined by the authors in the studies

were verified, highlighting the topic trends among

articles. It shows that “Information” and “Security”

are the most frequent words the articles use as a

keyword directly relating to cybersecurity. The words

“Risk” and “Perception” appear more often than

“Precautionary”, meaning that studies are more

related to risks than to precautionary factors.

Nevertheless, the “Behaviour” (or its analogue

“Behavior”) subject emerges, showing that studies

regarding users’ behaviour are a topic of concern.

It is worth highlighting that, although studies do

not always use concrete keywords, topics were

interpreted according to the nature of the variables

studied. Thus, even if a study does not use the term

Precautionary behaviour but uses Security behaviour,

it was considered that such works included an

analysis within the precautionary online behaviour

topic of concern. Simultaneously, if a specific work

measures the perception of digital hazards, the RP

was identified as a matter of study.

Furthermore, based on the text search and word

count on NVivo, it was possible to verify the most

online security hazards addressed by the articles. We

found that the words “cyber” and “attack” appear

more frequently among articles, reflecting a broad

topic with several threats. Among these threats are

viruses, phishing, and identity thief, which had the

second higher frequency in the articles, followed by

trojan, keylogger, cookies and rogue ware, which is a

less explored subject among the papers.

5 HINTS FOR FUTURE

RESEARCH

Intending to provide a satisfactory answer to the

research question, in this section, we provide a

discussion concerning the methodological

approaches and additional topics to present gaps to be

fulfilled in future works.

Three papers selected in this review used the

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) to fundament

their studies (Bavel et al., 2019; Jansen & Schaik,

2019; Schaik et al., 2020). The PMT attempts to

explain the cognitive processes that mediate

behaviour in the face of a threat, which may lead to

two different processes, including focusing on the

threat itself or the action against the threat (Rogers et

al., 1975). In this sense, studies of Bavel et al. (2019)

Jansen & Schaik (2019) conducted experiments with

participants, using copying and threat appeal

messages to identify security behaviour. Coping

messages were more effective than threat appeals in

promoting secure online behaviour in Bavel et al.

(2019) 's study, while, in contrast, fear appeals have

great potential to promote cybersecurity behaviour in

the works of Jansen & Schaik (2019). Schaik et al.

(2020) also found that "affection" is a positive

determinant of perceived benefit, indicating that a

risky online service could persuade someone to use

their products with an enticement strategy, increasing

the perceived benefit, leading to low perceived risk.

While these three works conducted experiments

with participants, the others had no intention to

intervene with individuals. This ups on new future

work possibilities, as intervention studies could bring

accurate information concerning precautionary

behaviour and gather knowledge of improving

peoples' awareness regarding digital technologies

(Kirlappos & Sasse, 2012).

Methodological limitations are observed as all the

works used psychometric measures to collect and

analyse data. Consequently, there is a lack of

qualitative data concerning risk perception and

precautionary behaviour in cybersecurity. This is

significant since precautionary behaviour and risk

perception are directly related to cultural factors and

social constructs (Mythen, 2004). In this sense, the

lack of qualitative measures and approaches makes it

difficult to gather subjective data regarding the

specific behaviour (Mishna et al., 2018).

To know in-depth about the nature and

characteristics of a given phenomenon and discover

the reasons for observed patterns, qualitative analyses

are necessary (Busetto, Wick, and Gumbinger, 2020).

Regarding cybersecurity, Mishna et al. (2018) state

that while quantitative analysis provides results that

can be generalised, qualitative analyses add rich

information that allows a deep understanding of cyber

aggression. Mythen (2004) presents a critique

regarding the frequent use of the psychometric

paradigm in research on risk perception by social

sciences, claiming that risk perception and security

behaviour are culturally and subjectively constructed.

Systematic Review on Cybersecurity Risks and Behaviours: Methodological Approaches

53

In this sense, RP and PB should also be analysed

through a qualitative lens, through a focus group or

interviews, which presents itself as a reliable manner

to achieve a rich understanding of the participant's

point of view (Mishna et al., 2018).

However, it is noteworthy that, to develop

comparable works, a methodological and conceptual

cohesion between academic research is necessary

(Oliveira & Baldi, 2019). In addition, inconsistencies

between definitions lead scholars to study different

phenomena under the same title, so it is essential to

reach a consensus on the definition and concept of the

studied phenomena (Olweus & Limber, 2018).

Therefore, an effort must be made to standardise the

concepts so that comparison between studies is

possible.

Since the entire world is changing its habits,

moving the daily activities from the physical world to

a digital one, substantial contributions can be

achieved by conducting a cross-cultural study. For

instance, Bavel et al. (2019) found that Polish and

Spanish individuals are the more insecure among

people from Sweden, Germany, and United

Kingdom. Also, interesting outcomes encompassed

the different security behaviours among people from

different nationalities, indicating that the decision-

making process changes across countries (Bavel et

al., 2019). In addition, Jeske et al. (2017) found

differences in the familiarity with cyber-threats

between people from the UK and the US, with the last

one presenting more informed about phishing and

social engineering. Similarly, Schaik et al. (2017)

showed that university students from the UK perceive

risks differently from the US. Thus, cross-cultural

studies can bring valuable information for creating

public policy cohesion in European countries.

Age is another topic of attention. Samples with a

wide range of ages are more likely to identify

disparities in people's behaviours in different age

groups, making it possible to compare opinions and

behaviours between several fringes. For example,

Ögütçü et al. (2016) found that college students seem

to be the most at-risk group, probably due to higher

intense and frequent use of the Internet, especially

social media. Bavel et al. (2019) affirm that age had a

significant impact on the probability of suffering a

cyberattack: "the older the participant, the more

securely he or she navigated through the mock

purchasing process." (p. 35). Also, their outcomes

suggest that older adults are more vulnerable than

younger adults to phishing attacks but less vulnerable

to other cyber threats. Furthermore, both younger and

older adults are likely to modify their security

behaviours when following a warning of some kind

(Bavel et al., 2019), although older adults tend to

generally behave more securely than younger users

on the Internet (Cain et al., 2018). This finding was

unexpected since younger people usually have higher

know-how about cybersecurity (Ögütçü et al., 2016).

Considering the importance of comparable data

across ages to implement more effective public and

contextual policies in different environments (e.g.,

universities, e-learning, social media, online

banking), the Governmental organisations, research

institutions, and the industry would benefit from

studies encompassing individuals' security behaviour

on Internet across several ages. However, studies that

focus on a restricted social fringe can introduce

specific and more profound knowledge regarding the

studied population, being also relevant.

Regarding the perception of risk, Schaik et al.

(2017; 2018) found that the hazards/activities judged

to be most risky on Facebook were cyberbullying and

failing to receive login notifications about the user.

Additionally, it was identified that cyberbullying had

elevated scores on general risk perception

measurement (Schaik et al., 2017). Hence,

considering that cyberbullying had the higher score

among other cyber threats, has been widely studied

and has a high prevalence in many countries

(European Parliament, 2016), future works should

involve online aggressions, such as cyber-

harassment, hate speech, and cyber-stalking, to verify

RP and PB regarding these threats.

The relevance of studying cybersecurity is related

to the damage caused by cyberattacks at a national

and international level (Cheng et al., 2020). Hallman

et al. (2020) present that the organisations and

citizens suffer each day more with cyberattacks,

giving rise to significant financial losses in several

countries. Cybersecurity is, therefore, becoming

critical to ensure the safety of humans and societies

(Omerovic et al., 2019). In this regard, studies in the

cybersecurity domain could help gather knowledge

concerning human behaviour on the Internet, which

helps to understand adequate security training under

a specific population or context. People trained in

cyber-hygiene or cybersecurity have higher

precautionary behaviours, indicating a good strategy

to prevent cyberattacks (Cain et al., 2018; Mishna et

al., 2018). In this sense, longitudinal works could be

helpful to verify the effectiveness of specific training

in the cybersecurity field (Jansen & Schaik, 2019).

Finally, it is suggested more studies on RP and PB in

cybersecurity domain, especially in the Portuguese

context, which must be deposited in national

databases to enrich nationalised scientific data.

COMPLEXIS 2022 - 7th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

54

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presents a systematic review of risk

perception and precautionary behaviour facing

cybersecurity threats. We expanded on prior work to

understand how Risk perception and Precautionary

Behaviour regarding cybersecurity are currently

being studied. To provide reliable answers to the

research question, it was realized with the PRISMA

method and NVivo software. Although risk

perception is a long-time study area, and a plethora of

threats frequently emerge, a small number of works

revealed that RP and PB regarding cybersecurity are

still under-explored.

The articles’ attention is on the security of

personal information, being other cyber-threats, such

as sexting, cyber-harassment and cyberbullying, not

frequently addressed. In this sense, future works

should encompass these topics in their surveys or

other measurement data collection. Furthermore,

studies with practical experiments are also

encouraged since they could bring accurate

information concerning precautionary behaviour,

elaborating practical training to better use the

Information and Communication Technologies.

Finally, in the current scenario, social networks offer

new opportunities for sociability (Pinto & Cardoso,

2021) and communication being, however, necessary

to pay attention to cybersecurity issues to promote

interaction in a safe digital environment. Therefore,

studies in RP and PB contribute to achieving insights

to produce more secure commercial products, such as

better protective software and hardware. Further,

studies in the RP and PB area provide relevant

information for policymakers to build efficient

preventive and coping strategies, helping to predict

public responses to technologies (Slovic, 1981;

Fischhoff et al., 1978), making the subject matter in

this review highly important.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Portuguese

Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT)

through the FCT fellowship 2020.04575.BD.

REFERENCES

Assailly, J.-P. (2010). The psychology of risk. Nova Science

Publisher, INC, New York.

Baldi, V., Oliveira, E. (2018). A queda do império

Facebook: uma análise sobre os motivos que levam ao

afastamento da rede social. Educación comunicación

mediada por las tecnologías. pp. 41–60. EGREGIUS

Ediciones, Sevilha.

Bavel, R. V., Rodríguez-Priego, N., Vila, J., Briggs, P.

(2019). Using protection motivation theory in the

design of nudges to improve online security behavior.

Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 123, 29–39.

Bernstein, P. (1996). Against-the-Gods-The-Remarkable-

Story-of-Risk. John Wiley & Sons, INC, New York.

Busetto, L., Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to

use and assess qualitative research methods.

Neurological Research and Practice, 2(1).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Cain, A. A., Edwards, M.E., Still, J.D. (2018). An

exploratory study of cyber hygiene behaviors and

knowledge. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 42, 36–45.

Castells, M. (2011). A Sociedade em Rede. A Era da

Informação: Economia, Sociedade e Cultura. 4ª ed.,

vol. 1. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa.

Cheng, C., Chan, L., Chau, C. (2020). Individual

differences in susceptibility to cybercrime victimization

and its psychological aftermath. J. Computer &

Security. 90, 1-16.

Cheng, C., Lau, Y. C., & Luk, J. W. (2020). Social Capital-

Accrual, Escape-From-Self, and Time-Displacement

Effects of Internet Use During the COVID-19 Stay-at-

Home Period: Prospective, Quantitative Survey

Study. Journal of medical Internet research, 22(12),

e22740. https://doi.org/10.2196/22740

Conteh, N. Y., & Schmick, P. J. (2021). Cybersecurity

Risks, Vulnerabilities, and Countermeasures to Prevent

Social Engineering Attacks. In N. Conteh (Ed.), Ethical

Hacking Techniques and Countermeasures for

Cybercrime Prevention. 19-31. IGI Global.

http://doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-6504-9.ch002

European Parlament. (2016). Cyberbullying among young

people.

Fischhoff, B., Slovic, P., Lichtenstein, S., Read, S., Combs,

B. (1978). How safe is safe enough? A psychometric

study of attitudes towards technological risks and

benefits. Policy Sci. 9, 127–152.

Garg, V., Camp, J. (2012) End User Perception of Online

Risk Under Uncertainty. In: Proceedings of 45th

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

3278– 87., Manoa.

Gough, D., Oliver, S., Thomas, J. (2017). An Introduction

to Systematic Reviews. SAGE Publications Inc,

London.

Hallman, R., Major, M., Romero-Mariona, J., Phipps, R.,

Romero, E. and Miguel, J. (2020). Return on

Cybersecurity Investment in Operational Technology

Systems: Quantifying the Value That Cybersecurity

Technologies Provide after Integration. Proceedings of

the 5th International Conference on Complexity, Future

Information Systems and Risk (COMPLEXIS 2020), 43-

52. DOI: 10.5220/0009416200430052

Huang, D.L., Rau, P.L.P., Salvendy, G. (2010). Perception

of information security. Behav. Inf. Technol. 29, 221–

232.

Systematic Review on Cybersecurity Risks and Behaviours: Methodological Approaches

55

Jansen, J., Van Schaik, P. (2019). The design and

evaluation of a theory-based intervention to promote

security behaviour against phishing. Int. J. Hum.

Comput. Stud. 123, 40–55.

Jeske, D., Schaik, P. Van. (2017). Familiarity with Internet

threat: Beyond a awareness. 66, 129– 141.

Kahneman, D. (2017) Thinking, Fast and Slow. Routledge,

New York.

Kirlappos, M.A. Sasse. (2012). Security education against

phishing: a modest proposal for a major rethink IEEE

Secur. Privacy, 24-32.

Lash, S. (2000). Risk Culture. In The Risk Society and

Beyond: Critical Issues for Social Theory (1st ed., 47–

63). Londres: SAGE Publications Inc.

LaRose, R., Rifon, N.J., Enbody, R. (2008). Promoting

personal responsibility for internet safety.

Communications of the ACM, 51 (3), 71-76,

10.1145/1325555.1325569

Liberati, A., Altman, D., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche,

P., Ioannidis, J., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P., Kleijnen, J.,

& Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for

reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of

studies that evaluate health care interventions:

Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Loon, J. Van. (2003). Risk and Technological Culture.

Towards a Sociology of Virulence. Routledge, London

and New York.

Mariani, M. G., Zappala, S. (2014). PC virus attacks in

small firms: Effects of risk perceptions and information

technology competence on preventive behaviors. TPM

- Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied

Psychology, 21(1), 51-65.

Mishna, F., Regehr, C., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Daciuk, J.,

Fearing, G., & Van Wert, M. (2018). Social Media,

cyber-aggression and student mental health on a

university campus. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3),

222-229. Doi:10.1080/09638237.2018.1437607

Mythen, G. (2004). A critical introduction into the risk

society. Pluto Press, Londres.

Ng, B.Y., Kankanhalli., Xu, Y. (2009). Studying users’

computer security behavior: A health belief

perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 46, 815–825.

Öğütçü, G. M. Testik, O. Chouseinoglou. (2016). Analysis

of personal information security behavior and

awareness Computers and Security, 56, 83-93,

10.1016/j.cose.2015.10.002

Olweus, D., Limber, S. P. (2018). Some problems with

cyberbullying research. Current Opinion in

Psychology, 19, 139-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

copsyc.2017.04.012

Oliveira & Baldi. (2019). Risk Perception and

Precautionary Behavior in Cyber-Security: Hints for

Future Researches. Proceedings of the Proceedings of

the Digital Privacy and Security Conference 2019. pp.

28-38.

Omerovic, A., Vefsnmo, H., Erdogan, G., Gjerde, O.,

Gramme, E. and Simonsen, S. A Feasibility Study of a

Method for Identification and Modelling of

Cybersecurity Risks in the Context of Smart Power

Grids. COMPLEXIS

Pattinson, M., Anderson. G. (2005). Risk communication,

risk perception and information security. Security

management, integrity, and internal control in

information systems. Springer

Pinto J., Cardoso T. (2021). Internet and Social Networks:

Reflecting on Contributions to Employability and

Social Inclusion. In: Martins N., Brandão D. (eds)

Advances in Design and Digital Communication.

Digicom 2020. Springer Series in Design and

Innovation, 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-

61671-7_38

Quigley, K., Burns., Stallard, K. (2015). Cyber Gurus:

rhetorical analysis of the language of cybersecurity

specialists and the implications for security policy and

critical infrastructure protection. Gov. Inf. Q. 32, 108–

117.

Rhee, H., Ryu, Y.U., & Kim, C. (2012). Unrealistic

optimism on information security anagement. Comput.

Secur., 31, 221-232.

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of

fear appeals and attitude change. J.

Psychol., 91 (1), 93-114.

Schaik, P. V., Jeske, D., Onibokun, J., Coventry, L., Jansen,

J., Kusev, P. (2017). Risk perceptions of cyber-security

and precautionary behaviour. Comput. Human Behav.

75, 547–559.

Schaik, P. V., Jansen, J., Onibokun, J., Camp, J., Kusev, P.

(2018). Security and privacy in online social

networking: Risk perceptions and precautionary

behaviour. Comput. Human Behav. 78, 283–297.

Schaik, P. V, Renaud, K., Wilson, C., Jansen, J., Onibokun,

J. (2020). Risk as affect: The affect heuristic in

cybersecurity. J. Computers in Human Behavior. 108,

1-10.

Slovic, P., Fischhoff, B., Lichtenstein, S., Roe, F.J.C.

(1981). Perceived Risk: Psychological Factors and

Social Implications. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng.

Sci. 376, 17–34.

Slovic, P., MacGregor, D., & Kraus, N. N. (1987).

Perception of risk from automobile safety defects.

Accident Analysis and Prevention, 19(5), 359-373.

Slovic, P. (1990). Perception of Risk: Reflections on the

Psychometric Paradigm. In: Krimsky and D. Golding

(ed.) Social Theories of Risk Westport. 117–52.

Praeger, New York.

Slovic, P. (2000). Perception of Risk. In: The Perception of

Risk. p. 511. Taylor & Francis Group; Routledge, Nova

York.

Starr, C. (1969). Social benefit versus technological risk.

What is our Society Willing to Pay for Safety. Science.

1232–1238.

COMPLEXIS 2022 - 7th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

56