Is Ignorance a Bliss in Sustainability?

Evaluating the Perceptions of Logistics Companies’ Self-Assessment

in Environmental Performance

Oskari Lähdeaho and Jyri Vilko

LUT University, Tykkitie 1, Kouvola, Finland

Keywords: Logistics, Environmental Sustainability, Performance Measurement, Case Study.

Abstract: Effective management of any company relies on awareness of surroundings and ability to appropriately

measure and control the operations. As sustainability issues have emerged as central concern in societies,

companies are also aiming to improve their performance in this regard. Therefore, sustainability related

measurements are required for companies looking to manage their sustainability. Qualitative multiple case

study data reveals some inconsistencies between companies’ environmental performance and associated self-

evaluation and reporting. The case studies are analyzed with focus on management capabilities in informed

environmental sustainability related decision-making. It seems that companies are eager to take first steps

towards environmental sustainability. However, overconfidence from initial successes can hinder further

advances in environmental sustainability. Cognitive capabilities in self-evaluation seem to have implications

for organizations in addition to individuals. While vital for advances in environmental sustainability,

improvements should be reflected with critical view to avoid false sense of security. Companies’

environmental communications are often overexaggerated due to illusory superiority. Self-awareness in

context of companies’ environmental performance should be further studied.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sustainability of business operations is a growing

concern within societies, industries, and academia.

Companies carry special responsibility in

sustainability challenges, as their decision-making

often impact not only their own operations, but

surrounding environment and various external

stakeholders. Logistics and supply chain management

have extended influence towards environmental

sustainability due to the high environmental impact of

transportation (Solaymani, 2019). Therefore, supply

chain management is facing pressure towards

sustainability from governmental legislation as well

as societal demand (Seuring and Müller, 2008). In

European Union, transportation is subject to massive

decarbonization targets (European Commission,

2021; Haas and Sander, 2020). Moreover, in Finland

these targets are taken further from the baseline

legislation provided by European Union (Finnish

Government, 2020).

Informed decision-making in supply chain

management requires adequate knowledge, which in

turn stems from correct measurements and analytical

tools (Vilko et al., 2014). Same holds for decisions

and optimization towards more sustainable

transportation systems (Kelle et al., 2019). In other

words, for companies to acquire environmental

awareness of their operations, they need to recognize

the challenges and their own shortcomings in that

context. Thereafter, it is possible to understand

causalities related to sustainability related decisions.

This impact of their operations must be then

appropriately measured to allow management of

sustainability through various control mechanisms.

The aim of this paper is to study companies’

ability to self-evaluate their environmental

performance, and how their knowledge and

capabilities influence these assessments and affect

their decision-making. The chosen research area is

logistics industry, which faces pressure to increase its

environmental sustainability. The research focuses on

impact of cognitive biases, management knowledge

and capabilities, and decision-making uncertainty in

self-assessment of companies. By doing this, the

244

Lähdeaho, O. and Vilko, J.

Is Ignorance a Bliss in Sustainability? Evaluating the Perceptions of Logistics Companies’ Self-Assessment in Environmental Performance.

DOI: 10.5220/0010907200003117

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES 2022), pages 244-250

ISBN: 978-989-758-548-7; ISSN: 2184-4372

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

article instigates discussion on environmental self-

awareness of logistics industry actors.

2 METHODOLOGY

This research employs qualitative multiple case study

approach. The chosen method was used to create

holistic view on the studied logistics industry,

including different actors in the industry with varying

roles, position in network, transport modes,

ambitions, and maturity regarding environmental

performance. Moreover, specific company level

perspectives are attainable via case studies, which

allows critical evaluation of larger company

networks. Qualitative approach enables explorative

lens on the complex issue of sustainability in

logistics, which is required to study the characteristics

and inner-workings of a multimodal-transportation

networks.

Primary data gathering was carried out with semi-

structured interviews. This method was seen

appropriate to preserve the exploratory nature of the

research. Informants for the interviews were chosen

based on their experience and their organization’s

position in Finnish logistics system. In addition to

transportation companies and logistics service

providers (LSPs), infrastructure and regional logistics

developers were included in the pool of informants to

gain perspectives from higher level logistics

planning. Described selection process resulted in

twelve interviewees, as presented in Table 1. The

semi-structured interviews followed predefined

interview protocol with main themes related to

interviewee company’s technological, business, and

system level maturity regarding environmental

sustainability of their operations. However, the

interview protocol was used lightly, and the

interviewees were given the liberty to somewhat steer

the discussion. This way, relevant information and

themes that were not strictly determined in the

protocol were able to emerge in the interviews. In

addition to open ended questions on environmental

sustainability, the interviewees were also asked to

grade their companies’, as well as their network

partners’ perceived importance of environmental

sustainability. Grading was on Likert scale from 1 to

5, where 1 stands for “not important”, while 5 is for

“extremely important”. Since some of the companies

were not comfortable on grading with whole

numbers, they were given the chance to use fractional

numbers (e.g., 3.5 out of 5). Each interview took from

45 minutes to 1 hour.

The interviews were recorded and then

transcribed. Transcribed records were coded to

identify central topics in the interview data.

Table 1: Overview of the studied organizations.

Case or

g

anization Informant’s

p

osition in the com

p

an

y

Ex

p

erience in the current

p

osition

Railroad operato

r

Key Account Manage

r

11 years

Terminal operato

r

Sales directo

r

2 years

Transportation LSP Chief Development Office

r

5 years

LSP (4PL) CEO 9 years

Regional development company Sales manage

r

2 years

Logistics development company Project manage

r

1 yea

r

Transport infrastructure agency (road) Development manage

r

8 years

Regional logistics association Acting manage

r

7 years

Inland waterway infrastructure agency Regional manage

r

15 years

Shipping and stevedoring company Internal audito

r

2 years

Passenger road transportation company CEO 10 years

Regional passenger logistics planne

r

Public transport coordinato

r

3 years

Is Ignorance a Bliss in Sustainability? Evaluating the Perceptions of Logistics Companies’ Self-Assessment in Environmental Performance

245

To study companies’ ability in measuring and

evaluating their environmental performance, unit of

analysis for this study is the companies’ own

environmental sustainability. Based on this,

comparative company analysis is made with regards

to differences in the studied companies’ used

transport modes, role in logistics network, and

maturity of environmental sustainability in their

operations. Moreover, the interplay between these

companies in common networks must be considered.

3 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND AND

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Among individual people, cognitive bias can be

found where individuals with lower capabilities tend

to self-evaluate that skill higher, in contrary to skilled

individuals being more modest and accurate in the

evaluation (Dunning, 2011; Feld et al., 2017).

Because organizations consist of individuals, similar

bias can sometimes be found in companies (e.g., in

external communications or reporting). As the

amount of information is constantly growing

intensively, companies struggle to use the tide of

information in meaningful ways (Ge and Brewster,

2016). Moreover, mere existence of vast amount of

gathered information on specific topic (e.g.,

environmental sustainability) can falsely convince

companies that the information is properly used to

solve and manage the related challenges (Ge and

Brewster, 2016). In construction project cost

estimations, overconfidence on lacking capabilities

acts as one of the factors for possible cost overruns

(Ahiaga-Dagbui and Simon, 2014).

Environmental awareness and ability to make

informed decisions towards improved environmental

sustainability can be attributed to the management’s

ability in measuring environmental sustainability of

operations. Drawing from theoretical framework on

risk management and decision-making by Vilko et al.

(2014), we have synthesized a framework describing

different levels of environmental awareness and its

effect to sustainability related decision-making in

companies. The framework in question have not been

used in environmental context before, which this

study aims to do. In progress the research aims to

bring decision-making and environmental

management theories in logistics closer together. In

other words, this study synthesizes theories from

different fields of science to examine a contemporary

phenomenon. This framework is presented in Table

2.

The different columns in this framework represent

various levels of understanding or certainty related to

sustainability issues in supply chain management. On

the right side is radical uncertainty (hypothetical

situation where management has absolutely no

knowledge on the topic; Loasby,1976). From there

on, the consciousness of management increases

gradually going to left, ending up to absolute certainty

(once again, hypothetical situation where

management knows everything related to the topic) .

Table 2: Levels of uncertainty in sustainability decision-making (modified from Vilko et al., 2014).

Absolute certaint

y

Parametric certaint

y

Parametric

uncertaint

y

Structural

uncertaint

y

Procedural

uncertaint

y

Radical uncertaint

y

The knowledge deci-

sion-maker holds re-

lated to the decision

problem

Every piece of

relevant knowledge is

known.

The future states and the

structure of the decision

situation are known.

Impact of each

sustainability action is

objectively known.

The structure of future

is known. The impact

parameters of

sustainability actions

are not certain.

Imperfect knowledge of

the structure the future

can take. Limited view

of the parameters related

to the sustainability

actions.

Limitations of decision-

maker’s cognitive

abilities to

unambiguously pursue

objectives given the

available information.

All pieces of

knowledge are

imperfect, sometimes

even comes close to

ignorance.

The knowledge of the

occurrence

probabilities of

possible states of the

world, possible

actions, and

conse

q

uences

Complete knowledge. Objective knowledge of

parameters.

Subjective degrees of

beliefs as to the

probabilities of events

and the consequences

of sustainability

actions.

Subjective beliefs of the

effect of environmental

actions.

Incomplete knowledge

about effect of

environmental actions.

No knowledge at all.

Implications to

sustainability decision-

making

Complete certainty

about the

sustainability actions

and environmental

effects.

(Hypothetical)

Assumed implicit

foundation for

sustainability decision-

making.

Sustainability effect

probabilities are

difficult to quantify.

The structure of

sustainability actions

and their environmental

effect are difficult to

formulate and perceive

holistically.

Severely restricted

ability to identify and

perceive sustainability

actions and their

environmental effect.

Complete uncertainty

about the sustainability

actions and

environmental effects

of actions.

(Hypothetical)

Implications to

sustainability analysis

Sustainability

analysis is not

needed.

Sustainability parameters

(likelihood and impact)

of environmental effect

can be measured and

assessed with certainty.

Sustainability

parameters (likelihood

and impact) of

environmental effect

cannot be objectively

assessed.

Sustainability actions

and their causalities

cannot be objectively

assessed.

Sustainability actions,

their causalities and

environmental effects of

actions are not fully

known and assessable.

Sustainability actions,

environmental effects

of actions and related

parameters cannot be

assessed.

ICORES 2022 - 11th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

246

The rows in this framework describe the decision-

makers knowledge, understanding of surroundings

and causalities of taken actions, implications of made

decisions, and lastly the analytical capabilities based

on the possessed knowledge. For studying real

companies, the focus should be directed to the middle

states of certainty. This allows the assessment of

companies’ capabilities to conduct informed

sustainability related decision-making and self-

evaluation of sustainability performance.

When a company’s management has procedural

uncertainty, they lack required knowledge to conduct

informed decision-making. In this situation, the

consequences of company’s actions are not

considered, leaving that company prone to unwanted

outcomes realized from otherwise benevolent

decisions (Dosi and Egidi, 1991). This is due to the

incapability to recognize sustainability related issues,

counteractions, their benefits, and disadvantages.

Furthermore, since the knowledge is inadequate, the

decisions cannot be backed by data, i.e., necessary

measurements and analysis is impossible to carry out.

Under structural uncertainty, the management

has an idea about the parameters of sustainability

related decision-making, e.g., what kind of

technologies can be implemented in operations to

reduce environmental impact. However, choosing the

appropriate actions is hindered by the lack of

knowledge on all available courses of action. When

the appropriate courses of actions are clear to

management, the degree of certainty is parametric

uncertainty. Here the management can perceive

different appropriate decision paths but

understanding of their impacts and related

probabilities are unknown (Langlois, 1984). In other

words, the different pathways for the company are

visible, but capability to choose the best one is

limited.

Parametric certainty is the next step. When

management can reach this degree of certainty, their

decision-making is informed, backed up by data. Here

the circumstances, available actions, probabilities,

and possible outcomes are known by the decision-

makers.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

All the studied companies have dedicated some focus

to environmental issues in their operations. Mostly

the shift towards environmental awareness has been

happening lately, within past few years. Spark for the

change is due both governmental and societal

demand. In other words, regional and national

legislation has become stricter in terms of

environmental performance of companies. At the

same time, customers, consumers, and society at large

have become more vocal in their demands for

corporate sustainability in Finland. Since

environmental focus is a new direction for

companies, especially those in logistics sector, which

is known for characteristics such as traditional and

rigid, vast advances in environmental friendliness

cannot possibly be expected yet. Indeed, most of the

environmental advances in the studied companies

have been incremental. As such, the related

performance measurements are at basic level and lack

coordination with strategic goals (procedural

uncertainty). Therefore, management is not supplied

with proper data to support their decision making.

While the direction is correct for improved

environmental performance, strategic

implementation of environmental practices and

technologies is needed to create meaningful results

and simultaneous benefits in terms of environmental

sustainability, societal approval, and economic profit.

When the strategic objectives for companies are

recognized, only then it is possible to measure correct

things in operations (i.e., ascension to structural

uncertainty and beyond). Furthermore, this also

enables management of sustainability and appropriate

control mechanisms.

Some of the studied logistics companies possess

naturally advantageous position in environmental

sustainability (e.g., railway operators have access to

environmentally sound transportation when

compared to road transportation companies).

However, some of the mentioned companies are not

actively reinforcing their position regarding

environmental sustainability. In other words, some

logistics companies do not recognize competitive

advantages in environmental sustainability, and

furthermore take for granted the most likely

temporary advantageous position. The position can be

described as temporary since some of the other

studied companies (without inherent advantage in

environmental sustainability, e.g., road

transportation) are actively strategically thriving a

position of forerunner regarding environmental issues

in logistics industry.

While it is reasonable to assume that some of the

distortion in environmental self-evaluation and actual

performance is due to the lacking capabilities in

environmental sustainability or “meta-ignorance”,

possible impact of external influence should also be

entertained. For example, in Finland, utilizing

biodiesel in road transportation is subject of high-

profile marketing and is also recommended by

Is Ignorance a Bliss in Sustainability? Evaluating the Perceptions of Logistics Companies’ Self-Assessment in Environmental Performance

247

government through various programs and legislation

(e.g., Finnish Tax Administration, 2020). However, it

is debatable how beneficial for overall environmental

sustainability of transportation these biofuels are.

Nevertheless, many of the studied companies have

been introducing biofuels, especially biodiesel, to

their operations. Based on the interviews, it seems

that these same companies lull in a feeling of

achieved environmental sustainability after changing

to biodiesel. At the same time, the environmental

impact of these companies’ operations is lowered

only marginally if at all.

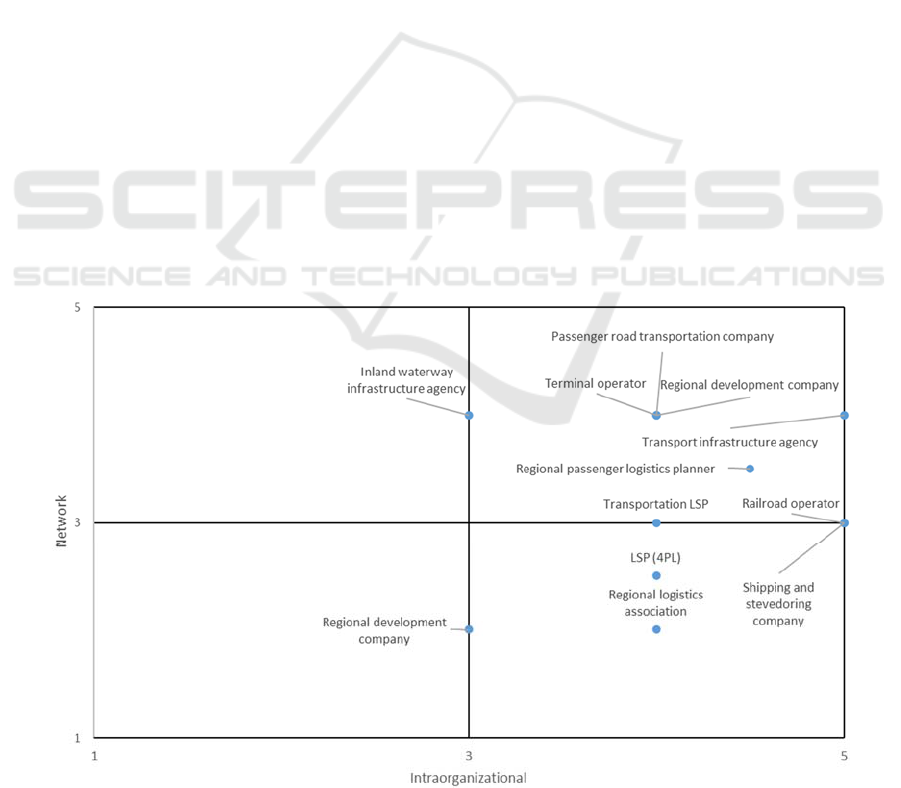

The self-evaluation grades (1-5) of value for

environmental sustainability in companies’ operation

and that in their network is presented in Figure 1.

When considering both company’s and their

network’s score, it is possible to divide the

interviewee companies to four different categories.

Top left (high importance of environmental

sustainability in network, low inside organization) is

for reactionary companies who act upon changes in

their direct business surroundings and are not prone

to proactive decisions. Bottom left (low network and

organizational importance) is for companies acting in

networks that have not recognized value in

environmental sustainability. Bottom right (low

network, high organizational importance) is for

companies positioned as forerunners in

environmental sustainability: their network is not

pushing for environmental performance, but they

proactively act towards that. Lastly, top right (high

network and organizational importance) contains

companies operating in networks which recognize

value in environmental sustainability.

Majority of studied companies are positioned to

top right, to environmental focused companies among

others, according to their self-evaluation. Second

largest group can be categorized as environmental

forerunners according to their assessment, locating in

the bottom right. While none of the companies

position themselves on the categories represented on

left side of the matrix, two are on the edge. Inland

waterway infrastructure agency sees themselves as

moderately focused to environmental sustainability,

while admitting that their network values that highly.

Similarly, Logistics development company evaluates

themselves as moderate on environmental issues but

assesses surrounding network as not particularly

focused on environment. According to some of the

companies, environmental measurements and related

communications lack standardization. These

interviewees claim that it is extremely difficult to

benchmark environmental sustainability of logistics

operations between the companies. Lack of industry

standards in environmental measurements and

reporting is one factor explaining the relatively high

grading in self-evaluation for the studied companies.

It seems that none of the companies except one rated

their network’s focus on environment higher than

their own: a sign of the studied companies

overestimating their own alignment towards

environmental issues.

Figure 1: Evaluation for o

rganizational and network position

environmental sustainability.

ICORES 2022 - 11th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

248

5 DISCUSSION

This research continues from the previous scientific

discussion (Vilko et al., 2014; Dunning, 2011) by

synthesizing on uncertainty and biases in decision-

making in sustainability context. Informed decision-

making in supply chains under uncertainty requires

adequate cognitive abilities (Vilko et al., 2014).

Similarly, decisions towards environmental

sustainability in supply chains require specific

knowledge to understand causalities, impacts, and

outcomes of those decisions (Kelle et al., 2019).

The multiple case study on intermodal logistics

system reveals that most of the studied companies

have taken some substantial steps towards improving

their environmental sustainability. In most cases, this

can be boiled down to implementing some

incremental advancements on top of the existing

operations, e.g., using biodiesels in road

transportation instead of conventional fuels.

However, at the same time the pursuit for

environmental sustainability seems to be limited to

these incremental changes – companies are hesitant to

make strategic and structural changes to existing

operations to improve their environmental

performance.

While most of the companies describe their

actions towards environmental sustainability as

conservative, most still evaluate their own

environmental sustainability and that of their

immediate networks highly. This represents an

obvious mismatch in actions and communications

related to environmental sustainability. The situation

can also be interpreted as companies having illusory

superiority. First initial decisions towards reducing

environmental burden of operations are made, tying

investments, time, and work to environmental

challenges. This in turn could create a feeling of

radical improvement, especially since rigid

benchmarking in environmental context between

companies is lacking. Therefore, it is relatively for

companies to evaluate their environmental focus as

exceptionally high. Organizations with longer

experience in environmental advances, however, hold

more informed view on environmental decision-

making and desired outcomes. For example, the

studied fourth-party logistics service provider, which

has carried out numerous environmental programs for

its customers (logistics companies), can be seen

possessing a more informed view on the matter.

While they rank themselves high in environmental

sustainability, they see their network performing

below average on the matter. Similarly, the studied

logistics development company, which intends to

create modern, competitive regional logistics, sees

the surrounding logistics industry as immature when

it comes to environmental sustainability.

However, it is not fair assessment to attribute the

high grades solely on illusory superiority. For

example, the studied transportation LSP company has

been positioning themselves as a forerunner in

environmental issues for decades already. In their

case, environmental sustainability has been lifted as

part of their strategy and they believe that this

direction will grant them prolonged competitive

advantages. Business processes have been coupled

with measurements, and appropriate data on

sustainability goals reaches the management. In other

terms, they can be seen as reaching for parametric

certainty in sustainability related decision-making.

Therefore, they rightfully grade themselves high in

environmental sustainability while at the same time

assessing their network as low on the matter.

Interestingly, the studied railroad operator

assesses themselves exceptionally high, with full

score. Indeed, railway transportation in Finland,

where most of the tracks are electrified and

hydroelectricity is preferred power source, can be

considered as environmental alternative for

transportation. However, during the interview with

this company, it was evident that they are not

strategically pursuing to improve their position

regarding environmental sustainability in logistics

industry. In other words, they seem to feel secure in

their current position, and are not actively trying to

improve environmental sustainability of their

operations. In future, this could lead to other actors in

the industry in taking over parts of the market which

values environmental sustainability. In worst case

scenario, inaction now could lead to lost market

position in the future, stemming partly from illusory

superiority. Especially as some of the other studied

companies are more aggressively redefining their

businesses to become more environmentally sound.

6 CONCLUSIONS

So, is (unintentional) ignorance a bliss in the context

of environmental sustainability in the studied

industry? In short term, it is easier to implement

sustainability superficially to company’s strategy

with ambiguous measurements and reporting.

However, if improvements in this regard are not

made, it can be costly for the company in future.

Long-term planning is not an easy road to travel: the

more is known, the more the required work for

meaningful sustainability actions becomes apparent.

Is Ignorance a Bliss in Sustainability? Evaluating the Perceptions of Logistics Companies’ Self-Assessment in Environmental Performance

249

There are also scientific implications for this

research. It seems that psychological phenomena,

such as illusory superiority, are not extensively

considered in organizational studies. According to the

authors best knowledge, only a few studies consider

such bias in research which relies on informant

companies’ self-evaluation. In addition, as corporate

sustainability is still emerging topic in academia as

well as in practice, biases in self-assessment manifest

easily due to the lack in long-term experience. The

proposed framework helps in structuring

sustainability related decision-making and

understanding causalities and possible outcomes. It

offers a way to evaluate the current situation of a

company, as well as what is needed to improve in

informed environmental decision-making.

This study offers several managerial implications.

Firstly, the multiple case study of a multimodal

logistics system presents a snapshot on how

environmental sustainability is regarded in such

business environment. Secondly, the empirical study

shows that all the companies in the given industry are

shifting their focus to environmental challenges.

Some do so more actively than others, but the overall

notion is that there is growing value in environmental

sustainability in logistics. Lastly, the used certainty

framework illuminates some pitfalls in environmental

decision-making, and that false sense of superiority

could be detrimental to a company’s long term overall

performance. As a major takeaway, companies

should thrive to carry out meaningful measurements

to enable informed decision-making based on data

and knowledge.

Limitations of this research make it difficult to

justify the experienced effect in sustainability related

self-assessment as wide scale phenomenon. This

multiple case study focuses on a single industry in a

specific geographical location. However, further

studies can be extended to multiple industries in a

wider geographical scale. In addition, further research

should aim to gather quantitative data on the

phenomenon to investigate how wide the self-

assessment bias is in companies.

REFERENCES

Ahiaga-Dagbui, D. D., & Simon, D. S. (2014). Rethinking

Construction Cost Overruns: Cognition, Learning and

Estimation. Journal of Financial Management of

Property and Construction, 19(1), 38–54.

Dosi, G., & Egidi, M. (1991). Substantive and procedural

uncertainty: An exploration of economic behaviours in

changing environments. Journal of evolutionary

economics, 1(2), 145-168.

Dunning, D. (2011). The Dunning-Kruger effect. On being

ignorant of one’s own ignorance. In Advances in

Experimental Social Psychology (1st ed., Vol. 44).

Elsevier Inc.

European Commission (2021). A European Strategy for

low-emission mobility. Available at:

https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/transport_en

Accessed 6 Nov 2021.

Feld, J., Sauermann, J., & de Grip, A. (2017). Estimating

the relationship between skill and overconfidence.

Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics,

68, 18–24.

Finnish Government. (2020). Transport emissions halved

by 2030 – requires an extensive range of options.

Available online: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/-/liikenteen-

paastot-puoleen-2030-mennessa-tarvitaan-laaja-

keinovalikoima?languageId=en_US Accessed 6 Nov

2021.

Finnish Tax Administration. (2020). Biopolttoaineiden

jakeluvelvoite. Translation by the authors: Biofuel

distribution obligation. Available online:

https://www.vero.fi/syventavat-vero-ohjeet/ohje-

hakusivu/56210/biopolttoaineiden-jakeluvelvoite2/

Accessed 3 Nov 2021.

Ge, L., & Brewster, C. A. (2016). Informational institutions

in the agrifood sector: Meta-information and meta-

governance of environmental sustainability. Current

Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 18, 73–81.

Haas, T., & Sander, H. (2020). Decarbonizing transport in

the European Union: Emission performance standards

and the perspectives for a European green deal.

Sustainability, 12(20).

Langlois, R.N. (1984). Internal organization in a dynamic

context: some theoretical considerations. In Jussawalla,

M. and Ebenfield, H. (eds), Communication and

information economics: new perspectives, North

Holland, Amsterdam.

Loasby, B.J. (1976). Choice, complexity and ignorance: an

enquiry into economic theory and practice of decision

making. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Kelle, P., Song, J., Jin, M., Schneider, H., & Claypool, C.

(2019). Evaluation of operational and environmental

sustainability tradeoffs in multimodal freight

transportation planning. International Journal of

Production Economics, 209, 411–420.

Seuring, S., & Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review

to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain

management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15),

1699–1710.

Solaymani, S. (2019). CO

2

emissions patterns in 7 top

carbon emitter economies: The case of transport sector.

Energy, 168, 989–1001.

Vilko, J., Ritala, P., & Edelmann, J. (2014). On uncertainty

in supply chain risk management. International Journal

of Logistics Management, 25(1), 3–19.

ICORES 2022 - 11th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

250