An Agent-based Model Study on Subsidy Fraud in Technological

Transition

Hao Yang

1

, Xifeng Wu

1,

*

, Sijia Zhao

2

, Hatef Madani

3

, Jin Chen

4

and Yu Chen

1

1

SCS Lab, Department of Human and Engineered Environment, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences,

The University of Tokyo, Chiba 277-8563, Japan

2

Faculty of Economic and Management, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200062, China

3

Department of Energy Technology, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, SE-10044 Stockholm, Sweden

4

School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China

rochester2045@gmail.com, hatef.madani@energy.kth.se, chenjin@sem.tsinghua.edu.cn,

*

wuxifeng@edu.k.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Keywords: Agent-based Model, Technological Transition, Subsidy Fraud, Subsidy Policy, Socio Technical Transitions,

Complex System.

Abstract: The evolution of a society is inextricably linked to technological transition, which is based on both innovation

and dissemination of technologies. To protect the vulnerable new generation of technology, government

subsidies are one of the most common and effective tools. However, not all subsidy policies can lead to a

healthy development of market shares. Subsidy fraud is one of the most problematic issues that can arise

under an imperfect system. This paper identifies an interesting subsidy fraud like phenomenon via a validated

agent-based model. After analysing the mechanism of the transition of technology in the model, we drive the

condition upon which subsidy fraud could occur.

1 INTRODUCTION

Technological transitions are defined as a major

technological change in the way social functions

(e.g., transportation, communication, housing, food)

are achieved. For example, switching from

petroleum-fuelled cars to electrical vehicles, from

fossil-fuelled power stations to solar power stations

can both be regarded as technological transitions.

Innovation and dissemination of technology are very

important to the technological transition; hence the

promotion of innovation and the clarification of the

diffusion mechanism are the core goals pursued by

modern management science.

One of the most common and effective means of

helping the spread of new technologies is the use of

government subsidies. In particular, the government

provides subsidies through direct methods such as

price reductions or exemptions for companies or

consumers that use new technologies, or indirect

forms such as tax incentives. To a certain extent,

subsidies can compensate for the losses caused by the

immature new technology and stimulate companies

or consumers to use the new technology, thereby

*

Correspondence

helping to promote technological improvement and

increase the success rate of the realization of socio-

technological change.

However, in the actual implementation process of

government subsidies, many problems can arise. The

most met problem is subsidy fraud, which refers to

phenomena that individuals or firms provide incorrect

information when applying for government subsidies

or use subsidies in violation of the proposed intent

and agreement

1-2

. More specifically, there are

subsidies for different new energy sources in the low-

carbon transition process, while the government

promotes the diffusion of technologies through

advocacy (as in the case of the policy tools spreader

and subsidy introduced in Section 2.1.6 of the

methodology). Unfortunately, there is a gap between

actual policy effects and expectations, and when

social resources and policies are jointly focused on

specific things (e.g., low-carbon transition), it is

naturally very easy for the phenomena such as

subsidy fraud to arise under the influence of different

policy dissemination efforts (e.g., spreader) and

policy support efforts (e.g., subsidy). However, what

is the mechanism of subsidy fraud?

Yang, H., Wu, X., Zhao, S., Madani, H., Chen, J. and Chen, Y.

An Agent-based Model Study on Subsidy Fraud in Technological Transition.

DOI: 10.5220/0010887300003116

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2022) - Volume 1, pages 353-358

ISBN: 978-989-758-547-0; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

353

Analysing the mechanism of subsidy fraud and

proposing solutions are particularly important to the

government's subsidy policy. This article tries to

analyse the mechanism of subsidy fraud through the

mathematical analysis of a validated agent-based

model.

3-10

2 MODEL

This work is based on a baseline model of A.Lopolito

11

. Main parameters are set as the same value in the

original study (refer to Appendix. Parameter setting).

2.1 Model Descriptions

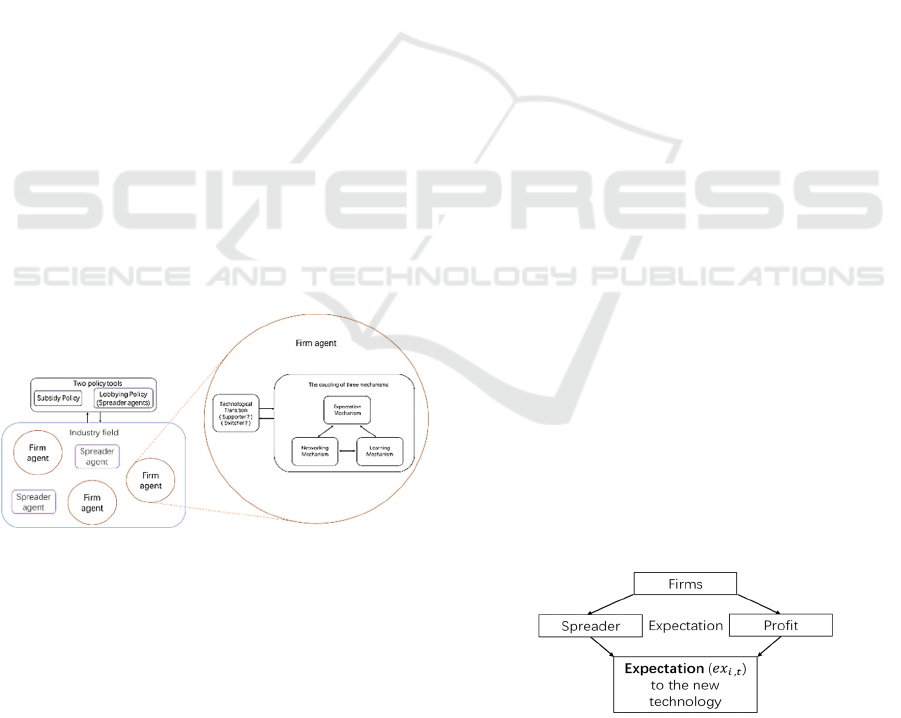

The conceptual framework of the model is shown on

Fig 1. There are many firm agents and few spreader

agents (responsible for spreading the new

technology). Each firm agent’s behaviour is guided

by three mechanisms: expectation, networking, and

learning. They determine whether a firm agent should

convert to a supporter or a switcher to the new

technology, thus collectively determining the state of

technological transition. There are also two policy

tools: the subsidy policy controls the size of the

subsidy; and the lobbying policy controls the number

of spreader agents.

For the assumptions and mechanisms in the model

and the significance of each parameter, we drew from

the literature11.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of the agent-based model

for technological transition.

2.1.1 Basic Assumption

As the basic assumption, the model assumes that there

are two technologies in the market, the new

technology and the old (traditional) technology. All

firms can freely choose one of the technologies to

produce goods in the next round. As the production is

completed, firms can further freely choose whether to

switch to a different technology or continue to use the

same technology.

The model consists of a finite number of firm

agents, 𝐼=1,2,⋯,𝑁

,𝑁

≪∞. It assumes that

all firms produce the same goods, and the market is

in the perfect competition state. Hence for all firms

that use traditional technology, their extra profit equal

to zero,

𝛱

,

=𝑅

,

−𝐶

,

=0 (1)

where 𝛱

,

, 𝑅

,

and 𝐶

,

represent the profit,

revenue and cost associated with the production at

time 𝑡 of firm 𝑖 which uses traditional technology.

As for firms using the new technology, risks and

profits coexist. These firms have an opportunity to

obtain extra profits, in the meantime, because the new

technology is often imperfect, they may suffer the

losses caused by unknown risks:

𝛱

,

=

𝑅

−𝐶

,

𝑤𝑖𝑡ℎ 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑏𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑝

0.5𝑅

−𝐶

,

𝑤𝑖𝑡ℎ 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑏𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦 1 − 𝑝

(2)

where 𝑝 stands for the probability that the firm

will obtain the maximum profit by using the new

technology.

2.1.2 Expectation Mechanism

The basic structure of the expectation mechanism is

shown in Fig 2. Parameter 𝑒𝑥

,

represents the

expectation to the new technology of firm 𝑖 at time 𝑡,

which is affected by the following two ways:

(1) By the profit by using the new technology

𝑒𝑥

,

=𝑒𝑥

,

+𝛱

,

(3)

(2) By the encounter with a spreader of the new

technology

𝑒𝑥

,

=𝑒𝑥

,

+𝜂 (4)

Figure 2: Expectation mechanism affected by the profit

from the new technology or by the encounter with spreaders

of the new technology.

ICAART 2022 - 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

354

2.1.3 Networking Mechanism

The basic structure of the networking mechanism is

shown in Fig 3. It mainly has the following two

functions.

Figure 3: Networking mechanism affected by the so-called

individual power and its sum over the whole network.

I. The formation of a user network of the new

technology

In our model, all the firm agents interact with each

other in a social space. We divide the distribution

space into several patches. Firms residing in the same

patch have closer social proximity. The formation

process of the network is shown in Fig 4.

(1) To establish a tie between firm 𝑖 and firm 𝑗 , the

following conditions need to be satisfied

1) Both firm 𝑖 and 𝑗 are supporters of the new

technology

2) The Social proximity between firm 𝑖 and 𝑗 is

less than the threshold value

(2) If a firm is no longer a supporter of the new

technology, all the ties from this firm will

disappear simultaneously.

Figure 4: The formation of a user network for the new

technology.

II. The reduction of cost for the new technology

We call all the shareable strategic resources

(except knowledge) individual power. The cost of a

firm agent using the new technology for production is

affected by two factors: the individual power (𝐼

,

)

of this firm, and the sum of individual power of all

firms in the network (𝑁

).

𝐶

,

=𝐶

,

−𝑐∙𝐼

,

−𝑛∙𝑁

(5)

where 𝑐 and 𝑛 are coefficients that adjust the

effectiveness of individual power of a firm and that of

the whole network. The individual power is further

affected by the profits:

𝐼

,

=𝐼

,

+𝛱

,

(6)

𝐸𝑛

,

=

𝐼

,

+𝐼

,

𝑖𝑓 𝑖 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑗 𝑎𝑟𝑒 𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑘𝑒𝑑

0 𝑖𝑓 𝑖 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑗 𝑎𝑟𝑒 𝑛𝑜𝑡 𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑘𝑒𝑑

(7)

𝑁

=

∑

𝐸𝑛

,

,

(8)

2.1.4 Learning Mechanism

The basic structure of the learning mechanism is

shown in Fig 5, which is similar to the networking

mechanism.

When a firm uses new technology to produce, it

may succeed and obtain positive profits, or it may fail

and get losses. Learning mechanism affects the

failure rate through the knowledge owned by all the

firms in the network.

(1) Knowledge (𝐾

,

)

𝐾

,

=𝑟𝑎𝑛𝑑𝑜𝑚

𝐾

,

=𝐾

,

+𝜃𝐾

,

(9)

(2) Knowledge network structure

1) 𝐾𝑓

,

=

𝐾

,

+𝐾

,

𝑖𝑓 𝑖 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑗 𝑎𝑟𝑒 𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑘𝑒𝑑

0 𝑖𝑓 𝑖 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑗 𝑎𝑟𝑒 𝑛𝑜𝑡 𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑘𝑒𝑑

(10)

2) 𝑁𝐾𝑛

=

∑

𝐾𝑓

,

,

(11)

(3) The decay of new technology failure rate

𝑅𝑠𝑘

=𝑅𝑠𝑘

−𝜀∙𝑁𝐾𝑛

(12)

where 𝑁𝐾𝑛

represents the network knowledge at

time 𝑡, 𝑅𝑠𝑘

represents the failure rate of using new

technology to produce.

Figure 5: Learning mechanism.

An Agent-based Model Study on Subsidy Fraud in Technological Transition

355

2.1.5 Technological Transition

Firms become supporters of the new technology,

when 𝑒𝑥

,

exceeds a critical value. Firms that use the

new technology are called switchers. A firm can

become a switcher only if the expected profit of the

new technology is positive, 𝐸𝛱

,

>0. Details can

be found in the following items.

(1) Conditions for becoming a supporter (𝑒𝑥

,

)

𝑓𝑖𝑟𝑚 𝑖

𝑎𝑡 𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑒 𝑡

→

𝑒𝑥

,

>0.75→ 𝑠𝑢𝑝𝑝𝑜𝑟𝑡𝑒𝑟

𝑒𝑥

,

≤0.75→𝑛𝑜𝑡 𝑠𝑢𝑝𝑝𝑜𝑟𝑡𝑒𝑟

(13)

(2) Conditions for becoming a switcher (𝐸𝛱

,

)

𝑓𝑖𝑟𝑚 𝑖

𝑎𝑡 𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑒 𝑡

→

𝐸𝛱

,

≤0→

𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑎𝑙

𝑡𝑒𝑐ℎ𝑛𝑜𝑙𝑜𝑔𝑦

→

𝑛𝑜𝑡

𝑠𝑤𝑖𝑡𝑐ℎ𝑒𝑟

𝐸𝛱

,

>0→

𝑛𝑒𝑤

𝑡𝑒𝑐ℎ𝑛𝑜𝑙𝑜𝑔𝑦

→𝑠𝑤𝑖𝑡𝑐ℎ𝑒𝑟

(14)

where the expectation profit to the new

technology can be calculated by the flowing equation:

𝐸𝛱

,

=𝐸

𝑅

−𝐸𝐶

,

=𝑒𝑥

,

∙𝑅

−

1

𝑒𝑥

,

∙𝐶

,

(15)

2.1.6 Policy Tools

Two policy tools are considered in this model: the

subsidy policy and the lobbying policy.

(1) Subsidy Policy

This policy is realized by adjusting the size of the

subsidy to cause an impact on the market.

After introduced the subsidy policy, the profit for

each agent changes as follows:

𝛱

,

=𝛱

,

+𝑠𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑖𝑑𝑦 (16)

(2) Lobbying Policy

This policy mainly affects the market by adjusting the

number of spreader agents. Spreader agents do not

participate in the actual production of goods, on the

other hand, they are effective in the market through

the expectation mechanism. They will automatically

find firm agents that do not have high expectations for

the new technology. By lobbying these firm agents,

spreaders can increase firms’ expectations for the new

technology 𝑒𝑥

,

, hence promoting the spread of the

new technology.

(3) Lobbying Policy

This policy mainly affects the market by adjusting the

number of spreader agents. Spreader agents do not

participate in the actual production of goods, on the

other hand, they are effective in the market through

the expectation mechanism. They will automatically

find firm agents that do not have high expectations for

the new technology. By lobbying these firm agents,

spreaders can increase firms’ expectations for the new

technology 𝑒𝑥

,

, hence promoting the spread of the

new technology.

3 RESULTS

The model implementing is based on Netlogo

platform. A population of N = 100 firms located on a

grid sized 32×32,and the model includes spreader

agents randomly moving within the social space to

inform those firms that have not yet adopted the niche

technology.

The parameterisation used is summarised in Table

1.

3.1 The Critical Condition

In the case of 𝑆𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑖𝑑𝑦=0, we can derive:

𝐸𝛱

,

=𝑒𝑥

,

∙𝑅

−

1

𝑒𝑥

,

∙𝐶

,

>0 ⇔ 𝑒𝑥

,

>

𝐶

,

𝑅

(17)

Combined with the initial conditions 𝑅

=

1.5 ,𝐶

,

=1, we can deduce the condition for

firms to become switcher without the subsidy:

𝐸𝛱

,

>0 ⇔ 𝑒𝑥

,

>

.

≈0.816 (18)

Since the condition for firm 𝑖 to become a

supporter has been set as 𝑒𝑥

,

≥0.75, clearly the

prerequisite for becoming a switcher is “being a

supporter”, which is also an intuitively plausible

ICAART 2022 - 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

356

scenario. If the firm does not support a technology, it

is almost impossible for it to use it.

However, due to the introduction of a subsidy, the

structure of Eq. (17) has been changed into the

following:

𝐸𝛱

,

=𝑒𝑥

,

∙𝑅

−

1

𝑒𝑥

,

∙𝐶

,

+𝑆𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑖𝑑𝑦>0

(19)

Hence a special case emerges: the condition to

become a switcher can be weaker than the condition

to become a supporter. From Eq. (19), we may

calculate that the critical size of the subsidy is 20.8%.

When 𝑆𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑖𝑑𝑦≤20.8%, the condition to become a

switcher is stronger than the condition to become a

supporter. In other words, the prerequisite for

becoming a switcher is to become a supporter. But

when 𝑆𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑖𝑑𝑦>20.8%, the situation will change,

and the prerequisite is no longer necessary. Because

the government subsidies are too strong, many firms

are willing to try to use new technology for

production even if they have not yet become

supporters of it. In such a scenario, many firms try out

the new technology, not because they are optimistic

about the technology, just because they are interested

in the large number of subsidies. Even though these

firms are willing to use niche technology for the

production activities, they do not make any efforts,

such as conducting the experiments or accessing the

supporter network, to develop the new technology.

3.2 Numerical Experiments

Even if the same parameter settings are used, the

model is still affected by random factors. To obtain

meaningful results, we average the outputs of 100

experiments, each of which contains 2600 timesteps

and is under the same initial conditions.

Through these numerical experiments, we found

that when the subsidy rate is higher than 20.8%, both

numbers of supporters and switchers quickly increase

to 100%. But if we cancel the subsidy, the entire

market reverses instantly. Although the number of

supporters can remain above 80%, the number of

switchers instantly becomes single digits, see the top

panel of Fig. 6. This result means that the entire

market is in an abnormally unhealthy state under the

too high subsidy: Firms use the new technology just

for the subsidies; when the subsidy is cancelled, those

firms who are not the real supporters of the new

technology leave the market instantly. Indeed, the

state after the cancellation of subsidy is consistent

with the stable state developed from the beginning

without the subsidy. This means that government

subsidies are completely ineffective. It is a

completely failed policy because the government has

spent huge amounts of money, but they did not reach

the goal of promoting the new technology.

Figure 6: Critical value experiment

(0 - 1500 timesteps: Subsidy = 21%, Spreader = 1.

1500 - 2600 timesteps: Subsidy = 0, Spreader = 1).

4 CONCLUSIONS

Government subsidies are an important factor to help

niche technology grow in the early stage of

technological development. By compensating for the

lack of profitability of technology, it can increase the

expected benefits of firms who have adopted the new

technologies and attract more firms to complete the

technological transition. However, due to regulatory

loopholes and other reasons, companies that only

hope to be decorated with the concept of new

technology or just want to defraud subsidies will

consume many social resources. Moreover, the fake

illusion of prosperity of the new technologies will

present an illusion to the industry and the

government. Once the sign of bubble collapse

emerges, these companies often get out fast causing

chaos in the corresponding industrial field. Therefore,

this article hopes to find the critical condition under

which firms may commit subsidy fraud.

Currently, we have obtained interesting

preliminary results and phenomena. At the same time,

as illustrated in the introduction section, we find that

An Agent-based Model Study on Subsidy Fraud in Technological Transition

357

subsidy fraud is prevalent in the low-carbon transition

process, which will help future validation studies of

the model. In addition, more rigorous and nuanced

studies, such as the assumptions adopted by the model,

need further refinement.

In the future, we also would like to further explore

how to systematically avoid the risk of subsidy fraud

and find a way to set up subsidy policies so that the

development of new technologies can be sustained

after the withdrawal of subsidies.

REFERENCES

Økokrim, Annual Report 2007, Norwegian national

authority for investigation and prosecution of economic

and environmental crime, Oslo, (2008).

Gottschalk, Petter. Categories of financial crime. Journal of

financial crime (2010).

Lopolito, Antonio, Piergiuseppe Morone, and Roberta

Sisto. Innovation niches and socio-technical transition:

A case study of bio-refinery production. Futures 43.1

(2011): 27-38.

Morone, Piergiuseppe, and Antonio Lopolito. Socio-

technical transition pathways and social networks: a

toolkit for empirical innovation studies. Economics

Bulletin 30.4 (2010): 2720-2731.

Lopolito, Antonio, Piergiuseppe Morone, and Richard

Taylor. An agent-based model approach to innovation

niche creation in socio-technical transition pathways.

Economics Bulletin 31.2 (2011): 1780-1792.

Victor, D., Geels, F. and Sharpe, S. Accelerating the low

carbon transition the case for stronger, more targeted

and coordinated international action. (2019). [online]

Available at: http://www.energy-transitions.org/

sites/default/files/Accelerating-The-

Transitions_Report.pdf [Accessed 21 Jan. 2020].

IPCC I. Working group III contribution to the fifth

assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on

climate change. (2014).

Geels F W. Technological transitions as evolutionary

reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and

a case-study. Research policy, 2002, 31(8-9): 1257-

1274.

Wu X, Xu Y, Lou Y, et al. Low carbon transition in a

distributed energy system regulated by localized energy

markets. Energy policy, 122 (2018): 474-485.

Sun, Y. A study on crisis in an agent-based socio-economic

system. Doctor. Tokyo University. (2018).

Lopolito, Antonio, Piergiuseppe Morone, and Richard

Taylor. Emerging innovation niches: An agent-based

model. Research Policy 42.6-7 (2013): 1225-1238.

APPENDIX

Table 1: Parameter setting.

Type Denotation Valuation Type Denotation Valuation

𝐺𝑙𝑜𝑏𝑎𝑙

𝑁

100

𝐺𝑙𝑜𝑏𝑎𝑙

𝑝

0.5

𝑁

1

𝑅𝑠𝑘

1−𝑝

𝑁𝐸

0.75

𝑒𝑥𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑛𝑎𝑙𝑃

0

𝜂

0.02

𝑅𝑎𝑑𝑖𝑢𝑠

1

√

𝜋

𝜋

0.001

𝐶𝑒𝑥

0.5

𝑛

0.01

𝐹𝑖𝑟𝑚 𝑖

𝑒𝑥

,

0.5

𝑐

0.01

𝐼

,

[0, 0.3]

𝜃

0.025

𝐾

,

[0, 0.01]

𝜐

2

𝐶𝑛

,

0.5

𝑆𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑖𝑑𝑦

0

𝐸𝛱

,

(15)

𝑅

1.5

𝛱

,

,𝛱

,

(1), (2)

𝑁

(8)

𝐿𝑖𝑛𝑘 𝑖,𝑗

𝐸𝑛

,

(7)

𝑁𝐾𝑛

(11)

𝐾𝑓

,

(10)

ICAART 2022 - 14th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

358