A Study on Teachers’ Design Choices Regarding

Online Collaborative Learning

Francesca Pozzi

a

, Flavio Manganello

b

and Donatella Persico

c

Istituto Tecnologie Didattiche, CNR, Via De Marini, 16, Genoa, Italy

Keywords: Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL), Italian Schools, Teaching Practice, Learning Design,

Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT).

Abstract: This study aims to contribute to our understanding of whether and to what extent collaboration is a

consolidated teaching practice in Italian schools. The paper reports the results of a survey of Italian teachers

(N=268) that investigated (self-reported) behaviours regarding the design of collaborative learning activities

(prior to and during the pandemic). Results show that even if collaborative learning approaches are

implemented to some extent by Italian teachers and were also proposed online as part of Emergency Remote

Teaching during the lockdown - their design choices are not always in line with recommendations widely

agreed by the Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) research community.

1 INTRODUCTION

For a couple of decades, research in the Technology

Enhanced Learning (TEL) field has been advocating

a shift in pedagogical perspectives in school, from

transmissive approaches, to learner centred and

collaborative approaches, based on socio-

constructivist learning theories. This shift has

happened to some extent, even if it seems

collaborative teaching and learning are not yet

commonplace in schools across Europe and “teaching

about or through collaboration remains uncommon in

schools.” (Cassells, 2018).

Moreover, it is not completely clear whether and to

what extent technologies are fully exploited to support

collaborative learning in school (Beldarrain, 2007) and

this is usually blamed on the fact that, on average, less

than 40% of teachers across the EU feel ready to use

digital technologies in teaching (OECD, 2018).

Such limited capacity has been put under the lens

especially during the recent lockdown imposed by

many governments due to the covid-19 pandemic,

which forced about 1.5 million learners to move to

emergency remote teaching (UNESCO, 2020). On that

occasion, the TEL research community leapt into

action to analyse such a huge, unprecedented set of

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3592-2131

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7584-939X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4574-0427

experiments-in-the-wild taking place in schools, which

afforded researchers a unique opportunity to examine

how institutions, students and teachers were coping

with that situation. The preliminary results seem to

indicate in most cases online teaching took the form of

a simple ‘replication’ in online environments of

traditional teaching approaches, often transmissive in

nature and most of the times synchronous (Collazos et

al., 2021). This is in contrast with many years of

research in the field of Computer Supported

Collaborative Learning (CSCL) that proved the need to

design online collaborative learning bearing in mind

not only the different affordances of the technological

tools, but also the importance of artefacts as catalysts

of knowledge building (Stahl et al., 2021; Paavola &

Hakkarainen, 2009) and the essential role of

collaborative techniques in scaffolding collaboration

(Pozzi & Persico, 2011). The effects of “collaborative

techniques”, such as Jigsaw, Case study, Brain

storming, Peer review, Role play, Pyramid, on

learners’ collaboration have been investigated by

researchers in learning design and the outcomes of

such research should inform the decision making

process involved in designing for learning (Laurillard,

2012; Persico, Pozzi, Goodyear, 2018; Pozzi, 2010;

Pozzi, 2011; Pozzi et al., 2016). In an attempt to

Pozzi, F., Manganello, F. and Persico, D.

A Study on Teachers’ Design Choices Regarding Online Collaborative Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0010952100003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 2, pages 599-605

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

599

understand what the current attitudes and behaviours of

school teachers are in respect to the design and

application of collaborative learning and the related

research evidence, and to understand how the use of

technology intertwines with it, we have conducted a

study targeting Italian school teachers. Particularly, we

have analysed the self-reported behaviours of Italian

teachers as far as the adoption of collaborative learning

approaches prior to and during the pandemic. The

research questions were:

RQ1. What are the approaches used by Italian

teachers to design collaborative activities? Is there

any difference between their design approaches

before and during the emergency (i.e., in face-to-face

and online settings)?

RQ2. What is the nature of the proposed

collaborative patterns/ activities? Is there any

difference between the nature of collaborative

activities before and during the emergency?

RQ3. What technologies are used in the

proposed collaborative activities? Is there any

difference between the technologies used before and

during the emergency?

2 METHODOLOGY

The study was based on a bespoke survey that was

devised by the authors to investigate relevant aspects

of the design of collaborative learning activities.

Participants were recruited by using a convenience

sampling method. The survey, implemented with the

Google Form functionality, was addressed to school

teachers and comprised a total of 27 questions, aimed

at collecting data concerning respondents’ self-

reported design behaviours for face-to-face and

online teaching. The questionnaire also contained a

consent form regarding the management of personal

data, according to the GDPR.

In terms of data analysis, we conducted a

descriptive and inferential statistical analysis using

SPSS (version 22.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Means and standard deviations were calculated to

describe continuous variables. The categorical

variables were presented as absolute (n) and relative

(%) frequencies. To test the associations among

categorical variables, we used the Chi-Square test of

independence.

2.1 Context of the Study and

Participants

The questionnaire was advertised in the context of a

number of online training activities organized by

ITD-CNR in Spring 2020, as a response to the urgent

need expressed by the Italian schools to receive

specific training for teachers on how to tackle the shift

from face-to-face to online teaching. It was presented

at the end of the training and trainees were invited to

voluntarily fill it in soon after the training.

Overall, we collected 268 responses. Participants

were 196 females (73,13%) and 66 males (24,63%)

(with 6 undisclosed). The unbalance reflects a similar

unbalance in the target teacher population in Italy

(OECD, 2021).

Regarding the school level of respondents, our

sample was composed as follows: Kindergarten = 12

(4,48%), Primary school = 60 (22,39%), Lower

Secondary school = 48 (17,91%), Upper secondary

school = 145 (54,1%), Other (not specified) = 3

(1,12%).

In terms of teaching experience, our respondents

had on average 19,56 years of teaching experience

(SD = 9,40; Min = 1, Max = 40), which is in line with

the trend at national level (OECD, 2021).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Approaches Used to Design

Collaborative Activities (RQ1)

Regarding the design of collaborative activities, first

of all, we asked teachers how long they usually

dedicate to this task. This was used also to detect how

many of them did not dedicate any time to this task.

Most of the participants reported that they usually

dedicate a few hours (52.6%) or some days (25%) to

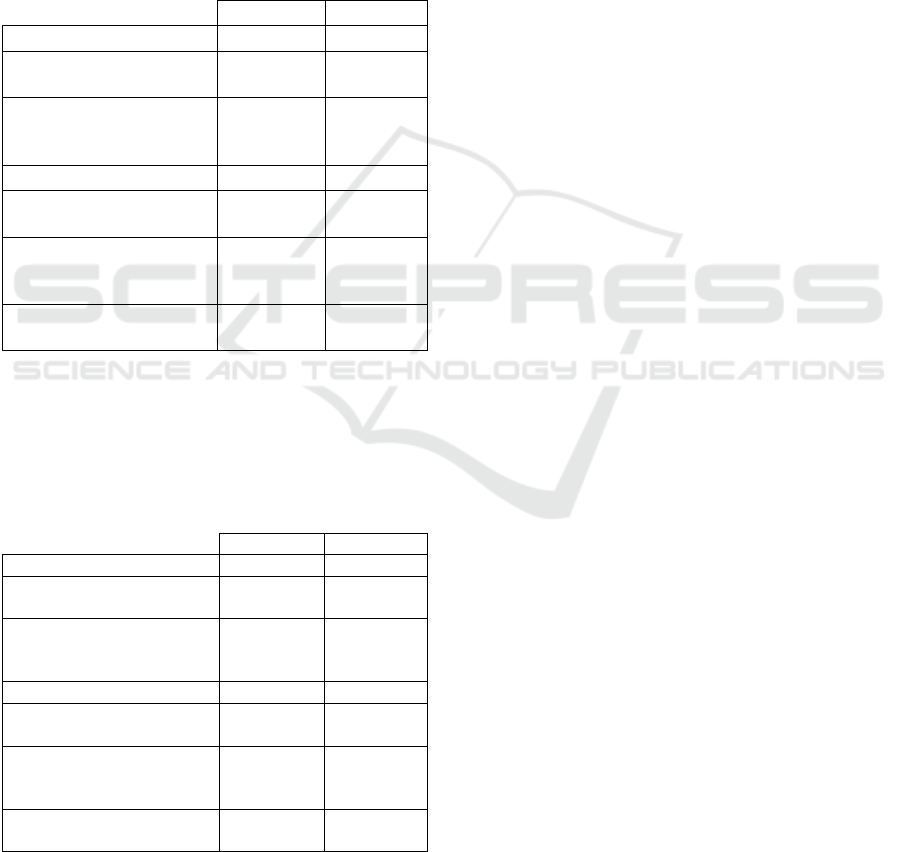

this task. Table 1 shows the complete picture of their

responses.

Table 1: Time dedicated to the design of collaborative

activities (frequency and percentage).

Frequenc

y

Percentage

Some minutes 19 7.1

Some hours 141 52.6

Some da

y

s 67 25.0

Some weeks 15 5.6

Usually not designing

collaborative activities

26 9.7

Total 268 100.0

It is worth noting that a small percentage (26

participants, 9.7%) reported that they do not usually

design collaborative activities at all. More precisely,

17 teachers declared they do not design, nor deliver

any collaborative activity, while 9 teachers do deliver,

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

600

without any design phase. So, from now on, the data

will include only responses from teachers who

usually design (n.=242).

Then, we asked what element they regard as most

relevant during the design, and we posed the question

by differentiating their behaviour between before

(i.e., usually) and during the pandemic. Table 2 shows

the results regarding the element considered most

relevant in the design of collaborative activities in

teachers’ usual design practice, before and during the

COVID-19 emergency. The choice of the elements is

based on the 4Ts model (Pozzi, Ceregini, Persico,

2016) that posits the importance and reciprocal

influence of task (i.e., tasks to be performed), time

(i.e., time schedule of the activity), team (i.e., teams

of students to be involved), and technology (i.e.,

technology to be used) in the design of online

collaborative learning.

Table 2: Element usually considered most relevant (before

and during the COVID-19 emergency) (frequency and

percentage).

Before the

COVID-19

emer

g

enc

y

During the

COVID-19

emer

g

enc

y

Frequ

enc

y

Percen

ta

g

e

Frequ

enc

y

Percen

ta

g

e

Tas

k

130 53.7 83 34.3

Time 36 14.9 32 13.2

Team 47 19.4 28 11.6

Technolog

y

22 9.1 65 26.9

Not responding 7 2.9 34 14.0

The data show that, with the pandemic, the

leading role of the Task in the pre-pandemic design

of collaborative learning activities has given way to

that of technology in pandemic practice.

A marginal homogeneity test determined that

there is a statistically significant difference in the

frequencies of responses before and during the

COVID-19 emergency, p < .001 (2 sided).

3.2 Nature of Collaborative Activities

(RQ2)

Table 3 shows the results regarding the use of seven

quite well known (Pozzi, Ceregini & Persico, 2016)

collaborative techniques (Discussion, Case Study,

Jigsaw, Brainstorming, Peer Review, Pyramid, Role

Play) in three different conditions:

A. Before the COVID-19 emergency (face to face

only).

B. Before the COVID-19 emergency (face to face

+ online).

C. During the COVID-19 emergency (online only).

Table 3: Nature of the proposed collaborative activities

(frequency and percentage).

Frequenc

y

Percentage

Discussion

A. Before (f2f only) 199 74.3

B. Before (f2f + online) 74 27.6

C. During (online only) 134 50.0

Case

Study

A. Before (f2f only) 82 30.6

B. Before (f2f + online) 48 17.9

C. During (online only) 62 23.1

Jigsaw

A. Before (f2f only) 32 11.9

B. Before (f2f + online) 18 6.7

C. During (online only) 24 9.0

Brain-

storming

A. Before (f2f only) 150 56.0

B. Before (f2f + online) 57 21.3

C. During (online only) 95 35.4

Peer

review

A. Before (f2f only) 71 26.5

B. Before (f2f + online) 34 12.7

C. During (online only) 48 17.9

Pyramid

A. Before (f2f only) 11 4.1

B. Before (f2f + online) 10 3.7

C. During (online only) 14 5.2

Role Play

A. Before (f2f only) 80 29.9

B. Before (f2f + online) 27 10.1.

C. During (online only) 37 13.8

Discussion. Cochran’s Q test indicated that there were

differences between the three conditions, x2(2, N = 268)

= 130.28, p < .001. A pairwise post-hoc Dunn test with

Bonferroni adjustments was significant for AB (p < .001),

BC (p < .001), and AC (p < .001).

Case Study. Cochran’s Q test indicated that there were

differences between the three conditions, x2(2, N = 268) =

20.14, p < .001. A pairwise post-hoc Dunn test with

Bonferroni adjustments was significant for AB (p < .001)

and AC (p = .026).

Jigsaw. Cochran’s Q test indicated that there were

differences between the three conditions, x2(2, N = 268) =

6.30, p = .043. A pairwise post-hoc Dunn test with

Bonferroni adjustments was significant for AB (p = .037).

Brainstorming. Cochran’s Q test indicated that there

were differences between the three conditions, x2(2, N =

268) = 97.17, p < .001. A pairwise post-hoc Dunn test with

Bonferroni adjustments was significant for AB (p < .001),

BC (p < .001), and AC (p < .001).

Peer Review. Cochran’s Q test indicated that there were

differences between the three conditions, x2(2, N = 268) =

24.07, p < .001. A pairwise post-hoc Dunn test with

Bonferroni adjustments was significant for AB (p < .001)

and AC (p = .008).

Role Play. Cochran’s Q test indicated that there were

differences between the three conditions, x2(2, N = 268) =

19.86, p < .001. A pairwise post-hoc Dunn test with

Bonferroni adjustments was significant for AB (p < .001)

and AC (p < .001).

A Study on Teachers’ Design Choices Regarding Online Collaborative Learning

601

3.3 Technologies (RQ3)

Table 4 shows the results regarding the Technologies

typically used in the proposed collaborative activities,

in face-to-face or blended education contexts (before

the pandemic). Again, in this case, only 242 of the

total 268 participants are considered, excluding the 26

who previously stated that they do not usually design

collaborative activities. Each participant could

indicate more than one option.

Table 4: Technologies used in collaborative activities

before the COVID-19 Emergency (frequency and

percentage).

Frequency Percentage

Forum 30 12.4

Web conferencing (e.g.,

Meet, Zoom, Skype)

13 5.4

Social network (e.g.,

WhatsApp, Facebook,

Instagram)

45 18.6

Interactive Whiteboard 151 62.4

Text editor (e.g., MS

Word, Google docs, Wiki)

121 50.0

Presentation (e.g., MS

PowerPoint, Google

Presentation, Prezi)

151 62.4

Instructional software,

digital games, simulations

75 31.0

Table 5 shows the results regarding the

technologies used to support the proposed

collaborative activities, during the COVID-19

emergency.

Table 5: Technologies used during the COVID-19

emergency (frequency and percentage).

Fre

q

uenc

y

Percenta

g

e

Forum 28 11.6

Web conferencing (e.g.,

Meet, Zoom, Skype)

189 78.1

Social network (e.g.,

WhatsApp, Facebook,

Insta

g

ram

)

74 30.6

Interactive Whiteboar

d

11 4.5

Text editor (e.g., MS

Word, Google docs, Wiki)

110 45.5

Presentation (e.g., MS

PowerPoint, Google

Presentation, Prezi

)

144 59.5

Instructional software,

digital games, simulations

66 27.3

A McNemar's test determined that there was a

statistically significant difference in the frequency

before and during the COVID-19 emergency for Web

conferencing tools (p < .001), social network tools (p

< .001), and for interactive whiteboard (p < .001).

4 DISCUSSION

In the following we discuss the results, basing on the

3 research questions.

4.1 Approaches Used to Design

Collaborative Activities (RQ1)

Regarding the design of collaborative activities, a

preliminary question intended to check to what extent

respondents dedicate time to the design of

collaborative activities. Only a minority of them

(9,7%) do not dedicate any time to their design, while

the majority (52,6%) state they usually take some

hours or even days (25,0%) to this task.

Interestingly, among those who do not design, 9

teachers (3,3%) deliver collaborative activities

without designing them, which is definitely in

contrast with the recommendations provided by the

CSCL research community stating that collaboration

does not happen automatically, and teachers need to

design and create the conditions to foster effective

group interactions (Law et al, 2021).

Regarding the element of design that is considered

most relevant, it seems in face-to-face settings the

design process was primarily Task-oriented, while

during the emergency, it became more Technology-

driven.

This is not surprising, as during the lockdown

teachers were forced to use technological tools (to

mediate communication with students, to assign

tasks, to collect assignments, etc.) which in the

previous, non-pandemic scenario were available, but

not mandatory. It is worthwhile mentioning that,

although in the past the Italian government invested

quite a lot in terms of ICT equipment for all the

schools through a number of national programmes,

the use of technologies by teachers is still limited.

This is clearly stated by a recent OECD report: “…in

Italy teachers use technology well below other high-

skilled workers. Additionally, 3 out of 4 teachers

report needing further training in ICT for teaching.”

(OECD, 2019).

It will be interesting to re-check the data about use

of (and familiarity with) technologies by Italian

teachers in the future, to see if any change has

occurred in their use of technology as a consequence

of this long period.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

602

4.2 Nature of Collaborative Activities

(RQ2)

As far as the nature of the collaborative activities

proposed, we have investigated the use of a number

of collaborative techniques/patterns (face-to-face or

blended) and online (during the pandemic). In

general, it appears that the number of respondents

who uses these techniques in face-to-face mode is

significantly higher than those who used it online (for

all techniques except the Jigsaw). This is true

especially for the Role Play, where the gap between

frequencies is the highest. In turn, the number of

teachers that use them in online mode, is higher than

those who use them in blended mode. Among the

techniques, Discussion and Brainstorming are the

most commonly used patterns/techniques. Pyramid

and Jigsaw are far less used. Case Study, Peer Review

and Role Play are moderately common techniques,

especially in face-to-face conditions.

This seems to confirm what we have already

pointed out under RQ1, i.e., it seems some teachers

tend to perceive the online environment as a barrier,

rather than an advantage, to the implementation of

collaborative learning approaches, in contrast to what

is claimed by the CSCL research community

(Garrison et al., 1999; Stahl et al., 2021).

Moreover, the added value of more structured

techniques, such as for example the Pyramid or the

Jigsaw, where the social structure (i.e., the team

composition) evolves during the activity, seems to be

still overlooked, in favour of ‘flatter’ techniques.

Although the debate about the effects of different

degrees of structuredness of collaborative techniques

is still ongoing in the CSCL community (Dillenbourg,

2002; Law et al., 2021; Persico & Pozzi, 2011;

Radkowitsch et al., 2020), there are evidences of

benefits brought about by structured techniques and

scripts (Weinberger et al., 2005; Pozzi, 2010; Pozzi et

al., 2016), so – again in this case - it seems teachers’

design choices do not fully resonate with research

results.

4.3 Technologies (RQ3)

Regarding the technological tools used during

collaborative learning activities, obviously we

observe a drastic increase in the use of synchronous

online communication tools during the lockdown

(especially video-conferencing systems, that moved

from 5.4% to 78.1%, but also social networking tools,

from 18.6% to 30.6%), along with a decrease of the

use of the interactive whiteboards. These results are

easy to explain: while video-conferencing systems

were hardly used before the lockdown, as classes

worked mainly (if not exclusively) face-to-face, the

emergency teaching was almost exclusively based on

these tools. At the same time, interactive whiteboards

were mainly used in face-to-face classes, but became

inaccessible during the lockdown. Social networking

tools, already used to some extent by teachers before

the pandemic, became more important as a

communication channel between teachers and

students.

What is more interesting to note, is that the use of

forums is not significantly affected by the emergency

teaching. This suggests the advantages of

asynchronous communication to mediate online

collaborative activities, that are so often claimed in

the scientific literature (Garrison et al., 1999; Means

et al., 2009; Greenhow et al., 2020; Persico & Manca,

2000), is disregarded by teachers. The permanent

nature of asynchronous interactions allows for more

reflection and critical thinking, permits students to

proceed at their own pace and - last but not least – can

mitigate digital inequalities (Williamson et al., 2020,

Giovannella, Passarelli & Persico, 2020), in that it

limits connection issues and other socio-cultural

barriers that frequently hinder synchronous events.

But it seems these useful features tend to be

overlooked by teachers.

Last but not least, consideration should be given

to lower use, during the remote teaching, of software

to produce artefacts, such as for example text editors

or presentation software. Even if not statistically

significant, the difference is somehow surprising,

because it might imply online group-work – when

proposed – was not always oriented to the production

of an artefact, an aspect that is highly recommended

by the CSCL community (Paavola & Hakkarainen,

2009; Stahl et al., 2014).

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper reports the results of a study based on the

collection of self-reported data concerning Italian

teachers’ behaviours towards collaborative learning

approaches. Since our study was based on a

convenience sampling method as well as on self-

reported data, our findings are not generalizable;

nonetheless, they can provide insights and trigger the

discussion about teachers’ competences on learning

design.

Overall, the results indicate collaborative learning

approaches are to some extent adopted and applied,

but it seems some of the design choices made by the

A Study on Teachers’ Design Choices Regarding Online Collaborative Learning

603

teachers are not in line with what is recommended by

the CSCL research community.

These results seem to highlight there is a need for

teacher training in the field of online collaborative

learning approaches. This is quite in line with Tallent-

Runnels et al. (2006) who state teacher training and

support are crucial to the design and implementation

of quality online environments. Our study has

highlighted there seem to be aspects related to how to

effectively design online collaborative activities that

– although well acknowledged by the research

community - cannot be taken for granted for

practitioners. These aspects include, but are not

limited to, the importance of using structured

techniques, asynchronous communication and the

essential role of artefacts as catalysers of

collaboration.

Further research directions should include data

collection with a larger, international sample, to

compare the results with data concerning other

countries.

Another aspect that deserves further investigation,

is the extent to which the different approaches

adopted in face-to-face or online settings will remain

once the teachers will be free again to choose between

the two delivery modes and to carefully design their

teaching, by choosing technology mediated teaching

when it has a pedagogical added value, and face-to-

face or blended settings, when their advantages

overcome the disadvantages.

REFERENCES

Cassels, D. (2018). Integrating Collaborative Learning in

Policy and Practice. CO-LAB’s Conclusions and

Recommendations. European Schoolnet. Retrieved at:

http://colab.eun.org/c/document_library/get_file?uuid

=387a2113-e87e-4f2f-bd90-

b3b1b7d9404a&groupId=5897016

Beldarrain, Y. (2007). Distance Education Trends:

Integrating new technologies to foster student

interaction and collaboration. Distance education,

27(2), 139-153

Collazos, C., Pozzi, F., & Romagnoli, M. (2021). The use

of e-learning platforms in a lockdown scenario – A

study in Latin American. IEEE Revista Iberoamericana

de Tecnologias del Aprendizaje.

Dillenbourg, P. (2002). Over-scripting CSCL: The risks of

blending collaborative learning with instructional

design. In: P. A. Kirschner (Ed.) Three worlds of CSCL.

Can we support CSCL?, Heerlen, Open Universiteit

Nederland, pp.61-91

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999).

Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer

conferencing in higher education. The Internet and

Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Giovannella, C., Passarelli, M., & Persico, D. (2020). The

Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Italian Learning

Ecosystems: the School Teachers’ Perspective at the

steady state. ID&A Interaction Design &

Architecture(s), 45, 264-286.

Greenhow, C., Lewin, C., & Staudt Willet, K. B. (2020).

The educational response to Covid-19 across two

countries: a critical examination of initial digital

pedagogy adoption. Technology, Pedagogy and

Education, 1-19.

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a design science:

Building pedagogical patterns for learning and

technology. Routledge.

Law, N., Järvelä, S. & Rosé, C. Exploring multilayered

collaboration designs. International Journal of

Computer Supported Collaborative Learning, 16, 1–5

(2021).

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones,

K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in

online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online

learning studies. Retrieved at: https://eric.ed.gov/?

id=ED505824

OECD (2018) TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I) - Teachers

and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. Retrieved at:

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/talis-2018-

results-volume-i_1d0bc92a-en

OECD (2019). OECD Skills Outlook - Thriving in a Digital

World. Retrieved at: https://doi.org/10.1787/df80bc12-

en

OECD (2021). Education at a Glance 2021. Retrieved at:

https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/

Paavola, S., & Hakkarainen, K. (2009). From meaning

making to joint construction of knowledge practices

and artefacts–A trialogical approach to CSCL. In:

Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on

Computer Supported Collaborative Learning,

CSCL'09, Rhodes, Greece, June 8-13, 2009.

Persico, D., & Manca, S. (2000). Use of FirstClass as a

collaborative learning environment. Innovations in

Education and Training International, 37(1), 34-41.

Persico, D., & Pozzi, F. (2011). Task, Team and Time to

structure online collaboration in learning environments.

World Journal on Educational Technology, 3(1), 01-15.

Persico, D., Pozzi, F., & Goodyear, P. (2018). Teachers as

designers of TEL interventions. British journal of

educational technology, 49(6), 975-980.

Pozzi F. (2010). Using Jigsaw and Case study for

supporting collaboration online. Computers &

Education, 55, 67-75.

Pozzi, F. (2011). The impact of scripted roles on online

collaborative learning processes. International Journal

of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6(3),

471-484.

Pozzi F., Persico D. (Eds.). (2011). Techniques for

Fostering Collaboration in Online Learning

Communities. Theoretical and practical perspectives.

Hershey: IGI Global.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

604

Pozzi F., Ceregini A., Ferlino L., Persico D. (2016). Dyads

Versus Groups: Using Different Social Structures in

Peer Review to Enhance Online Collaborative Learning

Processes. The International Review of Research in

Open and Distributed Learning (IRRODL), 17(2), 85-

107.

Pozzi, F., Ceregini, A., Persico, D. (2016). Designing

networked learning with 4Ts. In: Cranmer S, Dohn NB,

de Laat M, Ryberg T & Sime JA. (Eds.), Proceedings

of the 10th International Conference on Networked

Learning 2016.

Radkowitsch, A., Vogel, F., & Fischer, F. (2020). Good for

learning, bad for motivation? A meta-analysis on the

effects of computer-supported collaboration scripts.

International Journal of Computer-Supported

Collaborative Learning, 15(1), 5-47.

Stahl, G., Ludvigsen, S., Law, N. et al. (2014). CSCL

artifacts. Intern. Journal of. Computer Supported

Collaborative Learning, 9, 237–245.

Stahl, G., Koschmann, T., & Suthers, D. (2021). Computer-

supported collaborative learning. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.),

Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences, Third

edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Tallent-Runnels, M. K., Thomas, J. A., Lan, W. Y., Cooper,

S., Ahern, T. C., Shaw, S. M., & Liu, X. (2006).

Teaching courses online: A review of the research.

Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 93-135.

UNESCO (2020). Education: From disruption to recovery.

Retrieved at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/education

response

Weinberger, A., Reiserer, M., Ertl, B., Fischer, F. & Mandl,

H. (2005). Facilitating collaborative knowledge

construction in computer-mediated learning

environments with cooperation scripts. In: R. Bromme,

F. W. Hesse & H. Spada, Barriers and biases in

computer-mediated knowledge communication, Berlin:

Springer 2005, p. 15 -37.

Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Potter, J. (2020). Pandemic

politics, pedagogies and practices: digital technologies

and distance education during the coronavirus

emergency. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2),

107-114.

A Study on Teachers’ Design Choices Regarding Online Collaborative Learning

605